On this day on 5th January

On this day in 1066 Edward the Confessor died. Edward, the seventh son of Ethelred the Unready, king of England, was born in Islip in Oxfordshire in about 1003. Edward's mother, Emma of Normandy, was the daughter of Richard, Duke of Normandy.

After the death of Ethelred the Unready in 1016, the throne of England passed to Canute the Great. The new king married Emma of Normandy and the couple had a son, Hardicanute.

Edward spent the first part of his life in Normandy. He held deep religious convictions and became known as Edward the Confessor. When Hardicanute became king of England in 1040, he recalled his half-brother to the English court.

In 1042, Hardicanute died of convulsions at a drinking party. Edward now became king and one of his first acts was to deprive his mother, Emma of Normandy, of all her estates. Anglo-Saxon chroniclers claimed that Edward had done this because he felt he had been neglected by his mother as a child.

For the first years of his reign English political life was dominated by Godwin of Wessex, Leofric of Mercia and Siward of Northumbria. Godwin became the most important of these when Edward married his daughter Edith in 1045. Godwin hoped that his daughter would have a son but Edward had taken a vow of celibacy and it soon became clear that the couple would not produce an heir to the throne.

In 1051 a group of Normans became involved in a brawl at Dover and several men were killed. The king ordered Godwin, as earl of Wessex, to punish the people of Dover for this attack on his Norman friends. Godwin refused and instead raised an army against the king. The earls of Mercia and Northumbria remained loyal to Edward and to avoid a civil war, Godwin and his family agreed to go into exile.

Over the next year Edward the Confessor increased the number of Norman advisers in England. This upset the Anglo-Saxons and when Godwin and a large army commandeered by his sons, Harold and Tostig, landed in the south of England in 1052, Edward was unable to raise significant forces to stop the invasion.

Godwin now forced Edward to send his Norman advisers home. Godwin was also given back his family estates and was now the most powerful man in England. When Godwin died the following year, his place as the leading Anglo-Saxon in England was taken by his son Harold of Wessex .

Edward the Confessor and Edith did not have any children. William of Normandy claimed that at a meeting in 1051 Edward had promised him that he would become his heir. Edward's legitimate heir was his grandson, Edgar Atheling. However, on Edward's deathbed in 1066, it is claimed that he nominated Harold of Wessex, as the successor to the throne.

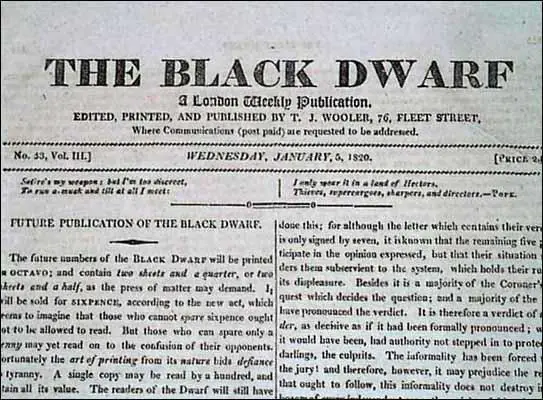

On this day in 1817 Thomas Jonathan Wooler published the first issue of Black Dwarf, a new radical unstamped journal. It was an eight page newspaper but it later became a 32 page pamphlet and cost 4d. (1)

Wooler argued that the real freedom of Englishmen lay in their power and their will to uphold their liberties, not throught the Constitution which was simply the "recorded merits of our ancestors", but by deeds. He warned "the higher orders think the best mode is to destroy the Constitution altogether and then their cause can run no further risk."

This was a period of time it was possible to make a living from being a radical publisher. "The means of production of the printed page were sufficiently cheap to mean that neither capital nor advertising revenue gave much advantage; while the successful Radicalism, for the first time, a profession which could maintain its own full-time agitators."

