On this day on 6th June

On this day in 1762 John Wilkes writes about the freedom of the press. In 1762, the new king, George III, arranged for his close friend, the Earl of Bute, to become prime minister. This decision upset a large number of MPs who considered Bute to be incompetent. John Wilkes became Bute's leading critic in the House of Commons. In June 1762 Wilkes established The North Briton, a newspaper that severely attacked the king and his Prime Minister.

In his first issue Wilkes wrote "the liberty of the press is the birthright of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country". In the edition published on 23rd April 1763, he said the king's speech at the opening of Parliament gave "his sacred name to the most odious measures and the most unjustifiable public declarations from a throne ever renowned for truth, honour and the unsullied virtue." He added that the "spirit of discord" will "never be extinguished, but by the extinction of their power".

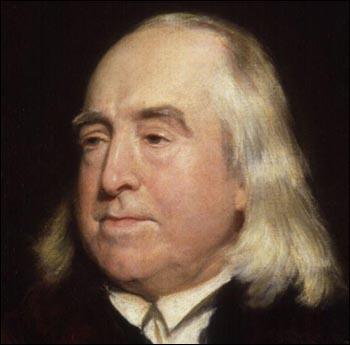

On this day in 1832 philosopher Jeremy Bentham died. Jeremy Bentham, the son of a lawyer, was born in London on 15th February 1748. A brilliant scholar, Bentham entered Queen's College, Oxford at twelve and was admitted to Lincoln's Inn at the age of fifteen. Bentham was a shy man who did not enjoy making public speeches. He therefore decided to leave Lincoln Inn and concentrate on writing. Provided with £90 a year by his father, Bentham produced a series of books on philosophy, economics and politics.

Bentham's family had been Tories and for the first period of his life he shared their conservative political views. This changed after Bentham read the work of Joseph Priestley. One statement in particular from The First Principles of Government and the Nature of Political, Civil and Religious Liberty (1768) had a major impact on Bentham: "The good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of the state, is the great standard by which every thing relating to that state must finally be determined."

Another important influence on Bentham was the philosopher David Hume. In books such as A Fragment on Government (1776) and Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (1789), Bentham argued that the proper objective of all conduct and legislation is "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". According to Bentham, "pain and pleasure are the sovereign masters governing man's conduct". As the motive of an act is always based on self-interest, it is the business of law and education to make the sanctions sufficiently painful in order to persuade the individual to subordinate his own happiness to that of the community.

In 1798 Jeremy Bentham wrote Principles of International Law where he argued that universal peace could only be obtained by first achieving European Unity. He hoped that some form of European Parliament would be able to enforce the liberty of the press, free trade, the abandonment of all colonies and a reduction in the money being spent on armaments.

In Catechism of Reformers (1809) Bentham criticised the law of libel as he believed it was so ambiguous that judges were able to use it in the interests of the government. Bentham pointed out that the authorities could use the law to punish any Radical for "hurting the feelings" of the ruling class. Bentham also attacked other aspects of the legal system such as "jury packing".

Radical reformers such as Sir Francis Burdett, Leigh Hunt, William Cobbett, and Henry Brougham praised Bentham's work. Although written in a complex style, radical publishers attempted to communicate his ideas to the working class. Thomas Wooler published extracts in his journal Black Dwarf and eventually published a cheap edition of Catechism of Reformers. When Burdett introduced a series of resolutions in the House of Commons in July 1818, demanding universal suffrage, annual parliaments and vote by ballot, he quoted the writings of Jeremy Bentham to support his case.

In 1824 Bentham joined with James Mill (1773-1836) to found the Westminster Review, the journal of the philosophical radicals. Contributors to the journal included Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Thomas Carlyle.

Bentham's most detailed account of his ideas on political democracy appeared in his book Constitutional Code (1830). In the book Bentham argued that political reform should be dictated by the principal that the new system will promote the happiness of the majority of the people affected by it. Bentham argued in favour of universal suffrage, annual parliaments and vote by ballot. According to Bentham there should be no king, no House of Lords, no established church. The book also included Bentham's view that women, as well as men, should be given the vote.

In Constitutional Code Bentham also addressed the problem of how government should be organised. For example, he suggested the introduction of rules that would ensure the regular attendance of members of the House of Commons. Government officials should be selected by competitive examination. The book also suggested the continual inspection of the work of politicians and government officials. Bentham pointed out they should be continually reminded that they are the "servants, not the masters, of the public".

Jeremy Bentham

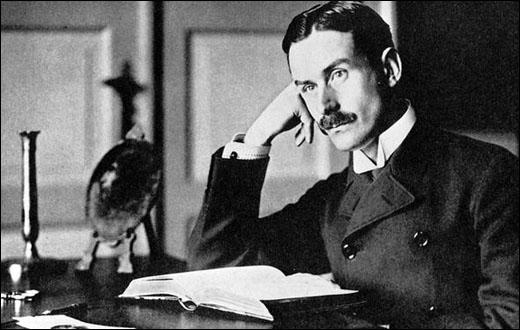

On this day in 1862 Henry Newbolt was born. Newbolt was born in Bilston, Staffordshire, in 1862. After studying at Clifton School and Oxford University, became a barrister. He published his first novel, Taken from the Enemy, in 1892. This was followed by Mordred: A Tragedy, in 1895. He also published two volumes of poetry, Admirals All (1897) and The Island Race (1898).

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War, Newbolt was recruited by Charles Masterman, the head of Britain's War Propaganda Bureau (WPB), to help shape public opinion. Newbolt, who was controller of telecommunications during the war, also published The Naval History of the Great War (1920). He was knighted in 1915 and awarded the Companion of Honour in 1922.Sir Henry Newbolt died in 1938.

On this day in 1875 Thomas Mann, the son of Thomas Johann Mann and Júlia da Silva Bruhns, was born in Lübeck, Germany, on 6th June, 1875. He later wrote that his "childhood was sheltered and happy".

Mann's father was an energetic and successful businessman. In 1863, at the age of 23, had inherited the ownership of the Johann Siegmund Mann firm, a granary and shipping business dating back to the previous century. His brother, Heinrich Mann, remembered his father as "young, gay, and carefree."

Thomas Mann later recalled his father's "dignity and good sense, his ambition and industry, his personal and intellectual distinction, his social talents and his humor... he was not robust, rather nervous and susceptible to suffering; but he was a man dedicated to self-control".

