On this day on 28th May

On this day in 1830 resident Andrew Jackson signs the Indian Removal Act The forced removal of Native Americans from their lands started with the state of Georgia. In 1802 the Georgia legislature signed a compact giving the federal government all of her claims to western lands in exchange for the government's pledge to extinguish all Indian titles to land within the state.

The Cherokees had substantial land in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia and Alabama. To protect their land they adopted a written constitution that proclaimed that the Cherokee nation had complete jurisdiction over its own territory. The state of Georgia responded by making it illegal for a Native American to bring a legal action against a white man.

The Seminole tribe had disputes with settlers in Florida. The Creeks were involved in several battles with the federal army in Alabama and Georgia. The Chickisaw and Choctaw tribes also had land disputes with emigrants who had settled in Mississippi.

Andrew Jackson argued that the solution to this problem was to move all these five tribes to Oklahoma. When Andrew Jackson gained power he encouraged Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act. He argued that the legislation would provide land for white invaders, improve security against foreign invaders and encourage the civilization of the Native Americans. In one speech he argued that the measure "will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites; enable them to pursue happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the government and through the influences of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and christian community."

Jackson was re-elected with an overwhelming majority in 1832. He now pursued the policy of removing Native Americans from good farming land. He even refused to accept the decision of the Supreme Court to invalidate Georgia's plan to annex the territory of the Cherokee. This brought Jackson into conflict with Whig leaders such as Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.

The land given to the Native Americans in Oklahoma was known as the Indian Territory. The land was distributed in the following way: Choctaws (6,953,048 acres), Chickisaw (4,707,903 acres) and Cherokees (4,420,068). The tribes were also received money for their former lands: Cherokee ($2,716,979), Creek ($2,275,168), Seminole ($2,070,000), Chickisaw ($1,206,695) and Choctaw ($975,258). Some of these tribes used this money to buy land in Oklahoma and to support the building of schools.

In 1835 some leaders of the Cherokee tribe signed the Treaty of New Echota. This agreement ceded all rights to their traditional lands to the United States. In return the tribe was granted land in the Indian Territory. Although the majority of the Cherokees opposed this agreement they were forced to make the journey by General Winfield Scott and his soldiers. In October 1838 about 15,000 Cherokees began what was later to be known as the Trail of Tears. Most of the Cherokees travelled the 800 mile journey on foot. As a result of serious mistakes made by the Federal agents who guided them to their new land, they suffered from hunger and the cold weather and an estimated 4,000 people died on the journey.

Overall it is believed that about 70,000 Native Americans were forced to migrate from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia, Tennessee and Florida to Oklahoma. During the journey many died as a result of famine and disease.

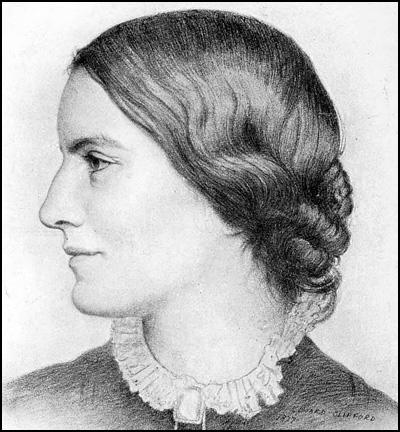

On this day in 1885 Beatrice Webb writes in her diary about Octavia Hill: "Mr Barnett told me much about Octavia Hill. How, when he met her as a young curate just come to London, she had opened the whole world to him. A cultivated mind, susceptible to art, with a deep enthusiasm and faith, and a love of power. This she undoubtedly has and shows it in her age in a despotic temper... I remember her well in the zenith of her fame; some 14 years ago. I remember her dining with us in Prince's Gate, I remember thinking her a sort of ideal of the attraction of woman's power. At that time she was constantly attended by Edward Bond. Alas! for we poor women! Even our strong minds do not save us from tender feelings. Companionship, which meant to him intellectual and moral enlightenment, meant to her "Love". This, one fatal day, she told him. Let us draw the curtain tenderly before that scene and inquire no further. She left England for two years' ill health. She came back a changed woman.... She is still a great force in the world of philanthropic action, and as a great leader of woman's work she assuredly takes the first place. But she might have been more, if she had lived with her peers and accepted her sorrow as a great discipline."

On this day in 1908 Ian Fleming, the second of four sons of Valentine Fleming (1882–1917) and Evelyn Beatrice Ste Croix (1885–1964), was born on 28th May, 1908. His grandfather was Robert Fleming, an extremely wealthy banker. The family lived at Braziers Park, a large house at Ipsden in Oxfordshire.

Ian's father was active in the Conservative Party and in 1910 he became the member of the House of Commons for South Oxfordshire. A fellow member of parliament, Winston Churchill, pointed out that Fleming was "one of those younger Conservatives who easily and naturally combine loyalty to party ties with a broad liberal outlook upon affairs and a total absence of class prejudice... He was a man of thoughtful and tolerant opinions, which were not the less strongly or clearly held because they were not loudly or frequently asserted.... He could not share the extravagant passions with which the rival parties confronted each other. He felt that neither was wholly right in policy and that both were wrong in mood." On the outbreak of the First World War Fleming joined the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars.

