Margaret MacDonald

Margaret Ethel Gladstone was born on 20th July, 1870. Her father, John Hall Gladstone, was one of the founders of the Youth Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and was Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution. He was also a member of the Liberal Party and just before Margaret's birth had failed to win York in the 1868 General Election. Her mother, Margaret Thompson King, was closely related to the famous scientist William Thompson. Margaret's mother died soon after she was born.

Margaret Gladstone was educated at the Doreck College for Girls in Bayswater and the women's department of King's College and studied political economy under Millicent Fawcett. According to David Marquand: "Margaret was an attractive, light-hearted girl; but had all the stubborn determination, as well as the intense religious feeling of her puritan ancestors. She had no respect for middle-class convention, as she was certainly not prepared to wait meekly in her father's house till someone came to marry her." In May 1889 she became a Sunday School teacher at St. Mary Abbots Church in Kensington. She also found work as secretary of the Hoxton and Haggerston Nursing Association. In 1893 she became a volunteer worker for the Charity Organization Society in Hoxton.

Margaret's experiences of working with the poor in London resulted in her questioning the merits of capitalism. At first she was influenced by Christian Socialists, such as Frederick Denison Maurice and Charles Kingsley. After hearing Ben Tillett speak at a Unitarian Society meeting she became a socialist. She also joined the Fabian Society and in 1894 became a member of the Women's Industrial Council. Other members included Clementina Black, Eleanor Marx, Hilda Martindale, Charlotte Despard, Evelyn Sharp, Mary Macarthur, Cicely Corbett Fisher, Lily Montagu and Margery Corbett-Ashby.

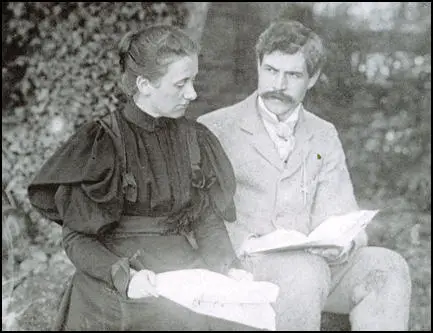

May 1895 she saw Ramsay MacDonald addressing an audience during his campaign to win the Southampton seat in the 1895 General Election. She noted that his red tie and curly hair made him look "horribly affected". However, she sent him a £1 contribution to his election fund. A few days later she became one of his campaign workers. MacDonald, along with the other twenty-seven Independent Labour Party candidates, was defeated and overall, the party won only 44,325 votes.

The following year they began meeting at the Socialist Club in St. Bride Street and at the British Museum, where they both had readers' tickets. In April 1896 she joined the ILP. In a letter she admitted that before she met him she had been terribly lonely: "But when I think how lonely you have been I want with all my heart to make up to you one tiny little bit for that. I have been lonely too - I have envied the veriest drunken tramps I have seen dragging about the streets if they were man and woman because they had each other... This is truly a love letter: I don't know when I shall show it you: it may be that I never shall. But I shall never forget that I have had the blessing of writing it."

They decided to get married and in a letter she wrote to MacDonald on 15th June, 1896 about her situation: "My financial prospects I am very hazy about, but I know I shall have a comfortable income. At present I get £80 allowance (besides board & lodging, travelling and postage); my married sister has, I think about £500 all together. When my father dies we shall each have our full share, and I suppose mine will be some hundreds a year... My ideal would be to live a simple life among the working people, spending on myself whatever seemed to keep me in best efficiency, and giving the rest to public purposes, especially Socialist propaganda of various kinds."

After they were married in 1897, Margaret MacDonald was able to finance her husband's political career from her private income. The couple travelled a great deal in the late 1890s and this gave MacDonald the opportunity to meet socialist leaders in other countries and helped him develop an good understanding of foreign affairs.

Bruce Glasier wrote: "Margaret MacDonald might easily have been taken for the nursemaid in a small middle-class family. Her naivety, simplicity, unselfishness and amazing capacity for organisation and helpful work made her one of the best liked women I have known. There was little in her to attract men, as men, but everything to attract women and men who had enthusiasm for public work." The marriage was a very happy one, and over the next few years they had six children, Alister (1898), Malcolm (1901), Ishbel (1903), David (1904), Joan (1908) and Shelia (1910).

