On this day on 28th November

On the day in 1814 The Times becomes the first newspaper to be produced on a steam-powered printing press. In 1785 John Walter came to the conclusion that a good way of publicizing his logography system was by producing a daily advertising sheet. The first edition of the Daily Universal Register was published on 1st January, 1785. The newspaper was in competition with eight other daily newspapers in London. Like the other newspapers,it included parliamentary reports, foreign news and advertisements. John Walter made it clear in the first edition of the newspaper that he was primarily concerned with advertising revenue: "The Register, in its politics, will be of no party. Due attention should be paid to the interests of trade, which are so greatly promoted by advertisements."

After a couple of years John Walter had discovered that logography was not going to have the impact on the printing industry that he had initially thought when he started the Daily Universal Register . However, he was now convinced he could make a profit from newspapers. Especially when he was able to negotiate a secret deal where he was paid £300 a year to publish stories favourable to the government.

In 1788 John Walter decided to change the name and the style of his newspaper. Walter now started to produce a newspaper that appealed to a larger audience. This included stories of the latest scandals and gossip about famous people in London. Walter called his new paper The Times. One of these stories about the Prince of Wales resulted in Walter being fined £50 and sentenced to two years in Newgate Prison.

In January, 1803 John Walter's son, John Walter II, became the new proprietor of The Times. John Walter II decided he wanted to run a newspaper that was independent of government control. He began employing young journalist who supported political reform including Henry Crabbe Robinson, Charles Lamb, William Hazlitt and Thomas Barnes. The newspaper turned away from government minister's handouts and instead developed its own news-getting organisation.

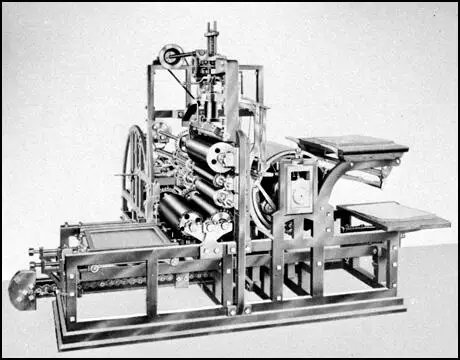

John Walter II also introduced new technology into The Times. In 1814 he installed a steam-powered Koenig printing machine. This increased the speed that newspapers could be printed and by the end of the year, the newspaper was selling over 7,000 copies a day. In the same year that the newspaper obtained their steam-powered printing machine, Thomas Barnes became the new editor of the newspaper. Barnes was a strong advocate on independent reporting. In 1819 he published a several articles written by John Edward Taylor and John Tyas on the Peterloo Massacre.

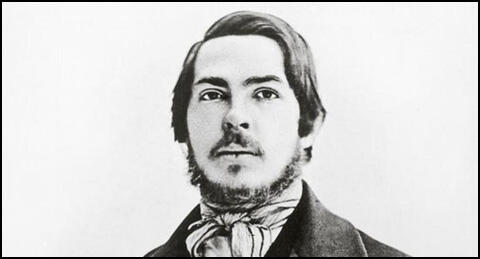

On the day in 1820 Friedrich Engels the eldest son of a successful German industrialist, was born in Barmen, Germany. As a young man his father sent him to England to help manage his cotton-factory in Manchester. Engels was shocked by the poverty in the city and began writing an account that was published as Condition of the Working Class in England (1844). He also made friends with the leaders of the Chartist movement in Britain.

In 1844 Engels began contributing to a radical journal called Franco-German Annalsthat was being edited by Karl Marx in Paris. Later that year Engels met Marx and the two men became close friends. Engels shared Marx's views on capitalism and after their first meeting he wrote that there was virtually "complete agreement in all theoretical fields". Marx and Engels decided to work together. It was a good partnership, whereas Marx was at his best when dealing with difficult abstract concepts, Engels had the ability to write for a mass audience.

While working on their first article together, The Holy Family, the Prussian authorities put pressure on the French government to expel Karl Marx from the country. On 25th January 1845, Marx received an order deporting him from France. Marx and Engels decided to move to Belgium, a country that permitted greater freedom of expression than any other European state.

Friedrich Engels helped to financially support Marx and his family. Engels gave Marx the royalties of his book, Condition of the Working Class in England and arranged for other sympathizers to make donations. This enabled Marx the time to study and develop his economic and political theories.

