Discipline and Punishment 1870-1940

On 29th December, 1862, Sheffield played Hallam in a football charity game. It was one of the first-ever football games to be recorded in a newspaper. The Sheffield Independent reported: "At one time it appeared that the match would be turned into a general fight. Major Creswick had got the ball away and was struggling against great odds - Mr Shaw and Mr Waterfall (of Hallam). Major Creswick was held by Waterfall and in the struggle Waterfall was accidentally hit by the Major. All parties agreed that the hit was accidental. Waterfall, however, ran at the Major in the most irritable manner, and struck him several times. He also threw off his waistcoat and began to show fight in earnest. Major Creswick, who preserved his temper admirably, did not return a single blow."

The following week a letter appeared in The Sheffield Independent defending the actions of William Waterfall: "The unfair report in your paper of the... football match played on the Bramall Lane ground between the Sheffield and Hallam Football Clubs calls for a hearing from the other side. We have nothing to say about the result - there was no score - but to defend the character and behaviour of our respected player, Mr William Waterfall, by detailing the facts as they occurred between him and Major Creswick. In the early part of the game, Waterfall charged the Major, on which the Major threatened to strike him if he did so again. Later in the game, when all the players were waiting a decision of the umpires, the Major, very unfairly, took the ball from the hands of one of our players and commenced kicking it towards their goal. He was met by Waterfall who charged him and the Major struck Waterfall on the face, which Waterfall immediately returned."

Fights like this on the pitch were not uncommon during this period. The Football Association was established in October, 1863. The aim of the FA was to establish a single unifying code for football. This included an attempt to deal with disputes about rules and infringements during games. On 8th December, 1863, the FA published the Laws of Football. It was now clear that officials were needed to enforce these new laws. It became fairly common for two umpires to be appointed to referee the game - one nominated by each side. These umpires only made decisions when appealed to by the players. Umpires were first mentioned in the laws of the game in 1874.

As the game became more competitive, the number of disputes about the interpretation of the rules became more common. Gradually, a more objective official, the referee, began to take control of games.

Archie Hunter, who joined Aston Villa in 1876, explained how violence sometimes took place during games: "While I shot for goal the ball skimmed the bar and the Aston Unity goalkeeper immediately caught me round the neck, held me fast and seemed about to deliver a tremendous blow at my face. Everybody saw it; but my rival recovered himself in time and afterwards offered the fullest explanation of his action. I am quite convinced that he had no deliberate intention of doing me any personal injury; he simply lost his self-control for a moment and was unable to restrain himself. In football there are many temptations of this sort and it requires a great amount of good heartedness and coolness to refrain from taking advantage of the proximity of an opponent."

One of the first football players to acquire a national reputation was Arthur Kinnaird. The son of the 10th Lord Kinnaird, he played in nine FA Cup finals, winning five of them with Wanderers (1873, 1877 and 1878) and Old Etonians (1879 and 1882). Kinnaird developed a reputation for hard-tackling. In an article about Kinnaird, Hunter Davies argues that: "On the pitch, he was a fierce competitor, not to say violent. He got stuck in - as we say today: he took no prisoners." His mother, Lady Kinnaird, was concerned that the possibility that her son would be seriously injured. On one occasion she told one of her son's teammates that she feared that he would one day arrive home with a broken leg. "Don't worry, my Lady," he replied. "It won't be his own."

Ernest Needham, who played for England and Sheffield United during this period pointed out: "Once broken limbs from kicks, and broken ribs from charges, were quite every-day occurrences, and, to a great extent, men went on the field with their lives in their hands." Needham believed the shoulder-charge was the main cause of violence on the field.

In 1881 the Football Association introduced a law that stated that if a player was "guilty of ungentlemanly behaviour the referee could rule offending players out of play and order them off the ground." If a player was sent off they were usually suspended for a month without pay.

John Lewis was considered to be the best referee during this period. He later wrote that he was the victim of a great deal of hostility: "For myself, I would take no objection to hooting or groaning by the spectators at decisions with which they disagree. The referee should remember that football is a game that warms the blood of player and looker-on alike, and that unless they can give free vent to their delight or anger, as the case may be, the great crowds we now witness will dwindle rapidly away."

In November 1888, during the first season of the Football League the Sporting Chronicle described how the Everton player, Alec Dick "struck another in the back in a piece of ruffianism". The victim of the assault, Albert Moore, the Notts County, inside-right, was not seriously injured. The newspaper went on to report: "One or two of the Everton team played very hard on their opponents, and hoots and groans were frequent during the match. When the teams left the field a rush was made for the Everton men, who had raised the ire of the spectators, and sticks were used. Dick was singled out, and was struck over the head with a heavy stick, the cowardly fellow was dealt the blow inflicting a severe wound on the side of the Everton man's head."

The Sporting Chronicle added: "Our own correspondent adds that Dick played anything but a gentlemanly game, while his language was coarse; but even these defects did not merit such cowardly and condign punishment as was administered at Trent Bridge". As a result of the incident Alec Dick was suspended by the Football League for the rest of the season.

Officials did not allow players to use "foul and offensive" language on the pitch. On 28th April 1894, Billy Bassett, the England and West Bromwich Albion player, was sent off in a match against Millwall. According to the referee he was dismissed for using "unparliamentary language". Bassett was small and fast and took some very heavy tackles from well-built defenders. In this game he retailed with his tongue and as a result was ordered from the pitch.

Thames Iron Works (later West Ham United) beat Leyton 4-0 at the Memorial Grounds on 2nd October, 1897, with Jimmy Reid getting two of the goals. A crowd of over 3,000 turned up to see the rematch at Leyton's ground later that month. Henry Hird and Robert Hounsell gave the Irons a two goal lead. However, in the second-half, Leyton was awarded a dubious penalty which they converted. Hird, who was still disputing the decision after the goal had been scored, was sent off by the referee. This caused some crowd trouble but the 10 man Hammers held out and even added a third goal, scored by George Gresham, before the end of the game.

The match created a great deal of comment in the West Ham Guardian. The reporter at the game blamed the Hammers for the trouble. "Why will the Thames Ironworks resort to such shady tactics to ensure victory when every member of the team can play good sound football if he likes? Arthur Russell was so badly used by the Ironworkers... that he has since been confined to his bed under the doctor's orders... This roughness should be checked by the Ironwork's committee if they have any regard for the club's good name."

These comments angered supporters of the club and one wrote to the newspaper putting forward a completely different interpretation of the game: "Now as a common or garden onlooker, I emphatically deny that the roughness was all on one side. In the opening stages of the game one of the Leyton halves adopted very shady methods, and this in the main was responsible for the greater portion of the objectionable tactics. Then, too, the ordering off of the outside left (Henry Hird) was sufficient to drive the team to desperation."

Vivian Woodward, who played for England, was only slightly built and he was often the target of some very rough tackling. This resulted him in missing a lot of games through injury. After a game against Fulham on 29th October, 1906, when Woodward took a terrible battering, newspapers called for referees and football authorities to do more to protect skillful players against the crude tactics of defenders.