Keir Hardie, the leader of the Independent Labour Party and George Bernard Shaw of the Fabian Society, believed that for socialists to win seats in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to form a new party made up of various left-wing groups. On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party, two from the Social Democratic Federation, one member of the Fabian Society, and seven trade unionists.

Ramsay MacDonald was chosen as the secretary of the LRC. One reason for this was Margaret's income meant that he did not have to be paid a salary. The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons.

Margaret MacDonald was active in the campaign for women's suffrage. In 1906 she helped to establish the Women's Labour League, which was established to encourage women to become involved in the Labour Party and to seek improvements in the work and family lives of working-class women. Other members included Ada Salter, Margaret Bondfield, Katherine Glasier, Charlotte Despard, Mary Gawthorpe, Mary Macarthur and Marion Phillips. MacDonald supported the non-violent Women's Freedom League as she rejected the tactics of the Women Social & Political Union.

According to David Marquand: "Although she coped efficiently with an intimidating mass of public work, there was nothing intimidating about her personality. Her clothes were the despair of her friends, and slightly shocked her much more conventional husband." Grace Paton. who worked for the MacDonalds, later recalled: "They were very untidy - he wasn't, I think he wanted to be tidy, but she never. There was a great big armchair, an enormous one full of papers; and I think she kept all the clothes she ever had, because clearing up was rather difficult."

Margaret MacDonald remained an active member of the Women's Industrial Council. According to her biographer, June Hannam: "She was secretary of the council's legal and statistical committee, and a member of its investigations and education committees.... In the early 1900s Margaret MacDonald drew attention to the needs of unemployed women. Through her efforts the central unemployment board of London appointed a special women's work committee which established municipal workrooms for clothing workers. She helped to organize a march of unemployed women in Whitehall in 1905 and in 1907 initiated a national conference on the unemployment of women dependent on their own earnings... Despite her long-standing interest in working conditions, and her own attempts to combine motherhood and public activities, she believed that women's most important role was in the home and she was consistent in her opposition to married women's paid employment."

Arthur Henderson did not have the full-support of the party and in 1910 he decided to retire as chairman. Ramsay MacDonald was expected to become the new leader but in February the family suffered two shattering emotional blows. On 3rd February his youngest son, David, died of diphtheria. Eight days later Ramsay's mother also died. It was therefore decided that George Barnes should become chairman instead. A few months later Barnes wrote to MacDonald saying he did not want the chairmanship and was "only holding the fort". He continued, "I should say it is yours anytime".

The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Two months later, on 6th February, 1911, George Barnes sent a letter to the Labour Party announcing that he intended to resign as chairman. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Arthur Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargain had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

On 4th July, 1910, Ramsay MacDonald wrote: "My little David's birthday... Sometimes I feel like a lone dog in the desert howling from pain of heart. Constantly since he died my little boy has been my companion. He comes and sits with me especially on my railway journey and I feel his little warm hand in mine. That awful morning when I was awakened by the telephone bell, and everything within me shrunk in fear for I knew I was summoned to see him die, comes back often too."

On 20th July 1911, Ramsay MacDonald arranged for Margaret MacDonald to meet William Du Bois in the House of Commons. He later explained: "A little after noon she joined me at the House of Commons with one whom she had desired to meet ever since she had read his book on the negro, Professor Du Bois; that afternoon we went to country for a weekend rest. She complained of being stiff, and jokingly showed me the finger carrying her marriage and engagement rings. It was badly swollen and discoloured, and I expressed concern. She laughed away my fears... On Saturday she was so stiff that she could not do her hair, and she was greatly amused by my attempts to help her. On Sunday she had to admit that she was ill and we returned to town. Then she took to bed."

According to Bruce Glasier she was treated by Dr. Thomas Barlow, who told MacDonald that he could not save her. "When she heard that she was doomed, she was silent, and said with a slight tremble in her voice, I am very sorry to leave you - you and the children - alone. She never wept - never to the end. She asked if the children could be brought to see her. When the boys were brought to her, she spoke to each one separately. To the boys she said, I wish you only to remember one wish of your mother's - never marry except for love."

Margaret MacDonald died on 8th September 1911, at her home, Lincoln's Inn Fields, from blood poisoning due to an internal ulcer. Her body was cremated at Golders Green on 12th September and the ashes were buried in Spynie Churchyard, a few miles from Lossiemouth. Her son, Malcolm MacDonald, later recalled: "At the time of my mother's death... my father's grief was absolutely horrifying to see. Her illness and her death had a terrible effect on him of grief; he was distracted; he was in tears a lot of time when he spoke to us... it was almost frightening to a youngster like myself."

