On this day on 30th May

On this day in 1381 the people of Fobbing refuse to pay their poll tax and therefore start the Peasants Revolt. Thomas Bampton, the Tax Commissioner for the Essex area, reported to the king that the people of Fobbing were refusing to pay their poll tax. It was decided to send a Chief Justice and a few soldiers to the village. It was thought that if a few of the ringleaders were executed the rest of the village would be frightened into paying the tax. However, when Chief Justice Sir Robert Belknap arrived, he was attacked by the villagers.

Belknap was forced to sign a document promising not to take any further part in the collection of the poll tax. According to the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's: "The Commons rose against him and came before him to tell him... he was maliciously proposing to undo them... Accordingly they made him swear on the Bible that never again would he hold such sessions nor act as Justice in such inquests... And Sir Robert travelled home as quickly as possible."

After releasing the Chief Justice, some of the villagers looted and set fire to the home of John Sewale, the Sheriff of Essex. Tax collectors were executed and their heads were put on poles and paraded around the neighbouring villages. The people responsible sent out messages to the villages of Essex and Kent asking for their support in the fight against the poll tax.

Many peasants decided that it was time to support the ideas proposed by John Ball and his followers. It was not long before Wat Tyler, a former soldier in the Hundred Years War, emerged as the leader of the peasants. Tyler's first decision was to march to Maidstone to free John Ball from prison. "John Ball had been set free and was safe among the commons of Kent, and he was bursting to pour out the passionate words which had been bottled up for three months, words which were exactly what his audience wanted to hear."

Charles Poulsen, the author of The English Rebels (1984) has pointed out that it was very important for the peasants to be led by a religious figure: "For some twenty years he had wandered the country as a kind of Christian agitator, denouncing the rich and their exploitation of the poor, calling for social justice and freeman and a society based on fraternity and the equality of all people." John Ball was needed as their leader because alone of the rebels, he had access to the word of God. "John Ball quickly assumed his place as the theoretician of the rising and its spiritual father. Whatever the massess thought of the temporal Church, they all considered themselves to be good Catholics."

On 5th June there was a revolt at Dartford and two days later Rochester Castle was taken. The peasants arrived in Canterbury on 10th June. Here they took over the archbishop's palace, destroyed legal documents and released prisoners from the town's prison. More and more peasants decided to take action. Manor houses were broken into and documents were destroyed. These records included the villeins' names, the rent they paid and the services they carried out. What had originally started as a protest against the poll tax now became an attempt to destroy the feudal system.

The peasants decided to go to London to see Richard II. As the king was only fourteen-years-old, they blamed his advisers for the poll tax. The peasants hoped that once the king knew about their problems, he would do something to solve them. The rebels reached the outskirts of the city on 12 June. It has been estimated that approximately 30,000 peasants had marched to London. At Blackheath, John Ball gave one of his famous sermons on the need for "freedom and equality".

Wat Tyler also spoke to the rebels. He told them: "Remember, we come not as thieves and robbers. We come seeking social justice." Henry Knighton records: "The rebels returned to the New Temple which belonged to the prior of Clerkenwell... and tore up with their axes all the church books, charters and records discovered in the chests and burnt them... One of the criminals chose a fine piece of silver and hid it in his lap; when his fellows saw him carrying it, they threw him, together with his prize, into the fire, saying they were lovers of truth and justice, not robbers and thieves."

Charles Poulsen praises Wat Tyler as learning the "lessons of organisation and discipline" when in the army and in showing the "same pride in the customs and manners of his own class as the noblest baron would for his". The medieval historians were less complimentary and Thomas Walsingham described him as a "cunning man, endowed with much sense if he had applied his intelligence to good purposes".

Richard II gave orders for the peasants to be locked out of London. However, some Londoners who sympathised with the peasants arranged for the city gates to be left open. Jean Froissart claims that some 40,000 to 50,000 citizens, about half of the city's inhabitants, were ready to welcome the "True Commons". When the rebels entered the city, the king and his advisers withdrew to the Tower of London. Many poor people living in London decided to join the rebellion. Together they began to destroy the property of the king's senior officials. They also freed the inmates of Marshalsea Prison.

Part of the English Army was at sea bound for Portugal whereas the rest were with John of Gaunt in Scotland. Thomas Walsingham tells us that the king was being protected in the Tower by "six hundred warlike men instructed in arms, brave men, and most experienced, and six hundred archers". Walsingham adds that they "all had so lost heart that you would have thought them more like dead men than living; the memory of their former vigour and glory was extinguished". Walsingham points out that they did not want to fight and suggests they may have been on the side of the peasants.

John Ball sent a message to Richard II stating that the rising was not against his authority as the people only wished only to deliver him and his kingdom from traitors. Ball also asked the king to meet with him at Blackheath. Archbishop Simon Sudbury and Robert Hales, the treasurer, both objects of the people's hatred, warned against meeting the "shoeless ruffians", whereas others, such as William de Montagu, the Earl of Salisbury, urged that the king played for time by pretending that he desired a negotiated agreement.

