On this day on 4th October

On this day in 1537 the first complete English-language Bible, the "Matthew Bible" is printed, with translations by William Tyndale and Miles Coverdale. It included sixty-seven woodcut illustrations. The title-page of the first printing, included a picture of King Henry VIII distributing bibles. Coverdale explains that he has "with a clear conscience purely and faithfully translated this out of five sundry interpreters". He did not mention that it was largely based on the work of Tyndale. While the Bible was being printed, Tyndale was being tried by seventeen commissioners, led by three chief accusers. At their head was the greatest heresy-hunter in Europe, Jacobus Latomus, from the new Catholic University of Louvain, a long-time opponent of Erasmus as well as of Martin Luther. Tyndale conducted his own defence. He was found guilty but he was not burnt alive, as a mark of his distinction as a scholar, on 6th October, 1536, he was strangled first, and then his body was burnt. John Foxe reports that his last words were "Lord, open the king of England's eyes!"

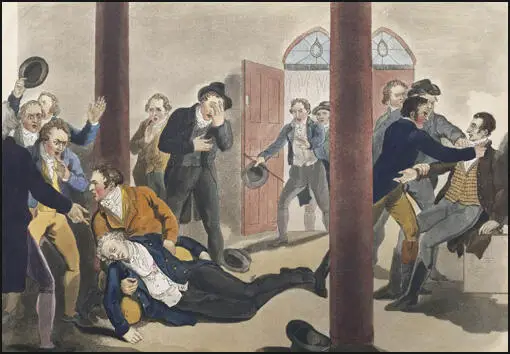

On this day in 1809 Spencer Perceval becomes Prime Minister of the United Kingdom after William Cavendish-Bentinck, Duke of Portland retires due to ill health. Perceval's period of power coincided with an economic depression and considerable industrial unrest. This resulted in his government introducing repressive methods against the Luddites. This included the Frame-Breaking Act which made the destruction of machines a capital offence. Perceval held the post until 1812 when he became the only British Prime Minister in history to be assassinated. Spencer Perceval was shot when entering the lobby of the House of Commons by John Bellingham, a failed businessman from Liverpool. Bellingham, who blamed Perceval for his financial difficulties, was later hanged for his crime.

On this day in 1890 Catherine Booth died of cancer.

Catherine Mumford, the daughter of a coachbuilder, was born in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, on 17th January 1829. When she was a child the family moved to Boston, Lincolnshire and later they lived in Brixton, London. Catherine was a devout Christian and by the age of twelve she had read the Bible eight times. She had a social conscience from an early age. On one occasion she protested to the local policeman that he had been too rough on a drunken man he had arrested and frog-marched to the local lock-up.

Catherine did not enjoy good health. At the age of fourteen she developed spinal curvature and four years later, incipient tuberculosis. It was while she was ill in bed that she began writing articles for magazines warning of the dangers of drinking alcohol. Catherine was a member of the local Band of Hope and a supporter of the national Temperance Society.

In 1852 Catherine met William Booth, a Methodist minister. William had strong views on the role of church ministers believing they should be "loosing the chains of injustice, freeing the captive and oppressed, sharing food and home, clothing the naked, and carrying out family responsibilities." Catherine shared William's commitment to social reform but disagreed with his views on women. Catherine was an avowed feminist. On one occasion she objected to William describing women as the "weaker sex". William was also opposed to the idea of women preachers. When Catherine argued with William about this he added that although he would not stop Catherine from preaching he would "not like it". Despite their disagreements about the role of women in the church, the couple married on 16th June 1855, at Stockwell New Chapel.

It was not until 1860 that Catherine Booth first started to preach. One day in Gateshead Bethesda Chapel, a strange compulsion seized her and she felt she must rise and speak. Later she recalled how an inner voice taunted her: "You will look like a fool and have nothing to say". Catherine decided that this was the Devil's voice: "That's just the point," she retorted, "I have never yet been willing to be a fool for Christ. Now I will be one."

Catherine's sermon was so impressive that William changed his mind about women's preachers. Catherine Booth soon developed a reputation as an outstanding speaker but many Christians were outraged by the idea. As Catherine pointed out at that time it was believed that a woman's place was in the home and "any respectable woman who raised her voice in public risked grave censure."

