On this day on 2nd July

On this day in 1489 Thomas Cranmer was born at Aslockton, Nottinghamshire. He was admitted to Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1503. According to Diarmaid MacCulloch: "Cranmer took eight years to 1511, a surprisingly long time, to acquire the degree of BA: perhaps his acknowledged problems in absorbing information quickly, or family financial worries, delayed his progress."

Cranmer received his MA in 1515. Although not yet deacon or priest he still had to forfeit his fellowship of Jesus College when he married a woman who worked at an inn called The Dolphin. She became known as "Black Joan of the Dolphin" He became a teacher at Buckingham College but Joan died in childbirth and he returned to Cambridge University.

Thomas Cranmer took holy orders in 1520. In that year the university named him one of the preachers whom they were entitled by papal grant to license for preaching throughout the British Isles. During this period he was a loyal papalist and appeared to completely reject the ideas of Martin Luther. In fact, in 1523 he attacked him for "the arrogance of a most wicked man!"

Cranmer was a friend of Edward Lee, the Archbishop of York. In 1527 he joined him in a diplomatic mission to to the emperor Charles V in Spain. On his return he had a meeting with Henry VIII where they discussed the possible annulment of the king's marriage to Catherine of Aragon. At a meeting with Bishop Stephen Gardiner and Bishop Edward Foxe on 2nd August 1529, Cranmer suggested that Henry's marriage should not be decided by the canon lawyers in the ecclesiastical courts, but by theologians in the universities. Henry liked the idea and from then on Cranmer became one of his key political advisors. It has been argued that Cranmer was the ideal man for Henry, since he believed in royal supremacy over the Church but also dreaded the disorder that uncontrolled reform might lead to.

Henry VIII eventually sent a message to the Pope Clement VII arguing that his marriage to Catherine had been invalid as she had previously been married to his brother Arthur. Henry relied on Cardinal Thomas Wolsey to sort the situation out. During negotiations the Pope forbade Henry to contract a new marriage until a decision was reached in Rome. With the encouragement of Anne, Henry became convinced that Wolsey's loyalties lay with the Pope, not England, and in November 1529 he was dismissed from office.

Henry now took up Cranmer's suggestion. In February 1530, Cranmer and Bishop Gardiner, began discussing the matter with theologians from Cambridge University. They discovered their was considerable opposition to the idea, but "eventually succeeded in obtaining the opinion that Henry required, after they had handpicked a number of university doctors, whom they knew supported Henry's case, to decide the question for the University." This included Hugh Latimer who was a Lutheran. The University pronounced that a marriage of a man with his brother's widow was against the divine law, and that a Papal dispensation could not make it valid. They encountered even stronger opposition at Oxford University, but at the end of consultation they obtained a 27 to 22 vote that Henry's marriage to Catherine was against God's law."

In 1532 Cranmer went on a further diplomatic mission to Germany. Cranmer befriended the leading Lutheran theologian, Andreas Osiander, and at some stage during a summer of diplomacy, probably in July, married Margaret, a niece of Osiander's wife, Katharina Preu. This act reflects Cranmer willingness to reject the old church's tradition of compulsory celibacy. In October 1532 he discovered that William Warham had died and Henry VIII had appointed him as the next Archbishop of Canterbury. Cranmer reluctantly accepted the post but realised he would need to keep his marriage secret from the king. Eustace Chapuys sent a report to Emperor Charles V that he believed that Cranmer was a supporter of Martin Luther.

Henry's confidence in Cranmer was reflected by the decision to appoint him as a royal chaplain and he was attached to the household of Thomas Boleyn, the father of his mistress, Anne Boleyn. In December 1532 Henry discovered that Anne was pregnant. He realised he could not afford to wait for the Pope's permission to marry Anne. As it was important that the child should not be classed as illegitimate, arrangements were made for Henry and Anne to get married in secret. Cranmer later confirmed that the marriage ceremony took place on 25th January, 1533.

Thomas Cranmer was consecrated Archbishop of Canterbury in St Stephen's Church at Westminster on 30th March 1533. It was a necessary part of of the consecration ceremony that the Archbishop should take an oath, swearing to be obedient to Pope Clement VII and his successors and to defend the Roman Papacy against all men. This raised a problem for Henry. He wanted Cranmer's consecration ceremony to be correct in every detail, so that no one could claim that he had not been properly consecrated. This was because he intended in a few weeks time for Cranmer to state that the Pope had no authority in England.