Júlia Mann had been born in South America and was the daughter of a German planter who had married a Creole woman of Portuguese and Indian ancestry. She was considered to be Lübeck's most beautiful woman and was described as "a much admired beauty and extraordinarily musical". Thomas claimed that "with the ivory complexion of the South, a nobly sculpted nose, and the most attractive mouth I ever encountered".

Thomas Mann attended Dr. Bussenius's private elementary school from 1882 to 1889. He then progressed to the Lübeck Gymnasium. Mann later recalled that he "loathed school". Thomas spent his time reading, writing or dreaming. However, he found school much more difficult than his brother, Heinrich, who received consistently good grades but upset his father by refusing to go to university.

Although less talented than his brother, Thomas received praise from his father: "My second son (Thomas) is responsive to calm admonishments; he has a good disposition and will find his way to a practical vocation. I feel justified in expecting that he will be a support to his mother."

Heinrich Mann refused to join the family business and in October 1889, he was employed by the Dresden book shop of Jaensch & Zahn as an apprentice. Thomas Johann Mann was deeply upset by this rejection and when he died in June 1891 he left instructions for the family granary and shipping business to be liquidated.

After the death of his father, Mann and his mother moved to Munich, where he started work with an insurance firm. He decided on a literary career and contributed to Simplicissimus, the well-known satirical weekly. Started in 1896 by Albert Langen, it employed the cartoonist, Thomas Heine and several talented writers such as Frank Wedekind and Rainer Maria Rilke.

A supporter of liberal causes, Simplicissimus appeared revolutionary when compared to established journals such as Kladderadatsch. It especially upset the German government by objecting to a law in 1897 that penalized striking workers. It also supported trade unionists in their struggle with employers during this period. In 1898, after objections by Wilhelm II, both Heine (six months) and Wedekind (seven months) were imprisoned for their attack on the German monarchy.

Heinrich Mann was also keen to become a writer. Both men greatly admired the work of Heinrich Heine: "In his enthusiasm for Heine, in trying his hand at verse, fiction, and criticism, Thomas at this time was faithfully following in the footsteps of his elder brother. His youthful revolt against society, natural though it was for his age, seems also to have been borrowed from his brother, who was bohemian by instinct". Heinrich had several novels published but it was not until the appearance of In the Land of Cockaigne (1900), a portrayal of the decadence of high society, that he received any recognition as a writer.

Thomas Mann had been working on a novel, a fictional account of the Mann family, for several years. He decided to start the story in 1835 when the Johann Siegmund Mann company was established and to record the growth and decline over four decades. He researched the book by interviewing elderly relatives. Wilhelm Marty, his father's cousin, later recalled that he had asked about "business cycles and the rise and fall of grain prices, about the possible reasons for the decline of a grain firm, and even about the kind of street lighting Lübeck had" before he had been born.

On the verge of submitting his manuscript, he experienced a loss of confidence. "Whole chapters at the beginning, which now strike me as repulsively stupid, will have to be reworked". The novel was finished in June 1900. He wrote to his friend, Paul Ehrenberg: "I shall probably have to throw it into my publisher's maw for a song. Money and mass applause are not to be won with such books."

Thomas Mann sent his manuscript to Samuel Fischer, a publisher in Berlin. Fischer wanted to publish the book but wanted it reduced by at least 50%. Mann refused, but told him that if he published the book as it, he can dictate your terms. Fischer agreed to publish it uncut in two volumes, but with no advance payment. Thomas was not convinced the book was going to be a success and he wrote to his brother, Heinrich, complaining "you are flourishing while at the moment I am going to pieces".

Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family (1901) received a good review from Rainer Maria Rilke, who praised the novel's "realistic detail". But others claimed that the book lacked structure or was insufficiently dramatized. The novel sold slowly in the first nine months but sales picked up after it was written about by the well-known critic, Samuel Lublinski in the Berliner Tageblatt. He considered it an outstanding achievement that would become a classic and "read by many generations".

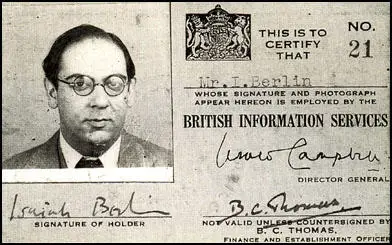

On this day in 1909 Isaiah Berlin, the only child of Mendel Borisovitch Berlin and Marie Volshonok Berlin, was born in Riga, Latvia, on 6th June 1909. It was a difficult birth and the doctor placed forceps on his left arm and yanked him into the world so violently that the ligaments were permanently damaged. His father was a prosperous timber merchant whose main business was supplying wooden sleepers for the Russian railways.

During the First World War the family moved to Saint Petersburg. He did not attend school and was educated at home. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks nationalised the railways and his father was employed as a state contractor. His biographer, Alan Ryan, has pointed out: "There Berlin saw the brutality of revolution at first hand. He was horrified by the spectacle of a mob hounding a policeman in the street, and dragging him off to his presumed death. In later years he maintained that his hatred of political violence had its origins in that experience, though it was very far from making him a pacifist. Antisemitism was never far below the surface of the Soviet revolution, and it was a constant threat during the subsequent civil war. Nevertheless the Berlins fared no worse and no better than most other middle-class Russians who found their homes requisitioned and their lives threatened by the ubiquitous informers who hoped to advance themselves by denouncing their neighbours."

In 1919 the Cheka ransacked their home. Mendel Berlin now made the decision to leave the capital: "The feeling of being imprisoned, no contact with the outside world, the spying all round, the sudden arrests and the feeling of absolute helplessness against the whim of any hooligan parading as a Bolshevik". The family moved back to Latvia, now an independent republic. At the Latvian-Soviet border, the Jews were taken off the train and were sent to a Russian bath for delousing. Isaiah later recalled: "We were Jews... we were not Russian... we were something else."

Mendel Berlin established himself in the timber trade but it was decided to emigrate to Britain. In February 1921 the family arrived in London. They rented a home in Surbiton and Isaiah attended the Arundel House School. As Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "The loneliness of a child exiled into a foreign tongue is easy to imagine. English schoolboy lore - football teams, cartoon characters, dirty songs and jokes, snobberies and cruelties - was beyond his ken, while all the impressive things he knew seemed worthless or an embarrassment."

