On this day on 31st March

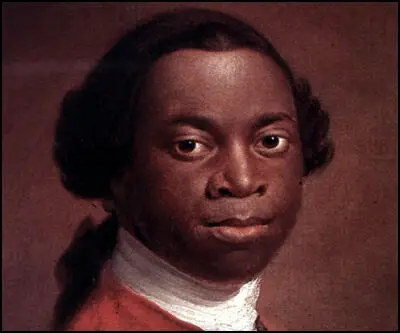

On this day in 1797 Olaudah Equiano died. Equiano was born in Essaka, an Igbo village in the kingdom of Benin (now Nigeria) in 1745. His father was one of the province's elders who decided disputes. According to James Walvin "Equiano described his father as a local Igbo eminence and slave owner".

When he was about eleven, Equiano was kidnapped and after six months of captivity he was brought to the coast where he encountered white men for the first time. Equiano later recalled in his autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African (1787): "The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast, was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror, when I was carried on board. I was immediately handled, and tossed up to see if I were sound, by some of the crew; and I was now persuaded that I had gotten into a world of bad spirits, and that they were going to kill me. Their complexions, too, differing so much from ours, their long hair, and the language they spoke, (which was very different from any I had ever heard) united to confirm me in this belief. Indeed, such were the horrors of my views and fears at the moment, that, if ten thousand worlds had been my own, I would have freely parted with them all to have exchanged my condition with that of the meanest slave in my own country."

Olaudah Equiano was placed on a slave-ship bound for Barbados. "I was soon put down under the decks, and there I received such a greeting in my nostrils as I had never experienced in my life; so that, with the loathsomeness of the stench, and crying together, I became so sick and low that I was not able to eat, nor had I the least desire to taste anything. I now wished for the last friend, death, to relieve me; but soon, to my grief, two of the white men offered me eatables; and, on my refusing to eat, one of them held me fast by the hands, and laid me across, I think, the windlass, and tied my feet, while the other flogged me severely. The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us. The air soon became unfit for respiration, from a variety of loathsome smells, and brought on a sickness among the slaves, of which many died. The wretched situation was again aggravated by the chains, now unsupportable, and the filth of the necessary tubs, into which the children often fell, and were almost suffocated. The shrieks of the women, and the groans of the dying, rendered the whole a scene of horror almost inconceivable."

After a two-week stay in the West Indies Equiano was sent to the English colony of Virginia. In 1754 he was purchased by Captain Henry Pascal, a British naval officer. He was given the new name of Gustavus Vassa and was brought back to England. According to his biographer, James Walvin: "For seven years he served on British ships as Pascal's slave, participating in or witnessing several battles of the Seven Years' War. Fellow sailors taught him to read and write and to understand mathematics. He was also converted to Christianity, reading the Bible regularly on board ship. Baptized at St Margaret's Church, Westminster, on 9 February 1759, he struggled with his faith until finally opting for Methodism."

By the end of the Seven Years' War he reached the rank of able seaman. Although he was freed by Pascal he was re-enslaved in London in 1762 and shipped to the West Indies. For four years he worked for a Montserrat based merchant, sailing between the islands and North America. "I was often a witness to cruelties of every kind, which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves. I used frequently to have different cargoes of new Negroes in my care for sale; and it was almost a constant practice with our clerks, and other whites, to commit violent depredations on the chastity of the female slaves; and these I was, though with reluctance, obliged to submit to at all times, being unable to help them." James Walvin points out that "Equiano... also trading to his own advantage as he did so. Ever alert to commercial openings, Equiano accumulated cash and in 1766 bought his own freedom."

Equiano now worked closely with Granvile Sharpe and Thomas Clarkson in the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Equiano spoke at a large number of public meetings where he described the cruelty of the slave trade. In 1787 Equiano helped his friend, Offobah Cugoano, to published an account of his experiences, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of America. Copies of his book was sent to George III and leading politicians. He failed to persuade the king to change his opinions and like other members of the royal family remained against abolition of the slave trade.

