On this day on 9th March

On this day in 1566 David Rizzio is murdered. Rizzio was Mary Queen of Scots, most important advisor. According to his biographer, Rosalind K. Marshall "he was an ugly little man, full of his own importance, with an expensive taste in clothes... but Mary evidently felt that she could trust him. As her secretary he was constantly in her company... At the same time he did everything he could to enhance his own position, and the courtiers soon came to realize that if they wished for favours, they would have to bribe Seigneur Davie, as he was known."

Thomas Randolph, the English Ambassador to Scotland, reported to William Cecil that Rizzio was a growing influence on Mary. It was decided to spread rumours that Riccio was having an affair with the Queen of Scots. It was even suggested that Rizzio was the real father of Mary's unborn child. Lord Darnley decided to join forces with a group of protestant lords who shared a dislike of Rizzio.

On 9th March 1566, about seven o'clock in the evening, Mary was at supper with Riccio in the little room adjoining her bedchamber at Holyroodhouse. "Suddenly Darnley marched in, sat down beside Mary, and put an arm round her waist, chatting to her with unaccustomed geniality. She had scarcely replied when the startling figure of Patrick Ruthven, Lord Ruthven, appeared in the doorway, deathly pale and wearing full armour... The queen rose to her feet in alarm. Terrified, Riccio darted behind her, to cower in the window embrasure, clinging to the pleats of her gown. The royal attendants sprang forward to take Ruthven, but he pulled out a pistol and waved them back. At the same moment the earl of Morton's men rushed into the supper chamber, the table was overturned... While Andrew Ker of Fawdonside held his pistol to the queen's side, George Douglas, Darnley's uncle, snatched Darnley's dagger from his belt and stabbed Riccio. According to Mary's own description of events, this first blow was struck over her shoulder... On Darnley's orders his body, with fifty-six stab wounds, was hurled down the main staircase, dragged into the porter's lodge, and thrown across a coffer where the porter's servant stripped him of his fine clothes."

It is claimed that when Mary was told the news that David Rizzio was dead, she apparently dried her eyes and said "No more tears now. I will think upon revenge". Riccio was buried hastily in a cemetery outside Holyrood Abbey. However, later, Mary had his body exhumed and placed in the royal vault in the abbey. She then appointed his young brother Joseph Riccio to take his place as her French secretary.

On this day in 1763 William Cobbett, the son of a tavern owner, was born in Farnham, Surrey. Taught to read and write by his father, Cobbett worked as a farm labourer until 1783 when he moved to London and found work as a clerk. A year later Cobbett joined the army and eventually achieved the rank of corporal. While his regiment was in Canada, Cobbett discovered that the quartermaster was stealing from army funds. When he attempted to expose this scandal he was accused of being a troublemaker. Cobbett, who had recently married, decided to flee to France with his new bride. After seven months the couple moved to the United States where Cobbett taught English to French refugees.

In 1799 William Cobbett returned to England. Three years later he started his newspaper, the Political Register. At first he supported the Tories but he gradually became more radical. By 1806 he was a strong advocate of parliamentary reform. An unsuccessful attempt to be elected as M.P. for Honiton convinced him of the unfairness of rotten boroughs.

William Cobbett was not afraid to criticise the government in the Political Register and in 1809 he attacked the use of German troops to put down a mutiny in Ely. Cobbett was tried and convicted for sedition and sentenced to two years' imprisonment in Newgate Prison. When Cobbett was released he continued his campaign against newspaper taxes and government attempts to prevent free speech.

By 1815 the tax on newspapers had reached 4d. a copy. As few people could afford to pay 6d. or 7d. for a newspaper, the tax restricted the circulation of most of these journals to people with fairly high incomes. Cobbett was only able to sell just over a thousand copies a week. The following year Cobbett began publishing the Political Register as a pamphlet. Cobbett now sold the Political Register for only 2d. and it soon had a circulation of 40,000.

Cobbett's journal was the main newspaper read by the working class. This made Cobbett a dangerous man and in 1817 he heard that the government planned to have him arrested for sedition. Unwilling to spend another period in prison, Cobbett fled to the United States. For two years Cobbett lived on a farm in Long Island where he wrote Grammar of the English Language and with the help of William Benbow, a friend in London, continued to publish the Political Register.

