On this day on 18th February

On this day in 1516 Mary Tudor, the daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon was born at Greenwich Palace. Henry gave Mary "unusually close attention during her early years because she was the only survivor of Catherine's many pregnancies and because the pretty and precocious child obviously delighted both parents". However, It was very important to Henry that his wife should give birth to a male child. Without a son to take over from him when he died, Henry feared that the Tudor family would lose control of England.

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. The following day Edward and his thirteen year-old sister, Elizabeth, were informed that their father had died. According to one source, "Edward and his sister clung to each other, sobbing". Edward VI's coronation took place on Sunday 20th February. "Walking beneath a canopy of crimson silk and cloth of gold topped by silver bells, the boy-king wore a crimson satin robe trimmed with gold silk lace costing £118 16s. 8d. and a pair of ‘Sabatons’ of cloth of gold."

Edward was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist Edward VI in governing his new realm. It was not long before his uncle, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. Thomas Seymour (Lord Sudeley) was furious that his brother had risen so far so fast. To increase his power he secretly married Edward's stepmother, Catherine Parr. Edward wrote in his journal: "The Lord Seymour of Sudeley married the Queen, whose name was Catherine, with which marriage the Lord Protector was much offended."

The Duke of Somerset was a Protestant and he soon began to make changes to the Church of England. This included the introduction of an English Prayer Book and the decision to allow members of the clergy to get married. Attempts were made to destroy those aspects of religion that were associated with the Catholic Church, for example, the removal of stained-glass windows in churches and the destruction of religious wall-paintings. Somerset made sure that Edward VI was educated as a Protestant, as he hoped that when he was old enough to rule he would continue the policy of supporting the Protestant religion.

Somerset's programme of religious reformation was accompanied by bold measures of political, social, and agrarian reform. Legislation in 1547 abolished all the treasons and felonies created under Henry VIII and did away with existing legislation against heresy. Two witnesses were required for proof of treason instead of only one. Although the measure received support in the House of Commons, its passage contributed to Somerset's reputation for what later historians perceived as his liberalism.

King Edward VI died on 6th July, 1553. Three days later one of Northumberland's daughters came to take Lady Jane Grey to Syon House, where she was ceremoniously informed that the king had indeed nominated her to succeed him. Jane was apparently "stupefied and troubled" by the news, falling to the ground weeping and declaring her "insufficiency", but at the same time praying that if what was given to her was "‘rightfully and lawfully hers", God would grant her grace to govern the realm to his glory and service.

On 10th July, Queen Jane arrived in London. An Italian spectator, witnessing her arrival, commented: "She is very short and thin, but prettily shaped and graceful. She has small features and a well-made nose, the mouth flexible and the lips red. The eyebrows are arched and darker than her hair, which is nearly red. Her eyes are sparkling and reddish brown in colour." (64) Guildford Dudley, "a tall strong boy with light hair’, walked beside her, but Jane apparently refused to make him king, saying that "the crown was not a plaything for boys and girls."

Jane was proclaimed queen at the Cross in Cheapside, a letter announcing her accession was circulated to the lords lieutenant of the counties, and Bishop Nicolas Ridley of London preached a sermon in her favour at Paul's Cross, denouncing both Mary and Elizabeth as bastards, but Mary especially as a papist who would bring foreigners into the country. It was only at this point that Jane realised that she was "deceived by the Duke of Northumberland and the council and ill-treated by my husband and his mother".

Mary, who had been warned of what John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, had done and instead of going to London as requested, she fled to Kenninghall in Norfolk. As Ann Weikel has pointed out: "Both the earl of Bath and Huddleston joined Mary while others rallied the conservative gentry of Norfolk and Suffolk. Men like Sir Henry Bedingfield arrived with troops or money as soon as they heard the news, and as she moved to the more secure fortress at Framlingham, Suffolk, local magnates like Sir Thomas Cornwallis, who had hesitated at first, also joined her forces."

Mary summoned the nobility and gentry to support her claim to the throne. Richard Rex argues that this development had consequences for her sister, Elizabeth: "Once it was clear which way the wind was blowing, she (Elizabeth) gave every indication of endorsing her sister's claim to the throne. Self-interest dictated her policy, for Mary's claim rested on the same basis as her own, the Act of Succession of 1544. It is unlikely that Elizabeth could have outmanoeuvred Northumberland if Mary had failed to overcome him. It was her good fortune that Mary, in vindicating her own claim to the throne, also safeguarded Elizabeth's."

The problem for Dudley was that the vast majority of the English people still saw themselves as "Catholic in religious feeling; and a very great majority were certainly unwilling to see - King Henry's eldest daughter lose her birthright." When most of Dudley's troops deserted he surrendered at Cambridge on 23rd July, along with his sons and a few friends, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London two days later. Tried for high treason on 18th August he claimed to have done nothing save by the king's command and the privy council's consent. Mary had him executed at Tower Hill on 22nd August. In his final speech he warned the crowd to remain loyal to the Catholic Church.

As soon as she gained power, Queen Mary ordered the release of the Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, Bishop Stephen Gardiner and Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall and other Catholic prisoners from the Tower of London. "Raising them up one by one, she kissed them and granted them their liberty." Norfolk was restored to his rank and estates. However, he was in a poor state of health and one contemporary commented "by long imprisonment diswanted from the knowledge of our malicious World".

Queen Mary told a foreign ambassador that her conscience would not allow her to have Lady Jane Grey put to death. Jane was given comfortable quarters in the house of a gentleman gaoler. The anonymous author of the Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary (c. 1554), dropped in for dinner, finding the Lady Jane sitting in the place of honour. She made the visitor welcome and asked for news of the outside world, before going on to speak gratefully of Mary - "I beseech God she may long continue" and made a fierce attack against John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland: "Woe worth him! He hath brought me and our stock in most miserable calamity by his exceeding ambition".

Jane, together with Guildford Dudley and two more of his brothers, stood trial for treason on 19th November. They were all found guilty but foreign ambassadors in London reported that Jane's life would be spared. Mary's attitude towards Jane changed when her father, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, joined the rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt against her proposed marriage to Philip of Spain. Based at Rochester Castle, Wyatt soon had fifteen hundred men under his command.

Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, aged 80, agreed to lead the Queen's army against the rising led by Wyatt. As David Loades, the author of Mary Tudor (2012), pointed out "that venerable warrior, the Duke of Norfolk, set out from London with a hastily assembled force to confront what was now clearly a rebellion". Unfortunately, most of Norfolk's troops consisted of the London militia, who were strongly sympathetic to Wyatt. On the 29th January, 1554, they deserted in large numbers, and Norfolk was forced to retreat with the soldiers who were left.

When Mary heard about Wyatt's actions, she issued a pardon to his followers if they returned to their homes within twenty-four hours. Some of his men took up the offer. However, when a large number of the army were sent to arrest Wyatt, they changed sides. Wyatt now controlled a force of 4,000 men and he now felt strong enough to march on London.

On 1st February, 1554, Mary addressed a meeting in the Guildhall where she proclaimed Wyatt a traitor. The next morning, 20,000 men enrolled their names for the protection of the city. The bridges over the Thames within a distance of fifteen miles were broken down and on 3rd February, a reward of land of the annual value of one hundred pounds a year was offered to the person who captured Wyatt.

By the time Thomas Wyatt entered Southwark, large numbers of his army had deserted. However, he continued to march towards St. James's Palace, where Mary Tudor had taken refuge. Wyatt reached Ludgate at two o'clock in the morning of 8th February. The gate was shut against him, and he was unable to break it down. Wyatt now went into retreat but he was captured at Temple Bar.

Although there is not any evidence that Jane had any foreknowledge of the conspiracy, "her very existence as a possible figurehead for protestant discontent made her an unacceptable danger to the state". Mary, now agreed with her advisers and the date of Jane's execution was fixed for 9th February, 1554. However, she was still willing to forgive Jane and sent John Feckenham, the new dean of St Paul's, over to the Tower of London in an attempt to see if he could convert this "obdurate heretic". However, she refused to change her Protestant beliefs.

