On this day on 11th June

On this day in 1509 Henry VIII of England married Catherine of Aragon. It has been argued that since the age of ten "Henry had looked up to and admired his pretty sister-in-law; and, as he had grown to manhood, and had seen how well Katherine had coped with the adversity and humiliations she had suffered, his admiration had deepened, not to passion - it would never be that - but to love in its most chivalrous form, blended with deep respect." He was just about to be eighteen (on 28th June) and she was twenty-three. The ceremony was small and private. Describing the wedding night which followed, liked to boast that he had found his wife a "maiden" (virgin). Although years later he would attempt to pass off these boasts as "jests", there seems little doubt that he had made them.

According to letters to her father, Catherine was very happy during the first few months of marriage. She enjoyed wandering in leisurely stages from "palace to palace and park to park". Catherine explained how Henry "diverts himself with jousts, birding, hunting and other innocent and honest pastimes, also in visiting different parts of his kingdom". It was claimed that they were a well-matched couple. Their intellectual tastes and educational background were similar and they both rode well and hunted with enthusiasm. Anna Whitelock argues that in many ways the "ideal royal bride" and that they "were equally learned and pious and were keen readers of theological works".

On this day in 1847 Millicent Garrett, the eighth of tenth children of Newson Garrett (1812–1893) and Louise Dunnell (1813–1903), was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk on 11th June, 1847. Millicent's father, was the grandson of Richard Garrett, who founded the successful agricultural machinery works at Leiston.

"The Garretts were a close and happy family in which children were encouraged to be physically active, read widely, speak their minds, and share in the political interests of their father, a convert from Conservatism to Gladstonian Liberalism, a combative man, and a keen patriot".

Millicent's father had originally ran a pawnbroker's shop in London, but by the time she was born he owned a corn and coal warehouse in Aldeburgh. The business was a great success and by the 1850s Garrett could afford to send his children away to be educated. In 1858 she was sent to a private boarding school in Blackheath.

Millicent's sister, Elizabeth Garrett, was also living in London and attempting to qualify as a doctor. and she took her to see Frederick Denison Maurice, the founder of the Christian Socialist movement. Elizabeth and her other sister, Louise, brought her into contact with people with progressive political views. Elizabeth introduced her to Emily Davies, a woman who was active in campaigning for women's rights. On one occasion, Emily told Elizabeth, "It is quite clear what has to be done. I must devote myself to securing higher education, while you open the medical profession to women. After these things are done, we must see about getting the vote." She then turned to Millicent: "You are younger than we are, Millie, so you must attend to that."

In July 1865 Louise took Millicent to hear a speech on women's rights made by the John Stuart Mill. the Radical MP for Westminster. He was one of the few members of the House of Commons who believed that women should have the vote. Millicent was deeply impressed by Mill and became one of his many loyal supporters. "This meeting kindled tenfold my enthusiasms for women's suffrage."

In 1865 a group of women in London formed a discussion group called the Kensington Society. Nine of the eleven women who attended the early meetings were unmarried and were attempting to pursue a career in education or medicine. The group eventually included Millicent Garrett, Elizabeth Garrett, Barbara Bodichon, Jessie Boucherett, Frances Power Cobbe, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Sophia Jex-Blake, Helen Taylor and Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy.

On 21st November 1865, the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The question was: "Is the extension of the Parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?" Both Barbara Bodichon and Helen Taylor submitted a paper on the topic. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote.

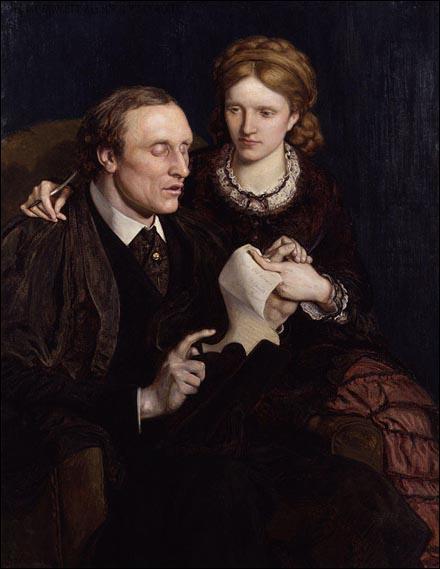

When she was eighteen, at a party given by the radical MP, Peter Alfred Taylor, Millicent Garrett met Henry Fawcett, the MP for Brighton. Fawcett, who had been blinded in a shooting accident in 1857, had been expected to marry Millicent's older sister Elizabeth, but in 1865 she decided to concentrate her efforts on becoming a doctor. Henry and Millicent became close friends and even though she was warned against marrying a disabled man, fourteen years her senior, the couple was married on 23rd April 1867. According to Henry, the marriage was based, in Fawcett's words, on "perfect intellectual sympathy"

On this day in 1854 Olivia Washington, the daughter of a slave, was born in Mercer County, Virginia. The family moved to Ironton, Ohio, where Olivia attended the local high school. Eventually she moved to Memphis with her brother Joseph and her sister Margaret.

