On this day on 2nd December

On the day in a letter to his wife, John Irving raises doubts about the morality of the slave trade. "We have been in Tobago since the 25th November and have not yet disposed of any of our very disagreeable cargo... I'm nearly wearied of this unnatural accursed trade, and think... when convenience suits of adopting some other mode of life, although I'm fully sensible and aware of the difficulties attending any new undertaking, yet I will at least look around me."

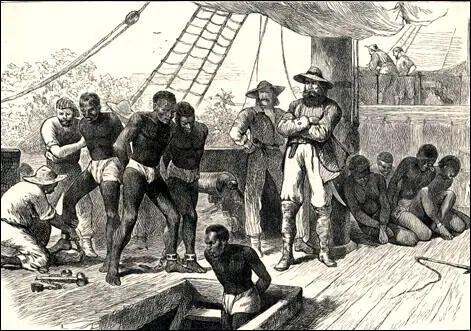

In January 1782 Irving was employed as a surgeon on the slave-ship, Prosperity. The ship based in Liverpool was captained by James Murphy and owned by John Dawson, who according to David Eltis, the author of The Volume and Structure of the Transatlantic Slave Trade (2001) was "possibly the world's leading slave trader". It has been claimed that "during his career he was involved in a number of voyages accounting for the delivery of some 3,000 slaves to the Americas". In his first trip he traded for slaves at Bight of Bonny. on the coast of West Africa.

Irving travelled to Jamaica under William Wilson on the slave-ship, Vulture in November 1782. It has been argued by Suzanne Schwarz: "Assuming that Irving was paid £4 wages a month, together with the value of two privilege slaves and one shilling head money for each of the 592 slaves delivered alive to the West Indies, it is likely that Irving earned approximately £140 from this voyage. This is consistent with the average voyage earnings of slave-ship surgeons in the late eighteenth century, which were typically between £100 and £150."

After his marriage to Mary Tunstall in Liverpool on 2nd July 1785, Irving was then recruited by Quayle Fargher, the captain of Jane. In May 1786 he sailed to Tobago. He wrote to his wife that "our black cattle are intolerably noisy and I'm almost melted in the midst of five or six hundred of them." David Richardson has argued: "Irving's insensitvity suggests that, even at a time when moral outrage in Britain at the enslavement of Africans was spreading, participation in the slave trade was still capable of promoting racism and blinding otherwise apparently quite caring individuals to the appalling suffering that they were helping to inflict on others."

The following year he served under William Sherwood on the Princess Royal, a ship that was capable of carrying up to 1,000 slaves and was the largest slave-ship owned by John Dawson and his partner, Peter Baker. His ship took over 800 slaves from Africa to Havana. In a letter to his wife in December, 1786 he wrote: "We have been in Tobago since the 25th November and have not yet disposed of any of our very disagreeable cargo... I'm nearly wearied of this unnatural accursed trade, and think... when convenience suits of adopting some other mode of life, although I'm fully sensible and aware of the difficulties attending any new undertaking, yet I will at least look around me."

In 1789 at the age of only twenty-nine, Irving was appointed as captain of the recently built, Anna. His improved financial situation enabled him to move to Pownall Square. Under the terms of the Dolben Act the ship was allowed to carry eighty slaves. He therefore only had a crew of eight men. This included John Clegg, Matthew Dawson, and three black men, Silvin Buckle, James Drachen and Jack Peters.

On 3rd May, 1789, Irving left Liverpool for Africa. On 27th May, the ship got into trouble off the Atlantic coast of Morocco. Irving later recalled that his attempts to alter the ship's course and "bring her to the wind" failed and the Anna was over-whelmed by the waves which "fell on board so heavily, and followed one another so quickly, that she soon lost head way, and struck in the hollow of the sea so very hard, that the rudder went away in a few seconds". Within ten minutes the ship filled with water and was pushed into the rocks. Irving and his crew were forced to abandon ship, and luckily they managed to safely get to the shore.

Irving and his crew were captured the following day by local Arabs and sold into slavery. Irving wrote to his wife, "all our hopes and prospects are vanished". Irving sent a letter to John Hutchinson, the British vice-counsul at Mogador (modern-day Essaouira), on the 24th June, 1789: "I hope you can feel for us, first suffering shipwreck, then seized on by a party of Arabs with outstretched arms and knives ready to stab us, next stripped to the skin, suffering a thousands deaths daily, insulted, spit upon, exposed to the sun and forced to travel through parched deserts." He pleaded with Hutchinson to "rescue us speedily from the most intolerable slavery".

