Public Air-Raid Shelters

Before the war started the government made money available for materials for local authorities to build public outdoor shelters, although they had to foot the bill for the construction costs. New buildings had to incorporate spaces for shelters, and employers with a workforce of fifty or more in a designated target area were obliged to provide shelter accommodation for their employees (they would receive government funding to help pay for this). Once war started the government urged local authorities to provide purpose-built public shelters, above ground heavily protected brick and concrete constructions capable of holding up to fifty people. Progress was slow and by the time of the Blitz of the 27.5 million people living in areas likely to be attacked, only 17.5 million had been provided with some sort of shelter, domestic or public. (1)

Barbara Nixon, an air-raid warden in London later wrote: "It is now generally admitted that during September 1940 the shelter conditions were appalling. In many boroughs there were only flimsy surface shelters, with no light, no seats, no lavatories, and insufficient numbers even of these; or railway arches and basements that gave an impression of safety, but had only a few inches of brick overhead, or were rotten shells of buildings with thin roofs and floors... In our borough... we had two capacious shelters under business firms, which held three or four hundred, also fifteen small sub-surface concrete ones in which fifty people could sit upright on narrow wooden benches along the wall. But they were poorly ventilated, and only two out of the nine that came in my province could pretend to be dry." (2)

Many people sheltered under railway arches. One of the most popular was Tilbury railway arch in Stepney. The borough council made it into a public shelter for 3,000 people. However, it is claimed that as many as 16,000 used it on some nights. It was visited by many journalists and Negley Farson found its "vital, impulsive life... inspiring". (3) Harold Scott agreed and described how "a girl in a scarlet cloak danced wildly to the cheers of an enthusiastic audience; a party of Negro sailors sang spirituals while someone played the accordion." (4)

Another popular shelter was the Spitalfield Shelter in Stepney. The London Fruit & Wool Exchange was opposite Christ Church in Spitalfields. Built in 1929, as well as having a grand wood-panelled auction room seating 900, it had a maze of basement tunnels that could be used as an underground shelter. (5)

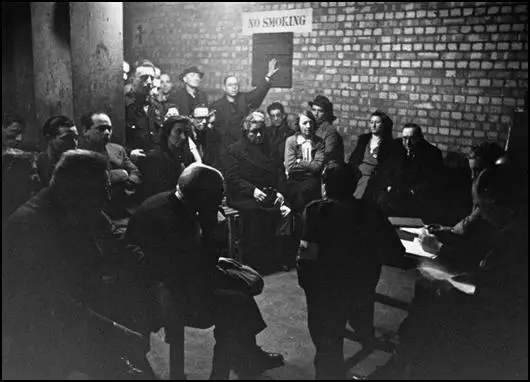

Mickey Davies was an optician but on 13th September, 1940, his business was destroyed by a bomb. Mickey, with time on his hands, decided he would organize the Spitalfield Shelter. Although designed for 2,500 people, some days over 5,000 crammed into the shelter. "The heat of the cellar", Davies wrote, "became literally hardly bearable. A steady stream of semi-conscious or unconscious people was passed towards the doorway." It was a chaotic situation and Davies inspired his fellow shelterers to create their own order. A shelter committee was democratically elected and Davies became chief shelter marshal. (6)

As Steve Hunnisett has pointed out: "To begin with, conditions were appalling, with almost non-existent sanitation, no proper bedding (people initially slept upon bags of rubbish) and minimal lighting. The floors soon became awash with urine, faeces and other filth. Mickey Davies was appalled by what he found and by the apparent lack of interest, or at best, will from the authorities to get things better organised. Davies was highly intelligent and more importantly, a superb organiser and he quickly became invaluable to the shelterers and a thorn in the side of the local authority in his efforts to improve the conditions for those using the shelter." (7)

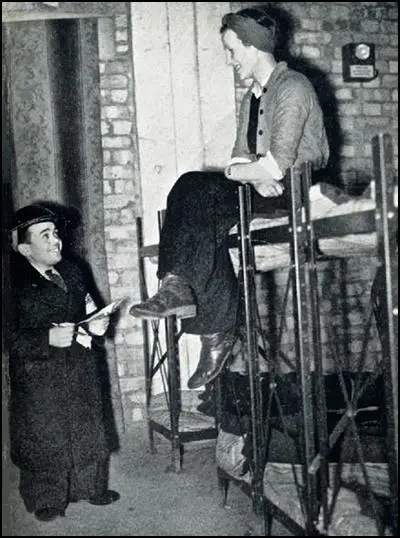

Mickey Davies only 4 feet 6 inches tall and became known as "Mickey Midget". (8) The Daily Mirror reported: "In charge of one of London's biggest shelters is a dwarf - a little man who has performed wonders during the air raids and whose judgement is never questioned by any of the 2,000 shelterers whose safety is under his supervision." (9) Joseph Westwood, Under-Secretary of State for Scotland, was very impressed when he Mickey and told an audience in Edinburgh: "I wish you could have met Mickey. He is a dwarf. But in mind and spirit he is a giant. He is lord of one of the biggest shelters in London. Two thousand shelterers elected him chief shelter marshal." (10)