As the journalist, Arthur Haig-Brown, pointed out in 1903: "It is a 1,000 pities that his lack of weight renders him a temptation which the occasionally unscrupulous half-back finds himself unable to resist." James Catton, Britain's top football journalist at the time, claimed: "He had a great contempt for men who engaged in rough play, because he was the fairest fellow who ever put a boot to a ball. Once after a certain Cup-tie he was really wrath about the way that their opponents had treated his team. It was a replayed match in Lancashire. There was a brother amateur on the other side and he apologised to Woodward for the character of the game that his club had played... Much was required to arouse Vivian John Woodward to resentment because his game was all art and no violence."

Vivian Woodward was never tempted to retailate. As Archie Hunter pointed out: "The best players set their faces very sternly against roughness of all kinds, and some of the finest footballers I know are the most generous and good-natured of men on the field. I don't think much advantage is ever gained by bad temper or spiteful play. If one man is rough, another recriminates; and if one side shows bad blood, the other side is sure to have its bad blood stirred up also. You can play to win and play with perfect fairness; that is my experience."

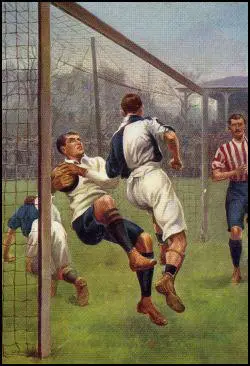

A great deal of rough-play involved the goalkeeper. The shoulder charge remained an important part of the game. This could be used against players even if they did not have the ball. If a goalkeeper caught the ball, he could be barged over the line. As a result, goalkeepers tended to punch the ball a great deal. In 1894 the Football Association introduced a new law which stated that a goalkeeper could only be charged when playing the ball or obstructing an opponent. This new law was not popular with the outfield players. Ernest Needham remarked: "The last part of Rule 10 says, 'The goalkeeper shall not be charged except when he is holding the ball, or obstructing an opponent'; and it is seldom, and not for long, that the custodian is in contact with the ball. It is safe to say that the goalkeeper is the best protected man on the field."

In September, 1898, the South Essex Gazette reported that in a game against Brentford, two West Ham United players, George Gresham and Sam Hay, "bundled the goalkeeper into the net whilst he had the ball in his hands". The goal stood because this action was within the rules at the time.

One man who was unlikely to be barged over the line was William Foulke. A very large man he was nicknamed "Fatty" or "Colossus" by the fans. He once said: "I don't mind what they call me as long as they don't call me late for my lunch." C. B. Fry, the famous cricketer, who also played football for Southampton, remarked: "Foulke is no small part of a mountain. You cannot bundle him."

In a game between Sheffield United and Liverpool in November, 1898, George Allan tried to intimidate Foulke. The Liverpool Post reported that "Allan charged Foulke in the goalmouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him by the leg and turned him upside down."

goal line in a game in 1904.

Games involving two teams from the same town or city often resulted in violent play. In the 1899-1900 season, Sheffield Wednesday played Sheffield United in the second-round of the FA Cup. The first match had to be abandoned owing to a snow storm. The second game resulted in a 1-1 draw at Bramwell Lane. The game had been spoilt by a series of illegal tackles so according to the journalist, James Catton, the referee, John Lewis, "... visited the dressing-room of each set of players, and told them they must observe the laws and spirit of sport. He intimated that if any player committed an offence he would send him off the field."

This warning did not have the desired effect and the replay was one of the roughest in history. James Catton later reported: "In spite of this the tie had not been long in progress when a Wednesday man was sent to the dressing-room for jumping on to an opponent. Soon after that The Wednesday's centre-forward had his leg broken, but that was quite an accident. No blame attached to anyone. Another Wednesday player was ordered out of the arena for kicking an opponent... With two men in the pavilion reflecting on the folly of behaving brutally, and another with a broken leg, it is no wonder that The Wednesday lost the tie. Mr. Lewis always said that this was one of the two most difficult matches he ever had to referee. Memories of this kind abide. His task was formidable, and his duty far from enviable. The sequel was the suspension of two Wednesday players."

On 17th March, 1905, Matt Kingsley was seen to kick former West Ham United player, Herbert Lyon during the game against Brighton & Hove Albion. This caused a crowd invasion and a near riot took place before Kingsley was sent off and Lyon was carried from the field. The Stratford Express reported: "No sooner had the referee pointed to the centre than the West Ham keeper ran at Lyon and kicked him to the ground, and matters looked ugly for the international keeper, who was ordered off the ground by the referee, but the Brighton officials, with a posse of police, acted very promptly and escorted him from the playing arena before any violence was used." It was the last game Kingsley played for West Ham and after completing his suspension he was transferred to Queen's Park Rangers.

Frank Piercy, the captain of West Ham United was another player known for being able to look after himself. The first game of the 1906-07 season the club was at home against Swindon Town. During the game Piercy got involved in a fist fight with the veteran centre-half Charlie Bannister. This is how the Stratford Express described what happened between the two men: "Most of the spectators must have been made angry by the game which took place between West Ham and Swindon at Upton Park on Monday evening. Incidents which reflected discredit on those taking part were frequent, and eventually the game resolved itself into a scramble. One incident - a very regrettable one - will be enough to indicate the kind of game it was. In the second-half Swindon were leading by two goals. One of the Swindon defenders handled the ball, and a penalty was given by the referee. Grassam, in semi-darkness, converted the kick. A West Ham player was walking towards the centre of the field, after the penalty goal had been scored. A Swindon man, who was following him, either accidentally or purposely trod on his heels. The West Ham player - most likely without thinking - turned round and retaliated with his fist. The Swindon man required the services of the trainer before the game proceeded. It is a pity that such unseemly conduct should prevail amongst players of the great national game, for nothing will do more to jeopardise its popularity. And this was not the only incident which occurred; the players were not always particular about their methods of tackling. While everybody likes to see a vigorous display, it is not well to be too vigorous. Whether the matter will go any further it is impossible to say, but it certainly should."

The Football Association agreed with the reporter from the Stratford Express. The referee cautioned Frank Piercy and Charlie Bannister during the game. However, the FA thought this was too lenient and Piercy was banned for four weeks. Bannister, who started the trouble, received a six week suspension.

Frank Piercy was in trouble again when the club played Millwall on 26th October, 1907. Piercy's tackle resulted in Charlie Comrie, Millwall's left-half, being carried from "the field in an unconscious state". Piercy was sent off and suffered his second suspension of the season.

In the period leading up to the First World War, a wing-half named Kenneth Hunt, developed the reputation of being one of the hardest players in the game. Hunt, who played as an amateur, was ordained as a Church of England vicar in 1909. Charlie Buchan, who played with Hunt in the 1910-11 season pointed out that: "The big, strong cleric was noted for his vigorous charging. He delighted in an honest shoulder charge, delivered with all the might of his powerful frame."