Hutchinson successfully negotiated his release and after arriving in Marrakesh in January 1790 Irving informed his wife: "I have now the pleasure to tell you that after many difficulties and inconceivable hardships every one of us are got safe here in perfect health, and are under the care of our humane vice-consul, Mr. Hutchinson, who supplies us with clothes and the necessaries of life."

On his arrival in Liverpool he was reunited with his wife and his son, James, who had been born on 4th December 1789. However, it was not long before Irving was given the command of The Ellen, another ship owned by John Dawson. His crew of twenty-seven included Thomas Patton, Joseph Winters and James Bailey.

Irving wrote to his parents on 2nd January 1791: "We have been very busy loading the vessel.... We are bound for Annamaboe in the Gold Coast, discharge what goods we have for that price and set sail from it again within 48 hours after we arrived. Then we are to call at Lagos, Accra and other parts whose name I have forget. We are then to go down as far as Benin River and stay a day or two and then go back to Anomabo from which place we are to sail for the West Indies." The arrived at Annamaboe on 5th April 1791, before moving onto Lagos and Accra. While on the Gold Coast Irving purchased 341 Africans, eighty-eight of whom were transferred to other ships.

On 16th September 1791 The Ellen, with 253 slaves, sailed for Trinidad. During the journey, forty-six slaves died. James Irving died of an unspecified illness on 24th December 1791. He was the sixth and final member of the crew to die on the voyage.

On the day in 1816 followers of Thomas Spence, who died in 1814, known as the Society of Spencean Philanthropists organised a mass meeting at Spa Fields, Islington. The speakers at the meeting included Henry 'Orator' Hunt. The magistrates decided to disperse the meeting and while John Stafford and eighty police officers were doing this, one of the men, Joseph Rhodes was stabbed. The four leaders of the Spenceans, James Watson, Arthur Thistlewood, Thomas Preston and John Hopper were arrested and charged with high treason.

James Watson was the first to be tried. However, the main prosecution witness was the government spy, John Castle. The defence council was able to show that Castle had a criminal record and that his testimony was unreliable. The jury concluded that Castle was an agent provocateur (a person employed to incite suspected people to some open action that will make them liable to punishment) and refused to convict Watson. As the case against Watson had failed, it was decided to release the other three men who were due to be tried for the same offence.

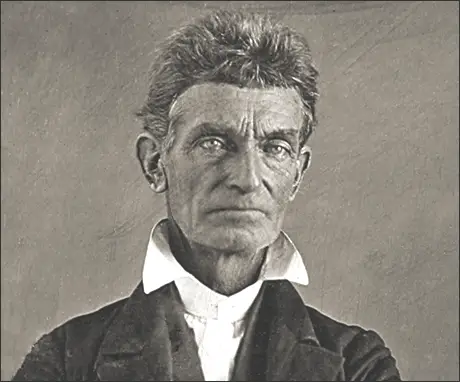

On this day in 1859 John Brown was hanged. A strong opponent of slavery, led a party of 21 men in a successful attack on the federal armory at Harper's Ferry. Brown hoped that his action would encourage slaves to join his rebellion, enabling him to form an emancipation army. Two days later the armory was stormed by Robert E. Lee and a company of marines. Brown and six men barricaded themselves in an engine-house, and continued to fight until Brown was seriously wounded and two of his sons had been killed. The song, John Brown's Body, commemorating the Harper's Ferry raid, was a highly popular marching song with Republican soldiers during the American Civil War.

On this day in 1891, Otto Dix, the eldest son of Franz Dix (1862-1942), an iron foundry worker, and Louise Amann (1864-1953), a seamstress, was born in Unternhaus, Germany. He spent a lot of time with his cousin, Fritz Amann, who was attempting to make a living as an artist.

After attending elementary school he worked locally. In 1906 he started an apprenticeship with painter Carl Senff, and began painting his first landscapes. In 1910 he became a student at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. To help fund his education, he accepted commissions and painted portraits of local people.