Henry and his Archbishop of Canterbury eventually came up with a solution to the problem. Before entering the church, Cranmer made a statement in the chapter house at Westminster, in the presence of five lawyers. He declared that he did not intend to be bound by the oath of obedience to the Pope that he was about to take, "if it was against the law of God or against our illustrious King of England, or the laws of his realm of England".

On 9th April, 1533, Eustace Chapuys had an audience with Henry VIII . Chapuys said that his duty to God and the Emperor required him to protest most strongly against the measures which were being taken in Parliament against Catherine of Aragon. Henry replied that he was obeying God's law in refusing to cohabit with his brother's widow. Henry also said he needed a son to ensure the succession, Chapuys pointed out that he could not be sure that he would have children by a second marriage. Henry protested at this, and asked three times if he was not like other men and hinted that Anne was pregnant.

The following day Chapuys wrote a letter to Emperor Charles V and advised him to send an army to invade England. He argued that the intervention would succeed, because it would be welcomed not only by the English people but by most of the nobility, so that Henry would have no leaders to command his army and no horseman to serve in it. He went on to say that the Emperor did not have to fear King François, who would certainly not go to war with him for Henry's sake.

Charles V eventually ruled out the use of military force. As Jasper Ridley pointed out: "The operation would be much too hazardous, and Henry would have the help of his various allies; war with England might endanger the Emperor's realms, particularly Germany, where the Lutheran Princes would enter the war on Henry's side. They also rejected the idea of a trade embargo against England, for this could easily lead to war, and would injure the interests of the Emperor's subjects in the Netherlands."

Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn on 25th January, 1533. Elizabeth was born on 7th September. Thomas Cranmer became Elizabeth's godfather. Henry expected a son and selected the names of Edward and Henry. While Henry was furious about having another daughter, the supporters of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon were delighted and claimed that it proved God was punishing Henry for his illegal marriage to Anne. Retha M. Warnicke, the author of The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn (1989) has pointed out: "As the king's only legitimate child, Elizabeth was, until the birth of a prince, his heir and was to be treated with all the respect that a female of her rank deserved. Regardless of her child's sex, the queen's safe delivery could still be used to argue that God had blessed the marriage. Everything that was proper was done to herald the infant's arrival."

Archbishop Cranmer had to deal with the preacher, Elizabeth Barton. She had been claiming that if he married Anne Boleyn he would die within a month and that within six months the people would be struck down by a great plague. He was disturbed by her prophesies and ordered that she be kept under observation. Cranmer commented later that Henry put off his marriage to Anne because "of her visions".

In the summer of 1533 Thomas More met Elizabeth Barton. Soon afterwards he wrote to her warning about the dangers she faced if she continued to speak with "lay persons, of any such manner things as pertain to princes' affairs, or the state of the realm... with any person, high and low, of such manner things as may to the soul be profitable for you to show and for them to know".

In the summer of 1533 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer wrote to the prioress of St Sepulchre's Nunnery asking her to bring Elizabeth Barton to his manor at Otford. On 11th August she was questioned, but was released without charge. Thomas Cromwell then questioned her and, towards the end of September, Edward Bocking was arrested and his premises were searched. Father Hugh Rich was also taken into custody. In early November, following a full scale investigation, Barton was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Tudors (2012) has suggested: "It may be that she was put on the rack. In any case it was declared that she had confessed that all her visions and revelations had been impostures... It was then determined that the nun should be taken throughout the kingdom, and that she should in various places confess her fraudulence." (20) Barton secretly sent messages to her adherents that she had retracted only at the command of God, but when she was made to recant publicly, her supporters quickly began to lose faith in her.

In March 1534 Elizabeth Barton, Edward Bocking, Hugh Rich (warden of Richmond Priory), Henry Risby (warden of Greyfriars, Canterbury), Henry Gold (parson of St Mary Aldermary) and two laymen, Edward Thwaites and Thomas Gold, were indicted of high treason. They were all found guilty and sentenced to be executed on 20th April, 1534. They were "dragged through the streets from the Tower to Tyburn".

Pope Clement VII eventually made his decision. He announced that Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn was invalid. Henry reacted by declaring that the Pope no longer had authority in England. In November 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This gave Henry the title of the "Supreme head of the Church of England". A Treason Act was also passed that made it an offence to attempt by any means, including writing and speaking, to accuse the King and his heirs of heresy or tyranny. All subjects were ordered to take an oath accepting this.

Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused to take the oath and were imprisoned in the Tower of London. More was summoned before Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell at Lambeth Palace. More was happy to swear that the children of Anne Boleyn could succeed to the throne, but he could not declare on oath that all the previous Acts of Parliament had been valid. He could not deny the authority of the pope "without the jeoparding of my soul to perpetual damnation."

Henry's daughter, Mary I, also refused to take the oath as it would mean renouncing her mother, Catherine of Aragon. On hearing this news, Anne Boleyn apparently said that the "cursed bastard" should be given "a good banging". Henry told Cranmer that he had decided to send her to the Tower of London, and if she refused to take the oath, she would be prosecuted for high treason and executed. According to Ralph Morice it was Cranmer who finally persuaded Henry not to put her to death. Morice claims that when Henry at last agreed to spare Mary's life, he warned Cranmer that he would live to regret it. (25) Henry decided to put her under house arrest and did not allow her to have contact with her mother. He also sent some of her servants who were sent to prison.

Anne Boleyn was arrested and was taken to the Tower of London on 2nd May, 1536. Thomas Cromwell took this opportunity to destroy her brother, George Boleyn. He had always been close to his sister and in the circumstances it was not difficult to suggest to Henry that an incestuous relationship had existed. George was arrested on 2nd May, 1536, and taken to the Tower of London. David Loades has argued: "Both self control and a sense of proportion seem to have been completely abandoned, and for the time being Henry would believe any evil that he was told, however farfetched."

On 12th May, Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, as High Steward of England, presided over the trial of Henry Norris, Francis Weston, William Brereton and Mark Smeaton at Westminster Hall. Except for Smeaton they all pleaded not guilty to all charges. Thomas Cromwell made sure that a reliable jury was empanelled, consisting almost entirely of known enemies of the Boleyns. "These were not difficult to find, and they were all substantial men, with much to gain or lose by their behaviour in such a conspicuous theatre".

Few details survive of the proceedings. Witnesses were called and several spoke of Anne Boleyn's alleged sexual activity. One witness said that there was "never such a whore in the realm". The evidence for the prosecution was very weak, but "Cromwell managed to contrive a case based on Mark Smeaton's questionable confession, a great deal of circumstantial evidence, and some very salacious details about what Anne had allegedly got up to with her brother." At the end of the trial the jury returned a verdict of guilty, and the four men were condemned by Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley to be drawn, hanged, castrated and quartered. Eustace Chapuys claimed that Brereton was "condemned on a presumption, not by proof or valid confession, and without any witnesses."

George and Anne Boleyn were tried two days later in the Great Hall of the Tower. In Anne's case the verdict already pronounced against her accomplices made the outcome inevitable. She was charged, not only with a whole list of adulterous relationships going back to the autumn of 1533, but also with poisoning Catherine of Aragon, "afflicting Henry with actual bodily harm, and conspiring his death."

George Boleyn was charged with having sexual relations with his sister at Westminster on 5th November 1535. However, records show she was with Henry on that day in Windsor Castle. Boleyn was also accused of being the father of the deformed child born in late January or early February, 1536. This was a serious matter because in Tudor times Christians believed that a deformed child was God's way of punishing parents for committing serious sins. Henry VIII feared that people might think that the Pope Clement VII was right when he claimed that God was angry because Henry had divorced Catherine and married Anne.

Eustace Chapuys reported King Charles V that Anne Boleyn "was principally charged with... having cohabited with her brother and other accomplices; that there was a promise between her and Norris to marry after the King's death, which it thus appeared they hoped for... and that she had poisoned Catherine and intrigued to do the same to Mary... These things, she totally denied, and gave a plausible answer to each." She admitted to giving presents to Francis Weston but this was not an unusual gesture on her part. It is claimed that Thomas Cranmer told Alexander Ales that he was convinced that Anne Boleyn was innocent of all charges.

George and Anne Boleyn were both found guilty of all charges. Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, who presided over the trial left it to the King to decide whether Anne should be beheaded or burned alive. Between sentence and execution, neither admitted guilt. Anne declared herself ready to die because she had unwittingly incurred the King's displeasure, but grieved, as Eustace Chapuys reported, for the innocent men who were also to die on her account."

On 18th May, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer sat as judge at Lambeth Palace to try Henry's petition for divorce against Anne Boleyn. Cranmer had the problem of finding a reason for reversing his decision of three years earlier that Henry's marriage to Anne had been valid. There were two possible grounds for invalidating it: the existence of a precontract between Anne and Henry Percy, and the fact that Anne's sister, Mary Boleyn, had been Henry's mistress. Percy denied that there had been a pre-contract. Henry VIII did not want the public to know he had an affair with Mary, so Cranmer tried the case in private and granted the divorce without publicly announcing the reason for his decision. According to the imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, the grounds for the annulment included the king's previous relationship with Mary Boleyn. However, this information has never been confirmed.