Ramsay MacDonald wrote a short memoir of his wife, which was privately printed and circulated to friends. He told Katharine Bruce Glasier: "I felt myself hearing her approval of it, so much so that I seemed to see her hand on your shoulder as you wrote - and grew foolishly weakly blind with tears for the pain that was there."

Primary Sources

(1) Margaret Gladstone, letter to Ramsay MacDonald (15th June, 1896)

My financial prospects I am very hazy about, but I know I shall have a comfortable income. At present I get £80 allowance (besides board & lodging, travelling and postage); my married sister has, I think about £500 all together. When my father dies we shall each have our full share, and I suppose mine will be some hundreds a year ... My ideal would be to live a simple life among the working people, spending on myself whatever seemed to keep me in best efficiency, and giving the rest to public purposes, especially Socialist propaganda of various kinds. I don't suppose I am a very good manager; but I don't think I am careless or extravagant about money. If I married and a fixed income made my husband and myself more free to do the work we thought right, I should think it an advantage to be used. But if you saw this differently, and led me to see as you did; and at the same time we thought that by marrying we could help each other to live fuller and better lives, I would give up the income and try to do my share of pot boiling. I suppose I could do some work for which people would be willing to give money. Of course one ought to consider one's relations as well as oneself; but that is fortunately simple, as any who are worth considering would trust us to do what we thought right. I know your life is a hard one: I know there must be much apparent failure in it, I don't know whether I should have pluck and ability to carry me through anything worth doing: if you ever asked me to be with you it would be a spur to try my best - but there I am getting to the deeper water and will stop.

(2) Margaret Gladstone, letter to Ramsay MacDonald (25th June, 1896)

It is only just beginning to dawn on me a very little bit, since your last Sunday's letter, what a new good gift I have in your love... But when I think how lonely you have been I want with all my heart to make up to you one tiny little bit for that. I have been lonely too - I have envied the veriest drunken tramps I have seen dragging about the streets if they were man and woman because they had each other... This is truly a love letter: I don't know when I shall show it you: it may be that I never shall. But I shall never forget that I have had the blessing of writing it.

(3) Margaret Gladstone, letter to Ramsay MacDonald (2nd July , 1896)

What right have you to talk eloquently about having discovered humanity and then go and say it is wonderful that two poor little bits of humanity should care for each other because they happen to have had rather different circumstances? Not so very different after all, either, for in the most important things we have had the same - we are under the same civilisation - have the same big movements stirring around us - the same books to open our minds; & we both have many good true friends to help us along by their affection. I even have had all my life "darned stockings'"; perhaps you think some magic keeps them from going into holes in the station of life where it has pleased GOD to place me, but I can assure you I have spent many hours darning my own & my father's - badly too...

I don't mind how long you are making up your mind one way or the other - only I would like you to take me on my own merits & not on what my esteemed relations might think of you or what particular kind of summer holiday I had eight years ago. If you want it of course I will bring specimens of my relations to you or you can come to us & I'll have a selection for you to inspect - like animals at the zoo. But I can't introduce them to you without their having some idea of the relations between us, and I certainly at present don't relish the idea of this sort of thing.

(4) David Marquand, Ramsay MacDonald (1977)

When they were first married, MacDonald and Margaret were able to spend most of their evenings together, though, even then, it was a rare week when he had no engagements away from London; and she would sit sewing by the fireside, while he read aloud from Thackeray, Dickens, Scott, Carlyle or Ruskin.

As time went on, however, the demands of political life became heavier; and after a long search they bought a weekend cottage at Chesham Bois, in Buckinghamshire, as a refuge from the pressures of their London lives. MacDonald grew vegetables and standard roses in the garden, and they both spent long hours tramping through the Buckinghamshire countryside - hallowed ground to MacDonald because of its associations with Milton and John Hampden - accompanied by a gaggle of sometimes mutinous children.

As Malcolm remembered them later, these expeditions had an educational purpose as well as a recreational one. MacDonald would tell the children about the trees and flowers that they passed, and talk about the historical associations of the neighbourhood.