Richard II agreed to meet the rebels outside the town walls at Mile End on 14th June, 1381. Most of his soldiers remained behind. Charles Oman, the author of The Great Revolt of 1381 (1906), pointed the "ride to Mile End was perilous: at any moment the crowd might have broken loose, and the King and all his party might have perished... nevertheless, though surrounded all the way by a noisy and boisterous multitude, Richard and his party ultimately reached Mile End".

When the king met the rebels at 8.00 a.m. he asked them what they wanted. Wat Tyler explained the demands of the rebels. This includes the end of all feudal services, the freedom to buy and sell all goods, and a free pardon for all offences committed during the rebellion. Tyler also asked for a rent limit of 4d per acre and an end to feudal fines through the manor courts. Finally, he asked that no "man should be compelled to work except by employment under a regularly reviewed contract".

The king immediately granted these demands. Wat Tyler also claimed that the king's officers in charge of the poll tax were guilty of corruption and should be executed. The king replied that all people found guilty of corruption would be punished by law. The king agreed to these proposals and 30 clerks were instructed to write out charters giving peasants their freedom. After receiving their charters the vast majority of peasants went home.

G. R. Kesteven, the author of The Peasants' Revolt (1965), has pointed out that the king and his officials had no intention of carrying out the promises made at this meeting, they "were merely using those promises to disperse the rebels". However, Wat Tyler and John Ball were not convinced by the word given by the king and along with 30,000 of the rebels stayed in London.

While the king was in Mile End discussing an agreement with the king, another group of peasants marched to the Tower of London. There were about 600 soldiers defending the Tower but they decided not to fight the rebel army. Simon Sudbury (Archbishop of Canterbury), Robert Hales (King's Treasurer) and John Legge (Tax Commissioner), were taken from the Tower and executed. Their heads were then placed on poles and paraded through the streets of cheering Londoners.

Rodney Hilton argues that the rebels wanted revenge on all those involved in the levying of taxes or the administrating the legal system. Roger Leggett, one of the most important government lawyers was also killed. "They attacked not only the lawyers themselves - attorneys, pleaders, clerks of the courts - but others closely associated with the judicial processes... The hostility to lawyers and to legal records was not of course peculiar to the Londoners. The widespread destruction of manorial court records is well-known" during the rebellion.

The rebels also attacked foreign workers living in London. "The commons made proclamation that every one who could lay hands on Flemings or any other strangers of other nations might cut off their heads". It has been claimed that "some 150 or 160 unhappy foreigners were murdered in various places - thirty-five Flemings in one batch were dragged out of the church of St. Martin in the Vintry, and beheaded on the same block... The Lombards also suffered, and their houses yielded much valuable plunder."

It was agreed that another meeting should take place between Richard II and the leaders of the rebels at Smithfield on 15th June, 1381. William Walworth rode "over to the rebels and summoned Wat Tyler to meet the king, and mounted on a little pony, accompanied by only one attendant bearing the rebel banner, he obeyed". When he joined the king he put forward another list of demands that included: the removal of the lordship system, the distribution of the wealth of the church to the poor, a reduction in the number of bishops, and a guarantee that in future there would be no more villeins.

Richard II said he would do what he could. Wat Tyler was not satisfied by this reply. He called for a drink of water to rinse out his mouth. This was seen as extremely rude behaviour, especially as Tyler had not removed his hood when talking to the king. One of Richard's party shouted out that Tyler was "the greatest thief and robber in Kent". The author of the Anonimalle Chronicle of St Mary's claims: "For these words Wat wanted to strike the valet with his dagger, and would have killed him in the king's presence; but because he tried to do so, the Mayor of London, William of Walworth... arrested him... Wat stabbed the mayor with his dagger in the body in great anger. But, as it pleased God, the mayor was wearing armour and took no harm.. he struck back at the said Wat, giving him a deep cut in the neck, and then a great blow on the head. And during the scuffle a valet of the king's household drew his sword, and ran Wat two or three times through the body... Wat was carried by a group of the commons to the hospital for the poor near St Bartholomew's, and put to bed. The mayor went there and found him, and had him carried out to the middle of Smithfield, in the presence of his companions, and had him beheaded."

The peasants raised their weapons and for a moment it looked as though there was going to be fighting between the king's soldiers and the peasants. However, Richard rode over to them and said: "Will you shoot your king? I will be your chief and captain, you shall have from me that which you seek " He then spoke to them for some time and eventually they agreed to go back to their villages.

An army, led by Thomas of Woodstock, John of Gaunt's younger brother, was sent into Essex to crush the rebels. A battle between the peasants and the King's army took place near the village of Billericay on 28th June. The king's army was experienced and well-armed and the peasants were easily defeated. It is believed that over 500 peasants were killed during the battle. The remaining rebels fled to Colchester, where they tried in vain to persuade the towns-people to support them. They then fled to Huntingdon but the towns people there chased them off to Ramsey Abbey where twenty-five were slain.

