The United States and the First World War

At the beginning of the 20th century the United States was the most powerful country in the world. The world leader in coal and steel production, the USA was also a major producer of raw materials. The most important of these being wheat, cotton and oil, which accounted for more than a third of all the USA's exports. With a population of over 100,000,000, the USA had the potential to decide the outcome of the First World War. However, in 1914, the country had no overseas alliances and on 19th August, President Woodrow Wilson declared a policy of strict neutrality. He argued "the true spirit of neutrality... is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned." (1)

Although the USA had strong ties with Britain, Wilson was concerned about the large number of people in the country who had been born in Germany and Austria. Other influential political leaders argued strongly in favour of the USA maintaining its isolationist policy. This included the pacifist pressure group, the American Union Against Militarism, led by Lillian Wald and Crystal Eastman. (2)

Some people in the USA argued that they should expand the size of its armed forces in case of war. General Leonard Wood, the former US Army Chief of Staff, formed the National Security League in December, 1914. Wood and his organization called for universal military training and the introduction of conscription as a means of increasing the size of the US Army. He was supported by former secretaries of war Elihu Root and Henry Stimson. The former president, Theodore Roosevelt, was probably Wilson greatest critic and angrily denounced his neutral foreign policy as a violation of American rights." (3)

On 4th February, 1915, Admiral Hugo Von Pohl, sent an order to senior figures in the German Navy: "The waters round Great Britain and Ireland, including the English Channel, are hereby proclaimed a war region. On and after February 18th, every enemy merchant vessel found in this region will be destroyed, without its always being possible to warn the crews or passengers of the dangers threatening. Neutral ships will also incur danger in the war region, where, in view of the misuse of neutral flags ordered by the British Government, and incidents inevitable in sea warfare, attacks intended for hostile ships may affect neutral ships also." (4)

Soon afterwards the German government announced an unrestricted warfare campaign. This meant that any ship taking goods to Allied countries was in danger of being attacked. This broke international agreements that stated commanders who suspected that a non-military vessel was carrying war materials, had to stop and search it, rather than do anything that would endanger the lives of the occupants.

This message was reinforced when the German Embassy issued a statement on its new policy: "Travellers intending to embark for an Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that in accordance with the formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or any of her allies are liable to destruction in those waters; and that travellers sailing in the war zone in ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk." (5)

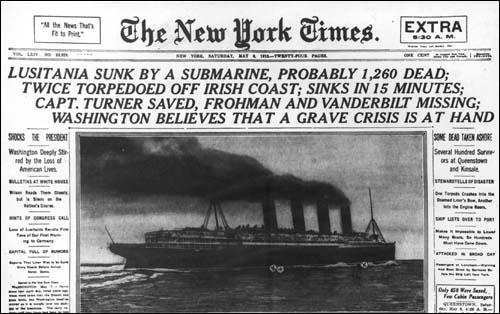

Sinking of the Lusitania

The Lusitania, was at 32,000 tons, the largest passenger vessel on transatlantic service, left New York harbour for Liverpool on 1st May, 1915. It was 750ft long, weighed 32,500 tons and was capable of 26 knots. On this journey the ship carried 1,257 passengers and 650 crew. Most of the passengers were aware of the risks they were taking because of the statements on unrestricted warfare by the German government.

Margaret Haig Thomas, was the daughter of David Alfred Thomas, who had been sent by David Lloyd George to the United States to arrange the supply of munitions for the British armed forces. Margaret later recalled that in New York City during the weeks preceding the voyage "there was much gossip of submarines". It was "stated and generally believed that a special effort was to be made to sink the great Cunarder so as to inspire the world with terror". On the morning that the Lusitania set sail the warning that had been issued by the German Embassy on 22nd April 1915, was "printed in the New York morning papers directly under the notice of the sailing of the Lusitania". Margaret commented that "I believe that no British and scarcely any American passengers acted on the warning, but we were most of us very fully conscious of the risk we were running." (6)

At 1.20pm on 7th May 1915, the U-20, only ten miles from the coast of Ireland, surfaced to recharge her batteries. Soon afterwards Captain Walther Schwieger, the commander of the German U-Boat, observed the Lusitania in the distance. Schwieger gave the order to advance on the liner. The U20 had been at sea for seven days and had already sunk two liners and only had two torpedoes left. He fired the first one from a distance of 700 metres. Watching through his periscope it soon became clear that the Lusitania was going down and so he decided against using his second torpedo.

William McMillan Adams was travelling with his father. "I was in the lounge on A Deck when suddenly the ship shook from stem to stem, and immediately started to list to starboard. I rushed out into the companionway. While standing there, a second, and much greater explosion occurred. At first I thought the mast had fallen down. This was followed by the falling on the deck of the water spout that had been made by the impact of the torpedo with the ship. My father came up and took me by the arm. We went to the port side and started to help in the launching of the lifeboats."

