Bomb Disposal Unit, Air Raid Wardens and the British Media

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) had the problem of dealing with unexploded bombs (UXB). A warden would arrange for all premises to be evacuated and all roads within a 600 yard radius of the unexploded bomb. At the beginning of the war it is estimated that one in ten bombs during the early days of the Blitz were "duds". When the ARP discovered a German bomb they would inform the Bomb Disposal Unit (BDU) and skilled men from the Royal Engineers would be sent to remove the fuse. (1)

On 12th September 1940, a 2,200-pound bomb had fallen close to St Paul's Cathedral and lay embedded in the ground near the front of the building. Its removal was a highly dangerous task for the bomb disposal squad, and took several days. Finally, the eight foot long missile was removed and taken on a lorry to what became known as the "bomb cemetery" on Hackney Marshes. The streets on its route was cleared in case it went off prematurely. on 15th September it was exploded in controlled conditions, where it made a crater one hundred feet in diameter. (2)

Bomb Disposal Unit

By September 1940 there were 3,759 UXBs in London. At first the main reason for this was faulty mechanism. However, within a few weeks it became clear that Germany had changed its strategy. Some bombs had been fitted with a sophisticated time-delay mechanism instead of a simple impact fuse. This was to ensure that the bombs would cause maximum havoc in the area where they fell, with premises evacuated and roads closed until they could be defused or moved to the "bomb cemetery". (3)

People got used to this lurking hazard and after a while they refused to have their life interrupted by warnings of an unexploded bomb. Vere Hodgson, who helped to run a local charity in Notting Hill Gate, pointed out that when a large section of Hyde Park was cordoned off, with seats resting against the rope carrying placards marked "BEWARE - UXB!". However, Hodgson pointed out that people were peacefully sitting on the seats and some had penetrated the barrier and were relaxing on the grass inside. (4)

Frederick Leighton-Morris removed a 50kg bomb from his neighbour's flat in Jermyn Street, Mayfair, and decided to dump it in St James's Park. He was arrested when he put it down to have a well-earned rest. The magistrate praised his courage but fined him £100. You cannot decide, he was told, "in which part of London a delayed action bomb should go off". On appeal the fine was reduced to a more modest £5. (5) In court he pointed out that he had been rejected from national service for health reasons, but it was later reported that as a result of the case he was allowed to join the Royal Engineers. (6)

In September, 1940, George VI announced that "in order that they (Civil Defence workers) should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all weeks of civilian life" for valour on the home front, as there were medals for those at the battlefront. The George Cross was intended to be the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, which was awarded for "acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger" Most of the medals went to members of the bomb disposal squads. (7)

At the beginning of the war conscientious objectors who refused to join the armed forces became members of the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC). It consisted of fourteen companies totaling 6,766 men and took part in all aspects of the war effort, apart from those that required the handling of weapons. By the end of 1940, 123 members of the BDU's had been killed and 67 wounded. It was therefore decided in January 1941, to send two companies of the NCC to London to clear bomb sites. (8)

Christopher Wren, was a member of the NCC who was sent to London: "I thought that it would be very good to destroy armaments and at the same time protect people. Both aspects seemed to fit with why I had become a non-combatant. The training was minimal. We went to Chester and were under canvas on the racecourse… We were told we would be going to London because there was more to be done down there… A few weeks later we were sent to Chelsea Barracks for real training. We really enjoyed that. It was with the Royal Engineers and everything was enjoyable. No prejudice at all." (9)

Tony White was another conscientious objector who carried out bomb-disposal work. "It was doing something constructive in the sense that you were digging out bombs that were meant to harm, immunizing them, and you could see it as a direct service for the community. But the major reason was my proving something to myself, that I wasn't ‘dodging the column'… I didn't want to escape the risk and here was a chance to prove my sincerity, not in the front line but dangerous… There were several 1,000 pounders that we got, about 4 or 5 feet long, they were a pretty good size. They were heavy of course, and we got them out by winching them out, with a tripod type of rig to haul them out. We'd take them away and try to neutralize them. You'd screw in and make a hole in the casing trying not to disturb the fuse… that job had to be done very carefully, and then we'd inject steam which would neutralize the power or the explosive and then one could remove the fuse safely. And then the officer would retreat to what was theoretically a safe distance and then explode it with an electrical device. This was when the thing could explode before the officer had got far enough away, he was always the one at the greatest risk and we did suffer casualties. You were never sure when you moved the bomb out of its hole… if you'd disturbed the mechanism and there was always the risk that the thing might explode." (10)

The bomb-disposal unit had the skilled and dangerous task of removing the device of making it safe. One of the major problems was the bombs usually penetrated through earth and tarmac to lie deep underground, making it extremely difficult and perilous to defuse them. As Juliet Gardiner has pointed out: "Throughout the war, bomb disposal was a perpetual deadly game of being one step ahead. As soon as the sappers worked out how one fuse could be neutralized, it seemed the Germans would adapt it or invent another that would test the ingenuity - and courage - of the soldiers (and those 350 or so commanding officers who had volunteered to help) to the very limit." (11)

Dr. Herbert J. Gough, was appointed as Director-General of Scientific Research. When an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station. Dr. Gough went to see it and took his friend, Charles Howard, 20th Duke of Suffolk, with him. "The highly-dangerous 'game' of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination." (12)

Duke of Suffolk's detachment consisted of himself, his secretary Eileen Beryl Morden, and his chauffeur, Fred Hards. Over the next few months successfully dealt with 34 unexploded bombs. He was described as being "tall and debonair, often wearing a stetson, fawn duffel coat and sporting a matinee idol moustache, Howard would smoke with his 9-inch cigarette holder as he pondered the latest UXB." (13) Harold Macmillan met Suffolk in 1940: "I have had the good fortune to meet many gallant officers and brave men, but I have never known such a remarkable combination in a single man of courage, expert knowledge and indefinable charm." (14)

Richard Tunbridge, tells the story of how his grandfather encountered the Duke of Suffolk in the spring of 1941: "My grandparent's shop had been damaged on numerous occasions but they kept it open as they were the only newsagents functioning in a heavily bombed area. Getting stock was very difficult and my grandfather used to travel all over London to find supplies, often bringing these back on a handmade barrow. They were about to give up when a remarkable event occurred. They woke up one morning to local pandemonium; an unexploded parachute landmine was hanging from a building. Everyone rushed into the shelter but later that morning a bizarre event occurred. A limousine pulled up and two men and a woman got out and came into the shelter. This smartly dressed trio announced themselves as Lord Howard, Earl of Suffolk, his chauffeur and his secretary. Everyone was amazed when they said they were the ‘Holy Trinity' bomb disposal team! They changed into overalls and went about defusing the landmine with the secretary taking detailed notes for future reference." (15)

On Tuesday, 12th May, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the Belvedere Marshes, just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty. The bomb exploded at 3.20 pm and created a crater 5 ft in diameter. Suffolk was killed immediately. Rescuers found "Beryl Morden in an extremely serious condition. Fred Hands had managed to drag himself a few yards and died calling for Suffolk... Beryl, who had been in the service of the Earl for eleven months, sadly succumbed to her injuries and died in the ambulance." (16)

One newspaper reported that throughout the Second World War "countless lives were saved by a group of selfless, silent men - the volunteer heroes of bomb disposal units, the scientists and engineers who worked continuously in the shadow of sudden death. Many of these brave men did lose their lives in the pursuit of their hazardous work, but there were always others ready and willing to take their place." (17)

Between 1940 and 1945, no fewer than 50,000 unexploded bombs were examined and disposed of in Great Britain. The deaths of members of the Bomb Disposal Unit did not end when peace was achieved in 1945. Unexploded bombs continued to be discovered. By 1947, 490 members of the BDU had been killed in the battle to extract those "great, torpid, iron pigs from the holes" and render them harmless. (18)