James Epstein has pointed out: "The Black Dwarf was one of the most influential radical journals of the post-war years. The journal's tone was satiric; its politics were those of radical constitutionalism. Wooler was a gifted writer known for his habit of directly typesetting his articles without first committing them to writing. Among his contributions to the journal were regular letters from the character named the Black Dwarf to various fictional correspondents."

Within a few months it reached a circulation of 12,000 and received the backing of the reform movement's senior politician, Major John Cartwright. The newspaper gave its support to Cartwright's Hampden Clubs. Cartwright main objective was to unite middle class moderates with radical members of the working class. It has been argued by E. P. Thompson that during this period Wooler became one of the main leaders of the reform movement.

Wooler compared these clubs to the work of the Quakers: "Those who condemn clubs either do not understand what they can accomplish, or they wish nothing to be done... Let us look at, and emulate the patient resolution of the Quakers. They have conquered without arms - without violence - without threats. They conquered by union."

Thomas Wooler was arrested in early May 1817 and faced two trials for seditious libel for two articles published in the third and tenth numbers of the Black Dwarf. Wooler was tried at Guildhall before Justice Charles Abbott and two special juries on 5th June. The attorney-general, Samuel Shepherd, led the prosecution. Wooler defended himself brilliantly, with advice from Charles Pearson, the young City radical. He was eventually acquitted of the charges.

Wooler joined forces with William Cobbett to attack Robert Owen who was attempting to create a model community in New Lanark. In August 1817, Wooler wrote: "It is very amusing to hear Mr Owen talk of re-moralizing the poor. Does he not think that the rich are a little more in want of re-moralizing; and particularly that class of them that has contributed to demoralize the poor, if they are demoralized, by supporting measures which have made them poor, and which now continue them poor and wretched? Talk of the poor being demoralized! It is their would-be masters that create all the evils that afflict the poor, and all the depravity that pretended philanthropists pretend to regret."

Wooler went on to argue that the real problem was capitalism: "Let him abandon the labourer to his own protection; cease to oppress him, and the poor man would scorn to hold any fictitious dependence upon the rich. Give him a fair price for his labour, and do not take two-thirds of a depreciated remuneration back from him again in the shape of taxes. Lower the extravagance of the great. Tax those real luxuries, enormous fortunes obtained without merit. Reduce the herd of locusts that prey upon the honey of the hive, and think they do the bees a most essential service by robbing them. The working bee can always find a hive. Do not take from them what they can earn, to supply the wants of those who will earn nothing. Do this; and the poor will not want your splendid erections for the cultivation of misery and the subjugation of the mind."

It is estimated that 18 people were killed and about 500 were wounded during a meeting calling for parliamentary reform on 16th August, 1819. After the Peterloo Massacre, the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, sent a letter of congratulations to the Manchester magistrates for the action they had taken. He also sent a letter to Lord Liverpool, the Prime Minister, arguing that the government needed to take firm action.

When Parliament reassembled on 23rd November, 1819, Sidmouth announced details of what later became known as the Six Acts. The main objective of this legislation was the "curbing radical journals and meeting as well as the danger of armed insurrection".

Thomas Jonathan Wooler was arrested for taking part in the campaign to elect Sir Charles Wolseley to represent Birmingham in the House of Commons. As Birmingham had not been given permission to have an election, Wooler and his fellow campaigners were charged with "forming a seditious conspiracy to elect a representative to Parliament without lawful authority". Wooler was found guilty and sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment.

On his release from prison Wooler modified the tome of the Black Dwarf in an effort to comply with the terms of the Six Acts. As a result he lost circulation of those like Richard Carlile, the editor of The Republican, who refused to reduce his radicalism. This was a successful strategy and he was able to outsell pro-government newspapers such as The Times.

To survive, Wooler had to rely on financial help from Major John Cartwright. However, on Cartwright's death on 23rd September 1824, he was forced to close the newspaper down. He wrote in the final edition that there was no longer a "public devotedly attached to the cause of parliamentary reform". Whereas in the past they had demanded reform, now they only "clamoured for bread".

