On this day on 29th September

On this day in 1348 the Black Death arrived in London. The first symptoms of the Black Death included a high temperature, tiredness, shivering and pains all over the body. The next stage was the appearance of small red boils on the neck, in the armpit or groin. These lumps, called buboes, grew larger and darker in colour. Eyewitness accounts talk of these buboes growing to the size of apples. The final stage of the illness was the appearance of small, red spots on the stomach and other parts of the body. This was caused by internal bleeding, and death followed soon after.

On this day in 1564 Robert Dudley become Earl of Leicester. For many years it was rumoured that Dudley was the lover of Queen Elizabeth. As the Master of the Horse he was the only man in England officially allowed to touch the Queen (he was responsible for helping Elizabeth mount and dismount when she went horse-riding). According to Dudley's biographer, Simon Adams: "Robert Dudley's peculiar relationship to Elizabeth began to attract comment. This relationship - which defined the rest of his life - was characterized by her almost total emotional dependence on him and her insistence on his constant presence at court.... It also helps to explain his separation from his wife." The Spanish ambassador, Gómez Suárez de Figueroa y Córdoba, 1st Duke of Feria, was one of those who spread these rumours. He wrote to King Philip II: "During the last few days Lord Robert has come so much into favour that he does what he likes with affairs and it is even said that her Majesty visits him in his chamber day and night. People talk of this so freely that they go so far as to say that his wife has a malady in one of her breasts and that the Queen is only waiting for her to die so she can marry Lord Robert."

On this day in 1810 Elizabeth Stevenson, the second surviving child of William Stevenson (1770-1829 and his first wife, Elizabeth Holland Stevenson (1771–1811), was born in Lindsey Row (now Cheyne Walk). Her mother, worn out by giving birth to eight children, of whom only two survived, died thirteen months later. Elizabeth's father was a Unitarian but had given up preaching to become the Keeper of the Treasury Records.

Unable to raise her himself, Stevenson sent Elizabeth to live with her aunt Hannah Lamb, who lived in Knutsford, Cheshire. Her aunt was legally separated from her husband, who had been declared insane. Hannah's own daughter, Marianne, was disabled and died in 1812, aged twenty-one. In 1814 her father married Catherine Thomson. They had two more children but Elizabeth stayed with his aunt, visiting her father and stepmother rarely. She was "very, very unhappy" on such visits, she later wrote, adding that were it not for the comfort of the river, and some local friends, "I think my child's heart would have broken".

Her biographer, Jenny Uglow, has argued: "Elizabeth Stevenson was educated at home, by her aunts and occasional outside tutors, and at the Sunday school of Brook Street Chapel, until 1821. From her family and the chapel she imbibed the tenets of Unitarianism, which rejected as unknowable mystical doctrines such as the Trinity and the divinity of Christ, and placed great stress on human rather than divine responsibility for society. The church emphasized freedom of thought and rationality, believing in social progress aided by scientific discovery. But it also recognized the existence of suffering and oppression, and called on its adherents to speak out against them." At eleven Elizabeth was sent away to a school at Barford, Warwickshire. In May 1824, she attended Avonbank School in Stratford upon Avon, that had been partly funded by a loan from Josiah Wedgwood.

Elizabeth's brother John Stevenson had joined the merchant navy in 1820. His letters stimulated her imagination and in 1827 he encouraged her to write stories. The following year he disappeared on a voyage to India. he news devastated her father and he went into a deep depression. Elizabeth now returned to her father's household in London where she nursed him until his death on 22nd March 1829. She spent the next two years at the home of the Revd William Turner, a relation and a Unitarian minister of Hanover Chapel, Newcastle upon Tyne. Turner was a tireless campaigner for social causes: the emancipation of Catholics and Jews, the abolition of the slave trade, and the support of charity and Sunday schools. He was to have a lasting influence on her political views.

On a visit to Turner's daughter, who lived in Manchester, Elizabeth met William Gaskell, a minister at their local Unitarian chapel. They quickly developed a close friendship and were married on 30th August, 1832. The author of Gaskell: A Habit of Stories (1993) has argued: "They shared a faith and a love of literature and music but often seemed a contrast in appearance and temperament. While Elizabeth was of medium height, tending to plumpness (especially in later life), with an open smile, a constant flow of talk, and a distinct romantic streak, William was extremely tall and thin and apparently austere, with a dry sense of humour and an infinite capacity for hard work. Yet the marriage appears to have been extremely close, despite Elizabeth's many absences from home in later years."

