British Foreign Policy: 1919-1939

In December, 1917, Leon Trotsky led the Russian delegation at Brest-Litovsk that was negotiating with representatives from Germany and Austria. Trotsky had the difficult task of trying to end Russian participation in the First World War without having to grant territory to the Central Powers. By employing delaying tactics Trotsky hoped that socialist revolutions would spread from Russia to Germany and Austria-Hungary before he had to sign the treaty. (1)

After nine weeks of discussions without agreement, the German Army was ordered to resume its advance into Russia. On 3rd March 1918, with German troops moving towards Petrograd, Lenin ordered Trotsky to accept the terms of the Central Powers and he reluctantly signed the Brest-Litovsk Treaty. "Russia had lost the Ukraine, Finland, her Polish and Baltic territories. In the Caucasus she had to make territorial concessions to Turkey... Three centuries of Russian Territorial expansion was undone." (2)

The treaty deprived "Russia of a territory nearly as large as Austria-Hungary and Turkey combined, with 56,000,000 inhabitants, or 32 per cent of her whole population; a third of her railway mileage, 73 per cent of her total iron ore, 89 per cent of her total coal production; and more than 5,000 factories and industrial plants. Moreover, Russia was obliged to pay Germany an indemnity of six billion marks." (3) The historian, John Wheeler-Bennett commented that the treaty was a "humiliation without precedent or equal in modern history." (4)

The Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919. As a result of the treaty Germany suffered the following penalties: (i) The surrender of all German colonies as League of Nations mandates. (ii) The return of Alsace-Lorraine to France. (iii) Cession of Eupen-Malmedy to Belgium, Memel to Lithuania, the Hultschin district to Czechoslovakia. (iv) Poznania, parts of East Prussia and Upper Silesia to Poland. (v) Danzig to become a free city; (vi) Occupation and special status for the Saar under French control. (vii) Demilitarization and a fifteen-year occupation of the Rhineland. (vii) German reparations of £6,600 billion. (viii) A ban on the union of Germany and Austria. (ix) Limitation of Germany's army to 100,000 men with no conscription, no tanks, no heavy artillery, no poison-gas supplies, no aircraft and no airships; (x) The German navy was allowed six pre-dreadnought battleships and was limited to a maximum of six light cruisers (not exceeding 6,100 tons), twelve destroyers (not exceeding 810 tons and twelve torpedo boats (not exceeding 200 tons) and was forbidden submarines. (5)

John Maynard Keynes wrote to David Lloyd George explaining why he was resigning: "I can do no more good here. I've on hoping even though these last dreadful weeks that you'd find some way to make of the Treaty a just and expedient document. But now it's apparently too late. The battle is lost. I leave the twins to gloat over the devastation of Europe, and to assess to taste what remains for the British taxpayer." (6)

The major aim of the peacemakers was to ensure that the principle of national groupings of central and eastern Europe. This was incredibly difficult and few ethnic groups were satisfied with what they were given. The creation of two new states - Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia at the expense of Austria-Hungary and the expansion of Poland at the expense of Germany and Russia, left eastern Europe more unstable than ever before. (7)

David Lloyd George who had been largely responsible for the Treaty of Versailles admitted in a memorandum in 1919, that the future would be difficult: "I cannot imagine any greater cause of future war than that the German people, who have proved themselves one of the most powerful and vigorous races in the world should be surrounded by a number of small states, many of them consisting of peoples who have never previously set up a stable government for themselves." (8)

Foreign Policy: 1920-1924

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organisation founded on 10 January 1920 as a result of the Paris Peace Conference. It was the first international organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. Its primary goals, as stated in its Covenant, included preventing wars through collective security and disarmament and settling international disputes through negotiation and arbitration. The League lacked its own armed force and depended on the victorious countries of the First World War. France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Japan were the permanent members of the executive Council and had the powers to enforce its resolutions, keep to its economic sanctions, or provide an army when needed.