Jane watched the execution of her husband from the window of her room in the Tower of London. She then came out leaning on the arm of Sir John Brydges, Lieutenant of the Tower. "Lady Jane was calm, although, Elizabeth and Ellen (her two women attendants) wept... The executioner kneeled down and asked for forgiveness, which she gave most willingly... she said: "I pray you dispatch me quickly."

According to the Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary: "Then she kneeled down, saying, 'Will you take it off before I lay me down?' and the hangman answered her, 'No, madame.' She tied the kercher about her eyes; then feeling for the block said, 'What shall I do? Where is it?' One of the standers-by guiding her thereto, she laid her head down upon the block, and stretched forth her body and said: 'Lord, into thy hands I commend my spirit!' And so she ended."

Stories circulated as to the piety and dignity on the scaffold, however, she did not receive a great deal of sympathy. (81) As Alison Plowden has pointed out: "The judicial murder of sixteen-year-old Jane Grey, and no one ever pretended it was anything else, caused no great stir at the time, not even among the militantly protestant Londoners. Jane had never been a well-known figure, and in any case was too closely associated with the unpopular Dudleys and their failed coup to command much public sympathy."

At the time Mary became Queen she was thirty-seven, small in stature and near-sighted, appeared older than her years and often tired, because of her generally poor health. Her first parliament reinforced the Act of Succession of 1543 by declaring the validity of the marriage of her mother, Catherine of Aragon, so that the issue of "Mary's legitimacy could not be associated with the abolition of the royal supremacy and the restoration of papal authority."

Almost from her infancy Mary had "hawked around Europe and offered to every prince from Portugal to Poland". As she had been described by her own father as illegitimate, she did not obtain a husband. She felt humiliated and now she was Queen of England, she had much more to offer. Mary also needed an heir. The Protestant attempts to overthrow Mary had also made her feel insecure. To protect her position, Mary decided to form an alliance with the Catholic monarchy in Spain. This gave her the "prospect of a Catholic heir, reunion with Rome, her martyred mother's Spanish dynasty."

Mary was the first woman to rule England in her own right. It soon became clear that Mary was not going to be ruled by her Privy Council. Her first move was to put her marriage into the hands of her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Therefore her councillors found that Mary had excluded them from the marital decision-making process. This is something that no previous king had done.

Charles V, with little concern for Mary, seized the opportunity to increase his influence over England by proposing his son Philip II as her husband. According to Simon Renard, the Spanish ambassador, Mary disliked the idea and reached the decision with the greatest reluctance. "She was disgusted at the idea of having sex with a man; but the Emperor and his ambassador were strongly in favour of a marriage which would unite England with the Emperor's territories in a permanent alliance." This move was opposed by Bishop Stephen Gardiner, her Lord Chancellor, who wanted her to marry Edward Courtenay, a man he thought was more acceptable to the English people.

Mary was determined to produce an heir, thus preventing her sister, Elizabeth, a Protestant, from succeeding to the throne. In negotiations it was agreed that Philip was to be styled "King of England", but he could not act without his wife's consent or appoint foreigners to office in England. Philip was unhappy at the conditions imposed, but he was ready to agree for the sake of securing the marriage.

Philip arrived in England on 19th July, 1554. Their first meeting turned out fairly well in spite of the obvious age difference (Mary was 38 and Philip was 27). The ceremony took place at Winchester Cathedral on 25th July 1554, two days after their first meeting. Mary taught Philip to say "Good night my lords and ladies" in English but this was probably the limit of his proficiency in the language. He spent little time in England and was alleged to have several mistresses in Spain. "Whether he was really as promiscuous as alleged, we do not know, but it is unlikely in view of his rigid piety. On the other hand a man who very seldom saw his wife could well keep a mistress - or a succession of mistresses - without ever feeling called upon to acknowledge the fact."

Soon rumours began circulating that Mary was pregnant. In April 1555, Elizabeth, who was held under house arrest, was summoned to Court to witness the birth of the expected child that summer. However, no child was forthcoming and Mary still did not have an heir.

In deciding to marry Philip of Spain, the only son of Emperor Charles V, Mary made her first and most serious political error. "She either failed to comprehend or chose to disregard the depth of an English xenophobic sentiment which was made all the more powerful for being combined with anxiety about the potential power of a male consort. The prospect of a foreign ruler created considerable opposition in parliament and throughout the realm." When the speaker of the House of Commons suggested she marry an English subject, not a foreign prince, Mary angrily told him that she would not subject herself in marriage to an individual whom her position made her inferior.

Mary appointed Bishop Stephen Gardiner as her Lord Chancellor. He had been imprisoned during the reign of Edward VI. Over the next two years Gardiner attempted to restore Catholicism in England. In the first Parliament held after Mary gained power most of the religious legislation of Edward's reign was repealed.

In November 1554, Mary's distant cousin, Reginald Pole, returned from exile, to become Archbishop of Canterbury. He shared Mary's devotion to the Catholic Church and wished to see England restored to full communion with Rome. Pole and Gardiner persuaded Parliament to revive former measures against heresy. These had been repealed under Henry VIII and Edward VI.

In early 1555 Lord Chancellor Stephen Gardiner took part in the trials and examinations of John Hooper, Rowland Taylor, John Rogers, and Robert Ferrar, all of whom were burnt. He was also present in the summer of 1555 at meetings of the privy council which approved the execution of heretics. David Loades claims that "the threat of fire would send all these rats scurrying for cover, and when his bluff was called, he was taken aback." Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of Durham, participated to some degree in the trials of notable protestants, he condemned no one to death and seems to have been on the whole unconvinced by the policy of persecution.

Thomas Cranmer had been Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Edward VI. As soon as Mary gained power she ordered the arrest of Cranmer and he was questioned about the Lady Jane Grey coup. He was arrested on 13th November, on charges of joining with John Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland, to seize power. At his trial for treason he admitted that he "confessed more… than was true". Found guilty, his household was broken up, much of his goods sold off and most of his protestant books apparently destroyed.

Cranmer, Nicolas Ridley, John Bradford, and Hugh Latimer were taken to Oxford to stand trial for heresy. Bradford was executed on 1st July, 1555. At his trial on 12th September, Cranmer made the distinction between obedience that he owed to the crown and his complete rejection of the pope. After this a string of witnesses appeared who confirmed that Cranmer was the symbol of everything that had changed in the church between 1533 and 1553. On 16th October, Cranmer was forced to watch his friends, Ridley and Latimer, burnt at the stake.

On 24th February, 1556, a writ was issued ordering the execution of Cranmer. Two days later Cranmer issued a statement that was truly a recantation of his religious beliefs. When this did not bring a reprieve, he issued a further statement on 18th March. Diarmaid MacCulloch makes the point: "It is worth noting that he signed this when there was no possibility of his being pardoned and spared. What happened next, his dramatic reversal of his recantation, was therefore not simply an act of spite by a desperate man who felt that he had nothing to lose by defying the regime and the old church."

On 21st March, 1556, Thomas Cranmer he was brought to St Mary's Church in Oxford, where he stood on a platform as a sermon was directed against him. He was then expected to deliver a short address in which he would repeat his acceptance of the truths of the Catholic Church. Instead he proceeded to recant his recantations and deny the six statements he had previously made and described the Pope as "Christ's enemy, and Antichrist, with all his false doctrine." The officials pulled him down from the platform and dragged him towards the scaffold.

Cranmer had said in the Church that he regretted the signing of the recantations and claimed that "since my hand offended, it will be punished... when I come to the fire, it first will be burned." According to John Foxe: "When he came to the place where Hugh Latimer and Ridley had been burned before him, Cranmer knelt down briefly to pray then undressed to his shirt, which hung down to his bare feet. His head, once he took off his caps, was so bare there wasn't a hair on it. His beard was long and thick, covering his face, which was so grave it moved both his friends and enemies. As the fire approached him, Cranmer put his right hand into the flames, keeping it there until everyone could see it burned before his body was touched." Cranmer was heard to cry: "this unworthy right hand!"

It was claimed that just before he died Cranmer managed to throw the speech he intended to make in St Mary's Church into the crowd. A man whose initials were J.A. picked it up and made a copy of it. Although he was a Catholic, he was impressed by Cranmer's courage, and decided to keep it and it was later passed on to John Foxe, who published in his Book of Martyrs.