In 1864 the couple began in London's East End the Christian Mission which later developed into the Salvation Army. Catherine Booth took a leading role in these revival services and could often be seen preaching in the dockland parishes of Rotherhithe and Bermondsey. Though often imprisoned for preaching in the open air, members of the Salvation Army fought on, waging war on poverty and injustice.

The Church of England were at first extremely hostile to the Salvation Army. Lord Shaftesbury, a leading politician and evangelist, described William Booth as the "anti-christ". One of the main complaints against Booth was his "elevation of women to man's status". In the Salvation Army a woman officer enjoyed equal rights with a man. Although Booth had initially rejected the idea of women preachers, he had now completely changed his mind and wrote that "the best men in my Army are the women."

Catherine Booth began to organize what became known as Food-for-the-Million Shops where the poor could buy hot soup and a three-course dinner for sixpence. On special occasions such as Christmas Day, she would cook over 300 dinners to be distributed to the poor of London.

By 1882 a survey of London discovered that on one weeknight, there were almost 17,000 worshipping with the Salvation Army, compared to 11,000 in ordinary churches. Even, Dr. William Thornton, the Archbishop of York, had to accept that the Salvation Army was reaching people that the Church of England had failed to have any impact on.

It was while working with the poor in London that Catherine found out about what was known as "sweated labour". That is, women and children working long hours for low wages in very poor conditions. In the tenements of London, Catherine discovered red-eyed women hemming and stitching for eleven hours a day. These women were only paid 9d. a day, whereas men doing the same work in a factory were receiving over 3s. 6d. Catherine and fellow members of the Salvation Army attempted to shame employers into paying better wages. They also attempted to improve the working conditions of these women.

Catherine was particularly concerned about women making matches. Not only were these women only earning 1s. 4d. for a sixteen hour day, they were also risking their health when they dipped their match-heads in the yellow phosphorus supplied by manufacturers such as Bryant & May. A large number of these women suffered from 'Phossy Jaw' (necrosis of the bone) caused by the toxic fumes of the yellow phosphorus. The whole side of the face turned green and then black, discharging foul-smelling pus and finally death.

Women like Catherine Booth and Annie Beasant led a campaign against the use of yellow phosphorus. They pointed out that most other European countries produced matches tipped with harmless red phosphorus. Bryant & May responded that these matches were more expensive and that people would be unwilling to pay these higher prices.

Catherine Booth died of cancer on 4th October 1890. The campaigns that were started by Catherine were not abandoned. William Booth decided he would force companies to abandon the use of yellow phosphorus. In 1891 the Salvation Army opened its own match-factory in Old Ford, East London. Only using harmless red phosphorus, the workers were soon producing six million boxes a year. Whereas Bryant & May paid their workers just over twopence a gross, the Salvation Army paid their employees twice this amount.

William Booth organised conducted tours of MPs and journalists round this 'model' factory. He also took them to the homes of those "sweated workers" who were working eleven and twelve hours a day producing matches for companies like Bryant & May. The bad publicity that the company received forced the company to reconsider its actions. In 1901, Gilbert Bartholomew, managing director of Bryant & May, announced it had stopped used yellow phosphorus.

Catherine Booth and William Booth had eight children, all of whom were active in the Salvation Army. William Bramwell Booth (1856-1929) was chief of staff from 1880 and succeeded his father as general in 1912. Catherine's second son, Ballington Booth (1857-1940), was commander of the army in Australia (1883-1885) and the USA (1887-1896). One of her daughters, Evangeline Cory Booth (1865-1950) was elected General of the Salvation Army in 1934.

On this day in 1897 George Bernard Shaw saw the first production of Devil's Disciple in New York City. Shaw became a socialist after hearing a speech by Henry George on land nationalization. Shaw joined the Social Democratic Federation and its leader, H. H. Hyndman, introduced him to the works of Karl Marx. Shaw was convinced by the economic theories in Das Kapital but was aware that it would have little impact on the working class. He later wrote that although the book had been written for the working man, "Marx never got hold of him for a moment. It was the revolting sons of the bourgeois itself - Lassalle, Marx, Liebknecht, Morris, Hyndman, Bax, all like myself, crossed with squirearchy - that painted the flag red. The middle and upper classes are the revolutionary element in society; the proletariat is the conservative element." In May 1884 Shaw joined the Fabian Society and the following year, the Socialist League, an organisation that had been formed by William Morris and Eleanor Marx after a dispute with Hyndman, the leader of the SDF.