In July 1833 Gaskell's first child, a daughter, was born dead. Her first surviving daughter, Marianne, was born on 12th September 1834 and her daughter's first years are recorded in Gaskell's diary: "She will talk before she walks I think. She can say pretty plainly papa, dark, stir, ship, lamp, book, tea, sweep." Another daughter, Margaret Emily, was born on 5th February 1837.

Gaskell's poem, "Sketches among the Poor", appeared in The Blackwood Magazine in 1837. Her friends encouraged her to do more writing but she felt that she needed to concentrate on caring for her children. She later wrote: "When I had little children I do not think I could have written stories because I should have become too much absorbed in my fictitious people to attend to my real ones... everyone who tries to write stories must become absorbed in them (fictitious though they be) if they are to interest their readers."

Gaskell's next child was born dead. She gave birth to Florence Elizabeth on 7th October 1842. The family now moved to a larger house at 121 Upper Rumford Street, Manchester. On 23rd October 1844 came the birth of the Gaskells' son William, but at ten months later he died of scarlet fever. After this Elizabeth sank into a deep depression which did not really end until her last daughter, Julia Bradford was born in 1846. During this period the Gaskells became friends with the social reformers, Samuel Bamford and James Martineau.

Elizabeth Gaskell was kept busy with the duties of being a minister's wife. She became a member of the District Provident Society, and helped distribute soup tickets, food, and clothing for the poor. Most of William Gaskell's parishioners were textile workers and Elizabeth was deeply shocked by the poverty she witnessed in Manchester. Elizabeth, like her husband, became involved in various charity work in the city. She now considered herself past having anymore children started writing a novel that attempted to illustrate the problems faced by people living in industrial towns and cities. Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life was published in 1848 by Chapman and Hall.

With its casts of working-class characters and its attempt to address key social issues such as urban poverty, Chartism and the emerging trade union movement, Gaskell's novel shocked Victorian society. The Manchester Guardian accused Gaskell of unfairly criticising the employers and The Edinburgh Review denounced her ignorance of economics. However, it was greatly admired by other writers such as Charles Dickens, William Thackeray, John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle. The social reformer, Charles Kingsley, argued in Fraser's Magazine (April 1849), that the novel should be read by the educated classes: "Do they want to know why poor men, kind and sympathising as women to each other, learn to hate law and order, Queen, Lords and Commons, country-party and corn law leagues, all alike - to hate the rich in short? then let them read Mary Barton."

Claire Tomalin has pointed out: "With no more education than any other nice girl born in 1810; with marriage at twenty-one, and seven pregnancies thereafter; with all the domestic and social duties of the wife of a Unitarian minister, and the care and upbringing of her children; not to mention a taste for travel - prison visiting and humanitarian work among the poor - a social life as exuberant as that of Dickens and a circle of friends as large - with all this, still, at the age of thirty-six she became an enormously successful and respected writer in a hugely competitive and brilliant field."

In February 1850, Charles Dickens decided to join forces with his publisher, Bradbury & Evans, and his friend, John Forster, to publish the journal, Household Words. Dickens became editor and William Wills, a journalist he worked with on the Daily News, became his assistant. Dickens planned to serialise his new novels in the journal. He also wanted to promote the work of like-minded writers. The first person he contacted was Elizabeth Gaskell. Dickens had been very impressed with her first novel, Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life (1848) and offered to take her future work. She sent him Lizzie Leigh , a story about a Manchester prostitute, which appeared in the first issue, on 30th March 1850. Dickens also published her stories The Well of Pen Morfa and The Heart of John Middleton .

In August 1850 Elizabeth Gaskell met Charlotte Brontë at the summer home of James Kay-Shuttleworth. The two women became friends and took a keen interest in her children. She later recalled that Gaskell was "a woman of whose conversation and company I should not soon tire. She seems to me kind, clever, animated and unaffected". Gaskell also got to know Florence Nightingale. She admired her sense of duty but found her manner difficult: "She has no friend - and wants none. She stands perfectly alone, half-way between God and His creatures".

Elizabeth Gaskell continued to publish stories in Household Words including "Traits and Stories of the Huguenots", "Morton Hall", "My French Master", "The Squire's Story", "Company Manners", "An Accursed Race", "Half a Lifetime Ago", "The Poor Clare", "My Lady Ludlow", "The Sin of a Father and The Manchester Marriage". She also produced a series of stories that were published between 13th December 1851 and 21st May 1853, that eventually became the novel, Cranford. Her biographer, Jenny Uglow has suggested that the Cranford stories "make the dangerous safe, touching the tenderest spots of memory and bringing the single, the odd and the wanderer into the circle of family and community."

