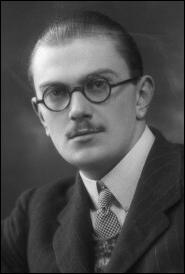

Charles Howard, 20th Earl of Suffolk

Charles Henry George Howard, the son of Henry Howard, 19th Earl of Suffolk, and his American wife, the former Margaret Hyde Leiter, sister of Mary Victoria Leiter, the wife of George Curzon, and daughter of the American businessman Levi Leiter, the founder of the Marshall Field & Company retail empire. (1)

The couple had met in India. "Henry... was a dashing sportsman and ADC to the Viceroy, Lord Curzon. She was visiting her sister, who was Curzon's wife. Henry had a title and an ancestry that dated back to the routing of the Armada. She possessed beauty, a love of adventure and one of the largest fortunes in America." (2)

Henry Howard owned Charlton Park in Malmesbury, one of the largest estates in England. Howard was killed in the First World War at the Battle of Istabulat on 21st April, 1917. Therefore, at the age of 11 he became the "head of one of the oldest families in England whose line had not changed in hundreds of years." (3)

Charles Howard, 20th Earl of Suffolk

Charles Howard was educated at home, notably by a French governess who had taught him to speak her language fluently. He attended Osborne Royal Naval College, but began to show the "first signs of what would become a disregard for convention and a dislike of excessive discipline." (4)

In 1921, aged fifteen, the Duke of Suffolk moved to Radley College, which proved more sympathetic to his temperament. However,he quit in 1923 to join the windjammer Mount Stewart as an apprentice officer. He also had a sheep farm in Australia. During this period he became known to his friends as "Mad Jack" and carried "a pair of revolvers he named Oscar and Genevieve". (5)

University of Edinburgh

Suffolk was extremely intelligent and eventually enrolled at the University of Edinburgh. Professor Neil Campbell later claimed that his first impression of Suffolk was of "a tall, striking looking, bold, adventurous looking man, more of a rollicking historical novel than an undergraduate about to endure the drudgery and hard work necessary for a serious degree in science... Naturally, his tutors and lecturers regarded the decision of a restless wanderer became a scientist as little more than a passing whim of the aristocracy." (6)

Suffolk was often in conflict with his mother and turned "his back on the traditional expectations of a great nobleman by marrying an actress", Mimi Crawford (Minnie Mabel Forde), in 1934. She was the daughter of A. G. Forde-Pigott, the former stage manager at the Alhambra Theatre. Mimi acted in several musical comedies including and Chelsea Nights (1929) and An Old World Garden (1929). Mimi had made her debut in opera in May 1931 in Die Fledermaus at Covent Garden before George V. (7)

In 1937 Suffolk was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. The following year he graduated with a first-class honours degree in chemistry and pharmacology. Kerin Freeman, the author of The Civilian Bomb Disposing Earl: Jack Howard and Civilian Bomb Disposal in WW2 (2014), commented: "Combining a charming manner and the easy courtesy of a nobleman... Jack was filled with hope for the future. By his side was his supportive, intelligent wife and healthy sons - the family lineage safe... His warm enigmatic charm made it effortless for him when making friends within the aristocratic or the working class, as he slotted easily into either niche... His pose was that of a dilettante with his always present cigarette holder which he held with a grace and dexterity of an artist." (8)

Rescue of Nuclear Scientists

On the outbreak of the Second World War the Duke of Suffolk attempted to join the Scots Guards but was rejected because he had previously had rheumatic fever. (9) He used family connections to be granted an interview with Dr. Herbert J. Gough, at the Ministry of Supply. He later recalled: "I was frightened at being landed with a titled member of Society about whom I knew so little. Such work as ours could carry no one who was not there on technical merit. In that frame of mind I saw Suffolk. His enthusiasm was tremendous. Before long his infectious personality, his gay buccaneering spirit won me completely." (10)