On this day in 1644 the Battle of Marston Moor. In 1644 the Scots joined forces with Parliamentary forces to lay siege to the Royalist held city of York. In June 1644 Prince Rupert and his Cavaliers set out to rescue the Earl of Newcastle and his forces. On 2nd July the Royalists confronted the Parliamentarians at Marston Moor.

Edward Montagu and Thomas Fairfax, the leaders of the Parliamentary forces, decided to withdraw from Marston Moor towards Tadcaster in order to cut off any attempt by the Earl of Newcastle to escape. Prince Rupert decided to attack the retreating troops. This resulted in the Parliamentary army being ordered back to Marston Moor.

That afternoon Oliver Cromwell and his forces charged John Byron and his cavalry. His men, instead of pursuing Byron's cavalry, regrouped and returned to protect the infantry that had now come under attack from George Goring and his cavalry.

The Earl of Newcastle and his Whitecoat regiment made a heroic last stand and resisted repeated charges by the Parliamentary army until no more than 30 were left alive.

The battle lasted two hours. Over 3,000 Royalists were killed and around 4,500 were taken prisoner. The Parliamentary forces lost only 300 men. The city of York surrendered two weeks after the battle, ending Royalist power in the north of England. Prince Rupert rallied the survivors and retreated to Chester where he attempted to build a new Royalist army.

On this day in 1698 Thomas Savery patents the first steam engine. Thomas Savery, one of two sons of Richard Savery, was born at Modbury, Devon, in about 1650. He became a military engineer, and spent his spare time on mechanical experiments, and in 1696 he patented a machine to grind and polish plate glass.

One of the major problems of mining for coal, iron, lead and tin in the 17th and 18th centuries was flooding. Miners used several different methods to solve this problem. These included pumps worked by windmills and teams of men and animals carrying endless buckets of water.

Denis Papin, a French mathematician, invented the steam digester, a type of pressure cooker with a safety valve. Savery used Papin's idea of using a cylinder and a piston to design a pumping engine which incorporated two different ways of utilizing steam to generate power. Steam was pumped into a cylinder and then cooled so that a vacuum was formed and atmospheric pressure drew water up.

On 25th July 1698 Thomas Savery obtained a patent for fourteen years. The patent contained no description of the machine, but in June 1699 it was shown to members of the Royal Society. In 1702 he published a book about the invention entitled The Miner's Friend.

Savery established a workshop at Salisbury Court, London. At this workshop, mine and colliery owners could see the engine demonstrated before purchase. However, the engine could not raise water from very deep mines. Another disadvantage was its tendency to cause explosions.

According to his biographer, Christopher F. Lindsey: "It is doubtful that any machines were actually sold for use in mines, although at least two were later installed for water-supply purposes in London, namely at Campden House, Kensington, and at the York Buildings waterworks in Villiers Street. The engine was satisfactory for raising water short distances, but the intense heat required to lift water from greater depths, as in mines, tended to melt the soldered joints of the machine, which lacked proper safety features and used energy inefficiently."

Thomas Newcomen, an inventor from Dartmouth worked on this problem and he eventually came up with the idea of a machine that would rely on atmospheric air pressure to work the pumps, a system which would be safe, if rather slow. The "steam entered a cylinder and raised a piston; a jet of water cooled the cylinder, and the steam condensed, causing the piston to fall, and thereby lift water."

As Jenny Uglow has pointed out: "Newcomen's engines exploited basic atmospheric pressure, building on the way had been found to rush into a vacuum. A vacuum could be created by sucking air out of a closed vessel with a pump, but it could also be created by using steam."

Savery continued to work on the development of other machines. In 1706 he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and also patented a double hand-bellows, which could melt any metal in an ordinary wood or coal fire. He also worked on "a new sort of mill to perform all sorts of mill-work on vessells floating on the water", but no patent seems to have been granted.

Thomas Savery died at his home in Marsham Street, Westminster, on 15th May 1715.

On this day in 1842 Susanna Inge publishes an article on women's rights in The Northern Star: "As civilisation advances man becomes more inclined to place woman on an equality with himself, and though excluded from everything connected with public life, her condition is considerably improved... Assist those men who will, nay, who do, place women in on equality with themselves in gaining their rights, and yours will be gained also."

