Alfredo Duran

Alfredo Duran was born in Cuba in 1939. He left Havana after Fidel Castro gained power and joined the anti-Castro community in Florida.

Duran, a member of the Brigade 2506,took part in the Bay of Pigs. He later said: "We landed on the beach on the evening or the night of April 17, full of hope. We believed that we were going to win or die. We never believed that we were going to lose and live." Duran was captured and held prisoner until the American government agreed to pay the ransom.

Duran became a lawyer when he returned to the United States. He remained active in the anti-Castro movement and eventually became president of the Veteran's Association of Brigade 2506.

In the early 1990s Duran began to urge negotiations with Castro's government. In 1993 he was expelled from the Veteran's Association of Brigade 2506 for "reasons associated with his public statements indicating his willingness to go to Havana to discuss the history of the Bay of Pigs invasion.". As a result Duran established the Cuban Committee for Democracy (CCD).

In March, 2001, Duran was a member of a United States delegation that visited the scene of the Bay of Pigs battle. The party included Arthur Schlesinger (historian), Robert Reynolds, (the CIA station chief in Miami during the invasion), Jean Kennedy Smith (sister of John F. Kennedy), Wayne S. Smith (a U.S. diplomat stationed in Havana) and Richard Goodwin (Kennedy political adviser and speech writer). Duran later commented: "This has been a very emotional time, especially discussing with the colonel in charge of the operation the very intense fighting that took place in this spot."

Alfredo Duran is currently vice president and managing director of Miami’s WYHS, Channel 69, the first station to launch English-language locally-produced programming.

Primary Sources

(1) Alfredo Duran interviewed by PBS in 2001.

PBS: Are you still active in the Bay of Pigs Association?

Alfredo Duran: I was president of the Bay of Pigs Veterans Association for two years in a row, and I continued to be active in the association until approximately four or five years ago, when I was more or less thrown out of the association for being what the Cuban community calls a "dialogado," which is a person who wants to establish a dialogue with the Cuban government to bring about a transition towards democracy in Cuba. To the right wing or more conservative community here in Miami, a dialogado is the worst thing that you could be called. It implies that you're a traitor.

PBS: But you were pretty right wing. . . .

Alfredo Duran: I was pretty conservative, pretty right wing. You have to remember that, in the 1960s and 1970s, I, as most of the Cuban-Americans or Cubans who were here in Miami, was working within the context of the Cold War. We really became a part of the confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States and, as such, we became very, very conservative, and very, very right wing. I started changing in the 1980s when I saw that we were getting to a stage where Cuba needed a transition that was peaceful without confrontation. I no longer believed that Cuban-Americans should invade Cuba. I no longer believed that Cuban-Americans should kill other Cubans. I believe that we should work towards a transition.

But I did not make the decision to come out and be very open about it until the demise of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union disappeared, I came to the conclusion that, for the first time in the history of Cuba, Cuba could act independently of the influence of any foreign nation. In the beginning it was Spain, then it was the United States, then it was the Soviet Union. This particular moment in time was too precious not to take advantage of it. We would never achieve our own political and social maturity until Cubans were able to resolve their differences by themselves. So I became very active in the process of advocating for a dialogue with the Cuban government.

PBS: What did you then expect from the United States?

Alfredo Duran: Cubans lived under the absolute certainty that the United States would not allow a communist government to exist within 90 miles of its coast. Like most of the Cubans, we believed that the United States would take some kind of action to either invade Cuba or destabilize the Cuban government. We firmly believed that.

Looking back, of course, it did not happen. Now, I'm glad that it did not happen. It would have been very bad for the United States government to invade Cuba. It would have been very bad if the United States government destabilized the government in Cuba, the way that it was done in Guatemala and in other countries in Latin America, which essentially retarded the whole maturation process of those countries. The Cuban government has got to evolve, and it's got to change because of the activity of we Cubans, not of any foreign power.

PBS: Are many Cubans still waiting for the US to intervene?

Alfredo Duran: This whole sector of the more conservative community does. But they're wrong, because the United States will not invade Cuba. The United States is going to do what's in the best interest of the United States, and rightly so. That is what all great powers do. What we Cubans must do is make sure that we don't depend on anybody to resolve what is in our own best interest. And I don't think any activity that is sponsored by any foreign power is in the best interest of any nation. We have to resolve it by ourselves.

(2) Alfredo Duran interviewed by USA Today (15th December, 2003)

Q: Why should we believe that the Cuban dictator would allow Cubans in the island freedom and a better way of life if the US embargo is lifted, when he has done business with every other country in the world while the people of Cuba suffer? Why can't he pay his external debt to all of these countries? What good is a free education (if one can call it free) when you have no opportunities to benefit from it?

Alfredo Duran: The Cuban embargo has been in place for about 42 years. It's a policy that has not worked to achieve its stated purpose, which is to bring about a transition towards a democracy in Cuba. It's a policy that hasn't worked in the past, it's not working now, and will not work in the future. It has only served as a Berlin Wall around Cuba, to keep it from being contaminated by new political, social and economic ideas. It has also served as an excuse to the government on which to blame its failures and keep Cubans from achieving civil rights and democracy.