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Dix volunteered for the German Army and was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden. He later recalled why he joined the army: "I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I'm therefore not a pacifist at all - or am I? - perhaps I was an inquisitive person. I had to see all that for myself. I'm such a realist, you know, that I have to see everything with my own eyes in order to confirm that it's like that. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths for life for myself; it's for that reason that I went to war, and for that reason I volunteered."

In the autumn of 1915 Dix was sent to the Western Front where he served as a non-commissioned officer with a machine-gun unit. He was at the Somme during the major allied offensive during the summer of 1916. Dix was wounded several times during the war. On one occasion he nearly died when a shrapnel splinter hit him in the neck. His experiences on the front line had a dramatic impact on his art: "War is so bestial: hunger, lice, mud, those insane noises... I had the feeling, on looking at the pictures from my early years, that I had completely missed one side of reality so far, namely the ugly aspect."

In November 1917 his unit was transferred to the Eastern Front and after Russia negotiated a peace with Germany, Dix returned to France where he took part in the German Spring Offensive. In August of that year he was wounded in the neck. By the end of the war in 1918, Dix had won the Iron Cross (second class) and reached the rank of vice-sergeant-major. He was discharged from service on 22nd December 1918.

After the war Otto Dix developed left-wing views and his paintings and drawings became increasingly political. Like other German artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz, Dix became what they called "revolutionary pacifists". As Jonathan Jones has pointed out: "It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist? To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany's young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it."

Otto Dix told Maria Wetzel: "As a young man you don't notice at all that you were, after all, badly affected. For years afterwards, at least ten years, I kept getting these dreams, in which I had to crawl through ruined houses, along passages I could hardly get through. Not that painting would have been a release. The reason for doing it is the desire to create. I've got to do it! I've seen that, I can still remember it, I've got to paint it."

It has been argued by Uwe M. Schneede that Otto Dix was one of the founders of modern Verism (the artistic preference of contemporary everyday subject matter instead of the heroic or legendary in art): "From the garish over-emphasised effects of his Dadaist beginnings he came via the study of the art of previous centuries - especially of old German masters and their technique - to his ponderously constructed pictures, precise in every detail, in which the object is kept balanced between an almost aggressive here-and-now and a removal from reality."

One of his most powerful paintings was The Skat Players (1920). Influenced by the work of John Heartfield, it shows "card-playing cripples... a nightmarish vision of people so mutilated that the scarred remains are scarcely human. Arms, legs, jaws, ears and noses shot away, these men function only as a series of spare parts cobbled together, and their construction is paralleled in the way the picture has been made: it is an elaborate collage, the painted parts combined with glued-on playing-cards, newspapers and bits of wood."

In 1920 George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann organised the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in the Berlin gallery owned by Otto Burchard. It was a comprehensive manifestation of Dada (a movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works). Among the 174 works in the exhibition were pictures by Dix, Grosz, Heartfield, Hausmann, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch and Rudolf Schlichter. "The text on the panels accompanying each exhibit was partly Dadaist-polemical, partly political."

Dix was angry about the way that the wounded and crippled ex-soldiers were treated in Germany. This was reflected in paintings such as War Cripples (1920), Butcher's Shop (1920) and War Wounded (1922). In October, 1923 Dix's large painting, The Trench, was purchased by the Wallraf-Richartz Museum. The museum's director, Hans F. Secker, assured him that it had been acquired "not without blood and sweat". He added that when the new collection was to be opened to the public in December "your painting will most likely be the greatest sensation."

Walter Schmits, writing in The Kölnische Zeitung, commented: "In the cold, sallow, ghostly light of dawn…a trench appears into which a devastating bombardment has just descended. A poisonous sulphur yellow pool glistens in the depths like a smirk from hell. Otherwise the trench is filled up with hideously mutilated bodies and human fragments. From open skulls brains gush like thick red groats; torn-up limbs, intestines, shreds of uniforms, artillery shells form a vile heap... Half-decayed remains of the fallen, which were probably buried in the walls of the trench out of necessity and were exposed by the exploding shells, mix with the fresh, blood covered corpses. One soldier has been hurled out of the trench and lies above it, impaled on stakes."

When the painting was exhibited in 1924 its depiction of decomposed corpses in a German trench created such a public outcry that the museum's director hid the painting behind a curtain. The local newspaper demanded that the painting should be returned to the artist. Whereas a journalist claimed that the painting had received so much publicity that it had increased the number of people who had seen it. Another critic described it as "perhaps the most powerful as well as well as the most anti-war statements in modern art". In 1925 the then-mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, cancelled the purchase of the painting and forced Secker to resign.