Jasper Ridley has argued that as a propaganda exercise, Cranmer's death was a disaster for Queen Mary. "An event which has been witnessed by hundreds of people cannot be kept secret and the news quickly spread that Cranmer was repudiated his recantations before he died. The government then changed their line; they admitted that Cranmer had retracted his recantations were insincere, that he had recanted only to save his life, and that they had been justified in burning him despite his recantations. The Protestants then circulated the story of Cranmer's statement at the stake in an improved form; they spread the rumour that Cranmer had denied at the stake that he had ever signed any recantations, and that the alleged recantations had all been forged by King Philip's Spanish friars."

In a three year period over 300 men and women were burnt for heresy. The executions usually took place on market day so they would be seen by the largest number of people possible. Supporters of the condemned heretic would also attend the execution. In some cases people demonstrated against the idea of killing heretics. If caught, these people would be taken away and flogged. Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued: "The punishment of death by burning was an appallingly cruel one, but it was not this that shocked contemporaries - after all, in an age that knew nothing of anaesthetics, a great deal of pain had to be endured by everybody at one time or another, and the taste for public executions, bear-baiting and cock-fighting suggests a callousness that blunted susceptibilities." (100) During this period around 280 people were burnt at the stake. This compare to only 81 heretics executed during the reign of Henry VIII (1509-1547).

In the summer of 1558 Mary began to get pains in her stomach and thought she was pregnant. This was important to Mary as she wanted to ensure that a Catholic monarchy would continue after her death. It was not to be. Mary had stomach cancer. Mary now had to consider the possibility of naming Elizabeth as her successor. "Mary postponed the inevitable naming of her half-sister until the last minute. Although their relations were not always overtly hostile, Mary had long disliked and distrusted Elizabeth. She had resented her at first as the child of her own mother's supplanter, more recently as her increasingly likely successor. She took exception both to Elizabeth's religion and to her personal popularity, and the fact that first Wyatt's and then Dudley's risings aimed to install the princess in her place did not make Mary love her any more. But although she was several times pressed to send Elizabeth to the block, Mary held back, perhaps dissuaded by considerations of her half-sister's popularity, compounded by her own childlessness, perhaps by instincts of mercy." On 6th November she acknowledged Elizabeth as her heir.

Mary died, aged forty-two, on 17th November 1558.

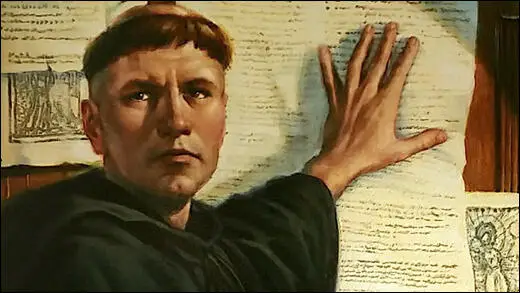

On this day in 1546 Martin Luther died. In 1508 Luther began studying at the newly founded University of Wittenberg. He was awarded his Doctor of Theology on 21st October 1512 and was appointed to the post of professor in biblical studies. He also began to publish theological writings. Luther was considered to be a good teacher. One of his students commented that he was "a man of middle stature, with a voice that combined sharpness in the enunciation of syllables and words, and softness in tone. He spoke neither too quickly nor too slowly, but at an even pace, without hesitation and very clearly."

Luther began to question traditional Catholic teaching. This included the theology of humility (whereby confession of one's own utter sinfulness is all that God asks) and the theology of justification by faith (in which human beings are seen as incapable of any turning towards God by their own efforts).

In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar arrived in Wittenberg. He was selling documents called indulgences that pardoned people for the sins they had committed. Tetzel told people that the money raised by the sale of these indulgences would be used to repair St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Luther was very angry that Pope Leo X was raising money in this way. He believed that it was wrong for people to be able to buy forgiveness for sins they had committed. Luther wrote a letter to the Bishop of Mainz, Albert of Brandenburg, protesting the sale of indulgences.

On 31st October, 1517, Martin Luther affixed to the castle church door, which served as the "black-board" of the university, on which all notices of disputations and high academic functions were displayed, his Ninety-five Theses. The same day he sent a copy of the Theses to the professors of the University of Mainz. They immediately agreed that they were "heretical". For example, Thesis 86, asks: "Why does not the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with his own money rather than with the money of poor believers?"

As Hans J. Hillerbrand has pointed out: "By the end of 1518, according to most scholars, Luther had reached a new understanding of the pivotal Christian notion of salvation, or reconciliation with God. Over the centuries the church had conceived the means of salvation in a variety of ways, but common to all of them was the idea that salvation is jointly effected by humans and by God - by humans through marshalling their will to do good works and thereby to please God, and by God through his offer of forgiving grace. Luther broke dramatically with this tradition by asserting that humans can contribute nothing to their salvation: salvation is, fully and completely, a work of divine grace."

Pope Leo X ordered Luther to stop stirring up trouble. This attempt to keep Luther quiet had the opposite effect. Luther now started issuing statements about other issues. For example, at that time people believed that the Pope was infallible (incapable of error). However, Luther was convinced that Leo X was wrong to sell indulgences. Therefore, Luther argued, the Pope could not possibly be infallible.

During the next year Martin Luther wrote a number of tracts criticising the Papal indulgences, the doctrine of Purgatory, and the corruptions of the Church. "He had launched a national movement in Germany, supported by princes and peasants alike, against the Pope, the Church of Rome, and its economic exploitation of the German people."

Johann Tetzel published a response to Luther's tracts. Tetzel's Theses opposed all of Luther's suggested reforms. Henry Ganss has admitted that it was probably a mistake to give Tetzel this task. "It must be admitted that they at times gave an uncompromising, even dogmatic, sanction to mere theological opinions, that were hardly consonant with the most accurate scholarship. At Wittenberg the created wild excitement, and an unfortunate hawker who offered them for sale, was mobbed by the students, and his stock of about eight hundred copies publicly burned in the market square - a proceeding that met with Luther's disapproval."

In 1520 Martin Luther published To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation. In the tract he argued that the clergy were unable or unwilling to reform the Church. He suggested the kings and princes must step in and carry out this task. Luther went on to claim that reform is impossible unless the Pope's power in Germany is destroyed. He urged them to bring an end to the rule of clerical celibacy and the selling of indulgences. "The German nation and empire must be freed to live their own lives. The princes must make laws for the moral reform of the people, restraining extravagance in dress or feasts or spices, destroying the public brothels, controlling the bankers and credit."

Humanists like Desiderius Erasmus had criticised the Catholic Church but Luther's attack was very different. As Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "From the beginning there was a fundamental difference between Erasmus and Luther, between the humanists and the Lutherans. The humanists wished to remove the corruptions and to reform the Church in order to strengthen it; the Lutherans, almost from the beginning, wished to overthrow the Church, believing that it had become incurably wicked and was not the Church of Christ on earth."

On 15th June 1520, Pope Leo X issued Exsurge Domine, condemning the ideas of Martin Luther as heretical and ordering the faithful to burn his books. Luther responded by burning books of canon law and papal decrees. On 3rd January 1521 Luther was excommunicated. However, most German citizens supported Luther against the Pope. The German papal legate wrote: "All Germany is in revolution. Nine tenths shout Luther as their war-cry; and the other tenth cares nothing about Luther, and cries: Death to the court of Rome!"

Martin Luther was protected by Frederick III of Saxony. Pressure was placed on Emperor Charles V by the Pope to deal with Luther. Charles responded by claiming: "I am born of the most Christian emperors of the noble German nation, of the Catholic kings of Spain, the archdukes of Austria, the dukes of Burgundy, who were all to the death true sons of the Roman church, defenders of the Catholic faith, of the sacred customs, decrees and usages of its worship... Therefore I am determined to set my kingdoms and dominions, my friends, my body, my blood, my life, my soul upon the unity of the Church and the purity of the faith."

