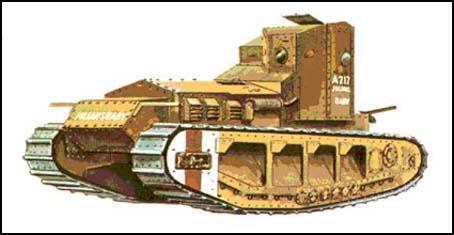

Whippet Tank

The Mark A tank, nicknamed, the Whippet, was introduced in 1917. Faster than the earlier, heavy tanks, the Whippet was intended as a cavalry style weapon. After the failure of British tanks in the thick mud at Passchendaele, Colonel John Fuller, chief of staff to the Tank Corps, suggested a massed raid on dry ground between the Canal du Nord and the St Quentin Canal. General Sir Julian Byng, commander of the Third Army, accepted Fuller's plan, although it was originally vetoed by the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig. However, he changed his mind and decided to launch the Cambrai Offensive. (1)

Haig, who was not given this information, ordered a massed tank attack at Artois. Launched at dawn on 20th November, without preliminary bombardment, the attack completely surprised the German Army defending that part of the Western Front. Employing 476 tanks (most of them Whippets), six infantry and two cavalry divisions, the British Third Army gained over 6km in the first day. It was claimed that the use of tanks in the battle was very effective. "Tanks and cavalry co-operated in this attack, and the tanks were a most powerful aid, and cruised round and through the village, where they put out nests of machine-guns." (2)

However, Philip Gibbs of the Daily Chronicle claimed that tanks were still encountering problems: "We thought these tanks were going to win the war, and certainly they helped to do so, but there were too few of them, and the secret was let out before they were produced in large numbers. Nor were they so invulnerable as we had believed. A direct hit from a field gun would knock them out, and in our battle for Cambrai in November of 1917 I saw many of them destroyed and burnt out." (3)

Progress towards Cambrai continued over the next few days but on the 30th November, 1917, twenty-nine German divisions launched a counter-offensive. This included the use of mustard gas. By the time that fighting came to an end on 7th December, 1917, German forces had regained almost all the ground it lost at the start of the Cambrai Offensive. During the two weeks of fighting, the British suffered 45,000 casualties. Although it is estimated that the Germans lost 50,000 men, Sir Douglas Haig considered the offensive as a failure and reinforced his doubts about the ability of tanks to win the war. (4)

Allied casualties during the 2nd Battle of the Marne were heavy: French (95,000), British (13,000) and United States (12,000). The Allies also captured 609 German officers and 26,413 enlisted men, 612 enemy artillery pieces and 3,300 machine guns. It is estimated that the German Army suffered an estimated 168,000 casualties and marked the last real attempt by the Central Powers to win the First World War. (5)

The Allied Supreme Commander, Ferdinand Foch now ordered a counter-offensive. Foch put British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Douglas Haig in overall charge of the offensive and he selected General Sir Henry Rawlinson and the British Fourth Army to lead the attack. The Amiens offensive took place on 8th August 1918. Every available tank was moved to Rawlinson's sector. This included 72 Whippets and 342 Mark V tanks. Rawlinson also had 2,070 artillery pieces and 800 aircraft. The German sector chosen was defended by 20,000 soldiers and were outnumbered 6 to 1 by the attacking troops. The tanks followed by soldiers met little resistance and by mid morning allied forces had advanced 12km. The Amiens line was taken, and later, General Erich Ludendorff, the man in overall charge of German military operations, described the 8th August as "the black day of the German Army in the history of the war". (6)

Primary Sources

(1) Major William Henry Lowe Watson was in charge of the 11th Company of the Tank Corps. Watson later wrote about his experiences in his book A Company of Tanks (1920)

All the tanks, except Morris's had arrived without incident at the railway embankment. Morris ditched on the bank and was a little late. Haigh and Jumbo had gone on ahead of the tanks. They crawled out beyond the embankment into No Man's Land and marked out the starting-line. It was not too pleasant a job. The enemy machine-guns were active right through the night, and the neighbourhood of the embankment was shelled intermittently.

Skinner's tank failed on the embankment. The remainder crossed it successfully and lined up for the attack just before zero. By this time the shelling had become severe. The crews waited inside their tanks, wondering if they would be hit before they started. Already they were dead-tired, for they had obtained little sleep since the long painful trek of the night before.

Suddenly our bombardment begun - it was more of a bombardment than a barrage - and the tanks crawled away into the darkness. On the extreme right Morris and Puttock were met by tremendous machine-gun fire at the wire of the Hindenburg Line. They swung to the right, as they had been ordered, and glided along in front of the wire, sweeping the parapet with their fire. Serious clutch trouble developed in Puttock's tank. It was impossible to stop since the German guns were following them.

Money's tank reached the German wire. His men must have 'missed their gears'. For less than a minute the tank was motionless, then she burst into flames. A shell had exploded the petrol tanks. A sergeant and two men escaped. Money, best of good fellows, must have been killed instantaneously by the shell.

Puttock's clutch was slipping so badly that the tank would not move, and the shells were falling ominously near. He withdrew his crew from the tank into a trench, and a moment later the tank was hit again.

Student Activities

Sinking of the Lusitania (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)