On this day on 3rd June

On this day in 1879 Vivian Woodward was born in Kennington, Surrey. He was the seventh of eight children born to John and Anna Woodward. Vivian's father was a successful architect and a Freeman of the City of London.

The family also owned a home in Clacton-on-Sea, a town established in 1871 to cater specifically for the wealthy upper middle classes. Vivian went to the private school, Ascham College. An outstanding sportsman, he played cricket for the school First XI at the age of twelve. He was an even better footballer, but his father insisted he concentrated on cricket and tennis while at school.

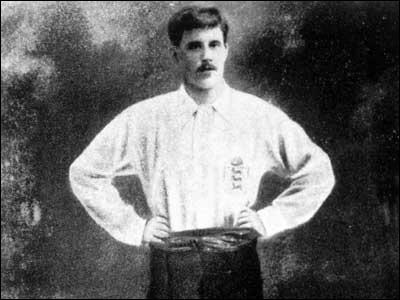

Woodward was slightly built and opponents used dubious tactics to counteract his speed and skill. However, he soon became the star of the Ascham College team. His father eventually relented and at the age of 16 he was allowed to play centre forward for Clacton Town in the North Essex League First Division. In fact, John Woodward now became vice-president of the club. The local newspaper, the Clacton Graphic, was soon reporting that "V. J. Woodward was the back-bone and centre of attraction in the team".

Vivian Woodward became an architect like his father and resisted all attempts to become a professional footballer. However, he did agree to play on amateur terms for Tottenham Hotspur in the Southern League. At the time Spurs was considered to be one of the best teams in the country having won the 1901 FA Cup Final against Sheffield United.

Woodward's work came first and on several occasions he did not play for the team for business reasons. He also missed the first few games of every season because of his commitment to the Spencer Cricket & Lawn Tennis Club. . He was one of England's best tennis players and tended to put this sport before football. When he signed for Spurs the club announced that he would play for them whenever it was "convenient for him to play."

Woodward remained an amateur throughout his football career. He came from a wealthy family and did not even claim bus or train fares or other legitimate expenses. The Tottenham & Stamford Hill Times carried an article about professionalism in football soon after Woodward signed for Tottenham Hotspur: "Football is a profession is making great strides in popularity among the masses of today. A few years back professional football was only considered good enough for the poorest class, and for a man in a fair position to enter the ranks of the pro's - well, he was a fool, at least, that was the opinion of the majority of the south."

Woodward's form for Tottenham Hotspur was so good that he won his first full international cap for England against Ireland on 14th February, 1903. He scored two goals in England's 4-0 victory. The following day the Times reported that Woodward "certainly added to the reputation he is making as a centre-forward." Another journalist described Woodward as: "The human chain of lightning, the footballer with magic in his boots."

In its next edition the Sporting Chronicle remarked: "Woodward is quite young, stands 5ft 10ins, and tips the beam at 11 stone. I should prefer him to be a little heavier, but weight will come... With a subtle craft tucked away in his toes he combines most adroit head work, and between the two he opens out the game in dazzling style. Woodward is a great initiator, the personification of unselfishness, is quick to grasp the ever-changing situation of the game, and, above all, is very cool."

The following month Woodward played for England against Wales. Woodward scored in England's 2-1 win. C. B. Fry was very impressed with Woodward's performance. He wrote: "It must be very satisfactory to the selectors to find Woodward so great a success at centre forward, especially as he is likely to improve for several years to come... It will be a surprise and a great disappointment now if he does not get his cap against Scotland."

James Catton, Britain's top football journalist at the time, thought that Woodward was a better inside-right than centre-forward: "Much was required to arouse Vivian John Woodward to resentment because his game was all art and no violence. It may be that Woodward had hard experiences in some of his matches against Scotland, while he was played in the centre, but there came a day when he was moved to inside-right, and there he was at his very best - his perfect heading and his deft passes having great effect."Woodward was selected for the Scotland game that took place on 4th April, 1903. Woodward beat Ted Doig in the Scotland goal after only 10 minutes but England lost the game 2-1. It had been a great start to his international career scoring four goals in his first three games. C. B. Fry and other commentators compared him to the great Gilbert Oswald Smith, who Woodward had replaced in the England team.

Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, thought that Woodward was a better player than Smith: "I am going to make a statement that may be considered startling, but as my opinion is honest, I am not concerned if it does not agree with the views of others. G.O. Smith and Woodward were both great players, but the Tottenham and Chelsea forward was the better. Why was he the better footballer? Woodward was the more versatile, the more consistent, and cleverer with his heading... And it should be remembered that Woodward... was faster than he looked, and that he had a neat trick of feinting, or what some call 'selling the dummy'. The most unselfish of forwards, he was a master-model of team work."