Billy Meredith, who played in an international game against Kenneth Hunt, claimed that "I never ran up against a harder or fitter half-back. It was like running up against a brick wall when he charged you... His positioning was perfect. He seldom allowed you a yard of room in which to work. I'm glad I didn't have to meet him very often." However, Hunt, always played by the rules and was just taking advantage of the rule that allowed players to barge into other players.

Charlie Buchan argues in his autobiography, A Lifetime in Football, that Dick Downs, who played for Barnsley between 1908-1919, was the cause of a decline in player discipline. According to Buchan, Downs introduced the sliding tackle. Although it was completely legal, it increased the amount of physical contact. This influenced the way creative footballers played the game: "In my opinion, this tackle which I first saw introduced by Dicky Downs... has done more than anything else, except the change in the offside law in 1925, to alter the character of the game."

In April 1915 Billy Cook, the Oldham Athletic full-back, was playing in a game against Middlesbrough at Ayresome Park. At the time Oldham was challenging for the First Division title. Middlesbrough quickly took a 3-0 goal lead. The Oldham players believed that the third goal should have been disallowed. They were further annoyed when they had a penalty appeal turned down. Early in the second-half Cook fouled Willie Carr and Middlesbrough scored the penalty to extend their lead to 4-1. Soon afterwards Cook brought down Carr again. The referee decided to send off Cook for persistent fouling. However, Cook refused to leave the field and the referee was forced to abandon the match. As a result, Oldham Athletic was fined £350 and Cook was banned by the Football Association for twelve months.

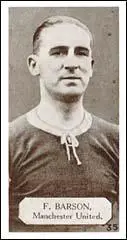

Frank Barson, a tough-tackling defender, was considered to be the hardest player in the Football League in the 1920s. In August 1922 he was transferred to Manchester United for a fee of £5,000. Alex Murphy argues in The Official Illustrated History of Manchester United that: "The club had just been relegated, but they knew exactly what they wanted to revive their fortunes: a tough man to put some steel back into the side and inspire the men around him to win promotion. Barson was the right man. Just the fearsome sight of him was enough to demotivate some opponents: at 6 feet tall Barson loomed over most opponents and he had the sharp features and narrow, menacing eyes of an Aztec warrior."

As Garth Dykes, the author of The United Alphabet has pointed out: "Frank Barson was probably the most controversial footballer of his day. Barrel-chested and with a broken, twisted nose he was a giant amongst centre-halves. A blacksmith by trade, his one failing was that he hardly knew his own strength and was apt to be over impetuous. His desire to always be in the thick of the fray brought him into many conflicts with the game's authorities."

On 27th March 1926, Manchester United played Manchester City in the semi-final of the FA Cup. During the game Sam Cowan was knocked unconscious. It was alleged after the game that Barson had punched Cowan in the face. An investigation by the Football Association resulted in Barson being suspended for eight weeks.

Barson was transferred to Watford in May 1928. Soon afterwards he was sent off in a game against Fulham. It was the 12th time in Barson's career and the Football Association decided to impose a seven-month ban on the player.

In November, 1934, England played against the world champions, Italy. The game was really rough and according to Stanley Matthews: "The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game.... For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me."

Eddie Hapgood later claimed that Wilf Copping led the reaction against the Italians. "Wilf Copping enjoyed himself that afternoon. For the first time in their lives the Italians were given a sample of real honest shoulder charging, and Wilf's famous double-footed tackle was causing them furiously to think." Stanley Matthews added: "Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot."

According to Eddie Hapgood: "The England dressing-room after the match looked like a casualty clearing station. Eric Brook (who had had his elbow strapped up on the field) and I were packed off to the Royal Northern Hospital for treatment, while Drake, who had been severely buffeted, and once struck in the face, Bastin and Bowden were patients in Tom Whittaker's surgery."

On 1st February 1936, Sunderland played Chelsea at Roker Park. According to newspaper reports it was a particularly ill-tempered game and Chelsea's Billy Mitchell, the Northern Ireland international wing-half, was sent off. The visiting forwards appeared to be targeting the Sunderland goalkeeper, Jimmy Thorpe, who took a terrible battering during the match. As a result of the battering he had received, Thorpe was admitted to the local Monkwearmouth and Southwick Hospital suffering from broken ribs and a badly bruised head. Thorpe had also suffered a recurrence of a diabetic condition that he had been treated for two years earlier. Thorpe, who was only 22 years old, died of diabetes mellitus and heart failure on 9th February, 1936.

As a result of the death of Jimmy Thorpe, the Football Association decided to change the rules in order to give goalkeepers more protection from forwards. Players were no longer allowed to raise their foot to a goalkeeper when he had control of the ball in his arms. However, the shoulder charge, remained an important feature in the attempts to intimidate players.

Bill Shankly, who played for Preston North End, was considered one of the hardest tackling defenders playing in the 1930s. In his autobiography, Shankly (1977), he claimed "I was a hard player, but I played the ball, and if you play the ball you'll win the ball and you'll have the man too." Shankly argued that he helped protect skilful team-mates like Tom Finney. "Tommy was injured regularly, and when he was a boy the other players in the team used to look after him a bit in matches. I remember playing in one game when an experienced Scottish player threatened Tommy. He said, 'I'll break your leg.' I heard this, so I went over to the player and I told him, 'Listen, you break his leg and I'll break yours. Then we'll both be finished, because I'll get sent off.' He didn't bother Tommy after that."

Bill Shankly argued in his autobiography that Wilf Copping, who played for Arsenal, was a genuine dirty player who "played the man" rather than the ball. The first time Shankly encountered Copping for the first-time in an international match against England on 9th April, 1938: "Wilf Copping played for England that day, and he was a well-known hard man. The grass was short, the ground was quick, and I was playing the ball. The next thing I knew, Copping had done me down the front of my right leg. He had burst my stocking - the shin-pad was out - and cut my leg. That was after about ten minutes, and it was my first impression of Copping."

The following season Wilf Copping badly damaged Shankly's ankle in a league game against Arsenal. As Shankly later pointed out: "For years afterwards I played with my ankle bandaged and wore a gaiter over my right boot for extra support, and to this day my right ankle is bigger than my left because of what Copping did. My one regret is that he retired from the game before I had a chance to get my own back."

Tommy Lawton also complained about the tackles of Wilf Copping. While playing for Everton against Arsenal in 1938. Lawton constantly beat the Arsenal defenders in the air and Copping warned him that he was "jumping too high" and that he would have to be "brought down to my level". As Lawton later recalled: "Sure enough the next time we both went for a cross, I end up on the ground with blood streaming from my nose. Wilf was looking down at me and he said 'Ah told thee, Tom. Tha's jumping too high!' My nose was broken. when Arsenal came to Everton, Copping broke my nose again! He was hard, Wilf. You always had something to remember him by when you played against him."