Air Raid Wardens

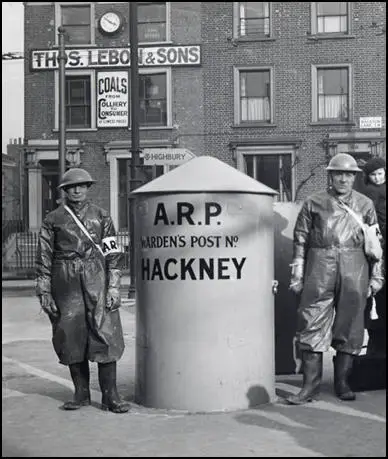

In September 1935, the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin, published a circular entitled Air Raid Precautions (ARP) inviting local authorities to make plans to protect their people in event of a war. Some towns responded by arranging the building of public air raid shelters. These shelters were built of brick with roofs of reinforced concrete. However, some local authorities ignored the circular and in April 1937 the government decided to create an Air Raid Wardens' Service. (19)

Initially, volunteers tended to be male, middle-aged and middle-class. "The unskilled working class provided the fewest, probably more because of transport problems and the physical strain of their daily occupations than for lack of patriotism. ARP posts were manned by three to six wardens, though some were considerably larger. It was suggested that London alone needed 200,000 wardens, of whom some 16,000 would be full-time and paid (£3 a week). However, progress was slow and volunteer numbers were disappointing. (20)

The ARP system was criticised by newspapers for wasting money: "We are constantly hearing stories of patriotic citizens volunteering for full-time service as wardens, neither wanting nor expecting payment, and finding themselves placed on the ARP Committee's payroll. There seems to be little room to doubt that many posts have been filled by paid wardens when there were volunteers available... it will be an abrogation of the great voluntary spirit of the movement... to turn public-spirited volunteers into hirelings." (21)

Others accused wardens for being paid money for very little work: "Thousands of men, many in good jobs, are drawing £3 a week as Air Raid wardens; hundreds of girls and youths are getting good pay for doing nothing; fantastic sums are being paid to motorists for merely putting their vehicles at the disposal of the ARP or ambulance work; demolition squads are standing in the streets twenty-four hours a day twiddling their thumbs; auxiliary fireman are also on the job; 'log-rolling' and intrigue are rampant." (22)

John Langdon-Davies argued in 1939 that the British government should reassess its policy on ARP: "If we are to become ARP minded, we must realise that the peace-time life to which we have become reconciled must be altered fundamentally. Real ARP does not mean digging a large number of shelters and then going on living as we have done heretofore. It means altering our cities and our way of living in them so that at a moment's notice they may become part of the front line trenches in a war thrust upon us by the air bandits of international Fascism... The object of air bombardment is not to hit military objectives but to attack the nerve centres of the man in the street. We must prepare our defence now by letting everybody know exactly what to expect from an air raid and by training them so withstand the nervous shock such a raid entails." (23)

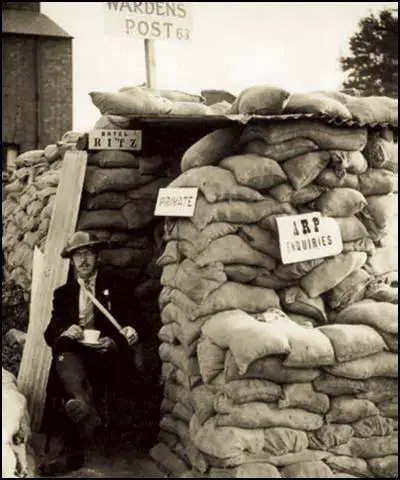

The ratio of ARP wardens varied from city to city, borough to borough, but for most the standard was ten wardens' posts to the square mile. About nine-tenths of ARP wardens were part-timers who came on duty after they finished their day's work, and one in six was a woman. The warden post might be a shop, hall or basement, or even the front room of one of the wardens. The area would be divided into sectors with perhaps three to six wardens controlled by a senior warden in each sector. It was essential that a warden knew his or her sector and was often called their "patch". A good warden would know the habits of the people who lived in their sector so that when a bomb fell the emergency services could be directed at once to where survivors might be buried. (24)

The task of co-ordinating all civil defence planning was then given to Sir John Anderson, a senior civil servant and the former Governor of Bengal. In February, 1938, he was elected as the Conservative Party MP for the Combined Scottish Universities. The Anderson Committee was first convened in May 1938. Senior military personnel from all branches of the armed forces were called upon to advise the committee. These officers duly outlined all military bases, industrial areas and cities that were likely to be attacked. (25)

Anderston wrote a pamphlet, The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids (1940) where he gave advice on the services provided by the ARP: "If air raids ever come to this country… do not hesitate to ask for advice if you need it. A local Air Raid Precautions organization has been established in your district and Air Raid Wardens have been appointed to help you. For any help you need, apply to your Warden or to your local Council Offices. All windows, skylights, glazed doors or other openings in parts of the house where lights are used must be completely screened after dusk so that no light is visible from outside. All lights near an outside door must be screened. Clear the loft, attic or top floor of all inflammable material – paper, litter, lumber, etc. – to lessen the danger of fire and prevent fire from spreading." (26)

The government made money available for materials for local authorities to build public outdoor shelters, although they had to foot the bill for the construction costs. New buildings had to incorporate spaces for shelters, and employers with a workforce of fifty or more in a designated target area were obliged to provide shelter accommodation for their employees (they would receive government funding to help pay for this). Once war started the government urged local authorities to provide purpose-built public shelters, above ground heavily protected brick and concrete constructions capable of holding up to fifty people. (27)

On 1st September, 1939, the staff for the local control rooms had been called to their posts. From this point until almost the end of the war, the machinery of civil defence would remain permanently alert. Angus Calder argues in The People's War (1969): "The wardens... were exposed to abuse and ridicule. To working-class men, the wardens often appeared to be no more than lackeys of the police, a traditional enemy. A proportion of bossy and bad tempered wardens gave the whole service a bad name. With other civil defenders they trained on duty and staged mock 'incidents' in the streets. The spectacle of grown men play-acting in public still further diminished confidence in ARP; citizens were enlisted as air raid victims and painted for the part." (28)

Winston Churchill took a keen interest in these arrangements. On 1st October, 1939, he wrote to Neville Chamberlain, the prime minister, to express his concerns: "The A. R. P. (Air Raid Precautions) defences and expense are founded upon a wholly fallacious view of the degree of danger to each part of the country which they cover. Schedules should be made of the target areas and of the paths of flight by which they may be approached. In these areas there must be a large proportion of whole-time employees. London is of course the chief target, and others will readily occur. In these target areas the street-lighting should be made so that it can be controlled by the Air Wardens on the alarm signal being given; and while shelters should be hurried on with and strengthened, night and day, the people's spirits should be kept up by theatres and cinemas until the actual attack begins. Over a great part of the countryside, modified lighting should be at once allowed, and places of entertainment opened." (29)

Barbara Nixon, an actress, became a voluntary (part-time) warden. "By the time that I joined, the public was already grumbling that the full-time Civil Defence personnel were a waste of money - a set of slackers, after easy jobs... I was given a tin hat, a whistle, and a CD respirator. The Post Warden one afternoon conducted me on the tour of the seventeen public shelters in the area... I gathered that a warden's main duty was to report any bombs which fell in his area. The Post itself was in a basement of an old house. It was not strengthened in any way, but across the road was a sunk concrete pill-box, which, later, gave good proof of its strength. When 'yellow' stand-by warnings or alerts sounded, the Post Warden, or his Deputy, a messenger, and one or two other wardens moved over there, while the rest of us went off to our various sectors. The Post area was divided into six or seven of these." (30)

Wardens would report to their post when they came on or went off duty, and part-time wardens were supposed to put in about three nights a week, though this increased greatly during the Blitz. They would sit around drinking cups of tea, smoking, reading the paper, playing cards or darts, gossiping or snoozing until the yellow "stand-by" warning alert sounded and then they would leave the post to patrol the streets of their sector on foot. When the red alert sounded that meant "raiders overhead", the air raid sirens would be set-off. (31)

Frances Faviell was an ARP in London. She later wrote about her experiences in her autobiography, A Chelsea Concerto (1959): "When the siren sounded we would hurry to the shelters, ticking off the names of the residents in their areas as they arrived, then back they went to hurry and chivvy the laggards and see that those who chose to stay in their houses were all right... They carried children, old people, bundles of blankets, and the odd personal possessions which some eccentrics insisted on taking with them to the shelters." (32)