Fleming was educated at Durnford Preparatory School and in 1917 he met Ivar Bryce on a beach in Cornwall: "The fortress builders generously invited me to join them, and I discovered that their names were Peter, Ian, Richard and Michael, in that order. The leaders were Ian and Peter, and I gladly carried out their exact and exacting orders. They were natural leaders of men, both of them, as later history was to prove, and it speaks well for them all that there was room for both Peter and Ian in the platoon."

In May 1917 Fleming heard news that his father, Valentine Fleming, had been killed while fighting on the Western Front. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Order. Fleming went to Eton College but as his biographer, Andrew Lycett, has pointed out: "At Eton he showed little academic potential, directing his energies into athletics, becoming victor ludorum two years in succession, and into school journalism."

While at Eton he became a close friend of Ivar Bryce. He purchased a Douglas motorbike and used this vehicle for trips around Windsor. He also took Fleming on the bike to visit the British Empire Exhibition in London. They also published a magazine, The Wyvern , together. Fleming used mother's contacts to persuade Augustus John and Edwin Lutyens, to contribute drawings. The magazine also published a poem by Vita Sackville-West. The editors showed their right-wing opinions by publishing an article in praise of the British Fascisti Party. It argued that its "primary intention is to counteract the present and every-growning trend towards revolution... it is of the utmost importance that centres should be started in the universities and in our public schools".

His mother decided he was unlikely to follow his brother, Peter Fleming to Oxford University, and arranged for him to attend the Sandhurst Royal Military College. However, he was not suited to military discipline and left without a commission in 1927, following an incident with a woman in which, to his mother's horror, he managed to contract a venereal disease.

His mother, Eve Fleming inherited her husband's large estate in trust, making her very wealthy. This did come with conditions that stated she would lose this money if she remarried. She became the mistress of painter Augustus John with whom she had a daughter, the cellist Amaryllis Fleming.

Fleming was sent to study in Kitzbühel, Austria, where he met Ernan Forbes Dennis, a former British spy turned educationist, and his wife, Phyllis Bottome, an established novelist. It was while staying with the couple that he first considered a career as a writer. Fleming later wrote to Phyllis: "My life with you both is one of my most cherished memories, and heaven knows where I should be today without Ernan."

After studying briefly at the universities in Munich and Geneva, Fleming considered becoming a diplomat but he failed the competitive examination for the Foreign Office. His mother used her contacts to get him work as a journalist. This included reporting on the trial of six engineers working for a British company, Metropolitan-Vickers, who had been accused of spying in the Soviet Union. While in Moscow he attempted to get an interview with Joseph Stalin. After this rejection he returned to London.

In August 1935 Fleming met Muriel Wright while on holiday at Kitzbühel. Over the next four years they spent a great deal of time together. Fleming was dazzled by her looks but did not find her very stimulating company and continued to have relationships with other women, this included Mary Pakenham and Ann O'Neill, the wife of Shane Edward Robert O'Neill. Pakenham later recalled that he had two main topics of conversation - himself and sex: "He was always trying to show me obscene pictures of one sort or another. No one I have known has had sex so much on the brain as Ian in those days." Muriel's brother, Fitzherbert Wright, heard about the way Fleming was treating his sister and arrived at Ian's flat with a horsewhip. He was not there as he had taken Muriel to Brighton for the weekend.

Eve Fleming insisted her son sought a career in the family business of banking. He worked briefly for a small bank before joined Rowe and Pitman, a leading firm of stockbrokers. He hated the work and on the outbreak of the Second World War a family friend, the Governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman, arranged for Fleming to join the naval intelligence division as personal assistant to Admiral John Godfrey, the director of naval intelligence.

According to the author of Ian Fleming (1996): "With his charm, social contacts, and gift for languages, Fleming proved an excellent appointment. Working from the Admiralty's Room 39, he showed a hitherto unacknowledged talent for administration, and was quickly promoted from lieutenant to commander. He liaised on behalf of the director of naval intelligence with the other secret services. One of few people given access to Ultra intelligence, he was responsible for the navy's input into anti-German black propaganda."

It has been claimed that Fleming was involved in the plot to lure Rudolf Hess to Britain. Richard Deacon, the author of Spyclopaedia: The Comprehensive Handbook of Espionage (1987), has argued: "The truth is that a number of wartime intelligence coups credited to other people were really manipulated by Fleming. It was he who originated the scheme for using astrologers to lure Rudolf Hess to Britain. Fleming's contract in Switzerland succeeded in planting on Hess an astrologer who was also a British agent. To ensure that the theme of the plot was worked into a conventional horoscope the Swiss contract arranged for two horoscopes of Hess to be obtained from astrologers known to Hess personally so that the faked horoscope would not be suspiciously different from those of the others."

Fleming worked with Colonel Bill Donovan, the special representative of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on intelligence co-operation between London and Washington before Pearl Harbor. Fleming met William Stephenson and Ernest Cuneo in New York City in the summer of 1940. Fleming criticised Admiral Ernest King, Chief of US naval operations for not supporting the Russian convoys forcefully enough. Cuneo responded by claiming that Fleming was only a junior officer who was unlikely to know enough about the subject. Fleming commented: "Do you question my bona fides?" Fleming asked angrily. "No, only your patently limited judgement." Despite this exchange the two men soon became close friends.