A Leeds United historian has provided a good description of the player: "Wilf Copping was the original hard man of English football, paving the way for the likes of Norman Hunter, Ron Harris, Peter Storey, Tommy Smith and Graeme Souness in later decades. However, it is highly debatable whether any of them looked and played the part as well as Copping, with his boxer's nose and build, his unshaven appearance on match days and the bone shaking charges and tackles which were his trademark. Copping, at left half, was liable to unnerve the opposition with just one fixed stare from his craggy face. The harder the going, the more Copping liked it." Jeff Harris argues in his book, Arsenal Who's Who (1995) that Wilf Copping "had the legendary reputation of being more than forceful in the tackle... and that he was the first to admit that he was temperamental and fiery his bone-jarring tackles were mainly timed to perfection and fair". Harris adds that proof that Copping was a clean player is the fact that he played in 340 league games and was never cautioned or sent-off during his career.

Most sides had hardmen whose job it was to protect the more skilful players in the team. For example, Bolton Wanderers had Jack Atkinson to look after Ray Westwood and Albert Geldard. As the authors of Wartime Wanderers point out: "Atkinson was a giant of a centre-half, around whom the entire defence would mould itself. He possessed a no-nonsense attitude on the field that made him the ideal minder for the club's more skilful players. Any opposing defender who chose to stop Ray Westwood by foul means would soon have Jack Anderson chasing after them to mete out instant retribution. In contrast to these extrovert displays of almost naked aggression on the pitch, away from the ground Jack was the archtypal strong, silent type not given to outbursts of emotion."

Primary Sources

(1) The Sheffield Independent (3rd January, 1862)

Hallam played with great determination. They appeared to have many partisans present, and when they succeeded in "downing" a man their ardent friends were more noisily jubilant.

At one time it appeared that the match would be turned into a general fight. Major Creswick had got the ball away and was struggling against great odds - Mr Shaw and Mr Waterfall (of Hallam). Major Creswick was held by Waterfall and in the struggle Waterfall was accidentally hit by the Major. All parties agreed that the hit was accidental. Waterfall, however, ran at the Major in the most irritable manner, and struck him several times. He also "threw off his waistcoat" and began to "show fight" in earnest. Major Creswick, who preserved his temper admirably, did not return a single blow.

There were a few who seemed to rejoice that the Major had been hit and were just as ready to "Hallam" it. We understand that many of the Sheffield players deprecated - and we think not without reason - the long interval in the middle of the game that was devoted to refreshments.

(2) The Sheffield Independent (10th January, 1862)

The unfair report in your paper of the... football match played on the Bramall Lane ground between the Sheffield and Hallam Football Clubs calls for a hearing from the other side. We have nothing to say about the result - there was no score - but to defend the character and behaviour of our respected player, Mr William Waterfall, by detailing the facts as they occurred between him and Major Creswick. In the early part of the game, Waterfall charged the Major, on which the Major threatened to strike him if he did so again. Later in the game, when all the players were waiting a decision of the umpires, the Major, very unfairly, took the ball from the hands of one of our players and commenced kicking it towards their goal. He was met by Waterfall who charged him and the Major struck Waterfall on the face, which Waterfall immediately returned.

(3) The Sporting Chronicle (19th November, 1888)

In the progress of the game Dick of Everton, struck A. E. Moore in the back, a piece of ruffianism which produced a lively verbal encounter. One or two of the Everton team played very hard on their opponents, and hoots and groans were frequent during the match. When the teams left the field a rush was made for the Everton men, who had raised the ire of the spectators, and sticks were used. Dick was singled out, and was struck over the head with a heavy stick, the cowardly fellow was dealt the blow inflicting a severe wound on the side of the Everton man's head. The footballers got separated in the excited crowd, but sturdy Holland and Frank Sugg forced their way to the rescue, and Sugg succeeded in gripping the man who struck Dick. He, however, escaped, though constables arrived quickly. Sugg, Holland, and one or two others protected Dick to the pavilion, where his injuries were attended to. This drastic aspect of football is new to Nottingham, and it is a great pity the perpetrators of this cowardly outrage were not secured and handed over to the police. This we are sure will be the feeling of all respectable people who have the interests of football, of the Notts club, and of the reputation of the town at heart.

Our own correspondent adds that Dick played anything but a gentlemanly game, while his language was coarse; but even these defects did not merit such cowardly and condign punishment as was administered at Trent Bridge by Nottingham "lambs" under mob law.

(4) Archie Hunter, Triumphs of the Football Field (1890)

I may mention one incident in our match with them which shows how players are sometimes carried away by excitement. While I shot for goal the ball skimmed the bar and the Aston Unity goalkeeper immediately caught me round the neck, held me fast and seemed about to deliver a tremendous blow at my face.

Everybody saw it; but my rival recovered himself in time and afterwards offered the fullest explanation of his action. I am quite convinced that he had no deliberate intention of doing me any personal injury; he simply lost his self-control for a moment and was unable to restrain himself. In football there are many temptations of this sort and it requires a great amount of good heartedness and coolness to refrain from taking advantage of the proximity of an opponent.

But the best players set their faces very sternly against roughness of all kinds, and some of the finest footballers I know are the most generous and good-natured of men on the field. I don't think much advantage is ever gained by bad temper or spiteful play. If one man is rough, another recriminates; and if one side shows bad blood, the other side is sure to have its bad blood stirred up also. You can play to win and play with perfect fairness; that is my experience.

(5) Ernest Needham, Association Football (1901)

The popular idea that football is a dangerous game will surely have to undergo modification, but we must acknowledge that it was formerly dangerous. Once broken limbs from kicks, and broken ribs from charges, were quite every-day occurrences, and, to a great extent, men went on the field with their lives in their hands. It is safe to say that now there is no more risk in playing, even a fast game, than there is in any other active sport.

Surely last season's freedom from accident in First Division matches is sufficient evidence of this. I do not remember that any player had a limb broken, and even the Second Division was almost equally free. The object of many changes in the rules has been to extend protection to those engaged, and especially to the goalkeeper. Never now can we see two or three men rush at this isolated guard, while another pops the ball through. To begin with, it is difficult to get near enough to him for a charge without the "off-side rule" coming into operation. Then, again, the last part of Rule 10 says, "The goalkeeper shall not be charged except when he is holding the ball, or obstructing an opponent"; and it is seldom, and not for long, that the custodian is in contact with the ball. It is safe to say that the goalkeeper is the best protected man on the field.

(6) J. A. H. Catton, The Story of Association Football (1926)

It has been my lot, and often my fortune, to watch exciting but fine ties between Everton and Liverpool, Sunderland and Newcastle United (one of these was the cleanest, cleverest, and most sporting match anyone could wish for), Notts County and Nottingham Forest, and West Bromwich Albion and Aston Villa, all neighbours' battles, but this particular match between The Wednesday and United of Sheffield was a bit of old Donnybrook.

Unless I am mistaken the match necessitated three attempts before a settlement. The first match had to be abandoned owing to a snowstorm, the second a week later produced a tie at Bramall Lane (1-1), and the third at Owlerton, two days later (February 19, 1900), resulted in the victory of the United by 2-0. Possibly there was never a more onerous task for a referee. Fortunately the controlling official was the late John Lewis of Blackburn. This tie must linger in memory as a very unpleasant affair.

The first game was typical of Cup-tie football, there being many stoppages for small offences. The replay was on the Monday. Before the game Mr. Lewis visited the dressing-room of each set of players, and told them they must observe the laws and the spirit of sport. He intimated that if any player committed an offence he would send him off the field.