Adams soon discovered that there was a major problem with the lifeboats: "Owing to the list of the ship, the lifeboats had a tendency to swing inwards across the deck and before they could be launched, it was necessary to push them over the side of the ship... It was impossible to lower the lifeboats safely at the speed at which the Lusitania was still going. I saw only two boats launched from this side. The first boat to be launched, for the most part full of women, fell sixty or seventy feet into the water, all the occupants being drowned. This was owing to the fact that the crew could not work the davits and falls properly, so let them slip out of their hands, and sent the lifeboats to destruction." (7)

Margaret Haig Thomas was also unable to get into a lifeboat: "It became impossible to lower any more from our side owing to the list on the ship. No one else except that white-faced stream seemed to lose control. A number of people were moving about the deck, gently and vaguely. They reminded one of a swarm of bees who do not know where the queen has gone. I unhooked my skirt so that it should come straight off and not impede me in the water. The list on the ship soon got worse again, and, indeed, became very bad. Presently the doctor said he thought we had better jump into the sea. I followed him, feeling frightened at the idea of jumping so far (it was, I believe, some sixty feet normally from A deck to the sea), and telling myself how ridiculous I was to have physical fear of the jump when we stood in such grave danger as we did. I think others must have had the same fear, for a little crowd stood hesitating on the brink and kept me back. And then, suddenly, I saw that the water had come over on to the deck. We were not, as I had thought, sixty feet above the sea; we were already under the sea. I saw the water green just about up to my knees. I do not remember its coming up further; that must all have happened in a second. The ship sank and I was sucked right down with her." (8)

War Propaganda

Of the 2,000 passengers on board, 1,198 were drowned, among them 128 Americans. (9) The German newspaper Die Kölnische Volkszeitung supported the decision to sink the Lusitania: "The sinking of the giant English steamship in a success of moral significance which is still greater than material success. With joyful pride we contemplate this latest deed of our Navy. It will not be the last. The English wish to abandon the German people to death by starvation. We are more humane. we simply sank an English ship with passengers, who, at their own risk and responsibility, entered the zone of operations." (10)

The German foreign secretary, Gottlieb von Jagow, issued a statement where he attempted to defend the sinking of the Lusitania. "The Imperial Government must specially point out that on her last trip the Lusitania, as on earlier occasions, had Canadian troops and munitions on board, including no less than 5,400 cases of ammunition destined for the destruction of brave German soldiers who are fulfilling with self-sacrifice and devotion their duty in the service of the Fatherland. The German Government believes that it acts in just self-defense when it seeks to protect the lives of its soldiers by destroying ammunition destined for the enemy with the means of war at its command." (11)

The sinking of the Lusitania had a profound impact on public opinion in the United States. The German government apologized for the incident, but claimed its U-boat only fired one torpedo and the second explosion was a result of a secret cargo of heavy munitions on the ship. If this was true, Britain was guilty of breaking the rules of warfare by using a civilian ship to carry ammunition. British authorities rejected this charge and claimed that the second explosion was caused by coal dust igniting in the ship's almost empty bunkers.

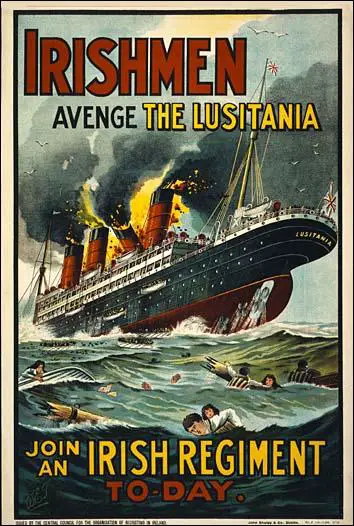

Some newspapers in the United States called on President Woodrow Wilson to declare war on Germany. However, he refused to do this as he wanted "to preserve the world's respect by abstaining from any course of action likely to awaken the hostility of either side in the war, and so to keep the United States free to undertake the part of peacemaker". (12) However, when it became clear that he intended to keep out of the First World War for economic reasons. (13) The British government decided to use the sinking of the Lusitania to recruit men into the armed forces and published several posters in 1915.