Cuneo described Fleming as having the appearance of a lightweight boxer. It was not only his broken nose but the way he carried himself: "He did not rest his weight on his left leg; he distributed it, his left foot and his shoulders slightly forward." Cuneo liked Fleming's "steely patriotism" and told General William Donovan that he was a typical English agent: "England was not a country but a religion, and that where England was concerned, every Englishman was a Jesuit who believed the end justified the means." In May 1941 Fleming accompanied Admiral John Godfrey to America, staying to help write a blueprint for the Office of Co-ordinator of Information (the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency).

During the Second World War Fleming's great friend, Ivar Bryce worked as an SIS agent attached to William Stephenson in New York City. It is claimed that based in Jamaica (his wife Sheila, owned Bellevue, one of the most important houses on the island), Bryce ran dangerous missions into Latin America. Fleming visited Bryce in 1941 and told him that: "When we have won this blasted war, I am going to live in Jamaica. Just live in Jamaica and lap it up, and swim in the sea and write books."

In 1942 Fleming was instrumental in forming a unit of commandos, known as 30 Commando Assault Unit (30AU), a group of specialist intelligence troops, trained by the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The unit was based on a German group headed by Otto Skorzeny, who had undertaken similar activities for Nazi Germany. The unit was initially deployed for the first time during the Dieppe Raid in August 1942, and then took part in the Operation Torch landings in November 1942. The unit went on to serve in Norway, Sicily, Italy, and Corsica between 1942–1943. In June 1944 they took part in the D-Day landings, with the objective of capturing a German radar station at Douvres-la-Delivrande.

During the war, Fleming's girlfriend, Muriel Wright became an air raid warden in Belgravia. However, according to a friend she found the uniform unflattering. She now became a small team of despatch riders at the Admiralty who roared around London on BSA motorcycles. Muriel was killed during an air raid in March 1944. Andrew Lycett, the author of Ian Fleming (1996) has pointed out: "All such casualties are, by definition, unlucky, but she was particularly so, because the structure of her new flat at 9 Eaton Terrace Mews was left intact. She died instantly when a piece of masonry flew in through a window and struck her full on the head. Because there was no obvious damage, no one thought to look for the injured or dead; it was only after her chow, Pushkin, was seen whimpering outside that a search was made. As her only known contact, Ian was called to identify her body, still in a nightdress. Afterwards he walked round to the Dorchester and made his way to Esmond and Ann's room. Without saying a word he poured himself a large glass of whisky, and remained silent. He was immediately consumed with grief and guilt at the cavalier way he had treated her." His friend, Dunstan Curtis, commented: "The trouble with Ian is that you have to get yourself killed before he feels anything."

Ian Fleming was also having an affair with Ann O'Neill, the wife of Lieutenant Colonel Shane Edward Robert O'Neill. He was killed in Italy in October 1944. Although she then went on to marry Esmond Cecil Harmsworth, heir to Lord Rothermere, the owner of The Daily Mail, Fleming continued to see Ann on a regular basis.

After the war Fleming joined the Kemsley Newspaper Group as foreign manager. His friend, Ivar Bryce, helped Fleming find a holiday home and twelve acres of land just outside of Oracabessa. It included a strip of white sand on a lovely part of the coast. Fleming decided to call the house, Goldeneye, after his wartime project in Spain, Operation Goldeneye. Their former boss, William Stephenson, also had a house on the island overlooking Montego Bay. Stephenson had set up the British-American-Canadian-Corporation (later called the World Commerce Corporation), a secret service front company which specialized in trading goods with developing countries. William Torbitt has claimed that it was "originally designed to fill the void left by the break-up of the big German cartels which Stephenson himself had done much to destroy."

Fleming continued her affair with Ann Harmsworth. She told her husband she was staying with Fleming's neighbour, Noël Coward. Ann wrote to Fleming in 1947 after one of her visits: "It was so short and so full of happiness, and I am afraid I loved cooking for you and sleeping beside you and being whipped by you... I don't think I have ever loved like this before." Fleming replied: "All the love I have for you has grown out of me because you made it grow. Without you I would still be hard and dead and cold and quite unable to write this childish letter, full of love and jealousies and adolescence." In 1948 Ann gave birth to his daughter, Mary, who lived only a few hours.

Fleming negotiated a favourable contract with Kemsley Newspaper Group that allowed him to take three months' holiday every winter in Jamaica. Fleming loved the time he spent at Goldeneye: "Every exploration and every dive results in some fresh incident worth the telling: and even when you don't come back with any booty for the kitchen, you have a fascinating story to recount. There are as many stories of the reef as there are fish in the sea."

After the war Ernest Cuneo joined with Ivar Bryce and a group of investors, including Fleming, to gain control of the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA). Andrew Lycett has pointed out: "With the arrival of television, its star had begun to wane. Advised by Ernie Cuneo, who told him it was a sure way to meet anyone he wanted, Ivar stepped in and bought control. He appointed the shrewd Cuneo to oversee the American end of things... and Fleming was brought on board to offer a professional newspaperman's advice." Fleming was appointed European vice-president, with a salary of £1,500 a year. He persuaded James Gomer Berry, 1st Viscount Kemsley, that The Sunday Times should work closely with NANA. He also organized a deal with The Daily Express, owned by Lord Beaverbrook.