Isaiah Berlin was occasionally called a "dirty Jew" but he was impressed by the way the other boys protected him from these outbreaks of prejudices. He was never to forget these acts of kindness that he insisted this was "deeply and uniquely English". He later wrote "that decent respect for others and the toleration of dissent is better than pride and a sense of national mission; that liberty may be incompatible with, and better than, too much efficiency; that pluralism and untidiness are, to those who value freedom, better than the rigorous imposition of all-embracing systems, no matter how rational and disinterested, better than the rule of majorities against which there is no appeal."

Mendel Berlin was successful in the timber trade and in 1922 the family moved into a three-storey terraced house in Upper Addison Gardens, Holland Park. However, Isaiah later recalled that his mother was not happy: "She resented being married to him. Felt he was dull, depended on her. She wanted to be loved, she wanted to be lifted, nothing ever happened, so all her love was turned on me." Marie Berlin was more interested in politics than her husband and was chairwoman of the Brondesbury Zionist Society.

Isaiah Berlin attended St Paul's School. In 1927 he sat the examination for Corpus Christi College and won an entrance scholarship in classics. At university he made friends with Stephen Spender, Bernard Spencer, Goronwy Rees, Victor Rothschild, W.H. Auden, Arthur Calder-Marshall, John Langshaw Austin, Stuart Hampshire, Sheila Lynd and Shiela Grant Duff. Another friend, Diana Hubback, said that he "seemed completely adult at a time when his youthful friends were only just emerging from adolescence." In 1930 inherited the editorship of Oxford Outlook , an undergraduate magazine, from Calder-Marshall.

Berlin was impressed by his philosophy tutor, Frank Hardie, who taught him how to think clearly: "Obscurity and pretentiousness and sentences which doubled over themselves he wrung right out of me, from then until this moment." Michael Ignatieff has argued: "Hardy became the single most important intellectual influence upon Berlin's undergraduate life: orienting him towards the British empiricism that became his intellectual morality. It was remarkable that someone so undisciplined and intuitive should have realised how much he needed what the mild, retiring Scotsman had to teach him. But this was to prove a lifetime pattern: seeing in others what he lacked himself, and having the shrewdness and self-confidence to go in search of it."

In 1931 Berlin developed a close friendship with Maurice Bowra, the Dean of Wadham College. During this period Bowra liked to portray himself as the "leader of the immoral front front, all those communists, homosexuals and non-conformists who stood for pleasure, conviction and sincerity against the dull, fastidious mandarins of the Oxford senior common rooms." Berlin later recalled "the words came in short sharp bursts of precisely aimed, concentrated fire as image, pun, metaphor, parody, seemed spontaneously to generate one another in a succession of marvellously imaginative patterns, sometimes rising to high, wildly comical fantasy."

Berlin gained a first-class degree in Greats and the John Locke Prize in philosophy. He considered going into journalism but was not offered a job after being interviewed by C.P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian. As a result he returned to the University of Oxford to read Philosophy, Politics and Economics. During this period he became friends with some interesting figures such as Virginia Woolf, Victor Rothschild, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, W.H. Auden, Douglas Jay, Peggy Garnett and David Astor.

A. J. Ayer described meeting Berlin in his autobiography, Part of My Life (1977): "It was through the Jowett Society that I came to know Isaiah, or as his friends then called him, Shaya Berlin. We already had a slight connection in that his father, who came from Riga, was also in the timber trade and knew both my father and my father's partner Mr Bick, but although we had known of each other through the Bicks, we had never met. Isaiah had gone to school at St Paul's and had come up to Oxford a year ahead of me as a classical scholar at Corpus. Andrew and I called on him in the belief that a meeting of the Jowett Society was being held in his rooms, but either we had been misinformed, or the venue of the meeting had been changed, and we found him alone.... On this occasion, we had hardly begun talking before I said to Andrew, "Let's not go to the meeting. This man is much more interesting." Not caring to be treated as if he had been put on show, Isaiah hustled us away to the meeting, but this was the beginning of a friendship that has lasted for over forty years."

Ayer added: "One of the things that first brought us together was our common interest in philosophy. This is an interest that we no longer share, since Isaiah was persuaded by the American logician H. M. Sheffer, in the early nineteen-forties, that the subject had developed to a point where it required a mastery of mathematical logic which was not within his grasp: thereafter he chose to cultivate the lusher field of political theory. His approach to philosophy had indeed always been more eclectic than mine and more critical than constructive. In our frequent discussions, his part was usually to find unanswerable objections to the extravagant theories that I advanced. He once described me to a common friend as having a mind like a diamond, and I think it is true that within its narrower range my intellect is the more incisive. On the other hand, he has always had the readier wit, the more fertile imagination and the greater breadth of learning. The difference in the working of our minds is matched by a difference in temperament, which has sometimes put a strain upon our friendship. I am more resilient, more reckless and more intolerant; he is more mature, more expansive and more responsible. At times he has found me too theatrical and been shocked by my sensual self-indulgence. I have sometimes wished that he were more revolutionary in spirit. I credit us both with a strong moral sense, but it expresses itself in rather different ways."

In October 1932 Berlin was given a post as tutor in philosophy in New College. He later recalled: "I knew I wasn't first rate, but I was good enough. I was quite respected. I wasn't despised." One of his students was Richard Crossman. The two men did not get on. Berlin later argued that: "Crossman was a left-wing Nazi. He was anti-capitalist, hated the civil service, respectability, conventional values, of a decent honest dreary kind. What he wanted was young men singing songs, students linking arms, torchlit parades. There was a strong fascist streak in him. He wanted power, hated liberalism, mildness, kindness, amiability."

Berlin's first book, Karl Marx: His Life and Environment, was published in 1939. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has argued: "Berlin never mastered Marx's economic theory in Das Kapital. Yet he took pride in getting inside the head of an antipathetic figure, and in a larger sense, the sojourn with Marx had a profound influence on his later thought. It gave him a lifelong target, for he genuinely loathed Marxian ideas of historical determinism and was to argue that they served as the chief ideological excuse for Stalin's crimes. At the same time, he was influenced by the Marxian sense that ideas and values were historical, and that the values of social groups in class struggle were incompatible." Alan Ryan has pointed out: "The book was both a publishing success and a double landmark in Berlin's life. In the first place, it was one of the first works in English that treated Marx absolutely objectively - neither belittling the real intellectual power of his work, nor descending into hagiography. Second, it revealed Berlin's unusual talent as a historian of ideas - or more exactly as a biographer of ideas. Berlin was no admirer of Marx, and wholly deplored the political consequences of his ideas, but he entered into the intellectual world of Marx and his fellow revolutionaries as few biographers have known how to do."