On this day in 1909 the inaugural meeting of the Church League for Women's Suffrage (CLWS) takes place. CLWS was founded by the Reverend Claude Hinscliffe in 1909. Hinscliffe argued the objective was "to secure for women the Parliamentary Vote as it is or may be granted to men; to use the power thus obtained to establish equality of rights and opportunities between the sexes, and to promote the social and industrial well-being of the community."

His intention was to: "band together, on a non-party basis, Suffragists of every shade of opinion who are Church people in order to secure for women the vote in Church and State, as it is or may be granted to men." Later he stated that: "The methods of the League are Devotional and Educational." The following year Maude Royden became secretary of the CLWS.Other members included Margaret Nevinson, Edith Mansell Moullin, Florence Canning, Minnie Baldock, Clare Mordan, Olive Wharry and Katherine Harley.

Florence Canning was elected as Chairman of the Executive of the Church League for Women's Suffrage (CLWS) in early 1912. By 1913 the CLWS had 103 branches and 5,080 members. It faced a great deal of hostility from the Church establishment. The Church Times reported a H. W. Hill as saying: "For any sane person the thing is so absolutely grotesque that he must refuse to discuss it. The monstrous regiment of women in politics would be bad enough but the monstrous regiment of priestesses would be a thousandfold worse."

After the First World War the Church League for Women's Suffrage changed its name to the League of the Church Militant and campaigned for the ordination of women.

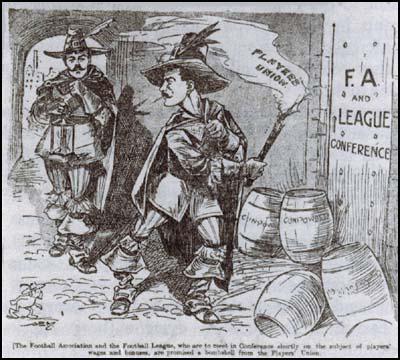

On the day in 1907 a meeting of football players took place to discuss forming a more militant trade union at the Imperial Hotel, Manchester. .Billy Meredith and several colleagues at Manchester United, including Charlie Roberts, Charlie Sagar, Herbert Burgess and Sandy Turnbull, decided to form Association Football Players Union (AFPU). Also at the meeting were players from Manchester City, Newcastle United, West Bromwich Albion and Sheffield United,.

Herbert Broomfield was appointed as the new secretary of the AFPU. It was decided to charge an entrance fee of 5s plus subs of 6d a week. Billy Meredith chaired meetings in London and Nottingham and within a few weeks the majority of players in the Football League had joined the union. This included Jim Lawrence and Colin Veitch of Newcastle United who were to become important figures in the AFPU. Evelyn Lintott, who came from a wealthy family and therefore played as an amateur, joined the AFPU and later became its chairman.

when he created the Association Football Players Union (January 1909)

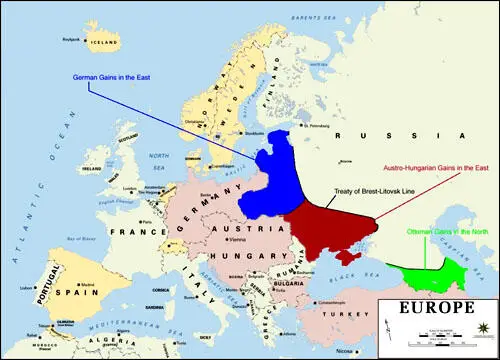

On the day in 1917 Russia and the Central Powers sign an armistice at Brest-Litovsk. After the Russian Revolution Lenin demobilized the Russian Army and announced that he planned to seek an armistice with Germany. In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty.

Trotsky commented: "The circumstances of history willed that the delegates of the most revolutionary regime ever known to humanity should sit at the same diplomatic table with the representatives of the most reactionary caste among all the ruling classes. How greatly our opponents feared the explosive power of their negotiations with the Bolsheviks was shown by their readiness to break off the negotiations rather than transfter them to a neutral country."