On this day in 1835 suffragist Olympia Brown was born in Michigan. One of four children she was educated locally and became a schoolteacher when she was 15 years old.

After being refused entry to the University of Michigan because she was a woman, Brown was accepted by Antioch College. While studying at Antioch she heard a speech made by the anti-slavery campaigner, Francis Gage. Afterwards she reported that: "It was the first time I had heard a woman preach and the sense of victory lifted me up."

Brown graduated from Antioch in 1860 and after much resistance, managed to enter St. Lawrence Seminary. In June 1863, she became the first woman to be ordained as a minister of the church. Over the next few years Brown worked as a pastor in Marshfield, Weymouth, and Bridgeport.

A founder member of the New England Woman's Suffrage Association in 1867 she joined Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and Lucy Stone in Kansas where Negro suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote. However, both ideas were rejected at the polls.

In 1878, Brown, now president of National Woman Suffrage Association in Wisconsin, became the pastor at the Church of the Good Shepherd in Racine. Over the next few years she invited leading campaigners for women's suffrage, such as Julia Ward Howe, Susan B. Anthony and Mary Livermore to speak from the pulpit.

During the First World War Brown joined Alice Paul and Lucy Burns to form the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage (CUWS) and attempted to introduce the militant methods used by the Women's Social and Political Union in Britain. This included organizing huge demonstrations and the daily picketing of the White House. Over the next couple of years the police arrested nearly 500 women for loitering and 168 were jailed for "obstructing traffic".

In June, 1920, Brown, now aged eighty-five, was one of the women who took part in the march on the Republican Convention in Chicago. This was the last of the great suffrage demonstrations as the Nineteenth Amendment was passed two months later. Of the original campaigners, Brown was the only one who lived long enough to witness women being granted the vote. Olympia Brown died in Baltimore on 23rd October, 1926.

On this day in 1861 Ethel Bentham, the daughter of William Bentham, an inspector and later general manager of the Standard Life Assurance Company, and his wife, Mary Ann Hammond, was born in London. She grew up in Dublin and visited the slums of the city on charitable missions with her mother. It was these experiences that inspired her to become a doctor, as a means of helping the poor.

Bentham began her training at the London School of Medicine for Women at the age of almost thirty, and gained her certificate in medicine in 1893. The following year she studied in Paris and in Brussels, where she achieved the degree of MD in 1895. After a brief spell working in London hospitals she went into general practice in Newcastle upon Tyne.

In 1909 Bentham moved to London and shared a house in Holland Park with Marion Phillips. She joined the Fabian Society, the Labour Party, National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies and the Women's Labour League and became a Labour councillor in the London borough of Kensington. In 1911 she helped establish a pioneering baby clinic in North Kensington. The objective was to provide preventive medicine for mothers and babies.

In 1909 Bentham, Maud Pember Reeves and the Fabian Women's Group began a four year study of the daily lives of working-class families in Lambeth. Maud's biographer, Sally Alexander, has argued: "The Lambeth mothers' project, initiated by Maud, was prompted by the recognition that more infants died in the London slums than in Kensington or Hampstead... Forty-two families were selected from a lying-in hospital in Lambeth, London, to have weekly visits, medical examinations from Dr Ethel Bentham every two weeks, and 5s. to be paid to the mother for extra nourishment for three months before the birth of the baby and for one year afterwards. The money came from private donations, and the mothers wrote down their weekly expenditure. Eight families withdrew because the husbands objected to this weekly scrutiny. Eight other mothers who could not read or write dictated their sums to their husbands or children."

Bentham's biographer, C. V. J. Griffiths, has pointed out: "A commitment to the suffrage movement was increasingly overtaken by her involvement in labour politics, and from March 1910 she sat on the executive of the Women's Labour League, chairing the committee regularly from 1912 onwards; she also held office in the Fabian Society. When the Women's Labour League was absorbed into the Labour Party in 1918, Bentham came top of the women's ballot in elections to the national executive committee."