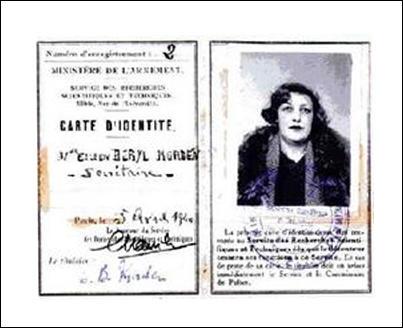

Suffolk was appointed as Liaison Officer for the British Department of Scientific and Industrial Research. As Suffolk spoke French fluently and had experience in engineering, Gough decided that he should became the government's liaison officer with France's armaments ministry. Suffolk and Eileen Beryl Morden, his secretary and personal assistant, were sent to France. While in France Suffolk spent time with John Desmond Bernal and Solly Zuckerman, who had been conducting tests on the effects of bomb blasts on chimpanzees (as substitutes for humans). Bernal and Zuckerman were in Paris to discuss similar experiments in France. (11)

attached to The Scientific and Technological Research Service. (May, 1940)

Suffolk was given the task of bringing to London two leading nuclear scientists, Lev Kowarski and Hans von Halban. They travelled to England on the British tramp ship SS Broompark with 33 other eminent scientists, with their families, 26 drums of heavy water (water that contained high levels of deuterium), the world’s entire stock at the time, France's stocks of uranium, industrial diamonds (worth some £400 million) and 600 tons of specialist machine tools, in an attempt to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Nazis. They arrived at Falmouth on 21st June, 1940. (12)

Suffolk was told to report to Harold Macmillan, Parliamentary Secretary at the Ministry of Supply. In his memoirs Macmillan recalled "a young man of somewhat battered appearance, unshaven, with haggard eyes" who combined "charm and eccentricity". Suffolk explained to Macmillan that he had brought over a large consignment of diamonds, some French scientists and "something called heavy water". (13)

This operation was successful but it remained a state secret and Herbert Morrison, a member of the War Cabinet, briefed Parliament about it in a closed session. He told MPs of the valuable material that had been obtained but the identity of Suffolk was kept a secret. Initially, this material was stored at Windsor Castle before being transferred to Cambridge, where ongoing atomic research ultimately formed the basis for the successful Allied effort to build a nuclear bomb. (14)

Duke of Suffolk: Bomb Disposal Unit

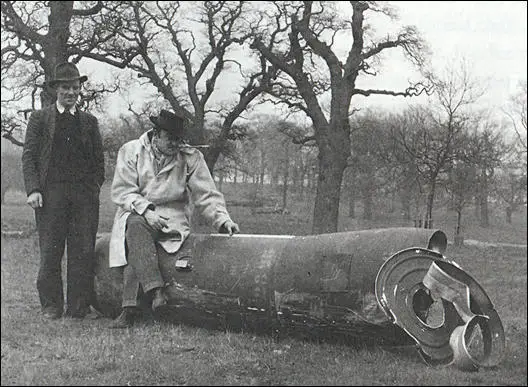

By September 1940 there were 3,759 unexploded bombs (UXB) in London. At first the main reason for this was faulty mechanism. However, within a few weeks it became clear that Germany had changed its strategy. Some bombs had been fitted with a sophisticated time-delay mechanism instead of a simple impact fuse. This was to ensure that the bombs would cause maximum havoc in the area where they fell, with premises evacuated and roads closed until they could be defused or moved to the "bomb cemetery". (15)

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) had the problem of dealing with UXBs. A warden would arrange for all premises to be evacuated and all roads within a 600 yard radius of the unexploded bomb. At the beginning of the war it is estimated that one in ten bombs during the early days of the Blitz were "duds". When the ARP discovered a German bomb they would inform the Bomb Disposal Unit (BDU) and skilled men from the Royal Engineers would be sent to remove the fuse. (16)

