Bomb Disposal Unit

The Air Raid Precautions (ARP) had the problem of dealing with unexploded bombs (UXB). Herbert J. Gough Director-General of Scientific Research, was given responsibility of dealing with UXB. In November, 1939, Gough and three other colleagues from the Royal Engineers, dealt with the first two unexploded bombs dropped on England in November 1939. (1)

A warden would arrange for all premises to be evacuated and all roads within a 600 yard radius of the unexploded bomb. At the beginning of the war it is estimated that one in ten bombs during the early days of the Blitz were "duds". When the ARP discovered a German bomb they would inform the Bomb Disposal Unit (BDU) and skilled men from the Royal Engineers would be sent to remove the fuse. (2)

On 12th September 1940, a 2,200-pound bomb had fallen close to St Paul's Cathedral and lay embedded in the ground near the front of the building. Its removal was a highly dangerous task for the bomb disposal squad, and took several days. Finally, the eight foot long missile was removed and taken on a lorry to what became known as the "bomb cemetery" on Hackney Marshes. The streets on its route was cleared in case it went off prematurely. on 15th September it was exploded in controlled conditions, where it made a crater one hundred feet in diameter. (3)

Unexploded Bombs in London

By September 1940 there were 3,759 UXBs in London. At first the main reason for this was faulty mechanism. However, within a few weeks it became clear that Germany had changed its strategy. Some bombs had been fitted with a sophisticated time-delay mechanism instead of a simple impact fuse. This was to ensure that the bombs would cause maximum havoc in the area where they fell, with premises evacuated and roads closed until they could be defused or moved to the "bomb cemetery". (4)

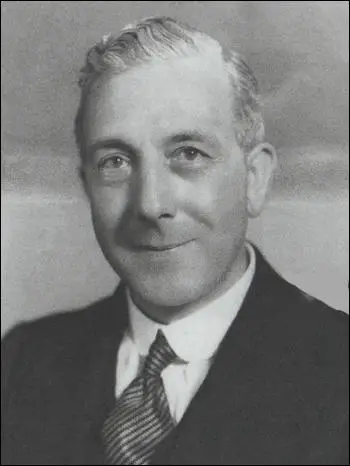

In 1940 the government decided that a Unexploded Bomb Committee (UXBC) should be formed under the chairmanship of Dr. Herbert J. Gough, Director-General of Scientific Research. Gough then set-up a Research Sub-Committee (RSC), a weekly conference of scientists from the key ministries and laboratories that could react more swiftly to technical problems requiring rapid solutions. This included the co-ordinating of experimentation on fuzes. (5)

The Germans began dropping bombs with two fuze pockets. The first being the time delay (fuze 17) and the second the anti-handling fuze 50 that required a movement of less than a millimetre to activate the trembler switch. The process of attaching the unwieldy clock-stopper was more than enough to cause the 50 fuze to detonate. Scientists working on the problem developed a BD discharger. A mixture of alcohol, benzine and salt was forced into the fuze and if left for thirty minutes, the fuze would become inert and the clock-stopper could be attached. (6)

People got used to this lurking hazard of unexploded bombs and after a while they refused to have their life interrupted by warnings of an unexploded bomb. Vere Hodgson, who helped to run a local charity in Notting Hill Gate, pointed out that when a large section of Hyde Park was cordoned off, with seats resting against the rope carrying placards marked "BEWARE - UXB!". However, Hodgson pointed out that people were peacefully sitting on the seats and some had penetrated the barrier and were relaxing on the grass inside. (7)

Frederick Leighton-Morris removed a 50kg bomb from his neighbour's flat in Jermyn Street, Mayfair, and decided to dump it in St James's Park. He was arrested when he put it down to have a well-earned rest. The magistrate praised his courage but fined him £100. You cannot decide, he was told, "in which part of London a delayed action bomb should go off". On appeal the fine was reduced to a more modest £5. (8) In court he pointed out that he had been rejected from national service for health reasons, but it was later reported that as a result of the case he was allowed to join the Royal Engineers. (9)