William Cobbett arrived back in England soon after the Peterloo Massacre. Cobbett joined with other Radicals in his attacks on the government and three times during the next couple of years was charged with libel.

In 1821 William Cobbett started a tour of Britain on horseback. Each evening he recorded his observations on what he had seen and heard that day. This work was published as a series of articles in the Political Register and as a book, Rural Rides, in 1830.Cobbett continued to publish controversial material in the Political Register and in July, 1831, was charged with seditious libel after writing an article in support of the Captain Swing Riots. Cobbett conducted his own defence and he was so successful that the jury failed to convict him.

William Cobbett still had a strong desire to be elected to the House of Commons. He was defeated in Preston in 1826 and Manchester in 1832 but after the passing of the 1832 Reform Act Cobbett was able to win the parliamentary seat of Oldham. In Parliament Cobbett concentrated his energies on attacking corruption in government and the 1834 Poor Law. William Cobbett died on 18th June 1835.

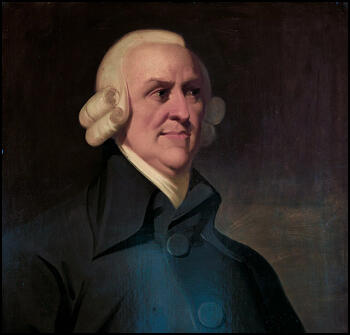

On this day in 1776 Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith is published. The book was an attempt to trace the historical development of industry and commerce in Europe. Smith examined the consequences of economic freedom and argued that it was the division of labour, rather than land or money, that was the main ingredient of economic growth. As he explained: "Every man is rich or poor according to the degree in which he can afford to enjoy the necessaries, conveniencies, and amusements of human life. But after the division of labour has once thoroughly taken place, it is but a very small part of these with which a man's own labour can supply him. The far greater part of them he must derive from the labour of other people, and he must be rich or poor according to the quantity of that labour which he can command, or which he can afford to purchase."

Adam Smith pointed out the dangers of a system that allowed individuals to pursue individual self-interest at the deteriment of the rest of society. He warned against the establishment of monopolies. "A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly understocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate."

Smith went onto argue: "People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary."

Smith argued that capitalism results in inequality. For example, he wrote about the impact poverty had on the lives of the labouring class: "It is not uncommon... in the Highlands of Scotland for a mother who has borne twenty children not to have two alive... In some places one half the children born die before they are four years of age; in many places before they are seven; and in almost all places before they are nine or ten. This great mortality, however, will every where be found chiefly among the children of the common people, who cannot afford to tend them with the same care as those of better station."

To protect the poor Adam Smith argued for government intervention: ""The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention in finding out expedients for removing difficulties which never occur. He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become. The torpor of his mind renders him not only incapable of relishing or bearing a part in any rational conversation, but of conceiving any generous, noble, or tender sentiment, and consequently of forming any just judgment concerning many even of the ordinary duties of private life... But in every improved and civilized society this is the state into which the labouring poor, that is, the great body of the people, must necessarily fall, unless government takes some pains to prevent it."

In the Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations Smith argues that progressive taxation is a vital ingredient in the creation of a fair society: "The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state. The expense of government to the individuals of a great nation is like the expense of management to the joint tenants of a great estate, who are all obliged to contribute in proportion to their respective interests in the estate. In the observation or neglect of this maxim consists what is called the equality or inequality of taxation.

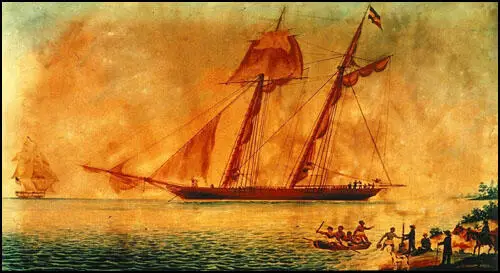

On this day in 1841 the U.S. Supreme Court rules on the Amistad case. In 1839 Jose Ruiz purchased 49 slaves in Havana, Cuba. With his friend, Pedro Montez, who had acquired four new slaves, Ruiz hired Ramon Ferrer to take them in his schooner Amistad, to Puerto Principe, a settlement further down the coast.

On 2nd July, 1839, the slaves, led by Joseph Cinque, killed Ramon Ferrer, and took possession of his ship. Cinque ordered the navigator to take them back to Africa but after 63 days at sea the ship was intercepted by Lieutenant Gedney and the United States brig Washington, half a mile from the shore of Long Island. The Amistad was then towed into New London, Connecticut.