King Richard with a large army began visiting the villages that had taken part in the rebellion. At each village, the people were told that no harm would come to them if they named the people in the village who had encouraged them to join the rebellion. Those people named as ringleaders were then executed. Apparently the king stated: "Serfs you are and serfs you will remain." A. L. Morton, the author of A People's History of England (1938) has pointed out: "The promises made by the king were repudiated and the common people of England learnt, not for the last time, how unwise it was to trust to the good faith of their rulers."

The king's officials were instructed to look out for John Ball. He was eventually caught in Coventry. He was taken to St Albans to stand trial. "He denied nothing, he freely admitted all the charges without regrets or apologies. He was proud to stand before them and testify to his revolutionary faith." He was sentenced to death, but William Courtenay, the Bishop of London, granted a two-day stay of execution in the hope that he could persuade Ball to repent of his treason and so save his soul. John Ball refused and he was hanged, drawn and quartered on 15th July, 1381.

On this day in 1536 Henry VIII marries Jane Seymour. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer issued a dispensation from prohibitions of affinity for Jane Seymour to marry Henry the day of the execution of Anne Boleyn, because they were fifth cousins. The couple were betrothed the following day, and a private marriage took place on 30th May 1536. Coming as it did after the death of Catherine of Aragon and the execution of Anne Boleyn, there could be no doubt of the lawfulness of Henry's marriage to Jane. The new queen was introduced at court in June. "No coronation followed the wedding, and plans for an autumn coronation were laid aside because of an outbreak of plague at Westminster; Jane's pregnancy undoubtedly eliminated any possibility of a later coronation."

Historians have claimed that Jane Seymour treated Henry's first daughter, Mary, with respect. "One of Jane's first requests of the King was that Mary be allowed to attend her, which Henry was pleased to allow. Mary was chosen to sit at the table opposite the King and Queen and to hand Jane her napkin at meals when she washed her hands. For one who had been banished to sit with the servants at Hatfield, this was an obvious sign of her restoration to the King's good graces. Jane was often seen walking hand-in-hand with Mary, making sure that they passed through the door together, a public acknowledgement that Mary was back in favour." In August, 1536 Ambassador Eustace Chapuys reported to King Charles V that "the treatment of the princess Mary is every day improving. She never did enjoy such liberty as she does now."

rJane Seymour gave birth to a boy on 12th October 1537 after a difficult labour that lasted two days and three nights. The child was named Edward, after his great-grandfather and because it was the eve of the Feast of St Edward. It was said that the King wept as he took the baby son in his arms. At the age of forty-six, he had achieved his dream. "God had spoken and blessed this marriage with an heir male, nearly thirty years after he had first embarked on matrimony."

Edward was christened when he was three days old, and both his sisters played a part in this important occasion. In the great procession which took the baby from the mother's bed-chamber to the chapel, Elizabeth carried the chrisom, the cloth in which the child was received after his immersion in the font. As she was only four years old, she herself was carried by the Queen's brother, Edward Seymour, the Earl of Hertford. Jane was well enough to receive guests after the christening. Edward was proclaimed prince of Wales, duke of Cornwall, and earl of Carnarvon.

On 17th October 1537 Jane became very ill. Most historians have assumed that she developed puerperal fever, something for which there was no effective treatment, though at the time the queen's attendants were blamed for allowing her to eat unsuitable food and to take cold. An alternative medical opinion suggests that Jane died because of retention of parts of the placenta in her uterus. That condition could have led to a haemorrhage several days after delivery of the child. What is certain is that septicaemia developed, and she became delirious. Jane died just before midnight on 24th October, aged twenty-eight.

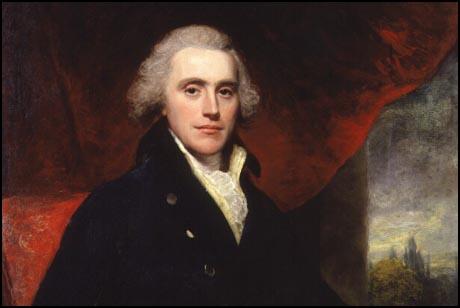

On this day in 1757 Henry Addington, was born. Henry's father, Dr. Anthony Addington, had several important patients including the prime minister, Lord Chatham and his son, William Pitt. After being educated at Winchester School and Oxford University he became a lawyer.

Addington's friendship with the Pitt family helped him obtain the seat for Devizes in 1784. Later that year, William Pitt, like his father before him, became prime minister of Britain. Henry Addington was a loyal supporter of Pitt's Tory administration. Although Addington was only thirty, in 1789 Pitt suggested that he should become speaker of the House of Commons. Addington agreed with the proposal and with the help of Pitt was elected as speaker. The post received a salary of £6,000 a year and this enabled Addington to purchase a large estate in Reading.