Fleming considered the possibility of writing detective fiction. In December 1950 he travelled to New York City to meet with Ernest Cuneo and William Stephenson. Fleming's biographer points out: "With William Stephenson's and Ernie Cuneo's help - Ian spent a night out on the Upper West Side with a couple of detectives from the local precinct. On previous trips he had enjoyed visiting Harlem dance clubs, where he delighted in their energy as much as their music. Now his eyes had been opened to a seedier reality. He met a local crime boss and witnessed with alarm the hold that drug traffickers were gaining in the neighbourhood." Cuneo took the opportunity to tell Fleming that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was a communist front.

Fleming often visited the United States to be with Cuneo. This included doing research in Las Vegas for a novel he was planning. Cuneo argued that Fleming was "a knight errant searching for the lost Round Table and possibly the Holy Grail, and unable to reconcile himself that Camelot was gone and still less that it had probably never existed."

In 1951 Esmond Cecil Harmsworth, who discovered her relationship with Fleming, divorced Ann. Her £100,000 divorce settlement enabled her to live in luxury with the unemployed Fleming. On 24th March 1952 she married Fleming. The very next day, he sat down and began writing Casino Royale. Ann wrote in her diary: "This morning Ian started to type a book. Very good thing." Every morning after a swim he breakfasted with Ann in the garden. After he finished his scrambled eggs, he settled in the main living-room and for the next three hours he "pounded the keys" of his twenty-year-old portable typewriter. He took lunch at noon and afterwards slept for an hour or so. He then returned to his desk and corrected what he had written in the morning.

John Pearson, the author of The Life of Ian Fleming (1966) claims that Fleming wrote a 62,000 word manuscript in eight weeks. He later claimed that he wrote Casino Royale in order to take his mind of being married. Andrew Lycett has argued that in reality, there were other reasons for this burst in creativity: "It was not so much his marriage that spurred Ian as the fait accompli of Ann's pregnancy, which created a new set of circumstances, partly physical - with her need to take her pregnancy carefully, she was hors de combat sexually, so Ian had time and energy on his hands - and partly psychological - Ian realized that, at the age of forty-three, the imminent arrival of his first-born child would change his life more radically than anything he had done before. With no great financial resources behind him, he needed to provide for his off-spring, whatever sex it turned out to be. Casino Royale was to be his child's birthright."

Fleming's novel, Casino Royale, featuring the secret agent James Bond, was published to critical acclaim in April 1953. Fleming later admitted that Bond was based on his wartime colleague, William Stephenson: "James Bond is a highly romanticized version of a true spy. The real thing is... William Stephenson." The 'M' character was inspired by Maxwell Knight, the head of B5b, a unit that conducted the monitoring of political subversion. The Flemings bought a Regency house in Victoria Square, London, and Ann Fleming gained a reputation for giving lunch and dinner parties attended by new literary friends, including Cyril Connolly and Evelyn Waugh.

Barbara Skelton, the wife of George Weidenfeld, and a published novelist, was one of the many visitors to Goldeneye. Unlike most women she did not find Ian attractive: "His eyes were too close together and I don't fancy his raw beef complexion." She accepted that Ann was attractive and "well-bred" but added, "why does she always rouge her cheeks like a painted doll?"

Fleming gave an insight into the writing process when he gave Ivar Bryce advice on writing his memoirs: "You will be constantly depressed by the progress of the opus and feel it is all nonsense and that nobody will be interested. Those are the moments when you must all the more obstinately stick to your schedule and do your daily stint... Never mind about the brilliant phrase or the golden word, once the typescript is there you can fiddle, correct and embellish as much as you please. So don't be depressed if the first draft seems a bit raw, all first drafts do. Try and remember the weather and smells and sensations and pile in every kind of contemporary detail. Don't let anyone see the manuscript until you are very well on with it and above all don't allow anything to interfere with your routine. Don't worry about what you put in, it can always be cut out on re-reading; it's the total recall that matters."

The journalist, Christopher Hudson, has claimed the Flemings were practitioners of sadomasochism: "Those who were lucky enough to visit Goldeneye, Ian Fleming's Jamaican retreat, could never understand how the Flemings went through so many wet towels. But those sodden towels were needed, literally, to cool their fiery partnership, used to relieve the stinging of the whips, slippers and hairbrushes the pair beat each other with - Ian inflicting pain more often than Ann - as well as to cover up the weals Ian made on Ann's skin during their fiery bouts of love-making." She wrote to Fleming: "I long for you to whip me because I love being hurt by you and kissed afterwards. It's very lonely not to be beaten and shouted at every five minutes." Hudson goes on to argue: "The pregnancy which led to their marriage resulted in Caspar, their first and only child. The birth, Ann's second Caesarian, left wide scars on her stomach, to the disgust of Fleming who had a horror of physical abnormality. Ann said it marked the end of their love-making."

Fleming followed Casino Royale with Diamonds Are Forever (1956). It received mixed reviews. Anthony Boucher wrote in the New York Times that Fleming "writes excellently about gambling, contrives picturesque incidents but the narrative is loose-joined and weekly resolved". Fleming defended himself by claiming that he was writing "fairy tales for grown-ups."