During this period Gaskell visited Charles Dickens at his home: "We were shown into Mr. Dickens' study... where he writes all his books... There are books all around, up to the ceiling, and down to the ground... after dinner ... quantities of other people came in. We were by this time in the drawing-room, which is not nearly so pretty or so home-like as the study... We heard some beautiful music... I kept trying to learn people's faces off by heart, that I might remember them; but it was rather confusing there were so very many. There were some nice little Dickens' children in the room, who were so polite, and well-trained."

Gaskell also began work on a new novel. Ruth (1853) caused even more uproar than Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life. As the author of Gaskell: A Habit of Stories has explained: "Ruth tells the story of a fifteen-year-old seamstress who is seduced and has an illegitimate son. Taken in by a Unitarian minister, Mr Benson, she is passed off as a widow, making a new life until she is exposed and publicly denounced, before finally ‘redeeming’ herself as a nurse in a fever epidemic. A brave attack on current hypocrisy, the novel was attacked not only for the sexual theme but because of Benson's ‘lie’; a copy was even burnt by members of William Gaskell's own congregation." Elizabeth Barrett Browning was one of those who condemned the heroine's death as authorial cowardice. "I am grateful to you as a woman for having treated such a subject. Was it quite impossible but that your Ruth should die?"

Gaskell's next novel, North and South (1855), also appeared in Household Words (2nd September 1854 to 27 January 1855). The book deals with the relationship between Margaret Hale and John Thornton, who ran a textile mill. It has been suggested that Gaskell was attempting to provide a more sympathetic portrait of factory owners. It is probably significant that she had become friendly with social reformer, Robert Hyde Greg, who owned Quarry Bank Mill.

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990) has pointed out: "Mrs Gaskell's North and South, which was proving too long and too unwieldy for serial publication. Mrs Gaskell herself was also somewhat difficult, particularly in her inability or slowness to cut her text as Dickens desired; nothing irritated him more than unprofessional behaviour, especially in novelists whom he knew to be inferior to himself, and although he kept his own communications with Mrs Gaskell relatively courteous he was far from flattering about her to his deputy." Gaskell was also often late in delivering her manuscript. Dickens commented to William Henry Wills that if he was her husband, he would feel compelled to "beat her". Dickens eventually edited the serial and she regarded the abrupt ending of the serial version as "mutilated... like a pantomime figure with a great large head and a very small trunk".

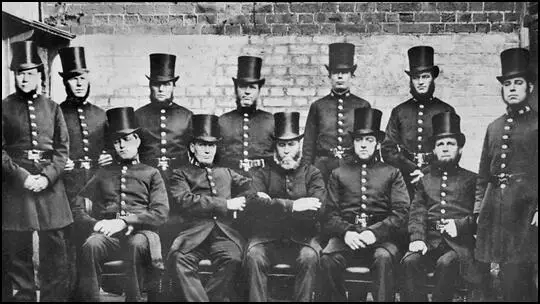

On this day in 1829 the Metropolitan Police was founded by a bill introduced by Sir Robert Peel. For a long time politicians had been concerned about the problems of law and order in London. As a result of this reform, the new metropolitan police force became known as "Peelers" or "Bobbies".

On this day in 1886 Olive Wharry, the daughter of Clara Vickers (1854-1910) and Dr Oliver Robert Wharry (1853-1935) was born in London. On her father's retirement, the family moved to Devon and she later studied at the School of Art in Exeter. In 1906 she travelled around the world with her mother and father.

Wharry became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage and joined the Church League for Women's Suffrage and Women's Social and Political Union in 1909. Wharry justified joining a militant organisation in a statement published in Votes for Women: "How can you expect women to obey laws which they have had no hand in making? Women are classed with imbeciles, aliens, and criminals, and are allowed the rights of citizenship. Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men. For years women have worked quietly and constitutionally, and it is only because constitutional methods have failed that we have adopted militant methods as the only possible means of getting the vote."

On 4th March, 1912, Wharry took part in a window-breaking demonstration. This time the target was government offices in Whitehall. Wharry was one of the 200 suffragettes were arrested and jailed for taking part in the demonstration. She was found guilty of breaking windows worth £195 and was sentenced to six months in prison. As Holloway Prison was full she was sent to Winson Green Prison in Birmingham. Wharry took part in a hunger strike and was released in July. According to the prison doctor, Wharry was "mentally unstable". However, Elizabeth Crawford argued that "Olive Wharry's prison notebook contains no hint of insanity. It is full of delightful drawings of prison life, along with poems, satirical and amusing."