Being a warden was a very dangerous occupation. On 5th May, 1941, the Luftwaffe carried out a heavy raid on the centre of Liverpool. It left 1,741 dead and 1,065 were seriously injured. The Civil Defence services lost large number of its personnel. This included twenty-eight ARP wardens and WVS workers killed and fourteen seriously injured. However, the government, anxious not to alert the Germans to how devastating their raids on Merseyside were, the public were not told about the people who lost their lives. (33) Five days later, six air raid wardens were killed as they talked to the Reverend Stanley Tolley, the 38 year-old vicar of St Silas Church in Nunhead, near Peckham. (34)

In December 1940 Barbara Nixon decided to become a full-time warden: "I was already putting in more than the requisite number of hours and, more important, any other work that I could get entailed leaving London, which in the circumstances, I was prepared to do. I therefore applied to be paid the magnificent sum of £2 5s. a week. The Town Hall, however, had objections. First, they said they did not want any more women; then, when that argument was disposed of, they said they would not employ married women, and asked me why I wanted to work when I was married. At length, after four or five weeks, they agreed to appoint me, but said that I must go to Post 13 at the other end of the borough… I made enquiries as to what ‘13' was like. Apart from jokes about its number, what I learned was not encouraging. They were considered the toughest set of wardens in the borough. Once, they had had a woman on the strength, but she had left months ago. They did not like woman. And they had had by far the heaviest fall of bombs in the neighbourhood, half the area being completely devastated." (35)

One report, written by a senior warden, suggested that women wardens were better than male wardens at dealing with the consequences of an air raid: "I go into a house, decide who's alive and who's dead, tot up the number of victims and what is necessary in the way of fire services, ambulances, demolition etc... Women warders are better than men in most cases... They can see in a moment who is in the house because they know what to look for. If the kettle is on the stove they know the occupants are probably downstairs and have not gone to bed; if there is a cot they know there is a baby about somewhere." (36)

After an air-raid it was the responsibility of the first wardens to arrive on the scene to assess the situation. The incident was reported it "quickly, concisely and accurately to Control. He or she then began to deal with the casualties. After administering first aid all casualties had to be labeled at the incident with any information that would help in their treatment. This was written in indelible pencil on a luggage label or lipstick on the casualty's forehead. They would then stay with injured until the medical staff arrived. (37)

Stanley Rothwell worked as a warden in Lambeth: "I looked up at the wall of the house, as I lifted my torch and I could see what looked like treacle sliding down the wall. I realized what it was, and seeing that nothing could be done in the darkness, I took my squad back to the depot to report what I had seen and to prepare to come back at daybreak with shrouds and the death wagon to do the unsavory job of picking up the bits and pieces. This macabre business was to be my lot for the rest of the war. During training I had instructed my men to treat the dead with reverence and respect, but I did not think we would have to shovel them up. Now this job had to be done with a stiff yard broom, a garden rake and shovel. We had to throw buckets of water up the wall to wash it down. The only tangible things were a man's hand with a bent ring on a finger, a woman's foot in a shoe on a window sill. In one corner of the garden was a bundle of something held together with a leather strap, as I disturbed it fell to pieces steaming. It was part of a torso. The stench was something awful and it clung to my nostrils for some time after; in fact I never lost that smell until some time after the war was over.We gathered about six bags of bits and pieces; one pathetic little bundle, shapeless now, tied with bits of lace and ribbon, had been a baby." (38)

Barbara Nixon later described her reaction to the first air-raid she encountered: "As the blast of air reached me I left my saddle and sailed through the air... The tin hat on my shoulder took the impact, and as I stood up I was mildly surprised to find that I was not hurt in the least... The damage was thirty yards away, but the corner building, which had diverted some of the blast from me, was still standing. At four in the afternoon there would certainly be casualties. Now I would know whether I was going to be of any use as a warden or not, and I wanted to postpone the knowledge. I dared not run... I was not let down lightly... In the middle of the street lay the remains of a baby. It had been blown clean through the window and had burst on striking the roadway. To my intense relief, pitiful and horrible as it was, I was not nauseated, and found a torn piece of curtain in which to wrap it." (39)

Frances Faviell commented that "The stench was the worst thing about it, that – and having to realise that these frightful pieces of flesh had once been living, breathing people… if one was too lavish in making one body almost whole, than another one would have sad gaps. There were always odd members which did not seem to fit, and there were always too many legs… It became a grim and ghastly satisfaction when a body was fairly constructed… I think this task dispelled for me the idea that human life is valuable – it could be blown to pieces by blast, just as dust was blown by wind. (40)

Stanley Rothwell hated this aspect of the job: " It takes more than blind courage to face this task and handle these gruesome bundles, it takes guts of an unusual order, or else one has a callous nature that cares for nothing. If you are sensitive you carry the scars for the rest of your life… My old soldiers, seasoned campaigners in battle, worked with tears streaming down their faces. Jock Weir crossed himself and dropped onto his knees to pray; many times I had to excuse myself to go along and vomit after these gruesome jobs." (41)

After a building was hit during a bombing raid the fire service and the Heavy Rescue Squad would arrive. In December 1940, Bernard Regan attended a serious incident on the Isle of Dogs in Poplar. "They had found two more bodies and sent for the Light Rescue to come and take them away, and while I watched two more bodies were uncovered. I know none of us are very happy having to handle corpses, and it shows. They had uncovered two young girls, about eighteen years of age, quite unmarked, they looked as if they were asleep. I looked round at the other men. Most of them were shocked and a bit sick: we usually found bodies mutilated, and we just lifted them out by their hands and feet and quickly got away. Major Brown sees one man being sick, so he fishes out a bottom of rum to be handed round."

Regan then went on to explain his reaction to this difficult situation: "By now I am feeling a bit angry at the prospect of these girls being lugged by their arms and legs, so I got down beside them. They both have only their knickers and short petticoats on, and the dry weather we'd been having, and the rubble packed tight round them had preserved them. Their limbs were not even rigid. They were lifelike: I could not let them be handled like the usual corpses. I know I would have belted the first one that handled them with disrespect, but nobody makes a move to shift them, and they just stand there, gawping... Then I put my right arm under one of the girl's shoulders with her head resting against me, and my left arm under her knees, and carried her up. I laid her on the stretcher, 'You'll be comfortable now my dear.' I did exactly the same thing with the other one. I stood up and waited for some smart Alec to make a snide remark, but nobody did. I cooled down a bit after I had smoked a cigarette. I wonder, why had I been so angry." (42)

Wardens were expected to carry out a whole range of different duties: "At half-past two there was another message from Control. This time it was said that a German parachutist had landed in Lloyd Square, where I lived, and we were to search for him. The police turned out with revolvers and made a ring round the area; everyone seemed to be taking it very seriously, and I searched back-gardens... There was a great deal of 'jitteriness' about parachutists - in London it was rather ludicrous. Since Essex and Surrey offered far greater amenities for landing, and were reasonably handy, it was not likely that anyone would risk all the chimney-pots and roof-tops of London - let alone the trolley-bus wires." (43)

Sometimes members of the ARP were accused of stealing from bombed houses. In May 1941, the Metropolitan Police claimed that out of a sample of 228 men prosecuted for looting, 96 held official positions. One part-time ARP warden in central London claimed that the 130 pairs of ladies' gloves, 214 towels, seventeen bottles of hair lotion, two fur coats and a fur collar he had managed to accumulate were "tips". He was prosecuted because it had been made clear to all members of the Civil Defence were not allowed to accept gifts from grateful victims. (44)

T. P. Peters was an air raid warden in East Grinstead: "On 10 p.m. on Saturday, 26th October, 1940, Stanney in Holtye Road, was demolished. We could hear cries coming from what was left of the house. The most extraordinary thing about this incident was the luck of the three ladies, who were trapped and escaped with minor injuries, but a nurse from Queen Victoria Hospital, who was having a bath at the time, was blown right out with the roof of the house and with the shattered bath. We found her lying on her back, terribly injured, and quite nude. Warden Burnett remarked afterwards: "When I shone my torch on her I thought it was a statue blown over in the garden." We covered her with a coat and she actually asked me what had happened. We got her into the Larches Nursing Home, where Dr. Somerville and his staff did their best, but she died the next day." (45)

