Spartacus Blog

Child Labour and Freedom of the Individual

Richard Arkwright was a wig-maker in Bolton. Arkwright's work involved him travelling the country collecting people's discarded hair. In September 1767 Arkwright met John Kay, a clockmaker, from Warrington, who had been busy for some time trying to produce a new spinning-machine with another man, Thomas Highs of Leigh. Kay and Highs had run out of money and had been forced to abandon the project. Arkwright was impressed by Kay and offered to employ him to make this new machine.

Arkwright also recruited other local craftsman, including Peter Atherton, to help Kay in his experiments. According to one source: "They rented a room in a secluded teacher's house behind some gooseberry bushes, but they were so secretive that the neighbours were suspicious and accused them of sorcery, and two old women complained that the humming noises they heard at night must be the devil tuning his bagpipes." (1)

As the economic historian, Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, has pointed out, Arkwright did not have any great inventive ability, but "had the force of character and robust sense that are traditionally associated with his native county - with little, it may be added, of the kindliness and humour that are, in fact, the dominant traits of Lancashire people." (2)

In 1768 the team produced the Spinning-Frame and a patent for the new machine was granted in 1769. The machine involved three sets of paired rollers that turned at different speeds. While these rollers produced yarn of the correct thickness, a set of spindles twisted the fibres firmly together. The machine was able to produce a thread that was far stronger than that made by the Spinning-Jenny produced by James Hargreaves. (3)

Adam Hart-Davis has explained the way the new machine worked: "Several spinning machines were designed at about this time, but most of them tried to do the stretching and the spinning together. The problem is that the moment you start twisting the roving you lock the fibres together. Arkwright's idea was to stretch first and then twist. The roving passed from a bobbin between a pair of rollers, and then a couple of inches later between another pair that were rotating at twice the speed. The result was to stretch the roving to twice its original length. A third pair of rollers repeated the process... Two things are obvious the moment you see the wonderful beast in action. First, there are 32 bobbins along each side of each end of the water frame - 128 on the whole machine. Second, it is so automatic that even I could operate it." (4)

Arkwright needed investors to make the spinning-frame profitable. Arkwright approached a banker Ichabod Wright but he rejected the proposal because he judged that there was "little prospect of the discovery being brought into a practical state". (5) However, Wright did introduce Arkwright to Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. Strutt was a manufacturer of stockings and the inventor of a machine for the machine-knitting of ribbed stockings. (6) Strutt and Need were impressed with Arkwright's new machine and agreed to form a partnership. (7)

The Factory System

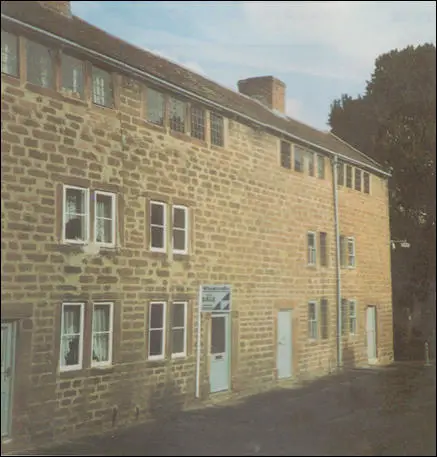

Arkwright's machine was too large to be operated by hand and so the men had to find another method of working the machine. After experimenting with horses, it was decided to employ the power of the water-wheel. In 1771 the three men set up a large factory next to the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. Arkwright later that his lawyer that Cromford had been chosen because it offered "a remarkable fine stream of water… in a an area very full of inhabitants". (8) Arkwright's machine now became known as the Water-Frame. It not only "spun cotton more rapidly but produced a yarn of finer quality". (9)

According to Adam Hart-Davis: "Arkwright's mill was essentially the first factory of this kind in the world. Never before had people been put to work in such a well-organized way. Never had people been told to come in at a fixed time in the morning, and work all day at a prescribed task. His factories became the model for factories all over the country and all over the world. This was the way to build a factory. And he himself usually followed the same pattern - stone buildings 30 feet wide, 100 feet long, or longer if there was room, and five, six, or seven floors high." (10)

In Cromford there were not enough local people to supply Richard Arkwright with the workers he needed. After building a large number of cottages close to the factory, he imported workers from all over Derbyshire. Within a few months he was employing 600 workers. Arkwright preferred weavers with large families. While the women and children worked in his spinning-factory, the weavers worked at home turning the yarn into cloth. (11)