Equiano published his own autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano the African in 1789. He travelled throughout England promoting the book. It became a bestseller and was also published in Germany (1790), America (1791) and Holland (1791). He also spent over eight months in Ireland where he made several speeches on the evils of the slave trade. While he was there he sold over 1,900 copies of his book.

David Dabydeen has argued: "With Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, Equiano was a major abolitionist, working ceaselessly to expose the nature of the shameful trade. He travelled throughout Britain with copies of his book, and thousands upon thousands attended his readings. When John Wesley lay dying, it was Equiano's book he took up to reread."

On 7th April 1792 Equiano married Susanna Cullen (1761-1796) of Soham, Cambridgeshire. The couple had two children, Anna Maria (16th October 1793) and Johanna (11th April 1795). However, Anna Maria died when she was only four years old. Equiano's wife died soon afterwards. During this period he was a close friend of Thomas Hardy, secretary of the London Corresponding Society. Equiano became an active member of this group that campaigned in favour of universal suffrage.

Olaudah Equiano was appointed to the expedition to settle former black slaves in Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa. However, he died at his home at Paddington Street, Marylebone, on 31st March, 1797 before he could complete the task.

The historian, James Walvin, has argued: "After his death his book was anthologized by abolitionists (especially before the American Civil War). Thereafter, however, Equiano was virtually forgotten for a century. In the 1960s his autobiography was rediscovered and reissued by Africanist scholars; various editions of his Narrative have since sold in large numbers in Britain, North America, and Africa. Equiano's autobiography remains a classic text of an African's experiences in the era of Atlantic slavery. It is a book which operates on a number of levels: it is the diary of a soul, the story of an autodidact, and a personal attack on slavery and the slave trade. It is also the foundation-stone of the subsequent genre of black writing; a personal testimony which, however mediated by his transformation into an educated Christian, remains the classic statement of African remembrance in the years of Atlantic slavery." Chinua Achebe has called him "the father of African literature" whereas Henry Louis Gates claimed him for America as "the founding father of the Afro-American literary tradition".

In 2005 Vincent Carretta published his book, Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man. He argued that he had found a document that suggests that Equiano was really born in South Carolina. As David Dabydeen points out: "In other words, Equiano may never have set foot in Africa, never mind boarded a slave ship, and the narrative of his early life may be pure fiction." However, he adds: "Equiano's autobiography, Carretta suggests, is a monumental 18th-century text, a unique mixture of travel-writing, sea lore, sermon, economic tract and fiction. That the early chapters may have invented a life in Africa only adds to our appreciation of Equiano's imaginative depth and literary talent."

On this day in 1823 Mary Boykin Chesnut was born. Mary Miller was born in Pleasant Hill, South Carolina, on 31st March, 1823. The daughter of Stephen Miller, the governor of South Carolina, and Mary Boykin, Mary attended private schools in Camden and Charleston.

On 23rd April, 1840, Mary married James Chesnut, the owner of a large plantation in Mulberry, South Carolina. When Chesnut was elected to the Senate in 1858, Mary accompanied her husband to Washington.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War Chesnut joined the Confederate Army and became a military aide to General P. G. T. Beauregard. Promoted to the rank of general, Chesnut worked as an advisor to President Jefferson Davis. Mary always accompanied her husband during the war and spent time in Charleston, Montgomery, Columbia and Richmond.

Chesnut was opposed to slavery but believed in the right of the Southern states to leave the Union. Between February, 1861 and July, 1865, Chesnut kept a 400,000 word diary of the conflict.

After the war Mary Boykin Chesnut wrote three novels. However, none of these were published during her lifetime. Mary Boykin Chesnut died in Camden, South Carolina, on 22nd November, 1886. Her book, A Diary From Dixie, was not published until 1905.