Peters faced a more serious problem on 9th July 1943, when the town suffered a very heavy raid. According to the East Grinstead Observer: "Suddenly the roar of a plane approaching the town from the north was heard. It swooped down out of the low-lying clouds and it was then that shoppers and other people realised that the twin-engined bomber was a German. It roared over the town, circled twice and then dropped several bombs. One made a direct hit on a cinema, another on an ironmonger's shop higher up the road, another on a builder's and ladies' outfitters and one fell near a factory. In the cinema was an audience of 184 - the majority being children - who were trapped when the bomb fell." (46)

As a result of the censorship laws, East Grinstead could not be identified as the town hit by the bombing raid: "Death dealing blows were struck at the heart of a quiet South-East town soon after 5 o'clock on Friday, when one of about ten enemy raiders swept in from the coast to cause havoc in the shopping centre, and a large number of casualties among men, women and children. The majority of the casualties were in a cinema, where a bomb scored a direct hit. It was there that the death toll was heavy.... There were many harrowing scenes as children and women were recovered from the debris. A newspaper office was used for a mortuary, and later the bodies were taken to a garage where they were left for identification purposes. Not half of the victims had been identified by Sunday." (47)

Peters himself was one of the survivors of the air raid: "I had just left the back of the Scotch Wool Shop and got to Bridglandʹs when the bombs dropped. I was apparently blown across the road into the building opposite not knowing to this day how I got there or having heard any noise. But my mind soon cleared. I looked around - the sight was almost indescribable. People were lying all round me terribly injured, blown from I do not know where. The extraordinary thing was: How did I escape? Other than a small bump on my head caused by my helmet, I was the only uninjured person present. Bullets were flying round as the raider had returned and was machine-gunning the town... At the Cinema: hardly a body could be seen - all covered by rubble... Our next sad task was at the temporary mortuary (Fosterʹs Garage) where over one hundred bodies were laid out for identification purposes." As a result of the raid 108 people were killed and 235 were seriously injured. It was the largest loss of life in any air raid in Sussex. (48)

Barbara Nixon worked as an ARP warden from May 1940 until the end of the war in 1945. Occasionally, on her day off, she visited her husband who was teaching at the University of Cambridge: "Sunday was my day off, and I went straight from the Post to the station to see if there were any trains running. The upper floors of the station were still burning, and the platforms were covered with the filthy, slimy oil of several fire bombs, but the 4.30 a.m. was just leaving at 7 a.m., and I slept the whole way to Cambridge. By ill-luck, as I left the train, I met a theatrical company on tour, most of whose members I knew. I was very embarrassed, as I was still in my dusty dungarees and my face was smeared and dirty. A large friend of mine, in a pale blue spring outfit with grey furs dangling, said 'Good gracious!' when she recognised me. But when I said that we had a heavy night in London, nobody was interested, and the subject changed to contracts, and how bad poor Peter was in his part. "But, of course, my dear, as you know, he shoudn't ever have gone on the stage - just hasn't got it in him.' I felt like a foreigner... I could still talk the language, just as I can still recite 'Au clair de la lune,' but it did not mean very much." (49)

At the height of the Bitiz there were 127,000 Civil Defence workers. By the end of 1943 the number fell to 70,000. The number of men and women working in the fire service also declined. Those who continued in this work tended to take spare-time war work. By the spring of 1943 there were two hundred stations in London alone where firemen were engaged in productive work and others worked on allotments and farms. Many wardens found similar tasks to occupy them, for example, making toys for orphaned children and collecting money for war savings. (50)

Stanley Rothwell was highly critical of those British politicians that he felt had been responsible for the war. As a ARP warden he hated the job of dealing with the casualties of bombing raids during the early weeks of the Blitz. "Casualties got heavier, we were saturated with blood, dirt and stinking sweat. Our uniforms were now stiffened with clotted blood, we were impregnated with the acrid fumes of cordite and explosives and old brick dust… This is a side of warfare that is unglorious, that someone has to face, a side that is rarely mentioned, a side of war that gets no medals, a side of war that if the bemedaled glory boys who wield the power, if they had to face it, would change their tunes." (51)

George VI announced that "in order that they (Civil Defence workers) should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all weeks of civilian life" for valour on the home front, as there were medals for those at the battlefront. The George Cross was intended to be the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, which was awarded for "acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger". (52)

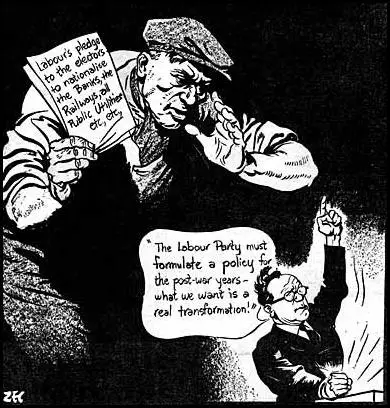

It was claimed that ARP was not run effectively during the war. "The running of a service a thousand strong is a skilled job, and the type of person who goes in for local government is not, as a rule, capable of it… The warden's was the ugly duckling of the services, and suffered the most from bad organization… What, positively could have been done other than what was done? In the first place, a properly functioning Labour Party and a Trades Council, voicing needs and grievances from the wards, or branches, or places of work, criticizing and checking the red tape and ineptitude where these occurred, and, above all, insisting on the treatment of people as people, could have made a great deal of difference… Secondly, a proper democratic organization within the Wardens' Service itself could have rectified many mistakes, as well as developing an atmosphere of willing co-operation, and individual responsibility and initiative, in place of the sour grumbling and ‘browned off' feeling that became only too common." (53)

By the outbreak of the Second World War there were more than 1.5 million people were involved in the various ARP services (later re-named Civil Defence). Full-time ARP staff peaked at just over 131,000 in December 1940 (nearly 20,000 were women). By 1944, with the decreasing threat from enemy bombing, the total of full-time ARP staff had dropped to approximately 67,000 (10,000 of whom were women). During the war almost 7,000 Civil Defence workers were killed. (54)

Emergency Powers Act

On 27th April 1939, Neville Chamberlain made the controversial decision to introduce conscription. In doing so he scrapped a policy, first introduced by Stanley Baldwin in 1936, that Britain would never introduce conscription in peace time and repeated by Chamberlain several times after he became prime minister. It is claimed that Leslie Hore-Belisha, Secretary of State for War, had forced Chamberlain to change his mind. Both members of the Labour Party and the Liberal Party objected to the measure and according to Winston Churchill this was because of "the ancient and deep-rooted prejudice which has always existed in England against Compulsory Military Service." (55)

The Duke of Windsor, the former Edward VIII, made a radio broadcast in Paris condemning this decision. "I speak for no one but myself and without the previous knowledge of any government. I speak simply as a soldier of the last war whose most earnest prayer is that such cruel and destructive madness shall never again overtake mankind. I break my self-imposed silence now only because of the manifest danger that we may all be drawing nearer a repetition of the grim events which happened a quarter of a century ago. You and I know that Peace is a matter far too vital for our happiness to be treated as a political question. We also know that in modern warfare victory will only lie with the powers of evil." (56)

Over 400,000,000 people heard the broadcast and was much discussed in the rest of the world. However, it has remained entirely unknown in Britain as it was banned by the BBC on the orders of Chamberlain. The Duke of Windsor used his contacts in the American broadcasting network and the speech was leaked to journalists all over the world. However, it remained banned in Britain. The way this information was suppressed indicated the way censorship would work during the Second World War. (57)

On 3rd September, 1939, the House of Commons passed the Emergency Powers Act. This enabled the British government to virtually do what it liked with the freedom and property of any citizen simply by issuing the appropriate regulation without reference to Parliament. Censorship was imposed on overseas mail, and telephone trunk lines, though the public did not know this, were tapped. By October, a National Register of all citizens had been completed. Everyone received a buff-coloured identity card with a personal number of six or seven digits. (58)

A few days after the passing of the Emergency Powers Act, a secret internal government was circulated. The unnamed official stated: "The people must feel that they are being told the truth. Distrust breeds fear much more than knowledge of reverses. The all-important thing for publicity to achieve is the conviction that the worst is known… the people should be told that this is a civilians' war, or a People's War, and therefore they are to be taken into the government's confidence as never before…. What is truth? We must adopt a pragmatic definition. It is what it is believed to be the truth. The government would be wise therefore to tell the truth and, if a sufficient emergency arises, to tell one big, thumping lie that will then be believed." (59)