After the war Lloyd George informed British military chiefs to plan defence spending on the assumption that no major war would occur for ten years. In 1922 the British government signed the Washington Naval Treaty. It was agreed that Britain would maintain parity with the United States in the building of battleships and a margin of five to three in the same class of vessel over Japan, the third largest naval power. Lloyd George agreed that all battleships under construction must be scrapped and that no new ones should be brought into service for ten years. Lloyd George willingly accepted the deal as his government could not afford to build new battleships. (9)

In the 1920s Britain and France were the two most dominant powers in Europe. The French government feared that in the future it would have problems with both Germany and Russia and wanted a military alliance with Britain. This was rejected by Britain who feared being drawn into another world war. In 1920, a Channel tunnel project was rejected by the foreign office on the grounds that "our relations with France never have been, are not, and probably never will be, sufficiently stable and friendly to justify the building of a channel tunnel." (10)

In July 1921, Winston Churchill, a member of Lloyd George's government, wrote that he saw the chief aim of British policy as the "appeasement of the fearful hatreds and antagonisms which exist in Europe and to enable the world to settle down." (11) However, he was totally opposed to join forces with France who signed treaties of mutual assistance with Poland, Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Yugoslavia in the 1920s. (12)

In May 1921 General Election the Italian Socialist Party won 24.7 per cent of the vote. The liberal, left of centre, Italian People's Party was second with 20.4 per cent and a right-wing nationalist coalition was third with 19.1 per cent. The Communist Party on Italy won over 4.6 per cent. Luigi Facta, of the IPP became the prime minister. On 28th October 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts, led by Benito Mussolini, gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. King Victor Emmanuel III refused the government request to declare martial law, which led to Facta's resignation. The King then handed over power to Mussolini who enjoyed wide support in the military and among the industrial and agrarian elites, while the King and the conservative establishment were afraid of a possible communist revolution. (13)

Raymond Poincaré, the French premier, grew increasingly annoyed that the British continued to spurn his offers of an alliance with Britain. In December, 1922, Poincaré wrote to the French ambassador in London: "Judging others by themselves, the English, who are blinded by their loyalty, have always thought that the Germans did not abide by their pledges inscribed in the Versailles Treaty because they had not frankly agreed to them.... We, on the contrary, believe that if Germany, far from making the slightest effort to carry out the treaty of peace, has always tried to escape her obligations, it is because until now she has not been convinced of her defeat.... We are also certain that Germany, as a nation, resigns herself to keep her pledged word only under the impact of necessity." (14)

Poincaré was outraged at successive failures by Germany to meet its payments, ordered the occupation of the industrial Ruhr region in January, 1923. It did not have the desired impact on Germany: "A wave of popular indignation and nationalisation swept across Germany in response to this occupation, the government ordered a policy of passive resistance to the French troops whose intention was to 'liberate' massive quantities of coal as payment in kind. Passive resistance merely put an even greater strain upon German's precarious finances, and in the second half of 1923 the mark collapsed against the American dollar and other major currencies." (15)

On August 31, 1923, a squadron of the Italian Navy bombarded the Greek island of Corfu and landed over 5,000 troops. As a result of the bombardment 16 civilians were killed, 30 injured and two had limbs amputated. The majority of those killed were children. Greece appealed to the League of Nations, but Antonio Salandra, the Italian representative to the League, informed the Council that he had no permission to discuss the crisis. As Mussolini pointed out, "the League is very well when sparrows shout, but no good at all when eagles fall out." Italy only left Corfu after Greece paid 50,000,000 lire to Italy. (16)