Olivia became a teacher in Memphis but was soon on her own after the death of her sister and the killing of her brother by the Ku Klux Klan. In 1878 Olivia moved back to Ohio where she enrolled at the Hampton Institute where she met a fellow student, Booker T. Washington. In 1881 Olivia helped Washington establish the Tuskegee Institute.

In 1884 Washington's first wife, Fannie Smith, died, and two years later he married Olivia. Olivia was a strong supporter of women's rights and in 1886 gave a talk to the Alabama State Teachers' Association on How Shall We Make the Women of Our Race Stronger?

Olivia Davidson Washington had two children, but her health was never very good and she died of tuberculosis of the larynx on 9th May, 1889.

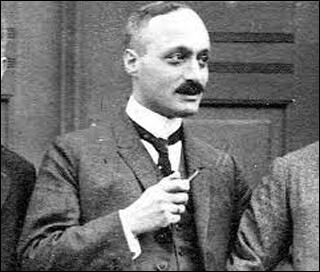

On this day in 1934, Hjalmar Schacht had a private meeting with the Governor of the Bank of England, his personal friend and business associate, Montagu Norman. Both men were members of the Anglo-German Fellowship group and shared a "fundamental dislike" of the "French, Roman Catholics, Jews". Schacht told Norman that there would be no "second revolution" and that the SA were about to be purged.

Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, Hermann Göring and Theodore Eicke worked on drawing up a list of people who were to be eliminated. It was known as the "Reich List of Unwanted Persons". The list included Ernst Röhm, Edmund Heines, Karl Ernst, Hans Erwin von Spreti and Julius Uhl of the SA, Gregor Strasser, Kurt von Schleicher, Hitler's predecessor as chancellor, Gustav von Kahr, who crushed the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Herbert von Bose and Edgar Jung, two men who worked for Franz von Papen and Fritz Gerlich, a journalist who had investigated the death of Hitler's niece, Geli Raubal.

Also on the list was Erich Klausener, the President of the Catholic Action movement, who had been making speeches against Hitler. It was feared that he was building up a strong following from within the Catholic Church. On 24th June, 1934, Klausener had organized a meeting held at Hoppegarten racecourse, where he spoke out against political oppression in front of an audience of 60,000.

On the evening of 28th June, 1934, Hitler telephoned Röhm to convene a conference of the Sturmabteilung (SA) leadership at Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse, two days later. "The call served the double purpose of gathering the SA chiefs in one out-of-the-way spot, and reassuring Röhm that, despite the rumours flying about, their mutual compact was safe. No doubt Röhm expected the discussion to centre on the radical change of government in his favour promised for the autumn."

The following day Hitler held a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. He told him that he had decided to act against Röhm and the SA. Hitler felt he could not take the risk of "breaking with the conservative middle-class elements in the Reichswehr, industry, and the civil service". By eliminating Röhm he could make it clear that he rejected the idea of a "socialist revolution". Although he disagreed with the decision, Goebbels decided not to speak out against "Operation Humingbird" in case he was also eliminated.

On 29th June, Karl Ernst got married and as he planned to go on his honeymoon and therefore could not attend the SA meeting at the Hanselbauer Hotel. Ernst Röhm and Hermann Göring both attended the wedding. (28) Later that day he alerted the Berlin SA that he had heard rumours that there was a danger of a putsch against Hitler by the right-wing of the party.

At around 6.30 in the morning of 30th June, Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic."

Edmund Heines was found in bed with his chauffeur and along with Röhm were taken to Stadelheim Prison. At the Munich railroad station, the SA leaders were beginning to arrive. As they alighted from the incoming trains they were taken into custody by SS troops. It is estimated that about 200 senior SA officers were arrested during what became known as the Night of the Long Knives.

One of Röhm's boyfriends, Karl Ernst, and the head of the SA in Berlin, had just married and was driving to Bremen with his bride to board a ship for a honeymoon in Madeira. His car was overtaken by Schutzstaffel (SS) gunman, who fired on the car, wounding his wife and his chauffeur. Ernst was taken back to SS headquarters and executed later that day.