Since the sinking of the Lusitania there has been great debate about the morality of the unrestricted warfare campaign. Howard Zinn, the author of A People's History of the United States (1980), has argued that it was not a German atrocity: "It was unrealistic to expect that the Germans should treat the United States as neutral in the war when the U.S. had been shipping great amounts of war materials to Germany's enemies... The United States claimed the Lusitania carried an innocent cargo, and therefore the torpedoing was a monstrous German atrocity. Actually, the Lusitania was heavily armed: it carried 1,248 cases of 3-inch shells, 4,927 boxes of cartridges (1,000 rounds in each box), and 2,000 more cases of small-arms ammunition. Her manifests were falsified to hide this fact, and the British and American governments lied about the cargo." (14)

Gregg Bemis, a retired venture capitalist, purchased the Lusitania. He was interviewed about this in 2002 and he explained why he believed that the ship carried munitions. "The fact is that the ship sank in 18 minutes. That could only happen as the result of a massive second explosion. We know there was such an explosion, and the only thing capable of doing that is ammunitions. It's virtually impossible to get coal dust and damp air in the right mixture to explode, and none of the crew who were working in the boiler rooms and survived say anything about a boiler exploding. " (15)

In 2014 a government document was published that indicated that Zinn and Bernis were right that the ship was used to transport munitions. In 1982 it was announced that attempts would be made to salvage the ship. This created panic in Whitehall. Noel Marshall, the head of the Foreign Office's North America department, admitted on 30th July 1982: "Successive British governments have always maintained that there was no munitions on board the Lusitania (and that the Germans were therefore in the wrong to claim to the contrary as an excuse for sinking the ship). The facts are that there is a large amount of ammunition in the wreck, some of which is highly dangerous. The Treasury have decided that they must inform the salvage company of this fact in the interests of the safety of all concerned. Although there have been rumours in the press that the previous denial of the presence of munitions was untrue, this would be the first acknowledgement of the facts by HMG." (16)

The Zimmermann Telegram

The war helped the USA economy with exported goods to Allied countries increasing from $825 million in 1914 to $3.2 billion in 1916. This made it possible for Britain and France to keep fighting the war against the Central Powers and this influenced Germany's decision to announce its unrestricted submarine warfare policy. Opinion against Germany hardened after the sinking of the Lusitania. William Jennings Bryan, the pacifist Secretary of State, resigned and was replaced by the pro-Allied Robert Lansing. Wilson announced an increase in the size of the US armed forces.

However, in the 1916 Presidential election campaign, Woodrow Wilson stressed his policy of neutrality and his team used the slogan: "He kept us out of the war". However, he did make a speech after his victory he warned Germany that submarine warfare resulting in American deaths would not be tolerated, saying: "The nation that violates these essential rights must expect to be checked and called to account by direct challenge and resistance. It at once makes the quarrel in part our own." (17)

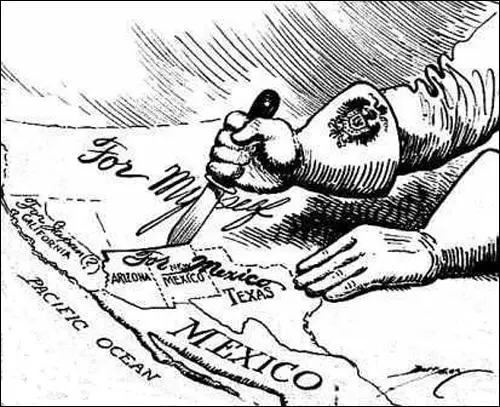

On 16th January 1917, the German Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a coded telegram to the ambassador in Mexico City where he informed him that Germany intended to begin unrestricted submarine warfare on 1st February. He also instructed the ambassador to propose an alliance with Mexico if war broke out between Germany and the United States. In return, the telegram proposed that Germany and Japan would help Mexico regain the territories that it lost to the United States in 1848 (Texas, New Mexico and Arizona). (18)

On the outbreak of the First World War the Admiralty established the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS). People such as Alastair Denniston, Alfred Dilwyn Knox and Frank Birch were involved in intercepting, decrypting, and interpreting naval staff German and other enemy wireless and cable communications. GCCS obtained a copy of the Zimmermann Telegram and after it was decrypted it was passed to the American government. (19)

United States enters the War

When he received details of the telegram, President Woodrow Wilson did not immediately declare war and instead commented, "We are the sincere friends of the German people and earnestly desire to remain at peace with them. We shall not believe they are hostile to us unless or until we are obliged to believe it". (20)

On 21st March the United States tanker, The Healdton, was sunk by a German submarine while in a specially declared "safety zone" in Dutch waters. Twenty American crewmen were killed. Wilson called a meeting with his Cabinet and it unanimously decided to go to war. On 2nd April, President Wilson asked for permission to go to war. This was approved in the Senate on 4th April by 82 votes to 6, and two days later, in the House of Representatives, by 373 to 50. Still avoiding alliances, war was declared against the German government (rather than its subjects). (21)

Germany was confident that they could bring Britain to collapse before American action became effective. As A. J. P. Taylor pointed out: "They nearly succeeded. The number of ships sunk by U-boats rose catastrophically. In April 1917 one ship out of four leaving British ports never returned. That month nearly a million tons of shipping were sunk, two thirds of it British. New building could replace only one ton in ten. Neutral ships refused cargoes for British ports. The British reserve of wheat dwindled to six weeks' supply." (22)