Two days before the outbreak of war, the government established the Ministry of Information. The plans for the ministry had been drawn up by Rex Leeper, the head of the Foreign Office news department. Under this scheme the ministry would be responsible for distributing all information concerning the prosecution of the war and for propaganda at home and abroad. (60) John C. Davidson, the chairman of the Conservative Party, described the plans for wartime propaganda machinery as something "of which any totalitarian state would be proud". (61)

Only a week into the war the new ministry was made to look ridiculous when news leaked through the Paris media that a British Expeditionary Force was on French soil. At first the War Office confirmed the news to journalists. Then it changed its mind and called in the police to confiscate the first editions of the newspapers. This included raiding newspaper offices and stopping trains and pulling over cars driving out of London to stop newspapers reaching the public. When Francis Williams, editor of the Daily Herald, pointed out to the Ministry of Information, that the presence of British troops had been broadcast several times by French radio, and that its censorship policy was not working, its spokesman replied: "The newspapers might have published more details. You can't expect us to not to trust the newspapers." (62)

In the first four weeks of the war the staff of the Ministry of Information, grew from 12 to 999, of which only 43 were journalists. Newspapers complained about this attempt at censorship. The Daily Express said that soon Britain would need leaflet raids on itself to tell its own people how the war was going. Magor-General John Hay Beith, the War Office's director of public relations, took the unusual step of writing to The Times to explain why this policy had been developed and pointed out that the Germans were being so successful on the propaganda front. However, Beith promised improvements. "A large body of correspondents, including a fully representative American contingent... are now with the forces in France." (63)

Dunkirk

A group of fifteen British and nine American journalists were allowed to travel with British troops to Europe. They were looked after by a group of Old Etonian, military officers, who were often drunk. This included the large landowner, Charles Tremayne, who was known to drink neat gin for breakfast and consumed three bottles of it every day. O. D. Gallagher, who worked for The Daily Mail later told Phillip Knightley: "The conducting officers were such astounding caricatures of British army regular officers and upper classes as to be scarcely credible. They were either drunk half the time or half drunk all the time." (64)

Just over 338,200 troops (of whom 150,200 were French) were brought out through Dunkirk, mainly between 26th May and 4th June, and crossed the Channel to Britain in naval ships and in a flotilla of small craft assembled for the occasion. The total casualties of the British Army in France was 68,111. In all, 338,226 men were brought to England from Dunkirk, of whom 139,097 were members of the French Army. Left behind in France were 2,472 guns, 20,000 motorcycles, and almost 65,000 other vehicles. Almost all of the 445 British tanks that had been sent to France with the BEF were abandoned. Six destroyers had been sunk and nineteen damaged. The RAF had also lost 474 aircraft. (65)

General William Ironside, chief of the Imperial General Staff, told Anthony Eden, "This is the end of the British Empire." Churchill appealed to the newspapers not to present it as a major defeat. The Daily Mirror described the operation as "Bloody Marvellous" and the Sunday Dispatch suggested that divine intervention had been responsible. It pointed out that Dunkirk had followed a nation-wide service of prayer and that during the evacuation "the English Channel, that notoriously rough stretch of water which has brought distress to so many holiday-makers in happier times, became as calm and smooth as a pond... and while the smooth sea was aiding our ships, a fog was shielding our troops from devastating attack by the enemy's air strength." (66)

The New York Times went along with this message: "So long as the English tongue survives, the word Dunkirk will be spoken with reverence. For in that harbour, in such a hell as never blazed on earth before, at the end of a last battle, the rags and blemishes that have hidden the soul of democracy fell away. There, beaten but unconquered, in shining splendor, she faced the enemy." (67)

Edward Murrow, of CBS, the radio station, was the only dissenting voice when he claimed that "there is a tendency to call the withdrawal a victory." (68) However, this was something only available to an American audience. Phillip Knightley, the author of The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982), has pointed out that "it was not until the late 1950s and early 1960's - nearly twenty years after the event - that a fuller, truer picture of Dunkirk began to emerge." (69)

Ministry of Information

Soon after Winston Churchill became prime minister he appointed Lord Beaverbrook, the press baron, as Minister of Air Production. However, his other role was to control what the press had to say about the government. Some of Churchill's ministers, including Clement Attlee, who loathed Beaverbrook with a "rare intensity for such a calm man". However, it was an inspired choice and as Lieutenant General Ian Jacob pointed out: "Beaverbrook as minister of aircraft production is still Beaverbrook the press king." (70)

Duff Cooper became the new Minister of Information. Cooper had been one of the main figures in the downfall of Neville Chamberlain when he resigned from the government over appeasement. Churchill took a keen interest in what the newspapers said about him and Robert Barrington-Ward, the editor of The Times described him as having the press "rather on the brain". (17) Churchill would often get very upset with what appeared about him but was less interested in other issues. Cooper was upset by Churchill's lack of support and Michael Balfour, who worked in the Ministry of Information, quoted him as saying: "When I appealed for support from the PM, I seldom got it. He was not interested in the subject. He knew that propaganda was not going to win the war." (72)

People soon became aware that the government was keeping information from them. The Nazi government took advantage of this situation and William Joyce (Lord Haw Haw) provided an alternative news source on the war. Joyce's broadcasts came from studios in Berlin and relayed over a network of German-controlled radio stations that included Hamburg, Bremen, Luxembourg, Hilversum, Calais, Oslo, and Zeesen. The German Büro Concordia organisation, which ran several black propaganda stations, many of which pretended to broadcast illegally from within Britain. At the height of his influence, in 1940, Joyce had an estimated six million regular and 18 million occasional listeners in the United Kingdom. (73)

These broadcasts encouraged the spreading of rumours that undermined the war effort. Early in the war a schoolmaster was jailed for advancing "defeatist" theories to his pupils. Attempts were made to stop the spreading of stories that would damage the war effort.. An Emergency Regulation in June 1940, made it an offence to circulate "any report or statement" about the war which was "likely to cause alarm or despondency". Fines up to fifty pounds could be imposed if you were found guilty of the offence. (74)

The government was highly successful in providing false information on the Battle of Britain: As A. J. P. Taylor, the author of English History: 1914-1945 (1965) pointed out that the pilots helped them in this: "Pilots on both sides naturally exaggerated their claims in the heat of combat. The British claimed to have destroyed 2,698 German aeroplanes during the battle of Britain and actually destroyed 1,733. The RAF lost 915 aeroplanes. Fighter command had 656 aeroplanes on 10 July, and 655 on 25 September." (75)

During the Blitz the Daily Worker, the newspaper of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was highly critical of the government, especially over its poor performance over the provision of public shelters. It commented: "The shelter policy of the government is not just a history of incompetence and neglect, it is a calculated class policy... A determination not to provide protection because profit is placed before human lives... the bankruptcy of the government's shelter policy is plain for all to see... safe in their own luxury shelters the ruling class must be forced to give way." (76)

American journalists were also critical of the government over this issue. Edward Murrow, of CBS, told the Americans that the old Britain was dying and that ordinary people were asking awkward questions: "Why must there be 800,000 unemployed when we need shelters? Why are new buildings being constructed when the need is that the wreckage of bombed buildings be removed from the streets? What shall we do with victory when it is won? (77) Drew Middleton , another American journalist, also complained about the way the British government controlled the newspapers: "We became aware of the enormous propaganda machine pumping out the government view." (78)

Daily Mirror & Sunday Pictorial

been a strong supporter of Winston Churchill in his campaign against appeasement but was disappointed by his actions once he became prime minister. In an article on 6th October, 1940, Cudlipp praised the appointment of Labour ministers but felt that there were too many elderly members of the Conservative Party in the government: "Party politics of the worst type has been the basis of this Cabinet reconstruction. Failures and mediocrities have been retained because they are Conservatives: competent men have been ignored because they are not eminent in the political Party game." (79)