Foreign Policy: 1924-1929

Charles G. Dawes, an American banker, was asked by the Allied Reparations Committee to investigate the economic problems in Germany. His report, published in April, 1924, proposed a plan for instituting annual payments of reparations on a fixed scale. He also recommended the reorganization of the German State Bank and increased foreign loans. The Dawes Plan was initially a great success. The currency was stabilized and inflation was brought under control. Large loans were raised in the United States and this investment resulted in a fall in unemployment. The German people gradually gained a new faith in their democratic system and began to find the extremist solutions proposed by political figures such as Adolf Hitler as unattractive. (17)

Ramsay MacDonald became prime minister in 1924. MacDonald also took the post of foreign secretary but he had the capable Arthur Ponsonby as his deputy in the department. Both men had been strong opponents of the First World War and supporters of the League of Nations. Ponsonby wrote to MacDonald: "The incredible seems about to happen. We are actually to be allowed by an extraordinary combination of circumstances to have control of the Foreign Office and to begin to carry out some of the things we have been urging and preaching for years." (18)

MacDonald joined forces with the French prime minister, Édouard Herriot, to sign the Geneva Protocol. It was suggested legal disputes between nations would be submitted to the World Court. It also called for a disarmament conference in 1925. Any government that refused to comply in a dispute would be named an aggressor. Any victim of aggression was to receive immediate assistance from League members. According to Frank McDonough it was "an ingenious plan which linked collective security with compulsory arbitration in international disputes and set out a format to determine the aggressor and impose penalties in disputes between nations." (19)

MacDonald lost power after the 1924 General Election. The new foreign secretary, Austen Chamberlain, rejected the policy as he believed that it might involve Britain in all manner of conflicts. Chamberlain told King George V that his chief foreign policy aim was "to make the new position of Germany tolerable to the German people in the hope that, as they gain prosperity under it, they may in time became reconciled to it, and unwilling to put their fortunes again to the desperate hazard of war." (20)

In 1925 the German foreign minister Gustav Stresemann proposed that France, Germany and Belgium should recognize as permanent their frontiers that was agreed at Versallies. This included the promise not to send German troops into the Rhineland and the acceptance that Alsace-Lorraine was permanently part of France. The French foreign minister, Aristide Briand, agreed with Stressemann's proposals and along with Austen Chamberlain signed the Locarno Treaty. In return Germany was to be admitted to the League of Nations and the German government was promised an early end to the military restrictions on Germany. (21)

On signing the treaty Gustav Stresemann made the following statement: "The Treaty of Locarno, is destined to be a landmark in the history of the relations of States and peoples to each other. We especially welcome the expressed conviction set forth in this final protocol that our labours will lead to decreased tension among the peoples and to an easier solution of so many political and economic problems. We have undertaken the responsibility of initialing the treaties because we live in the faith that only by peaceful cooperation of States and peoples can that development be secured, which is nowhere more important than for that great civilized land of Europe whose peoples have suffered so bitterly in the years that lie behind us." (22)

In 1928 Aristide Briand and Frank. B. Kellogg signed the Kellog-Briand Pact (General Treaty for Renunciation of War). Sponsored by France and the United States, the Pact renounces the use of war and calls for the peaceful settlement of disputes. The US Senate ratified it in 1929 and over the next few years forty-six nations signed a similar agreement committing themselves to peace. Briand argued: "Among peoples who are geographically grouped together like the peoples of Europe there must exist a sort of federal link. It is this link which I wish to endeavour to establish... I am sure also that from a political point of view, and from a social point of view the federal link, without infringing the sovereignty of any of the nations which might take part in such as association, could be beneficial." (23)

Ramsay MacDonald returned to power following the 1929 General Election. He had always been opposed to the Treaty of Versailles. During the First World War he had said: "If German militarism is to be crushed, Germany must not be given as an inheritance from the war, the spirit of revenge." The removal of reparations, support for disarmament and the finding of peaceful solutions to international problems remained central objectives of British foreign policy under MacDonald. (24)