In September, 1940, George VI announced that "in order that they (Civil Defence workers) should be worthily and promptly recognised, I have decided to create, at once, a new mark of honour for men and women in all weeks of civilian life" for valour on the home front, as there were medals for those at the battlefront. The George Cross was intended to be the civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross, which was awarded for "acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstances of extreme danger" Most of the medals went to members of the bomb disposal squads. (10)

Non-Combatant Corps

At the beginning of the war conscientious objectors who refused to join the armed forces became members of the Non-Combatant Corps (NCC). It consisted of fourteen companies totaling 6,766 men and took part in all aspects of the war effort, apart from those that required the handling of weapons. By the end of 1940, 123 members of the BDU's had been killed and 67 wounded. It was therefore decided in January 1941, to send two companies of the NCC to London to clear bomb sites. (11)

Christopher Wren, was a member of the NCC who was sent to London: "I thought that it would be very good to destroy armaments and at the same time protect people. Both aspects seemed to fit with why I had become a non-combatant. The training was minimal. We went to Chester and were under canvas on the racecourse… We were told we would be going to London because there was more to be done down there… A few weeks later we were sent to Chelsea Barracks for real training. We really enjoyed that. It was with the Royal Engineers and everything was enjoyable. No prejudice at all." (12)

Tony White was another conscientious objector who carried out bomb-disposal work. "It was doing something constructive in the sense that you were digging out bombs that were meant to harm, immunizing them, and you could see it as a direct service for the community. But the major reason was my proving something to myself, that I wasn't ‘dodging the column'… I didn't want to escape the risk and here was a chance to prove my sincerity, not in the front line but dangerous… There were several 1,000 pounders that we got, about 4 or 5 feet long, they were a pretty good size. They were heavy of course, and we got them out by winching them out, with a tripod type of rig to haul them out. We'd take them away and try to neutralize them. You'd screw in and make a hole in the casing trying not to disturb the fuse… that job had to be done very carefully, and then we'd inject steam which would neutralize the power or the explosive and then one could remove the fuse safely. And then the officer would retreat to what was theoretically a safe distance and then explode it with an electrical device. This was when the thing could explode before the officer had got far enough away, he was always the one at the greatest risk and we did suffer casualties. You were never sure when you moved the bomb out of its hole… if you'd disturbed the mechanism and there was always the risk that the thing might explode." (13)

volunteered to work in the bomb disposal unit.

The bomb-disposal unit had the skilled and dangerous task of removing the device of making it safe. One of the major problems was the bombs usually penetrated through earth and tarmac to lie deep underground, making it extremely difficult and perilous to defuse them. As Juliet Gardiner has pointed out: "Throughout the war, bomb disposal was a perpetual deadly game of being one step ahead. As soon as the sappers worked out how one fuse could be neutralized, it seemed the Germans would adapt it or invent another that would test the ingenuity - and courage - of the soldiers (and those 350 or so commanding officers who had volunteered to help) to the very limit." (14)

Charles Howard, Duke of Suffolk

Dr. Herbert J. Gough, was appointed as Director-General of Scientific Research. When an unexploded bomb fell on Deptford Power Station. Dr. Gough went to see it and took his friend, Charles Howard, 20th Duke of Suffolk, with him. "The highly-dangerous 'game' of removing fuses became the young earl's new occupation. Dr. Gough formed the first and only Experimental Field Unit, and put Suffolk in charge of it. As raid after raid left in his wake deadly unexploded bombs, Suffolk and his men would remove the fuses and send more interesting examples to H.Q. for examination." (15)