From Russia With Love appeared in 1957 and Dr No in 1958. Ann Fleming spent her time painting while Fleming wrote his books. She told Evelyn Waugh, "I love scratching away with my paintbrush while Ian hammers out pornography next door.

Fleming's biographer, Andrew Lycett, has argued: "Bond reflected much of Fleming: his secret intelligence background, his experience of good living, his casual attitude to sex. He differed in one essential - Bond was a man of action, while Fleming had mostly sat behind a desk. Fleming's news training was evident in his lean, energetic writing (with its dramatic set-piece essays on subjects that interested him, such as cards or diamonds) and in his desire to reflect contemporary realities, not only politically but sociologically. He was aware of Bond's position as a hard, often lonely professional, bringing glamour to the grim post-war 1950s. Fleming broke new ground in giving Bond an aspirational lifestyle and larding it with brand names."

Fleming spent a lot of time in Jamaica where he had an affair with Millicent Rogers, the granddaughter of Standard Oil tycoon Henry Huttleston Rogers, and an heiress to his wealth. He also had relationships with Jeanne Campbell and the novelist, Rosamond Lehmann. However, his most important relationship was with Blanche Blackwell who he met in 1956. Blanche described him as a fine physical specimen, "six foot two inches tall, with blue eyes and coal black hair, and so rugged and full of vitality." Blanche told Jane Clinton: “Don’t forget I met him when he was 48. In his early life I believe he did not behave terribly well. I knew an Ian Fleming that I don’t think a lot of people had the good fortune to know. I didn’t fawn over him and I think he liked that.... She (Ann Fleming) disliked me but I can’t blame her. When I got to know Ian better I found a man in serious depression. I was able to give him a certain amount of happiness. I felt terribly sorry for him.”

Sebastian Doggart has claimed that Blackwell was "the inspiration for Dr. No's Honeychile Ryder, whom Bond first sees emerging from the waves – naked in the book, bikini-clad in the movie." As well as Honeychile Ryder it has been argued that Fleming based the character of Pussy Galore , who appeared in Goldfinger on Blackwell.

Ann Fleming developed an interest in politics through her friend Clarissa Churchill, who had married Sir Anthony Eden, the leader of the Conservative Party. However during this period she began an affair with Hugh Gaitskell, the leader of the Labour Party. Brian Brivati, the author of Hugh Gaitskell (1996) has pointed out: "Friends and close colleagues worried both that the liaison would damage Gaitskell politically and that the kind of society life that Fleming lived was far removed from the world of Labour politics. Widely known in journalistic circles, though never reported, his attachment did not outwardly affect his marriage, but it did show the streak of recklessness and the overpowering emotionalism in his character that so diverged from his public image."

In March 1960, Henry Brandon contacted Marion Leiter who arranged for Fleming to have dinner with John F. Kennedy. The author of The Life of Ian Fleming (1966), John Pearson, has pointed out: "During the dinner the talk largely concerned itself with the more arcane aspects of American politics and Fleming was attentive but subdued. But with coffee and the entrance of Castro into the conversation he intervened in his most engaging style. Cuba was already high on the headache list of Washington politicians, and another of those what’s to-be-done conversations got underway. Fleming laughed ironically and began to develop the theme that the United States was making altogether too much fuss about Castro – they were building him into a world figure, inflating him instead of deflating him. It would be perfectly simple to apply one or two ideas which would take all the steam out of the Cuban." Kennedy asked him what would James Bond do about Fidel Castro. Fleming replied, “Ridicule, chiefly.” Kennedy must have passed the message to the CIA for on as the following day Brandon received a phone-call from Allen Dulles, asking for a meeting with Fleming.

Fleming published a collection of short stories, For Your Eyes Only in 1960. Maurice Richardson, writing in Queen Magazine, argued that Fleming's short stories "give you the feeling that Bond's author may be approaching one of those sign-posts in his career and thinking about taking a straighter path."

Ivar Bryce became a film producer and helped to finance The Boy and the Bridge (1959). The film lost money but Bryce decided he wanted to work with its director, Kevin McClory, again and it was suggested that they created a company, Xanadu Films. Fleming, Josephine Hartford and Ernest Cuneo became involved in the project. It was agreed that they would make a movie featuring Fleming's character, James Bond.

The first draft of the script was written by Cuneo. It was called Thunderball and it was sent to Fleming on 28th May. Fleming described it as "first class" with "just the right degree of fantasy". However, he suggested that it was unwise to target the Russians as villains because he thought it possible that the Cold War could be finished by the time the film had been completed. He suggested that Bond should confront SPECTRE, an acronym for the Special Executive for Counterintelligence, Revolution and Espionage. Fleming eventually expanded his observations into a 67-page film treatment. Kevin McClory now employed Jack Whittingham to write a script based on Fleming's ideas.

The Boy and the Bridge was a flop at the box-office and Bryce, on the recommendation of Ernest Cuneo, decided to pull-out of the James Bond film project. McClory refused to accept this decision and on 15th February, 1960, he submitted another version of the Thunderball script by Whittingham. Fleming read the script and incorporated some of the Whittingham's ideas, for example, the airborne hijack of the bomb, into the latest Bond book he was writing. When it was published in 1961, McClory claimed that he discovered eighteen instances where Fleming had drawn on the script to "build up the plot".