The following day Churchill held a War Cabinet meeting where he raised the issue of Cudlipp's article and others being published in the left-wing press. Churchill claimed: "The immediate purpose of these articles seemed to be to affect the discipline of the Army, to attempt to shake the stability of the government, and to make trouble between the government and organised labour. In his considered judgment there was far more behind these articles than disgruntlement or frayed nerves. They stood for something most dangerous and sinister, namely, an attempt to bring about a situation in which the country would be ready for a surrender peace." (80)

Churchill asked who owned these newspapers. Sir John Anderson replied: "The Daily Mirror and the Sunday Pictorial were owned by a combine. A large number of shares were held by bank nominees, and it had been possible to establish which individual, if any, exercised the controlling financial interest of the newspaper. It was believed, however, that Mr I. Sieff (Israel Sieff, English businessman and Zionist and later chairman of the British retailer Marks & Spencer) had a large interest in the paper, and that Mr Cecil Harmsworth King (Cecil King, director of both newspapers) was influential in the conduct of the paper." Anderson went on to argue that "it would be wrong to attempt to stop publication of these articles by a criminal prosecution in the Courts." (81)

As Wilfrid Roberts, the Liberal Party MP pointed out: "The Daily Mirror belonged originally to Lord Rothermere. About ten years ago, Lord Rothermere sold his shares, gradually, on the Stock Exchange. They were brought up in small blocks. There is no big, or controlling, group of shares now held by one person. The shares held by nominees represent only between five and ten per cent of the whole shareholding of the paper. In other words, this paper, unlike many others, is run by a board of directors and a chairman. The Daily Mirror has not changed (its policy) in the last five or six years. Its staff has not changed, since the time when the Prime Minister wrote for it." (82)

Clement Attlee offered to speak to H. G. Bartholomew and Cecil King, two of the senior figures at the newspaper group. They met on 12th October, 1940, in an air raid shelter used by government ministers. King recorded in his diary that Attlee told them that the government believed that the newspapers showed a subversive influence which might endanger the nation's war effort. "I asked him to give an example. He said he couldn't think of one... Attlee was critical but so vague and evasive as to be quite meaningless. We got the impression that the fuss was really Churchill's, that Attlee had been turned on to do something he was not really interested in, and had not bothered to read his brief." (83)

Cudlipp upset many people in the Conservative Party with his attacks on the government, and in December, 1940, Quintin Hogg, asked in the House of Commons "Why Mr. Hugh Cudlipp, aged about twenty-seven years and editor of the Sunday Pictorial, had not been called up for military service." (84) Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour in Churchill's government replied: "The calling up of Mr Cudlipp was deferred on the application of his employers, supported by the Ministry of Information. I understand that this deferment was against the strong desire of Mr Cudlipp himself and, as a result, his employers later withdrew the request for deferment. Arrangements are accordingly being made to post Mr Cudlipp to the Armed Forces." (85)

In an editorial the newspaper accused Westminster politicians of "letting the people down" and concluding that Winston Churchill ought to pack off many of them, including half of his ministers, "for a permanent rest-cure". (86) Churchill immediately demanded that the Home Secretary should suppress the offending newspaper. If the article did not breach existing defence regulations, a new regulation should be introduced. Morrison disagreed and argued that "the democratic principle of freedom for expression of opinion meant taking the risk that harmful opinions may be propagated." (87)

Daily Worker Banned

The Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, was growing increasing concerned by the behaviour of the Daily Worker. He was especially worried about its call for a negotiated peace with Adolf Hitler. Later that year the CPGB sponsored and the Daily Worker advertised a series of "People's Conventions" to promote a negotiated peace. Any government wanting to maintain national morale and unity in the darkest days of the Blitz was bound to be disturbed. He therefore decided to use regulation 2D of the Emergency Powers Act ("to systematic publication of matter calculated to foment opposition to the prosecution of the war to a successful issue") and decided to close the newspaper. (88)

On 21st January, 1941, the police took over the newspaper's offices in London and Glasgow. Morrison also took the same action against the journal, The Week, edited by Claud Cockburn. The Labour Party voted overwhelmingly to endorse Morrison's decision. However, in the House of Commons, the left-wing MP, Anueurin Bevan, moved a motion of qualified protest because the newspaper had not been allowed to state its case, and he received the support of half a dozen colleagues. (89)

Morrison justified his decision in An Autobiography published after the war: "The suppression of the Daily Worker was not of course, an attack on freedom... the slavish obedience to the Moscow line was a negation of freedom... the slavish obedience to the Moscow line was a negation of freedom of the printed word. There was evidence that the paper was fomenting unofficial strikes and disputes. The articles in it were insidious enough to cause direct damage to the war effort... Not unexpectedly there was no protest from Russia about the closing down of the Daily Worker. The Soviet Union always admires bold and firm action." (90)

Lord Beaverbrook Plot

Winston Churchill had appointed Lord Beaverbrook as Minister of Aircraft Production in order to guarantee him the support of the Daily Express and the Evening Standard for his government. The two men had disagreed about appeasement but the two men had worked together in the First World War and was aware of his "power to inspire and drive, his ability to get to the heart of a problem at speed, his refusal to despair or admit defeat." Churchill commented: "I needed his vital and vibrant energy." (91)

However, in 1942, Beaverbrook began to plot behind Churchill's back to create a new government controlled by the press lords. As Lance Price pointed out: "No press baron before or since has enjoyed so much real political power as Lord Beaverbrook but still it was not enough... Only in Beaverbrook's wildest dreams could he ever have become prime minister. He was on the way out not up." (92)

On 13th February, 1942, the Daily Mail ran a "violently anti-Churchill, anti-government leader" that had caused fury in Downing Street. Sir Henry Channon, a junior minister in the government, heard talk that Beaverbrook, was planning to overthrow Churchill and put himself at the head of the government. (93) Churchill's wife complained about Beaverbrooks "intrigue and treachery" and suggested "ridding yourself of this microbe" and after his sacking you will "see if the air is not clearer". (94)

Churchill decided to turn to Labour Party ministers for support. He did this by appointing Clement Attlee as Deputy leader of the government and Richard Stafford Cripps as leader of the House of Commons. Beaverbrook vigorously opposed the decision. Churchill now removed Beaverbook from the War Cabinet but still remained in office. Beaverbrook found this unacceptable and resigned from the government on 26th February. Attlee, who had won the power struggle with Beaverbrook, later stated that he "was the only evil man I ever met." (95)

Archibald Rowlands, the Permanent Secretary to the Ministry of Air Production, was a very close friend of Lord Beaverbrook. He later explained why Beaverbrook left the government: "The real reason for refusing to stay in the War Cabinet was that he judged that the present administration was losing ground in public esteem and was likely to be short-lived - and he did not want to be associated with its collapse." (96)

Philip Zec Cartoon

Soon after the outbreak of the Second World War, the Daily Mirror recruited Philip Zec as a cartoonist. Zec's cartoons were an immediate success with the readers. Zec, who was Jewish, felt passionately about the need to defeat Hitler, produced a series of powerful cartoons on the war. As his brother, Donald Zec, pointed out: "He presented Hitler, Goering, and others in the Nazi hierarchy as strutting buffoons. Replacing ridicule with venom, he often drew them in the form of snakes, vultures, toads, or monkeys. Not surprisingly, captured German documents listed Zec's name among those to be arrested immediately England had fallen." (97)

Zec sometimes upset the British government with his cartoons. On 5th March, 1942, the Daily Mirror published a cartoon on the government's decision to increase the price of petrol. The cartoon showed a torpedoed sailor with an oil-smeared face lying on a raft. The journalist, William Connor, provided the caption: "The price of petrol has been increased by one penny. Official." As Angus Calder pointed out: "While many readers seem to have accepted this at its face value as an injunction that they should not complain about shortages and rising prices at such a time as this, Morrison took it to mean that seamen were risking their lives for profiteers at home. Ernest Bevin agreed with him, and Churchill wanted instant suppression of the paper." (98)

Philip Zec, The Daily Mirror (5th March, 1942)