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Röhm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Göring and Himmler, Hitler agreed that Röhm should die. Himmler ordered Theodor Eicke to carry out the task. Eicke and his adjutant, Michael Lippert, travelled to Stadelheim Prison in Munich where Röhm was being held. Eicke placed a pistol on a table in Röhm's cell and told him that he had 10 minutes in which to use the weapon to kill himself. Röhm replied: "If Adolf wants to kill me, let him do the dirty work."

According to Paul R. Maracin, the author of The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004): "Ten minutes later, SS officers Michael Lippert and Theodor Eicke appeared, and as the embittered, scar-faced veteran of verdun defiantly stood in the middle of the cell stripped to the waist, the two SS officers riddled his body with revolver bullets." Eicke later claimed that Röhm fell to the floor moaning "Mein Führer".

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary: "Executions nearly finished. A few more are necessary. That is difficult, but necessary... It is difficult, but is not however to be avoided. There must be peace for ten years. The whole afternoon with the Führer. I can't leave him alone. He suffers greatly, but is hard. The death sentences are received with the greatest seriousness. All in all about 60."

Time Magazine reported that the men had been executed as a result of a conflict between the SS and SA. It claimed that Hermann Göring and Gustav Krupp had been involved in the conspiracy. It reported that "Röhm was shot in the back next day by a firing squad". The magazine also reported that the Nazi government insisted that Herbert von Bose had committed suicide "until it could no longer be concealed that his death was due to six bullets".

Goebbels broadcast the Nazi account of the executions on 10th July. He thanked the German press for "standing by the government with commendable self-discipline and fair-mindedness" and accused the foreign press of issuing false reports so as to create confusion. He stated that these newspapers and magazines had been involved in a "campaign of lies" which he compared to the "atrocity-story campaign waged against Germany" during the First World War.

Hitler made a speech where he explained the Night of the Long Knives. He stated that he acted as "the Supreme Justiciar of the German Volk" and had used this violence "to prevent a revolution". A retrospective law was passed to legitimize the murders. The German judiciary made no protest about the use of the law to legalize murder. These events, however, had a major impact on the outside world: "The killings of 30 June and succeeding days were also an important moment in the history of the Nazi movement. Before the people of Germany, and the outside world, the leaders of the Party were revealed as calculating killers."

On this day in 1940 the death of fighter pilot Edgar James Kain is reported in The Manchester Guardian. "Flying Officer E.J. (Cobber) Kain, the distinguished New Zealand war pilot has been killed in a flying accident... Kain, who was twenty-two, was the first British airman to win distinction in France in the present war. He was awarded the D.F.C in March for his gallantry in attacking with another aircraft seven enemy bombers and chasing them into German territory. Previously 'Cobber' had shot down five enemy machines, two Dornier bombers and three Messerschmitt fighters. When on leave in April he announced his engagement to Miss Joyce Phillips, a 23-year-old actress, who was then appearing at the Repertory Theatre Peterbrough. They had hoped to be married in July, and his mother and sister had planned to be present at the wedding."

On the outbreak of the Second World War Kain was a member of 73 Squadron. On 8th November 1939 Kain shot down a Dornier D017 reconnaissance aircraft. A few days later he brought down a second Dornier.

As a result of bad weather Kain saw little action for the next three months. However, on 1st March, 1940, Kain shot down a Messerschmitt Bf 109 before being hit by his companion and he was forced to crash land in Metz. He shot down another BF 109 on 26th March but once again his plane was badly damaged and he was had to bale out and suffered burns to his face.

During the summer of 1940 Kain became the best known flying ace in Britain when he shot down another ten German aircraft over France. On the 7th June 190, Edgar James Kain was ordered to return to England. A group of friends decided to see him off and while performing a series of low level aerobatics in his Spitfire he crashed on the airfield and was killed.

On this day in 1945 scientist James Franck, a member of Manhattan Project, argued against dropping the atom bomb in a letter to President Harry S. Truman. "The military advantages and the saving of American lives achieved by the sudden use of atomic bombs against Japan may be outweighed by the ensuing loss of confidence and by a wave of horror and repulsion sweeping over the rest of the world and perhaps even dividing public opinion at home. From this point of view, a demonstration of the new weapon might best be made, before the yes of representatives of all the United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America could say to the world, "You see what sort of a weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future if other nations join us-in this renunciation and agree to the establishment of an efficient international control."

On this day in 1963 John F. Kennedy makes important speech on civil rights.

The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much.

We preach freedom around the world, and we mean it. And we cherish our freedom here at home. But are we to say to the world - and much more importantly to each other - that this is the land of the free, except for the Negroes; that we have no second-class citizens, except Negroes; that we no class or caste system, no ghettos, no master race, except with respect to Negroes.