In July 1912, Christabel Pankhurst began organizing a secret arson campaign. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "When the policy was fully underway, certain officials of the Union were given, as their main work, the task of advising incendiaries, and arranging for the supply of such inflammable material, house-breaking tools and other matters as they might require. Women, most of them very young, toiled through the night across unfamiliar country, carrying heavy cases of petrol and paraffin. Sometimes they failed, sometimes succeeded in setting fire to an untenanted building - all the better if it were the residence of a notability - or a church, or other place of historic interest."

The WSPU used a secret group called Young Hot Bloods to carry out these acts. No married women were eligible for membership. The existence of the group remained a closely guarded secret until May 1913, when it was uncovered as a result of a conspiracy trial of eight members of the suffragette leadership, including Flora Drummond, Annie Kenney and Rachel Barrett. During the trial, Barrett said: "When we hear of a bomb being thrown we say 'Thank God for that'. If we have any qualms of conscience, it is not because of things that happen, but because of things that have been left undone."

Olive Wharry was one of the first people to join this group. Lilian Lenton, a fellow member of the WSPU commented: "Well, I was at the Suffragette Headquarters and announced that I didn't want to break any more windows but I did want to burn some buildings, and I was told that a girl named Olive Wharry had just been in saying the same thing, so we two met, and the real serious fires in this country started and thereafter I was in and out of prison – six times I think it was – and whenever I was out of prison my object was to burn two buildings a week."

It has speculated that other members of the group included Helen Craggs, Olive Hockin, Kitty Marion, Mary Richardson, Miriam Pratt, Norah Smyth, Clara Giveen, Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks. It would seem that Helen Craggs was the first to carry out an act of arson. On 13th July 1912 Craggs and another woman were found by P.C. Godden at one o'clock in the morning outside the country home of the colonial secretary Lewis Harcourt. He went towards them and asked them what they were doing. Craggs, said they were looking round the house. The policeman said, "This is not a very nice time for looking round a house. How did you come here? Where do you come from?" Craggs said that they had been camping in the neighbourhood. The police-constable said he had not seen any encampment. She then said they had arrived by the river. Godden seized Miss Craggs and arrested her, and she was taken into custody.

Lilian Lenton explained: "Well, the object was to create an absolutely impossible condition of affairs in the country, to prove that it was impossible to govern without the consent of the governed. A few young men were very anxious to help us. But these young men only seemed to have one idea, and that was bombs. Now I don't like bombs. After all, the rule was that we must risk no-one's lives but our own, and if you take a bomb somewhere, however great the precautions, you can't be one hundred percent sure."

Olive Wharry said that she was inspired by something Charles Hobhouse, Liberal Party, MP for Bristol East, and Postmaster General in the government, said on the subject of women's suffrage at a meeting of the National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage. Hobhouse claimed that women did not feel as strongly as men did on this issue in the 19th century. For example, campaigners had set fire to Nottingham Castle, the home of George Finch-Hatton, 5th Earl of Nottingham, who had opposed the 1832 Reform Act. "In the case of the suffrage demand there has not been the kind of popular sentimental uprising which accounted for the arson and violence of earlier suffrage reforms."

Wharry argued: "Cabinet Ministers have constantly broken their pledges, and therefore the women have revolted. A hundred of thousand pounds' worth of damage was done by men at Bristol who demanded votes, and Mr Hobhouse taunted us with not forcing our demands in a similar way. Our demands have been ridiculed in the past, and therefore we are adopting militant tactics. It is not Mrs Pankhurst who has been inciting, but the Cabinet Ministers. We do not want to go any further, but we must show the Government we mean business."

Wharry joined forces with Lilian Lenton and embarked on a series of terrorist acts. She was arrested on 19th February 1913, soon after setting fire to the tea pavilion in Kew Gardens. In court it was reported: "The constables gave chase, and just before they caught them each of the women who had separated was seen to throw away a portmanteau. At the station the women gave the names of Lilian Lenton and Olive Wharry. In one of the bags which the women threw away were found a hammer, a saw, a bundle to tow, strongly redolent of paraffin and some paper smelling strongly of tar. The other bag was empty, but it had evidently contained inflammables."

At her first appearance before the Richmond Magistrates, Olive Wharry created a sensation by throwing a book and some papers at the Chairman. According to one newspaper at her trial she appeared "a prepossessing young woman, who wore a large buttonhole of violets and primroses." In his summing up the judge commented: "that not very long ago it would have been unthinkable that a well-educated, well-bred young woman could have committed such a crime as that. Unfortunately women as a class had forfeited any presumption in their favour of that kind. They knew that well-educated well-bred young women had committed these crimes, and accordingly it was impossible to approach the case from the standpoint from which they would have approached it a few years ago."