Charles V was totally opposed to the ideas of Martin Luther and it is reported that when he was presented with a copy of To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation he tore it up in a rage. However, he was in a difficult position. As Derek Wilson has pointed out: "In most of his rag-bag of territories Charles ruled by right of inheritance but in Germany he held the crown by consent of the electors, chief among whom was Frederick of Saxony."

The twenty-year old Emperor Charles invited Martin Luther to meet him in the city of Worms. On 18th April 1521, Charles asked Luther if he was willing to recant. He replied: "Unless I am proved wrong by Scriptures or by evident reason, then I am a prisoner in conscience to the Word of God. I cannot retract and I will not retract. To go against the conscience is neither safe nor right. God help me."

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey suggested to Henry VIII that he might want to distinguish himself from other European princes by showing himself to be erudite as well as a supporter of the Roman Catholic Church. With the help of Wolsey and Thomas More, Henry composed a reply to Martin Luther entitled In Defence of the Seven Sacraments. Pope Leo X was delighted with the document and in 1521 he granted him the title, Defender of the Faith. Luther responded by denouncing Henry as the "king of lies" and a "damnable and rotten worm". As Peter Ackroyd has pointed out: "Henry was never warmly disposed towards Lutherism and, in most respects, remained an orthodox Catholic."

Martin Luther had such a strong following in Germany the Emperor was reluctant to call for his arrest. Instead he was declared an outlaw. Luther returned to the protection of Frederick III of Saxony who had no intention of surrendering him to the Catholic authorities to be burnt or hanged. Luther went to live in Wartburg Castle where he began to translate the New Testament into German.

There had been German versions of the Bible for nearly 50 years but they were of poor quality and were considered unreadable. Luther faced the basic problem of every translator: that of converting the original into the idioms and thought patterns of his own day. Luther's first version of the New Testament was published in September, 1522. It was immediately banned and people faced the possibility of arrest, imprisonment and death by owning, reading and selling copies of Luther's Bible.

Hans Holbein was commissioned to create an image of Martin Luther. Published in 1523 it depicted Luther as the Greek super-hero and god, Hercules, attacking people with a viciously spiked club. In the picture, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, William of Ockham, Duns Scotus and Nicholas of Lyra already lay bludgeoned to death at his feet and the German inquisitor, Jacob van Hoogstraaten was about to receive his fatal stroke. Suspended from a ring in Luther's nose was the figure of Pope Leo X.

The author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "What was clever about this print (and what has made it difficult for later ages to determine its true message) was that it was capable of various interpretations. Followers of Luther could see their champion represented as a truly god-like being of awesome power, the agent of divine vengeance. Classical scholars, delighting in the many subtle allusions (such as the representation of the triple-tiaraed pope as the three-bodied monster, Geryon) could applaud the vivid representation of Luther as the champion of falsehood over medieval error. Yet, papalists could look on the same image and see in it a vindication of Leo's description of the uncouth German as the destructive wild boar in the vineyard and, for this reason, the engraving received a very mixed reception in Wittenberg."

Martin Luther's ideas had a major impact on young men studying to be priests. Students at Cambridge University would meet at the White Horse tavern. It was nicknamed "Little Germany" as the Lutheran creed was discussed within its walls, and the participants were known as "Germans". Those involved in the debates about religious reform included Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, Nicholas Ridley, Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Shaxton and Matthew Parker. These students also went to hear the sermons of preachers such as Robert Barnes and Thomas Bilney.

If the Pope could be wrong about indulgences, Luther argued he could be wrong about other things. For hundreds of years popes had only allowed bibles to be printed in Latin or Greek. Luther pointed out that only a minority of people in Germany could read these languages. Therefore to find out what was in the Bible they had to rely on priests who could read and speak Latin or Greek. Luther, on the other hand, wanted people to read the Bible for themselves.

Martin Luther also began work on what proved to be one of his foremost achievements - the translation of the New Testament into the German vernacular. "This task was an obvious ramification of his insistence that the Bible alone is the source of Christian truth and his related belief that everyone is capable of understanding the biblical message. Luther’s translation profoundly affected the development of the written German language. The precedent he set was followed by other scholars, whose work made the Bible widely available in the vernacular and contributed significantly to the emergence of national languages."

Influenced by Luther's writings, William Tyndale began work on an English translation of the New Testament. This was a very dangerous activity for ever since 1408 to translate anything from the Bible into English was a capital offence. In 1523 he travelled to London for a meeting with Cuthbert Tunstall, the Bishop of London. Tunstall refused to support Tyndale in this venture but did not organize his persecution. Tyndale later wrote that he now realized that "to translate the New Testament… there was no place in all England" and left for Germany in April 1524.

Tyndale argued: "All the prophets wrote in the mother tongue... Why then might they (the scriptures) not be written in the mother tongue... They say, the scripture is so hard, that thou could never understand it... They will say it cannot be translated into our tongue... they are false liars." In Cologne he translated the New Testament into English and it was printed by Protestant supporters in Worms.

Tyndale's Bible was heavily influenced by the writings of Martin Luther. This is reflected in the way he altered the meaning of certain important concepts. "Congregation" was employed instead of "church", and "senior" instead of "priest", "penance", "charity", "grace" and "confession" were also silently removed. Melvyn Bragg has pointed out. Tyndale "loaded our speech with more everyday phrases than any other writer before or since". This included “under the sun”, “signs of the times”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “lick the dust”, “fall flat on his face”, “the land of the living”, “pour out one’s heart”, “the apple of his eye”, “fleshpots”, “go the extra mile” and “the parting of the ways”. Bragg adds: "Tyndale deliberately set out to write a Bible which would be accessible to everyone. To make this completely clear, he used monosyllables, frequently, and in such a dynamic way that they became the drumbeat of English prose."

Henry Ganss has argued: "Luther the reformer had become Luther the revolutionary; the religious agitation had become a political rebellion... Luther had one prominent trait of character, which in the consensus of those who have made him a special study, overshadowed all others. It was an overweening confidence and unbending will, buttressed by an inflexible dogmatism. He recognized no superior, tolerated no rival, brooked no contradiction." (35)

Martin Luther had been born a peasant and he was sympathetic to their plight in Germany and attacked the oppression of the landlords. In December 1521 he warned that the peasants were close to rebellion: "Now it seems probable that there is danger of an insurrection, and that priests, monks, bishops, and the entire spiritual estate may be murdered or driven into exile, unless they seriously and thoroughly reform themselves. For the common man... is neither able nor willing to endure it longer, and would indeed have good reason to lay about him with flails and cudgels, as the peasants are threatening to do."

Thomas Müntzer was a follower of Luther and argued that his reformist ideas should be applied to the economics and politics as well as religion. Müntzer began promoting a new egalitarian society. Frederick Engels wrote that Müntzer believed in "a society with no class differences, no private property and no state authority independent of, and foreign to, members of society".

In August 1524, Müntzer became one of the leaders of the uprising later known as the Peasants’ War. In one speech he told the peasants: "The worst of all the ills on Earth is that no-one wants to concern themselves with the poor. The rich do as they wish... Our lords and princes encourage theft and robbery. The fish in the water, the birds in the sky, and the vegetation on the land all have to be theirs... They... preach to the poor: 'God has commanded that thou shalt not steal'. Thus, when the poor man takes even the slightest thing he has to hang."

Martin Luther seemed to take the side of the peasants and in May 1525 he published An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia: "To the Princes and Lords... We have no one on earth to thank for this mischievous rebellion, except you princes and lords; and especially you blind bishops and mad priests and monks... since you are the cause of this wrath of God, it will undoubtedly come upon you, if you do not mend your ways in time. ... The peasants are mustering, and this must result in the ruin, destruction, and desolation of Germany by cruel murder and bloodshed, unless God shall be moved by our repentance to prevent it... If these peasants do not do it for you, others will... It is not the peasants, dear lords, who are resisting you; it is God Himself. ... To make your sin still greater, and ensure your merciless destruction, some of you are beginning to blame this affair on the Gospel and say it is the fruit of my teaching... You did not want to know what I taught, and what the Gospel is; now there is one at the door who will soon teach you, unless you amend your ways."