On this day in 1914 French and British fleet bombards Turkish forts at Dardanelles (a 41 mile strait between Europe and Asiatic Turkey that were overlooked by high cliffs on the Gallipoli Peninsula). It was a plan devised by Winston Churchill who was concerned about the threat that Turkey posed to the British Empire and feared an attack on Egypt. At first the plan was initially rejected by H. H. Asquith, David Lloyd George, Admiral John Fisher and Lord Kitchener. Admiral Fisher wrote to Admiral John Jellicoe, Commander of the Grand British Fleet, arguing: "I just abominate the Dardanelles operation, unless a great change is made and it is settled to be made a military operation, with 200,000 men in conjunction with the Fleet." Maurice Hankey, secretary of the Imperial War Cabinet, agreed with Fisher and circulated a copy of the Committee of Imperial Defence assessment that was against a purely naval assault on the Dardanelles.

On this day in 1936 the Battle of Cable Street took place. In an attempt to increase support for their campaign, the British Union of Fascists announced its attention of marching through the East End on 4th October 1936, wearing their Blackshirt uniforms. The Jewish People's Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism produced a petition that stated: "We the undersigned citizens of East London, view with grave concern the proposed march of the British Union of Fascists upon East London. The avowed object of the Fascist movement in Great Britain is the incitement of malice and hatred against sections of the population. It aims to further ends which seek to destroy the harmony and goodwill which has existed for centuries among the East London population, irrespective of differences in race and creed. We consider racial incitement, by a movement which employs flagrant distortions of the truth and degrading calumny and vilification, as a direct and deliberate provocation to attack. We therefore make an appeal to His Majesty's Secretary of State for Home Affairs to prohibit such matters and thus retain peaceable and amicable relations between all sections of East London's population."

Within 48 hours over 100,000 people signed the petition and it was presented to 2nd October deputation was headed by James Hall, the Labour Party M.P. for Whitechapel, Father St John Beverley Groser and Alfred M. Wall (Secretary of the London Trades Council). (62) George Lansbury, the M.P. for Bow & Bromley, also wrote to John Simon, the Home Secretary, and asked for the march to be diverted. Simon refused and told a deputation of local mayors that he would not interfere as he did not wish to infringe freedom of speech. Instead he sent a large police escort in an attempt to prevent anti-fascist protesters from disrupting the march.

The Independent Labour Party responded by issuing a leaflet calling on East London workers to take part in the counter demonstration which assembles at Aldgate at 2.p.m. As a result the anti-fascists, adopting the slogan of the Spanish Republicans defending Madrid "They Shall Not Pass" and developed a plan to block Mosley's route. One of the key organizers was Phil Piratin, a leading figure in the Stepney Tenants Defence League. Denis Nowell Pritt and other members of the Labour Party also took part in the campaign against the march.

The Jewish Chronicle told its readers not to take part in the demonstration: "Urgent Warning. It is understood that a large Blackshirt demonstration will be held in East London on Sunday afternoon. Jews are urgently warned to keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march from their meetings. Jews who, however innocently, became involved in any possible disorders will be actively helping anti-Semitism and Jew-baiting. Unless you want to help the Jew-baiters - Keep Away."

The Daily Herald reported that by "1.30 p.m.... anti-Fascists had massed in tens of thousands. They formed a solid block at the junction of Commercial Street, Whitechapel Road and Aldgate. It was through this area that Mosley would have to reach his goal, Victoria Park, Stepney and the Socialists, Jews and Communists of the East End were determined that 'Mosley should not pass!' At the time every available policeman - about 10,000 in all - was converging on Whitechapel from all parts of London. Mounted police rode into the huge throng and forced the demonstrators back into the streets. Cordons were then flung across to keep a clear space for the marchers."