Arthur Ransome reported in The Daily News. "I wonder whether the English people realize how great is the matter now at stake and how near we are to witnessing a separate peace between Russia and Germany, which would be a defeat for German democracy in its own country, besides ensuring the practical enslavement of all Russia. A separate peace will be a victory, not for Germany, but for the military caste in Germany. It may mean much more than the neutrality of Russia. If we make no move it seems possible that the Germans will ask the Russians to help them in enforcing the Russian peace terms on the Allies."

Trotsky later wrote: "It was obvious that going on with the war was impossible. On this point there was not even a shadow of disagreement between Lenin and me. But there was another question. How had the February revolution, and, later on, the October revolution, affected the German army? How soon would any effect show itself? To these questions no answer could as yet be given. We had to try and find it in the course of the negotiations as long as we could. It was necessary to give the European workers time to absorb properly the very fact of the Soviet revolution." He hoped that Russia's socialist revolution would spread to Germany. This idea was reinforced when Trotsky heard the rumour on 21st January 1918, that a workers' soviet headed by Karl Liebknecht had been established in Berlin. This story was untrue as Liebknecht was still in a German prison.

Leon Trotsky recalled in his autobiography: "On 21st February, we received new terms from Germany, framed, apparently, with the direct object of making the signing of peace impossible. By the time our delegation returned to Brest-Litovsk, these terms, as is well known, had been made even harsher. All of us, including Lenin, were of the impression that the Germans had come to an agreement with the Allies about crushing the Soviets, and that a peace on the western front was to be built on the bones of the Russian revolution."

Lenin continued to argue for a peace agreement, whereas his opponents, including Leon Trotsky, Nickolai Bukharin, Andrey Bubnov, Alexandra Kollontai, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek and Moisei Uritsky, were in favour of a "revolutionary war" against Germany. This belief had been encouraged by the German demands for the "annexations and dismemberment of Russia". In the ranks of the opposition was Lenin's close friend, Inessa Armand, who had surprisingly gone public with her demands for continuing the war with Germany.

After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers and signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "Russia had lost the Ukraine, Finland, her Polish and Baltic territories. In the Caucasus she had to make territorial concessions to Turkey... Three centuries of Russian Territorial expansion was undone."

Trotsky later admitted that he was totally against signing the agreement as he thought that by continuing the war with the Central Powers it would help encourage socialist revolutions in Germany and Austria: "Had we really wanted to obtain the most favourable peace, we would have agreed to it as early as last November. But no one raised his voice to do it. We were all in favour of agitation, of revolutionizing the working classes of Germany, Austria-Hungary and all of Europe."

Herbert Sulzbach recorded in his diary: "The final peace treaty has been signed with Russia. Our conditions are hard and severe, but our quite exceptional victories entitle us to demand these, since our troops are nearly in Petersburg, and further over on the southern front, Kiev has been occupied, while in the last week we have captured the following men and items of equipment: 6,800 officers, 54,000 men, 2,400 guns, 5,000 machine-guns, 8,000 railway trucks, 8,000 locomotives, 128,000 rifles and 2 million rounds of artillery ammunition. Yes, there is still some justice left, and the state which was first to start mass murder in 1914 has now, with all its missions, been finally overthrown."

Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belorus, and Ukraine now became independent countries. The treaty deprived "Russia of a territory nearly as large as Austria-Hungary and Turkey combined, with 56,000,000 inhabitants, or 32 per cent of her whole population; a third of her railway mileage, 73 per cent of her total iron ore, 89 per cent of her total coal production; and more than 5,000 factories and industrial plants. Moreover, Russia was obliged to pay Germany an indemnity of six billion marks." The historian, John Wheeler-Bennett commented that the treaty was a "humiliation without precedent or equal in modern history."

On the day in 1927 the Ford Motor Company unveils the Ford Model A as its new automobile. By February 4, 1929, one million Model As had been sold, and by July 24, two million. The range of body styles ran from the Tudor at US$500 (in grey, green, or black) ($10,534 in 2021 dollars to the town car with a dual cowl at US$1,200 ($20,862 in 2021 dollars. In March 1930, Model A sales hit three million, and there were nine body styles available. Model A production ended in March 1932, after 4,858,644 had been made in all body styles.