Joseph Cinque and the other Africans were imprisoned in New Haven. James Covey, a sailor on a British ship, was employed to interview the Africans to discover what had taken place. The Spanish government insisted that the mutineers be returned to Cuba. President Martin van Buren was sympathetic to these demands but insisted that the men would be first tried for murder.

Lewis Tappan and James Pennington took up the African's case and argued that while slavery was legal in Cuba, importation of slaves from Africa was not. The judge agreed, and ruled that the Africans had been kidnapped and had the right to use violence to escape from captivity.

The United States government appealed against this decision and the case appeared before the Supreme Court. The former president, John Quincy Adams, was so moved by the plight of Joseph Cinque and his fellow Africans, that he volunteered to represent them. Although now seventy-three, his passionate eight-hour speech won the argument and the mutineers were released.

Lewis Tappan and the anti-slavery movement helped fund the return of the 35 surviving Africans to Sierra Leone. They arrived in January, 1842, along with five missionaries and teachers who formed a Christian anti-slavery mission in the country.

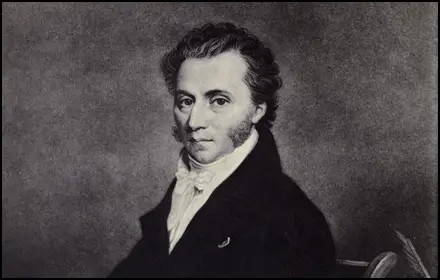

On this day in 1859 political activist Thomas Attwood died. Thomas Attwood, the son of Matthias and Ann Attwood, was born at Hawne House, Halesowen on 6th October, 1783. Matthias Attwood was a successful businessman who owned extensive coal and iron interests in Halesowen and a bank in Birmingham. After being educated at Wolverhampton Grammar School, Thomas Attwood began work at his father's bank.

Attwood first became involved in politics when he joined the campaign against the East India Company. Attwood believed that the actions of the company was severely restricting foreign trade. As many local businesses depended on the export trade, the East India Company was blamed for the growing unemployment in Birmingham.

In 1812 the government appointed a Select Committee to of the House of Commons to investigate the activities of the East India Company. Attwood led the Birmingham delegation which gave evidence to the Committee. Attwood was a very impressive witness and his evidence was partly responsible for convincing the House of Commons to restrict the company's monopoly of foreign trade.

Thomas Attwood now began to take an interest in economic matters and in 1815 he put forward a policy that he believed would reduce unemployment. Attwood argued that Britain should have a paper currency which was not tied to gold. His second theory was that the government should counter economic depressions by increasing the money supply.

Attwood's economic theories were popular in Birmingham but he failed to convince the government. Although he managed to persuade 40,000 people to sign a petition advocating currency reform, the Duke of Wellington and his government refused to consider Attwood's proposal. Attwood gradually developed the view that the House of Commons needed more people with business experience and knowledge of economics. He therefore joined the demand for large manufacturing towns like Birmingham to be represented in Parliament.

On 25th January, 1830, about 10,000 people attended the first meeting of the Birmingham Political Union. People listened for six hours to speeches made by Attwood and other leaders of the organisation. Another meeting in May at the Beardsworth Repository in Birmingham was attended by over 80,000 people. Other manufacturing towns in Britain began to follow Birmingham's example and formed Political Unions.

For the next two years Attwood was one of the main leaders in the campaign for parliamentary reform. When the Reform Act was eventually passed in 1832, Attwood was installed as a freeman of the City of London in recognition of the important role he had played in the fight for the vote. In the general election held in the autumn of 1832 Attwood and another leading member of the Political Union, Joshua Scholefield, were elected unopposed as Birmingham's first two MPs.

Attwood worked hard to convince the House of Commons of the wisdom of his economic ideas. However, he was unsuccessful at persuading his fellow MPs and he eventually came to the conclusion that a further reform of Parliament was needed. In May, 1837, the Birmingham Political Union was revived. In June a new list of demands were drawn up, including: currency reform, household suffrage, triennial parliaments, payment of MPs, and the abolition of the property qualification.