Although Woodward always played for England but was not always available for Tottenham Hotspur. In the 1906-07 season Woodward did not play his first game until the start of October. The Tottenham Herald reported: "After an indifferent beginning the Spurs... are perhaps the most respected team in the Southern League... The introduction of V. J. Woodward has had a most beneficial effect... He has pulled the forwards together, and the team has brightened up all round."

Vivian Woodward was only slightly built and he was often the target of some very rough tackling. This resulted him in missing a lot of games through injury. After a game against Fulham on 29th October, 1906, when Woodward took a terrible battering, newspapers called for referees and football authorities to do more to protect skillful players against the crude tactics of defenders.

As the journalist, Arthur Haig-Brown, pointed out in 1903: "It is a 1,000 pities that his lack of weight renders him a temptation which the occasionally unscrupulous half-back finds himself unable to resist." However, he went onto point out that this did not stop him scoring a lot of goals: "His record of goals both in League matches and in Internationals is a flattering one, for, all said and done, the most important duty of a centre forward is to find the net, and find it often."

Although he was only 5ft 10ins tall and weighed less than 11 stone, Woodward was considered the best header of the ball in football. Frederick Wall, the president of the Football Association, argued that in 50 years of watching football, only Sandy Turnbull and Dixie Dean could compare with Woodward in the air. As he pointed out: "Woodward was as dangerous near goal with his head as any man I have seen."

In 1906 the Football Association began organizing amateur internationals. The England team went on an international tour and in their first game they beat France 15-0 with Woodward scoring eight goals.

Woodward returned to the full-international side on 6th April 1907. The England team included Steve Bloomer, Bob Crompton, William Wedlock and Colin Veitch but could only draw 1-1 against Scotland.

Woodward arrived late again for the start of the 1907-08 season. On 6th September, 1907, the club reported that: "V. J. Woodward will remain faithful to cricket and tennis for a little longer, and therefore will not turn out for the Spurs just yet." That year Woodward was appointed as a director of the club. Woodward played his first game on 5th October. After a slow start he began scoring goals as Tottenham Hotspur climbed up the table. Woodward scored both goals in Spurs' 2-1 victory over Millwall. The referee was unsure if the ball had crossed the line for the first goal. Woodward declared that it did and the referee accepted this claim as he said it "was well-known that Woodward would not cheat."

Normally, Woodward refused to play over Christmas. However, that year, because Tottenham Hotspur stood a good chance of winning the title, Woodward played in the game against Northampton Town on Christmas Day. Woodward scored both goals in the 2-0 win. The Tottenham Herald argued that "Woodward's value to the Spurs seems to increase with every match. On Wednesday (25th December) he was again the chief figure in the home front line, and is adding to his reputation by scoring goals, eleven in the last four matches."

Woodward was appointed captain of the England team that played Ireland on the 5th February, 1908. He scored the second goal in England's 3-1 victory. The following month he scored a hat-trick in a 7-1 win over Wales. The next game was against Scotland. The England team included George Hilsdon, Bob Crompton, William Wedlock and Evelyn Lintott but could only draw 1-1.

The constant calls on Woodward's services in both full and amateur internationals meant that he missed a lot of Spurs' end of season matches, with the result that they won just four out of their last ten fixtures. Woodward went on tour with the England team in June 1908. This included a 11-1 victory over Austria, with Woodward scoring four of the goals.

Tottenham Hotspur was elected to the Second Division of the Football League in 1908. This time Woodward agreed to play for the team from the start of the season. In their first game against Wolverhampton Wanderers Woodward scored Spurs' first ever Football League goal after only six minutes. This 1-0 victory was followed by 19 more and at the end of the season Spurs finished in second place to Bolton Wanderers. Spurs had been promoted to football's First Division after just one year in the Football League.

The 1908 Olympic Games took place in London. Woodward was captain of the England team that beat Sweden (12-1) and Holland (4-0) to reach the final against Denmark. England won the gold medal by beating Denmark 2-0 on 24th October, 1908. Also in the team was Kenneth Hunt of Wolverhampton Wanderers and Harry Stapley of West Ham United.

In the summer of 1909 Woodward went on another tour of Europe as captain of England's amateur team. Woodward scored four goals in England's 9-0 win over Switzerland. He also contributed to the 11-0 victory over France in Paris.