Fleming continued to live with Ann Fleming. He wrote to her: "The point lies only in one area. Do we want to go on living together or do we not? In the present twilight we are hurting each other to an extent that makes life hardly bearable." He recorded in his diary: "One of the great sadnesses is the failure to make someone happy." Ann told Cyril Connolly, that Fleming had constantly moaned: "How can I make you happy, when I am so miserable myself?"

In an attempt to make the relationship work they purchased a house in Sevenhampton. His mistress, Blanche Blackwell, moved to England to continue the relationship. Every Thursday morning Blanche would drive him down to Henley where they would have lunch at the Angel Hotel.

President John F. Kennedy was a fan of Fleming's books. In March 1961, Hugh Sidey, published an article in Life Magazine, on President Kennedy's top ten favourite books. It was a list designed to show that Kennedy was both well-read and in tune with popular taste. It included Fleming's From Russia With Love. Up until this time, Fleming's books had not sold well in the United States, but with Kennedy's endorsement, his publishers decided to mount a major advertising campaign to promote his books. By the end of the year Fleming had become the largest-selling thriller writer in the United States.

This publicity resulted in Fleming signed a film deal with the producers, Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, in June 1961. Dr No, starring Sean Connery, opened in the autumn of 1962 and was an immediate box-office success. As soon as it was released Kennedy demanded a showing in his private cinema in the White House. Encouraged by this new interest in his work, Fleming produced another James Bond book, On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963).

Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham became angry at the success of the James Bond film and believed that Fleming, Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo had cheated them out of making a profit out of their proposed Thunderball film. The case appeared before the High Court on 20th November 1963. Three days into the case, when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. McClory's solicitor, Peter Carter-Ruck, later recalled: "The hearing was unexpectedly and somewhat dramatically adjourned after leading counsel on both sides had seen the judge in his private rooms." Bryce agreed to pay the costs, and undisclosed damages. McClory was awarded all literary and film rights in the screenplay and Fleming was forced to acknowledge that his novel was "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the author."

Ian Fleming, who was a heavy drinker and smoker, died from a heart-attack, on 12th August 1964. According to Christopher Hudson: "Ann never recovered from grief that she had not made Fleming happy... took to the bottle".

At the time of his death Fleming had sold 30 million books. In 1965 over 27 million copies of Fleming's novels were sold in eighteen different languages, producing an income of £350,699. In less than two years, his sales more than doubled those he had achieved in his lifetime. People continued to watch Dr No and it went on to gross $16 million around the world.

The popularity of Fleming's work resulted in heavy criticism. Malcolm Muggeridge, described him as an "Etonian Micky Spillane" who was "utterly despicable; obsequious to his superiors, pretentious in his tastes, callous and brutal in his ways, with strong undertones of sadism, and an unspeakable cad in his relations with women, towards whom sexual appetite represents the only approach."

Newspapers from behind the Iron Curtain were especially critical of Fleming's work. Pravda attacked him for creating "a world where the laws are written from a pistol barrel, and rape and outrages on female are considered gallantry". In April 1965 Neues Deutschland reported: "There is something of Bond in the snipers of the streets of Selma, Alabama. He is flying with the napalm bombers over Vietnam... The Bond films and books contain all the obvious and ridiculous rubbish of reactionary doctrine. Socialism is synonymous with crime. Unions are fifth columns of the Soviet Union. Slavs are killers and sneaks. Scientists are amoral eggheads. Negroes are superstitious, murderous lackeys. Persons of mixed race are trash."

John le Carre, was another who criticised the work of Ian Fleming. He has described Fleming's novels as "cultural pornography". He has stated that what he disliked most was "the Superman figure who is ennobled by some sort of misty, patriotic ideas and who can commit any crime and break any law in the name of his own society. He's a sort of licensed criminal who, in the name of false patriotism, approves of nasty crimes."

On this day in 1937 Alfred Adler collapsed on a street in Aberdeen with a fatal heart attack on 28th May, 1937. Sigmund Freud wrote to Arnold Zweig that he had hated Adler for over 25-years. Freud had written in Civilization and Its Discontents (1929) that he could not understand the Christian injunction to universal love as many people were hateful. According to Freud, the most hateful were those like Adler who he thought had let him down.

Adler, the second of seven children, was born in Rudolfsheim, a village near Vienna on 7th February, 1870. Adler's father was a Hungarian-born, sharp-witted, Jewish grain merchant. He developed rickets and did not walk until he was four years old. As a child he also suffered from pneumonia and he heard a doctor say to his father, "Your boy is lost".

Franz Alexander has argued: "While still uncertain on his feet, he was involved in a series of street accidents. Nevertheless, he did not resign himself to a life of infirmity. After frequent contacts with physicians, Adler resolved to become a doctor. While longing for the days when he could join the other boys in athletics, he spent his time reading works of the great classical writers."

Alfred Adler later recalled that "my eldest brother was the only one with whom I did not get along well". He felt his mother showed her preference for this elder son. Adler got on much better with his father who praised him for his intellectual abilities and his relationship with his two younger sisters and his two younger brothers were also harmonious.