In July 1845 Engels took Karl Marx to England. They spent most of the time consulting books in Manchester Library. During their six weeks in England, Engels introduced Marx to several of the Chartist leaders including George Julian Harney.

Engels and Marx returned to Brussels and in January 1846 they set up a Communist Correspondence Committee. The plan was to try and link together socialist leaders living in different parts of Europe. Influenced by Marx's ideas, socialists in England held a conference in London where they formed a new organisation called the Communist League. Engels attended as a delegate and took part in developing a strategy of action.

Engels returned to England in December 1847 where he attended a meeting of the Communist League' Central Committee in London. At the meeting it was decided that the aims of the organisation was "the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the domination of the proletariat, the abolition of the old bourgeois society based on class antagonisms, and the establishment of a new society without classes and without private property".

Engels and Marx began writing a pamphlet together. Based on a first draft produced by Engels called the Principles of Communism, Marx finished the 12,000 word pamphlet in six weeks. Unlike most of Marx's work, it was an accessible account of communist ideology. Written for a mass audience, The Communist Manifesto summarised the forthcoming revolution and the nature of the communist society that would be established by the proletariat.

The Communist Manifesto begins with the assertion, "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." Marx and Engels argued that if you are to understand human history you must not see it as the story of great individuals or the conflict between states. Instead, you must see it as the story of social classes and their struggles with each other. Marx and Engels explained that social classes had changed over time but in the 19th century the most important classes were the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. By the term bourgeoisie Marx and Engels meant the owners of the factories and the raw materials which are processed in them. The proletariat, on the other hand, own very little and are forced to sell their labour to the capitalists.

Marx and Engels believed that these two classes are not merely different from each other, but also have different interests. They went on to argue that the conflict between these two classes would eventually lead to revolution and the triumph of the proletariat. With the disappearance of the bourgeoisie as a class, there would no longer be a class society. As Engels later wrote, "The state is not abolished, it withers away."

The The Communist Manifesto was published in February, 1848. The following month, the government expelled Engels and Marx from Belgium. Marx and Engels visited Paris before moving to Cologne where they founded a radical newspaper, New Rhenish Gazette. The men hoped to use the newspaper to encourage the revolutionary atmosphere that they had witnessed in Paris.

Friedrich Engels helped form an organisation called the Rhineland Democrats. On 25th September, 1848, several of the leaders of the group were arrested. Engels managed to escape but was forced to leave the country. Karl Marx continued to publish the New Rhenish Gazette until he was expelled in May, 1849.

Engels and Marx now moved to London. The Prussian authorities applied pressure on the British government to expel the two men but the Prime Minister, John Russell, held liberal views on freedom of expression and refused. With only the money that Engels could raise, the Marx family lived in extreme poverty.

In order to help supply Karl Marx with an income, Engels returned to work for his father in Germany. The two kept in constant contact and over the next twenty years they wrote to each other on average once every two days. Friedrich Engels sent postal orders or £1 or £5 notes, cut in half and sent in separate envelopes. In this way the Marx family was able to survive.

Other books published by Engels include The Peasant War in Germany (1850), Anti-Dühring (1878) and the Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884) .

Karl Marx died in London in March, 1883. Engels devoted the rest of his life to editing and translating Marx's writings. This included the second volume of Das Kapital (1885). Engels then used Marx's notes to write the third volume that was published in 1894. Friedrich Engels died in London on 5th August 1895

On the day in 1905 Arthur Griffith established Sinn Féin as a political party. Griffith founded a new Irish Republican group called (Ourselves Alone) in 1902. Originally a cultural revival movement it gradually became a political movement and by 1916 James Connolly had emerged as one of the key figures in the struggle for Irish independence. Connolly led the Easter Rising in 1916 and as a result sixteen of the leaders of Sinn Fein were executed.

Sinn Fein put up 102 candidates in the 1918 General Election and won 497,107 votes. The seventy three elected members of parliament did not attend the House of Commons and instead established their own independent parliament in Dublin.

On the day in 1919 Nancy Astor is elected as a Member of the Parliament. Nancy Langhorne, the eighth child in a family of eleven, was born in Danville, Virginia, on 19th May 1879. Her father, Chiswell Dabney Langhorne (1843-1919), was a wealthy businessman who had made a fortune in railway development. Her mother, Nancy Witcher Keene (1848–1903), married when she was sixteen and worked as a nurse in the last days of the American Civil War.