Foreign Policy: 1929-1937

In October 1929, the Wall Street Crash, produced a far-reaching depression. The first consequence of the United States financial collapse was the ending of American loans to Europe, which had been vital in stimulating recovery. "It is important to stress how much the depression damaged international co-operation. Unemployment rose everywhere, banks failed, industrial output fell alarmingly and agricultural prices collapsed. The widespread optimism of the free market, democracy and the international co-operation of the mid-1920s gave way to the pessimism, totalitarianism and self-preservation." (25)

In October 1931 Neville Chamberlain was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer. He continued with the policy of cutting public spending. Britain only had an army of 400,000 men and although a higher percentage of money was spent on the Royal Air Force, by 1932, it was only the fifth largest of the few air forces in the world. The fear of an air attack grew throughout the 1930s. It was not helped by Stanley Baldwin telling the House of Commons: "I think it is well for the man in the street to realise that no power on earth can protect him from being bombed. Whatever people may tell him, the bomber will always get through." (26)

MacDonald managed to persuade the sixty-six countries to attend a World Disarmament Conference in 1932. It was chaired by the Labour Party's Arthur Henderson. A conference in London in 1930 had agreed arms limitation agreements on naval disarmament. The conference was designed to extend this process to all weapons and armies. Although the British government's proposals of world disarmament was supported by most of the smaller nations but Germany, France, Italy and the Soviet Union opposed any wide-ranging agreements. In October 1933 Adolf Hitler withdrew Germany from the Disarmament Conference. (27)

In July 1934, the Soviet Union was allowed to join the League of Nations. Joseph Stalin became increasingly concerned that his country would be invaded by Nazi Germany. Stalin believed the best way to of dealing with Germany was to form an anti-fascist alliance with countries in the west. Stalin argued that even Adolf Hitler would not start a war against a united Europe. Adam B. Ulam, the author of Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) has argued: "Soviet diplomacy sought (in a much more realistic way than that of Britain and France) to avoid war. To do Stalin justice, he never made a secret greater than his desire to avoid war, or more precisely to avoid Russia's military involvement in one." (28)

In the final months of 1934, a survey was carried out of nearly 12 million British voters on foreign policy. The results showed overwhelming support for the government's policy of collective security, the League of Nations and disarmament. However, Ramsay MacDonald was suffering from poor health and on 7th June 1935, he went to see George V to tell him he was resigning as head of the National Government. Henry Channon, the Conservative MP for Southend, commented in his diary: "I am glad Ramsay (MacDonald) has gone: I have always disliked his shifty face, and his inability to give a direct answer. What a career, a life-long Socialist, then for 4 years a Conservative Prime Minister... He ends up distrusted by Conservatives and hated by Socialists." (29)

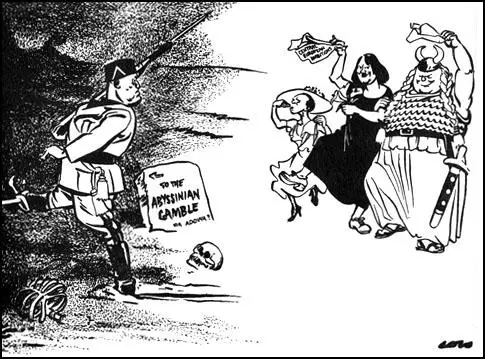

Stanley Baldwin became the new prime minister. He appointed Sir Samuel Hoare as foreign secretary as Sir Anthony Eden as minister for the League of Nations. Both men were warned by Sir Robert Vansittart, the permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office, Benito Mussolini, intended to invade Abyssinia and therefore "Italy would have to be bought off - let us use and face ugly words - in some form or Abyssinia will perish." (30) In June 1935, the cabinet decided to offer Mussolini the Ogadon province of Abyssinia, a twelve-mile corridor to the Gulf of Aden. Eden went to Italy to present these proposals to Mussolini, but he rejected them and promised to "wipe the name of Abyssinia from the map." (31)