On his return to England he announced that he intended to retire from top class football as he needed to concentrate on his architectural practice. During his time at Tottenham Hotspur he had scored 62 goals in 131 league and cup games.

Woodward decided to play instead for Chelmsford in the South Essex League. However, on 20th November, 1909, he changed his mind and announced he would play for Chelsea. It seems that Woodward was a good friend of Chelsea's chairman and he had been asked to help out during an injury crisis.

Woodward played his first game in the First Division of the Football League against Sheffield Wednesday on 27th November 1909. That game ended in defeat but the following week Chelsea beat Bristol City 4-1 with Woodward scoring two of the goals with headers. Despite the goals scored by Woodward, Chelsea was still relegated that season. Woodward's form was so good he was recalled to the international team and played in the 1-1 draw with Ireland.

In the 1910-11 season Chelsea finished in 3rd place in the Second Division. That year he played his final game for England, scoring two goals in the 6-1 victory over Wales. Over an eight year period he had scored 29 goals in 23 games (13 as captain). A record that stood until Tom Finney beat it in 1958. However, Finney played in 72 games for his 30 goals.

On 31st March, 1911, Woodward broke his arm in a game against Derby County. That year he played in only 19 out of 38 games. However, this was enough to help Chelsea finish 2nd in the league and promoted to the First Division.

The 1912 Olympic Games took place in Stockholm, Sweden. Woodward was once again captain of the England team that beat Hungary (7-0) and Finland (4-0) to reach the final against Denmark. Woodward won his second goal medal when England beat Denmark 4-2 on 4th July, 1912.

Chelsea again struggled in the First Division but with Woodward scoring 11 goals in 30 games, the club avoided relegation. The following season Chelsea finished in 8th place. Woodward, now 36 years old, was losing his pace and only scored four goals that season.

Woodward continued to play tennis and on two occasions, 1912 and 1913, reached the final of the Lawn Tennis Championship. He continued to captain the England amateur team playing his last game against Sweden on 12th June 1914. In 44 amateur internationals, Woodward scored an amazing 57 goals in 44 games.

On the outbreak of the First World War Woodward immediately joined the Territorial Army and applied for a commission in the British Army. On 9th February 1915 he was transferred to the 17th Service (Football) Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment as a second lieutenant. The Football Battalion had been founded on 12th December 1914 by William Joynson Hicks. Other members of this regiment included Walter Tull and Evelyn Lintott.

However, before he was sent to the Western Front, he still played a few games for Chelsea. That year Chelsea reached the FA Cup Final. The army agreed to release Woodward so that he could end his career at Wembley. Woodward declined the offer as he was unwilling to deprive Bob Thompson, who had been the team's regular centre-forward that season, of winning a medal. Chelsea was beaten 3-1 by Sheffield United in the final. During his time at Chelsea he had scored 34 goals in 116 games.

On 15th January 1916, the Football Battalion reached the front-line. During a two-week period in the trenches four members of the Football Battalion were killed and 33 were wounded. This included Woodward who was hit in the leg with a hand grenade. The injury to his right thigh was so serious that he was sent back to England to recover.

Woodward did not return to the Western Front until August 1916. The Football Battalion had taken heavy casualties during the Somme offensive in July. This included the death of England international footballer, Evelyn Lintott. The battle was still going on when Woodward arrived but the fighting was less intense. However, on 18th September a German attack involving poison gas killed 14 members of the battalion.

In December 1916 the Brigade Inter-Company Football Tournament took place. The 17th Middlesex beat 1st Kings (12-0) and 2nd South Staffs (10-0) on the way to the final against the 34th Brigade RFA. Understandably, the Football Battalion won the tournament. It is not known who played in these matches but it seems likely that Captain Woodward played a prominent part in this victory.

On 26th March 1917 Woodward was sent back to England to be trained as a physical training instructor at the Physical and Recreation Training School Headquarters at Aldershot. In early 1918 Woodward joined the First Army in France. After the Armistice Woodward because the coach of the British Army Football team. In 1919, aged 39, he captained the English Army to victory in the final of the "Inter-Theatre-of-War Championship" at Stamford Bridge. Woodward scored one of the goals in England's 3-2 victory over the French Army.

Vivian Woodward was eventually demobilized on 23rd May 1919 and returned to his new home at the Towers, Weeley Heath, near Clacton. Although now over forty, he still played the occasional game for Chelmsford and Clacton. On 4th March, 1920, Woodward played for Essex against Suffolk. Despite scoring a stunning goal, he could not prevent Suffolk winning 4-3. Woodward played his last game on 15th September 1920 when he turned out for Chelsea in a charity match for the families of soldiers.