A local journalist wrote: "Arkwright's machines require so few hands, and those only children, with the assistance of an overlooker. A child can produce as much as would, and did upon an average, employ ten grown up persons. Jennies for spinning with one hundred or two hundred spindles, or more, going all at once, and requiring but one person to manage them. Within the space of ten years, from being a poor man worth £5, Richard Arkwright has purchased an estate of £20,000; while thousands of women, when they can get work, must make a long day to card, spin, and reel 5040 yards of cotton, and for this they have four-pence or five-pence and no more." (12)

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) has argued that it was poverty that forced children into factories: "Poor families living close to a subsistence wage were often forced to draw on more diverse sources of income and had little choice over whether their children worked." (13) Michael Anderson has pointed out, that parents "who otherwise showed considerable affection for their children... were yet forced by large families and low wages to send their children to work as soon as possible." (14)

The youngest children in the textile factories were usually employed as scavengers and piecers. The job of the piecers had to lean over the spinning-machine to repair the broken threads. One observer wrote: "The work of the children, in many instances, is reaching over to piece the threads that break; they have so many that they have to mind and they have only so much time to piece these threads because they have to reach while the wheel is coming out." (15)

Edward Baines' book The History of the Cotton Manufacture (1835)

Scavengers had to pick up the loose cotton from under the machinery. This was extremely dangerous as the children were expected to carry out the task while the machine was still working. David Rowland, worked as a scavenger in Manchester: "The scavenger has to take the brush and sweep under the wheels, and to be under the direction of the spinners and the piecers generally. I frequently had to be under the wheels, and in consequence of the perpetual motion of the machinery, I was liable to accidents constantly. I was very frequently obliged to lie flat, to avoid being run over or caught." (16)

John Fielden, a factory owner, admitted that a great deal of harm was caused by the children spending the whole day on their feet: "At a meeting in Manchester a man claimed that a child in one mill walked twenty-four miles a day. I was surprised by this statement, therefore, when I went home, I went into my own factory, and with a clock before me, I watched a child at work, and having watched her for some time, I then calculated the distance she had to go in a day, and to my surprise, I found it nothing short of twenty miles." (17)

Unguarded machinery was a major problem for children working in factories. One hospital reported that every year it treated nearly a thousand people for wounds and mutilations caused by machines in factories. Michael Ward, a doctor working in Manchester told a parliamentary committee: "When I was a surgeon in the infirmary, accidents were very often admitted to the infirmary, through the children's hands and arms having being caught in the machinery; in many instances the muscles, and the skin is stripped down to the bone, and in some instances a finger or two might be lost. Last summer I visited Lever Street School. The number of children at that time in the school, who were employed in factories, was 106. The number of children who had received injuries from the machinery amounted to very nearly one half. There were forty-seven injured in this way." (18)

William Blizard lectured on surgery and anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons. He was especially concerned about the impact of this work on young females: "At an early period the bones are not permanently formed, and cannot resist pressure to the same degree as at a mature age, and that is the state of young females; they are liable, particularly from the pressure of the thigh bones upon the lateral parts, to have the pelvis pressed inwards, which creates what is called distortion; and although distortion does not prevent procreation, yet it most likely will produce deadly consequences, either to the mother or the child, when the period." (19)

Elizabeth Bentley, who came from Leeds, was another witness that appeared before the committee. She told of how working in the card-room had seriously damaged her health: "It was so dusty, the dust got up my lungs, and the work was so hard. I got so bad in health, that when I pulled the baskets down, I pulled my bones out of their places." Bentley explained that she was now "considerably deformed". She went on to say: "I was about thirteen years old when it began coming, and it has got worse since." (20)

Samuel Smith, a doctor based in Leeds explained why working in the textile factories was bad for children's health: "Up to twelve or thirteen years of age, the bones are so soft that they will bend in any direction. The foot is formed of an arch of bones of a wedge-like shape. These arches have to sustain the whole weight of the body. I am now frequently in the habit of seeing cases in which this arch has given way. Long continued standing has also a very injurious effect upon the ankles. But the principle effects which I have seen produced in this way have been upon the knees. By long continued standing the knees become so weak that they turn inwards, producing that deformity which is called 'knock-knees' and I have sometimes seen it so striking, that the individual has actually lost twelve inches of his height by it." (21)

appeared in Trollope's Michael Armstrong (1840)