On 3rd October 1935, Mussolini sent 400,000 soldiers to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Haile Selassie, the ruler of appealed to the League of Nations for help, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure. As the majority of the Ethiopian population lived in rural towns, Italy faced continued resistance. Haile Selassie fled into exile and went to live in England. Mussolini was able to proclaim the Empire of Ethiopia and the assumption of the imperial title by the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III. The League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions in November 1935, but the sanctions were largely ineffective since they did not ban the sale of oil or close the Suez Canal, that was under the control of the British. (32)

Adolf Hitler knew that both France and Britain were militarily stronger than Germany. However, their failure to take action against Italy, convinced him that they were unwilling to go to war. He therefore decided to break another aspect of the Treaty of Versailles by sending German troops into the Rhineland. The German generals were very much against the plan, claiming that the French Army would win a victory in the military conflict that was bound to follow this action. Hitler ignored their advice and on 1st March, 1936, three German battalions marched into the Rhineland. Hitler later admitted: "The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance." (33)

Hitler told the Reichstag: "All of us and our peoples have the feeling that we are at the turning-point of an age... Not we alone, the conquered of yesterday, but also the victors have the inner conviction that something was not as it should be, that reason seemed to have deserted men... Peoples must find a new relation to each other, some new form must be created... They make a mistake who think that over the entrance to this new order there can stand the word Versailles. That would be, not the foundation stone of the new order, but its gravestone." (34)

The British government accepted Hitler's Rhineland coup. Sir Anthony Eden, the new foreign secretary, informed the French that the British government was not prepared to support military action. The chiefs of staff felt Britain was in no position to go to war with Germany over the issue. The Rhineland invasion was not seen by the British government as an act of unprovoked aggression but as the righting of an injustice left behind by the Treaty of Versailles. Eden apparently said that "Hitler was only going into his own back garden." (35)

On the 19th July, 1936, Spain's prime minister, José Giral, sent a request to Leon Blum, the prime minister of the Popular Front government in France, for aircraft and armaments. The following day the French government decided to help and on 22nd July agreed to send 20 bombers and other arms. This news was criticised by the right-wing press and the non-socialist members of the government began to argue against the aid and therefore Blum decided to see what his British allies were going to do. (36)

Anthony Eden, the British foreign secretary, received advice that "apart from foreign intervention, the sides were so evenly balanced that neither could win." Eden warned Blum that he believed that if the French government helped the Spanish government it would only encourage Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini to aid the Nationalists. Edouard Daladier, the French war minister, was aware that French armaments were inferior to those that Franco could obtain from the dictators. Eden later recalled: "The French government acted most loyally by us." On 8th August the French cabinet suspended all further arms sales, and four days later it was decided to form an international committee of control "to supervise the agreement and consider further action." (37)

In Britain sympathies were divided. Those on "the Left" saw it as "a Holy war, a Jehad in which the Spanish Government stood embattled against the forces of evil". Whereas "others, no less transported by emotion, who longed for the victory of the insurgents with an equal fervour, and saw in its achievement the conquest of anarchy and godlessness, and the triumphant reassertion of the principles of Christian life". It has been claimed that as a result "both parties ignored or excused the barbarities that were inflicted by their own champions." (38)

Eden told the British prime minister, Stanley Baldwin that "The international situation is so serious that from day to day there was risk of some dangerous incident arising and even an outbreak of war could not be excluded." He argued that the two main aims of British policy should be "to secure peace" and to "keep this country out of war". This was viewed by the left another example of appeasing Hitler and Mussolini. Some historians have claimed that British ministers virtually blackmailed the French into accepting non-intervention. Frank McDonough believes that the "French were reluctant to become involved, not only out of fear of losing British support in a future European war, but because the Blum coalition was weak and feared active French involvement might precipitate a civil war on the streets of France." (39)