Woodward also retired from his successful architectural practice in order to run a farm at Weeley Heath. He was especially proud that he had designed the main stand in the Antwerp Stadium. Woodward also established a diary business in Connaught Avenue, Frinton-on-Sea. Woodward kept his interest in football by serving as a director of Chelsea (1922-1930).

During the Second World War Woodward was a Air Raid Warden. In 1949 he was taken ill and entered a nursing home in Castlebar Road, Ealing. In 1953 he was visited by the journalist, Bruce Harris, who reported that Woodward was "bedridden, paralysed, infirm beyond his seventy-four years". Woodward complained that "no one who used to be with me in football has been to see me for two years".

Vivian Woodward died in the nursing home on 6th February, 1954.

On this day in 1900 English explorer Mary Kingsley died. Mary Kingsley, the daughter of George Kingsley and Mary Bailey, and the niece of Charles Kingsley, was born in Islington in 1862. Her father qualified as a doctor and worked for the Earl of Pembroke. Both men had a love of travelling and together they produced a book of their foreign journeys, South Sea Bubbles. Her mother was an invalid and Mary was expected to stay at home and look after her. Mary had little formal schooling but she did have access to her father's large library of travel books.

When her father was at home Mary loved to hear his stories about life in other countries and willingly agreed to help him with his proposed book he was writing on the customs and laws of people in Africa. Although Kingsley did not consider taking his daughter with him on his travels, she was given the task of making notes on relevant material from his large collection of books on the subject.

In 1891 Kingsley returned to England after one journey suffering from rheumatic fever. With both her parents invalids, Mary took complete control over the running of the household. Mary even subscribed to the journal, English Mechanic, so that she could carry out repairs on their dilapidated house.

George Kingsley died in February 1892. Five weeks later her mother also passed away. Freed from her family responsibilities, and with a income of £500 a year, Mary was now able to travel. Mary decided to visit Africa to collect the material needed that would enable her to finish off the book that her father had started on the culture of the people of Africa. Mary also offered to collect tropical fish for the British Museum while she was touring the continent.

Mary arrived at Sao Paulo de Luanda in Angola in August 1893. She lived with local people who taught her how to fish using nets made of pineapple fibre. After learning the necessary skills, she went off alone to search the mangrove swamps in search of rare specimens. Her adventures included a crocodile attacking her canoe and being caught in a tornado.

Kingsley returned in 1895 in order to study cannibal tribes. She travelled by canoe up the Ogowe River where she collected specimens of formerly unknown fish. Several times her canoe capsized in the river's dangerous rapids. Mary also journeyed through dense forests infested with poisonous snakes and scorpions and wading through swamps trying to avoid the attentions of crocodiles. After meeting the cannibal Fang tribes she climbed the 13,760 feet Mount Cameroon by a route unconquered by any other European.

News of Mary Kingsley's adventures reached England and when she landed at Liverpool she was greeted by journalists who wanted to interview her about her experiences. Kingsley was now famous and over the next three years she toured the country giving lectures on life in Africa. In her talks she challenged the views of the "stay at home statesmen, who think the Africans are awful savages or silly children - people who can only be dealt with on a reformatory penitentiary line."

Mary Kingsley upset the Church of England when she criticised missionaries for trying to change the people of Africa. She defended polygamy and other aspects of African life that had shocked people living in Britain. Mary argued that a "black man is no more an undeveloped white man than a rabbit is an undeveloped hare."

The Temperance Society was also angered by Kingsley's defence of the alcohol trade in Africa. The African, she argued, is "by no means the drunken idiot his so-called friends, the Protestant missionaries, are anxious, as an excuse for their failure in dealing with him, to make out."

Kingsley held conservative views on women's emancipation. When the Daily Telegraph described her as a "New Women" she wrote a letter of complaint argued that "I did not do anything without the assistance of the superior sex."

In a speech she made on women's suffrage in 1897 she argued against women being given the vote in parliamentary elections. Kingsley claimed that the country already suffered from having a poorly informed House of Commons and believed that the "addition of a mass of even less well-informed women would only make matters worse." According to Kingsley, "women are unfit for parliament and parliament is unfit for them". However, women she believed were well informed on domestic issues and fully supported women taking part in local elections.