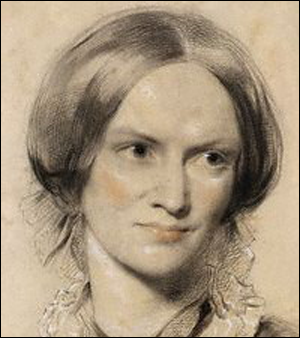

On this day in 1855 Charlotte Brontë died. Charlotte, the daughter of Patrick Bronte and Mary Bronte, was born on 21st April 1816. When Charlotte was a small child, her father became curate in the village of Haworth. Charlotte's mother died in 1821, leaving five daughters and a son, to be looked after by an aunt, Elizabeth Branwell.

In 1824 Charlotte, and three of her sisters, was sent to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge. Conditions at the school were appalling and after two of her sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died of consumption, Charlotte and Emily were brought home. For the next six years, the four surviving children, were left to look after themselves. They spent the time at Haworth telling and writing stories about fantasy worlds they had created.

Patrick Bronte decided in 1831 that Charlotte should continue her education and was sent to a Miss Wooler, who ran a school at Roe Head. This time she was treated well and while at the school made two life-long friends, Mary Taylor and Ellen Nussey.

When Charlotte was 19 she was offered a post as assistant teacher at Roe Head. After she returned home in 1839 she turned down a proposal of marriage from Ellen's brother, the Rev. Henry Nussey, and instead became a governess at Skipton. This was followed by posts as a governess to a family in Leeds and as a pupil-teacher in Brussels. While at the school Charlotte fell desperately in love with her teacher, Constantin Heger. He was married and showed no signs of returning her love.

Charlotte Brontë returned to England and began to write. She was unable to find a publisher for her first novel, The Professor, but she was more successful with Jane Eyre (1847), a novel based on her experiences at the Clergy Daughters' School. Published under the name, Currer Bell, the novel achieved immediate success.

Soon afterwards, her sisters also had novels published. Anne Bronte achieved success with Agnes Grey (1847) and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) and Emily Bronte published Wuthering Heights just before her death from consumption in 1848. Over the next few months Charlotte's brother Branwell and sister, Anne, both died from this disease.

Charlotte continued to write and published Shirley in 1849. She also became friends with Elizabeth Gaskell, who was later to write her biography. Villette, a novel inspired by her unrequited love for Constantin Heger, was published in 1853.

Charlotte married her father's curate, Rev. Arthur Bell Nicholls in 1854. Charlotte Brontë immediately became pregnant and this created medical problems and she died on 31st March, 1855.

On this day in 1889 a protest meeting took place because of workers from the Beckton Gas Works being laid off. One of the speakers at the meeting, Will Thorne, suggested that the gas workers formed their own union to protect themselves from the power of their employers. Thorne told the assembled men "I pledge my word that, if you will stand firm and don't waver, within six months we will claim and win the eight-hour day, a six-day week and the abolition of the present slave-driving methods in vogue not only at the Beckton Gas Works, but all over the country."

Will Thorne, Ben Tillett and William Byford formed a three man committee and that morning they recruited over 800 members. The committee then had responsibility of forming what became known as the National Union of Gasworkers & General Labourers. Elections were held and Thorne defeated Tillett for the post of General Secretary of the union.

Some members of the committee wanted the union to negotiate a 1s. a day increase in their wages. Will Thorne favoured a reduction in working hours, arguing that "the eight-hour day would not alone mean a reduction of four hours a day for the workers then employed, but that it meant a large number of unemployed would be absorbed, and so reduce the inhuman competition that was making men more like beasts than civilized persons.".

Thorne won the argument and began negotiations with the owners of the Gas Light and Coke Company, Beckton Gas Works and Nine Elms Gas Works. Within a few weeks Thorne had successfully negotiated an eight hour day in the industry. As they previously did twelve hour shifts, this was a great advert for union power and the Gasworkers' Union soon had over 20,000 members.