William Pitt's policy of Catholic Emancipation so upset King George III that he asked Addington to help him remove his prime minister. After discussing the matter with William Pitt, Addington agreed, and in 1801 he became Britain's new prime minister. Several ministers such as George Canning and Lord Castlereagh who agreed with Pitt's policy on Catholics, refused to serve under Addington. Henry Addington was an unpopular prime minister and in 1804 large numbers of his own party turned against him and he decided to resign.

The following year Addington was granted the title of Lord Sidmouth and agreed to serve as a minister in Pitt's government. However, he only served under William Pitt for six months. When Pitt refused to promote Viscount Sidmouth's friends he resigned from the cabinet.

In 1812 Lord Liverpool became prime minister and he offered Sidmouth the post of Home Secretary in his new government. Viscount Sidmouth now had the responsibility of dealing with social unrest in Britain. This included making machine-breaking an offence punishable by death. On one day alone, fourteen Luddites were executed in York. Social unrest continued and in 1817, Sidmouth was responsible for the passing of what became known as the Gagging Acts. This resulted in the arrest and imprisonment of radical journalists such as Richard Carlile.

The unpopularity of Sidmouth increased in 1819 after he wrote a letter supporting the action of the magistrates and the Manchester & Salford Yeomanry at what opponents called the Peterloo Massacre. In November 1819, Sidmouth persuaded Parliament to pass a series of repressive measures that became known as the Six Acts. Sidmouth retired from office in 1821. He continued to support the Tories in parliament and voted against Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the Reform Act of 1832. Lord Sidmouth died on 15th February 1844.

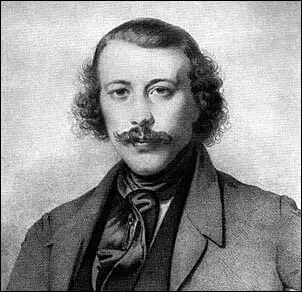

On this day in 1814 Russian philosopher, Mikhail Bakunin was born in Premukhino, Russia. The eldest son of a landowner he entered the Imperial Russian Artillery School at the age of fourteen.

Bakunin became an army officer in 1833 but after being sent to the Polish frontier he resigned his commission and began studying philosophy. As a young man he met and was deeply influenced by the radical philosopher, Alexander Herzen. He was impressed with Bakunin and later commented: "This man was born not under an ordinary star but under a comet."

Bakunin left Russia in 1842 and lived in Dresden before moving to Paris where he met Karl Marx. He participated in the 1848 French Revolution and then moved to Germany where he called for the overthrow of the Habsburg Empire. The composer, Richard Wagner met him during this period and later pointed out: "Everything about him was colossal and he was full of a primitive exuberance and strength." His biographer, Paul Avrich, added: "His broad magnanimity and childlike enthusiasm, his burning passion for liberty and equality, and his volcanic onslaughts against privilege and injustice all gave him enormous appeal in the libertarian circles of his day."

During the Dresden Insurrection in May, 1849, Bakunin was arrested and sentenced to death. He was reprieved and extradited to Austria where he was wanted for his role in the Czech Republic Revolt. He was once again found guilty and sentenced to death. This was eventually commuted and in 1851 he was passed on to the Russian government and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress in St. Petersburg. In 1854 he was transferred to to the Shlisselburg Fortress and stayed there until 1857 when he was exiled to Siberia.

In 1861 Bakunin managed to escape from Tomsk and reached Japan on 16th August. Paul Avrich has argued: "Despite his years of confinement, he still possessed much of his old vitality and exuberance. He had aged, to be sure, had lost his teeth from scurvy and grown quite fat. But the grey-blue eyes retained their penetrating brilliance; and his voice, eloquence, and physical bulk combined to make him the center of attention."

In September 1861, Bukunin arrived in San Francisco. Over the next few weeks he visited New York City and Boston, where he met John Andrew, George B. McClellan, Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson. Over the next few weeks he mixed with Radical Republicans. He wrote to his friend, Alexander Herzen, that he was very interested in the American Civil War and that "my sympathies are all with the North".

Bakunin also visited his old friend, Louis Agassiz. He introduced him to Henry Longfellow. That night he recorded in his diary: "George Sumner and Mikhail Bakunin to dinner. Mr. Bakunin is a Russian gentleman of education and ability - a giant of a man, with a most ardent, seething temperament. He was in the Revolution of Forty-eight; has seen the inside of prisons of Olmiitz, even, where he had Lafayette's room. Was afterwards four years in Siberia; whence he escaped in June last, down the Amoor, and then in an American vessel by way of Japan to California, and across the isthmus, hitherward. An interesting man." Annie, Longfellow's daughter added that Bukunin was a "big creature with a big head, wild bushy hair, big eyes, big mouth, a big voice and still bigger laugh."