When the USA declared war in April 1917, Wilson sent the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) under the command of General John Pershing to the Western Front. The Selective Service Act, drafted by Brigadier General Hugh Johnson, was quickly passed by Congress. The law authorized President Wilson to raise a volunteer infantry force of not more than four divisions. Pershing arrived in France in June 1917, with his troops and initially stated that they were at the disposal of General Ferdinand Foch. "It was an inspiring gesture - although in practice he continued to keep a tight hold on his troops and, with rare exceptions, only allowed them to take over parts of the front as complete divisions." (23)

The Development of Tanks

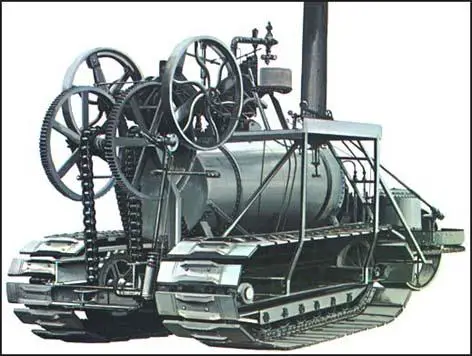

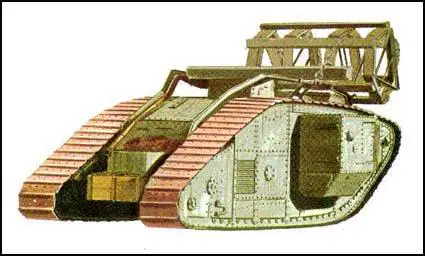

The idea of an armoured tracked vehicle that would provide protection from machines gun fire was first discussed by army officers in 1914. Two of the officers, Colonel Ernest Swinton and Colonel Maurice Hankey, both became convinced that it was possible to develop a fighting vehicle that could play an important role in any future war. On the outbreak of the First World War Colonel Swinton was sent to the Western Front to write reports on the war. After observing early battles where machine-gunners were able to kill thousands of infantryman advancing towards enemy trenches, Swinton wrote that "petrol tractors on the caterpillar principle and armoured with hardened steel plates" would be able to counteract the machine-gunner. (24)

To maintain secrecy, Swinton coined the euphemism "tank", to describe the new weapon. However, he faced real problems from his boss, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State of War. His style of leadership was very authoritarian and was reluctant to experiment. Swinton later argued that after putting the idea to Kitchener without getting any support he hesitated to press too hard because he dreaded a direct order to drop it. (25)

Richard Hornsby & Sons also worked on the project and eventually produced the Killen-Strait Armoured Tractor. The tracks consisted of a continuous series of steel links, joined together with steel pins. In June 1915 the Killen-Strait was tested out in front of Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George at Wormwood Scrubs. The machine successfully cut through barbed wire entanglements. Churchill became convinced that this new machine would enable trenches to be crossed quite easily. (26)

Colonel Ernest Swinton persuaded the newly-formed Inventions Committee to spend money on the development of a small land-ship. and drew up specifications for this new machine. This included: (i) a top speed of 4 mph on flat ground; (ii) the capability of a sharp turn at top speed; (iii) a reversing capability; (iv) the ability to climb a 5-foot earth parapet; (v) the ability to cross a 8-foot gap; (vi) a vehicle that could house ten crew, two machine guns and a 2-pound gun. Winston Churchill wrote to H. H. Asquith, the prime minister about Swinton's ideas. (27)

In February 1915, Churchill arranged for the Admiralty to spend £70,000 on building an experimental "land ship" (Swinton insisted on calling them tanks). A month later Churchill agreed that eighteen prototypes should be built (six were to have wheels and twelve tracks). However, most of the major work was undertaken by the War Office and Ministry of Munitions. (28)

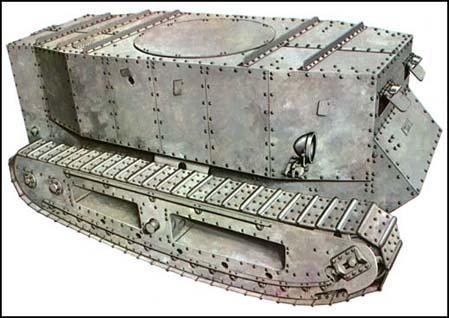

The first tank developed was given the nickname Little Willie. This prototype tank with its Daimler engine, had track frames 12 feet long, weighed 14 tons and could carry a crew of three, at speeds of just over three miles. The speed dropped to less than 2 mph over rough ground and most importantly of all, was unable to cross broad trenches. Although the performance was disappointing, Colonel Swinton remained convinced that when modified, the tank would enable the Allies to defeat the Central Powers. (29)