In spite of this the tie had not been long in progress when a Wednesday man was sent to the dressing-room for jumping on to an opponent.

Soon after that The Wednesday's centre-forward had his leg broken, but that was quite an accident. No blame attached to anyone. Another Wednesday player was ordered out of the arena for kicking an opponent.

Mr. Lewis has told me that he did not see this offence, and that his line of sight was obstructed, but he acted, as he had the right to do, on the information of the neutral linesman, Mr. Grant, of Liverpool.

With two men in the pavilion reflecting on the folly of behaving brutally, and another with a broken leg, it is no wonder that The Wednesday lost the tie.

Mr. Lewis always said that this was one of the two most difficult matches he ever had to referee. Memories of this kind abide. His task was formidable, and his duty far from enviable. The sequel was the suspension of two Wednesday players.

For years afterwards it seemed as if ill-feeling between these clubs had died completely out until one day there was a sudden flare-up and a round of fisticuffs between Glennon, of The Wednesday, and W.H. Brelsford, of United. Mr. Clegg was sitting near me and he immediately said: "I thought all this animosity was a thing of the past." Still there was the manifestation-quick and vivid as lightning.

(7) Stratford Express (22nd September, 1906)

At the Boleyn Castle ground on Monday, the home team won by one goal to love. The game was of a vigorous character, and fouls were frequent. Watson and Blackburn were prominent but the visitor's defence, Stevenson and Aitkin, never made a mistake. Dean was seriously hurt in a tussle with Jarvis which caused the Millwall player to retire. This caused a deal of feeling between the sides. West Ham had the best of the play, but at half-time nothing had been scored. After crossing over Comrie had to retire for some minutes for repairs. West Ham were having the best of the play and Stapley forced a corner which proved abortive... Then a penalty against the visitors enabled Kitchen to give West Ham the lead. Comrie retired and Millwall continued to the end with only nine men. Playing the one back game the visitors kept their opponents in hand and nothing further was scored.

(8) Stratford Express (7th September, 1907)

Most of the spectators must have been made angry by the game which took place between West Ham and Swindon at Upton Park on Monday evening. Incidents which reflected discredit on those taking part were frequent, and eventually the game resolved itself into a scramble. One incident - a very regrettable one - will be enough to indicate the kind of game it was. In the second-half Swindon were leading by two goals. One of the Swindon defenders handled the ball, and a penalty was given by the referee. Grassam, in semi-darkness, converted the kick. A West Ham player was walking towards the centre of the field, after the penalty goal had been scored. A Swindon man, who was following him, either accidentally or purposely trod on his heels. The West Ham player - most likely without thinking - turned round and retaliated with his fist. The Swindon man required the services of the trainer before the game proceeded. It is a pity that such unseemly conduct should prevail amongst players of the great national game, for nothing will do more to jeopardise its popularity. And this was not the only incident which occurred; the players were not always particular about their methods of tackling. While everybody likes to see a vigorous display, it is not well to be too vigorous. Whether the matter will go any further it is impossible to say, but it certainly should.

(9) Alan R. Haig-Brown, The Leading Amateurs of Season 1902-03 (1903)

Perhaps the name which was most prominent in football circles during 19O2-3 was that of Vivian Woodward. G.O. Smith had taken his well-earned laurel wreath into seclusion, and an anxious eye was being cast round for his successor. Few thought he was to be found among the ranks of amateurs until the Spurs brought to light young Woodward, and England decided that what was good enough for the London Cup-fighters was good enough for her. He is a player with a great future before him. Though built somewhat on the light side he is clever and tricky, a master of the art of passing. It is a 1,000 pities that his lack of weight renders him a temptation which the occasionally unscrupulous half-back finds himself unable to resist. His record of goals both in League matches and in Internationals is a flattering one, for, all said and done, the most important duty of a centre forward is to find the net, and find it often.

(10) J. A. H. Catton, The Story of Association Football (1926)

But one would never have imagined from his conduct in private life that Woodward was a sportsman - a footballer, a runner, a cricketer, and a great lover of all games as games. He refused to make a profit out of them. It was difficult to induce him to accept even legitimate expenses, which he cut down to the lowest possible figure.

He adored his mother, and it was no uncommon sight to see mother and son wending their way to a match in company. I was introduced to this courtly lady and enjoyed a little chat with her, for she evidently followed football...

Vivian Woodward was one of the most modest of men. And in judgment one of the most charitable. Only once in all the years that we often met did I hear him criticise the conduct of another man. I felt sure that this person deserved more than the mild censure passed upon him - because a harsh remark was so foreign to Woodward's nature.

He had a great contempt for men who engaged in rough play, because he was the fairest fellow who ever put a boot to a ball. Once after a certain Cup-tie he was really wrath about the way that their opponents had treated his team. It was a replayed match in Lancashire. There was a brother amateur on the other side and he apologised to Woodward for the character of the game that his club had played. Woodward did not mind the thrashing that his club had received, but he turned to me and said: "I don't call it football at all. It was brutal."

Much was required to arouse Vivian John Woodward to resentment because his game was all art and no violence. It may be that Woodward had hard experiences in some of his matches against Scotland, while he was played in the centre, but there came a day when he was moved to inside-right, and there he was at his very best - his perfect heading and his deft passes having great effect.

(11) Liverpool Daily Post (29th October, 1898)

Allan charged Foulke in the goalmouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him by the leg and turned him upside down.

(12) Manchester Guardian (31st October, 1898)

McCowie shot in from the left, Foulke caught the ball with one hand, and as Allan dashed up, Foulke used his other hand to collar Allan's leg and upset him.

(13) Athletic News (31st October, 1898)

He (Foulke) got hold of Allan by one of his legs and laid him on the grass.

(14) Graham Phythian, Colossus: The True Story of William Foulke (2005)

One of the subplots of that titanic semi-final series was the running battle between William Foulke and George Allan, the Liverpool inside right. Allan, a high-scoring, combative Glaswegian and Scottish international, was the latest in the succession of forwards who had openly opted for the (usually unrewarding) tactic of the intimidation of Foulke. There was little of the subtlety of a Bloomer or a Meredith in this bull-at-a-gate approach, and it was usually no problem to one who had been a student at the Blackwell Colliery soccer school of hard knocks.

In the League game the previous October, however, there had occurred one of those incidents that has taken on legendary status over the years. It was at Anfield, and the Blades were winning 1-0 from a well-taken Bennett goal. In the second half Liverpool pressed, Foulke collected, and Allan ran at Foulke. What happened next probably took no more than a couple of seconds, and the Liverpool Daily Post's description was unequivocal: "Allan charged Foulke in the goahnouth, and the big man, losing his temper, seized him by the leg and turned him upside down."

From the resultant penalty McCowie scored; then a late own-goal gave Liverpool the points. Almost before the crowd had dispersed at the end of the game the tale was growing in the telling. One version depicted the incident as the culmination of a fiery vendetta between the two players, with William catching Allan by the midriff, turning him over, and planting his head in the mud, giving him such a shock that he never played again.

