Amistad Mutiny

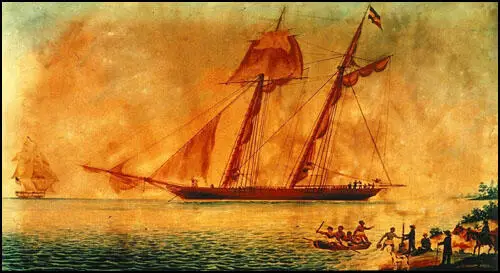

In 1839 Jose Ruiz purchased 49 slaves in Havana, Cuba. With his friend, Pedro Montez, who had acquired four new slaves, Ruiz hired Ramon Ferrer to take them in his schooner Amistad, to Puerto Principe, a settlement further down the coast.

On 2nd July, 1839, the slaves, led by Joseph Cinque, killed Ramon Ferrer, and took possession of his ship. Cinque ordered the navigator to take them back to Africa but after 63 days at sea the ship was intercepted by Lieutenant Gedney and the United States brig Washington, half a mile from the shore of Long Island. The Amistad was then towed into New London, Connecticut.

Joseph Cinque and the other Africans were imprisoned in New Haven. James Covey, a sailor on a British ship, was employed to interview the Africans to discover what had taken place. The Spanish government insisted that the mutineers be returned to Cuba. President Martin van Buren was sympathetic to these demands but insisted that the men would be first tried for murder.

Lewis Tappan and James Pennington took up the African's case and argued that while slavery was legal in Cuba, importation of slaves from Africa was not. The judge agreed, and ruled that the Africans had been kidnapped and had the right to use violence to escape from captivity.

The United States government appealed against this decision and the case appeared before the Supreme Court. The former president, John Quincy Adams, was so moved by the plight of Joseph Cinque and his fellow Africans, that he volunteered to represent them. Although now seventy-three, his passionate eight-hour speech won the argument and the mutineers were released.

Lewis Tappan and the anti-slavery movement helped fund the return of the 35 surviving Africans to Sierra Leone. They arrived in January, 1842, along with five missionaries and teachers who formed a Christian anti-slavery mission in the country.

Slavery in the United States (£1.29)

Primary Sources

(1) Details of the Amistad Mutiny was provided to the Supreme Court in January 1841.

On the 27th of June 1839, the schooner Amistad, being the property of Spanish subjects, cleared out from the port of Havana, in the island of Cuba, for Puerto Principe, in the same island. On board of the schooner were the master, Ramon Ferrer, and Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montez, all Spanish subjects. The former had with him a negro boy, named Antonio, claimed to be his slave. Jose Ruiz had with him forty-nine negroes, claimed by him as his slaves, and stated to be his property, in a certain pass or document, signed by the governor-general of Cuba. Pedro Montez had with him four other negroes, also claimed by him as his slaves, and stated to be his property, in a similar pass or document, also signed by the governor- general of Cuba. On the voyage, and before the arrival of the vessel at her port of destination, the negroes rose, killed the master, and took possession of her.

On the 26th of August, the vessel was discovered by Lieutenant Gedney, of the United States brig Washington, at anchor on the high seas, at the distance of half a mile from the shore of Long Island. A part of the negroes were then on shore, at Culloden Point, Long Island; who were seized by Lieutenant Gedney, and brought on board. The vessel, with the negroes and other persons on board, was brought by Lieutenant Gedney into the district of Connecticut, and there libelled for salvage in the district court of the United States.

On the 18th of September, Ruiz and Montez filed claims and libels, in which they asserted their ownership of the negroes as their slaves, and of certain parts of the cargo, and prayed that the same might be 'delivered to them, or to the representatives of her Catholic Majesty, as might be most proper.'

(2) Statement signed by Jose Ruiz (August, 1839)

I bought 49 slaves in Havana, and shipped them on board the schooner Amistad. We sailed for Guanaja, the intermediate port for Principe. For the four first days every thing went on well. In the night heard a noise in the forecastle. All of us were asleep except the man at the helm. Do not know how things began; was awoke by the noise. This man Joseph, I saw. Cannot tell how many were engaged. There was no moon. It was very dark. I took up an oar and tried to quell the mutiny; I cried no! no! I then heard one of the crew cry murder. I went below and called on Montez to follow me, and told them not to kill me: I did not see the captain killed.

They called me on deck, and told me I should not be hurt. I asked them as a favor to spare the old man. They did so. After this they went below and ransacked the trunks of the passengers. Before doing this, they tied our hands. We went on our course--don't know who was at the helm. Next day I missed Captain Ramon Ferrer, two sailors, Manuel Pagilla, and Yacinto, and Selestina, the cook. We all slept on deck. The slaves told us next day that they had killed all; but the cabin boy said they had killed only the captain and cook. The other two he said had escaped in the small boat.