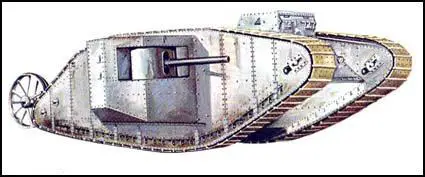

The production of Little Willie by Lieutenant Walter G. Wilson and William Tritton in the late summer of 1915 revealled several technical problems. The two men immediately began work on an improved tank. Mark I, nicknamed Mother, was much longer than the first tank they made. This kept the centre of gravity low and the extra length helped the tank grip the ground. Sponsons were also fitted to the sides to accommodate two naval 6-pound guns. In trials carried out in January 1916 the tank crossed a 9ft. wide trench with a 6ft. 6in. parapet and convinced watchers of its "obstacle-crossing ability". (30)

it was decided to demonstrate the new tank to Britain's political and military leaders. Under conditions of great secrecy, Lord Kitchener, Secretary of State of War, David Lloyd George, Minister of Munitions, and Reginald McKenna, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, were invited to Hatfield Park on 2nd February, 1916 to see Mark I in action. Lord Kitchener was unimpressed describing tanks as "mechanical toys" and asserting that "the war would never be won by such machines". Although without military experience, Lloyd George and McKenna saw their potential and placed an order for a 100 tanks. (31)

According to Colonel Charles Repington, that the government's greatest advocate of tanks, Winston Churchill, "wanted them to wait until there were something like a thousand Tanks, and then to win a great battle with them as a surprise". (32) This was acceptable to Sir Douglas Haig, Commander-in Chief of the British Army, as he had doubts about the value of tanks. However, after failing to break through German lines at the Battle of the Somme, Haig gave orders that tanks that had reached the Western Front, should be used at Flers-Coucelette on 15th July, 1916. (33)

It was not until 28th September, 1916, that the newspapers were allowed to report the use of tanks on the Western Front in France. The Manchester Guardian reported: "The British army has struck the enemy another heavy blow north of the Somme... Armoured cars (tanks) working with the infantry were the great surprise of this attack. Sinister, formidable, and industrious, these novel machines pushed boldly into No Man's Land, astonishing our soldiers no less than they frightened the enemy." (34)

The Daily Chronicle also carried news of tanks that day. "Over our own trenches in the twilight of the dawn those motor-monsters had lurched up, and now it came crawling forward to the rescue, cheered by the assaulting troops, who called out words of encouragement to it and laughed, so that some men were laughing even when bullets caught them in the throat. 'Creme de Menthe' was the name given to this particular creature, and it waddled forward right over the old German trenches. There was a whip of silence from the enemy. Then, suddenly, their machine-gun fire burst out in nervous spasms and splashed the sides of 'Creme de Menthe'. But the tank did not mind. The bullets fell from its sides harmlessly. From its sides came flashes of fire and a hose of bullets, and then it trampled around over machine emplacements 'having a grand time', as one of the men said with enthusiasm. It crushed the machine-guns under its heavy ribs, and killed machine-gun teams with deadly fire. The infantry followed in and took the place after this good help, and then advanced again round the flanks of the monster." (35)

In reality, the tanks were not a great success the first time they were used. Of the 59 tanks in France, only 49 were considered to be in good working order. Of these, 17 broke down on the way to their starting point at Flers. The sight of the tanks created panic and had a profound effect on the morale of the German Army. Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff of the Tank Corps, was convinced that these machines could win the war and persuaded Sir Douglas Haig to ask the government to supply him with another 1,000 tanks. Basil Liddell Hart argues the main problem was that "Swinton's memorandum laid down a number of conditions which were disregarded in September, 1916... The sector for tank attack was to be carefully chosen to comply with the powers and limitations of the tanks." (36)

Battle of Passchendaele

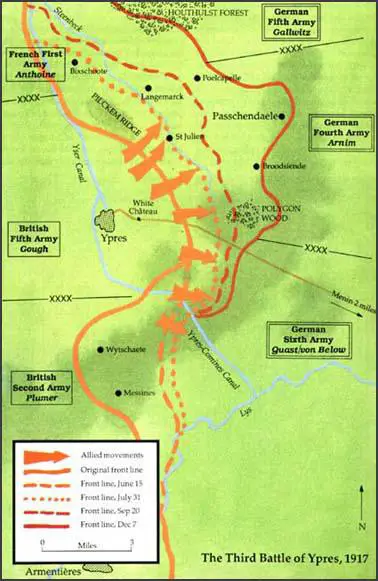

The third major battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, took place between July and November, 1917. General Haig, the British Commander in Chief in France, was encouraged by the gains made at the offensive at Messines. Haig was convinced that the German army was now close to collapse and once again made plans for a major offensive to obtain the necessary breakthrough. The official history of the battle claimed Haig's plan "may seem super-optimistic and too far-reaching, even fantastic". Many historians have suggested that the main problem was that Haig "had chosen a field of operations where the preliminary bombardment churned the Flanders plain into impassable mud." (37)

The opening attack at Passchendaele was carried out by General Hubert Gough and the British Fifth Army with General Herbert Plumer and the Second Army joining in on the right and General Francois Anthoine and the French First Army on the left. After a 10 day preliminary bombardment, with 3,000 guns firing 4.25 million shells, the British offensive started at Ypres a 3.50 am on 31st July.