(15) William Foulke, London Evening News (6th May, 1916)

As the biggest man who ever played football, I have naturally had a few stories told about me, and I should just like to say that some of them are stories.You may have heard that there was a very great rivalry between the old Liverpool centre forward Allan and myself, that prior to one match we breathed fire and slaughter at each other, that at last he made a rush at me as I was saving a shot, and that I dropped the ball, caught him by the middle, turned him clean over in a twinkling, and stood him on his head, giving him such a shock that he never played again.

Well, the story is one which might be described as a "bit of each". In reality, Allan and I were quite good friends off the field. On it we were opponents, of course, and there's no doubt he was ready to give chaff for chaff with me. What actually happened on the occasion referred to was that Allan (a big strong chap, mind you) once bore down on me with all his weight when I was saving.

I bent forward to protect myself, and Allan, striking my shoulder, flew right over me and fell heavily. He had a shaking up, I admit, but quite the worst thing about the whole business was that the referee gave a penalty against us and it cost Sheffield United the match.

There is another story about an Everton forward, Bell, who had threatened me. They will tell you how I got the best of him by bowling him over, then rubbing his nose in the mud, and picking him up with one hand to give him to his trainer to be cared for.

It was really all an accident. Just as I was reaching for a high ball Bell came at me, and the result of the collision was that we both tumbled down, but it was his bad luck to be underneath, and I could not prevent myself front falling with both knees in his back.

At that time I weighed about twenty-two-and-a-half stone, and I knew I must have hurt him, but when I saw his face I got about the worst shock I ever have had on the football field. He looked as if he was dead. I picked him up in my arms as tenderly as a baby, and all I could say was "Oh dear! Oh dear!' But I am happy to say the affair was not so serious as it looked, and the Everton man came round all right.

Nobody is fonder of fun or "devilment" than I am, but nobody who knows me would suggest that I would try to hurt an opponent - though a few of them have hurt me in my time! Talking of fun, I don't mind admitting that I think I had as much as most men during my football career. To my mind almost the best time for a joke is after the team has lost.

When we'd won I was as ready to go to sleep in the railway carriage as anybody. All was peace and comfort then! But when we'd lost I made it my business to be a clown. Once when we were very disappointed I begged some black stuff from the engine driver and rubbed it over my face. There I was sitting on the table and playing some silly game, with all the team round me, laughing like kiddies at a Punch and Judy show, when some grumpy committeeman looked in. Ask the old team, the boys who won the League Championship once and the Cup twice, if a bit of "Little Willie's" foolery didn't help to chirp them up before a tough match.

I sometimes had a hard job to keep my temper on the field, though.You might have thought that forwards would steer clear of such a big chap. Some did, but others seemed to get wild when they couldn't get the ball into goal, and I suffered a lot through kicks administered when the referee wasn't looking.

Although it is more than five years since I gave up playing football, I can still show patches of bruising six inches long on my legs. There is one scar across thee shin which looks as if it will never fairly heal up.

(16) Alex Murphy, The Official Illustrated History of Manchester United (2006)

The club had just been relegated, but they knew exactly what they wanted to revive their fortunes: a tough man to put some steel back into the side and inspire the men around him to win promotion. Barson was the right man. Just the fearsome sight of him was enough to demotivate some opponents: at 6 feet tall Barson loomed over most opponents and he had the sharp features and narrow, menacing eyes of an Aztec warrior.

(17) Garth Dykes, The United Alphabet (1994)

Frank Barson was probably the most controversial footballer of his day. Barrel-chested and with a broken, twisted nose he was a giant amongst centre-halves. A blacksmith by trade, his one failing was that he hardly knew his own strength and was apt to be over impetuous. His desire to always be in the thick of the fray brought him into many conflicts with the game's authorities.

(18) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

During my second home game for Sunderland I got another of those valuable lessons that were offered gratuitously by the great players in those days.

It was in the early stages of the game with Notts County. The left-back opposed to me was a broad-shouldered, thick-set fellow called Montgomery, only about 5ft. 5 in. in height but as tough as the most solid British oak.

The first time I got the ball, I slipped it past him on the outside, darted round him on the inside and finished with a pass to my partner.

It was a trick I had seen Jackie Mordue bring off. It worked wonderfully well. But as I came back down the field, Montgomery said in a low voice: "Don't do that again, son."

Of course I took no notice. The next time I got the ball, I pushed it past him on the outside but that was as far as I got. He hit me with the full force of his burly frame so hard that I finished up flat on my back only a yard from the fencing surrounding the pitch.

It was a perfectly fair shoulder charge that shook every bone in my body. As I slowly crept back on to the field, Montgomery came up and said: "I told you not to do it again."

I never did afterwards. I learned my lesson the painful way and never tried to beat an opponent twice running with the same trick. It made me think up new ways; a very valuable lesson.

(19) Charlie Buchan, A Lifetime in Football (1955)

At the end of the season I was again chosen as England's centre-forward. The match was against Belgium at Brussels.

Soon after the game started, I noticed the Belgium goalkeeper always took three or four strides with the ball before making a clearance. So I awaited my opportunity and, as he was about to kick clear, I put my foot in front of the ball.

It rebounded quickly from the sole of my boot, flew hard up against the cross-bar and bounced clear. If the ball had gone into the net, I think there would have been a riot.

From that moment, the crowd roared every time I got the ball. You see, you are not supposed to go anywhere near a Continental goalkeeper even if he has the ball in his possession.

It is the same now on the Continent. Perhaps there is some excuse for them as the grounds are so hard over there that a goalkeeper is likely to be seriously hurt if he takes a tumble.

It brings back to mind another incident in Vienna with a Continental goalkeeper. He was an enormous chap, inches taller than I and weighing about 15 stone. I charged him when he had the ball in his arms. He went down like a log though the charge was shoulder to shoulder, nothing out of the ordinary.

Almost at once, a stretcher-bearer party appeared and carried him off. A substitute took his place before the game restarted. I came to the conclusion afterwards that the goalkeeper was not really hurt-he wasn't, actually-but that the Viennese wanted a better goalkeeper in his place.

Needless to say, I was not very popular after that charge. I thought there would be trouble before the game was over. There was.

Nearing the end, our right half-back tackled an Austrian, who had the ball at his feet. He, too, went down apparently hurt. The crowd broke on to the field and the game finished abruptly. The crowd were demonstrative but, I am glad to say, not too pugnacious.

Now, with the British Associations back in the F.I.F.A., something may be done about the law relating to charging goalkeepers on the Continent. Our F.A. have had a booklet printed in various languages illustrating the law as it stands, and it has been distributed widely abroad but I fear that our interpretation will never be favourably received outside the British Isles.

There must be a ruling that will be carried out wherever soccer is played, a compromise that will be acceptable both to us and to those abroad. I suggest that it should be on the lines of allowing the goalkeeper undisputed possession in his own six-yard goal area. But it will be a long time before that comes into force.