Nancy's biographer, Martin Pugh, has pointed out: "Nancy Langhorne received a scanty education at a school in Richmond and later at Miss Brown's Academy for Young Ladies, a finishing school in New York. A small, trim figure with piercing blue eyes, she lacked the good looks of her sister, Irene, an acknowledged southern beauty who was known as Queen Bee in the family. From an early age Nancy used her ready wit, which often deteriorated into mere rudeness, to help her fight for a dominant role in her large and competitive family. She possessed enormous energy, loved sports, and was rather a tomboy. But her outward aggression hid considerable insecurity, and throughout her life she found difficulty in establishing close relationships. The combination of her southern protestant upbringing and her personal insecurity made her appear puritanical and censorious; in particular she had a lifelong aversion for alcoholic drink and a rooted fear of physical relationships."

In 1897 Nancy married Robert Gould Shaw. She was revolted by his heavy drinking and his sexual demands. Though they had a son, Bobbie, they were separated in 1901 and divorced in 1903. The following year she moved to England where she met and married the immensely wealthy Waldorf Astor. She later commented: "I married beneath me, all women do." The couple moved into Cliveden, a large estate in Buckinghamshire on the River Thames. They also had a home in St. James's Square.

Waldorf Astor was a member of the Conservative Party and represented the Sutton division of Plymouth in the House of Commons. On the death of his father in 1919, Astor became a member of the House of Lords. Nancy now became the party's candidate in the resulting by-election. Oswald Mosley was one of those who campaigned for her in the election: "She was less shy than any woman - or any man - one has ever known. She'd address the audience and then she'd go across to some old woman scowling in a neighbouring doorway, who simply hated her, take both her hands and kiss her on the cheek or something of that sort. She was absolutely unabashed by any situation. Great effrontery but also, of course, enormous charm. People were usually overcome by it. She was much better when she was interrupted. She must have prayed for hecklers and interrupters. She certainly got a lot."

Nancy Astor beat the Liberal Party candidate, Isaac Foot, and on 1st December 1919 became the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons (the first woman to be elected was Constance Markievicz in 1918 but as a member of Sinn Fein had disqualified herself by refusing to take the oath). Markievicz, like many feminists, was highly critical that a woman who had not been part of the suffrage campaign had been elected to parliament. She accused her being a member of the "upper classes" and "out of touch" with the needs of ordinary people. Norah Dacre Fox, one of the leaders of the Women's Social and Political Union pointed out: "the first woman to be elected for an English constituency was an American born citizen, who had no credentials to represent British women in their own parliament save that she had married a British subject." Rachel Strachey said she was "lamentably ignorant of everything she ought to know".

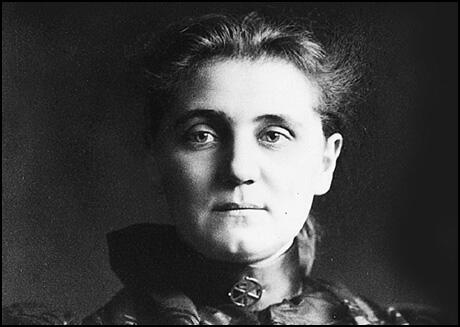

On the day in 1919 Jane Addams defends free speech for radicals. In 1919 Woodrow Wilson appointed A. Mitchell Palmer as his attorney general. Palmer had previously been associated with the progressive wing of the party and had supported women's suffrage and trade union rights. However, once in power, Palmer's views on civil rights changed dramatically and became associated with what was called the Red Scare.

Soon after taking office, a government list of 62 people believed to hold "dangerous, destructive and anarchistic sentiments" was leaked to the press. This list included the names of Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, Oswald Garrison Villard and Charles Beard. It was also revealled that these people had been under government surveillance for many years.

Worried by the revolution that had taken place in Russia, Palmer became convinced that Communist agents were planning to overthrow the American government. His view was reinforced by the discovery of thirty-eight bombs sent to leading politicians and the Italian anarchist who blew himself up outside Palmer's Washington home. Palmer recruited John Edgar Hoover as his special assistant and together they used the Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) to launch a campaign against radicals and left-wing organizations.

A. Mitchell Palmer claimed that Communist agents from Russia were planning to overthrow the American government. On 7th November, 1919, the second anniversary of the Russian Revolution, over 10,000 suspected communists and anarchists were arrested. Palmer and Hoover found no evidence of a proposed revolution but large number of these suspects were held without trial for a long time. The vast majority were eventually released but Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Mollie Steimer, and 245 other people, were deported to Russia.