In January 1838 Thomas Attwood and the Birmingham Political Union began to work with the London Working Men's Association in the fight for the vote. However, Attwood objected to the aggressive speeches made by Feargus O'Connor and was much more closely aligned with William Lovett, Henry Hetherington, John Cleave and the other Moral Force Chartists.

In June 1839, Attwood presented the first National Petition to the House of Commons. Although it had been signed by over 1,280,000 people, the Commons rejected the petition by 235 votes to 46. Frustrated by the unwillingness of Parliament to respond to public pressure, and aware that many of the Chartist leaders had doubts about currency reform, Attwood decided to resign from Parliament. Attwood took no further part in politics. In later life Attwood suffered from creeping paralysis.

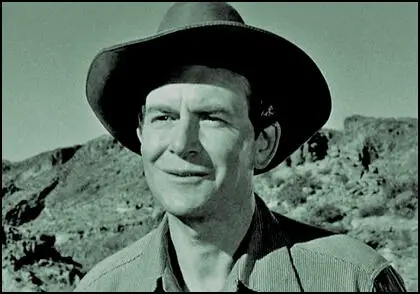

On this day in 1902 blacklisted actor Will Geer was born in Frankfort, Indiana. After graduating from Columbia University he joined the Group Theatre. Established in New York by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg in 1931. The Group was a pioneering attempt to create a theatre collective, a company of players trained in a unified style and dedicated to presenting contemporary plays.

Others involved in the group included Elia Kazan, Stella Adler, John Garfield, Luther Adler, Howard Da Silva, Franchot Tone, John Randolph, Joseph Bromberg, Michael Gordon, Clifford Odets and Lee J. Cobb. Members of the group tended to hold left-wing political views and wanted to produce plays that dealt with important social issues.

One of Geer's most important roles was in The Cradle Will Rock, an anti-capitalist musical by Marc Blitzstein. Developed within the Federal Theatre Project, the original production, with Orson Welles, John Houseman and Howard da Silva was banned for political reasons. It eventually was performed at the Mercury Theatre.

In 1934, Will Gere met Herta Ware at a maritime union benefit and the pair were married. Ware also had socialist views and was the granddaughter of Ella Reeve Bloor, who in 1897 she joined with Eugene Debs and Victor Berger to form the Social Democratic Party (SDP). The following year she moved to the more radical Socialist Labor Party that was led by Daniel De Leon.

After appearing in several successful Group Theatre plays, Geer moved to Hollywood and appeared in films such as The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935), The Fight for Life (1940), Deep Waters (1948), Lust for Gold (1949), Convicted (1950) and Broken Arrow (1950).

Geer had been active in radical political organizations in the 1930s and 40s. When he refused to testify before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) about the political views of other people in the cinema industry, he was blacklisted.

Herta Ware, Geer's wife, described the impact of the blacklist on her husband and his friends in her book, Fantastic Journey: My Life with Will Geer (2000): "Many a blacklisted writer has functioned fully with his blacklisted label covered by a pseudonym. Some of the industry's finest lived for years abroad or in the shadows, their economic survival assured. But actors, wholly dependent on their faces, voices and their whole presence, have nowhere to hide. They were cut off in their prime. It is one of many American Tragedies."

Unable to work in Hollywood or in television, Geer returned to the stage. He formed the Theatricum Botanicum, a repertory company in California. As well as producing plays, Geer was involved in organizing discussion groups and folksinging concerts.

After the blacklist was lifted, Greer appeared as Granpa Zeb Walton in the long-running television series, The Waltons (1972-78). Will Geer died in Los Angeles on 22nd April, 1978.

On this day in 1915 Johnnie Johnson was born at Barrow-upon-Soar, Leicestershire, England. He studied at Loughborough College and Nottingham University but after being rejected by the Royal Air Force he became a civil engineer.

Johnson was also initially rejected by the RAF Volunteer Reserve but they changed their mind after the outbreak of the Second World War. Selected for pilot training he was sent to Hawarden in Cheshire to learn to fly the Supermarine Spitfire.

In September, 1940, Johnson was posted to 19 Squadron but missed most of the Battle of Britain after being forced to have an operation on his shoulder. When he recovered he joined 616 Squadron where he flew Douglas Bader, Hugh Dundas and Jeff West.

Johnson soon emerged as an outstanding fighter pilot. A master of accurate deflection shooting, a skill he had developed as a child when he hunted rabbits with a shotgun. In September 1941 Johnson was promoted to flight lieutenant and was given command of B Flight.