The government decided that a Unexploded Bomb Committee (UXBC) should be formed under the chairmanship of Dr. Herbert J. Gough, Director-General of Scientific Research. Gough then set-up a Research Sub-Committee (RSC), a weekly conference of scientists from the key ministries and laboratories that could react more swiftly to technical problems requiring rapid solutions. This included the co-ordinating of experimentation on fuzes. One of the RSC's first decisions was to commission a company to produce a "fuze discharger". (17)

The Duke of Suffolk became aware of the UXBC and asked Gough if he could get involved in this work. When an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station Gough took Suffolk with him. "The highly-dangerous 'game' of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination." (18)

M. J. Jappy, the author of Danger UXB (2001) has pointed out: "Dr Gough at the Ministry of Supply set Lord Suffolk out on what was to be his most daring venture yet: the world of bomb disposal. His health had prevented him going on active service but with characteristic disregard for rules and regulations, he bought himself a large van and kitted it out with the necessary equipment to investigate methods of defuzing unexploded bombs. His high level connections aided his maverick approach and eventually a small team of soldiers was seconded to him to help him with his work." (19)

The Duke of Suffolk's detachment consisted of himself, his secretary Eileen Beryl Morden, and his chauffeur, Fred Hards. The first scheme that Gough asked Suffolk to devise was a method for burning out the filling from bombs that could be steamed out, or where corrosion prevented the removal of the base plate by hand. To do this a "beaked crucible containing about six pounds of thermite was placed about three or four inches above the nose weld of the bomb casting". (20)

Over the next few months successfully dealt with 34 unexploded bombs. He was described as being "tall and debonair, often wearing a stetson, fawn duffel coat and sporting a matinee idol moustache, Howard would smoke with his 9-inch cigarette holder as he pondered the latest UXB." (21) Harold Macmillan later recalled: "I have had the good fortune to meet many gallant officers and brave men, but I have never known such a remarkable combination in a single man of courage, expert knowledge and indefinable charm." (22)

James Owen, the author of Danger UXB: The Heroic Story of the WWII Bomb Disposal Teams (2010), has pointed out that his bomb disposal work was sometimes criticised: "One officer accused him of carelessness after a five-hundred-kilogram bomb half wrecked a house while Suffolk was trying to neutralise its fuze with gelignite. The Earl did his best to defend himself against the charge that his team were meddlers. A few weeks later, however, a detachment of the East Surreys stationed in Richmond Park complained about several violent explosions set off by Suffolk that had, without warning, sprayed red-hot metal close to the guard room and officers' mess." (23)

Herbert J. Gough admitted that "he (Suffolk) gave the appearance of being slapdash at times". Lieutenant John Hudson of the bomb disposal unit, was another person who had misgivings about the Duke of Suffolk's approach: "He was a very colourful, very odd man. He used to have a pistol in a holster under his arm and when he wanted his van he would fire his pistol twice in the air, that sort of thing. He had a very pretty girl as a sort of secretary, we all envied him her... We didn't care for Suffolk at all. He wasn't disciplined, and he wasn't one of us." (24)

One of the major criticisms of Suffolk was that he took unnecessary risks: "His apparent disregard for the safety of those around him was anathema to the officers of the Royal Engineers. The regulations were clear: only those who were absolutely necessary should be in the vicinity when defuzing was taking place. It was very rare indeed for there to be any more than one person anywhere near the bomb after it had been uncovered." (25)

Richard Tunbridge, tells the story of how his grandfather encountered Suffolk in the spring of 1941: "My grandparent's shop had been damaged on numerous occasions but they kept it open as they were the only newsagents functioning in a heavily bombed area. Getting stock was very difficult and my grandfather used to travel all over London to find supplies, often bringing these back on a handmade barrow. They were about to give up when a remarkable event occurred. They woke up one morning to local pandemonium; an unexploded parachute landmine was hanging from a building. Everyone rushed into the shelter but later that morning a bizarre event occurred. A limousine pulled up and two men and a woman got out and came into the shelter. This smartly dressed trio announced themselves as Lord Howard, Earl of Suffolk, his chauffeur and his secretary. Everyone was amazed when they said they were the ‘Holy Trinity' bomb disposal team! They changed into overalls and went about defusing the landmine with the secretary taking detailed notes for future reference." (26)