Paul Preston, the author of The Spanish Civil War (1986) has argued that "public opinion in Britain was overwhelmingly on the side of the Spanish Republic" and when defeat was certain, 70 per cent of those polled considered the Republic to be the the legitimate government. "However, among the small proportion of those who supported Franco, never more than 14 per cent, and often lower, were those who would make their crucial decisions. Where the Spanish war was concerned, Conservative decision-makers tended to let their class prejudices prevail over the strategic interests of Great Britain." (40)

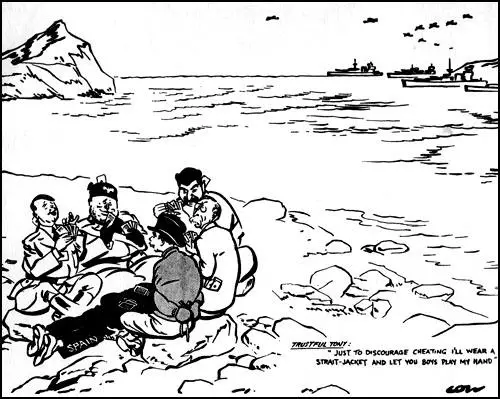

Baldwin called for all countries in Europe not to intervene in the Spanish Civil War. He also warned the French if they aided the Spanish government and it led to war with Germany, Britain would not help her. The first meeting of the Non-Intervention Committee met in London on 9th September 1936. Eventually 27 countries including Germany, Britain, France, the Soviet Union, Portugal, Sweden and Italy signed the Non-Intervention Agreement. Benito Mussolini continued to give aid to General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces and during the first three months of the Non-Intervention Agreement sent 90 Italian aircraft and refitted the cruiser Canaris, the largest ship owned by the Nationalists. (41)

The day after Germany signed the Non-Intervention Agreement, Adolf Hitler told his war minister, Field-Marshal Werner von Blomberg, that he wanted to give substantial aid to General Franco. (42) The British government was aware of this but "so long as non-intervention in Spain was imposed without too obvious infringements, so long as Germany remained less committed, politically and militarily, than Italy in the Civil War, some chance of a détente remained." (43)

Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, the Secretary of State for War, admitted that the government was fully aware that its Non-Intervention policy was unsuccessful. "What however it did do was to keep such intervention as there was entirely unofficial, to be denied or at least deprecated by the responsible spokesmen of the nation concerned, so that there was neither need nor occasion for any official action by Governments to support their nationals." (44)

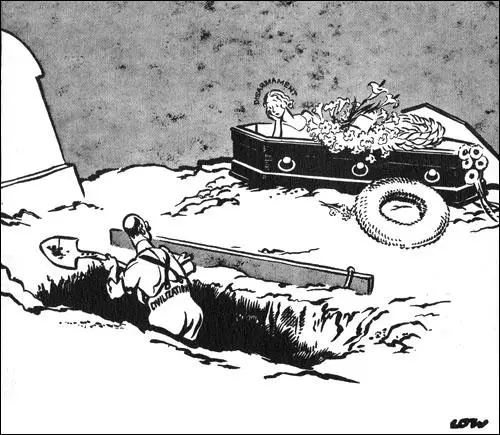

say, twenty-five years?", Evening Standard (12th March, 1936)

On 28th May, 1937, Stanley Baldwin resigned and replaced by Neville Chamberlain. As Chancellor of the Exchequer he had resisted attempts to increase defence spending. He now changed his mind and asked the defence policy requirements committee to look at different ways of funding this expenditure. It was suggested that £1.1 billion was financed through increased taxation and £400 million coming from increased government borrowing. It was suggested that of this sum, £80 million should be spent in air-raid precautions. (45)