The following year Müntzer succeeded in taking over the Mühlhausen town council and setting up a type of communistic society. By the spring of 1525 the rebellion had spread to much of central Germany. The peasants published their grievances in a manifesto titled The Twelve Articles of the Peasants; the document is notable for its declaration that the rightness of the peasants’ demands should be judged by the Word of God, a notion derived directly from Luther’s teaching that the Bible is the sole guide in matters of morality and belief.

Some of Luther's critics blamed him for the Peasants' War: "The peasant outbreaks, which in milder forms were previously easily controlled, now assumed a magnitude and acuteness that threatened the national life of Germany.... A fire of repressed rebellion and infectious unrest burned throughout the nation. This smouldering fire Luther fanned to a fierce flame by his turbulent and incendiary writings, which were read with avidity by all, and by none more voraciously than the peasant, who looked upon 'the son of a peasant' not only as an emancipator from Roman impositions, but the precursor of social advancement."

Although it is true that Martin Luther he agreed with many of the peasants' demands, he hated armed strife. He travelled round the country districts, risking his life to preach against violence. Martin Luther also published the tract, Against the Murdering Thieving Hordes of Peasants, where he urged the princes to "brandish their swords, to free, save, help, and pity the poor people forced to join the peasants - but the wicked, stab, smite, and slay all you can." Some of the peasant leaders reacted to the tract by describing Luther as a spokesman for the oppressors.

In the tract Luther made it clear that he now had no sympathy for the rebellious peasants: "The pretences which they made in their twelve articles, under the name of the Gospel, were nothing but lies. It is the devil's work that they are at.... They have abundantly merited death in body and soul. In the first place they have sworn to be true and faithful, submissive and obedient, to their rulers, as Christ commands... Because they are breaking this obedience, and are setting themselves against the higher powers, willfully and with violence, they have forfeited body and soul, as faithless, perjured, lying, disobedient knaves and scoundrels are wont to do."

Luther called on the nobility of Germany to destroy the rebels: "They (the peasants) are starting a rebellion, and violently robbing and plundering monasteries and castles which are not theirs, by which they have a second time deserved death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers ... if a man is an open rebel every man is his judge and executioner, just as when a fire starts, the first to put it out is the best man. For rebellion is not simple murder, but is like a great fire, which attacks and lays waste a whole land. Thus rebellion brings with it a land full of murder and bloodshed, makes widows and orphans, and turns everything upside down, like the greatest disaster."

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007), pointed out the Luther strongly defended the inequality that existed in 16th century Germany. "Luther told the peasants... the rebels have no mandate from God to challenge their masters and, as Jesus had shown by his rebuking of Peter who had drawn the sword in the Garden of Gethsemane, violence was never an option for the Christian. Vengeance and the rightings of wrongs belonged to God... Luther went through their twelve demands. The abolition of serfdom was fanciful nonsense; equality under the Gospel does not translate into the removal of social grading. Without class distinctions society would disintegrate into anarchy. By the same token, the withholding of tithes would be an unwarranted attack on the economic working of the prevailing system."

Thomas Müntzer led about 8,000 peasants into battle in Frankenhausen on 15th May 1525. Müntzer told the peasants: "Forward, forward, while the iron is hot. Let your swords be ever warm with blood!" Armed with mostly scythes and flails they stood little chance against the well-armed soldiers of Philip I of Hesse and Duke George of Saxony. The combined infantry, cavalry and artillery attack resulted in the peasants fleeing in panic. Over 3,000 peasants were killed whereas only four of the soldiers lost their lives.

Müntzer was captured, tortured and finally executed on 27th May, 1525. His head and body were displayed as a warning to all those who might again preach treasonous doctrines. Other ringleaders were also executed. "Meanwhile, all over Germany, the mopping-up operation got under way as the princes exacted their revenge and reasserted their authority. Men who had taken up arms or simply against their masters or who fell foul of informers were imprisoned or beheaded... To any unbiased commentator, then or twice, the reaction has seemed to be out of all proportion to the offence."

Martin Luther wrote to his friend, Nicolaus von Amsdorf, justifying his position on the Peasants War: "My opinion is that it is better that all the peasants be killed than that the princes and magistrates perish, because the rustics took the sword without divine authority. The only possible consequence of their satanic wickedness would be the diabolic devastation of the kingdom of God. Even if the princes abuse their power, yet they have it of God, and under their rule the kingdom of God at least has a chance to exist. Wherefore no pity, no tolerance should be shown to the peasants, but the fury and wrath of God should be visited upon those men who did not heed warning nor yield when just terms were offered them, but continued with satanic fury to confound everything... To justify, pity, or favor them is to deny, blaspheme, and try to pull God from heaven."

In July 1525, published An Open Letter Against the Peasants, where he attempted to regain the support of those who had supported the rebels: "All my words were against the obdurate, hardened, blinded peasants, who would neither see nor hear, as anyone may see who reads them; and yet you say that I advocate the slaughter of the poor captured peasants without mercy.... On the obstinate, hardened, blinded peasants, let no one have mercy. They say... that the lords are misusing their sword and slaying too cruelly. I answer: What has that to do with my book? Why lay others' guilt on me? If they are misusing their power, they have not learned it from me; and they will have their reward ... See, then, whether I was not right when I said, in my little book, that we ought to slay the rebels without any mercy. I did not teach, however, that mercy ought not to be shown to the captives and those who have surrendered."

Martin Luther wrote to Philipp Melanchthon asking his for his support in this struggle: "I hear of nothing said or done by them that Satan could not also do or imitate... God has never sent anyone, not even the Son himself, unless he was called through men or attested by signs... I have always expected Satan to touch this sore, but he did not want to do it through the papists. It is among us and among our followers that he is stirring up this grievous schism, but Christ will quickly trample hum under our feet."

Luther also tackled the subject of priests and marriage. He argued out that nowhere in the Bible was the celibacy of priests commanded nor their marriage forbidden. He pointed out that all the apostles except John were married, and that the Bible portrays Paul as a widower. Luther went on to suggest that the prohibition of marriage increased sin, shame, and scandal without end. He quoted from Paul’s First Epistle to Timothy to justify his position: “A bishop then must be blameless, the husband of one wife, vigilant, sober, of good behaviour, given to hospitality, apt to teach; not given to wine, no striker, not greedy of filthy lucre; but patient, not a brawler, not covetous.” Luther denied that this or any other pope had any standing whatever to legislate human sexuality. “Does the pope set up laws?” he had asked in one essay. “Let him set them up for himself and keep hands off my liberty.”

Katherine von Bora was one of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, when he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels. She was a woman from a noble family who had been placed in the convent as a child. For the next two years she worked as a servant in the house of the artist, Lucas Cranach. According to Derek Wilson: "Catherine was comely (perhaps even plain); she was intelligent; and she had a mind of her own. She set her face against being married off to the first man who would have her.... At length a suitor was found who did please her. This was Jerome Baumgartner, a wealthy, young burger from Nuremberg. Sadly, Baumgartner's family persuaded him that he could do better for himself and a disconsolate Catherine was left on the shelf."

Martin Luther then tried to arrange for Katherine to marry Casper Glatz, a fellow theologian. She appealed to Nicolaus von Amsdorf and he wrote to his friend on her behalf: "What in the devil are you up to that you try to persuade good Kate and force that old skinflint, Glatz, on her. She doesn't go for him and has neither love nor affection for him." Catherine made it clear that she wanted to marry Luther.

On a visit to his parents, Luther's father asked him: how long was Martin going to go on advising other ex-monks to marry while refusing to set an example himself. On 13th June 13, 1525, Luther married Katherine. Hans J. Hillerbrand has argued that this decision was based on a number of factors. This included the fact that he regarded the Roman Catholic Church’s insistence on clerical celibacy as the work of the Devil.

Martin Luther explained his decision in a letter to Nicolaus von Amsdorf: "The rumour is true that I was suddenly married to Katherine. I did this to silence the evil mouths which are so used to complaining about me... In addition, I also did not want to reject this unique opportunity to obey my father's wish for progeny, which he so often expressed. At the same time I also wanted to confirm what I have taught by practising it; for I find so many timid in spite of such great light from the gospel. god has willed and brought about this step. For I feel neither passionate love nor burning desire for my spouse."