Isaiah Berlin had broken off contact with Guy Burgess when he had joined Britannia Youth, a neo-fascist group that sent British schoolboys to Nazi Party rallies in Germany. However, in June 1940, Burgess arrived in Berlin's rooms at New College to apologize for his behaviour: "I'm terribly unstable, it just came over me. Everything in England was so dreary. I thought at least the Nazis knew where they were going. Anyway I don't expect you to forgive me." Burgess then revealed that Harold Nicolson had recruited him to undertake a mission to the Soviet Union on behalf of MI5.

Berlin agreed to the proposal but when they got to Quebec Burgess was recalled to London. Berlin now went to New York City where he visited his friends, Felix Frankfurter and Reinhold Niebuhr. He also contacted Richard Stafford Cripps and volunteered his services to the war effort. Cripps recommended he returned to England to receive further orders. After a meeting in the Ministry of Information, Berlin received instructions to join the British Security Coordination (BSC).

Berlin arrived in New York City in January 1941. Michael Ignatieff, the author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) has pointed out: "Isaiah Berlin's job was to get America into the war. He was to be a propagandist, working with trade unions, black organizations and Jewish groups. He lived in mid-town Manhattan hotels and went to work every morning at the British Information Services on the forty-fourth floor of a building in the Rockefeller Center. There he went through piles of American press clippings ranged in shoe-boxes. From these he put together a weekly report for the Ministry of Information on the state of American public opinion. In the early months of 1941 the isolations were in the ascendant and the prospects of getting America into the war seemed remote."

Daphne Straight, who worked in the same office as Berlin described him as a "voluble, slightly mad professor - pockets overflowing with sweets, handkerchiefs, press cuttings, lapels dusted with cigarette ash". He visited editors and tried to persuade them to publish articles that provided a positive image of Britain. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Berlin also worked closely with supporters of American intervention in the Second World War. This included Rabbi Stephen Wise and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandelis. Other contacts included Sidney Hillman and David Dubinsky, the leaders of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA).

Berlin was also instructed to work on Arthur Hays Sulzberger who was being criticised by the British government for not supporting the cause as well as the New York Herald Tribune. One of Berlin's colleagues, Valentine Williams had a meeting with Sulzberger and on 15th September, 1941. That night he reported to Hugh Dalton, Minister of Economic Warfare: "I had an hour with Arthur Sulzberger, proprietor of the New York Times, last week. He told me that for the first time in his life he regretted being a Jew because, with the tide of anti-semitism rising, he was unable to champion the anti-Hitler policy of the administration as vigorously and as universally as he would like as his sponsorship would be attributed to Jewish influence by isolationists and thus lose something of its force." He also suggested to Berlin, who lobbied Sulzberger to be more outspoken about the treatment of Jews in Nazi Germany: "Mr Berlin, don't you believe that if the word Jew was banned from the public press for fifty years, it would have a strongly positive influence."

Berlin also had regular meetings with journalists such as Drew Pearson, Walter Lippman, Philip Graham, Joseph Alsop, Arthur Krock and Marquis Childs, in an effort to publish information favourable to the British. Berlin took Harold Ross, the editor of the New Yorker, to lunch at the Algonquin Hotel. At the end of the lunch Ross commented: "Young man, I can't understand a word you say, but if you write anything, I'll print it." Despite his efforts, by the end of 1941, 80% of the American public was still opposed to the sending of American troops to Europe.

In 1942 Berlin was transferred from New York City to Washington, and for the remainder of the war drafted reports on behalf of Lord Halifax, who had succeeded Lord Lothian as British ambassador. Berlin had a good relationship with Halifax although he was "not of this century" and was like "a creature from another planet". These reports were read by Winston Churchill and Anthony Eden. His biographer, Alan Ryan has commented that "Berlin walked with some skill the fine line between exact reporting and colouring the news to enhance the prospects of a desired policy. It was a skill he especially needed to preserve relations with Chaim Weizmann and other Zionist friends. He was happy to do what he could to keep doors in both the American and British governments open for his friends, but he was also acutely aware of Foreign Office doubts about Zionist aspirations. He took care neither to betray his friends nor to destroy his own usefulness by becoming an object of suspicion to his employers, although in 1943 he was instrumental in obstructing a joint British-American declaration against the establishment of a post-war Jewish state." During this period he spent a lot of time at the home of Chip Bohlen on Dunbarton Avenue. George Kennan was also a regular visitor and one observer described the three men as "a homogeneous, congenial trio."

In February 1944, an article appeared in New York Post by Edgar Ansel Mowrer, that claimed that the Allies were "passively permitting the extermination of the European Jews when they could be saving a large number of them". Berlin was involved in drafting a reply to these charges: "The British and American governments are doing everything in their power, by warnings to Hitler and by negotiations with the neutrals, to put a stop to this massacre and to assist in the escape of its victims. For obvious reasons the full extent of their activity cannot be made public."

On 8th September 1945, Berlin, taken advantage of the fact that the Soviet Union was now an ally of Britain, flew to Moscow in order to visit relatives he had not seen since leaving the country 25 years earlier. He was told by his cousins that anti-Semitism, in abeyance during the war, was now making a return. Berlin also had meetings with Sergi Eisenstein, who had been dismissed from the Kamerny Theatre by Joseph Stalin.

Berlin had a meeting with the novelist, Boris Pasternak. He told him the story how Stalin phoned him in 1934 and asked him about the poem that Osip Mandelstam had read at a small private gathering in Moscow. Pasternak claimed that he was unable to remember if the poem was an attack on Stalin. Unconvinced by his answer, Stalin interjected, "If I were Mandelstam's friend I should have known better how to defend him." Mandelstam was sent to a labour camp and died in December 1938.