In the 1929 General Election Bentham was elected to represent the constituency of East Islington, at the age of sixty-eight. The Conservative Party won 8,664,000 votes, the Labour Party 8,360,000 and the Liberal Party 5,300,000. However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power.

The election of the Labour Government coincided with an economic depression and MacDonald was faced with the problem of growing unemployment. In January 1929, 1,433,000 people were out of work, a year later it reached 1,533,000. By March 1930, the figure was 1,731,000. In June it reached 1,946,000 and by the end of the year it reached a staggering 2,725,000. That month MacDonald invited a group of economists, including John Maynard Keynes, J. A. Hobson, George Douglas Cole and Walter Layton, to discuss this problem. However, he rejected all those ideas that involved an increase in public spending.

Bentham spoke in the House of Commons on a few occasions only, usually on matters relating to her experiences as a doctor and a magistrate, and she introduced a bill on married women's nationality in November 1930. However, she was suffering from poor health and she died at her home at 110 Beaufort Street, Chelsea, on 19th January 1931. She was therefore the first woman to die while a member of Parliament. She was cremated three days later at Golders Green.

Cynthia Mosley, Marion Phillips, Susan Lawrence, Edith Picton-Turberville,

Margaret Bondfield, Ethel Bentham, Ellen Wilkinson, Mary Hamilton and Jennie Lee.

On this day in 1939 social reformer Margaret Haley died in Chicago. Haley was born in Joliet, Illinois, on 15th November, 1861. Haley became a teacher in Chicago in 1876. An early member of the Chicago Teachers' Federation she became a full-time official in 1901.

In 1903 Haley joined with Mary Kenney O'Sullivan, Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, Helen Marot, Agnes Nestor, Florence Kelley and Sophonisba Breckinridge to form the Women's Trade Union League.

Haley was also president of the National Federation of Teachers and used this organization to help develop the more important National Education Association. Haley led a long campaign for state pensions for teachers and this was successfully introduced in Illinois in 1907.

Haley became an organizer with the American Federation of Teachers when it was established in 1916. She also wrote and published the Margaret Haley Bulletin (1915-31).

On this day in 1970 German scientist Max Born died. He was born into a Jewish family in Breslau, Germany, on 11th December, 1882. He studied physics at the University of Gottingen and obtained his doctorate in 1907.

Born became professor of physics at Frankfurt-am-Main (1919-21) before moving back to the University of Gottingen where he made it into the centre for theoretical physics.

Inspired by the work of Nils Bohr, Born attempted to seek a mathematical explanation for the quantum theory. In 1924 Born coined the term quantum mechanics and the following year worked with his student, Werner Heisenberg, to develop a system called matrix mechanics that accounted mathematically for the position and momentum of the electron in the atom.

Born was an opponent of Adolf Hitler and he left Germany when he came to power in 1933. He went to England where he became a lecturer at the University of Cambridge. Later he became professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh (1936-53).

After the Second World War he returned to Germany and in 1954 shared the Nobel prize with Walther Bothe for their work in the field of quantum physics.

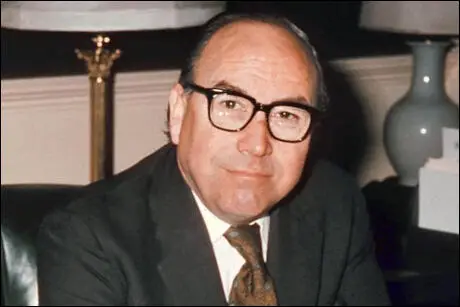

On this day in 2003 Roy Jenkins died. Jenkins was born in Abersychan, Monmouthshire, on 11th November, 1920. His father was Arthur Jenkins, president of the South Wales Miners' Federation and the Labour Party MP for Pontypool. Jenkins was educated at Abersychan Grammar School and Balliol College, Oxford, where he won a first in 1941.