In 1942 Johnson became squadron leader and in March 1943 was promoted to wing commander and given command of 610 Squadron. The following year he took over the Canadian wing in the recently formed 2nd Tactical Air Force.

By the end of the Second World War Johnson had flown in over 1,000 combat missions. He holds the remarkable record of never being shot down and on only one occasion was his Spitfire damaged by the enemy. Johnson has been credited with 38 kills. Officially this is the highest total of any RAF pilot but some experts believe that Marmaduke Pattle scored more than 40.

Johnson, who was awarded the DSO and two bars, the DFC and bar, the Legion d'Honneur and the Croix de Guerre, stayed in the Royal Air Force after the war. He served with the United States Air Force in the Korean War where he was awarded the American DFC.

In 1960 Johnson was appointed senior air staff officer in 3 Group, Bomber Command. He eventually retired in 1966 as Air Officer Commanding, Air Forces Middle East in Aden.

Johnnie Johnson, who lived for a while in Jersey before retiring to Buxton, Derbyshire, died on 30th January, 2001.

On this day in 1918 Frank Wedekind died from complications during surgery in Munich. Benjamin Franklin Wedekind, the second of the six children born to Friedrich Wilhelm Wedekind, a physician, and Emilie Kammerer, a German singer and actress, was born in Hanover on 24th July, 1864. The family moved to Lenzburg in Switzerland, where his father had purchased a castle.

In 1884 Wedekind entered the University of Lausanne, and then moved to the University of Munich. He studied law and literature, but abandoned his studies and took a job as a publicity agent for the Swiss soup company Maggi.

Wedekind eventually returned to Munich where he attempted to make a living from acting. Wedekind also wrote plays and in 1891 he produced Spring Awakening. The sexual content of the play created great controversy and was immediately banned in Germany due to its frank portrayal of abortion, homosexuality, rape, child abuse and suicide. According to the authors of the The Concise Oxford Companion to the Theatre: "The play harks back to Büchner in its staccato structure and intensified realism, but looks forward to Expressionism and Symbolism in its grave-yard and schoolroom scenes in which it analyses the situation of two 14-year-old lovers who pay with their lives for the moral dishonesty of their tyrannical parents."

Dennis Kennedy has added: "Containing scenes of homosexual love, masturbation, and flagellation, the piece is a disturbing condemnation of how an oppressive society deals with puberty. Its provocative content, episodic structure, abrupt language, and two-dimensional and symbolic characters, like the Man-in-the-Mask played at its première by the author, all anticipate expressionism."

In 1896 Albert Langen, the son of a Rhineland industrialist, started the left-wing journal, Simplicissimus. Wedekind was an early contributor to the journal. Others writers and artists involved in the project included Thomas Heine, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, Olaf Gulbransson, Rudolf Wilke, Walter Trier and Edward Thony. The journal constantly attacked the German establishment. One right-wing journal in Germany, Augsburger Postzeitung, complained about the influence that it was having on young students and called for it to be banned as is was creating a "real danger to school discipline".

Wedekind's next play, Earth Spirit, was produced in Leipzig on 25th February 1898. This was the first of his "Lulu plays", which have as their central figure Lulu, a purely sexual creature who drives men to ruin. According to one critic: "Finally she meets her nemesis by being murdered by Jack the Ripper, one creature of instinct destroyed by another." Wedekind admitted that "she was created to stir up great disaster. "

Later that year Kaiser Wilhelm II objected to an article by Wedekind and a cartoon by Thomas Heine that appeared in the journal during his visit to Palestine. The issue was confiscated and a lawsuit was brought against Wedekind, Heine and the publisher, Albert Langen. Following the advice of his lawyer, Langen fled to Switzerland and remained in exile for five years. Both Wedekind (seven months) and Heine (six months) were imprisoned in the fortress of Köningstein for their attack on the German monarchy.

Wedekind developed a reputation for promiscuous behaviour and had an affair with Frida Uhl, the former wife of August Strindberg. She eventually gave birth to his child. He mixed with a group of bohemian artists and political activists including Erich Mühsam, who was a strong advocate of free love.