Kingsley first book about her experiences, Travels in West Africa (1897) was an immediate best-seller. In her second book, West African Studies (1899) she described the laws and customs of the people in Africa and explained how best they could be governed. Joseph Chamberlain, the government's Colonial Secretary, wrote to Kingsley seeking her advice. However, Kingsley was such a controversial figure he asked her to keep their meetings secret.

Kingsley's descriptions of the behaviour of missionaries and traders in Africa inspired the young journalist, E. D. Morel, to carry out his own research into the problem. This resulted in a series of articles entitled The Congo Scandal (1900) that eventually had an impact on government policy.

On the outbreak of the Boer War, Kingsley volunteered to work as a nurse. When the editor of the Morning Post heard she was going, he asked her to report on the war. However, her work as a nurse in Simonstown kept her fully occupied. In a letter to a friend in England, Kingsley explained how typhoid fever was daily killing four of five of her patients. She also described fellow nurses dying of the disease and added that she thought it was unlikely that she would survive. Her prediction was unfortunately accurate and she died on 3rd June, 1900. As requested just before her death, Mary Kingsley was buried at sea.

On this day in 1937 the former King Edward VIII married Wallis Simpson at the Château de Candé in France, owned by Charles Eugene Bedaux, a man suspected of being a Nazi agent (he committed suicide after being arrested by the FBI in 1944). The new king, his younger brother, George VI, granted him the title, the Duke of Windsor. However, under pressure from the British government, the king refused to extend to the new duchess of Windsor the rank of "royal highness"

Edward's relationship with Simpson created a great deal of scandal. So also did his political views. In July 1933 Robert Vansittart, a diplomat, recounted in his diary that at a party where there was much discussion about the implications of Hitler's rise to power. "The Prince of Wales was quite pro-Hitler and said it was no business of ours to interfere in Germany's internal affrairs either re- the Jews or anyone else, and added that dictators are very popular these days and we might want one in England." In 1934 he made comments suggesting he supported the British Union of Fascists. According to a Metropolitan Police Special Branch report he had met Oswald Mosley for the first time at the home of Lady Maud Cunard in January 1935.

Paul Foot has argued: "Fascism... fitted precisely with Wallis’s own upbringing, character and disposition. She was all her life an intensely greedy woman, obsessed with her own property and how she could make more of it. She was a racist through and through: anti-semitic, except when she hoped to benefit from rich Jewish friends; and anti-black... She was offensive to her servants, and hated the class they came from."

The government was also aware that Wallis Simpson was in fact involved in other sexual relationships. This included a married car mechanic and salesman called Guy Trundle and Edward Fitzgerald, Duke of Leinster. More importantly, they had evidence that Wallis Simpson was having a relationship with Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German Ambassador to Britain. The FBI definitely believed this was the case and one report suggested that he had sent a bouquet of seventeen red roses to Princess Stephanie's flat in Bryanston Court because each bloom represented an occasion they had slept together.

Chips Channon also believed the couple were having an affair. He recorded in his diary: "Much gossip about the Prince of Wales' alleged Nazi leanings; he is alleged to have been influenced by Emerald Cunard (who is rather eprise with Herr Ribbentrop) through Wallis Simpson." MI5 were also concerned by Simpson's relationship with Ribbentrop and was now keeping her under surveillance. Paul Schwarz, a member of the German Foreign Office staff in the 1930s, claimed in his book, This Man Ribbentrop: His Life and Times (1943), that secrets from the British government dispatch boxes were being widely circulated in Berlin and it was believed that Simpson was the source. A FBI report stated: "Certain would-be state secrets were passed on to Edward, and when it was found that Ribbentrop... actually received the same information, immediately Baldwin was forced to accept that the leakage had been located."

Walter Monckton later explained: "Before October 1936 I had been on terms of close friendship with King Edward, and, though I had seldom met her save with the King, I had known Mrs Simpson for some considerable time and liked her well. I was well aware of the divorce proceedings which led to the decree nisi pronounced by Mr Justice Hawke at Ipswich in October. But I did not, before November 1936, think that marriage between the King and Mrs Simpson was contemplated. The King told me that he had often wished to tell me, but refrained for my own sake lest I should be embarrassed. It would have been difficult for me since I always and honestly assumed in my conversations with him that such an idea (which was suggested in other quarters) was out of the question. Mrs Simpson had told me in the summer that she did not want to miss her chance of being free now that she had the chance, and the King constantly said how much he resented the fact that Mrs Simpson's friendship with him brought so much publicity upon her and interfered with her prospects of securing her freedom. I was convinced that it was the King who was really the party anxious for the divorce, and I suspected that he felt some jealousy that there should be a husband in the background."