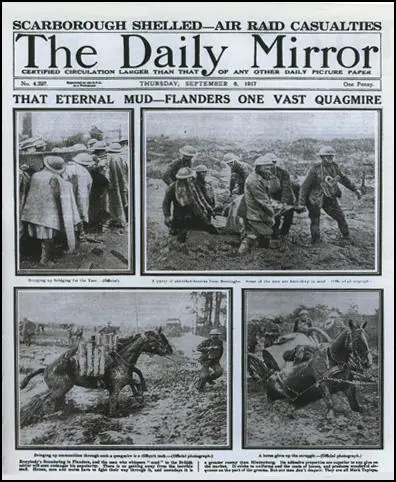

Allied attacks on the German front-line continued despite very heavy rain that turned the Ypres lowlands into a swamp. The situation was made worse by the fact that the British heavy bombardment had destroyed the drainage system in the area. This heavy mud created terrible problems for the infantry and the use of tanks became impossible. Percival Phillips of The Daily Express commented: "The weather changed for the worse last night, although fortunately too late to hamper the execution of our plans. The rain was heavy and constant throughout the night. It was still beating down steadily when the day broke chill and cheerless, with a thick blanket of mist completely shutting off the battlefield. During the morning it slackened to a dismal drizzle, but by this time the roads, fields, and footways were covered with semi-liquid mud, and the torn ground beyond Ypres had become in places a horrible quagmire." (38)

As William Beach Thomas, a journalist working for the Daily Mail, pointed out: "Floods of rain and a blanket of mist have doused and cloaked the whole of the Flanders plain. The newest shell-holes, already half-filled with soakage, are now flooded to the brim. The rain has so fouled this low, stoneless ground, spoiled of all natural drainage by shell-fire, that we experienced the double value of the early work, for today moving heavy material was extremely difficult and the men could scarcely walk in full equipment, much less dig. Every man was soaked through and was standing or sleeping in a marsh. It was a work of energy to keep a rifle in a state fit to use." (39)

On 31st July 1917, Lieutenant Robert Sherriff and his men of the the East Surrey Regiment were called forward to attack the German positions. "The living conditions in our camp were sordid beyond belief. The cookhouse was flooded, and most of the food was uneatable. There was nothing but sodden biscuits and cold stew. The cooks tried to supply bacon for breakfast, but the men complained that it smelled like dead men.... At dawn on the morning of the attack, the battalion assembled in the mud outside the huts. I lined up my platoon and went through the necessary inspection. Some of the men looked terribly ill: grey, worn faces in the dawn, unshaved and dirty because there was no clean water. I saw the characteristic shrugging of their shoulders that I knew so well. They hadn't had their clothes off for weeks, and their shirts were full of lice." (40)

A copy of this newspaper can be obtained from Historic Newspapers.

In the first few days of fighting the Allies suffered about 35,000 killed and wounded. Haig described the situation as "highly satisfactory" and "the losses slight". David Lloyd George was furious and met with Sir William Robertson, the Chief of Staff, and complained about "the futile massacre... piled up the ghastly hecatombs of slaughter". Lloyd George repeatedly told Robertson that the offensive must be "abandoned as soon as it became evident that its aims were unattainable." (41)

The German Fourth Army held off the main British advance and restricted the British to small gains on the left of the line. Eventually, General Haig called off the attacks and did not resume the offensive until 26th September. These attacks enabled the British forces to take possession of the ridge east of Ypres. Despite the return of heavy rain, Haig ordered further attacks towards the Passchendaele Ridge. Attacks on the 9th and 12th October were unsuccessful. As well as the heavy mud, the advancing British soldiers had to endure mustard gas attacks. This gas caused particular problems, because its odour was not very strong. (42)

Three more attacks took place in October and on the 6th November the village of Passchendaele was finally taken by British and Canadian infantry. Sir Douglas Haig was severely criticized for continuing with the attacks long after the operation had lost any real strategic value. Since the beginning of the offensive, British troops had advanced five miles at a cost of at least 250,000 casualties, though some authorities say 300,000. "Certainly 100,000 of them occurred after Haig's insistence on continuing the fighting into October. German losses over the whole of the Western Front for the same period were about 175,000." (43)

Battle of Cambrai

After the failure of British tanks in the thick mud at Passchendaele, Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff to the Tank Corps, suggested a massed raid on dry ground between the Canal du Nord and the St Quentin Canal. General Sir Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, accepted Fuller's plan, although it was originally vetoed by the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig. However, he changed his mind and decided to launch the Cambrai Offensive. (44)