Berlin also arranged to visit Mikhail Zoshchenko, the successful author of Tales (1923), Esteemed Citizens (1926), What the Nightingale Sang (1927) and Nervous People (1927). Zoshchenko satires were popular with the Russian people and he was one of the country's most widely read writers in the 1920s. Although Zoshchenko never directly attacked the Soviet system, he was not afraid to highlight the problems of bureaucracy, corruption, poor housing and food shortages. In the 1930s Zoshchenko came under increasing pressure to conform to the idea of socialist realism.

During the Second World War Mikhail Zoshchenko was expelled to Tashkent with the poet, Anna Akhmatova. However, his exile had made him very ill and Berlin, who described him as "yellow of complexion, withdrawn, incoherent, pale, weak and emaciated", shook his hand but did not have the heart to engage him in conversation. However, he did spend a long time with Akhmatova and it was the beginning of a long-term friendship.

Berlin returned to his post as tutor in philosophy in New College. The author of A Life of Isaiah Berlin (1998) points out that he had an unusual style of teaching: "He was an eccentric teacher, often taking tutorials in pyjamas and dressing-gown, or actually in bed... He didn't bore his students, but they often bored him." In 1946 he wrote that his students were "dull and polite and spiritless with too much army life in them, scores and scores of them cluttering up every available chink of time and space, morning and afternoon and evening."

Berlin moved to the right in the 1940s and fell out with several friends who still remained on the left. He was invited to the United States to give lectures on the Cold War. In one lecture, Democracy, Communism and the Individual , Berlin argued that the terms "liberty, equality and fraternity" were "beautiful but incompatible". Despite this the New York Times published an article falsely claiming that he was urging American universities to take up Marxist studies. This resulted in the FBI making inquiries about his political past.

In 1949 Berlin gave a talk on BBC radio where he argued that Britain must recognise that its ultimate interests lay neither with the British Empire nor with Europe but with the United States. The speech was attacked by those on the right like Lord Beaverbrook, who wrote in the Evening Standard about his defeatism about the empire and his subservience towards the Americans. He was also criticised by those on the left like Harold Laski and G.D.H. Cole, who disliked his commitment to American capitalism. Berlin, who had always voted for the Labour Party, changed to the Liberal Party in the 1950 General Election. He considered supporting Winston Churchill but "he was too coarse, too brutal, and I didn't want him back in."

Although he was a fervent anti-communist, Berlin disapproved of McCarthyism. He wrote to a friend: "I am indeed anti-communist, but perhaps when heretics are being burnt right and left it is not the bravest thing in the world to declare one's loyalty to the burners, particularly when one disapproves of the Inquisition." When his friend, Robert Oppenheimer, was denied a security clearance because of his alleged communist sympathies, Berlin joined others in writing letters of protest.

When his friend, Guy Burgess, fled to the Soviet Union in June 1951, Berlin was a willing informer on his left wing associates. Peter Wright of MI5 wrote that "Isaiah Berlin and Arthur Marshall, were wonderfully helpful, and met me regularly to discuss their contemporaries at Oxford and Cambridge... Berlin had a keen eye for Burgess' social circle, particularly those whose views appeared to have changed over the years. He also gave me sound advice on how to proceed with my inquiries." Berlin also told Wright to investigate Anthony Blunt: "Anthony's trouble is that he wants to hunt with society's hounds and run with the Communist hares!" However, another friend from university, Goronwy Rees, gave an interview to The People newspaper suggesting that Berlin might have been working for Burgess in the 1930s.

Berlin wrote several articles about the danger of communism for Foreign Affairs, that obtained praise from Henry Luce. He also wrote for Encounter Magazine that was covertly funded by the CIA. He later recalled: "I was (and am) pro-American and anti-Soviet, and if the source had been declared I would not have minded in the least... What I and others like me minded very much was that a periodical which claimed to be independent, over and over again, turned out to be in the pay of American secret Intelligence."

His biographer, Alan Ryan, has argued: "Berlin enjoyed the company of women, but thought himself sexually unattractive, and believed until his late thirties that he was destined to remain a bachelor. All Souls was a luxurious bachelor society, and Berlin's affection for his mother was sufficient to suggest that he would neither be driven into marriage by the discomforts of single life nor lured into it by the need for stronger emotional attachments than the unmarried life provided. It was therefore somewhat to the surprise of his numerous friends that on 7th February 1956 he married Aline Elisabeth Yvonne Halban, the daughter of the banker Baron Pierre de Gunzbourg, of Paris. He thereby acquired three stepsons as well as a beautiful and well-connected wife whose accomplishments had included the women's golf championship of her native France. They established themselves in Aline's substantial and elegant house on the outskirts of Oxford (Headington House, nicknamed Government House by Berlin's more left-wing friends), and there they lived and entertained - or, as the same friends had it, held court - for the next forty years. Although he had embarked on marriage rather late, Berlin never ceased to recommend the married condition, and his happiness was a persuasive advertisement for what he preached."

On 31st October 1958, Berlin gave a lecture at the University of Oxford entitled Two Concepts of Liberty : "Everything is what it is: liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience. If the liberty of myself or my class or nation depends on the misery of a number of other human beings, the system which promotes this is unjust and immoral. But if I curtail or lose my freedom, in order to lessen the shame of such inequality, and do not thereby materially increase the individual liberty of others, an absolute loss of liberty occurs. This may be compensated for by a gain in justice or in happiness or peace, but the loss remains, and it is a confusion of values to say that although my 'liberal' individual freedom may go by the board, some other kind of freedom - social or economic - is increased."

Conservatives such as Leo Strauss and Alan Bloom welcomed Berlin's critique of the totalitarian temptation. However, he was attacked by the Canadian philosopher, Charles Taylor who argued that self-realisation did not necessarily lead to totalitarian tyranny and that individuals could use their freedom to transform themselves through knowledge and self-understanding. Taylor added that Berlin's defence of liberty was little more than a mere apologia for free-market capitalism.

Berlin had seen an early draft of Dr. Zhivago. He told Boris Pasternak that he should not publish the book, with the words that "martyrdom was a moral temptation like any other and should be resisted". Pasternak disagreed and the book was published in Italy in 1958. The Soviet regime was furious and began the harassment that Berlin believed contributed to his early death in 1960.

