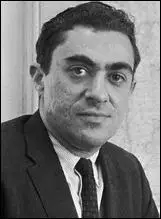

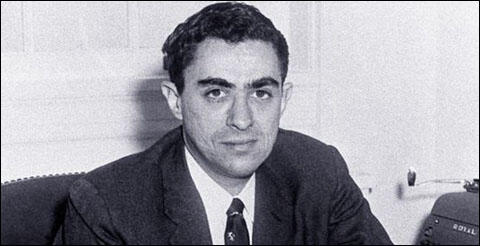

Richard N. Goodwin

Richard Naradof Goodwin was born in Boston on 7th December, 1931. He graduated from Tufts University in 1953. He then went on to study law at Harvard University.

Goodwin joined the Massachusetts State bar in 1958. He worked for Felix Frankfurter before being appointed as special counsel to the Legislative Oversight Subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives.

In 1959 John F. Kennedy appointed Goodwin as a member of his speech writing staff. The following year he became Kennedy's assistant special counsel. Goodwin was also a member of Kennedy's Task Force on Latin American Affairs and in 1961, was appointed Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, a position he held until 1963. As one of Kennedy's specialists in Latin-American affairs, Goodwin helped develop the Alliance for Progress, an economic development program for Latin America. Goodwin also served as secretary-general of the International Peace Corps.

After Kennedy's death Goodwin joined the staff of President Lyndon B. Johnson where he worked as a speechwriter and adviser. Goodwin resigned in 1965 and became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut and a visiting professor of public affairs at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Goodwin continued to be involved in politics and wrote speeches for presidential candidates Robert Kennedy, Eugene McCarthy and Edmund Muskie. He also wrote for several magazines, including The New Yorker and Rolling Stone. He also published The Fitzgeralds and the Kennedys (1986) and Remembering America (1988).

In March, 2001, Goodwin was a member of a United States delegation that visited the scene of the Bay of Pigs battle. The party included Arthur Schlesinger (historian), Robert Reynolds, (the CIA station chief in Miami during the invasion), Jean Kennedy Smith (sister of John F. Kennedy), Alfredo Duran (Bay of Pigs veteran) and Wayne S. Smith (Executive Secretary of his Latin American Task Force).

Richard Naradof Goodwin died on 20th May, 2018.

Primary Sources

(1) Seymour Hersh, The Dark Side of Camelot (1997)

Richard N. Goodwin, who wrote speeches for Kennedy during the 1960 campaign and accompanied him to the White House, described Robert Kennedy as "completely his brother's man. He was a guy whose basic purpose in life was to advance and protect the career of John Kennedy." In an interview for this book in 1997, Goodwin recalled one meeting between the president and a group of southern senators on the White House balcony. One of the senators "leaned forward and said, 'Well, Mr. President, I'm afraid I'm gonna have to attack you on civil rights: And Kennedy says, 'Can't you attack Bobby instead?' Bobby played that role," Goodwin explained. The younger Kennedy "was always reflecting his brother's feelings"

Goodwin was also present at a White House meeting after the Bay of Pigs when Bobby tore into a senior State Department official who, after the fact, had told a reporter that he was opposed to the invasion. "I watched Bobby just lash into him," Goodwin recalled. "`You can't undermine my brother." And John Kennedy just sat there quietly, never said a word throughout. But I have no doubt that Bobby was reflecting conversations that the two of them had.

(2) Anita Snow, Cold War Adversaries Gather in Cuba (23rd March, 2001)

President Fidel Castro sat alongside ex-CIA operatives, advisers to President Kennedy and members of the exile team that attacked his country four decades ago as former adversaries met Thursday to examine the disastrous Bay of Pigs landing.

Dressed in his traditional olive green uniform, Castro read with amusement from old U.S. documents surrounding the 1961 invasion of Cuba by CIA-trained exiles, which helped shaped four decades of U.S.-Cuba politics. Some of the documents were analyses of a young, charismatic Castro.

Castro arrived in the morning as protagonists sat down to start a three-day conference on the invasion. Participants at the meeting - which was closed the media - said he was still there in the evening.

The Cuban president personally greeted former Kennedy aide and American historian Arthur Schlesinger, but made no public statement.

Participants later said that at one point, Castro read aloud from a once secret memorandum to Kennedy about his own visit to the United States as Cuba's new leader in 1959.

"`It would be a serious mistake to underestimate this man,''' Castro read with a smile, said Thomas Blanton of the National Security Archive at George Washington University.

"With all his appearance of naivete, unsophistication and ignorance on many matters, he is clearly a strong personality and a born leader of great personal courage and conviction,''' Castro read, according to Blanton. '``While we certainly know him better than before Castro remains an enigma.'''