On this day in 1850 Robert Peel died. Robert Peel was born in Bury, Lancashire, on 5th February, 1788. His father, Sir Robert Peel (1750-1830), was a wealthy cotton manufacturer and member of parliament for Tamworth. Robert was trained as a child to become a future politician. Every Sunday evening he had to repeat the two church sermons that he had heard that day.

Robert Peel was educated at Harrow School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he won a double first in classics and mathematics. In 1809 Sir Robert Peel rewarded his son academic success by buying him the parliamentary seat of Cashel in County Tipperary (exchanged for Chippenham in 1812).

Robert Peel entered the House of Commons in April 1809, at the age of twenty-one. Like his father, Robert Peel supported the Duke of Portland's Tory government. He made an immediate impact and Charles Abbott, the Speaker of the Commons, described Peel's first contribution to a debate as the "the best first speech since that of William Pitt."

After only a year in the House of Commons the Duke of Portland offered him the post of under-secretary of war and the colonies. Working under Lord Liverpool, Peel helped to direct the military operations against the French.

When Lord Liverpool became prime minister in May 1812, Peel was appointed as chief secretary for Ireland. In his new post Peel attempted to bring an end to corruption in Irish government. He tried to stop the practice of selling public offices and the dismissal of civil servants for their political views. At first Peel also attempted to end those aspects of government that gave preference to Protestants over Catholics. However, Robert Peel was not successful in carrying out this policy and eventually he became seen as one of the leading opponents to Catholic Emancipation.

In 1814 he decided to suppress the Catholic Board, an organisation started by Daniel O'Connell. This was the start of a long conflict between the two men. In 1815 Peel challenged O'Connell to a duel. Peel travelled to Ostend but O'Connell was arrested on the way to fight the duel.

In 1817 Robert Peel decided to retire from his post in Ireland. This upset the Irish Protestants in the House of Commons and fifty-seven of them signed a petition urging him not to leave a post that they believed he had "administered with masterly ability". Oxford University acknowledged Peel's "services to Protestantism" by inviting him to become its member of the House of Commons.

In 1822 Peel rejoined Lord Liverpool's government when he accepted the post of Home Secretary. Over the next five years Peel was responsible for large-scale reform in the legal system. This involved repealing over 250 old statutes.

Lord Liverpool was struck down by paralysis in February 1827 and was replaced by George Canning as prime minister. Canning was an advocate of Catholic Emancipation and as Peel was strongly opposed to this, he felt he could not serve under the new prime minister and resigned from office. After the death of Canning he returned to government as Home Secretary in the government led by the Duke of Wellington.

On 26th July, 1828, Lord Anglesey, wrote to Peel arguing that Ireland was on the verge of rebellion and asked him to use his influence to gain concessions for the Catholics. Although Peel had opposed Catholic Emancipation for twenty years, Lord Anglesey's letter encouraged him to reconsider his position. Peel now wrote to Wellington saying that "though emancipation was a great danger, civil strife was a greater danger". He also added that as William Pitt had rightly said: "to maintain a consistent attitude amid changed circumstances is to be a slave of the most idle vanity".

Although the Duke of Wellington agreed with Peel, King George III was violently opposed to Catholic Emancipation. When Wellington's government threatened to resign the king reluctantly agreed to a change in the law. When Peel introduced the Catholic Emancipation Act on 5th March, 1829, he told the House of Commons that the credit for the measure belonged to his long-time opponents, Charles Fox and George Canning.

For a long time politicians had been concerned about the problems of law and order in London. In 1829 Robert Peel decided to reorganize the way London was policed. As a result of this reform, the new metropolitan police force became known as "Peelers" or "Bobbies".

In November 1830, Wellington's government was replaced by a new administration headed by Earl Grey. For the first time in over twenty years in the House of Commons, Peel was now a member of the opposition. Peel was totally against Grey's proposals for parliamentary reform. Between 12th and 27th July 1831, Peel made forty-eight speeches in the Commons against this measure. One of Peel's main arguments was that the system of rotten boroughs had enabled distinguished men to enter parliament.

After the passing of the 1832 Reform Act the Tories were heavily defeated in the general election that followed. Although victorious at Tamworth, Peel, now leader of the Tories, only had just over hundred MPs he could rely on to support him against Earl Grey's government.