On 7th March 1913 she was found guilty and it was reported by the Daily Mirror that "Wharry laughed when sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment." Wharry made a statement in court where she attempted to explain her actions: "I deny that this court has any jurisdiction over me. A man has the right to be tried by his peers, and so, too, a woman should be tried by women. How can you expect women to obey laws which they have had no hand in making? Women are classed with imbeciles, aliens, and criminals, and are allowed the rights of citizenship. Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men… I am standing for a great principle and morally I am not guilty, though the jury have condemned me, therefore I shall hunger-strike."

It was claimed in court that the tea pavilion "was absolutely destroyed, and a heavy pecuniary loss has thrown upon the two ladies who held the refreshment contract". It was estimated that the loss suffered amounted to £400. It was reported on 26th April that Dr Oliver Robert Wharry was involved in a scuffle when the two solicitors' clerks, employed by the women with the refreshment contract, tried to serve a writ on his daughter. Wharry responded that "she was sorry that the contents of the building was the property of two ladies, she did not know this at the time, but would say to them that this was war, and in a war non-combatants had to suffer."

Olive Wharry went on hunger-strike and Dr Maurice Craig reported to the Home Office that she was "a very frail person, with a very defective circulation... her hands are cold and very blue; her pupils are widely dilated". According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She was released on 8th April after having been on hunger strike for 32 days, apparently without the prison authorities noticing. His usual weight was 7st 11lbs; when released she weighed 5st 9lbs."

As soon as she was strong enough she began taking part in WSPU demonstrations. In May 1914 she was arrested while taking place in a deputation to King George V. The following month she was tried at Carnarvon after breaking windows at Criccieth during a meeting being held by David Lloyd George. Now using the name Phyllis North, she was sentenced to three months in Holloway Prison where she was kept in solitary confinement. Once again she went on hunger strike.

The British government declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Two days later, Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS declared that the organization was suspending all political activity until the conflict was over. Fawcett supported the war effort but she refused to become involved in persuading young men to join the armed forces. The WSPU took a different view to the war. It was a spent force with very few active members. According to Martin Pugh, the WSPU were aware "that their campaign had been no more successful in winning the vote than that of the non-militants whom they so freely derided".

The WSPU carried out secret negotiations with the government and on the 10th August the government announced it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities and help the war effort. Christabel Pankhurst, arrived back in England after living in exile in Paris. She told the press: "I feel that my duty lies in England now, and I have come back. The British citizenship for which we suffragettes have been fighting is now in jeopardy."

After receiving a £2,000 grant from the government, the WSPU organised a demonstration in London. Members carried banners with slogans such as "We Demand the Right to Serve", "For Men Must Fight and Women Must Work" and "Let None Be Kaiser's Cat's Paws". At the meeting, attended by 30,000 people, Emmeline Pankhurst called on trade unions to let women work in those industries traditionally dominated by men. She told the audience: "What would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!".

As part of this deal Olive Wharry was released into the care of Flora Murray on 10th August, 1914. Wharry told the Aberdeen Evening Gazette that she was a "physical wreck". Her eyes were "sunken", her face was pale, her tongue was "blistered and coated" and she spoke with "much difficulty and pain", Wharry had eaten no food and only taken a few drops of water, and felt "rather nervous, and not in a fit condition to tell you everything".

Olive returned to the family home in Holsworthy in North Devon. Olive resumed her art career and exhibited some etchings in an exhibition of work by Devon artists at Exeter Museum in 1917. Olive took an active life in the parish and is reported as taking part in Amateur Dramatics and giving lectures. Later she became secretary of the Launceston and District Women's Unionist Association.

Olive Wharry died in Torquay on 2nd October 1947.