On the stage Wedekind often collaborated with the young Austrian actress Tilly Newes. They acted together in the second of his Lulu plays, Pandora's Box, in Vienna, at a private performance in 1905. Tilly played Lulu and Wedekind took the role of Jack the Ripper. The writer Karl Kraus played Kung Poti.

It has been argued that Wedekind "deliberately sought to outrage bourgeois society" and that he reflected the "perceived threat of powerful women" current at the time. In 1906, Wedekind married Newes, 22 years his junior. He rejected his previous promiscuous behaviour and became intensely jealous of his young wife.

The theatre critic, John Simon, has pointed out: "Wedekind acted in his plays and performed his cabaret songs with a quirky but insidious individuality, and championed freedom of expression, women's rights, anti-anti-Semitism and other worthy causes. His drama was the fountainhead of not just one form of German modernism, but of all three movements that superseded naturalism: Symbolism, Expressionism and that tertium quid whose creator, Bertolt Brecht, acknowledged him as his master."

Frank Wedekind died from complications during surgery in Munich on 9th March, 1918.

On this day in 1933 President Franklin D. Roosevelt called a special session of Congress. He told the members that unemployment could only be solved "by direct recruiting by the Government itself." For the next three months, Roosevelt proposed, and Congress passed, a series of important bills that attempted to deal with the problem of unemployment. The special session of Congress became known as the Hundred Days and provided the basis for Roosevelt's New Deal.

The draft legislation was finished on 14th May. It went before Congress and the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) was passed by the Senate on 13th June by a vote of 46 to 37. The National Recovery Administration (NRA) was set up to enforce the NIRA. President Franklin D. Roosevelt named Hugh S. Johnson to head it. Roosevelt found Johnson's energy and enthusiasm irresistible and was impressed with his knowledge of industry and business. William E. Leuchtenburg has commented: "A gruff, pugnacious martinet with the leathery face and order-barking rasp of a former cavalry officer, Johnson had no illusions about the dimensions of the job."

Johnson expected to run the whole of the NRA. However, Roosevelt decided to split it into two and placed the Public Works Administration (PWA) with its 3.3 billion dollar public works programme, under the control of Harold Ickes. When he heard the news Johnson stormed out of the cabinet meeting. Roosevelt sent Frances Perkins after him and she eventually persuaded him not to resign.As David M. Kennedy has pointed out in Freedom from Fear (1999), the NRA and the PWA "were to be like two lungs, each necessary for breathing life into the moribund industrial sector".

Jean Edward Smith, the author of FDR (2007): "No two appointees could have been more dissimilar, and no two less likely to cooperate. For Johnson, an old cavalryman, every undertaking was a hell-for-leather charge into the face of the enemy. Ickes, on the other hand, was pathologically prudent. As he saw it, the problem of the public works program was not to spend money quickly but to spend it wisely. Obsessively tightfisted, personally examining every project in minute detail, Ickes spent a minuscule $110 million of PWA money in 1933."

The National Recovery Act allowed industry to write its own codes of fair competition but at the same time provided special safeguards for labor. Section 7a of NIRA stipulated that workers should have the right to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing and that no one should be banned from joining an independent union. The NIRA also stated that employers must comply with maximum hours, minimum pay and other conditions approved by the government. Johnson asked Roosevelt if Donald R. Richberg could be general counsel of the NRA. Roosevelt agreed and on 20th June, 1933, Roosevelt appointed him to the post. Richberg's main task was to implement and defend Section 7(a) of the NIRA.

Employers ratified these codes with the slogan "We Do Our Part", displayed under a Blue Eagle at huge publicity parades across the country, Franklin D. Roosevelt used this propaganda cleverly to sell the New Deal to the public. At a Blue Eagle parade in New York City a quarter of a million people marched down Fifth Avenue. Roosevelt argued that "there is a unity in this country which I have not seen and you have not seen since April, 1917."

The NRA program was voluntary. However, those businessmen who accepted the codes developed by the various trade associations, could place the NRA blue eagle symbol in their windows and on the packaging of their goods. This virtually made the scheme compulsory as those companies that did not display the NRA symbol were seen as unpatriotic and selfish.

Johnson's first success was with the textile industry. This included bringing an end to child labour. As William E. Leuchtenburg, the author of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal (1963), has pointed out: "At the dramatic cotton-code hearing, the room burst into cheers when textile magnates announced their intention to abolish child labor in the mills. In addition, the cotton textile code stipulated maximum hours, minimum wages, and collective bargaining." As Johnson pointed out: "The Textile Code had done in a few minutes what neither law nor constitutional amendment had been able to do in forty years."