In November 1834 King William IV dismissed the Whig government and appointed Robert Peel as his new prime minister. Peel immediately called a general election and during the campaign issued what became known as the Tamworth Manifesto. In his election address to his constituents in Tamworth, Peel pledged his acceptance of the 1832 Reform Act and argued for a policy of moderate reforms while preserving Britain's important traditions. The Tamworth Manifesto marked the shift from the old, repressive Toryism to a new, more enlightened Conservatism.

The general election gave Peel more supporters although there were still more Whigs than Tories in the House of Commons. Despite this, the king invited Peel to form a new administration. With the support of the Whigs, Peel's government was able to pass the Dissenters' Marriage Bill and the English Tithe Bill. However, Peel was constantly being outvoted in the House of Commons and on 8th April 1835 he resigned from office.

In August 1841 Robert Peel was once again invited to form a Conservative administration. Over the last few years Britain had been spending more than it was earning. Peel decided the government had to increase revenue. On 11th March, 1842, he announced the introduction of income-tax at sevenpence in the pound. He added, that he hoped that this was enable the government to reduce duties on imported goods.

In 1843 Peel once more had problems with Daniel O'Connell, who was leading the campaign against the Act of Union. O'Connell announced a large meeting to be held at Clontarf. The British government pronounced it illegal and when O'Connell continued to go ahead with his planned Clontarf meeting he was arrested and imprisoned for conspiracy. Peel attempted to overcome the religious conflict in Ireland by setting up the Devon Commission to inquire into the "state of the law and practice in respect to the occupation of land in Ireland." He also increased the grant to Maynooth College for the education of the Irish priesthood, from £9,000 to £26,000 a year.

However, Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland was severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn. Although the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, the policy split the Conservative Party and Peel was forced to resign.

Robert Peel continued to attend the House of Commons and gave considerable support to Lord John Russell and his administration in 1846-47. On 28th June 1850 he gave an important speech on Greece and the foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. The following day, while riding up Constitution Hill, he was thrown from his horse. Peel was badly hurt and on 2nd July, 1850, he died from his injuries.

On this day in 1903 Alec Douglas-Home, the son of the 13th Earl of Home, was born in London on 2nd July, 1903. Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, he joined the Conservative Party and was elected to the House of Commons in the 1931 General Election.

Douglas-Home served as parliamentary private secretary to Neville Chamberlain and was involved in the negotiations with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini between 1937 and 1939.

During the Second World War Douglas-Home spent time in hospital as a result of a spinal operation. He lost his seat in the 1945 General Election but returned to the House of Commons in 1950. The following year, on the death of his father, he became the 14th Earl of Home.

In 1951 Winston Churchill appointed him as Minister of State at the Scottish Office. He held the post for six years before Anthony Eden made him Commonwealth Relations Secretary (1955-1960), Lord President of the Council (1957-1960) and Foreign Secretary (1960-63). During this period he also served as leader of the House of Lords.

When Harold Macmillan resigned in October, 1963, the Earl of Home became prime minister. He immediately resigned his peerage and won a by-election at Kinross and Western Perthshire. A year later the Conservative Party was defeated at the 1964 General Election and Harold Wilson became the new prime minister.

Edward Heath replaced Douglas Home as leader of the Conservative Party in July 1965. After the 1974 General Election Douglas-Home served as Foreign Secretary in Heath's government.

In 1974 he was granted the title Baron Home of the Hirsel of Coldstream. His autobiography, The Way the Wind Blows, was published in 1976. Other books included Border Reflections (1979) and Letters to a Grandson (1983).

Alec Douglas Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel of Coldstream, died in Berwickshire, Scotland, on 9th October, 1995.

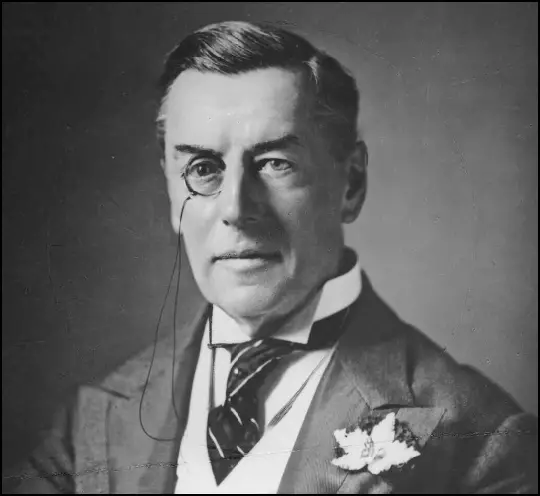

On this day in 1914 Joseph Chamberlain, the son of a shopkeeper, was born in London 1836. After being educated at University College School he became a successful businessman in Birmingham. A member of the Liberal Party he became involved in local politics and in 1868 was elected as a town councillor. Chamberlain became mayor in 1873 and for the next three years introduced a series of social reforms. The council's acquisition of land and public utilities and the pioneering slum-clearance schemes, made Chamberlain a national political figure.