Mikhail Bakunin enjoyed his time in America, claiming that "the most imperfect republic is a thousand times better than the most enlightened monarchy". He added that the United States and Britain were the "only two great countries" where the people possessed genuine "liberty and political power" where even "the most disinherited and miserable foreigners".

Bakunin eventually reached London where he joined his old friend, Alexander Herzen. The two men worked together on the journal, The Bell, until 1863 when Bakunin went to join the insurrection in Poland. However, he failed to reach his destination and after a spell in Sweden he moved to Italy before settling in Geneva in 1868.

Bakunin had a great influence on radical young students in Russia. In March 1869 he met Sergi Nechayev Soon afterwards Bakunin wrote to James Guillaume that: "I have here with me one of those young fanatics who know no doubts, who fear nothing, and who realize that many of them will perish at the hands of the government but who nevertheless have decided that they will not relent until the people rise. They are magnificent, these young fanatics, believers without God, heroes without rhetoric."

In 1869 he co-wrote Catechism of a Revolutionist with Sergi Nechayev. It included the famous passage: "The Revolutionist is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion - the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose - to destroy it."

In August, 1869, Nechayev returned to Russia and settled in Moscow where he set up a secret terrorist organization, People's Retribution. When one of its members, Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov, questioned Nechayev's political ideas, he murdered him. The body was weighted down with stones and dumped through an ice hole in a nearby pond. He told the rest of the group, "the ends justify the means".

Sergi Nechayev escaped from Moscow but after discovering the body, some three hundred revolutionaries were arrested and imprisoned. Nechayev arrived in Locarno, where Mikhail Bakunin was living, in January 1870. At first Bakunin was pleased to see Nechayev but the relationship soon deteriorated. According to Z.K. Ralli, Nechayev no longer showed any deference to his mentor. Nechayev told friends that Bakunin had lost the "level of energy and self-abnegation" required to be a true revolutionary. Bakunin wrote that: "If you introduce him to a friend, he will immediately proceed to sow dissension, scandal, and intrigue between you and your friend and make you quarrel. If your friend has a wife or a daughter, he will try to seduce her and get her with child in order to snatch her from the power of conventional morality and plunge her despite herself into revolutionary protest against society."

German Lopatin arrived from Russia with news that it was Nechayev was responsible for the murder of Ivan Ivanovich Ivanov. Mikhail Bakunin wrote to Sergi Nechayev: "I had complete faith in you, while you duped me. I turned out to be a complete fool. This is painful and shameful for a man of my experience and age. Worse than this, I spoilt my situation with regard to the Russian and International causes."

Bakunin completely disagreed with Nechayev's approach to anarchism which he called his "false Jesuit system". He argued that the popular revolution must be "invisibly led, not by an official dictatorship, but by a nameless and collective one, composed of those in favour of total people's liberation from all oppression, firmly united in a secret society and always and everywhere acting in support of a common aim and in accordance with a common program." He added: "The true revolutionary organization does not foist upon the people any new regulations, orders, styles of life, but merely unleashes their will and gives wide scope to their self-determination and their economic and social organization, which must be created by themselves from below and not from above.... The revolutionary organization must make impossible after the popular victory the establishment of any state power over the people - even the most revolutionary, even your power - because any power, whatever it calls itself, would inevitably subject the people to old slavery in new form."

Mikhail Bakunin told Sergi Nechayev: "You are a passionate and dedicated man. This is your strength, your valor, and your justification. If you alter your methods, I would wish not only to remain allied with you, but to make this union even closer and firmer." He wrote to N. P. Ogarev that: "The main thing for the moment is to save our erring and confused friend. In spite of all, he remains a valuable man, and there are few valuable men in the world.... We love him, we believe in him, we foresee that his future activity will be of immense benefit to the people. That is why we must divert him from his false and disastrous path."

Bakunin joined the International Working Men's Association (the First International), a federation of radical political parties that hoped to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist commonwealth. Bakunin had several disagreements with Karl Marx, the other prominent figure in the organization. Bakunin opposed Marx's ideas on state socialism, claiming that it would replace one oppressive form of government with another. Bakunin argued: "No theory, no ready-made system, no book that has ever been written will save the world. I cleave to no system."

Peter Lavrov was another member who disagreed with Bakunin about the way change will be achieved. In 1873 Lavrov argued: "The reconstruction of Russian society must be achieved not only for the sake of the people, but also through the people. But the masses are not yet ready for such reconstruction. Therefore the triumph of our ideas cannot be achieved at once, but requires preparation and clear understanding of what is possible at the given moment."

Bakunin was accused of anarchism and in 1872 he was expelled from the First International. The following year Bakunin published his major work, Statism and Anarchy. In the book Bakunin advocated the abolition of hereditary property, equality for women and free education for all children. He also argued for the transfer of land to agricultural communities and factories to labour associations.

Over the last few years of life, Bakunin continued to be active in politics, hoping that he would help to create a world revolution that would enable an international federation of autonomous communities to be created.