The same issue carried an editorial which mocked the army's leaders as "brass buttoned, boneheads, socially prejudiced, arrogant and fussy with a tendency to heart disease, apoplexy, diabetes and high blood-pressure." (99) Winston Churchill believed that the cartoon suggested that the sailor's life had been put at stake to enhance the profits of the petrol companies. "It was, he declared, bound to have a strong effect in deterring seamen from agreeing to serve on oil tankers. The leading article he regarded as a gross and improper libel on the higher officers in the army, and incidentally on the government which appointed them, and one calculated to spread alarm and despair in the ranks and make men unwilling to fight in the belief that they were being led to their deaths by aged and stupid incompetents." (100)

In the House of Commons, Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary, called it a "wicked cartoon" and Ernest Bevin, the Minister of Labour, argued that Zec's work was lowering the morale of the armed forces and the general public. By 18th March, 1942, the Law Officers advised Morrison that the cartoon and articles published by the newspaper were infringements of regulation 2D. However, Morrison decided against this after one of his advisers claimed that the newspaper's "criticisms simply reflected real and widespread disenchantment with the government and that it would be very imprudent to hit out at the mouth-piece for genuine popular feeling." (101)

Churchill arranged for MI5 to investigate Zec's background, and although they reported back that he held left-wing opinions, there was no evidence of him being involved in subversive activities. H. G. Bartholomew and Cecil Thomas were ordered to appear before Morrison at the Home Office. Zec's cartoon was described as "worthy of Goebbels at his best" and turning on Thomas, Morrison told him that "only a very unpatriotic editor could pass it for publication". Morrison informed Bartholomew that "only a fool or someone with a diseased mind could be responsible" for allowing the Daily Mirror to publish such material. (102)

When Anueurin Bevan heard that the government was considering closing down the Daily Mirror he forced a debate on the issue in the House of Commons. Some MPs were appalled when Herbert Morrison suggested that the newspaper might be part of a fascist plot to undermine the British Government. Several pointed out that the Daily Mirror had been campaigning against fascism in Europe since the early 1930s. In doing so, it had supported Churchill and Morrison in their struggle against appeasement, the foreign policy of Neville Chamberlains government. (103)

Bevan argued in the debate that: "I do not like the Daily Mirror and I have never liked it. I do not see it very often. I do not like that form of journalism. I do not like the strip-tease artists. If the Daily Mirror depended upon my purchasing it, it would never be sold. But the Daily Mirror has not been warned because people do not like that kind of journalism. It is not because the Home Secretary is aesthetically repelled by it that he warns it... He (Morrison) is the wrong man to be Home Secretary. He has for many years the witch-finder of the Labour Party. He has been the smeller-out of evil spirits in the Labour Party for years. He built up his reputation by selecting people in the Labour Party for expulsion and suppression. He is not a man to be entrusted with these powers because, however suave his utterance, his spirit is really intolerant. I say with all seriousness and earnestness that I am deeply ashamed that a member of the Labour Party should be an instrument of this sort of thing. How can we call on the people of this country and speak about liberty if the Government are doing all they can to undermine it? The Government are seeking to suppress their critics. The only way for the Government to meet their critics is to redress the wrongs from which the people are suffering and to put their policy right." (104)

The majority of MPs were firmly behind Morrison and therefore no vote was taken over the issue. The press, understandably, was least happy with him. The Times, Manchester Guardian, News Chronicle and the Daily Herald objected to the way he had threatened to use defence regulation 2D against government critics. The National Council for Civil Liberties also expressed grave concern and organized a mass protest meeting in London in April. It has been argued that "it was not a happy experience for Morrison, to be pilloried as an enemy of civil liberties when he had fought so long behind the scenes to protect the freedom of the press." (105)

Hugh Cudlipp later record his pleasure when the examination of secret files after the war to see how the actions of the Daily Mirror and the Sunday Pictorial were seen in Nazi Germany. "Philip Zec was a Socialist, and therefore passionately anti-Nazi. He was also a Jew, and passionately anti-Hitler. Helping the enemy? When the German High Command papers, or such as were available, were examined by the Allies after the war, a document was disclosed which reduced to fatuity the view of the British War Cabinet about the Mirror and Pictorial at the end of 1940, the beginning of 1941, and the spring of 1942. The document was an order that all Mirror directors were to be immediately arrested when London was occupied." (106)

Politicians and the Press

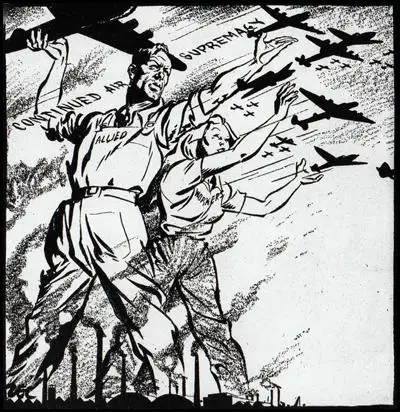

After Adolf Hitler ordered the invasion of the Soviet Union, members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) suddenly became enthusiastic supporters of the national war effort and agitation began to permit the Daily Worker newspaper to publish again. Morrison at first resisted, but in August 1942 after pressure at the Labour Party annual conference and the National Executive Council, and with the prospect of censure at the coming Trade Union Congress, he submitted and lifted the ban. (107)

The Daily Mirror continued to criticise the government when its reporters discovered examples of incompetence. Its postbag showed overwhelming support for its campaigning style. Its cartoons, especially, those produced by Philip Zec, concentrated on portraying British civilians, rather than the politicians, as the real heroes and heroines of the war. A cartoon published on 15th July, 1943, reflected this point of view. Christopher Tiffney has pointed out: "While the glory inevitably went to the pilots and aircrew who risked their lives daily against the Luftwaffe and enemy anti-aircraft gunners, the aircraft which they flew and the bombs which they dropped had to be produced in vast quantities under very difficult conditions. The efforts of the men and women who kept the production lines rolling despite the devastating bombing on Britain's manufacturing centres such as Coventry, Bristol and Birmingham, coupled with the privations inflicted by the war on food, fuel and clothing, were nothing short of heroic." (108)

Winston Churchill had a terrible fear that this criticism would have an impact on his popularity and asked Ernest Bevin to put pressure on The Daily Herald to provide support. As the Liberal Party had also joined the coalition and they were asked to work on their friends in the media. Every morning Churchill would read all the daily newspapers. The Daily Telegraph was Churchill's most loyal defender and the prime minister told Robert Barrington-Ward, the editor of The Times, that he read "the papers every morning, The Times, last but one," finishing with the "Telegraph, because I knew that it will be all right!" (109)

BBC and Propaganda

The BBC had a monopoly of authorized radio broadcasting in Britain. As Angus Calder has pointed out: "The BBC monopoly make it easy to ensure that only 'safe' people were heard on the air, the use of pre-recording made assurance doubly sure. Scripts of live programmes were vetted by the censors in advance. When live talks were delivered, the announcer would sit in the studio, carefully comparing what the speaker said with the censored script in front of him, with a special switch to hand by which he could cut the speaker off instantly if he stayed. A similar device was used for essentially spontaneous programmes like the Brains Trust; it had the disadvantage that if a trusted performer had suddenly gone berserk and shouted 'Peace at any price!' or 'The Germans are here!', the damage would have been done before the switch could be used. But there were few security leaks in unscripted discussions." (110)

The Government, without taking over the BBC directly, reserved the right to order the BBC to broadcast anything it wanted to be heard. It was also the first war in which it was technically possible for one combatant power to relay its propaganda directly into the homes of the citizens of another. Every twenty-four hours, the Political Warfare Executive broadcast a 160,000 words over the air in 23 languages and nearly a quarter of this went to Germany itself. This propaganda was very successful because of the BBC's reputation for objectivity. (111)

George Orwell worked for the BBC during the Second World War. Between 1941 and 1943 he was a Talks Producer in the Empire Department. This mainly involved producing cultural programmes for intellectuals in India and South-East Asia. According to his biographer, Bernard Crick, it was "essential war work, of a kind, close to propaganda". He arranged for Dylan Thomas and T. S. Eliot to read their poems and E. M. Forster to give a talk on his novels. (112) However, the BBC did stop him from allowing Mulk Raj Anand from giving a talk on the Spanish Civil War. They also complained after Kingsley Martin spoke on the subject of education, because they considered it to be a "left-wing view". (113)