On 30th June, 1933, Hugh S. Johnson commented: "You men of the textile industry have done a very remarkable thing. Never in economic history have labor, industry, government and consumers' representatives sat together in the presence of the public to work out by mutual agreement a 'law merchant' for an entire industry... The textile industry is to be congratulated on its courage and spirit in being first to assume this patriotic duty and on the generosity of its proposals." However, some trade unionists criticized the agreement to a $11 minimum wage as a "bare subsistence wage" that would provide workers with little more than "an animal existence."

By the end of July 1933 Johnson had half the main ten industries, textiles, shipbuilding, woolens, electricals and the garment industry, signed up. This was followed by the oil industry but he was forced to make a raft of concessions on price policy to persuade the steel industry to join. On 27th August, the automobile manufactures, except for Henry Ford, agreed terms with Johnson. When the coal operators fell in line on 18th September, Johnson had won the last of the big ten industries to the NRA in a period of only three months.

The coal code brought dramatic gains for miners. It included the right of miners to a checkweighman and payment on a net-ton basis and prohibitions against child labour, compulsory scrip wages and the compulsory company store. It also meant higher wages. As a result of the agreement, the United Mine Workers increased union membership from 100,000 to 300,000.

Ford announced he intended to meet the wage and hour provision of the code or even to improve on them. However, he refused to sign up to the code. Johnson reacted by urging the public not to purchase Ford vehicles. He also told the federal government not to purchase vehicles from Ford dealers. Johnson commented: "If we weaken on this, it will greatly harm the Blue Eagle principle and campaign." Johnson's actions resulted in a decline in sales of Ford cars and trucks in 1933. However, it only had a short-term impact and in 1934 the company had increased sales and profits.

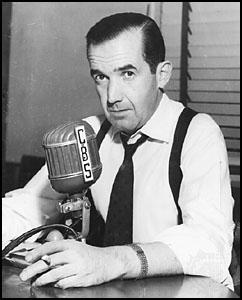

On this day in 1954 Ed Murrow presented an CBS See It Now programme, dealt with McCarthyism. During the broadcast Murrow commented: "The line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one and the junior Senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep into our own history and our doctrine and remember that we are not descended from fearful men, not men who feared to write, to speak, to associate, and to defend causes which were for the moment unpopular. This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthty's methods to keep silent. We can deny our heritage and our history, but we cannot escape responsibility for the result."

The day after the programme CBS announced that 12,348 people phoned in comments about the programme, and the opinions went fifteen-to-one in Murrow's favor. The sponsors also reported receiving over 4,000 letters, with the vast majority supporting Murrow's stance. The New York Herald Tribune, a Republican newspaper, said Murrow had presented "a sober and realistic appraisal of McCarthyism and the climate in which it flourishes." Jack Gould, television critic for The New York Times, called the broadcast "crusading journalism of high responsibility and genuine courage", an "incisive visual autopsy of the Senator's record'. However, Jack O'Brian, radio-TV columnist for Hearst's right-wing New York Journal-American, labelled the broadcast a "smear".

When Joe McCarthy was asked what he thought of the programme he replied: "I never listen to the extreme left-wing, bleeding heart elements of radio and TV." Several times over the next few days he attacked Murrow. He claimed that Murrow had "sponsored a communist school in Moscow" and "acted for the Russian espionage and propaganda organization known as VOKS, a job which would normally be done by the Russian secret police." He claimed that Murrow's friendship with Harold Laski, a leading figure in the British Labour Party, was an example of his pro-Communist sympathies.

The persecution of those opposed to McCarthyism continued. When the See It Now programme ended on 9th March, Don Hollenbeck, came on the air with the regular 11.00 p.m. news and said: "I want to associate myself with every word just spoken by Ed Murrow." Hollenbeck was denounced in the pro-McCarthy press as a communist. After three months of smears, Hollenbeck, unable to take the strain, committed suicide.

McCarthy's downfall came as a result of the televised senate investigations into the United States Army. One newspaper, the Louisville Courier-Journal, reported that: "In this long, degrading travesty of the democratic process McCarthy has shown himself to be evil and unmatched in malice." Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22.