On this day in 1898 Eleanor Marx commits suicide. In 1884 Eleanor became involved with Edward Aveling. The two shared the same views on politics and religion and Aveling made his living from giving lectures on these subjects. As Aveling was already married, Eleanor lived with him as his common law wife. In January 1898, Aveling became seriously ill, and Eleanor spent many months nursing him back to health. Soon afterwards she discovered that Aveling had secretly married another woman. Unable to bear the pain of this latest betrayal, Eleanor Marx committed suicide.

On this day in 1918 The Daily Herald holds a meeting that welcomed the Russian Revolution. William Norman Ewer reports included an interview with Leon Trotsky. According to Stanley Harrison, the author of Poor Men's Guardians (1974): "It was the first of a series of huge meetings in the Albert Hall to welcome the Revolution and demand in general terms that all governments follow the Russian example in restoring freedom. twelve thousand people filled every seat and five thousand were turned away."

The newspaper also campaigned against British intervention in the Russian Civil War. The Trade Union Congress resolved that all action necessary, including a general strike, would be taken to prevent war. David Lloyd George and his government backed down but claimed that editor George Lansbury was in the pay of the Bolsheviks. Lansbury at once published the complete list of the persons and organisations who had provided the newspaper with money. The audited circulation figures of 329,869, convinced the government that The Daily Herald had the support of the public and it withdrew its claims.

On this day in 1921 Poplar Council set a rate that meant Labour councillors would end up in prison. In November 1919 the Labour Party had won 39 of the 42 council seats. In 1921 Poplar had a rateable value of £4m and 86,500 unemployed to support. Whereas other more prosperous councils could call on a rateable value of £15 to support only 4,800 jobless. George Lansbury proposed that the Council stop collecting the rates for outside, cross-London bodies. This was agreed and on 31st March 1921, Poplar Council set a rate of 4s 4d instead of 6s 10d. On 29th the Councillors were summoned to Court. They were told that they had to pay the rates or go to prison. At one meeting Millie Lansbury said: "I wish the Government joy in its efforts to get this money from the people of Poplar. Poplar will pay its share of London's rates when Westminster, Kensington, and the City do the same."

On 28th August over 4,000 people held a demonstration at Tower Hill. The banner at the front of the march declared that "Popular Borough Councillors are still determined to go to prison to secure equalisation of rates for the poor Boroughs." The Councillors were arrested on 1st September. Five women Councillors, including Julia Scurr, Millie Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, were sent to Holloway Prison. Twenty-five men, including George Lansbury and John Scurr, went to Brixton Prison. On 21st September, public pressure led the government to release Nellie Cressall, who was six months pregnant. Julia Scurr reported that the "food was unfit for any human being... fish was given on Friday, they told us, that it was uneatable, in fact, it was in an advanced state of decomposition".

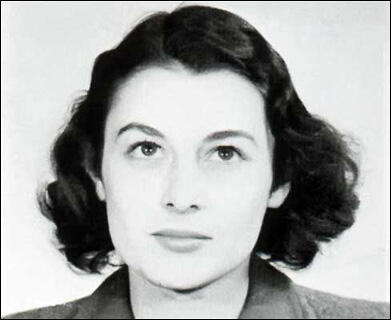

On this day in 1946 the News of the World reports on the death of Violette Szabo. During the Second World War Violette Bushell met Etienne Szabo, an officer in the Free French Army. The couple decided to get married (21st August 1940) when they discovered that Etienne was about to be sent to fight in North Africa.

Soon after giving birth to a daughter, Tania Szabo, Violette heard that her husband had been killed at El Alamein. She now developed a strong desire to get involved in the war effort and eventually joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE). She told a fellow recruit: "My husband has been killed by the Germans and I'm going to get my own back."

At first SOE officers had doubts about whether Violette should be sent to France. One officer wrote: "She speaks French with an English accent. Has no initiative; is completely lost when on her own. Another officer argued: "This student is temperamentally unsuitable... When operating in the field she might endanger the lives of others."

Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, head of SOE's French operations, overruled these objections and after completing her training Violette was parachuted into France where she had the task of obtaining information about the resistance possibilities in the Rouen area. Despite being arrested by the French police she completed her mission successfully and after being in occupied territory for six weeks she returned to England.

Violette Szabo returned to France in June 1944 but while with Jacques Dufour, a member of the French Resistance, was ambushed by a German patrol. By providing covering fire Szabo enabled Dufour to escape. Szabo was captured and taken to Limoges and then to Paris. After being tortured by the Gestapo she was sent to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in Germany.

Some time in the spring of 1945, with Allied troops closing in on Nazi Germany, Violette Szabo was executed. She was posthumously awarded the Croix de Guerre and the George Cross. Her story is told in the book and film entitled Carve Her Name With Pride.

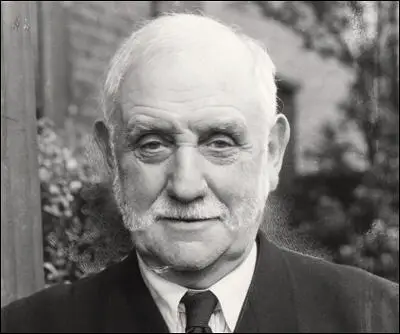

On this day in 1981 novelist Enid Bagnold died of bronchopneumonia on 31st March 1981 at 17a Hamilton Terrace, London. Her ashes were buried at Rottingdean, Sussex, after her cremation at Golders Green.

Enid Bagnold, the daughter of Colonel Arthur Henry Bagnold, the Commander of the Royal Engineers, was born in Rochester, Kent on 27th October, 1889. Her early childhood was spent in Jamaica but was educated at Prior's Field School in Godalming.

According to Nigel Nicolson she was "a tomboyish, dramatic, outdoor, beautiful girl who soon escaped the conventionally respectable life of her parents by taking a flat in Chelsea". While living in London she studied art under Walter Sickert.

In August 1913, Frank Harris began a magazine entitled, Modern Society. He employed Enid as a staff writer. She later recalled: "He was an extraordinary man. He had an appetite for great things and could transmit the sense of them. He was more like a great actor than a man of heart. He could simulate anything. While he felt admiration he could act it, and while he acted it, he felt it. And greatness being his big part, he hunted the centuries for it, spotting it in literature, in passion, in action."

In her Autobiography (1917) she admitted that Harris took her virginity. "The great and terrible step was taken... I went through the gateway in an upper room in the Cafe Royal. That afternoon at the end of the session I walked back to Uncle Lexy's at Warrington Crescent, reflecting on my rise. Like a corporal made sergeant.... And what about love - what about the heart? It wasn't involved. I went through this adventure like a boy, in a merry sort of way, without troubling much. I didn't know him. If I had really known him I might have been tender." During dinner with Uncle Lexy she later wrote that she couldn't believe that her skull wasn't chanting aloud: "I'm not a virgin! I'm not a virgin".

Harris introduced her to people like Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Katherine Mansfield, John Middleton Murry and Claud Lovat Fraser. Gaudier-Brzeska asked her to pose for him. She later recalled: "He didn't want to know what people were like. He rushed at them, held them, poured his thoughts over them, and when in response, they said ten words his impatience overflowed; he jabbed and wounded and the blood flowed."

Enid Bagnold has left an interesting account of what it was like to be sculptured by Gaudier-Brzeska: "I went to his room in Chelsea - a large, bare room at the top of a house - it was winter, and the daylight would not last long. While I sat still, idle and uncomfortable on a wooden chair, Gaudier's thin body faced me, standing in his overall behind the lump of clay, at which he worked with feverish haste. We talked a little, and then fell silent; from time to time, but not very often, his black eyes shot over my face and neck, while his hands flew round the clay. After a time his nose began to bleed, but he made no attempt to stop it; he appeared insensible to it, and the blood fell on to his overall."