Even his fiercest critics admit that Luther' marriage to Katherine von Bora was a happy one. It is claimed that "Katherine proved to be a plain, frugal, domestic housewife; her interest in her fowls, piggery, fish-pond, vegetable garden, home-brewery, were deeper and more absorbing than in the most gigantic undertakings of her husband". Over the next few years she gave birth to six children: John (7th June, 1526), Elizabeth (10th December, 1527), Magdalene (4th May, 1529), Martin (9th November, 1531), Paul (28th January, 1533) and Margaret (17th December, 1534).

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has pointed out: "He (Martin Luther) began to translate the New Testament into German. He had determined that the Bible should be brought to the homes of the common people. He echoed the cry of Erasmus that the ploughman ought to be able to recite the Scripture while he was ploughing, or the weaver as he hummed to the music of his shuttle. He took a little more than a year to translate the New Testament and have it revised by his young friend and colleague Philip Melanchthon... The simplicity, the directness, the freshness, the perseverance of Luther's character appeared in the translation, as in everything else that he wrote".

The translation of the Bible into German was published in a six-part edition in 1534. Luther worked closely with Philipp Melanchthon, Johannes Bugenhagen, Caspar Creuziger and Matthäus Aurogallus on the project. There were 117 original woodcuts included in the 1534 edition issued by the Hans Lufft press in Wittenberg. This included the work of Lucas Cranach.

Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has argued: "With the New Testament Luther staked a place at the very forefront of the development of German literature. His style was vigorous, colourful and direct. Anyone reading it could almost hear the author proclaiming the sacred text and that was no fortuitous accident; Luther's written language was akin to the oral delivery of his own impassioned sermons. His translation was couched in compelling prose."

Luther commissioned such artists as Lucas Cranach the elder to make woodcuts in support of the Reformation, among them "The Birth and Origin of the Pope" (one of the series entitled The True Depiction of the Papacy, which depicts Satan excreting the Pontiff). He also commissioned Cranach to provide cartoon illustrations for his German translation of the New Testament, which became a best seller, a major event in the history of the Reformation.

At the Diet of Augsburg in 1530 Philipp Melanchthon was the leading representative of the Reformation, and it was he who prepared the Augsburg Confession, which influenced other credal statements in Protestantism. In the Confession he sought to be as inoffensive to the Catholics as possible while forcefully stating the Evangelical position. As Klemens Löffler has pointed out: "He was not qualified to play the part of a leader amid the turmoil of a troublous period. The life which he was fitted for was the quiet existence of the scholar. He was always of a retiring and timid disposition, temperate, prudent, and peace-loving, with a pious turn of mind and a deeply religious training. He never completely lost his attachment for the Catholic Church and for many of her ceremonies.... He invariably sought to preserve peace as long as might be possible."

Martin Luther wrote a pamphlet, Exhortation to all Clergy Assembled at Augsburg that caused Melanchthon considerable distress: "You are the devil's church! She (the Catholic Church) is a liar against God's word and a murderess, for she sees that her god, the devil, is also a liar and a murderer... We want you to be forced to it by God's word and have you worn down like blasphemers, persecutors and murderers, so that you humble yourself before God, confess your sins, murder and blasphemy against God's word."

Luther had the pamphlet printed and 500 copies sent to Augsburg. As Derek Wilson, the author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) pointed out: "While Melanchthon and the others were making serious efforts to reach a compromise solution, their mentor, like some prophet of old, was despatching from his mountain retreat messages of fiery denunciation and exhortations to his friends to stick to their guns."

Melanchthon's Apology of the Confession of Augsburg (1531) became an important document in the history of Lutherism. Melanchthon was accused of being too willing to compromise with the Catholic Church. However, he argued: "I know that the people decry our moderation; but it does not become us to heed the clamour of the multitude. We must labour for peace and for the future It will prove a great blessing for us all if unity be restored in Germany."

Owen Chadwick, the author of The Reformation (1964) has written in some detail about the relationship between Luther and Melanchthon: "Melanchthon, seeing Luther's faults and regretting them, admired him with a rueful affection and reverenced him as the restorer of truth in the Church. His respect for tradition and authority suited Luther's underlying conservatism, and he supplied learning, a systematic theology, a mode of education, an ideal for the universities, and an even and tranquil spirit."

Anabaptism emerged in Germany during the Protestant Reformation. It is claimed that the movement had been inspired by the teachings of Martin Luther and the publication of the Bible in German. Now able to read the Bible in their own language, they began to question the teachings of the Catholic Church. One of the movement's leaders, Balthasar Hubmaier, a former pupil of Luther, pointed out: “In all disputes concerning faith and religion, the scriptures alone, proceeding from the mouth of God, ought to be our level and rule.”

The Anabaptists argued that Jesus taught that man should act in a non-violent way. They quoted him as saying: "Love your enemy and pray for those who persecute you.” (Luke 6.27) "Blessed are the peacemakers: for they shall be called sons of God." (Matthew 5.9) “Do not use force against an evil man.. But I say to you, Do not resist the one who is evil. But if anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also.” (Matthew 5.39) “Do not resist evil with evil.” (Luke 6.37) “He who lives by the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matthew 26.52)

The Anabaptists were the among the first to point out the lack of explicit biblical support for infant baptism. They repudiated their own baptism as infants. They considered the public confession of sin and faith, sealed by adult baptism, to be the only proper baptism. They agreed with Huldrych Zwingli that infants are not punishable for sin until they become aware of good and evil and can exercise their own free will, repent, and accept baptism.

Anabaptists believed that "they were the true elect of God who did not require any external authority". They therefore advocated separation of church and state. Anabaptists advocated complete freedom of belief and denied that the state had a right to punish or execute anyone for religious beliefs or teachings. This was a revolutionary notion in the 16th century and every government in Europe saw them as a potential threat to both religious and political power.

Jasper Ridley has pointed out: "The Anabaptists not only objected to infant baptism, but also denied the divinity of Christ or said that he was not born to the Virgin Mary. They advocated a primitive form of Communism, denouncing private property and urging that all goods should be owned by the people in common." Anabaptists believed all people were equal and kept their hats on before magistrates and superior officials and their pacifism made them reject military service.

Martin Luther was completely opposed to the Anabaptists and denounced people such as Balthasar Hubmaier and Pilgram Marpeck as satanic agents and enemies of the Gospel. Luther was especially upset by Hubmaier's teaching that people should not swear oaths. "Since solemn vows were a vital part of the making and sustaining of all relationships - master and apprentice, lord and servant, mercenary general and paymaster, what Hubmaier's followers proposed was nothing less than a breakdown of society." Luther argued that all Anabaptists should be "hanged as seditionists".

In his early career Martin Luther held tolerant views towards the Jews. In 1519 he had written: "Absurd theologians defend hatred for the Jews... What Jew would consent to enter our ranks when he sees the cruelty and enmity we wreak on them - that in our behavior towards them we less resemble Christians than beasts?" In 1523, he wrote: "I hope that if one deals in a kindly way with the Jews and instructs them carefully from Holy Scripture, many of them will become genuine Christians and turn again to the faith of their fathers, the prophets and patriarchs. They will only be frightened further away from it if their Judaism is so utterly rejected that nothing is allowed to remain, and they are treated only with arrogance and scorn. If the apostles, who also were Jews, had dealt with us Gentiles as we Gentiles deal with the Jews, there would never have been a Christian among the Gentiles. Since they dealt with us Gentiles in such brotherly fashion, we in our turn ought to treat the Jews in a brotherly manner in order that we might convert some of them."

Luther was confident that his writings would convert Jews to Christianity. This had not happened and in 1542 he was upset when news reached him that proselytising Jews had succeeded in converting some Christian men, who had denied Christ and submitted to circumcision. He also recorded that three rabbis had called on him, apparently with the same objective.

Soon afterwards his thirteen-year-old daughter, Magdalene, died. He confided to a friend: "My most beloved daughter Magdalene has departed from me and gone to the heavenly Father. She passed away having total faith in Christ. I have overcome the emotional shock typical of a father but only with a certain threatening murmur against death. By means of this disdain I have tamed my tears. I loved her so very much."