J. B. Priestley wrote about people like Mickey Davies who emerged as leaders during the Second World War: "It so happens that this war, whether those at present in authority like it or not, has to be fought as a citizen's war... They are a new type, what might be called the organized militant citizen. And the whole circumstances of their war-time favour of a sharply democratic outlook. Men and women with a gift for leadership now turn up in unexpected places. The new ordeals blast away the old shams. Britain, which in the years immediately before this war was rapidly losing such democratic virtues as it possessed, is now being bombed and burned into democracy." (11)

There is evidence that members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) were involved in organising people in air-raid shelters. Euan Wallace, a Conservative Party cabinet minister, wrote: "There is little doubt that the Daily Worker and the Communist Party are taking the opportunity of creating trouble." (12) Ritchie Calder argued in his book, Carry on London (1941) that "Mickey's form of common sense community socialism" was seen by some as "Communism". When told that there were "Communists" amongst the Shelter Committee, he replied that "There may be bigamists amongst them for all I care!" (13)

The poor sanitation in Mickey's Shelter increased the risk of disease and infection. "Mickey set up first aid and medical units, and raise money to equip a dispensary. He even persuaded stretcher bearers and others to come in on their off duty times to minister to the sick and injured." (14) Davis also persuaded Marks and Spencers to install a canteen. When the leading American politician, Wendell Willkie, visited London during the Blitz, he was taken to "Mickey's Shelter as a showplace of British democracy." (15) His daughter has pointed out that his shelter was "visited by people from American ex-Presidents to Clementine Churchill (all signed his visitors' book)." (16)

In early 1941 local councils were authorised to provide waterborne sanitation in large shelters, including chemical toilets. Changes were made to those underground stations that were closed to trains. The walls were whitewashed, the lighting improved, the track was boarded over and 200 three-tier bunks were installed, improved lavatory facilities replaced the original buckets, and a system of tickets was introduced to provide a bunk or reserved floor space for regular shelterers. Westminster Library donated 2,000 books and educational lectures were arranged to take place on the underground platforms. (17)

In February, 1941, it was announced that public shelters were available for 1,400,000 people in the London region, and domestic shelters for 4,500,000. This still left about one Londoner in five "unprotected". In March 1941 it was decided that all the brick surface shelters made without cement should be demolished at Government expense. By the autumn of that year, most of the dampness in the remaining shelters had been countered. (18)

Primary Sources

(1) Barbara Castle, Fighting All The Way (1993)

What we also lacked was an adequate shelter policy, and I had been agitating together with our left-wing group on the Council for the deep shelters which Professor J. B. S. Haldane had been advocating. Haldane, a communist sympathizer and eminent scientist, had studied at first hand the effects of air raids on the civilian population during the Spanish Civil War and had reached conclusions on the best way to protect them, which he had embodied in a book ARP published in 1938. In it he argued that high explosive, not gas, would be the main threat. He pointed out that modern high explosives often had a delayed-action fuse and might penetrate several floors of a building before bursting and that therefore basements could be the worst place to shelter in. He stressed the deep psychological need of humans caught in bombardment to go underground and urged the building of a network of deep tunnels under London to meet this need and give real protection.

The government did not want to know. In 1939 Sir John Anderson, dismissing deep shelters as impractical, insisted that blast - and splinter-proof protection was all that was needed and promised a vast extension of the steel shelters which took his name. These consisted of enlarged holes in the ground covered by a vault of thin steel. They had, of course, no lighting, no heating and no lavatories. People had to survive a winter night's bombardment in them as best they could. In fact, when the Blitz came, the people of London created their own deep shelters: the London Underground. Night after night, just before the sirens sounded, thousands trooped down in orderly fashion into the nearest Underground station, taking their bedding with them, flasks of hot tea, snacks, radios, packs of cards and magazines. People soon got their regular places and set up little troglodyte communities where they could relax. I joined them one night to see what it was like. It was not a way of life I wanted for myself but I could see what an important safety-valve it was. Without it, London life could not have carried on in the way it did.

(2) Robert Boothby, Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel (1978)

Then came the Blitz.... Every night, from dusk to dawn the German bombs fell upon them. Woolton suggested that I might go down there every morning about six o'clock when the 'All-clear' sounded, and see what I could do to help. I found that, as they came out of the shelters, what comforted them most was a kiss and a cup of tea. These were easily provided. Almost overnight I got the Ministry of Food to set up canteens all over the East End, manned by voluntary workers, where the tea was free. When we took them back to their homes, often reduced to rubble, their chief concern was what had happened to the cat. I am afraid that the cat searches which I tried to organize were less successful than the canteens.

A number of people, including Kingsley Martin, the Editor of The New Statesman and Ritchie Calder, now Lord Ritchie- Calder, came down to help. But the dominant figure was a priest called Father Grozier. He never failed. He seemed to be everywhere all the time; and his very presence brought comfort, and revived confidence and courage, to thousands of people.

The people of the East End of London - the true cockneys - are a race apart. Most of the men were dockers, all the women cosy. Taken as a whole, they were warm, affectionate, gay, rather reckless, and almost incredibly brave. Sometimes the language was pretty rough, but it was so natural and innocent that it never jarred. One day I came across a small boy crying. I asked him what the matter was, and he said: "They burnt my mother yesterday." Thinking it was in an air-raid, I said: "Was she badly burned?" He looked up at me and said, through his tears: "Oh yes. They don't muck about in crematoriums." I loved them, and I am glad to have been close to them in their hour of supreme trial.