(3) Statement signed by Antonio, the cabin boy on the Amistad (August, 1839)

We had been out four days when the mutiny broke out. That night it had been raining very hard, and all hands been on deck. The rain ceased, but still it was very dark. Clouds covered the moon. After the rain, the Captain and mulatto lay down on some matresses that they had brought on deck. Four of the slaves came out, armed with those knives which are used to cut sugar cane; they struck the Captain across the face twice or three times; they struck the mulatto oftener. Neither of them groaned. By this time the rest of the slaves had come on deck, all armed in the same way. The man at the wheel and another let down the small boat and escaped. I was awake and saw it all. The men escaped before Senor Ruiz and Senor Montez awoke.

Joseph, the man in irons, was the leader; he attacked Senor Montez. After killing the Captain and the cook, and wounding Senor Montez, they tied Montez and Ruiz by the hands till they had ransacked the cabin. After doing so, they loosed them, and they went below. Senor Montez could scarcely walk. The bodies of the Captain and mulatto were thrown overboard and the decks washed. One of the slaves who attacked the Captain has since died.

(4) Statement signed by Pedro Montez (August, 1839)

We left Havana on the 28th of June. I owned 4 slaves, 3 females and 1 male. For three days the wind was ahead and all went well. Between 11 and 12 at night, just as the moon was rising, sky dark and cloudy, weather very rainy, on the fourth night I laid down on a matress. Between three and four was awakened by a noise which was caused by blows given to the mulatto cook. I went on deck, and they attacked me. I seized a stick and a knife with a view to defend myself. I did not wish to kill or hurt them. At this time the prisoner wounded me on the head severely with one of the sugar knives, also on the arm. I then ran below and stowed myself between two barrels, wrapped up in a sail. The prisoner rushed after me and attempted to kill me, but was prevented by the interference of another man. I recollect who struck me, but was not sufficiently sensible to distinguish the man who saved me. I was faint from loss of blood. I then was taken on deck and tied to the hand of Ruiz.

After this they commanded me to steer for their country. I told them I did not know the way. I was much afraid, and had lost my senses, so I cannot recollect who tied me. On the second day after the mutiny, a heavy gale came on. I still steered, having once been master of a vessel. When recovered, I steered for Havana, in the night by the stars, but by the sun in the day, taking care to make no more way than possible. After sailing fifty leagues, we saw an American merchant ship, but did not speak her. We were also passed by a schooner but were unnoticed. Every moment my life was threatened.

I know nothing of the murder of the Captain. Next morning the negroes had washed the decks. During the rain the Captain was at the helm. They were all glad, next day, at what had happened. The prisoners treated me harshly, and but for the interference of others, would have killed me several times every day. We kept no reckoning. I did not know how many days we had been out, nor what day of the week it was when the officers came on board. We anchored at least thirty times, and lost an anchor at New Providence. When at anchor we were treated well, but at sea they acted very cruelly towards me. They once wanted me to drop anchor in the high seas. I had no wish to kill any of them, but prevented them from killing each other.

(5) The New York Morning Herald reported that one of its readers had visited Joseph Cinque in prison ( Sept. 18, 1839)

Instead of a chivalrous leader with the dignified and graceful bearing of Othello, imparting energy and confidence to his intelligent and devoted followers, he saw a sullen, dumpish looking negro, with a flat nose, thick lips, and all the other characteristics of his debased countrymen, without a single redeeming or striking trait, except the mere brute qualities of strength and activity, who had inspired terror among his companions by the indiscriminate and unsparing use of the lash. And instead of intelligent and comparatively civilized men, languishing in captivity and suffering under the restraints of the prison, he found them the veriest animals in existence, perfectly contented in confinement, without a ray of intelligence, and sensible only to the wants of the brute.

No man, he said, more thoroughly appreciated the hideous horrors of the slave trade, or had conceived a more decided aversion to slavery in all its phases; but he was certain that the natives of Africa would be improved and elevated by transferring them to the genial climate of Carolina, and the mild restraints of an intelligent and humane planter.

(6) Report of Joseph Cinque's testimony in court, New York Journal of Commerce (10th January, 1840)

Cinque, the leader of the Africans, was then examined. Cinque told Captain Gedney he might take the vessel and keep it, if he would send them to Sierra Leone. His conversation with Captain Gedney was carried on by the aid of Bernar, who could speak a little English. They had taken on board part of their supply of water, and wanted to go to Sierra Leone. They were three and a half months coming from Havana to this country.

Cross examined by General Isham. Cinque said he came from Mendi. He was taken in the road where he was at work, by countrymen. He was not taken in battle. He did not sell himself. He was taken to Lomboko, where he met the others for the first time. Those who took him - four men - had a gun and knives. Has three children in Africa. Has one wife. Never said he had two wives. Can't count the number of days after leaving Havana before the rising upon the vessel. The man who had charge of the schooner was killed. Then he and Pepe sailed the vessel. Witness told Pepe, after Ferrer was killed, to take good care of the cargo.

The brig fired a gun, and then they gave themselves up. When they first landed there they were put in prison. Were not chained. They were chained coming from Africa to Havana, hands and feet. They were chained also on board the Amistad. Were kept short of provisions. Were beaten on board the schooner by one of the sailors. When they had taken the schooner they put the Spaniards down in the hold and locked them down.