Jane Addams, who helped to establish Hull House, Women's Trade Union League, National American Women's Suffrage Association, National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People and Woman's Peace Party, spoke out against this legislation. "Hundreds of poor laboring men and women are being thrown into jails and police stations because of their political beliefs. In fact, an attempt is being made to deport an entire political party. These men and women, who in some respects are more American in ideals than the agents of the government who are tracking them down, are thrust into cells so crowded they cannot lie down. And what is it these radicals seek? It is the right of free speech and free thought; nothing more than is guaranteed to them under the Constitution of the United States, but repudiated because of the war. It is a dangerous situation we face at the present time, with the rule of the few overcoming the voice of the many. It is doubly dangerous because we are trying to suppress something upon which our very country was founded - liberty. The cure for the spirit of unrest in this country is conciliation and education - not hysteria. Free speech is the greatest safety valve of our United States. Let us give these people a chance to explain their beliefs and desires. Let us end this suppression and spirit of intolerance which is making of America another autocracy."

On the day in 1924 Winston Churchill refuses to increase taxes on the rich. During the 1924 General Election campaign Churchill argued "I represent uncompromising opposition to the subversive movement of Socialism, and I equally oppose those who are willing to make... compromising bargains with the Socialists." In another speech he insisted that "I am in favour of developing trade within the Empire, but I am not in favour of risking our money on Russia and other foreigners."

Austen Chamberlain advised Stanley Baldwin to put Churchill, a former member of the Liberal Party, in the Cabinet: "If you leave him out, he will be leading a Tory rump in six months' time." Thomas Jones, one of Baldwin's leading advisers, commented: "I would certainly have him inside, not out" and suggested sending him to the Board of Trade or the Colonial Office. Baldwin eventually decided to offer him the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. Churchill replied: "This fulfils my ambition. I still have my father's robes as Chancellor. I shall be proud to serve you in this splendid office."

Churchill had no experience of financial or economic matters when he went to the Treasury in November 1924. He made it clear to Sir Richard Hopkins, the chairman of the Board of Inland Revenue that he had no intention of increasing taxes on the rich: "As the tide of taxation recedes it leaves the millionaires stranded on the peaks of taxation to which they have been carried by the flood... Just as we have seen the millionaire left close to the high water mark and the ordinary Super Tax payer draw cheerfully away from him, so in their turn the whole class of Super Tax payer will be left behind on the beach as the great mass of the Income Tax payers subside into the refreshing waters of the sea."

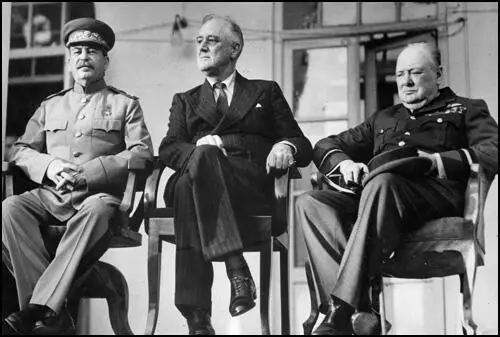

On the day in 1943 Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt meet in Tehran to discuss military strategy and post-war Europe. Ever since the Soviet Union had entered the war, Stalin had been demanding that the Allies open-up a second front in Europe. Churchill and Roosevelt argued that any attempt to land troops in Western Europe would result in heavy casualties. Until the Soviet's victory at Stalingrad in January, 1943, Stalin had feared that without a second front, Germany would defeat them.

Stalin, who always favoured in offensive strategy, believed that there were political, as well as military reasons for the Allies' failure to open up a second front in Europe. Stalin was still highly suspicious of Churchill and Roosevelt and was worried about them signing a peace agreement with Adolf Hitler. The foreign policies of the capitalist countries since the October Revolution had convinced Stalin that their main objective was the destruction of the communist system in the Soviet Union. Stalin was fully aware that if Britain and the USA withdrew from the war, the Red Army would have great difficulty in dealing with Germany on its own.

At Teheran, Joseph Stalin reminded Churchill and Roosevelt of a previous promise of landing troops in Western Europe in 1942. Later they postponed it to the spring of 1943. Stalin complained that it was now November and there was still no sign of an allied invasion of France. After lengthy discussions it was agreed that the Allies would mount a major offensive in the spring of 1944.