In the weeks following his daughter's death he wrote On the Jews and Their Lies. The greater part of the work was a careful analysis of the Old Testament. However, in the final section of the book, Luther addressed himself to the question of how Christian rulers should treat their Jewish subjects. As Derek Wilson pointed out: "Attitudes to his harsh and uncompromising advice have inevitably been coloured by the appalling events of later centuries and predominately by the Holocaust... In 1523 he had been an assimilationist; now he had become an exclusionist. No longer were the Jews to be won over by kindness."

Luther wrote: "What shall we Christians do with this rejected and condemned people, the Jews? Since they live among us, we dare not tolerate their conduct, now that we are aware of their lying and reviling and blaspheming. If we do, we become sharers in their lies, cursing and blasphemy... First to set fire to their synagogues or schools and to bury and cover with dirt whatever will not burn, so that no man will ever again see a stone or cinder of them... Second, I advise that their houses also be razed and destroyed. For they pursue in them the same aims as in their synagogues. Instead they might be lodged under a roof or in a barn, like the gypsies. This will bring home to them that they are not masters in our country, as they boast, but that they are living in exile and in captivity, as they incessantly wail and lament about us before God. Third, I advise that all their prayer books and Talmudic writings, in which such idolatry, lies, cursing and blasphemy are taught, be taken from them... Fourth, I advise that their rabbis be forbidden to teach henceforth on pain of loss of life and limb."

The author of Out of the Storm: The Life and Legacy of Martin Luther (2007) has attempted to defend Luther's tract: "Luther did not advocate extermination. And he was not a racist. His objection was entirely to the Jews' religious beliefs and the behaviour that stemmed from those beliefs. He did not support inquisitorial methods to obtain conversions - use of informers, third-degree interrogation, torture and the threat of the stake... To individual Jews (of whom he met very few) he was his usual open, generous self."

Hans J. Hillerbrand takes a less sympathetic approach to Martin Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies: "Such were hardly irenic words from a minister of the gospel, and none of the explanations that have been offered - his deteriorating health and chronic pain, his expectation of the imminent end of the world, his deep disappointment over the failure of true religious reform - seem satisfactory." Roland H. Bainton agrees and has written that "one could wish that Luther had died before ever this tract was written".

By this stage of his life his health was poor. "Prolonged attacks of dyspepsia, nervous headaches, chronic granular kidney disease, gout, sciatic rheumatism, middle ear abscesses, above all vertigo and gall stone colic were intermittent or chronic ailments that gradually made him the typical embodiment of a supersensitively nervous, prematurely old man. These physical impairments were further aggravated by his notorious disregard of all ordinary dietetic or hygienic restrictions."

On this day in 1609 Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon, was born in Dinton, near Salisbury. Elected to the House of Commons in 1640 he was a strong critic of Charles I and supported the impeachment of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford.

In 1641 Hyde changed sides and became a supporter of the Royalists. During the Civil War Hyde stayed with the king in Oxford.

With the defeat of the Royalist forces in 1646 Hyde went to live in Jersey. Five years later he was appointed as an adviser to Charles II in exile. On the Restoration Hyde returned to England and was given the title the Earl of Clarendon and appointed as Lord Chancellor

In 1667 Clarendon lost the support of Charles II when he criticised his private life. He went into exile where he wrote a book about the Civil War called The History of the Rebellion. Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, died in 1674.

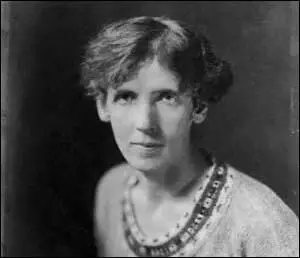

On this day in 1878 Blanche Ames was born in Lowell, Massachusetts. Her father was General Adelbert Ames, a union officer during the American Civil War, and later, Governor of Mississippi. Her mother, Blanche Butler, was the daughter of Benjamin Butler, the Governor of Massachusetts and unsuccessful presidential candidate in 1884 against Grover Cleveland.

Ames was later one of few women of her time to attend college, earning a B.A. in Art History and a diploma in Studio Art from Smith College in 1899. As class president, she delivered a commencement speech in which she observed that the graduates were "most fortunate to live in an age that - more than any other - makes it possible for women to attain the best and truest development in life" At this time she met Oakes Ames (unrelated) who taught botany at Harvard University. He began courting her with gifts of "the queerest orchids".

In 1900 Blanche married Oakes Ames. Over the next ten years they had four children. In 1910, they designed and constructed an impressive stone mansion located in North Easton, Massachusetts. The house was surrounded by 1500 acres called Borderland which the family farmed. They were Unitarians who belonged to the Unity Church of North Easton. According to Heather Miller "Their marriage was a highly successful collaboration in home and family building, art, science, technology and politics."

Blanche Ames worked closely with her husband's work and she illustrated all seven volumes of his Orchidaceae: Illustrations and Studies of the Family Orchidaceae (1901-1922). It has been claimed by Laura J. Snyder: "Blanche Ames... was soon renowned as the foremost American botanical illustrator of the age. Using the microscope and another optical device, a camera lucida, she captured the intricate form of orchids: the delicate root hairs and rhizomes, the anther cap perched over the pollen bundles, the succulent pseudobulbs. Thanks to dark shadowing and crosshatch highlights, her elegant pen-and-ink drawings boldly depict the plants against the white page. They are at once scientifically exact and artistically brilliant."

Ames was a strong supporter of women's suffrage and was a member of the the Massachusetts Suffrage Association. Her grandfather, Benjamin Butler, was one of the first American politicians to argue that women should be given the vote. Both of her parents were also advocates of women's rights, so much so that, while promising to love and honor each other in their wedding vows, they deleted the traditional pledge of the bride to obey.

In 1912 Blanche Ames joined Nina Allender and Lou Rogers in producing cartoons for the cause. "The three of them began to turn things around with their political cartoons that were witty, sharp, and attacking the power that was trying to silence them. This new and modern-day women that was being depicted as the Allender girl, showed a spirit of daring and pride as well as possessing youth. "

As Holly Bass has pointed out: "The women's suffrage movement had a serious image problem at the turn of the century, when female activists were often portrayed as obsessed feminists out to destroy American society. From 1912-15, three women artists - Annie Lucasta "Lou" Rogers, Nina Allender, and Blanche Ames - helped turn things around with political cartoons that were sharp, witty attacks on the powers that be. These works also stand as some of the first realistic representations of the 'new woman' in the popular media."

Blanche Ames political cartoons in favour of women's suffrage appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript. She also became art editor for the Woman's Journal. Established by the American Woman Suffrage Association it was edited by Lucy Stone, Mary Livermore and Julia Ward Howe and featured articles by members of the organization and cartoons were provided by Blanche Ames, Lou Rogers, John Sloan, Mary Sigsbee, Fredrikke Palmer, John Bengough, John Bengough and Rollin Kirby.

One of her most powerful cartoons was Double the Power of the Home - Two Good Votes are Better Than One that was published in October, 1915. A young "angelic-faced" woman sits with her three children in a domestic scene. She is surrounded by symbols of her hard work and virtue, suggesting that it was wrong that she was being denied the vote.

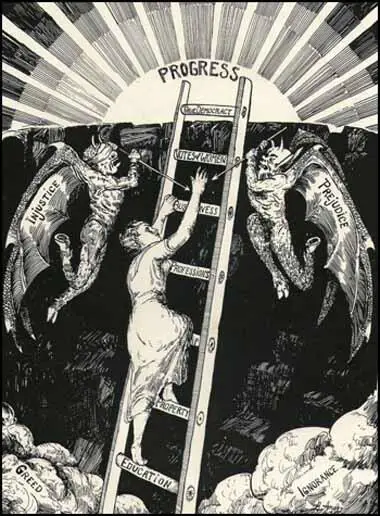

In another cartoon published in the Boston Evening Transcript (November, 1915) called The Next Rung, she attempts to capture the struggle faced by women. " The woman is being pushed down by two demons that are trying to keep her from reaching the top of the ladder, and true progress. The demons - Injustice and Prejudice - are just some of the troubles that this woman has to overcome to get the right to vote. You can see that Injustice is blind-folded, showing how Blanche felt that injustice is blind, it only sees half of the story. Blanche's cartoons were drawn to make you think... This woman has already overcome so much greed and ignorance, but now she faces more challenges. She is using her education to help her, but she is still a long way away from the top rung, and must keep climbing. She has come too far to turn back now. This was Blanche's message, this was her hope, and thanks to determined suffragists like Blanche and her contemporaries, women now have a vote, now have true democracy."