Chamberlain was extremely popular in Birmingham, and was elected unopposed in a parliamentary election held in 1876. Chamberlain soon made his mark in the House of Commons and after the 1880 General Election, William Gladstone appointed Chamberlain as President of the Board of Trade.

Beatrice Webb fell in love with Chamberlain during this period: "In 1882 came the catastrophe of my life. At a London dinner-party I met Joseph Chamberlain. I was ripe for love, revelling in newly acquired health and freedom, my intelligence wide awake, my heart unclaimed. He had energy and personal magnetism. But my intellect not only remained free but positively hostile to his influence." She described a speech he made two years later: "As he rose slowly and stood silently before his people, his whole face and form seemed transformed. The crowd became wild with enthusiasm. At the first sound of his voice they became as one man. Into the tones of his voice he threw the warmth and feeling which were lacking in his words, and every thought, every feeling, the slightest intonation or irony and contempt was reflected in the face of the crowd. It might have been a woman listening to the words of her lover."

In 1885 General Election Chamberlain was seen as the leader of the Radicals with his calls for land reform, housing reform and higher taxes on the rich. However, he was also a strong supporter of Imperialism, and resigned from Gladstone's cabinet over the issue of Irish Home Rule. This action helped to bring down the Liberal government. Chamberlain now became leader of the Liberal Unionists and in 1886 he formed an alliance with the Conservative Party. As a result, Marquess of Salisbury, gave him the post of Colonial Secretary in his government. Chamberlain was therefore primarily responsible for British policy during the Boer War.

In September 1903, Joseph Chamberlain resigned from office so that he would be free to advocate his scheme of tariff reform. Chamberlain wanted to transform the British Empire into a united trading block. According to Chamberlain, preferential treatment should be given to colonial imports and British companies producing goods for the home market should be given protection from cheap foreign goods. The issue split the Conservative Party and in the 1906 General Election the Liberal Party, who supported free trade, had a landslide victory.

Chamberlain was struck down by a stroke in 1906 and took no further part in politics. Joseph Chamberlain, whose son Neville Chamberlain also became a leading figure in politics, died in 1914.

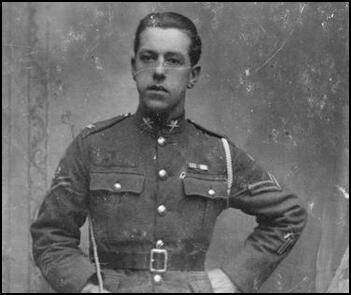

On this day in 1916 George Coppard, a machine-gunner, writes about the Battle of the Somme.

The next morning we gunners surveyed the dreadful scene in front of our trench. There was a pair of binoculars in the kit, and, under the brazen light of a hot mid-summer's day, everything revealed itself stark and clear. The terrain was rather like the Sussex downland, with gentle swelling hills, folds and valleys, making it difficult at first to pinpoint all the enemy trenches as they curled and twisted on the slopes.

It eventually became clear that the German line followed points of eminence, always giving a commanding view of No Man's Land. Immediately in front, and spreading left and right until hidden from view, was clear evidence that the attack had been brutally repulsed. Hundreds of dead, many of the 37th Brigade, were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high-water mark. Quite as many died on the enemy wire as on the ground, like fish caught in the net. They hung there in grotesque postures. Some looked as though they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall. From the way the dead were equally spread out, whether on the wire or lying in front of it, it was clear that there were no gaps in the wire at the time of the attack.

Concentrated machine gun fire from sufficient guns to command every inch of the wire, had done its terrible work. The Germans must have been reinforcing the wire for months. It was so dense that daylight could barely be seen through it. Through the glasses it looked a black mass. The German faith in massed wire had paid off.

How did our planners imagine that Tommies, having survived all other hazards - and there were plenty in crossing No Man's Land - would get through the German wire? Had they studied the black density of it through their powerful binoculars? Who told them that artillery fire would pound such wire to pieces, making it possible to get through? Any Tommy could have told them that shell fire lifts wire up and drops it down, often in a worse tangle than before.