From the memoirs published by those who took part in the negotiations in Teheran, it would appear that Stalin dominated the conference. Alan Brook, chief of the British General Staff, was later to say: "I rapidly grew to appreciate the fact that he had a military brain of the very highest calibre. Never once in any of his statements did he make any strategic error, nor did he ever fail to appreciate all the implications of a situation with a quick and unerring eye. In this respect he stood out compared with Roosevelt and Churchill."

The D-Day landings in June, 1944 took the pressure off the Red Army and from that date they made steady progress into territory held by Germany. Country after country fell to Soviet forces. Winston Churchill became concerned about the spread of Soviet power and visited Moscow in October, 1944. Churchill agreed with Joseph Stalin that Rumania and Bulgaria should be under "Soviet influence" but argued that Yugoslavia and Hungary should be shared equally amongst them.

On the day in 1960 Richard Wright, American novelist, died. Wright, the grandson of slaves, was born in Natchez, Mississippi, on 4th September, 1908. His father deserted the family in 1914 and when Richard was ten years old his mother had a paralytic stroke. The family were extremely poor and after a brief formal education he was forced to seek employment in order to support his mother.

He later wrote: "The bleakness of the future affected my will to study. What had I learned so far that would help me to make a living? Nothing. I could be a porter like my father before me, but what else? And the problem of living as a Negro was cold and hard. What was it that made the hate of whites for blacks so steady, seemingly so woven into the texture of things? What kind of life was possible under that hate? How had that hate come to be? Nothing about the problems of Negroes was ever taught in the classrooms at school; and whenever I would raise these questions with the boys, they would either remain silent or turn the subject into a joke."

Wright worked in a series of menial jobs in Memphis. He wanted to continue his education by using the local library but Jim Crow laws prevented this. Wright solved the problem by forging notes to pretend he was collecting the books for a white man. During this period he was particularly impressed by the work of H. L. Mencken, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis.

After passing a civil service examination Wright finds work as a post office clerk. After the Wall Street Crash and the beginning of the Great Depression, Wright lost his job. For a period he found employment with the Negro Burial Society but that came to an end in 1931 and he was forced to go on relief. After several temporary jobs the relief office find him work with the Federal Writers' Project. This enables him to publish his short story, Superstition in the magazine, Abbott's Monthly.

In 1932 Wright began attending meetings of the literary group, the John Reed Club. He later wrote: "The revolutionary words leaped from the page and struck me with tremendous force. My attention was caught by the similarity of the experiences of workers in other lands, by the possibility of uniting scattered but kindred peoples into a whole. It seemed to me that here at last, in the realm of revolutionary expression, Negro experience could find a home, a functioning value and role."

He met several Marxists at the club and later that year joined the American Communist Party. His poems, short-stories and essays are accepted by various left-wing journals including the New Masses, Left Front and International Literature. His poem, Between the World and Me, and a short story, Big Boy Leaves Homes, were both of based on the lynching of a black man that he had witnessed when he was a child.

In May 1937 Richard Wright moved to New York where he became Harlem editor of the Daily Worker and a new literary quarterly, Challenge. The following year, Uncle Tom's Children, a collection of short stories about racism in the United States, was published. In 1940, Bright and Morning Star, was published and Wright announced that all royalties would be used to help to pay the appeal costs of Earl Browder, the general secretary of the American Communist Party, who had been sentenced to four years in prison for misusing a passport.

Wright's novel, Native Son, was accepted by the publishers, Harper, in 1940. The Book of the Month Club selected the novel as its March selection, therefore ensuring large sales and publicity. Over a quarter of a million copies were sold within four weeks, making it the fastest selling Harper novel in twenty years.

Irving Howe argued: "The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever. No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of the old lies. In all its crudeness, melodrama, and claustrophobia of vision, Richard Wright's novel brought out into the open, as no one ever had before, the hatred, fear, and violence that have crippled and may yet destroy our culture."

Native Son is the story of Bigger Thomas, a black ghetto dweller in Chicago, who is hired by a wealthy family as their chauffeur. He is befriended by the family's liberal daughter and her Communist boyfriend. Thomas accidentally kills the daughter and later he murders his girlfriend after she refuses to help him. He is captured and defended by a Marxist lawyer who tries to get him to articulate the harshness of his life that has led to these violent acts. He is unable to do this and and the end he can only affirm that: "What I killed for, I am!" Some critics attacked the novel for what they believed was an excess of hatred and violence. Marxists also criticised the book for placing too much emphasis on individual rebellion, and not enough on class consciousness and group action.