In the Spanish Civil War the Nationalists with considerable help from Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, was gradually obtaining control of the country. The Spanish prime minister, Francisco Largo Caballero, came under increasing pressure from the Communist Party (PCE) to promote its members to senior posts in the government. He also refused their demands to suppress the Worker's Party (POUM). In May 1937, the Communists withdrew from the government. In an attempt to maintain a coalition government, President Manuel Azaña sacked Largo Caballero and asked Juan Negrin to form a new cabinet. The socialist, Luis Araquistain, described Negrin's government as the "most cynical and despotic in Spanish history." Negrin now began appointing members of the PCE to important military and civilian posts. This included Marcelino Fernandez, a communist, to head the Carabineros. Communists were also given control of propaganda, finance and foreign affairs. (46)

Negrin's government set out to limit the revolution and abolish the collectives. It argued that any revolution must be postponed until the war had been won. Revolution was seen as a distraction from the main business of winning the war. "It also threatened to alienate the middle class and peasants. Given the performance of the collectives, the Communists and their supporters had a number of points on their side. But the major reason why they took an anti-revolutionary line was to follow Soviet foreign policy strategy. The USSR wished to forge an alliance with Britain and France in a front against which would alarm and antagonise the western democracies and increase their hostility to the Soviet Union as well as setting them irrevocably against the Republic. The Communists therefore wanted to present the republic as a law-abiding democratic regime which deserved the approval of the western powers." (47)

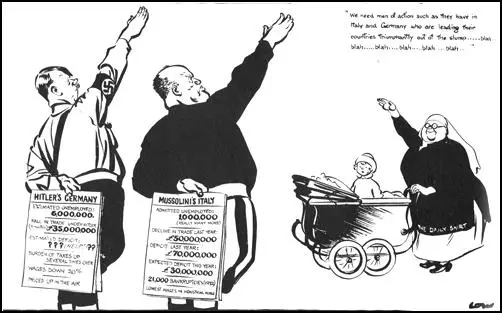

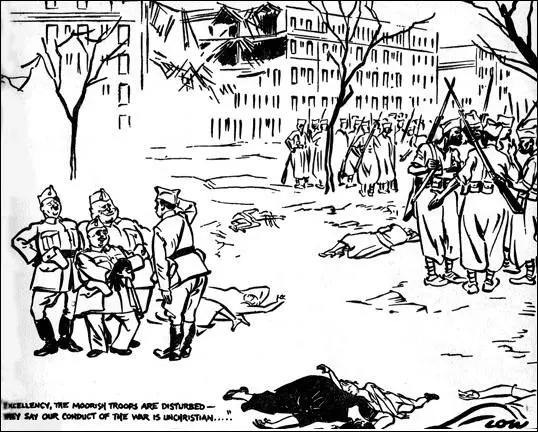

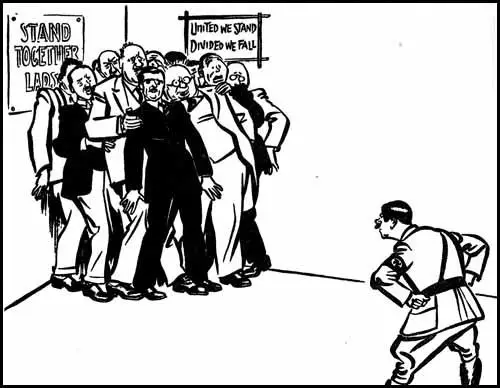

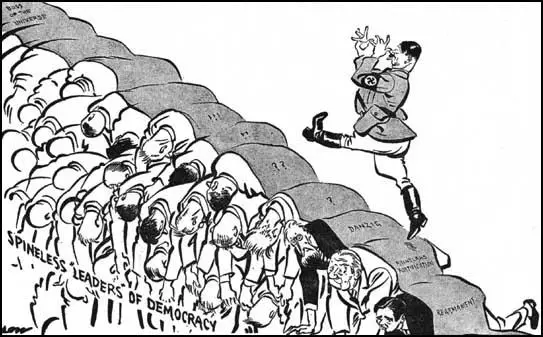

Cartoons by David Low criticizing Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini resulted in his work being banned in Germany and Italy. After the war it was revealed that in 1937 the German government asked the British government to have "discussions with the notorious Low" in an effort to "bring influence to bear on him" to stop his cartoons attacking appeasement. Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, went to see Low: "When Lord Halifax visited Germany officially in 1937, he was told that the Führer was deeply offended by Low's cartoons of him, and that the paper in which they appeared, the Evening Standard, was banned in Germany.... On Halifax's return to London, he summoned Low and told him that his cartoons were impairing the prime minister's policy of appeasement." (48)