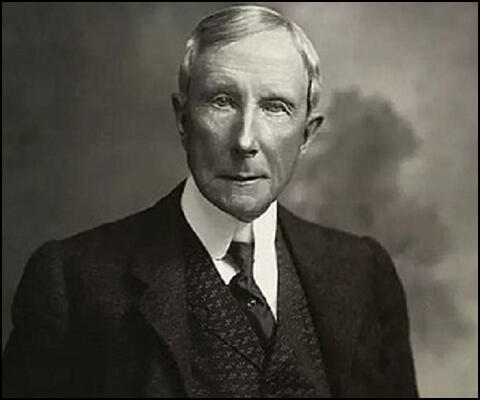

On this day in 1916 American oil tycoon John D. Rockefeller becomes the world's first billionaire. In 1862 Rockefeller established Standard Oil. In November 1902, Ira Tarbell, one of the leading muckraking journalists in the United States, began a series of articles in McClure's Magazine on how Rockefeller had achieved a monopoly in refining, transporting and marketing oil. This material was eventually published as a book, History of the Standard Oil Company (1904). The various press campaigns against Rockefeller had turned him into one of America's most hated men. A devout Baptist, Rockefeller began giving his money away. He set up the Rockefeller Foundation to "promote the well-being of mankind". Over the next few years Rockefeller gave over $500 million in aid of medical research, universities and Baptist churches. He was also a major supplier of funds to organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League that was involved in the campaign for prohibition. By the time that he died died on 23rd My, 1937, John D. Rockefeller had become a popular national figure.

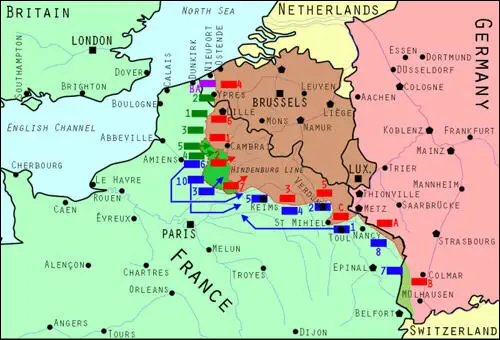

On this day in 1918 Allied forces score a decisive breakthrough of Hindenburg Line. In August, 1916, Paul von Hindenburg became Chief of Staff of the German Army. Hindenburg and his quartermaster general, Erich von Ludendorff, decided to build a system of German defence fortifications behind the northern and central sectors of the Western Front. Constructed between the northern coast and Verdun, each sector had its own system of mutually supporting strongpoints backed up with barbed wire, trenchworks and firepower. After the breakthrough the Allied forces were able to gain complete control of these defences. When this happened, the Third Supreme Command realised that Germany was beaten and handed over power to Max von Baden and the Reichstag.

On this day in 1935 Winifred Holtby died. Vera Brittain was Winifred's literary executor, and was determined to make sure South Riding was published. However, as Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "The major obstacle she faced was the indomitable figure of Holtby's mother, Alice, the first woman alderman of the East Riding. She feared that her daughter's depiction of local government, allied to the vein of satire and puckish mischief familiar from her earlier books, might expose her own job to criticism and ridicule... Alice Holtby remained obdurate in her opposition to the book's publication, forcing Brittain to adopt a strategy of mild subterfuge, negotiating the uncorrected typescript through probate in order to have the novel ready for publication by Collins in the spring of 1936."

Alice Holtby immediately resigned from the East Riding County Council when South Riding was published. It received excellent reviews. One critic claimed: "The most public-spirited novel of her generation." The novel was adapted for the cinema in 1938 starring Edna Best as Sarah Burton, Ralph Richardson as Robert Carne and Edmund Gwenn as Alfred Huggins.

Vera Brittain subsequently wrote about her relationship with Winifred Holtby in her book Testament of Friendship (1940). It was adapted for television by Yorkshire Television in 1974, starring Dorothy Tutin as Sarah Burton, Nigel Davenport as Robert Carne and Judi Bowker as Midge Carne. An adaptation by Andrew Davies, starring Anna Maxwell Martin, David Morrissey, Peter Firth, Penelope Wilton, Douglas Henshall and John Henshaw appeared on BBC in 2011.

Winifred Holtby, the youngest daughter of David Holtby, a prosperous Yorkshire farmer, was born in Rudston, on 23rd June, 1898. Her mother, Alice Winn (1858-1939), was the first alderwoman in Yorkshire.

Holtby attended Queen Margaret's School (1909–16) in Scarborough (1909–16). After a year as a probationer nurse in a London nursing home, she went up to Somerville College in October 1917. Hotby's boyfriend, Harry Pearson, joined the British Army and served on the Western Front during the First World War. She later recalled: "I was sixteen when the war started. The first thing it made me do was fall in love. Brevity of life makes passion more insistent. The youngest and fittest in uniform. The erotic attraction of death."