John Reed later recalled his life aa a child worker at Cromford Mill: "I continued to work in this factory for ten years, getting gradually advanced in wages, till I had 6s. 3d. per week; which is the highest wages I ever had. I gradually became a cripple, till at the age of nineteen I was unable to stand at the machine, and I was obliged to give it up. The total amount of my earnings was about 130 shillings, and for this sum I have been made a miserable cripple, as you see, and cast off by those who reaped the benefit of my labour, without a single penny." (22)

Robert Owen and New Lanark

In 1810 Robert Owen purchased four textile factories owned by David Dale in New Lanark for £60,000. Under Owen's control, the Chorton Twist Company expanded rapidly. However, Owen was not only concerned with making money, he was also interested in creating a new type of community at New Lanark. He became highly critical of factory owners to employ young children: "In the manufacturing districts it is common for parents to send their children of both sexes at seven or eight years of age, in winter as well as summer, at six o'clock in the morning, sometimes of course in the dark, and occasionally amidst frost and snow, to enter the manufactories, which are often heated to a high temperature, and contain an atmosphere far from being the most favourable to human life, and in which all those employed in them very frequently continue until twelve o'clock at noon, when an hour is allowed for dinner, after which they return to remain, in a majority of cases, till eight o'clock at night." (23)

Owen set out to make New Lanark an experiment in philanthropic management from the outset. Owen believed that a person's character is formed by the effects of their environment. Owen was convinced that if he created the right environment, he could produce rational, good and humane people. Owen argued that people were naturally good but they were corrupted by the harsh way they were treated. For example, Owen was a strong opponent of physical punishment in schools and factories and immediately banned its use in New Lanark. (24)

David Dale had originally built a large number of houses close to his factories in New Lanark. By the time Owen arrived, over 2,000 people lived in New Lanark village. One of the first decisions took when he became owner of New Lanark was to order the building of a school. Owen was convinced that education was crucially important in developing the type of person he wanted. He stopped employing children under ten and reduced their labour to ten hours a day. The young children went to the nursery and infant schools that Owen had built. Older children worked in the factory but also had to attend his secondary school for part of the day. (25)

George Combe, an educator who was unsympathetic to Owen's views generally, visited New Lanark during this period. "We saw them romping and playing in great spirits. The noise was prodigious, but it was the full chorus of mirth and kindliness." Combe explained that Owen had ordered £500 worth of "transparent pictures representing objects interesting to the youthful mind" so that children could "form ideas at the same time that they learn words". Combe went on to argue that the greatest lessons Owen wished the children to learn were "that life may be enjoyed, and that each may make his own happiness consistent with that of all the others." (26)

The journalist, George Holyoake, became a great supporter of Owen's work in New Lanark: "At New Lanark he virtually or indirectly supplied to his workpeople, with splendid munificence and practical judgment, all the conditions which gave dignity to labour.... Co-operation as a form of social amelioration and of profit existed in an intermittent way before New Lanark; but it was the advantages of the stores Owen incited that was the beginning of working-class co-operation. His followers intended the store to be a means of raising the industrious class, but many think of it now merely as a means of serving themselves. Still, the nobler portion are true to the earlier ideal of dividing profits in store and workshop, of rendering the members self-helping, intelligent, honest, and generous, and abating, if not superseding competition and meanness." (27)

When Owen arrived at New Lanark children from as young as five were working for thirteen hours a day in the textile mills. Owen later explained to a parliamentary committee: "I found that there were 500 children, who had been taken from poor-houses, chiefly in Edinburgh, and those children were generally from the age of five and six, to seven to eight. The hours at that time were thirteen. Although these children were well fed their limbs were very generally deformed, their growth was stunted, and although one of the best schoolmasters was engaged to instruct these children regularly every night, in general they made very slow progress, even in learning the common alphabet." (28)

Owen's partners were concerned that these reforms would reduce profits. Frederick Adolphus Packard explained that when they complained in 1813 he replied: "that if he was to continue to act as managing partner he must be governed by the principles and practices." Unable to convince them of the wisdom of these reforms, Owen decided to borrow money from Archibald Campbell, a local banker, in order to buy their share of the business. Later, Owen sold shares in the business to men who agreed with the way he ran his factory. This included Jeremy Bentham and Quakers such as William Allen, Joseph Foster and John Walker. (29)