Q: What does your group advocate vis a vis American-Cuban relations?

Alfredo Duran: The Cuban Committee for Democracy stands for an end to the embargo, because we believe it goes against the best interest of both the United States and the Cuban nation. We also stand for normalization of relations between the United States and Cuba, and between the government of Cuba and its own people. We believe in a peaceful transition towards democracy in Cuba, and a dialogue of all Cubans on and outside the island to achieve that transition without the interference of any foreign government.

Q: I don't know anything about the Bay of Pigs Veterans Association, but I imagine it's probably a fairly conservative group. How did you go from being their president to working with the CCD?

Alfredo Duran: I came to the conclusion that it was about time that Cubans stopped killing each other. The history of Cuba has been a violent one since the beginning of the republic. At the time that the Soviet Union dissolved, I realized that it was the first time in the history of Cuba that there was no interference from any foreign power in the affairs of Cuba. First it was Spain, then the United States, then the Soviet Union. Now, no country had influence over Cuba, and it was about time that we Cubans resolved our problems by ourselves. If we're not capable of doing that, it means we have no political maturity. At that point I came out for a dialogue amongst all Cubans with the Cuban government, to try to resolve our own problems.

(3) BBC report, Cold War foes revisit battle scene (21st March, 2001)

Former enemies who fought each other 40 years ago have together revisited the site of one of the key battles of the Cold War, the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba.

The visit was the culmination of a three-day conference designed to investigate the causes of the conflict, what went so badly wrong for the US-backed forces and the lessons to be learnt from it.

Among those taking part were historians from both Cuba and the United States, Arthur Schlesinger and Richard Goodwin - both former advisers to the then US president, John Kennedy - soldiers from both sides and President Fidel Castro himself.

During the first two days in Havana previously classified documents were exchanged.

In the Cuban papers were transcripts of the telephone communications between President Castro and his military commanders during the battle.

They showed how closely involved he was, the tension of the moment and the joy when, after more than 60 hours of fighting, it became obvious that the invasion had been defeated.

The US documents chart in detail the humiliation felt at the nature of the defeat and the embarrassment caused to President Kennedy.

One State Department paper puts the blame for the debacle squarely on the CIA, which trained the invasion force.

It said: "The fundamental cause of the disaster was the Agency's failure to give the project, notwithstanding its importance and its immense potentiality for damage to the United States, the top-flight handling which it required."

It added: "There was failure at high levels to concentrate informed, unwavering scrutiny on the project."

In the aftermath of the failed mission, another US paper lays out the early plans to destabilise the Cuban government - a plan which became known as Operation Mongoose.

This included a number of bizarre schemes, including one to put powder in Fidel Castro's shoes to make his beard fall out and another which included exploding cigars.

The document suggested that the most effective commander of such an operation would be the then attorney general, the president's brother, Robert Kennedy.

Among those searching for answers in Cuba was the Kennedy's sister, Jean Kennedy Smith.

Walking the beaches of the Bay of Pigs, she said the conference had been a big boost in helping to bring peace between Cuba and the United States.

Another of the US delegates was Alfredo Duran, one of the invading force 40 years ago.

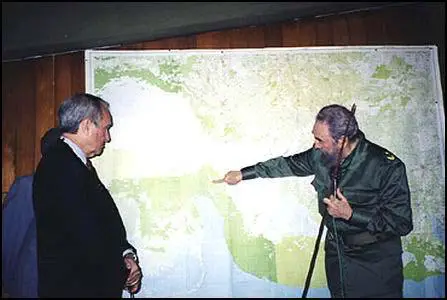

He faced the man he tried to overthrow, Fidel Castro, as well as other Cuban defenders.

As he stood on the beach he said: "This has been a very emotional time, especially discussing with the colonel in charge of the operation the very intense fighting that took place in this spot."

The beaches along the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba are now littered with sunbeds and overlooked by luxury hotels.

But there is plenty to remind the visitor that this was the scene of an important battle... as the Cubans see it the victory of a small country against an imperialist oppressor.

For the Americans it was a humiliating defeat that helped to shape its Cold War strategy for the next generation and its policy towards Cuba until now...

There was much talk at the conference of how President Kennedy was reluctant to back the invasion.

One of his former advisers who came to Havana, Arthur Schlesinger, said the president felt obliged to go ahead since he had inherited the plan from the previous Eisenhower administration.

"I advised against it," said Mr Schlesinger, "But my advice was not heeded."

In the aftermath of the failed invasion, any hopes of reconciliation with the United States died and President Castro moved closer into the Soviet camp.

The tension increased, culminating the following year in the Cuban missile crisis when the Soviet Union tried to station nuclear missiles in Cuba, pointing at the United States.

(4) Anita Snow, Cold War Adversaries Gather in Cuba (23rd March, 2001)

President Fidel Castro sat alongside ex-CIA operatives, advisers to President Kennedy and members of the exile team that attacked his country four decades ago as former adversaries met Thursday to examine the disastrous Bay of Pigs landing.