There is another defensive point that worries me too. It is the sliding tackle which is so prevalent nowadays and which, instead of being a last means of defence, is one of the main tricks in a defender's repertoire.

In my opinion, this tackle which I first saw introduced by Dicky Downs, the sturdy Barnsley miner who afterwards went to Everton, has done more than anything else, except the change in the offside law in 1925, to alter the character of the game.

It is because of this tackle, which of course, comes within the laws, that the game has speeded up so much and consequently lost some of its accuracy. A player cannot pass a ball correctly if he has to do it hurriedly.

It also puts an end to many promising movements. A defender sliding along the ground for a few yards, sometimes from behind, puts the ball into touch or out of play and what might have been a spectacular movement, is brought to a sudden end.

And when a forward is in front of goal, he always has the fear that he will be tackled from behind. So he shoots hurriedly and often wide of the mark.

It brings more injuries to players, too. Coming unexpectedly as it must do, it jars the ankles and the knees of the unfortunate victim. Sooner or later, the player is hurt. Cartilage operations, more or less unknown in the early years of the century, are now commonplace.

Soccer in the old days was tougher and one got more hard shakings from charges and strong tackles but serious injuries were fewer then than they are now. Once you were free of an opponent, there was little fear he would bring you down from behind.

In fact, it was something of a "cold war" in those far-off days. Players tried to frighten you off your game but their bark was much worse than their bite.

I remember one game in Lancashire. As soon as the game started, the left-back came across to me and said: "If you come any of your tricks today, I'll kick you over the grandstand." The left half-back who was standing near, overheard the remark and added: "Yes, and I'll go round the other side and kick you back on the field again."

Yet during the game nothing unusual happened. They played the game fairly and, though they were beaten, never carried out anything like the threats. Sometimes, though, these tactics came off.

There were exceptions, but you soon got to know them. To be warned is to be forearmed and the clever player, without changing his style to any great extent, steered clear of the danger.

But in those days one had a little time, after beating an opponent, to study the next move. As there was no danger from the rear, he could place the ball where he wanted it. Movements of four or five passes were carried out successfully. You do not see them often in these hectic days, mainly because one of the players is brought down by a sliding tackle.Half-backs like Peter McWilliam, Scotland and Newcastle United, or Charlie Roberts of Manchester United and England, would never have dreamed of using this method. They relied upon clever positioning and timely interventions.

(20) Sunderland Football Echo (3rd February, 1936)

Thorpe has shown some excellent goalkeeping this season, but he seldom satisfies me when the ball is crossed. On Saturday his failures had an entirely different origin, and I can come to no other conclusion than that the third goal to Chelsea was due to 'wind up' when he saw Bambrick running up.

(21) Nick Hazlewood, In the Way! Goalkeepers: A Breed Apart? (1996)

In February 1936 Chelsea visited Sunderland and treated them to a brutal afternoon's entertainment in front of 20,000 spectators. It was also an afternoon that witnessed one of the quickest bits of backtracking since Napoleon hit snow in Russia.

Sunderland had been winning 3-1, but in an ill-tempered and poorly controlled game Chelsea pulled back to share the spoils. Police protection was needed to ensure the safety of the referee, and local journalists had no doubt who was to blame - Jimmy Thorpe, the Sunderland keeper. At 3-1 Thorpe had misjudged a ball and failed to clear it from his line and then, two minutes later, worried by the Chelsea striker Bambrick who was haring in, he had taken his eyes off the ball when running to collect a back-pass and allowed it to run over his arm, giving Bambrick his second easy goal in as many minutes...

Thorpe was scared said his critics; he'd turned chicken at the moment of truth. Little did they know that within 48 hours he would be dead. Knocked about on the pitch on the Saturday, Thorpe had suffered a recurrence of a diabetic condition that he had been treated for two years earlier, and which had lain dormant in his body ever since. He died in Monkwearmouth and Southwich Hospital at 2 p.m. on Wednesday afternoon. According to the newspapers there was not the slightest doubt that his death was due to blows received during the match.

(22) Sunderland Football Echo (6th February, 1936)

I know many who would give anything now to feel that they had not uttered the harsh words they spoke in the heat of the moment regarding Jimmy Thorpe's failure to prevent the two Chelsea goals in the second half last week. They did not know that the man whose failures were cursed was actually a hero to carry on at all. Neither did I know, and I confess now that I myself would give anything to have been in the position to have known and never to have given pen to what I wrote.

I do not think he was able to read them and if this is so I am glad that his last days were not saddened by anything I had written because I know he was sensitive about his job... Thorpe will not soon be forgotten.

(23) Sunderland: The Official History (1999)

Following our 3 - 3 draw with Chelsea on 1st February, one of the dailies reported that "Atrocious goalkeeping cost Sunderland a point". The goalkeeping referred to was that of James Thorpe; four days later, he died, baring sustained injuries to both his ribs and his face, the latter resulting in a very swollen eye. In a rough game that saw Chelsea's right half Mitchell being given his marching orders, Thorpe had sustained serious injuries that brought his life to an untimely end. At the subsequent inquest it was revealed that Jimmy suffered from diabetes and took insulin regularly He had fallen into a diabetic coma and the official cause of death was given as both diabetes mellitus and heart failure.

(24) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

When I ran out on to Gigg Lane with the rest of the Stoke team, I was as excited as I had been on my schoolboy international debut, perhaps more so. I noticed there was a cemetery backing on to one end of the ground and just hoped it wasn't an omen - the football career of Stanley Matthews was born and died here!

Within minutes of the kick-off I realised that first-team football was, quite literally, a totally different ball game. Arms were flaying when players came into close contact. Shirts were held. When I tried to get near an opponent with the ball, his arm would shoot out to keep me at bay. When standing alongside my opposite number and the ball came our way, he'd whack an arm across my chest to push me back and to lever himself forward. Whenever I saw a Bury player making progress with the ball and cut across to challenge him, one of his team-mates would run and block my way to allow him to progress. When a high ball came my way, I found I couldn't get off the ground to head it because the player marking me stood on my foot as he jumped to meet the ball with his head. Not once did the referee blow up for any of this. It was my first lesson that in professional football, such things are all part and parcel of the game. You have to accept them otherwise you just wither away. I was soon to learn that the best way of combating all this was to improve my individual skills and technique, to make it harder for my opponent to get near me and the ball. I toiled away, learning from my mistakes.

(25) Bill Shankly, Shankley (1977)

I was a hard player, but I played the ball, and if you play the ball you'll win the ball and you'll have the man too. But if you play the man, that's wrong. Wilf Copping played for England that day, and he was a well-known hard man. The grass was short, the ground was quick, and I was playing the ball. The next thing I knew, Copping had done me down the front of my right leg. He had burst my stocking - the shin-pad was out - and cut my leg. That was after about ten minutes, and it was my first impression of Copping. He was at left half and we came into contact in the middle of the field. I think the pitch was more responsible for what happened than anything, but I was surprised that he would do what he did to me in an international match. He was older than me and had a reputation. He didn't need to be playing at home to kick you -he would have kicked you in your own backyard or in your own chair. He had no fear at all. But while we were fighting for Scotland that day, we didn't go round trying to cripple people.