Robert Owen hoped that the way he treated children at his New Lanark would encourage other factory owners to follow his example. It was therefore important for him to publicize his activities. He wrote several books including The Formation of Character (1813) and A New View of Society (1814). In these books he demanded a system of national education to prevent idleness, poverty, and crime among the "lower orders". He also recommended restricting "gin shops and pot houses, the state lottery and gambling, as well as penal reform, ending the monopolistic position of the Church of England, and collecting statistics on the value and demand for labour throughout the country." (30)

In January 1816, Robert Owen made a speech at a meeting in New Lanark: "When I first came to New Lanark I found the population similar to that of other manufacturing districts... there was... poverty, crime and misery... When men are in poverty they commit crimes.., instead of punishing or being angry with our fellow-men... we ought to pity them and patiently to trace the causes... and endeavour to discover whether they may not be removed. This was the course which I adopted". (31)

Parliament and Child Labour

Robert Owen sent detailed proposals to Parliament about his ideas on factory reform. This resulted in Owen appearing before Robert Peel and his House of Commons committee in April, 1816. Owen explained that when he took over the company they employed children as young as five years old: "Seventeen years ago, a number of individuals, with myself, purchased the New Lanark establishment from Mr. Dale.... I came to the conclusion that the children were injured by being taken into the mills at this early age, and employed for so many hours; therefore, as soon as I had it in my power, I adopted regulations to put an end to a system which appeared to me to be so injurious". (32)

The government was unwilling to restrict the freedom of the industrialists who were now having an increasing control over Parliament. This is reflected in those giving evidence before Lord Kenyon's House of Lords Committee in 1818. Edward Holme had worked for 24 hours as a doctor in Manchester and was employed by local factory owners to look after the health of their staff. He was asked: "In what state of health did you find the persons employed?" Holme replied: "They were in good health generally... They are as healthy as any other part of the working classes of the community." He was asked if he would "permit a child of eight years old, for instance, to be kept standing for twelve hours a day?" He replied that: "My conclusion would be this: the children I saw were all in health; if they were employed during those ten, twelve, or fourteen hours, and had the appearance of health, I should still say it was not injurious to their health." (33)

Dr. William Whatton was involved in examining the workers at Peter Appleton's factory in the city. Whatton insisted that the children he examined showed no signs of being in poor health. He was asked: "If a child was of a delicate constitution, would you think twelve hours was too long to keep him at work?" Whatton replied: "The labour is so moderate it can scarcely be called labour at all; and under those circumstances I should not think there would be any injury from it." When he was given the example "would not the instance of a young person of eight years old, kept standing for twelve hours during the day, be likely to produce a ricketty appearance?" he answered no. (34)

Dr. Thomas Turner, the house surgeon and apothecary of the Manchester Workhouse, pointed out he had recently examined 1125 workers in two different factories and the "general appearance was good and healthy". However, he was unwilling to answer the question: "Do you think it would benefit a child's health of eight years old to be kept twelve hours upon his legs?" This led to the question: "Would you think a child of eight years old being kept fourteen hours upon its legs without any intermission, would or would not that be dangerous, if he was kept standing the whole time?". Dr Turner replied: "I think it would be fatiguing; whether the health would be materially injured by it, I am not prepared to say." He was then asked: "You can form no opinion whether a child of eight years of age being kept standing fourteen hours, without intermission, would be injurious to his health or not?" He replied: "I am not prepared to answer." (35)

The evidence provided by this doctors was used by Parliament to decide not to pass legislation against child labour. The campaign continued and Parliament eventually passed the 1833 Factory Act that prohibited the employment of children younger than nine years of age. "The working day was to start at 5.30 a.m. and cease at 8.30 p.m. A young person (aged thirteen to eighteen) might not be employed beyond any period of twelve hours, less one and a half for meals; and a child (aged nine to thirteen) beyond any period of nine hours." (36)

It was the beginning of the struggle between the freedom of the employers and the freedom of the individual working for them. Until all adults achieved the vote, it was an unfair fight. Even after adult suffrage was achieved Parliament invariably placed the rights of the employer over that of the workforce.