Mikhail Bakunin died in Berne, Switzerland, on 1st July, 1876.

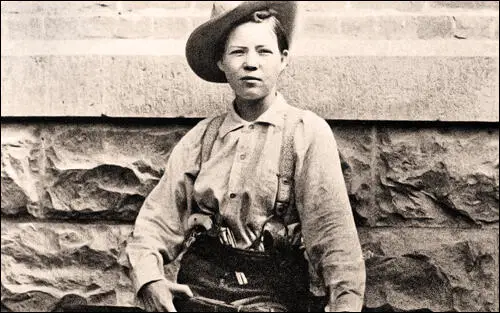

On this day in 1899 Pearl Hart, robs a stage coach 30 miles southeast of Globe, Arizona. Pearl Taylor was born in Lindsay, Ontario in 1871. At the age of seventeen she married a man named Brett Hart. The marriage was unhappy and Pearl Hart decided to leave her husband.

In 1892 she arrived in Phoenix, Arizona. Her husband eventually found her and they continued their stormy relationship until he joined the army. Pearl now become a cook in a mining camp. In 1898 Pearl Hart and a miner, Joe Boot, robbed the Globe to Florence stagecoach. Research suggests this was the last stagecoach robbery in American history. Hart and Boot managed to obtain $431 but they were captured three days later. Hart was sentenced to five years. However, Boot got 35 years.

Hart was the first woman to be sent to Yuma Territorial Prison. In 1901 it was discovered that Hart was pregnant. This caused a serious problem as the only two men who had been alone with her was a church minister and the Governor of Arizona, Alexander Brodie. To avoid a scandal the prison authorities decided to release Hart from prison.

After the birth of her child Hart worked as a prostitute. 1904 she was again arrested at Deming, New Mexico, on suspicion of being involved in a train robbery but was eventually released for lack of evidence. Hart then performed with the Wild West Show before marrying a rancher in Arizona. It is believed that Pearl Hart died in about 1960.

On this day in 1914 Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks are found guilty of arson. In July 1912, Emmeline Pankhurst gave permission for Christabel Pankhurst, to launch a secret arson campaign. She knew that she was likely to be arrested and so she decided to move to Paris. Attempts were made by suffragettes to burn down the houses of two members of the government who opposed women having the vote. These attempts failed but soon afterwards, a house being built for David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was badly damaged by suffragettes.

As Fern Riddell has pointed out: "From 1912 to 1914, Christabel Pankhurst orchestrated a nationwide bombing and arson campaign the likes of which Britain had never seen before and hasn't experienced since. Hundreds of attacks by either bombs or fire, carried out by women using codenames and aliases, destroyed timber yards, cotton mills, railway stations, MPs' homes, mansions, racecourses, sporting pavilions, churches, glasshouses, even Edinburgh's Royal Observatory. Chemical attacks on postmen, postboxes, golfing greens and even the prime minister - whenever a suffragette could get close enough - left victims with terrible burns and sorely irritated eyes and throats, and destroyed precious correspondence."

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. During the trial, Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone." It has speculated that this group included Hilda Burkitt, Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Lilian Lenton, Mary Richardson, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Olive Wharry and Florence Tunks.

Hilda Burkitt's first partner was Clara Giveen. On 25th November 1913 Hilda was arrested with Clara Giveen for attempting to set fire to the grandstand at the Headingley Football Ground the property of The Leeds Cricket, Football and Athletic Company. The Yorkshire Evening Post reported that Clara Giveen had "escaped from the supervision of the police in Birmingham, to which town she went on Saturday, just before the expiration of her licence."

Hilda went on the run before joining up with Florence Tunks, a 22 year old bookkeeper in Cardiff, to carry out a series of arson attacks. On 11th April 1914 they arrived in Suffolk for two weeks of arson. "They then moved through Suffolk, riding bicycles across the countryside and leaving phosphorus in haystacks, which would combust a day or so after they had left."

On 17th April they bombed the Britannia Pavilion on the pier in Great Yarmouth had been reduced to "a shapeless mass of twisted girders and charred woodwork." The owner of the Pavilion received a letter bearing one word, "Retribution", and a "Votes for Women" postcard was found on the sands with comments about Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary: "Mr McKenna has nearly killed Mrs Pankhurst. We can show no mercy until women are enfranchised."

Burkitt and Tunks then travelled to Felixstowe where they took a room at Mayflower Cottage, the home of Daisy Meadows, whose father, George Meadows, was a bathing-machine proprietor. Daisy remembered the woman arriving with six cases of luggage and a bicycle. Two days later they said they were going to the theatre in Ipswich. Daisy said in court: "I didn't see them go out and didn't see them again until about five minutes to nine next morning."