Brigadier-General John Charteris, the Chief Intelligence Officer at GHQ was involved in the planning of the offensive at Cambrai in November 1917. Lieutenant James Marshall-Cornwall discovered captured documents that three German divisions from the Russian front had arrived to strengthen the Cambrai sector. Charteris told Marshall-Cornwall: "This is a bluff put up by the Germans to deceive us. I am sure the units are still on the Russian front... If the commander in chief were to think that the Germans had reinforced this sector, it might shake his confidence in our success." (45)

Haig, who was not given this information, ordered a massed tank attack at Artois. Launched at dawn on 20th November, without preliminary bombardment, the attack completely surprised the German Army defending that part of the Western Front. Employing 476 tanks, six infantry and two cavalry divisions, the British Third Army gained over 6km in the first day. It was claimed that the use of tanks in the battle was very effective. "Tanks and cavalry co-operated in this attack, and the tanks were a most powerful aid, and cruised round and through the village, where they put out nests of machine-guns." (46)

However, Philip Gibbs of the Daily Chronicle claimed that tanks were still encountering problems: "We thought these tanks were going to win the war, and certainly they helped to do so, but there were too few of them, and the secret was let out before they were produced in large numbers. Nor were they so invulnerable as we had believed. A direct hit from a field gun would knock them out, and in our battle for Cambrai in November of 1917 I saw many of them destroyed and burnt out." (47)

Progress towards Cambrai continued over the next few days but on the 30th November, 1917, twenty-nine German divisions launched a counter-offensive. This included the use of mustard gas. One of the nurses, Vera Brittain, explained to her mother about the impact of these attacks. "We have heaps of gassed cases at present : there are 10 in this ward alone. I wish those people who write so glibly about this being a holy war, and the orators who talk so much about going on no matter how long the war lasts and what it may mean, could see a case - to say nothing of 10 cases of mustard gas in its early stages - could see the poor things all burnt and blistered all over with great suppurating blisters, with blind eyes - sometimes temporally, some times permanently - all sticky and stuck together, and always fighting for breath, their voices a whisper, saying their throats are closing and they know they are going to choke." (48)

By the time that fighting came to an end on 7th December, 1917, German forces had regained almost all the ground it lost at the start of the Cambrai Offensive. During the two weeks of fighting, the British suffered 45,000 casualties. Although it is estimated that the Germans lost 50,000 men, Sir Douglas Haig considered the offensive as a failure and reinforced his doubts about the ability of tanks to win the war. (49)

The First World War: 1918

On 8th January, 1918, President Woodrow Wilson presented his Peace Programme to Congress. Compiled by a group of US foreign policy experts, the programme included fourteen different points. The first five points dealt with general principles: Point 1 renounced secret treaties; Point 2 dealt with freedom of the seas; Point 3 called for the removal of worldwide trade barriers; Point 4 advocated arms reductions and Point 5 suggested the international arbitration of all colonial disputes. (50)

Points 6 to 13 were concerned with specific territorial problems, including claims made by Russia, France and Italy. This part of Wilson's programme also raised issues such as the control of the Dardanelles and the claims for independence by the people living in areas controlled by the Central Powers. All the major countries involved in the First World War objected to certain points in Wilson's Peace Programme but it was hoped that they would serve as the basis of peace negotiations. (51)

After the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty with the new Bolshevik government, Germany was able to withdraw its troops from the Eastern Front. It was decided to use these troops to support a massive offensive on the Western Front. The Central Powers hoped that the 1918 Spring Offensive would enable them to end the war before the United States Army became firmly established in France.

It was decided to attack Allied forces at three points along the Western Front: Arras, Lys and Aisne. British soldiers became disillusioned when all the land captured during the offensive at Passchendaele. At first the German Army had considerable success and came close to making a decisive breakthrough. However, Allied forces managed to halt the German advance at the Marne in June, 1918. (52)

By July 1918 there were over a million US soldiers in France, with around another 4,000,000 men based in America. There was also about 200,000 Afro-American soldiers in Europe. Completely segregated, they fought with the French Army during the war. General Ferdinand Foch was now able to organize a counterattack that made full use of the new troops. This included 24 divisions of the French Army, and soldiers from the United States, Britain and Italy. On 20th July the Germans began to withdraw. By the 3rd August they were back to where they were when they started the Spring Offensive in March.