Winifred Holtby added that: "He (Pearson) told me about all the enormities he had seen at the front - the mouthless mangled faces, the human ribs whence rats would steal, the frenzied tortured horses, with leg or quarter rent away, still living; the rotted farms, the dazed and hopeless peasants; his innumerable suffering comrades; the desert of no-man's-land; and all the thunder and moaning of war; and the reek and freezing of war; and the driving - the callous, perpetual driving by some great force which shovelled warm human hearts and bodies, warm human hopes, by the million into the furnace." Despite these stories Holtby left university in 1918 and joined the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, and served in France. She later recalled that she had: "(a) The desire to suffer and to die - especially when suffering is associated with glory. (b) Fear of immunity from danger when our friends are suffering."

In 1919 she returned to Oxford University where she met Vera Brittain. Her new friend explained in her autobiography, Testament of Youth (1933): "I was staring gloomily at the Oxford engravings and photographs graphs of the Dolomites which clustered together so companionably upon the Dean's study wall, when Winifred Holtby burst suddenly in upon this morose atmosphere of ruminant lethargy. Superbly tall, and vigorous as the young Diana with her long straight limbs and her golden hair, her vitality smote with the effect of a blow upon my jaded nerves. Only too well aware that I had lost that youth and energy for ever, I found myself furiously resenting its possessor. Obstinately disregarding the strong-featured, sensitive face and the eager, shining blue eyes, I felt quite triumphant because - having returned from France less than a month before - she didn't appear to have read any of the books which the Dean had suggested as indispensable introductions to our Period."

Winifred and Vera graduated together in 1921 and they moved to London where they shared a flat in Doughty Street. They hoped to establish themselves as writers. Vera's first two novels, The Dark Tide (1923) and Not Without Honour (1925) sold badly and were ignored by the critics. However, Winifred had more success with Anderby Wold (1923) and The Crowded Street (1924).

In June 1925, Vera married the academic, George Edward Catlin. As Mark Bostridge has pointed out: "When Brittain and Catlin set up home in London after their marriage, Holtby joined them as the third member of the household. Catlin never overcame his resentment at his wife's friendship with the woman Vera described as her second self. He knew, in spite of all the gossip to the contrary, that the Brittain-Holtby relationship had never been a lesbian one, but its closeness still rankled."

Vera and her husband moved to the United States when her husband became a a professor at Cornell University. Vera found it difficult to settle in America and after the birth of her two children, John (1927) and Shirley (1930) she moved back to England where she lived with Winifred Holtby. The two women were extremely close and Vera once described Winifred as her "second self".

Winifred helped to bring up Vera's two children. Shirley Williams, later wrote: "She (Winifred Holtby) was tremendous fun and understood, better than any other grown-up, children's fantasies and fears. We had a dressing-up box full of discarded hats and dresses, scarves and masks and wooden necklaces from Africa. We would perform for our parents the plays Winifred wrote for us... I was a boisterous child, so Winifred, despite her frailty, joined in our rougher games as well. She would crawl around the nursery, balancing cushions on her back, while I rode on top, pretending to direct an elephant from my howdah."

Holtby was a socialist and feminist. She wrote that: "Personally, I am a feminist... because I dislike everything that feminism implies.… I want to be about the work in which my real interests lie... But while injustice is done and opportunity denied to the great majority of women, I shall have to be a feminist." Like her companion, Vera Brittain, Winifred was a pacifist and lectured extensively for the League of Nations Union. Winifred gradually became more critical of the class system and inherited privileges and by the late 1920s was active in the Independent Labour Party.

Winifred's relationship with Vera created a certain amount of gossip. Vera's daughter, Shirley Williams, argued: "Some critics and commentators have suggested that their relationship must have been a lesbian one. My mother deeply resented this. She felt that it was inspired by a subtle anti-feminism to the effect that women could never be real friends unless there was a sexual motivation, while the friendships of men had been celebrated in literature from classical times. My mother was instinctively heterosexual. But as a famous woman author holding progressive opinions, she became an icon to feminists and in particular to lesbian feminists." However, Vera's husband, George Edward Catlin, did not approve of the relationship. He wrote later: "You preferred her to me. It humiliated me and ate me up."

In 1926 Winifred Holtby became one of the directors of the feminist journal, Time and Tide. In an article published in August of that year she wrote: "Hitherto, society has drawn one prime division between two sections of people, the line of sex-differentiation, with men above and women below. The Old Feminists believe that the conception of this line, and the attempt to preserve it by political and economic laws and social traditions not only checks the development of the woman's personality, but prevents her from making that contribution to the common good which is the privilege and the obligation of every human being. While the inequality exists, while injustice is done and opportunities denied to the great majority of women, I shall have to be a feminist, and an Old Feminist, with the motto Equality First. And I shan't be happy till I get it."