On this day in 1925 Medgar Evers was born in Decatur, Mississippi. He served in the United States Army during the Second World War and after he returned in 1946 he found employment selling insurance.

Evers joined the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and helped organize chapters all over Mississippi. In 1954 the NAACP employed Evers as its full-time state field secretary. This main involved Evers in monitoring, collecting and publicizing data concerning civil rights violations.

Although the national leadership of the NAACP opposed mass direct action, Evers also organized and participated in sit-in protests against segregation in Mississippi. As a result of this Evers suffered several beatings and spells in prison.

Despite several warnings from local white racist groups, Evers continued to organize protests against Jim Crow laws in Mississippi. On 11th June 1963 Lena Horne arranged to speak on the same platform as Medgar Evers. That night he was murdered in the driveway of his home. Horne said: "Nobody black or white who really believes in democracy can stand aside now; everybody's got to stand up and be counted."

Byron de La Beckworth, a white segregationist, was charged with the crime but the case ended in two hung juries but was convicted in a third trial held in 1994.

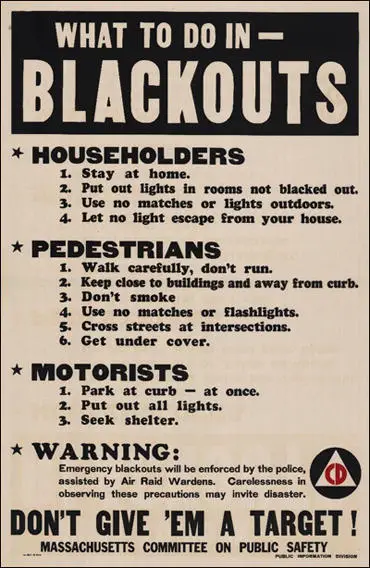

On this day in 1939 British government published circular on Lighting Restrictions. "All windows, skylights, glazed doors or other openings which would show a light, will have to be screened in wartime with dark blinds or brown paper on the glass so that no light is visible from outside. You should now obtain any materials you may need for this purpose. Instructions will be issued about the dimming of lights on vehicles. No street lighting is allowed."

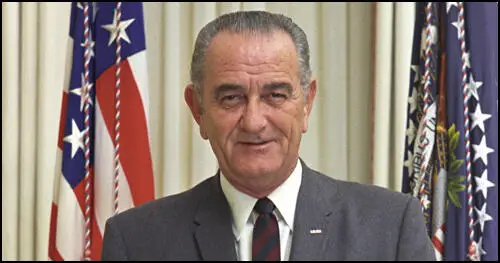

On this day in 1964 President Lyndon Baines Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In the 1960 presidential election campaign John F. Kennedy argued for a new Civil Rights Act. After the election it was discovered that over 70 per cent of the African American vote went to Kennedy. However, during the first two years of his presidency, Kennedy failed to put forward his promised legislation.

The Civil Rights bill was brought before Congress in 1963 and in a speech on television on 11th June, Kennedy pointed out that: "The Negro baby born in America today, regardless of the section of the nation in which he is born, has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one third as much chance of completing college; one third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed; about one-seventh as much chance of earning $10,000 a year; a life expectancy which is seven years shorter; and the prospects of earning only half as much."

Kennedy's Civil Rights bill was still being debated by Congress when he was assassinated in November, 1963. The new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had a poor record on civil rights issues, took up the cause. His main opponent was his long-time friend and mentor, Richard B. Russell, who told the Senate: "We will resist to the bitter end any measure or any movement which would have a tendency to bring about social equality and intermingling and amalgamation of the races in our (Southern) states." Russell organized 18 Southern Democratic senators in filibustering this bill. as I speak tonight."

However, on the 15th June, 1964, Richard B. Russell privately told Mike Mansfield and Hubert Humphrey, the two leading supporters of the Civil Rights Act, that he would bring an end to the filibuster that was blocking the vote on the bill. This resulted in a vote being taken and it was passed by 73 votes to 27.

The 1964 Civil Rights Act made racial discrimination in public places, such as theaters, restaurants and hotels, illegal. It also required employers to provide equal employment opportunities. Projects involving federal funds could now be cut off if there was evidence of discriminated based on colour, race or national origin.

The Civil Rights Act also attempted to deal with the problem of African Americans being denied the vote in the Deep South. The legislation stated that uniform standards must prevail for establishing the right to vote. Schooling to sixth grade constituted legal proof of literacy and the attorney general was given power to initiate legal action in any area where he found a pattern of resistance to the law.