John Simkin (26th July, 2021)

References

(1) Adam Hart-Davis, Richard Arkwright, Cotton King (10th October 1995)

(2) Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, The Industrial Revolution 1760-1830 (1948) page 58

(3) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) page 290

(4) Adam Hart-Davis, Richard Arkwright, Cotton King (10th October 1995)

(5) R. S. Fitton, The Arkwrights: Spinners of Fortune (1989) page 27

(6) Gavin Weightman, The Industrial Revolutionaries (2007) page 11

(7) J. J. Mason, Richard Arkwright : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(8) R. S. Fitton, The Arkwrights: Spinners of Fortune (1989) page 28

(9) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938) page 290

(10) Adam Hart-Davis, Richard Arkwright, Cotton King (10th October 1995)

(11) Thomas Southcliffe Ashton, The Industrial Revolution 1760-1830 (1948) page 59

(12) Ralph Mather, An Impartial Representation of the Case of the Poor Cotton Spinners in Lancashire (1780)

(13) Peter Kirby, Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) page 28

(14) Michael Anderson, Family Structure in Nineteenth-Century Lancashire (1971) page 76

(15) James Turner, interviewed by Michael Sadler's Parliamentary Committee (17th April 1832)

(16) David Rowland interviewed by Michael Sadler's Parliamentary Committee (10th July 1832)

(17) John Fielden, speech in the House of Commons (9th May 1836)

(18) Dr. Ward from Manchester was interviewed about the health of textile workers on 25th March, 1819.

(19) Sir William Blizard was interviewed by Michael Sadler's House of Commons Committee on 21st May, 1832.

(20) Elizabeth Bentley was interviewed by Michael Sadler and his House of Commons Committee on 4th June, 1832.

(21) Samuel Smith, interviewed by Michael Sadler's House of Commons Committee on 16th July, 1832.

(22) William Dodd interviewed John Reed from Arkwright's Cromford's factory in 1842.

(23) Robert Owen, Observations on the Effect of the Manufacturing System (1815) page 9

(24) Gregory Claeys, Robert Owen : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(25) Robert Owen, Robert Peel's House of Commons Committee (26th April, 1816)

(26) Harold Silver, Owen's Reputation as an Educationalist, included in Robert Owen: Prophet of the Poor (1971) page 269

(27) George Holyoake, Sixty Years of an Agitator's Life (1892) page 118

(28) Robert Owen, Robert Peel's House of Commons Committee (26th April, 1816)

(29) Frederick Adolphus Packard, Life of Robert Owen (1866) page 82

(30) Gregory Claeys, Robert Owen : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(31) Robert Owen, speech in New Lanark (1st January, 1816)

(32) Robert Owen, Robert Peel's House of Commons Committee (26th April, 1816)

(33) Edward Holme, interviewed by Lord Kenyon's House of Lords Committee (22nd May, 1818)

(34) Dr. William Whatton, interviewed by Lord Kenyon's House of Lords Committee (25th May, 1818)

(35) Dr. Thomas Turner, interviewed by Lord Kenyon's House of Lords Committee (1st June, 1818)

(36) Peter Kirby, Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003) page 104

Previous Posts

Covid-19 and the Concept of Freedom (26th July, 2021)

Don Reynolds and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy (15th June, 2021)

Richard Nixon and the Conspiracy to kill George Wallace in 1972 (5th May, 2021)

The Connections between Watergate and the JFK Assassination (2nd April, 2021)

The Covid-19 Pandemic: An Outline for a Public Inquiry (4th February, 2021)

Why West Ham did not become the best team in England in the 1960s (24th December, 2000)

The Lyndon Baines Johnson Tapes and the John F. Kennedy Assassination (9th November, 2020)

It is Important we Remember the Freedom Riders (11th August, 2020)

Dominic Cummings, Niccolò Machiavelli and Joseph Goebbels (12th July, 2020)

Why so many people in the UK have died of Covid-19 (14th May, 2020)

Why the coronavirus (Covid-19) will probably kill a higher percentage of people in the UK than any other country in Europe.. (12th March, 2020 updated 17th March)

Mandy Rice Davies and Christine Keeler and the MI5 Honey-Trap (29th January, 2020)

Robert F. Kennedy was America's first assassination Conspiracy Theorist (29th November, 2019)

The Zinoviev Letter and the Russian Report: A Story of Two General Elections (24th November, 2019)

The Language of Right-wing Populism: Adolf Hitler to Boris Johnson (11th October, 2019)