On Tuesday, 12th May, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the Belvedere Marshes, just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty. A stethoscope was called for and preparations were made to sterilize the bomb. The bomb exploded at 3.20 pm and created a crater 5 ft in diameter. Suffolk and seven sappers were killed immediately. Rescuers found "Beryl Morden in an extremely serious condition. Fred Hands had managed to drag himself a few yards and died calling for Suffolk... Beryl, who had been in the service of the Earl for eleven months, sadly succumbed to her injuries and died in the ambulance." (27)

There were fourteen people around the bomb when it exploded. No trace at all could afterwards be found of four of them. "Some fragments of clothing and feet were identified as belonging to Suffolk, but in essence all that survived of him was the silver cigarette case." Among the dead were Staff Sergeant Jim Atkins, who had been operating the stethoscope, as well as Sappers Jack Hardy, Reg Dutson and Bert Gillett, and Driver David Sharratt. Six other soldiers had very serious injuries. (28)

A bomb disposal expert, William Wells, later argued: "It seemed a blunder on the part of the higher authorities to employ Lord Suffolk on bomb disposal experiments. He was a courageous man, but too adventurous, too much the showman for the cold-bloodied business of bomb disposal experimental work." Lieutenant John Hudson agreed: "We were all very thankful to have him off our chests, but we were very sorry that he took a lot of our chaps with him... He was an amateur, the one and only amateur bomb disposer... I mean, to have people standing around watching you in bomb disposal just wasn't done." (29)

On 15th July 1941, King George VI approved the George Cross for Lord Suffolk and Commendations for Eileen Beryl Morden, and Fred Hards. Lord Beaverbrook wrote to Mimi Howard: "I write with deep pleasure to tell you that the courageous conduct of your late husband while engaged in the service of the ministry is to receive the George Cross... The public recognition to his bravery and devotion to duty is a fitting tribute to one who gave his life for his country and that the safety of others might be preserved." (30)

Primary Sources

(1) The Liverpool Echo (2nd July, 1955)

All through World War II, and four a long time after it, countless lives were saved by a group of selfless, silent men - the volunteer heroes of bomb disposal units, the scientists and engineers who worked continuously in the shadow of sudden death. Many of these brave men did lose their lives in the pursuit of their hazardous work, but there were always others ready and willing to take their place.

Between 1940 and 1945, no fewer than 50,000 unexploded bombs were examined and disposed of in Great Britain alone. Among the fearless pioneers whose sensitive hands unravelled the mysteries of each new and terrifying fuse was Charles Henry Howard, 20th Earl of Suffolk and 13th Earl of Berkshire...

When war came in 1939, Lord Suffolk was rejected as unfit for military service: his earlier illness had left its mark. However, a close friend recommended him to the Ministry of Suupply, and his character, enthusiasm and learning made a deep impression on Dr. Herbert J. Gough, Director-General of Scientific Research. Dr. Gough was not concerned with titles; he simply wanted the best man he could get.

Lord Suffolk wanted impatiently for a new opportunity to serve his country. It came when an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station. Dr. Gough went to see it and Suffolk joined him. The highly-dangerous "game" of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination.

Suffolk revelled in his work, but was always conscious of its extreme danger. Often, he would order his men to a safe distance while he worked on alone.

At home, he never mentioned his own efforts, but sang the praises of his team of seven assistants. Off duty, he would often entertain them at a private party, and its says much of his leadership and discipline was never relaxed. A wonderful spirit bound him and his men together - whether working with fuses, burning into bombs, experimenting with oxy-acetylene burning, or sawing bombs in two.

But on Tuesday, May 12, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the "Marshes", just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty Dr. Gough was a little nervous about it, and drove to the "Marshes" to assure himself that Lord Suffolk was taking every possible precaution. When he got back to his office, however, he was greeted with the tragic news that the bomb had exploded and that Suffolk and his gallant men were dead.