Blanton said Castro told the group he believed the actual aim of the invasion was not to provoke an uprising against his government but to set the stage for a U.S. intervention in Cuba. Blanton said a member of the former exile team, Alfredo Duran, agreed.

Among the newly declassified documents about the April 17-19, 1961, event was the first known written statement by the Central Intelligence Agency (news - web sites) calling for the assassination of Castro.

In one document released Thursday in connection with the conference, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev warned Kennedy in a letter sent the day after the invasion began that the "little war'' in Cuba" could touch off a chain reaction in all parts of the globe.''

Khrushchev issued an "urgent call'' to Kennedy to end ``the aggression'' against Cuba and said his country was prepared to provide Cuba with "all necessary help'' to repel the attack.

Trained by the CIA in Guatemala, the 2506 Brigade was comprised of about 1,500 exiles determined to overthrow Castro's government, which had seized power 28 months before.

The three-day invasion failed. Without U.S. air support and running short of ammunition, more than 1,000 invaders were captured. Another 100 invaders and 151 defenders died.

Blanton called the conference "a victory over a bitter history.''

Other key American figures attending were Robert Reynolds, the CIA station chief in Miami during the invasion; Wayne Smith, then a U.S. diplomat stationed in Havana; and Richard Goodwin, another Kennedy assistant, who with Schlesinger considered the invasion ill-advised.

On the Cuban government's side were Vice President Jose Ramon Fernandez, a retired general who led defending troops on the beach known here as Playa Giron, and many other retired military men.

(3) BBC report, Cold War foes revisit battle scene (21st March, 2001)

Former enemies who fought each other 40 years ago have together revisited the site of one of the key battles of the Cold War, the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba.

The visit was the culmination of a three-day conference designed to investigate the causes of the conflict, what went so badly wrong for the US-backed forces and the lessons to be learnt from it.

Among those taking part were historians from both Cuba and the United States, Arthur Schlesinger and Richard Goodwin - both former advisers to the then US president, John Kennedy - soldiers from both sides and President Fidel Castro himself.

During the first two days in Havana previously classified documents were exchanged.

In the Cuban papers were transcripts of the telephone communications between President Castro and his military commanders during the battle.

They showed how closely involved he was, the tension of the moment and the joy when, after more than 60 hours of fighting, it became obvious that the invasion had been defeated.

The US documents chart in detail the humiliation felt at the nature of the defeat and the embarrassment caused to President Kennedy.

One State Department paper puts the blame for the debacle squarely on the CIA, which trained the invasion force.

It said: "The fundamental cause of the disaster was the Agency's failure to give the project, notwithstanding its importance and its immense potentiality for damage to the United States, the top-flight handling which it required."

It added: "There was failure at high levels to concentrate informed, unwavering scrutiny on the project."

In the aftermath of the failed mission, another US paper lays out the early plans to destabilise the Cuban government - a plan which became known as Operation Mongoose.

This included a number of bizarre schemes, including one to put powder in Fidel Castro's shoes to make his beard fall out and another which included exploding cigars.

The document suggested that the most effective commander of such an operation would be the then attorney general, the president's brother, Robert Kennedy.

Among those searching for answers in Cuba was the Kennedy's sister, Jean Kennedy Smith.

Walking the beaches of the Bay of Pigs, she said the conference had been a big boost in helping to bring peace between Cuba and the United States.

Another of the US delegates was Alfredo Duran, one of the invading force 40 years ago.

He faced the man he tried to overthrow, Fidel Castro, as well as other Cuban defenders.

As he stood on the beach he said: "This has been a very emotional time, especially discussing with the colonel in charge of the operation the very intense fighting that took place in this spot."

The beaches along the Bay of Pigs in southern Cuba are now littered with sunbeds and overlooked by luxury hotels.

But there is plenty to remind the visitor that this was the scene of an important battle... as the Cubans see it the victory of a small country against an imperialist oppressor.

For the Americans it was a humiliating defeat that helped to shape its Cold War strategy for the next generation and its policy towards Cuba until now...

There was much talk at the conference of how President Kennedy was reluctant to back the invasion.

One of his former advisers who came to Havana, Arthur Schlesinger, said the president felt obliged to go ahead since he had inherited the plan from the previous Eisenhower administration.

"I advised against it," said Mr Schlesinger, "But my advice was not heeded."

In the aftermath of the failed invasion, any hopes of reconciliation with the United States died and President Castro moved closer into the Soviet camp.

The tension increased, culminating the following year in the Cuban missile crisis when the Soviet Union tried to station nuclear missiles in Cuba, pointing at the United States.