Other contributors included Stephen Spender, Herbert Read, George Woodcock and Cyril Connolly. Orwell felt guilty about his involvement in propaganda. Woodcock later wrote: "In a discussion I had with him at the time he defended his activities by contending that the right kind of man could at least make propaganda a little cleaner than it would otherwise have been, and I know he managed to introduce one or two astonishing items into his broadcasts, but he soon found there was in fact little he could do, and he left the BBC in disgust." (114) Woodcock complained to Orwell that "Even if the broadcasts were intended by him to keep the Fascists out of India, they were also intended by the system to keep India in the clutches of the British nabobs." (115) Michael Shelden claims that Orwell used his experiences at the BBC when he was writing Nineteen Eighty-Four after the war. (116)

Newspapers and the Second World War

In the 1930s the British were well known to be the world's most avid newspaper readers. In 1943, the number of newspapers brought per head of the population was even higher than before the war. It was estimated by the Wartime Social Survey that four men out of five and two women out of three saw a newspaper on any one day. As a result of the shortage of paper, the size of the newspaper, had to be reduced. The typical daily was reduced from between 16-24 to six pages. The "quality" newspapers like The Times and The Telegraph and the Manchester Guardian, were allowed eight pages. (117)

The Manchester Guardian explained its policy during the war: "Rather than produce many editions with few pages, the Manchester Guardian produced fewer editions with as many pages as it could. This meant the paper shrank in size from an average of 16 to between six to eight pages. Although the reduced size meant the paper had less space for advertising, revenue was compensated by increased sales. By 1941 circulation was 60,000, an increase of 10,000 from 1939.... As many Manchester Guardians were sold as could be printed. Subscribers also no longer received a discount - some had been given in the 1930s as part of a readership drive. Despite the reduction in pages, the price remained the same – two pence." (118)

By the end of 1943, well over a third of the nation's nine thousand journalists were in the forces, and a substantial proportion of the rest were engaged on on journalistic work. Most newspapers lost about three-quarters of their staff photographers, and even without the activities of the censorship in this field, they would have been compelled to use more or less identical photographs as only official service photographers were allowed to work in overseas theatres of war. Eventually, journalists were allowed to report from the front-line. Around fifty journalists from Britain and the British Empire were killed or wounded in action during the war. (119)

Several journalists increased their reputation as talented writers during the war. This included Ernie Pyle, Martha Gellhorn, Marguerite Higgins and Alan Moorehead, However, Charles Lynch, a journalist who had been accredited to the British army for the Reuters News Agency, was much more critical of the role that journalists played in the war: "It's humiliating to look back at what we wrote during the war. It was crap - and I don't exclude the Ernie Pyles or the Alan Mooreheads. We were a propaganda arm of our governments. At the start the censors enforced that, but by the end we were our own censors. We were cheerleaders. I suppose there wasn't an alternative at the time. It was total war. But, for God's sake, let's not glorify our role. It wasn't good journalism. It wasn't journalism at all." (120)

References

(1) Martin Gilbert, The Second World War (1989) page 118

(2) W. R. Matthews, Saint Paul's Cathedral in Wartime 1939-1945 (1946) pages 36-37

(3) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) page 104

(4) Vere Hodgson, Few Eggs and No Oranges (1976) page 147

(5) Philip Ziegler, London at War: 1939-1945 (1995) page 99

(6) The Aberdeen Press and Journal (21st December 1940)

(7) King George VI, speech (23rd September 1940)

(8) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) pages 256-257

(9) Christopher Wren, quoted by M. J. Jappy, in Danger UXB (2001) pages 92-93

(10) Tony White, quoted by Felicity Goodall, in a A Question of Conscience (1997) page 130

(11) Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004) pages 342-343

(12) The Liverpool Echo (2nd July, 1955)

(13) Danny Buckland, The Daily Mirror (21st October, 2015)

(14) James Owen, The Daily Telegraph (24th June 2010)

(15) Richard Tunbridge, The Tunbridge Family in the Second World War (May, 2019)

(16) Kerin Freeman, The Civilian Bomb Disposing Earl: Jack Howard and Civilian Bomb Disposal in WW2 (2014) page 200

(17) The Liverpool Echo (2nd July, 1955)

(18) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) page 104

(19) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 22

(20) Philip Ziegler, London at War: 1939-1945 (1995) page 29

(21) The Slough Observer (22nd September 1939)

(22) Manchester City News (23rd September 1939)

(23) John Langdon-Davies, Lilliput Magazine (July, 1939)

(24) Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004) page 384

(25) Penny Starns, Blitz Families (2012) page 13

(26) John Anderson, The Protection of Your Home Against Air Raids (1940)

(27) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) pages 54-57

(28) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 22

(29) Winston Churchill, letter to Neville Chamberlain (1st October, 1939)

(30) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) pages 8-9

(31) Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004) page 385

(32) Frances Faviell, A Chelsea Concerto (1959) page 115

(33) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) page 322

(34) Gavin Mortimer, The Longest Night: Voices from the London Blitz (2006)

(35) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) page 74

(36) Juliet Gardiner, Wartime: Britain 1939-1945 (2004) page 386

(37) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 196

(38) Stanley Rothwell, Lambeth at War (1981) page 8

(39) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) page 26

(40) Frances Faviell, A Chelsea Concerto (1959) page 115

(41) Stanley Rothwell, Lambeth at War (1981) page 17

(42) Bernard Regan, Imperial War Museum Department of Documents (88/10/1) pages 29-30

(43) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) pages 34-35

(44) Juliet Gardiner, The Blitz (2010) page 328

(45) T. P. Peters, Reminiscences (1945) page 2

(46) East Grinstead Observer (17th July, 1943)

(47) East Grinstead Courier (16th July, 1943)

(48) T. P. Peters, Reminiscences (1945) pages 5-6

(49) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) page 124

(50) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) pages 339-340

(51) Stanley Rothwell, Lambeth at War (1981) page 17

(52) King George VI, speech (23rd September 1940)

(53) Barbara M. Nixon, Raiders Overhead (1943) pages 159-169

(54) BBC Report: Air Raid Precautions (September 2005)

(55) Winston Churchill, Gathering Storm (1948) page 276

(56) Duke of Windsor, speech in Paris (8th May, 1939)

(57) W. J. West, Truth Betrayed (1987) page 161

(58) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 166

(59) Secret internal government memo entitled The Preservation of Civilian Morale (September, 1939)

(60) Lance Price, Where Power Lies: Prime Ministers v the Media (2010) page 109

(61) John C. Davidson, Memoirs of a Conservative (1970) page 425

(62) Francis Williams, A Prime Minister Remembers (1961) page 5

(63) Magor-General John Hay Beith, The Times (24th October, 1939)

(64) Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982) page 206

(65) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) pages 592

(66) The Sunday Dispatch (2nd June, 1940)

(67) The New York Times (1st June, 1940)

(68) Edward Murrow, CBS broadcast (2nd June, 1940)

(69) Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty: The War Correspondent as Hero, Propagandist and Myth Maker (1982) page 216

(70) Lance Price, Where Power Lies: Prime Ministers v the Media (2010) page 115

(71) Donald McLachlan, In the Chair: Barrington-Ward of The Times (1971) page 194

(72) Michael Balfour, Propaganda in War: 1939-1945 (1979) page 64

(73) Richard Lucas, World War Magazine (February, 2010)

(74) Angus Calder, The People's War (1969) page 134

(75) A. J. P. Taylor, English History: 1914-1945 (1965) page 608

(76) The Daily Worker (7th September, 1940)

(77) Edward Murrow, CBS broadcast (1st October, 1940)

(78) Drew Middleton, letter to Phillip Knightley (1st November, 1972)

(79) Hugh Cudlipp, Sunday Pictorial (6th October, 1940)

(80) Winston Churchill, Cabinet minutes (7th October, 1940)

(81) Sir John Anderson, Cabinet minutes (7th October, 1940)

(82) Wilfrid Roberts, House of Commons (26th March, 1942)

(83) Cecil King, diary entry (12th October, 1940)

(84) Quintin Hogg, House of Commons (4th December, 1940)

(85) Ernest Bevin, House of Commons (4th December, 1940)

(86) The Sunday Pictorial (26th October 1941)

(87) Herbert Morrison, cabinet meeting 17th November 1941)