M. J. Jappy, the author of Danger UXB (2001) has pointed out: "Dr Gough at the Ministry of Supply set Lord Suffolk out on what was to be his most daring venture yet: the world of bomb disposal. His health had prevented him going on active service but with characteristic disregard for rules and regulations, he bought himself a large van and kitted it out with the necessary equipment to investigate methods of defuzing unexploded bombs. His high level connections aided his maverick approach and eventually a small team of soldiers was seconded to him to help him with his work." (16)

Duke of Suffolk's detachment consisted of himself, his secretary Eileen Beryl Morden, and his chauffeur, Fred Hards. The first scheme that Gough asked Suffolk to devise was a method for burning out the filling from bombs that could be steamed out, or where corrosion prevented the removal of the base plate by hand. To do this a "beaked cruciblecontaining about six pounds of thermite was placed about three or four inches above the nose weld of the bomb casting". (17)

Over the next few months the team successfully dealt with 34 unexploded bombs. He was described as being "tall and debonair, often wearing a stetson, fawn duffel coat and sporting a matinee idol moustache, Howard would smoke with his 9-inch cigarette holder as he pondered the latest UXB." (18) Harold Macmillan met Suffolk in 1940: "I have had the good fortune to meet many gallant officers and brave men, but I have never known such a remarkable combination in a single man of courage, expert knowledge and indefinable charm." (19)

James Owen, the author of Danger UXB: The Heroic Story of the WWII Bomb Disposal Teams (2010), has pointed out that his bomb disposal work was sometimes criticised: "One officer accused him of carelessness after a five-hundred-kilogram bomb half wrecked a house while Suffolk was trying to neutralise its fuze with gelignite. The Earl did his best to defend himself against the charge that his team were meddlers. A few weeks later, however, a detachment of the East Surreys stationed in Richmond Park complained about several violent explosions set off by Suffolk that had, without warning, sprayed red-hot metal close to the guard room and officers' mess." (20)

Lieutenant John Hudson of the bomb disposal unit, was another person who had misgivings about the Duke of Suffolk's approach: "He was a very colourful, very odd man. He used to have a pistol in a holster under his arm and when he wanted his van he would fire his pistol twice in the air, that sort of thing. He had a very pretty girl as a sort of secretary, we all envied him her... We didn't care for Suffolk at all. He wasn't disciplined, and he wasn't one of us." (21)

One of the major criticisms of Suffolk was that he took unnecessary risks: "His apparent disregard for the safety of those around him was anathema to the officers of the Royal Engineers. The regulations were clear: only those who were absolutely necessary should be in the vicinity when defuzing was taking place. It was very rare indeed for there to be any more than one person anywhere near the bomb after it had been uncovered." (22)

Richard Tunbridge, tells the story of how his grandfather encountered the Duke of Suffolk in the spring of 1941: "My grandparent's shop had been damaged on numerous occasions but they kept it open as they were the only newsagents functioning in a heavily bombed area. Getting stock was very difficult and my grandfather used to travel all over London to find supplies, often bringing these back on a handmade barrow. They were about to give up when a remarkable event occurred. They woke up one morning to local pandemonium; an unexploded parachute landmine was hanging from a building. Everyone rushed into the shelter but later that morning a bizarre event occurred. A limousine pulled up and two men and a woman got out and came into the shelter. This smartly dressed trio announced themselves as Lord Howard, Earl of Suffolk, his chauffeur and his secretary. Everyone was amazed when they said they were the ‘Holy Trinity' bomb disposal team! They changed into overalls and went about defusing the landmine with the secretary taking detailed notes for future reference." (23)

On Tuesday, 12th May, 1941, a bomb for examination by Lord Suffolk's squad was taken to the Belvedere Marshes, just outside south-east London. It was an aged bomb, about 18 months old, and very rusty. A stethoscope was called for and preparations were made to sterilize the bomb. The bomb exploded at 3.20 pm and created a crater 5 ft in diameter. Suffolk and seven sappers were killed immediately. Rescuers found "Beryl Morden in an extremely serious condition. Fred Hands had managed to drag himself a few yards and died calling for Suffolk... Beryl, who had been in the service of the Earl for eleven months, sadly succumbed to her injuries and died in the ambulance." (24)