(5) Fenner Brockway, Towards Tomorrow (1977)

Ramsay MacDonald was a born leader, with a commanding personality and a magnificent presence; the most handsome man in public life. He was a great orator who deep, resonant voice and sweeping gestures added to the force of his words. He received great help from his wife, a Socialist in the truest sense. Margaret, although of the Gladstone family, contrasted with Ramsay's aristocratic appearance and demeanour. She cared nothing for dress and might have passed for a working-class woman in the days before Marls & Spencer cheap mass-produced clothes. Margaret Bondfield once told me how horrified she was when the wife of the Labour leader turned up with a deputation to 10 Downing Street wearing her blouse back to front.

(6) Ramsay MacDonald, Margaret Ethel Macdonald (1911)

On Thursday, the 20th... she went to Leicester with a member of the Home Office Committee appointed to investigate the management of Industrial Schools; on the morning of Friday she attended a meeting of an Anglo-American Friendship Committee; a little after noon she joined me at the House of Commons with one whom she had desired to meet ever since she had read his book on the negro, Professor Du Bois; that afternoon we went to the country for a weekend rest. She complained of being stiff, and jokingly showed me the finger carrying her marriage and engagement rings. It was badly swollen and discoloured, and I expressed concern. She laughed away my fears: "It is only protesting against its burdens!" On Saturday she was so stiff that she could not do her hair, and she was greatly amused by my attempts to help her. On Sunday she had to admit that she was ill and we returned to town. Then she took to bed.

(7) In his diary, Bruce Glasier recorded the death of Margaret MacDonald's death (September 1911)

Margaret MacDonald might easily have been taken for the nursemaid in a small middle-class family. Her naivete, simplicity, unselfishness and amazing capacity for organisation and helpful work made her one of the best liked women I have known. There was little in her to attract men, as men, but everything to attract women and men who had enthusiasm for public work. What her loss to her husband, one dares not think.

Sir Thomas Barlow came to see her two days before the end, and after examining her called MacDonald into another room. Tears were in his eyes. "The game is up my boy", he said, putting his hand kindly on MacDonald's shoulders. He said he had not the heart to to go back and bid her goodbye.

On MacDonald returning to the bedroom, she asked why Sir Thomas had not returned to say goodbye, she said quietly, then after a moment's thought she looked MacDonald calmly in the eyes: "You must tell me quite truthfully what Sir Thomas said." When she heard that she was doomed, she was silent, and said with a slight tremble in her voice, "I am very sorry to leave you - you and the children - alone." She never wept - never to the end. She asked if the children could be brought to see her. When the boys were brought to her, she spoke to each one separately. To the boys she said, "I wish you only to remember one wish of your mother's - never marry except for love".

(8) Katharine Bruce Glasier, letter to Ramsay MacDonald (December, 1912)

I am gathering courage to tell you how over the fire one night we two wives searched our hearts together & fearlessly said to one another that love like ours had no room for one jealous throb. Mary Middleton had spoken to us unfalteringly of her hope that Jim would "love & live" again in all fullness and I said to Margaret that I knew Bruce's need of the love & sympathy of a true woman so well that were I to go from him my last words would be seek and soon another woman who would mother both him and the bairns for me. And Margaret put her check against mine -a very unusual demonstration - you know - and said, I think it was - "And so would I" - But anyhow I never doubted but we were wholly in sympathy. The feeling that I have to tell you this - almost as if she herself were insisting on it - has been with me for weeks past and I have not dared... But I am too sure of what she would have wished... not to have courage to speak-out now. I was 12 when my mother died and until my father married again when I was nearly 16 I had no home happiness at all. His grief and loneliness put out the sunshine for us children. And the second wife was tenderly good to us. And Margaret - what of her motherhood? It is her will that you live - live to carry on the noblest Socialism in the world today - to live gloriously down every mean aspersion of personal ambition and to accomplish the creation of a strong sane Collectivist Party in Britain capable of government in every sense of the word... She believed in your future and she knew your need of sympathy and help. She told me much of your mother. You know both of us had special reason to love and honour our husbands' mothers and learn from their sorrows and struggles a fiercer morality than any ordinary world holds. We both believed in real marriage: in men and women working shoulder to shoulder - you yourself record that. And here I will stop - proudly holding out both hands to you because I know that she who is gone loved and trusted me and showed me glimpses of her innermost soul.