Ames was "the first public exponent of birth control in Massachusetts". She argued it was a woman's right to limit her family and in 1916 she became co-founder and president of the Massachusetts Birth Control League, that was affiliated with the national group led by Margaret Sanger. She was highly critical of the Catholic Church and in an article in the Birth Control Review she wrote: "The long arm of the Catholic Church is reaching into our legislative halls and is directing our legislators to act according to its will… We have all been troubled by the fear that this Catholic threat to our free institutions would materialize if Catholics were given positions of power in our government, but never before in so short a time have events developed in such irrefutable sequence as in this case of opposition to the Doctors' Birth Control Bill." Birth control did not become legally available in Massachusetts until 1966.

It has been pointed out that she was a strange mixture of progressive and conservative: "When the ban on dissemination of birth control information was upheld, Ames reacted by suggesting that women take the matter into their own hands. She encouraged mothers to teach birth control methods to their daughters. To help them, she created formulas for spermicidal jellies and provided instructions on how to make a diaphragm by using such everyday objects as a baby's teething ring. Ames' involvement with the Birth Control League of Massachusetts came to an end, however, when she quit in outrage at a fundraising advertisement for the league. In the advertisement, the League used the fact that 250,000 babies had been born that year to families on welfare to persuade taxpayers to support birth control."

In 1941 Ames became President of the New England Women's Hospital for Women and Children and, in a day when women physicians were a subject of controversy, she fought to have the hospital staffed "entirely by women doctors." Its purpose was to offer same sex medical care to women. In 1952 due to financial difficulties, the board of directors opened itself to the possibility of hiring male staff. "Ames vigorously fought to maintain the hospital's almost 100 year old charter. In 1952, as president of the board, Ames successfully spearheaded a massive fundraising effort which raised sufficient funds to ensure an exclusively female staff and administration for the hospital."

At the age of 80, Ames wrote the biography of her father, General Adelbert Ames, entitled Adelbert Ames: Broken Oaths and Reconstruction in Mississippi, 1853-1933 (1964). The biography was prompted by her anger at a suggestion by John F. Kennedy in his book, Profiles in Courage (1955) that her father was a carpetbagger politician in Mississippi.

Ames remained energetic throughout her life. Her daughter attempted to capture her mother in a fine epigram: "For her to have an idea was to act."

Blanche Ames, died at the age of 91 on 2nd March, 1969.

On this day in 1879 Joseph Rayner Stephens died. Stephens, the son of a Methodist minister, was born on 8th March, 1805. He was educated at the Manchester Grammar School and the Leeds Methodist School. After teaching at Cottingham for two years, Stephens became a preacher and missionary. Stephens returned to England in 1829 and soon afterwards was ordained as a Methodist minister. Stephens was appointed the minister of the Wesleyan Church in Cheltenham but in 1834 was expelled from his post for advocating the separation of church and state.

Stephens moved to Lancashire where he established an independent chapel in Ashton-under-Lyne. A large number of the people living in the town worked in the textile industry and it was not long before he became involved in the campaign for factory reform. Stephens worked closely with Richard Oastler and John Fielden. In 1836 Stephens organized a fund to support Oastler after he was dismissed from his post as the steward of Fixby Hall.

Stephens also became involved in the campaign against the 1834 Poor Law. He organised boycotts against shopowners who failed to support the reform movement and in Huddersfield in 1838 he played a prominent role in encouraging people to disrupt meetings of the local Poor Law Guardians. As a result of this campaign, Stephens was arrested from making seditious and inflammatory speeches, and in August 1839 he was found guilty and sent to prison.

On his release from prison in 1840, Stephens returned to his mission to end child labour in textile factories. In 1848 Stephens established the Ashton Chronicle, a newspaper that advocated radical social reform. Stephens worked closely with John Fielden in his campaign against child labour and after the death of his great friend in 1849, he established a group of radical reformers called the Fielden Society.

In his later years Stephens agitated on behalf of the unemployed cotton workers and supported the founding of the National Miners' Association.

On this day in 1890 Ishbel Ross was born on the Isle of Skye. Her father, James Ross, is credited with the development of the famous Drambuie drink. Ishobel attended Edinburgh Ladies College and afterwards worked as a teacher at Atholl Crescent School.

Soon after the outbreak of the First World War Ross heard Dr. Elsie Inglis give a talk on the Scottish Women's Hospital Unit. Inglis was looking for volunteers to accompany her to Serbia. Ross agreed to join Inglis and she arrived in Salonika on 22nd August 1916. She remained on the Balkan Front until July 1917.

Ishbel Ross kept a diary of her experiences and after her death in 1965, her daughter, Jess Dixon, arranged for it to enter the public domain. Little Grey Partridge was published by the Aberdeen University Press in 1988.

in Serbia. Ishbel Ross is the second from the right.

On this day in 1892 Wendell Willkie was born in Elwood, Indiana, in 1892. After graduating from Indiana University in 1913 he practised law in Ohio (1914-23) and New York City (1923-33).

In 1933 Willkie became president of the Commonwealth and Southern Corporation, a huge utilities holding company. Willkie was originally a member of the Democratic Party but was a strong opponent of some aspects of the New Deal. He was especially hostile to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), that once established, would be a major competitor to companies such as Commonwealth and Southern Corporation. When the TVA scheme went ahead Willkie joined the Republican Party.

At Philadelphia in 1940 the Republican Party chose Willkie rather than Thomas Dewey as their presidential candidate. During the campaign Willkie attacked the New Deal as being inefficient and wasteful. Although he did better than expected, Franklin D. Roosevelt beat Willkie by 27,244,160 votes to 22,305,198.

Willkie was an idealistic internationalist and was a strong opponent of American isolationism. Franklin D. Roosevelt had a great deal of respect for Willkie and in 1941 appointed him as his special representative. During the Second World War he visited England and the Far East.

Willkie played an active role in the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Along with Fiorello La Guardia, Charlie Chaplin, Vito Marcantonio, Orson Welles, Rockwell Kent and Pearl Buck, Willkie also campaigned during the summer of 1942 for the opening of a second-front in Europe.

In 1943 Willkie published his book One World where he called for a post-war world which was a union of free nations. The book, which was a best seller, laid the groundwork for the United Nations. He followed this with An American Program (1944). Wendell Willkie died of a coronary thrombosis, on 8th October, 1944.

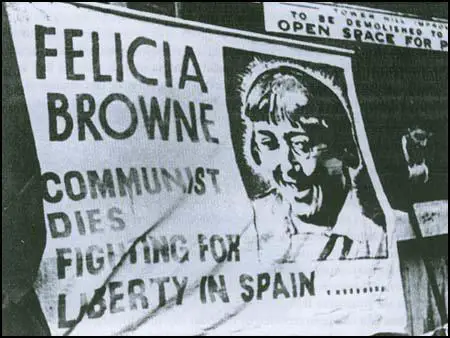

On this day in 1904 Felicia Browne was born at Thames Ditton. She studied at the St John's Wood School of Art and the Slade Art School where she studied with Henry Tonks, William Coldstream, Nan Youngman and Claude Rogers.

In 1928 Felicia Browne went to Berlin to study metalwork at Charlottenburg Technische Stadtschule, then became an apprentice to a stone mason from 1929-1931. Youngman said, "Felicia was much more aware of the political situation than any of us. In 1928 she went to Berlin to study sculpture, living with unemployed fellow artists. Witnessing the Nazis come to power led her to the Communist party, which she joined in 1933." While in Germany she took part in ant-fascist activities.