Allied casualties during the 2nd Battle of the Marne were heavy: French (95,000), British (13,000) and United States (12,000). The Allies also captured 609 German officers and 26,413 enlisted men, 612 enemy artillery pieces and 3,300 machine guns. It is estimated that the German Army suffered an estimated 168,000 casualties and marked the last real attempt by the Central Powers to win the First World War. (53)

The Allied Supreme Commander, Ferdinand Foch now ordered a counter-offensive. Foch put British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig in overall charge of the offensive and he selected General Sir Henry Rawlinson and the British Fourth Army to lead the attack. The Amiens offensive took place on 8th August 1918. Every available tank was moved to Rawlinson's sector. This included 72 Whippet and 342 Mark V tanks. Rawlinson also had 2,070 artillery pieces and 800 aircraft. The German sector chosen was defended by 20,000 soldiers and were outnumbered 6 to 1 by the attacking troops. The tanks followed by soldiers met little resistance and by mid morning allied forces had advanced 12km. The Amiens line was taken, and later, General Erich Ludendorff, the man in overall charge of German military operations, described the 8th August as "the black day of the German Army in the history of the war". (54)

The Armistice

The German government of Max von Baden asked President Woodrow Wilson for a ceasefire on 4th October, 1918. "It was made clear by both the Germans and Austrians that this was not a surrender, not even an offer of armistice terms, but an attempt to end the war without any preconditions that might be harmful to Germany or Austria." This was rejected and the fighting continued. On 6th October, it was announced that Karl Liebknecht, who was still in prison, demanded an end to the monarchy and the setting up of Soviets in Germany. (55)

Although defeat looked certain, Admiral Franz von Hipper and Admiral Reinhard Scheer began plans to dispatch the Imperial Fleet for a last battle against the Royal Navy in the southern North Sea. The two admirals sought to lead this military action on their own initiative, without authorization. They hoped to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to achieve a better bargaining position for Germany regardless of the cost to the navy. Hipper wrote "As to a battle for the honor of the fleet in this war, even if it were a death battle, it would be the foundation for a new German fleet...such a fleet would be out of the question in the event of a dishonorable peace." (56)

The naval order of 24th October 1918, and the preparations to sail triggered a mutiny among the affected sailors. By the evening of 4th November, Kiel was firmly in the hands of about 40,000 rebellious sailors, soldiers and workers. "News of the events in Keil soon travelled to other nearby ports. In the next 48 hours there were demonstrations and general strikes in Cuxhaven and Wilhelmshaven. Workers' and sailors' councils were elected and held effective power." (57)

By the 8th November, workers councils took power in virtually every major town and city in Germany. This included Bremen, Cologne, Munich, Rostock, Leipzig, Dresden, Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Nuremberg. Theodor Wolff, writing in the Berliner Tageblatt: "News is coming in from all over the country of the progress of the revolution. All the people who made such a show of their loyalty to the Kaiser are lying low. Not one is moving a finger in defence of the monarchy. Everywhere soldiers are quitting the barracks." (58)

The German Social Democratic Party (SDP) in the Reichstag demanded the resignation of Kaiser Wilhem II. When that was refused, they resigned from the Reichstag and called for a general strike throughout Germany. In Munich, Kurt Eisner, the leader of the Independent Socialist Party, declared the establishment of the Bavarian Soviet Republic.

Konrad Heiden wrote: "On November 6, 1918, he (Kurt Eisner) was virtually unknown, with no more than a few hundred supporters, more a literary than a political figure. He was a small man with a wild grey beard, a pince-nez, and an immense black hat. On November 7 he marched through the city of Munich with his few hundred men, occupied parliament and proclaimed the republic. As though by enchantment, the King, the princes, the generals, and Ministers scattered to all the winds." (59)

Later that day, in order to stop the spread of the revolution, the German government agreed to surrender. On 9th November, the Kaiser abdicated fled to Holland. At 5 a.m. on 11th November, 1918, signed the armistice. It came into force at 11 a.m. All territorial conquests achieved by the Central Powers had to be abandoned. The German Army also surrendered 30,000 machine-guns, 2,000 aircraft, 5,000 locomotives, 5,000 lorries and all its submarines. (60)

The journalist, Philip Gibbs, described how the men responded on the front-line at Mons. "They wore flowers in their caps and in their tunics, red and white chrysanthemums given them by the crowds of people who cheered them on their way, people who in many of these villages had been only one day liberated from the German yoke. Our men marched singing, with a smiling light in the eyes. They had done their job, and it was finished with the greatest victory in the world." (61)

Charles Montague described how the men responded to the end of war: "The day after the fighting ended I met hundreds of men who had been prisoners and broken out just before the armistice. They were coming back into our lines, almost starving, and some of them had died of hunger and exhaustion on the way; but they came along splendidly, marching in little groups under the command of the oldest soldier in each, with their horrible black uniforms as clean and neat as hard trying could make them, marching along very steady and smart and taking no notice of anybody. I thought I had never seen the British soldier to greater advantage." (62)

German soldiers understandably felt that their suffering had all been in vain. George Grosz remarked: "I thought the war would never end. And perhaps it never did, either. Peace was declared, but not all of us were drunk with joy or stricken blind. Very little changed fundamentally, except that the proud German soldier had turned into a defeated bundle of misery and the great German army had disintegrated. I was disappointed, not because we had lost the war but because our people had allowed it to go on for so many years, instead of heeding the few voices of protest against all that mass insanity and slaughter." (63)