Father St John Beverley Groser, of Christ Church, Watney Street, was a Christian Socialist and was one of the main organisers of the demonstration. He was hit several times by police batons and suffered a broken nose. The Church authorities were very unhappy with his involvement and his licence to preach was removed for a time. He had been previously forced to resign from the church after supporting the trade union movement during the General Strike.

By 2.00 p.m. 50,000, people had gathered to prevent the entry of the march into the East End, and something between 100,000 and 300,000 additional protesters waited on the route. Barricades were erected across Cable Street and the police endeavoured to clear a route by making repeated baton charges. One of the demonstrators said that he could see "Mosley - black-shirted himself - marching in front of about 3,000 Blackshirts and a sea of Union Jacks. It was as though he were the commander-in-chief of the army, with the Blackshirts in columns and a mass of police to protect them."

Eventually at 3.40 p.m. Sir Philip Game, the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in London, had to accept defeat and told Mosley that he had to abandon their march and the fascists were escorted out of the area. Max Levitas, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Stepney later pointed out: "It was the solidarity between the Labour Party, the Communist Party and the trade union movement that stopped Mosley's fascists, supported by the police, from marching through Cable Street." William J. Fishman said: "I was moved to tears to see bearded Jews and Irish Catholic dockers standing up to stop Mosley. I shall never forget that as long as I live, how working-class people could get together to oppose the evil of fascism."

The Manchester Guardian supported the Home Secretary's decision to allow the BUF's march as it demonstrated that the Fascists had the right to hold a procession, but correctly banned it, when it showed signs of getting out of control. The Times condemned the actions of the anti-fascists and concluded, "that this sort of hooliganism must clearly be ended, even if it involves a special and sustained effort from the police authorities." The Daily Telegraph praised the Police Commissioner Hugh Trenchard "as he was on the side of free speech, and those who assembled to resist the march threatened it."

A total of 79 anti-fascists were arrested at during the Battle of Cable Street. Several of these men received a custodial sentence. This included the 21 year-old, Charlie Goodman. One of his prison experiences highlighted the conflict between the conservative Jewish establishment and left-wing Jews: "I was visited by a Mr Prince from the Jewish Discharged Prisoners Aid Society... an arm of the Board of Deputies who called all the Jewish prisoners together." He asked them what crimes they had committed. The first five or six prisoners admitted to crimes such as robbery and he replied, "Don't worry, we'll look after you." When he asked Goodman he replied, "fighting fascism". This provoked Prince into saying: "You are the kind of Jew who gives us a bad name... It is people like you that are causing all the aggravation to the Jewish people."

According to one police report, Mick Clarke, one of the fascist leaders in London told one meeting: "It is about time the British people of the East End knew that London's pogrom is not very far away now. Mosley is coming every night of the week in future to rid East London and by God there is going to be a pogrom." As John Bew has pointed out: "That was not the end of the matter. Labour Party meetings were frequently stormed by fascists over the following months. Stench bombs would be put through a window, doors would be kicked open, and fists would fly."

On this day in 1938 all members of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War are asked leave the frontline. This followed a speech made by Juan Negrin where he announced to the United Nations the unconditional withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. This was not a great sacrifice as there were fewer than 10,000 foreigners left fighting for the Popular Front government. The International Brigades had suffered heavy casualties - 15 per cent killed and a total casualty rate of 40 per cent. At this time there were about 40,000 Italian troops in Spain. Benito Mussolini refused to follow Negrin's example and in reply promised to send Franco additional aircraft and artillery. The International Brigades left Barcelona on 29th October 1938. Dolores Ibárruri, made a farewell speech. "Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of state, the good of that same cause for which you offered your blood with limitless generosity, send some of you back to your countries and some to forced exile. You can go with pride. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of the solidarity and the universality of democracy. We will not forget you; and, when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic's victory, come back! Come back to us and here you will find a homeland." Approximately 4,900 soldiers died fighting for the Republicans (2,000 Germans, 1,000 French, 900 Americans, 500 British and 500 others).

1936. Left to right: Sid Avner, Nat Cohen, Ramona, Tom Winteringham,

George Tioli, Jack Barry and David Marshall.