Instead of going to the theatre, Burkitt and Tunks, had carried out an arson attack on the Bath Hotel, the oldest in the town. The hotel had been built in 1839 at a time when planners were attempting to establish the Suffolk town as a spa resort. No-one was in the hotel at the time of the fire as it was closed for the season. The cost of the damage was £35,000, estimated to be the equivalent of £2.6m today. They left a few clues: labels on the bushes saying "votes for women" and there was a banner that said "there will be no peace until women get the vote."

George Meadows was near the Bath Hotel when it was set on fire. He saw "two ladies there who were laughing, one was tall and the other short." He identified them as Burkitt and Tunks and they were arrested the next morning at Mayflower Cottage. The police searched their rooms before taking them into custody. They found two boxes of matches, four candles, a glazier's diamond, four copies of The Suffragette newspaper, a lamp, a hammer and pliers."

On 26 May 1914 Burkitt and Tunks were charged with "feloniously, unlawfully and maliciously" setting fire to two wheat stacks at Bucklesham Farm, worth £340 on 24 April; destroying a stack, worth £485 on 24 April at Levington; and setting fire to the Bath Hotel in Felixstowe, on 28 April. The women refused to answer any questions in court, sat on a table with their backs to the magistrate, and chatted while the evidence against them was presented.

During their trial at Suffolk Assizes the women refused to behave in the appropriate manner. The clerk was reading the the indictment when Burkitt shouted out, "Speak up, please, I can't hear." Asked to plead she replied "I don't recognise the jurisdiction of the Court at all. I don't recognize the Judge, or any of these men." While the Jury were being sworn Burkitt shouted "I object to all these men on the jury." Both women "giggled" and loudly laughed, and cried "No surrender." Tunks commented I don't recognize the Court at all.turned her back to the Court". Tunks turned her back to the Court, but was forcibly brought back by the wardresses. Burkitt shouted: "I am not going to keep quiet: I have come here to enjoy myself. I object to the whole of the jury. I am not going to listen to anything you have got to say."

Richard White, a commander in the Royal Navy, gave evidence that he had been standing outside the Bath Hotel at ten o'clock, just hours before the fire broke out. "I had my suspicions aroused... I knew that suffragettes were about. I had it at the back of my mind that probably that's what they might be." Hilda shouted abuse at Commander White, accusing him of trying to seduce them and threw her shoes at White.

On 29th May, 1914, Hilda Burkitt was sentenced to two years' imprisonment, and Florence Tunks to nine months. Hilda told the judge to put on his black cap "and pass sentence of death or not waste his breath". Tunks "vowed that she would be out of prison before long, and that victory would be hers." (30) In prison she was force-fed 292 times.

On this day in 1915 Vera Brittain writes letter to Roland Leighton on the subject of conscription. "A more than usually heated conflict is going on in the papers about the war in general and conscription in particular. Lord Northcliffe's papers seem to be attacking anyone in authority, especially Lord Kitchener, and the rest of the press is attacking Lord Northcliffe. If the subjects of their controversy were not so immense and terrible it would be quite amusing, but as it is it seems a dreadful state of affairs that the authorities are quarrelling among themselves at home while men who are in their hands are dying for them abroad... What do you think about conscription yourself? I think men at the front must surely know more about it than the squabblers in the Cabinet. Edward is very much against it; he says it would to a great extent destroy the morale of our army, which is the chief factor in rendering it superior to other armies in general."

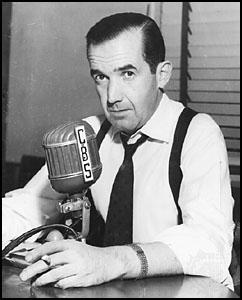

On this day in 1940 Edward Murrow, CBS radio broadcast from London, reports on Dunkirk.

The battle around Dunkirk is still raging. The city itself is held by marines and covered by naval guns. The British Expeditionary Force has continued to fall back toward the coast and part of it, included wounded and those not immediately engaged, has been evacuated by sea. Certain units, the strength of which is naturally not stated, are back in England.

On the home front, new defence measures are being announced almost hourly. Any newspaper opposing the prosecution of the war can now be suppressed. Neutral vessels arriving in British ports are being carefully searched for concealed troops. Refugees arriving from the Continent are being closely questioned in an effort to weed out spies. More restrictions on home consumption and increased taxation are expected. Signposts are being taken down on the roads that might be used by German forces invading this country. Upon hearing about the signposts, an English friend of mine remarked, "That's going to make a fine shumuzzle. The Germans drive on the right and we drive on the left. There'll be a jolly old mix-up on the roads if the Germans do come."

One of the afternoon papers finds space to print a cartoon showing an elderly aristocratic Englishman, dressed in his anti-parachute uniform, saying to his servant, who holds a double-barrel shotgun, "Come along, Thompson. I shall want you to load for me." The Londoners are doing their best to preserve their sense of humour, but I saw more grave solemn faces today than I have ever seen in London before.