The Political Philosophy of Dominic Cummings and the Funding of the Brexit Project (15th September, 2019)

What are the political lessons to learn from the Peterloo Massacre? (19th August, 2019)

Crisis in British Capitalism: Part 1: 1770-1945 (9th August, 2019)

Richard Sorge: The Greatest Spy of the 20th Century? (29th July, 2020)

The Death of Bernardo De Torres (26th May, 2019)

Gas Masks in the Second World War killed more people than they saved (9th May, 2019)

Did St Paul and St Augustine betray the teachings of Jesus? (20th April, 2019)

Stanley Baldwin and his failed attempt to modernise the Conservative Party (15th April, 2019)

The Delusions of Neville Chamberlain and Theresa May (26th February, 2019)

The statement signed by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Kathleen Kennedy Townsend (20th January, 2019)

Was Winston Churchill a supporter or an opponent of Fascism? (16th December, 2018)

Why Winston Churchill suffered a landslide defeat in 1945? (10th December, 2018)

The History of Freedom Speech in the UK (25th November, 2018)

Are we heading for a National government and a re-run of 1931? (19th November, 2018)

George Orwell in Spain (15th October, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in Britain today. Jeremy Corbyn and the Jewish Chronicle (23rd August, 2018)

Why was the anti-Nazi German, Gottfried von Cramm, banned from taking part at Wimbledon in 1939? (7th July, 2018)

What kind of society would we have if Evan Durbin had not died in 1948? (28th June, 2018)

The Politics of Immigration: 1945-2018 (21st May, 2018)

State Education in Crisis (27th May, 2018)

Why the decline in newspaper readership is good for democracy (18th April, 2018)

Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party (12th April, 2018)

George Osborne and the British Passport (24th March, 2018)

Boris Johnson and the 1936 Berlin Olympics (22nd March, 2018)

Donald Trump and the History of Tariffs in the United States (12th March, 2018)

Karen Horney: The Founder of Modern Feminism? (1st March, 2018)

The long record of The Daily Mail printing hate stories (19th February, 2018)

John Maynard Keynes, the Daily Mail and the Treaty of Versailles (25th January, 2018)

20 year anniversary of the Spartacus Educational website (2nd September, 2017)

The Hidden History of Ruskin College (17th August, 2017)

Underground child labour in the coal mining industry did not come to an end in 1842 (2nd August, 2017)

Raymond Asquith, killed in a war declared by his father (28th June, 2017)

History shows since it was established in 1896 the Daily Mail has been wrong about virtually every political issue. (4th June, 2017)

The House of Lords needs to be replaced with a House of the People (7th May, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Caroline Norton (28th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Mary Wollstonecraft (20th March, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Anne Knight (23rd February, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons Candidate: Elizabeth Heyrick (12th January, 2017)

100 Greatest Britons: Where are the Women? (28th December, 2016)

The Death of Liberalism: Charles and George Trevelyan (19th December, 2016)

Donald Trump and the Crisis in Capitalism (18th November, 2016)

Victor Grayson and the most surprising by-election result in British history (8th October, 2016)

Left-wing pressure groups in the Labour Party (25th September, 2016)

The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism (3rd September, 2016)

Leon Trotsky and Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party (15th August, 2016)

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England (7th August, 2016)

The Media and Jeremy Corbyn (25th July, 2016)

Rupert Murdoch appoints a new prime minister (12th July, 2016)

George Orwell would have voted to leave the European Union (22nd June, 2016)

Is the European Union like the Roman Empire? (11th June, 2016)

Is it possible to be an objective history teacher? (18th May, 2016)

Women Levellers: The Campaign for Equality in the 1640s (12th May, 2016)

The Reichstag Fire was not a Nazi Conspiracy: Historians Interpreting the Past (12th April, 2016)

Why did Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst join the Conservative Party? (23rd March, 2016)

Mikhail Koltsov and Boris Efimov - Political Idealism and Survival (3rd March, 2016)

Why the name Spartacus Educational? (23rd February, 2016)

Right-wing infiltration of the BBC (1st February, 2016)

Bert Trautmann, a committed Nazi who became a British hero (13th January, 2016)

Frank Foley, a Christian worth remembering at Christmas (24th December, 2015)

How did governments react to the Jewish Migration Crisis in December, 1938? (17th December, 2015)

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)