On the outbreak of the First World War Bagnold joined the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) and worked as a nurse at the Royal Herbert Hospital, Woolwich. Her account of this experience, Diary Without Dates (1917) was so critical of hospital administration that the military authorities arranged for her dismissal. H. G. Wells described it as one of the most human books written about the war. Determined to help the war effort, Bagnold went to France and worked as a volunteer driver. Later she wrote about this in The Happy Foreigner (1920).

In 1920 Bagnold married Roderick Jones, the head of Reuters News Agency. They moved to North End House, Rottingdean. The writer, Anne Sebba, has argued "Their partnership was marked by loyalty, not fidelity, respect but not passion". The couple had four children. three sons and a daughter. Her friend Vita Sackville-West wrote of her in an unpublished poem: "And then came Jones, and flesh succumbed to Jones and domesticity destroyed you in the end."

Bagnold continued to write and in 1924 published the highly acclaimed novel, The Difficulty of Getting Married. Her biographer, Nigel Nicolson has argued: "Enid Bagnold thus achieved fame while still in her twenties, and her ambition never slackened. Her vitality, humour, audacity, and grace made her an exhilarating companion. She was ebulliently communicative, in talk as in writing, as lavish with words as a pianist is with notes, loving the inexhaustible variety of human experience as much as the language which expressed it."

This was followed by the commercially successful, National Velvet (1935), the story of a butcher's daughter who wins a horse in a raffle and, disguised as a boy, she rides to victory in the Grand National. It was later made into a hugely successful film, with Elizabeth Taylor in the starring role. Her next novel, which she considered to be her best, was The Squire (1938).

Bagnold also wrote several popular plays including Lottie Dundass (1943), The Chalk Garden (1951), The Chinese Prime Minister (1964) and a Matter of Gravity (1975).

Enid Bagnold died of bronchopneumonia on 31st March 1981 at 17a Hamilton Terrace, London. Her ashes were buried at Rottingdean, Sussex, after her cremation at Golders Green.

On this day in 1998 Bella Abzug died. Bella Savitzky (Abzug) was born in New York City on 24th July 1920. After attending local public schools she obtained a degree from the Columbia University Law School in 1945.

Admitted to the New York Bar in 1947, Abzug concentrated on trade union and civil rights cases. This included the Willie McGee case. McGee, a 36-year-old black truck driver from Laurel, Mississippi, was convicted of raping a white woman despite evidence that the couple had been having a relationship for four years. The trial lasted less than a day and the jury took under three minutes to reach a verdict and the judge sentenced McGee to be executed. Abzug argued that no white man had ever been condemned to death for rape in the deep South, while over the last forty years 51 blacks had been executed for this offence.

Despite a nationwide campaign led by the American Communist Party McGee was executed on 8th May 1951. It was claimed by James Cogley wrote in Commonweal: "The Communists vigorously espoused McGee's cause, but their support nowadays is rather a kiss of death." Mary Mostert, writing in The Nation agreed: "Willie McGee was convicted because he was black and supported by Communists, not on any conclusive evidence."

Abzug also represented a large number of left-wing activists who were persecuted by Joseph McCarthy and the Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). During this period Abzug was described by McCarthy as one if the most subversive lawyers in the country.

Bella Abzug was a strong opponent of the Vietnam War and was an initiator of Women Strike for Peace Movement that was established in 1961.

A member of the Democratic Party, Abzug was elected to the 92nd Congress. She was also successful in the 93rd and 94th and served between January 1971 and January 1977. During this period she campaigned for the immediate withdrawal of the U.S. Army from Vietnam, a Freedom of Information Act, gay and lesbian civil rights, the Equal Rights Amendment and comprehensive child care.

Abzug was an unsuccessful candidate for nomination to the United States Senate in 1977. She was co-chair of the National Advisory Committee for Women (1978-79) and the co-founder of the Women's Environmental and Development Organization (WEDO).