Berlin upset his left-wing friends by refusing to join the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. In May 1961, when President John F. Kennedy administration sponsored the abortive Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, Berlin refused to sign a statement condemning the operation. He argued that Fidel Castro "may not be a Communist but I think he cares as little for civil liberties as Lenin or Trotsky." Perry Anderson of the New Left Review attacked him as being one of the "European immigrants to Britain who had done most to serve up to the English a self-congratulatory picture of their own supposedly liberal virtues."

In 1961 E. H. Carr, made an attack on Berlin's idea that historians should be chiefly concerned not with explanation but with moral evaluation. Surely, Carr argued, no one seriously supposed that a historian's task was to bother with the question of whether Oliver Cromwell or Adolf Hitler were "bad fellows". Their task was rather to understand the factors that he enabled them to come to power and the forces which their rule unleashed. Berlin replied that Marxist theory put an almost exclusive emphasis on abstract socio-economic causation and neglected the importance of the ideas, beliefs and intentions of individuals.

Berlin was invited to attend a small private dinner in honour of Charles Bohlen in October 1962. Other people invited included President John F. Kennedy, Philip Graham, Joseph Alsop and Arthur Schlesinger. During the dinner Kennedy asked Berlin about what the Soviets do when "backed into a corner". Berlin later recalled: "I've never known a man who listened to every single word that one uttered more attentively. His eyes protruded slightly, he leant forward towards one, and one was made to feel nervous and responsible by the fact that every word registered."

After the Cuban Missile Crisis Kennedy told Berlin that the incident would never expunge the stain of Cuba No. 1 (Bay of Pigs). He asked Berlin to conduct a seminar on communism. This took place on 12th December, 1962. The seminar was attended by McGeorge Bundy, Robert McNamara, Arthur Schlesinger, Robert Kennedy and Walt Rostow. Berlin attempted to explain how communism imported into Europe as a "secular, theoretical, abstract doctrine" was transformed by its contact with the earnest Russian intelligentsia into Leninism, as a "fiery, sectarian, quasi-religious faith".

In 1963, the Marxist academic, Isaac Deutscher, was being considered for a professorship in political studies at Sussex University. Berlin, who served on the university's academic advisory board, was asked by the Vice-Chancellor for his opinion on Deutscher. His comment, that Deutscher was "the only man whose presence in the same academic community as myself I should find morally intolerable" meant that he was not offered the post. Berlin was embarrassed when this letter was published in Black Dwarf in 1969 and he was denounced as an anti-communist witch-hunter.

In 1966 Berlin became president of Wolfson College. Under the name Iffley College, this had been a new and under-financed graduate college. It was renamed Wolfson College in acknowledgement of the generosity of Sir Isaac Wolfson's Foundation, which paid the cost of the new building. It also received funding from the Ford Foundation. He held the post for the next nine years.

In 1967 Berlin was asked to contribute to Authors Take Sides on Vietnam, a collection of statements about the Vietnam War. Berlin upset both right and left when he argued that the Americans should not have intervened but, having sent in troops, they should not withdraw precipitously, lest the South Vietnamese be massacred by communist forces. He also suggested that he supported the idea of the domino theory and that if South Vietnam was lost the other pro-Western regimes in the region would also fall.

Berlin argued: "Happy are those who live under a discipline which they accept without question, who freely obey the orders of leaders, spiritual or temporal, whose word is fully accepted as unbreakable law; or those who have, by their own methods, arrived at clear and unshakeable convictions about what to do and what to be that brook no possible doubt. I can only say that those who rest on such comfortable beds of dogma are victims of forms of self-induced myopia, blinkers that may make for contentment, but not for understanding of what it is to be human."

At the age of seventy Berlin relinquished all his public positions except his seat on the Covent Garden Board and his place as a trustee of the National Gallery. With the help of Henry Hardy, Berlin published a series of books made up of old and new articles. This included Vico and Herder: Two Studies in the History of Ideas (1976), Russian Thinkers (1978), Concepts and Categories: Philosophical Essays (1978), Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas (1979), Personal Impressions (1980), The Crooked Timber of Humanity: Chapters in the History of Ideas (1990), The Sense of Reality: Studies in Ideas and their History (1996) and The Proper Study of Mankind: An Anthology of Essays (1997).

Isaiah Berlin died at the Acland Nursing Home, 25 Banbury Road, Oxford, on 5 November 1997.

On this day in 1944 Allied landings in Normandy. According to Charles Messenger, the author of The D-Day Atlas: Anatomy of the Normandy Campaign (2004): "The first D-Day actions by the Allies were a series of airbourne deception operations mounted by the RAF. Almost as soon as dusk had fallen on 5th June, Lancaster bombers of 617 Squadron, the Dambusters, were overflying the Straight of Dover in a precise elliptical course, dropping strips of aluminum foil known as Window. Below them sixteen small ships towed balloons fitted with reflectors. The idea was to present to the German coastal radars a picture of a convoy crossing towards the Pas-de-Calais. Stirlings of 218 Squadron were carrying out a similar exercise off Boulogne, while other Stirlings and Halifaxes dropped dummy parachutes and various devices to represent rifle fire in order to simulate airborne landings well to the south of the drop zones of the two US airborne divisions."

David Woodward, a journalist with the Manchester Guardian, took part in the operation: "It was nearly dark when they formed up to enter the planes, and by torchlight the officers read to their men the messages of good wishes from General Eisenhower and General Montgomery. Then from this aerodrome and from aerodromes all over the country an armada of troop-carrying 'planes protected by fighters and followed by more troops aboard gliders took the air. The weather was not ideal for an airborne operation, but it was nevertheless decided to carry it out. The Germans would be less likely to be on their guard on a night when the weather was unfavourable for an attack. First came parachutists, whose duty it was to destroy as far as possible the enemy's defences against an air landing. Then came the gliders with the troops to seize various points, and finally more gliders carrying equipment and weapons of all kinds. Out of the entire force of 'plane which took the unit into action only one tug and one glider were shot down."

The Allies also sent in three airborne divisions, two American and one British, to prepare for the main assault by taking certain strategic points and by disrupting German communications. The first to land, at 1.30 a.m. on 6th June was the 101st Airbourne Division. Its task was to drop two miles behind Utah beach and secure the causeways leading to it. The landings were very scattered. Some men were ten miles away from their intended target. They valso had the problem of orientating themselves in the darkness. To help them identifying one another, each man had been issued with a small metal object, which when pressed made a noise like a cricket. Unfortunately, some of these fell into German hands and were used to trap the paratroopers.