Dressed in his traditional olive green uniform, Castro read with amusement from old US documents surrounding the 1961 invasion of Cuba by CIA-trained exiles, which helped shaped four decades of U.S.-Cuba politics. Some of the documents were analyses of a young, charismatic Castro.

Castro arrived in the morning as protagonists sat down to start a three-day conference on the invasion. Participants at the meeting - which was closed the media - said he was still there in the evening.

The Cuban president personally greeted former Kennedy aide and American historian Arthur Schlesinger, but made no public statement.

Participants later said that at one point, Castro read aloud from a once secret memorandum to Kennedy about his own visit to the United States as Cuba's new leader in 1959.

"`It would be a serious mistake to underestimate this man,''' Castro read with a smile, said Thomas Blanton of the National Security Archive at George Washington University.

"With all his appearance of naiveté, unsophistication and ignorance on many matters, he is clearly a strong personality and a born leader of great personal courage and conviction,''' Castro read, according to Blanton. '``While we certainly know him better than before Castro remains an enigma.'''

Blanton said Castro told the group he believed the actual aim of the invasion was not to provoke an uprising against his government but to set the stage for a US intervention in Cuba. Blanton said a member of the former exile team, Alfredo Duran, agreed.

Among the newly declassified documents about the April 17-19, 1961, event was the first known written statement by the Central Intelligence Agency (news - web sites) calling for the assassination of Castro.

In one document released Thursday in connection with the conference, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev warned Kennedy in a letter sent the day after the invasion began that the "little war'' in Cuba" could touch off a chain reaction in all parts of the globe.''

Khrushchev issued an "urgent call'' to Kennedy to end ``the aggression'' against Cuba and said his country was prepared to provide Cuba with "all necessary help'' to repel the attack.

Trained by the CIA in Guatemala, the 2506 Brigade was comprised of about 1,500 exiles determined to overthrow Castro's government, which had seized power 28 months before.

The three-day invasion failed. Without US air support and running short of ammunition, more than 1,000 invaders were captured. Another 100 invaders and 151 defenders died.

Blanton called the conference "a victory over a bitter history.''

Other key American figures attending were Robert Reynolds, the CIA station chief in Miami during the invasion; Wayne Smith, then a US diplomat stationed in Havana; and Richard Goodwin, another Kennedy assistant, who with Schlesinger considered the invasion ill-advised.

On the Cuban government's side were Vice President Jose Ramon Fernandez, a retired general who led defending troops on the beach known here as Playa Giron, and many other retired military men.

(5) Cuban Committee for Democracy Mission Statement (2004)

The Cuban Committee for Democracy (CCD) is an organization founded in 1993 by the moderate Cuban-American community in the United States. The CCD was created to facilitate the necessary environment for a peaceful transition in Cuba to a society that unequivocally favors political pluralism and respect for civil, social, and political rights. In doing so, the Cuban Committee for Democracy will (1) promote and protect the sovereignty of the Cuban nation, (2) encourage the reconciliation of Cuban society, and (3) promote the moderate and progressive sector of the Cuban-American population.

The CCD focuses its work on the importance of dialogue and mutual respect, and applies these principles to its work with Cuba as well as within the Cuban-American community in the United States. Working within the Cuban-American community, the CCD encourages political tolerance for all opinions within the community, a basic tenet that has been missing for many years.

Since the end of the Cold War, many Cuba analysts have agreed that US policy towards Cuba is not driven by international concerns, but rather by domestic ones. Those domestic concerns reflect the success of conservative Cuban-Americans in mobilizing political support for an agenda that favors the isolation and punishment of the Cuban people because of their government.

For many years, there has been a general impression throughout the US, and especially with policymakers, that the Cuban-American community is a monolithic, uniformly conservative one that opposes all change to current US policy towards its homeland. While a large number of Cuban-Americans support this position, there are numerous and diverse opinions within the community.

Recognizing that US policy reflects the perceived opinion of this diverse community, the CCD was established to demonstrate to the Cuban-American community, to policymakers, and to Cuba that there is growing support for a reevaluation of US-Cuban relations.

The CCD believes in the sovereignty of the Cuban nation, and works to eliminate all threats to the island’s sovereignty. In the United States, these threats include official government positions and rhetoric from the Cuban-American community that condition our relationship with Cuba on specific governmental reforms. The CCD believes the Cuban people have the right to decide their future, independent of threats from other nations and communities.

The CCD believes in the reconciliation of the Cuban nation. Cubans who live on the island and Cubans who left Cuba must begin to forge a common agenda based on the future of Cuba rather than focus on differences if the nation is to progress. To do so, the CCD encourages Cuban-Americans and Cubans to forgive past wrongs, to respect political differences, and to celebrate the common links of our history and culture.

The CCD believes in promoting a peaceful transition to democracy in Cuba. Though the CCD will not make proposals for this transition, as we feel that Cubans must make such decisions, we advocate for a system that respects political, civil, and social rights. The CCD works to promote these same criteria in making democracy among the Cuban-American community a reality as well.