While studying at the University of Vienna he met Raissa Epstein. Born in Moscow she had been involved in left-wing politics in Russia and was a friend of leading Bolsheviks such as Leon Trotsky and Adolph Joffe. Raissa had left her home country because women were not allowed to study at the Russian universities. He received his medical degree in 1895 and two years later he married Raissa and over the next few years gave birth to four children. According to Hendrika Vande Kemp: "Raissa Epstein Adler, a radical socialist, influenced her husband’s views on women and served as a feminist model for her daughters and son."

Adler began his medical career as an ophthalmologists, later switching to general practice. Despite his busy practice he continued to study philosophy and sociology. He also read the early work of the early psychologist, Richard von Krafft-Ebing. It was during this period he rejected Judaism because it was a religion for only one ethnic group and he wanted to "share a common deity with the universal faith of man". However, in reality, all the children were brought up as atheists.

Adler became a psychologist but later recalled that when he was a young man he was "discontented with the state of psychiatry". At this time he became aware of the work of Sigmund Freud who had published several important books such as Studies on Hysteria (1895), The Interpretation of Dreams (1899) and Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905). "He (Freud) was courageous enough to go another way, and to find the importance psychic reasons for bodily disturbances and for the neuroses."

After reading a hostile review of one of Freud's books in the Neue Freie Presse, wrote a letter of protest to the newspaper. According to Adler's biographer, Phyllis Bottome, "Freud was much touched by it and sent Adler the famous postcard thanking him for his defence and asking him to join the discussion circle of psychoanalysis." Freud small group of his followers who met every Wednesday evening and became known as the "Wednesday Psychological Society".

Each week someone would present a paper and, after a short break for black coffee and cakes, a discussion would be held. The main members of the group included Otto Rank, Max Eitingon, Wilhelm Stekel, Karl Abraham, Hanns Sachs, Fritz Wittels and Sandor Ferenczi. Stekel claimed that it was his idea to form this group: "Gradually I became known as a collaborator of Freud. I gave him the suggestion of founding a little discussion group; he accepted the idea, and every Wednesday evening after supper we met in Freud's home... These first evenings were inspiring."

It was clear that Freud was the dominant character in the group that were mostly Jews. Hanns Sachs said he was "the apostle of Freud who was my Christ". Another member said "there was an atmosphere of the foundation of a religion in that room. Freud himself was its new prophet... Freud's pupils - all inspired and convinced - were his apostles." Another member remarked that the original group was "a small and daring group, persecuted now but bound to conquer the world".

Fritz Wittels argued that Freud did not like members of his group to be too intelligent: "It did not matter if the intelligences were mediocre. Indeed, he had little desire that these associates should be persons of strong individuality, that they should be critical and ambitious collaborators. The realm of psychoanalysis was his idea and his will, and he welcomed anyone who accepted his views. What he wanted was to look into a kaleidoscope lined with mirrors that would multiply the images he introduced into it."

The Wednesday meetings sometimes ended in conflict. However, Freud was very good at controlling the situation: "His diplomatic skill in modifying both his own demands and those of rivals was married to a determined effort to remain scientifically detached. Time and again his cool voice and calming influence broke into heated discussions and a volcanic situation was checked before it erupted. Considerable wisdom and tolerance marked many of his utterances and occasionally there was a tremendous sense of a figure, Olympian beside the pigmies around him, who quietened the waters with the wand of reason. Unfortunately, this side of Freud's character was heavily qualified by another. When someone put forward a proposition which seriously disturbed his own views, he first found it hard to accept and then became uneasy at this threat to the scientific temple he had so painfully built with his own hands."

Unlike other members of the group, Alfred Adler openly questioned Freud's fundamental thesis that early sexual development is decisive for the making of character. Adler forcefully evolved a distinctive family of ideas. According to Peter Gay, the author of Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989), "Adler... secured an ascendancy among his colleagues second only to Freud." However, Freud disliked his socialist approach to the subject, "as a Socialist and social activist interested in the amelioration of humanity's lot through education and social work." Freud once told Karl Abraham that "politics spoils the character".

As early as 1904, Adler told Freud in writing that he did not intend to participate any longer in the Wednesday discussions. Freud then wrote a long letter to Adler, in which he asked him to change his mind and also flattered him by saying that he considered him the "sharpest head" in the entire circle. "In a conversation that then materialized from his suggestion, Freud was able to sway Adler to revoke his decision."

Alfred Adler developed a new theory in 1906 based on his work as a general practitioner near Vienna's famous amusement park. According to Carl Furtmüller: "Artists and acrobats of the shows. All of these people, who owned their living by exhibiting their extraordinary bodily strength and skills, showed to Adler their physical weaknesses and ailments. It was partly the observation of such patients as these that led to his conception of over-compensation."

Adler gives the example of Demosthenes who in boyhood had a speech defect: "The stammering boy Demosthenes became Greece's greatest orator." Peter Hofstätter disagreed with this example: "Demosthenes, who once stammered, is the classic paradigm of overcompensation. But the facts in this case, too, are not so easily determined, because first of all, stammering is not dependent on an inferior organ, but is really already itself a failed overcompensation - the act of speaking becomes problematic by the excess of attention directed to it."