Guy Remington was one of those parachuted into France on 6th June, 1944. "The green light flashed and at seven minutes past midnight. The jump master shouted, 'Go!' I was the second man out. The black Normandy pastures tilted and turned far beneath me. The first German flare came arching up, and instantly machine-guns and forty-millimetre guns began firing from the corners of the fields, stripping the night with yellow, green, blue, and red tracers. Fire licked through the sky and blazed around the transports heaving high overhead. I saw some of them go plunging down in flames. One of them came down with a trooper, whose parachute had become caught on the tailpiece, streaming out behind. I heard a loud gush of air: a man went hurtling past, only a few yards away, his parachute collapsed and burning. Other parachutes, with men whose legs had been shot off slumped in the harness, floated gently toward the earth. I was caught in a machine-gun cross-fire as I approached the ground. It seemed impossible that they could miss me. One of the guns, hidden in a building, was firing at my parachute, which was already badly torn; the other aimed at my body. I reached up, caught the left risers of my parachute, and pulled on them. I went into a fast slip, but the tracers followed me down. I held the slip until I was about twenty-five feet from the ground and then let go the risers. I landed up against a hedge in a little garden at the rear of a German barracks. There were four tracer holes through one of my pants legs, two through the other, and another bullet had ripped off both my breast pockets, but I hadn't a scratch."

Major Friedrich Hayn, a staff officer with the German Army, was in Normandy on 6th June, 1944: "At 01.11 hours - an unforgettable moment - the field telephone rang. Something important was coming through: while listening to it the General stood up stiffly, his hand gripping the edge of the table. With a nod he beckoned his chief of staff to listen in. Enemy parachute troops dropped east of the Orne estuary. This message from 716 Intelligence Service struck light lightning. Was this, at last, the invasion, the storming of fortress Europe? Someone said haltingly, 'Perhaps they are only supply troops for the French Resistance?' While the pros and cons were still being discussed, 709 Infantry Division from Valognes announced: 'Enemy parachute troops south of St Germain-de-Varreville and near Ste Marie-du-Mont. A second drop west of the main Carentan-Valognes road on both sides of the Merderet river and the Ste Mere-Eglise-Pont-l'Abbe road. Fighting for the river crossings in progress.' It was now about 01.45 hours. Three dropping zones near the front! Two were clearly at important traffic junctions. The third was designed to hold the marshy meadows at the mouth of the Dives and the bridge across the canalised Orne near Ranville. It coincided with the corps boundary, with the natural feature which formed our northern flank but would serve the same purpose for an enemy driving south."

At 4.00 a.m. the first wave of US glider-borne troops came in to land. These men carried the heavier weapons which the paratroopers would need to hold the perimeter. However, the German defences were now fully aware an invasion was taking place and they opened up a heavy fire and a number of the aircraft were shot down. An estimated three-quarters of the gliders did manage to reach the landing zones, but many of them crashed into thick hedgerows and stone walls. A large number of the jeeps and artillery guns brought in this way were lost.

2nd Lieutenant Leon E. Mendel was a member of the 325 Glider Infantry.: "My glider made a beautiful landing at Ecoqueneauville and I made my way south to my assembly point at Les Forges crossroads. Here I got the bad news that I had lost half of my six-man team in glider crashes. The good news was the others had already eight German prisoners for ininterrogation." Of the 23,000 airborne troops, 15,500 were Americans and of these, 6,000 were killed or seriously wounded.

On this day in 1944 Anne Frank writes in her diary about D-Day Invasion. "This is D-day, came the announcement over the British radio. The invasion has begun! According to the German news, British parachute troops have landed on the French coast. British landing craft are in battle with the German Navy, says the BBC. Great commotion in the 'Secret Annexe'! Would the long-awaited liberation that has been talked of so much but which still seems too wonderful, too much like a fairy-tale, ever come true? Could we be granted victory this year, 1944? We don't know yet, but hope is revived within us; it gives us fresh courage, and makes us strong again.

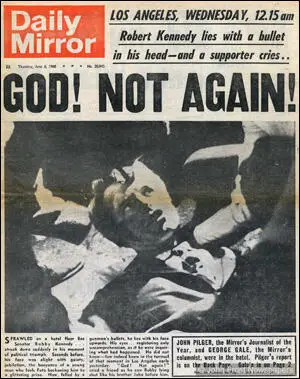

On this day in 1968 Robert Kennedy is assassinated. Robert Kennedy won the primary in California obtaining 46.3% (Eugene McCarthy received 41.8%). On hearing the result Kennedy went down to the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel to speak to his supporters. He commented on “the divisions, the violence, the disenchantment with our society; the divisions, whether it’s between blacks and whites, between the poor and the more affluent, or between age groups or on the war in Vietnam”. Kennedy claimed that the United States was “a great country, an unselfish country and a compassionate country” and that he had the ability to get people to work together to create a better society.

Robert Kennedy now began his journey to the Colonial Room where he was to hold a press conference. Someone suggested that Kennedy should take a short cut through the kitchen. Security guard Thane Eugene Cesar took hold of Kennedy’s right elbow to escort him through the room when Sirhan Sirhan opened fire. According to Los Angeles County coroner Thomas Noguchi, who performed the autopsy, all three bullets striking Kennedy entered from the rear, in a flight path from down to up, right to left. “Moreover, powder burns around the entry wound indicated that the fatal bullet was fired at less than one inch from the head and no more than two or three inches behind the right ear.”

An eyewitness, Donald Schulman, went on CBS News to say that Sirhan “stepped out and fired three times; the security guard hit Kennedy three times.” As Dan E. Moldea pointed out: “The autopsy showed that three bullets had struck Kennedy from the right rear side, traveling at upward angles – shots that Shiran was never in a position to fire.”

Kennedy had been shot at point-blank range from behind. Two shots entered his back and a third shot entered directly behind RFK’s right ear. None of the eyewitness claim that Sirhan Sirhan was able to fire his gun from close-range. One witness, Karl Uecker, who struggled with Shiran when he was firing his gun, provided a written statement in 1975 about what he saw: “There was a distance of at least one and one-half feet between the muzzle of Shiran’s gun and Senator Kennedy’s head. The revolver was directly in front of my nose. After Shiran’s second shot, I pushed the hand that held the revolver down, and pushed him onto the steam table. There is no way that the shots described in the autopsy could have come from Shiran’s gun. When I told this to the authorities, they told me that I was wrong. But I repeat now what I told them then: Shiran never got close enough for a point-blank shot.”