Holtby took a keen interests in the struggle for equal rights in South Africa. She criticised General Jan Smuts when he failed to stop the introduction of racist legislation. Holtby argued that the reason for this was that "because for Smuts and his contemporaries, the human horizon does not yet extend to coloured races, as, for Fox and his 18th-century contemporaries, it did not extend to English women."

Vera's daughter, Shirley Williams, enjoyed living with Winifred: "What I remember above all about Winifred Holtby is her radiance. She was a ray of sunshine in the intense and preoccupied atmosphere of home life in my early years.... She was Viking-like in appearance, impressively statuesque with bright blue eyes and very pale flaxen hair."

Winifred Holtby published another novel, The Land of Green Ginger, in 1927. However, as Alan Bishop has pointed out: "Holtby's lively, stylish, witty articles and reviews soon gained her a high reputation as a journalist. She wrote for The Manchester Guardian and a regular weekly article for the trade union magazine, The Schoolmistress. Books publishing during this period included, Poor Caroline (1931), a critical study of Virginia Woolf (1932), Mandoa, Mandoa! (1933) and a volume of short stories, Truth is Not Sober (1934).

In the early 1930s Winifred began to suffer with high-blood-pressure, recurrent headaches and bouts of lassitude. According to Shirley Williams: "She was subject to bouts of serious illness, the consequence of a childhood episode of scarlet fever that led to sclerosis of the kidneys". Eventually she was diagnosed as suffering from Bright's Disease. Her doctor told her that she probably only had two years to live. Aware she was dying, Winifred put all her remaining energy into what became her most important book, South Riding.

Vera Brittain later recalled that she asked Harry Pearson to tell "Winifred he loved her and always had; that he'd like to marry her when she was better". She added that on 28th September, 1935: "At about three o'clock Hilda Reid rang up to say that Dr. Obermer had been round to the home and had already put Winifred under morphia; she was now unconscious and would never be permitted to come back to consciousness again. Later I learnt that Dr. Obermer did this because after Harry had been with Winifred she was so happy and excited that he feared a violent convulsion for her, with physical pain and mental anguish; and that he thought it best to let her go out on that moment of happiness, with the cruel realization that what she was hoping could never be fulfilled."

The following day Vera went to visit Winifred at the nursing home at 23 Devonshire Street in Marylebone: "Shortly after six o'clock I realised that she was breathing more shallowly, while her pulse was slower and weaker. After almost a quarter of an hour her pulse, which I was holding, had almost stopped, and her breathing seemed to come from her throat only... It was strange, incredible, after all the years of our friendship and all that we had shared together, to feel her life flickering out under my hand. Suddenly her pulse stopped; she had given two or three deeper breaths and then these ceased and I thought she had stopped breathing too; but after a moment came one final, lingering sigh, and then everything was at an end."

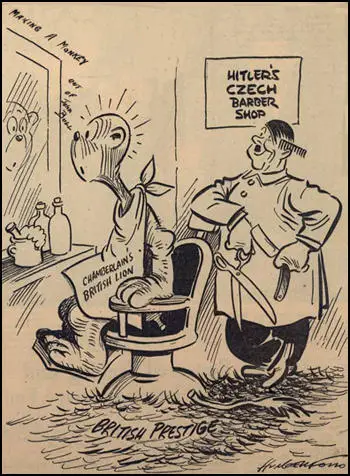

On this day in 1938, Neville Chamberlain, Adolf Hitler, Edouard Daladier and Benito Mussolini discussed the Munich Agreement. Chamberlain and Halifax met Tomas Masaryk, the Czechoslovak minister in London. Masaryk tried to insist that his country should be represented in these talks. However, he was told that Hitler had only agreed to the conference on condition that the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia were excluded. Masaryk replied: "If you have sacrificed my nation to preserve the peace of world, I will be the first to applaud you. But if not, gentlemen, God help your souls."

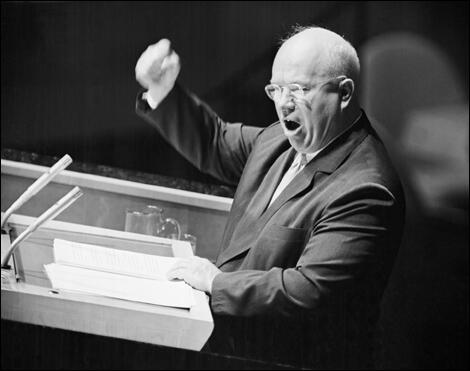

On this day in 1960 Nikita Khrushchev heckled and thumped his desk during a speech by Harold Macmillan, the prime minister, to the UN general assembly.