Wright's next book, Twelve Million Black Voices (1941), was a sociological study of the black migration from the rural South to the urban North. an illustrated folk history of American blacks. Wright deliberately used the word black rather than Negro. Wright argued that the word Negro is a white man's word that artificially limits the scope of a black man's life and helps to set it apart from other Americans.

In the book Wright argues that African civilization is a culture that should inspire pride: "We had our own civilization in Africa before we were captured off to this land. You may smile when we call the way of life we lived in Africa 'civilization', but in numerous respects the culture of many of our tribes was equal to that of the lands from which the slave captors came." The book was hardly reviewed in the United States but received favourable reviews in Europe.

By 1944 Wright felt that the American Communist Party was almost as oppressive as capitalism. He left the party and published an article in the Atlantic Monthly, entitled The God That Failed. He remained a Marxist but as he pointed out in his article, "I wanted to be a communist, but my kind of communist". He added: "I knew in my heart that I should never be able to feel and that simple sharpness about life, should never again express such passionate hope, should never again make so total a commitment of faith."

William Patterson claims that Wright left the party after a dispute with Harry Haywood: "Although he was convinced that the political philosophy of Communism was correct, he did not see a book as a political weapon. He thought that the creative genius of a writer should be freed from all restrictions and restraints, especially those of a political nature, and that the writer should write as he pleased. Unfortunately, Harry Haywood, then top organizer on the Southside, did not exhibit the slightest appreciation that he was dealing with a sensitive, immature creative genius with whom it was necessary to exercise great patience. He criticized some of Wright's earlier characters sharply and tried to force him into a mold that was not to his liking. Name-calling resulted and Haywood used his political position to get a vote of censure against Wright, who thereupon resigned from the Party."

Wright's short novel, The Man Who Lived Underground appeared in 1944. It tells the story of a black man who, after being forced by the police to sign a confession to a crime he had not committed, escapes and hides in a sewer. The book influenced his close friend, Ralph Ellison, in the writing of his novel, the Invisible Man.

Wright's powerful autobiography, Black Boy: A Record of Childhood and Youth was published in 1945. After the Second World War, hostility towards writers with left-wing views increased and in 1947 he moved to Paris. He told a friend, that "any black man remaining in the United States after the age of thirty-five was bound to kill, be killed, or go insane." In Paris he joined a group of black writers and artists that included James Baldwin, Chester Himes and Ollie Harrington.

After a spell of inactivity, Richard Wright published two novels, The Outsider (1953) and Savage Holiday (1954). He also travelled to Ghana and wrote an account of his experiences in the book, Black Power (1954). This was followed by a collection of essays, White Man, Listen (1957). The Psychological Reactions of Oppressed People, provided a warning of what might happen if those in power continued to deny human rights to black people. In another essay, The Literature of the Negro in the United States, Wright promoted the work of Phyllis Wheatley, William Du Bois, Claude McKay and Langston Hughes.

Wright's work inspired a generation of black writers. Eldridge Cleaver wrote in Soul on Ice (1968): "Of all black American novelists, and indeed of all American novelists of any hue, Richard Wright reigns supreme for all profound political, economic, and social reference."

Wright's final novel, The Long Dream was published in 1958. Richard Wright died of a heart attack in Paris on 28th November, 1960. There had been no history of heart trouble and rumours circulated that he had been murdered. Wright was himself concerned about the possibility of being killed since being investigated by Joseph McCarthy in 1953. Just before his death Wright had received several mysterious phone calls from people with fictitious names.

On the day in 1990 Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister. Earlier in the month Thatcher was challenged as leader of the Conservative Party. She won the first round of the contest but the majority is not enough to prevent a second round. On 28th November, 1990, Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister and was replaced by John Major. The Daily Telegraph, who supported her throughout her premiership commented: "Margaret Thatcher was the only British prime minister to leave behind a set of ideas about the role of the state which other leaders and nations strove to copy and apply. Monetarism, privatisation, deregulation, small government, lower taxes and free trade - all these features of the modern globalised economy were crucially promoted as a result of the policy prescriptions she employed to reverse Britain’s economic decline." It was a complete failure and we are still living with the consequences of these disastrous policies.