Chief of Detectives Robert Houghton asked Chief of Homicide Detectives Hugh Brown to take charge of the investigation into the death of Robert Kennedy. Code-named Special Unit Senator (SUS). Houghton told Brown to investigate the possibility that there was a link between this death and those of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King.

As William Turner has pointed out in The Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy: "Houghton assertedly gave Brown free reign in electing the personnel for SUS - with one exception. He specifically designated Manny Pena, who was put in a position to control the daily flow and direction of the investigation. And his decision on all matters was final." Lieutenant Manuel Pena was an interesting appointment. In November 1967 Pena resigned from the LAPD to work for the Agency for International Development (AID). According to the San Fernando Valley Times: "As a public safety advisor, he will train and advise foreign police forces in investigative and administrative matters. Over the next year he worked with Daniel Mitrione in Latin and South America.

Charles A. O'Brien, California's Chief Deputy Attorney General, told William Turner that AID was being used as an "ultra-secret CIA unit" that was known to insiders as the "Department of Dirty Tricks" and that it was involved in teaching foreign intelligence agents the techniques of assassination.

FBI agent Roger LaJeunesse claimed that Manuel Pena had been carrying out CIA special assignments for at least ten years. This was confirmed by Pena's brother, a high school teacher, who told television journalist, Stan Bohrman, a similar story about his CIA activities. In April 1968 Pena surprisingly resigned from AID and returned to the LAPD.

According to Dan E. Moldea (The Killing of Robert F. Kennedy), Houghton told the SUS team working on the case: "We're not going to have another Dallas here. I want you to act as if there was a conspiracy until we can prove that there wasn't one."

Lieutenant Manuel Pena argued that Sirhan Sirhan was a lone gunman. Shiran’s lead attorney, Grant Cooper, went along with this theory. As he explained to William W. Turner, “a conspiracy defence would make his client look like a contract killer”. Cooper’s main strategy was to portray his client as a lone-gunman in an attempt to spare Sirhan the death penalty by proving “diminished capacity”. Sirhan was convicted and sentenced before William W. Harper, an independent ballistics expert, proved that the bullets removed from Kennedy and newsman William Weisel, were fired from two different guns.

After Harper published his report, Joseph P. Busch, the Los Angeles District Attorney, announced he would look into the matter. Thane Eugene Cesar was interviewed and he admitted he pulled a gun but insisted it was a Rohm .38, not a .22 (the caliber of the bullets found in Kennedy). He also claimed that he got knocked down after the first shot and did not get the opportunity to fire his gun. The LAPD decided to believe Cesar rather than Donald Schulman, Karl Uecker and William W. Harper and the case was closed.

Cesar admitted that he did own a .22 H & R pistol. However, he claimed that he had sold the gun before the assassination to a man named Jim Yoder. William W. Turner tracked down Yoder in October, 1972. He still had the receipt for the H & R pistol. It was dated 6 th September, 1968. Cesar therefore sold the pistol to Yoder three months after the assassination of Robert Kennedy.

Cesar had been employed by Ace Guard Service to protect Robert Kennedy at the Ambassador Hotel. This was not his full-time job. During the day he worked at the Lockheed Aircraft plant in Burbank. According to Lisa Pease, Cesar had formerly worked at the Hughes Aircraft Corporation. Lockheed and Hughes were two key companies in the Military-Industrial-Congressional Intelligence Complex.

Thane Eugene Cesar was a Cuban American who had registered to vote for George Wallace’s American Independent Party. Jim Yoder claimed that Cesar appeared to have no specific job at Lockheed and had “floating” assignments and often worked in off-limits areas which only special personnel had access to. According to Yoder, these areas were under the control of the CIA.

Yoder also gave Turner and Christian details about the selling of the gun. Although he did not mention the assassination of Robert Kennedy he did say “something about going to the assistance of an officer and firing his gun.” He added that “there might be a little problem over that.”

Cesar was afraid that the assassination had been captured on film. It was. Scott Enyart, a high-school student, was taking photographs of Robert Kennedy as he was walking from the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel to the Colonial Room where the press conference was due to take place. Enyart was standing slightly behind Kennedy when the shooting began and snapped as fast as he could. As Enyart was leaving the pantry, two LAPD officers accosted him at gunpoint and seized his film. Later, he was told by Detective Dudley Varney that the photographs were needed as evidence in the Sirhan trial. The photographs were not presented as evidence but the court ordered that all evidential materials had to be sealed for twenty years.

In 1988 Scott Enyart requested that his photographs should be returned. At first the State Archives claimed they could not find them and that they must have been destroyed by mistake. Enyart filed a lawsuit which finally came to trial in 1996. During the trial the Los Angeles city attorney announced that the photos had been found in its Sacramento office and would be brought to the courthouse by the courier retained by the State Archives. The following day it was announced that the courier’s briefcase, that contained the photographs, had been stolen from the car he rented at the airport. The photographs have never been recovered and the jury subsequently awarded Scott Enyart $450,000 in damages.

One possible connection between the deaths of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy is that they were all involved in a campaign to bring an end to the Vietnam War. One man who does believe there is a connection is Edward Kennedy. NBC television correspondent Sander Vanocur, travelled with Edward Kennedy on the aircraft that brought back his Robert’s body to New York. Vanocur reported Kennedy as saying that “faceless men” (Lee Harvey Oswald, James Earl Ray and Sirhan Sirhan) had been charged with the killing of his brothers and Martin Luther King. Kennedy added: “Always faceless men with no apparent motive. There has to be more to it.”

Lieutenant Manuel Pena remained convinced that Sirhan Sirhan was a lone-gunman. He told Marilyn Barrett in an interview on 12th September, 1992: "Sirhan was a self-appointed assassin. He decided that Bobby Kennedy was no good, because he was helping the Jews. And he is going to kill him." He also added: "I did not come back (to the LAPD) as a sneak to be planted. The way they have written it, it sounds like I was brought back and put into the (Kennedy) case as a plant by the CIA, so that I could steer something around to a point where no one would discover a conspiracy. That's not so."