Fashionable tearooms were almost deserted; the shops in Bond Street were doing very little business; people read their newspapers as they walked slowly along the streets. Even the newsreel theatres were nearly empty. I saw one woman standing in line waiting for a bus begin to cry, very quietly. She didn't even bother to wipe the tears away. In Regent Street there was a sandwich man. His sign in big red letters had only three words on it: WATCH AND PRAY.

On this day in 1942 Air Marshall Arthur Harris orders the bombing of Cologne. In February, 1942, Arthur Harris became head of RAF Bomber Command. His brief was "to focus attacks on the morale of the enemy civil population, and in particular, of the industrial workers". According to Richard K. Morris: "During March and April he had begun to experiment with attacks which concentrated bombers in time and space, to engulf radar-controlled flak and fighters, and overwhelm a city's fire-services. The force inherited by Harris was nevertheless too small to do this on any scale, and his efforts to increase it were being sapped both by losses and what he called the robbery of trained crews by other commands. To make his case, Harris decided to gamble Bomber Command's reserves in an attack of unprecedented weight: a thousand aircraft against a single objective."

As Harris later pointed out: "The organization of such a force - about twice as great as any the Luftwaffe ever sent against this country - was no mean task in 1942. As the number of first-line aircraft in squadrons was quite inadequate, the training organization.... We made our preparations for the thousand bomber attack during May." It was given the code word "Millenium". More than a third of his force was composed of instructors and trainees. Heavy losses among them would have a "paralysing effect" on Bomber Command's future.

On 20th May, 1942, notified his group commanders of the plan and all leave was cancelled. Harris decided that the target should be Cologne. "The organisation of the force involved a tremendous amount of work throughout the Command. The training units put up 366 aircraft. No. 3 Group, with its conversion units put up about 250 aircraft, which was at that time regarded as a strong force in itself. Apart from four aircraft of Flying Training Command, the whole force of 1047 aircraft was provided by Bomber Command.... Nearly 900 aircraft attacked out of the total of 1047, and within an hour and a half dropped 1455 tons of bombs, two thirds of the whole load being incendiaries."

Leonard Cheshire, one of the pilots involved in the attack, explained in his book, Bomber Pilot (1943): "I glued my eyes on the fire and watched it grow slowly larger. Of ack-ack there was not much, but the sky was filled with fighters.... Already, only twenty-three minutes after the attack had started, Cologne was ablaze from end to end, and the main force of the attack was still to come. I looked at the other bombers, I looked at the row of selector switches in the bomb compartment, and I felt, perhaps, a slight chill in my heart. But the chill did not stay long: I saw other visions, visions of rape and murder and torture. And somewhere in the carpet of greyish-mauve was a tall, blue-eyed figure waiting behind barbed-wire' walls for someone to bring him home. No, the chill did not last long.... I felt a curious happiness inside my heart. For the first time in history the emphasis of night bombing had passed out of the hands of the pilots and into the hands of the organizers, and the organizers had proved their worth. In spite of the ridicule of some of their critics, they have proved their worth. They have proved, too, beyond any shadow of doubt that given the time the bomber can win the war. Not only have they proved it, they have written the proof on every face that saw Cologne."

Harris explained in Bomber Command (1947): "The casualty rate was 3.3 per cent, with 39 aircraft missing, and, in spite of the fact that a large part of the force consisted of semi-trained crews and that many more fighters were airborne than usual, this was considerably less than the average 4.6 per cent for operations in similar weather during the previous twelve months. The medium bomber had a casualty rate of 4.5 per cent, which was remarkable, but it was still more remarkable that we lost scarcely any of the 300 heavy bombers that took part in this operation; the casualty rate for the heavies was only 1.9 per cent. These had attacked after the medium bombers, when the defences had been to some extent beaten down, and in greater concentration than was possible for the new crews in the medium bombers. The figures proved conclusively that the enemy's fighters and flak had been effectively saturated; an analysis of all reports on the attack showed that the enemy's radar location devices had been able to pick up single aircraft and follow them throughout the attack, but that the guns had been unable to engage more than a small proportion of the large concentration of aircraft."

Konrad Adenauer, the mayor of Cologne, pointed out: "The task confronting me in a war-ravaged Cologne was a huge and extra-ordinarily difficult one. The extent of the damage suffered by the city in air raids and from the other effects of war was enormous. More than half of the houses and public buildings were totally destroyed, nearly all the others had suffered partial damage. Only 300 houses had escaped unscathed. The damage done to the city by the destruction of streets, tram rails, sewers, water pipes, gas pipes, electrical installations and other public utilities, was no less widespread. It is hard to realize the threat this constituted to the health of the people. There was no gas, no water, no electric current, and no means of transport. The bridges across the Rhine had been destroyed. There were mountains of rubble in the streets. Everywhere there were gigantic areas of debris from bombed and shelled buildings. With its razed churches, many of them almost a thousand years old, its bombed-out cathedral, with the ruins of once beautiful bridges sticking up out of the Rhine, and the vast expanses of derelict houses, Cologne was a ghost city."