According to John Campbell, the author of Roy Jenkins (2014), Jenkins had a homosexual relationship with Anthony Crosland, while at Oxford. The book claims that they had a "homosexual fling" and quotes Jenkins as telling Crosland that they had “an intense friendship of a kind that neither of us are ever likely to experience again”. They shared their time “in complete mutual absorption and complete mutual loyalty… wrapped up in our own two interwoven lives”.

During the Second World War Jenkins served in the Royal Artillery and for a while he worked as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park. In 1945 he married Jennifer Morris. Philip Johnston has argued: "Their homoerotic partnership (with Crosland) was broken by two events: the outbreak of war and Roy’s realisation that he preferred women, after meeting his future wife Jennifer, to whom he was married for 58 years. He would later become something of a Lothario, boasting many affairs, including with the wives of two of his closest friends."

A member of the Labour Party, Jenkins was elected to the House of Commons in 1948. At first he represented Central Southwark but at the 1950 General Election moved to Stechford, Birmingham. This was a time when the Conservative Party held power but Jenkins gradually became a leading figure in the shadow cabinet.

After the Labour Party won the 1964 GeneraI Election the new prime minister, Harold Wilson, appointed Jenkins as aviation minister. The following year, Jenkins became home secretary. While in this post he encouraged the passing of private members' bills that legalized homosexuality and abortion. He also abolished theatre censorship. As a result the Daily Telegraph called him the “father of permissiveness”.

Denis Healey later argued: "In my view, Roy Jenkins's best period in office was as Home Secretary in the Cabinet of 1966; he then succeeded in stamping his liberal humanism on a department not notorious for that quality. He was not well suited to the politics of class and ideology which played so large a role in the Labour Party. His natural environment was the Edwardian age on which he wrote so well. He saw politics very much like Trollope, as the interplay of personalities seeking preferment, rather than, like me, as a conflict of principles and programmes about social and economic change."

In 1967 Jenkins became chancellor of the exchequer, the second most important post in the Cabinet. Over the next three years his main strategy was to get the balance of payments in the black. By the time of the 1970 General Election he had acquired the nickname of "Surplus Jenkins".

The Conservative Party won the 1970 election. When the new House of Commons assembled Jenkins was elected deputy leader of the Labour Party. At the 1971 Party Conference he argued strongly for Britain to join the European Community. Jenkins lost the vote by five-to-one and he upset the party when he defied a three-line whip to vote with the Conservatives on this issue.

The Labour Party won the 1974 General Election and Jenkins once again became home secretary. He was responsible for two important pieces of legislation, the Sex Discrimination Act (1975) and the Race Relations Act (1976). He also led the successful "yes" campaign in the referendum on membership of the European Economic Community. When Harold Wilson resigned in 1976 Jenkins stood for the leadership of the party. However, he came only third behind James Callaghan and Michael Foot.

In 1977 Jenkins left the House of Commons to become president of the European Commission in Brussels. In this post he began to advocate the idea of European monetary union. This was considered to be too radical at the time and the result was the introduction of the European monetary system. However, he had laid the foundations for what was later to become the single currency in 2002.

The political views of Jenkins were unpopular in the Labour Party and in 1981 he joined Shirley Williams, David Owen and William Rodgers in setting up the Social Democratic Party (SDP). Jenkins became leader of the new party and in 1982 he returned to the House of Commons as MP for Glasgow Hillhead.

At the 1983 General Election the SDP-Liberal Alliance achieved 25% of the popular vote. However, the SDP won only 6 seats. After the election Jenkins resigned as leader and was replaced by David Owen. In the 1987 General Election Jenkins lost his seat at Glasglow Hillhead. Created Lord Jenkins of Hillhead he became the leader of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords.

In retirement Roy Jenkins concentrated on writing and published several books including an autobiography, A Life At The Centre (1991) and two best-selling biographies, Gladstone (1995) and Churchill (2001).