On this day in 1942 General Friedrich Paulus, who had lost 40,000 soldiers since entering Stalingrad, was running out of fighting men and made a desperate plea to Hitler for reinforcements. Aware that the 6th Army was in danger of being starved into surrender, Adolf Hitler ordered Field Marshal Erich von Manstein and the 4th Panzer Army to launch a rescue attempt. Manstein managed to get within thirty miles of Stalingrad but was then brought to a halt by the Red Army. On 27th December, 1942, Manstein decided to withdraw as he was also in danger of being encircled by Soviet troops. In Stalingrad over 28,000 German soldiers had died in just over a month. With little food left General Friedrich Paulus gave the order that the 12,000 wounded men could no longer be fed. Only those who could fight would be given their rations. Erich von Manstein now gave the order for Paulus to make a mass breakout. Paulus rejected the order arguing that his men were too weak to make such a move. On 30th January, 1943, Adolf Hitler promoted to Paulus to field marshal and sent him a message reminding him that no German field marshal had ever been captured. Hitler was clearly suggesting to Paulus to commit suicide but he declined and the following day surrendered to the Red Army. The last of the Germans surrendered on 2nd February. The battle for Stalingrad was over. Over 91,000 men were captured and a further 150,000 had died during the siege. The German prisoners were forced marched to Siberia. About 45,000 died during the march to the prisoner of war camps and only about 7,000 survived the war.

On this day in 1943 Heinrich Himmler made a speech to Schutzstaffel (SS) officers at Poznan. It included the following words: "I also want to talk to you, quite frankly, on a very grave matter. Among ourselves it should be mentioned quite frankly, and we will never speak of it publicly. Just as we did not hesitate on 30 June 1934 to do the duty we were bidden and stand comrades who had lapsed up against the wall and shoot them, so we have never spoken about it and will never speak of it. It was that tact which is a matter of course and which I am glad to say, inherent in us, that made us never discuss it among ourselves, nor speak of it. It appalled everyone, and yet everyone was certain that he would do it the next time if such orders are issued and if it is necessary. I mean the evacuation of the Jews, the extermination of the Jewish race.... Most of you must know what it means when one hundred corpses are lying side by side, or five hundred, or one thousand. To have stuck it out and at the same time - apart from exceptions caused by human weakness - to have remained decent fellows, that is what has made us hard. This is a page of glory in our history which has never been written and is never to be written, for we know how difficult we should have made it for ourselves, if with the bombing raids, the burdens and the deprivations of war we still had Jews today in every town as secret saboteurs, agitators, and troublemakers. We would now probably have reached the 1916-1917 stage when the Jews were still in the German national body."

On this day in 1957 Milovan Djilas is imprisoned in Yugoslavia for spreading hostile propaganda. During the Second World War Djilas joined with his friend Josip Tito to help establish the partisan resistance fighters. Djilas was commander of the resistance forces in Montenegro and Bosnia during the war. In 1944 Tito sent Djilas to the Soviet Union where he had meetings with Joseph Stalin. In March 1945 Tito became premier of Yugoslavia. Over the next few years he created a federation of socialist republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Macedonia). Djilas was vice president in Tito's government.

Tito had several disagreements with Joseph Stalin and in 1948 he sent Djilas as head of a Yugoslav delegation to meet Stalin in Moscow. Negotiations failed and later that year Tito took Yugoslavia out of the Comintern and pursued a policy of "positive neutralism". Influenced by the ideas of Djilas, Tito attempted to create a unique form of socialism that included profit sharing workers' councils that managed industrial enterprises.

Despite these reforms Djilas remained critical of how communism was developing in Yugoslavia and wrote about these issues in Belgrade newspapers. In 1954 he was expelled from the party and lost all his government posts. In 1955 Djilas published The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System. In his book Djilas argued that communism in Eastern Europe was not an egalitarian society that it claimed to be. Instead, he argued, the party had established privileges enjoyed by a small group of party members (the New Class). Djilas was arrested in November 1956 and charged with "slandering and writing opinions hostile to the people and the state of Yugoslavia." Djilas was sentenced in October 1957 to nine years in prison.