What Copping did stung me, but I didn't complain about him. I said to him, "Oh, you're making the game a little more important." Frank O'Donnell, who could look after himself, was annoyed at Copping and told him what he thought about it.

Copping had been after me and had caught me and I never contacted him again during the match. But he also hurt me when I played against him for Preston at Highbury on a Christmas Day. One of our players pulled out of a tackle for the ball and I had to go in to fight for it, and Copping caught me on my right ankle.

I was due to play another match the following day, but my ankle had blown up to an awful size. We went from London up to Fleetwood and Bill Scott said, "We'll have a try-out in the morning."

"What do you mean, a try-out?" I asked him, and I soon found out. Next morning my ankle was still badly swollen, and Bill got me a bigger boot to wear on my right foot. My normal size was six and a half, but I put on a size seven and a half or eight that day.

For years afterwards I played with my ankle bandaged and wore a gaiter over my right boot for extra support, and to this day my right ankle is bigger than my left because of what Copping did. My one regret is that he retired from the game before I had a chance to get my own back.

(26) Jeff Harris, Arsenal Who's Who (1995)

Although never cautioned or sent-off during his ten year career he (Wilf Copping) had the legendary reputation of being more than forceful in the tackle, this gave him the nickname of "The Ironman". Although Wilf was the first to admit that he was temperamental and fiery his bone-jarring tackles were mainly timed to perfection and fair. His famous quote was "The first man in a tackle never gets hurt". What added to his misconceived manner on the field was that he never shaved on match days, which gave him a mean blue stubble and more than a fearsome appearance.

(27) Stanley Matthews, The Way It Was (2000)

The game got under way and from the very first tackles, I was left in no doubt that this was going to be a rough house of a game. I wasn't wrong. After a challenge between Drake and Monti, the Italian had to leave the pitch with a broken foot after only two minutes. This only made matters worse. For the first quarter of an hour there might just as well have not been a ball on the pitch as far as the Italians were concerned. They were like men possessed, kicking anything and everything that moved bar the referee. The game degenerated into nothing short of a brawl and it disgusted me...

Ted Drake latched on to an ale-house long ball out of defence and broke away to score a wonderful individual goal on his international debut. He paid for it. Minutes after the game re-started I watched in sadness as Ted was carried from the field, tears in his eyes, his left sock torn apart to reveal a gushing wound.

I thought the three quick goals would calm the Italians down, showing them that rough-house play didn't pay dividends, but they got worse. I felt it was a great shame they had adopted such tactics because individually they were very talented players with terrific on-the-ball skills. They didn't have to resort to rough-house play to win games. Why they had done so this day was beyond me.

Not long after Eric Brook had put us two up, Bertolini hit Eddie Hapgood a savage blow in the face with his elbow as he walked past him. Eddie fell like a Wall Street price in 1929. The next few minutes were dreadful. Tempers flared on both sides, there was a lot of pushing and jostling and punches were exchanged. I abhor such behaviour on the field and when I saw Eddie Hapgood being led off with blood streaming down his face from a broken nose, it sickened me. I'd been really keyed up and looking forward to showing what I could do on the big international scene, but this game was turning into a nightmare.

The game got under way again and the Italians continued where they had left off. It got to a few of our players and I don't mind saying it affected me. Fortunately, we had two real hard nuts in the England side that day in Eric Brook and Wilf Copping who started to dish out as good as they got and more. Wilf was an iron man of a half-back, a Geordie who didn't shave for three days preceding a game because he felt it made him look mean and hard. It did and he was. Eric Brook received a nasty shoulder injury and continued to play manfully with his shoulder strapped up. He was in obvious pain but he just carried on, seemingly ignoring it.

Just before half-time, Wilf Copping hit the Italian captain Monti with a tackle that he seemed to launch from some¬where just north of Leeds. Monti went up in the air like a rocket and down like a bag of hammers and had to leave the field with a splintered bone in his foot. Italy were starting to get the upper hand and laid siege to our goal. It was desperate stuff.

Our dressing room at half-time resembled a field hospital. We were 3-0 up but had paid a bruising price. No one had failed to pick up an injury of one sort of another. The language and comments coming from my England team-mates made my hair stand on end. I was still only 19 but came to the conclusion I'd been leading a sheltered life. I was relieved when our team trainer came into the dressing room, calmed everyone down and said that under no circumstances were we to copy the Italian tactics. We were to go out, he said, and play the way every English team had been taught to play. To do anything but, he said, would exacerbate the situation. Exacerbate the situation? It was already a bloodbath.

(28) (26) Eddie Hapgood, Football Ambassador (1945)

Away we went, and, in fifteen minutes, had the match (apparently) well won. Inside thirty seconds we should have been one up, but Eric Brook's penalty effort was magnificently saved by Ceresoli, the Italian goalkeeper, and a very good one, too. But Eric made up for that. After nine minutes, he headed a cross from Matthews into the net, and, two minutes later, smashed in a second goal from a terrific free kick, taken just outside the penalty area.

Our lads were playing glorious football and the Italians, by this time, were beginning to lose their tempers. Barely had the cheers died down from the 50,000 crowd, than I ran into trouble. The ball went into touch on my side of the field, and, to save time, the Italian right-winger threw the ball in. It went high over me, and, as I doubled back to collar it, the right-half, without making any effort whatsoever to get the ball, jumped up in front of me and carefully smashed his elbow into my face.

I recovered in the dressing-room, with the faint roar from the crowd greeting our third goal (Drake), ringing in my ears, and old Tom working on my gory face. I asked him if my nose was broken, and he, busily putting felt supports on either side, and strapping plaster or, said it was. As soon as he had finished his ministrations, I jumped up and ran out on to the field again.

There was a regular battle going on, each side being a man short - Monti had also left the field after stubbing his toe and breaking a small bone in his foot. The Italians had gone beserk, and were kicking everybody and everything in sight. My injury had, apparently, started the fracas, and, although our lads were trying to keep their tempers, it's a bit hard to play like a gentleman when somebody' closely resembling an enthusiastic member of the Mafia is wiping his studs down your legs, or kicking you up in the air from behind.

Wilf Copping enjoyed himself that afternoon. For the first time in their lives the Italians were given a sample of real honest shoulder charging, and Wilf's famous double-footed tackle was causing them furiously to think.

The Italians had the better of the second half, and, but for herculean efforts by our defence, might have drawn, or even won, the match. Meazza scored two fine goals in two minutes midway through the half, and only Moss's catlike agility kept him from securing his hat-trick and the equaliser. And we held out, with the Italians getting wilder and dirtier every minute and the crowd getting more incensed. One of the newspaper men was so disgusted with the display that he signed his story "By Our War Correspondent."

The England dressing-room after the match looked like a casualty clearing station. Eric Brook (who had had his elbow strapped up on the field) and I were packed off to the Royal Northern Hospital for treatment, while Drake, who had been severely buffeted, and once struck in the face, Bastin and Bowden were patients in Tom Whittaker's surgery.