There were fourteen people around the bomb when it exploded. No trace at all could afterwards be found of four of them. "Some fragments of clothing and feet were identified as belonging to Suffolk, but in essence all that survived of him was the silver cigarette case." Among the dead were Staff Sergeant Jim Atkins, who had been operating the stethoscope, as well as Sappers Jack Hardy, Reg Dutson and Bert Gillett, and Driver David Sharratt. Six other soldiers had very serious injuries. (25)

A bomb disposal expert, William Wells, later argued: "It seemed a blunder on the part of the higher authorities to employ Lord Suffolk on bomb disposal experiments. He was a courageous man, but too adventurous, too much the showman for the cold-bloodied business of bomb disposal experimental work." Lieutenant John Hudson agreed: "We were all very thankful to have him off our chests, but we were very sorry that he took a lot of our chaps with him... He was an amateur, the one and only amateur bomb disposer... I mean, to have people standing around watching you in bomb disposal just wasn't done." (26)

Deaths of BDU members

One newspaper reported that throughout the Second World War "countless lives were saved by a group of selfless, silent men - the volunteer heroes of bomb disposal units, the scientists and engineers who worked continuously in the shadow of sudden death. Many of these brave men did lose their lives in the pursuit of their hazardous work, but there were always others ready and willing to take their place." (27)

Between 1940 and 1945, no fewer than 50,000 unexploded bombs were examined and disposed of in Great Britain. The deaths of members of the Bomb Disposal Unit did not end when peace was achieved in 1945. Unexploded bombs continued to be discovered. By 1947, 490 members of the BDU had been killed in the battle to extract those "great, torpid, iron pigs from the holes" and render them harmless. (28)

Primary Sources

(1) T. P. Peters, an Air Raid Warden in East Grinstead, wrote about his experiences during the Second World War in his book, Reminiscences (1945).

Unexploded German bombs were very dangerous. The Chief Warden and I would go and inspect the holes armed with rods, to enable him to fill up the necessary forms, etc., for the Bomb Disposal Unit. Once when going to Gulledge Farm to inspect an unexploded bomb, we were informed it had just gone off. Next came the Hoskyns Farm bomb, where a one-ton unexploded bomb fell only ten feet from the house. It was decided to evacuate the area at once. The BDU arrived and confirmed this and stated no one must go near it for ninety-six hours.

(2) John Bryan Miller, Saints and Parachutes (1951)

The policeman waved his hands towards the rosebed which edged the path. There, at full length, almost entirely buried in the soil, was lying one of the largest types of magnetic mines, badly damaged and in an exceedingly dangerous condition. We had everybody out from all the houses at once.

Unfortunately, the fuse was underneath the mine and I had to make one of the cold-blooded calculations which are so common on these occasions. The houses, though charming, were worth perhaps £1500 each and if they were completely destroyed no harm would be done to the war effort. The mine, I could see, was a standard type and was not likely to yield any secrets. In other words, it was a case, in the jargon of the Service, where "damage could be accepted".

It would be possible to request one of my officers to dig a hole under the mine, crawl in, and work on it from underneath. Alternatively, I could call up a boiler and a steam hose, and request my friend to stand over the mine and dissolve the explosive filling with steam, till so little was left that if it did go up nobody would lose anything but a few windows. But either method was so dangerous that it would only have been justified if the mine had been lying in a vital spot, a power house, an important telephone exchange, a water works, or something of that sort. I decided to trust to luck and an ordinary municipal steamroller.