References

(1) Lionel Kochan, Russia in Revolution (1970) page 280

(2) Adam B. Ulam, The Bolsheviks (1998) page 406

(3) William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1964) page 81

(4) John Wheeler-Bennett, Hindenburg: The Wooden Titan (1967) page 131

(5) James Taylor and Warren Shaw, Dictionary of the Third Reich (1987) pages 294-295

(6) Robert Skidelsky, John Maynard Keynes: Hopes Betrayed 1883-1920 (1983) page 369

(7) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 15

(8) David Lloyd George, memorandum (March, 1919)

(9) Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (1983) page 274

(10) Alan Sharp, Britain and the Channel Tunnel 1919-1920, Australian Journal of Politics and History (1979) page 210

(11) Winston Churchill, memorandum (June, 1921)

(12) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 16

(13) Adrian Lyttelton, The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy 1919-1929 (2009) pages 75-77

(14) Leopold Schwarzschild, World in Trance: From Versailles to Pearl Harbor (1943) page 140

(15) Simon Taylor, Germany 1918-1933: Revolution, Counter-Revolution and the Rise of Hitler (1983) page 51

(16) Elisabetta Tollardo, Fascist Italy and the League of Nations (2018) page 3

(17) James Stewart Martin, All Honorable Men (1950) page 46

(18) Austen Morgan, J. Ramsay MacDonald (1987) page 113

(19) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 18

(20) Martin Gilbert, The Roots of Appeasement (1966) page 112

(21) Norman Rich, Great Power Diplomacy Since 1914 (2003) pages 148–49

(22) Gustav Stresemann, speech after the signing of the Locarno Treaty (16th October, 1925)

(23) Aristide Briand, speech (7th September, 1929)

(24) Martin Gilbert, The Roots of Appeasement (1966) page 106

(25) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 20

(26) Stanley Baldwin, speech in the House of Commons (10th November, 1932)

(27) Austen Morgan, J. Ramsay MacDonald (1987) pages 218-219

(28) Adam B. Ulam, Stalin: The Man and his Era (2007) page 399

(29) Henry Channon, diary entry (June, 1935)

(30) Norman Rose, Vansittart: Study of a Diplomat (1978) page 165

(31) Anthony Eden, Facing the Dictators (1962) page 255

(32) Roy Hattersley, Borrowed Time: The Story of Britain Between the Wars (2007) page 398-399

(33) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 345

(34) Adolf Hitler, speech in the Reichstag (22nd March, 1936)

(35) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 27

(36) Patricia Knight, The Spanish Civil War (1998) page 67

(37) Antony Beevor, The Spanish Civil War (1982) page 110

(38) Frederick Winston Furneaux Smith, The Life of Lord Halifax (1965) pages 356-360

(39) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) pages 28-29

(40) Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War (1986) pages 137-138

(41) Patricia Knight, The Spanish Civil War (1998) page 67

(42) Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (2003) page 381

(43) Keith Middlemas, Diplomacy of Illusion (1972) page 42

(44) Frederick Winston Furneaux Smith, The Life of Lord Halifax (1965) pages 359-360

(45) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 40

(46) Paul Preston, The Spanish Civil War (1986) page 258

(47) Patricia Knight, The Spanish Civil War (1998) page 52

(48) Anthony Rhodes, Propaganda: The Art of Persuasion: World War II (1987) page 118

John Simkin