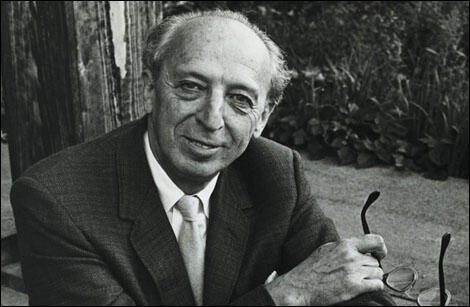

On the day in 1990 Aaron Copland, American composer died. Copland was born in New York City on 14th November, 1900. During his childhood, Copland and his family lived above his parents' Brooklyn shop, H.M. Copland's, at 628 Washington Avenue. His father, Harris Morris Copland, had no musical interest at all but his mother, Sarah Mittenthal Copland, sang and played the piano, and arranged for Aaron to have music lessons. After attending a concert by composer-pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski in 1915, he decided to become a composer. Copland took lessons in harmony, theory, and composition from Rubin Goldmark.

Copland was very interested in politics and welcomed the Russian Revolution. This brought him into conflict with his father, who was a loyal supporter of the Democratic Party. Despite his father's objections, Copland became close friends with active members of the Socialist Party of America.

In 1920 Copland moved to Paris where he studied under Nadia Boulanger at the American Academy at Fontainebleau. He had initial doubts about working with Boulanger: "No one to my knowledge had ever before thought of studying with a woman." He soon realised that she was an outstanding teacher and stayed with her until 1924.

On his return to New York City he rented a studio apartment on the Upper West Side. He received two Guggenheim Fellowships and survived on some part-time teaching. During this period he wrote Music for the Theater (1925), Piano Concerto (1926), Piano Variations (1930) and El Salón México (1936). Copland formed the Commando Unit, which included Roger Sessions, Roy Harris, Virgil Thomson, and Walter Piston.

Copland remain active in left-wing groups and asserted the importance of mass singing as a vehicle for communicating the "day-to-day struggle of the proletariat" as part of the development of working-class movements. In articles published in the New Masses, Copland argued that "American workers needed a music appropriate to their own struggles".

In the 1930s Copland became involved in the Group Theatre that had been formed in New York City by Harold Clurman, Cheryl Crawford and Lee Strasberg. The Group was a pioneering attempt to create a theatre collective, a company of players trained in a unified style and dedicated to presenting contemporary plays. His major contribution was writing the music for Quiet City, a play written by Irwin Shaw.

As Barbara L. Tischler has pointed out: "During the following decade, Copland's explicitly political activity was transformed into an effort to incorporate American folk and popular music along with regional settings into many of his concert and stage works." His ballet scores for Billy the Kid (1938), Rodeo (1942) and Appalachian Spring (1944), all reflect the composer's interest in portraying regional history in music. His left-wing politics was highlighted in his composition, Fanfare for the Common Man (1942).

Copland was a great admirer of Abraham Lincoln and Lincoln Portrait was written as part of the Second World War patriotic war effort. The work includes the reading of excerpts of Abraham Lincoln's great speeches, including the Gettysburg Address. The first performance was by the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on 14th May 1942.

Copland's growing reputation as a composer resulted in him being commissioned to write the music for several films including The City (1939), Of Mice and Men (1940), Our Town (1940), The North Star (1943), The Cummington Story (1945), The Heiress (1949) and The Red Pony (1949).

Copland remained interested in politics and in the 1948 Presidential Election he supported Henry Wallace and the Progressive Party. However, he was a strong critic of Joseph Stalin and his government. He decried the lack of artistic freedom in the Soviet Union and argued that censorship deprived artists of "the immemorial right of the artist to be wrong".

In June, 1950, three former FBI agents and a right-wing television producer, Vincent Harnett, published Red Channels, a pamphlet listing the names of 151 writers, directors and performers who they claimed had been members of subversive organizations before the Second World War but had not so far been blacklisted. The names had been compiled from FBI files and a detailed analysis of the Daily Worker, a newspaper published by the American Communist Party. The list included the name of Aaron Copland.

A free copy of Red Channels was sent to those involved in employing people in the entertainment industry. All those people named in the pamphlet were blacklisted until they appeared in front of the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and convinced its members they had completely renounced their radical past. This ended Copland's commissions from Hollywood and so he concentrated on other work such as an opera, The Tender Land (1954), Piano Fantasy (1957), Connotations for Orchestra (1962) and Inscape (1967).