It is a cardinal principle of mining that you should carry out every possible process from a distance of 200 yards, under cover. Certain operations have to be performed actually straddling the mine, and these cannot be avoided, but there is a surprising amount that can be done at the end of a 200-yard line. My plan of action was to make fast one end of a wire cable to a projection on the mine and the other to a steamroller, and then very gently back the roller down the hill, heave the mine out of its hole and expose the fuse for attention. The joy about these operations is that everybody is keen to help, everybody wants the mine cleared, and I have never asked in vain for any piece of apparatus which was needed, however bizarre. The answer was always 'Yes'. A steamroller was immediately produced; there was an excellent driver in charge, who grasped perfectly what he had to do and quite understood that there must be absolutely no jerk at any stage of the proceedings. We made fast the wire, took cover in a position from which we could watch and signaled the driver to let his roller slide slowly down the hill. The wire took the strain sweetly, the huge bulk of the mine heaved slowly up out of the rosebed; when suddenly there was an appalling explosion.

When the dust subsided, there was practically nothing left of the circle of houses. The curious thing was that the people were angry. They said that the thing had been lying there a week and if we had only left it alone, they would never have lost their property.

(3) Christopher Wren, a conscientious objector and a member of the Non-Combatant Corps, quoted by M. J. Jappy, in Danger UXB (2001) pages 92-93

I was a conscientious objector until Dunkirk…. I was horrified by the sight of civilians being shot at and bombed… that we (NCCs) were prepared to go and help… do anything that was needed to save life… I thought that it would be very good to destroy armaments and at the same time protect people. Both aspects seemed to fit with why I had become a non-combatant. The training was minimal. We went to Chester and were under canvas on the racecourse… We were told we would be going to London because there was more to be done down there… A few weeks later we were sent to Chelsea Barracks for real training. We really enjoyed that. It was with the Royal Engineers and everything was enjoyable. No prejudice at all.

(4) Tony White, a Methodist and conscientious objector, volunteered for bomb-disposal work. Quoted in Felicity Goodall, A Question of Conscience (1997) page 130

It was doing something constructive in the sense that you were digging out bombs that were meant to harm, immunizing them, and you could see it as a direct service for the community. But the major reason was my proving something to myself, that I wasn't ‘dodging the column' … I didn't want to escape the risk and here was a chance to prove my sincerity, not in the front line but dangerous… There were several 1,000 pounders that we got, about 4 or 5 feet long, they were a pretty good size. They were heavy of course, and we got them out by winching them out, with a tripod type of rig to haul them out. We'd take them away and try to neutralize them. You'd screw in and make a hole in the casing trying not to disturb the fuse… that job had to be done very carefully, and then we'd inject steam which would neutralize the power or the explosive and then one could remove the fuse safely. And then the officer would retreat to what was theoretically a safe distance and then explode it with an electrical device. This was when the thing could explode before the officer had got far enough away, he was always the one at the greatest risk and we did suffer casualties.

You were never sure when you moved the bomb out of its hole… if you'd disturbed the mechanism and there was always the risk that the thing might explode. There were all sorts of things like sensible safe distances and safe times and so on to mimimise the danger, but it was always there.

(5) Richard Tunbridge, The Tunbridge Family in the Second World War (May, 2019)

By the spring of 1941 my grandparent's shop had been damaged on numerous occasions but they kept it open as they were the only newsagents functioning in a heavily bombed area. Getting stock was very difficult and my grandfather used to travel all over London to find supplies, often bringing these back on a handmade barrow.

They were about to give up when a remarkable event occurred. They woke up one morning to local pandemonium; an unexploded parachute landmine was hanging from a building. Everyone rushed into the shelter but later that morning a bizarre event occurred. A limousine pulled up and two men and a woman got out and came into the shelter. This smartly dressed trio announced themselves as Lord Howard, Earl of Suffolk, his chauffeur and his secretary. Everyone was amazed when they said they were the ‘Holy Trinity' bomb disposal team! They changed into overalls and went about defusing the landmine with the secretary taking detailed notes for future reference. Next month the team were all killed whilst trying to defuse a bomb. They became an East End legend having defused over 30 bombs. The bravery of these three people convinced my grandparents to stay and try to keep the shop open.