Adler believed the effort of compensation always conditioned an increase in brain capacity: "Organ inferiority is counterbalanced by a higher achievement of the brain." A sense of inferiority is the bases of neuroses and psychoses. Adler wrote: "From the attempt to compensate, or to overcome a physical defect or lack - that is, an organ inferiority - functional supervalence, even genius, can follow; but a mental illness, namely neurosis, is just as likely."

During the first presentation of his idea, Adler used the example of the deafness of Ludwig van Beethoven of how a person can turn a defect into greatness. At first Freud agreed with Adler's theory as it could be linked to the sexual instinct that he believed was so dominant. During the meeting he suggested that the individual's egotism or excessive ambition might be connected to a sense of inferiority.

Carl Jung was present at a meeting of the Wednesday Psychological Society where Adler came under attack for his "inferiority complex" theory: "The criticism directed at the doctrine of organ inferiority seemed too harsh to him (Jung). In his opinion, it was a brilliant idea, which we (the participants) are not justified in criticizing because we lack sufficient experience."

In 1908 Adler presented the paper, The Aggressive Instinct in Life and in Neurosis, where he took a look at the concepts of sadism and masochism. "Until now, every examination of sadism and masochism has taken as its starting point those sexual manifestations in which traits of cruelty are added. The driving force, however, apparently derives in healthy people... apparently from two originally separate instincts which merge later on. From this it follows that a resulting sadomasochism corresponds to simultaneous instincts: the sexual instinct and the aggressive instinct."

Adler began to argue that the "aggressive instinct" flowed into other areas such as the "striving for power" or "striving for superiority". Freud rejected this idea: "I cannot bring myself to assume the existence of a special aggressive drive alongside of the familiar instincts of self-preservation and of sex, and on an equal footing with them. It appears to me that Adler has mistakenly promoted into a special and self-subsisting instinct what is in reality a universal and indispensable attribute of all instincts what is in reality a universal and indispensable attribute of all instincts."

On 11th March, 1908, Fritz Wittels gave a presentation on "The Natural Position of Women". In the paper Wittels attempted to define the "natural" position of women. He condemned "our accursed present-day culture in which women bemoan the fact that they did not come into the world as men; they try however to become men. People do not appreciate the perversity and senselessness of these strivings; nor do the women themselves."

Sigmund Freud gave his support to Wittels but Adler dismissed his views as reactionary: "Whereas it is generally assumed that the framework of present relationships between men and women is constant, Socialists assume that the framework of the family is already shaky today and will increasingly become so in the future. Women will not allow motherhood to prevent her from taking up a profession... Under the sway of private ownership, everything becomes private property, so does woman. First she is the father's possession, then the husband's. That determines her fate. Therefore, first of all, the idea of owning a woman must be abandoned."

The following year Adler gave a lecture "On the Psychology of Marxism". He looked at the ideas of Karl Marx and claimed "that his exposition has demonstrated that the theory of the class struggle is clearly in harmony with the results of our teachings of instincts". He also suggested that Marx and Freud agreed on the subject of religion: "Marx was the first to offer the suppressed classes the chance to free themselves of Christianity - by the new outlook that he gave them."

Some members of the group were hostile to these ideas and Maximilian Steiner suggested that socialism was a form of neurosis. Adler replied: "It is not a matter of neurosis: in the neurotic, we see the instinct of aggression inhibited, while class consciousness liberates it; Marx shows how it can be gratified in keeping with the meaning of civilization: by grasping the true causes of oppression and exploitation, and by suitable organization."

In 1908 the Wednesday Psychological Society was disbanded and reconstructed as the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. Adler still remained a member but from Freud's point of view, he was moving steadily away from the central tenet of psychoanalytic theory - the unconscious repression of libido as a cause for neurosis. Adler argued that sometimes the sexual and aggressive drive occur together. Adler took the view that "the aggressive drive was really a mode of striving by which one adapts to arduous life tasks."

In 1910 Adler published The Psychological Hermaphroditism in Life and in the Neurosis where he explained the inferiority complex in great detail. "The feeling of inferiority whips up... the instinctual life, excessively intensifies wishes, gives rise to over sensitivity, and produces a craving for satisfaction that will not tolerate compromise... In this hypertrophied craving, in this addiction to success, in this wildly behaving masculine protest lie the seeds of failure - though also the predestination for genial and artistic achievements."

Alfred Adler wrote to Carl Jung about how he was worried about the development of Adler's theories. "It is getting really bad with Adler. You see a resemblance to Bleuler; in me he awakens the memory of Fliess; but an octave lower... The crux of the matter - and that is what really alarms me - is that he minimizes the sexual drive and our opponents will soon be able to speak of an experienced psychoanalyst whose conclusions are radically different from ours. Naturally in my attitude toward him I am torn between my conviction that all this is lopsided and harmful and my fear of being regarded as an intolerant old man who holds the young men down, and this makes me feel most uncomfortable."

Adler argued that the child feels weak and insignificant in his relationship to adults. He disagreed with Freud's view on the pre-eminence of the sex instinct. Adler believed that it was more important to consider how the individual reacted to feelings of inferiority. Freud found the idea interesting but believed that his theory was a "fact" whereas Adler's theory was "uncorroborated speculation". Freud continued to work with Adler who he thought was "a decent fellow" who was suffering from "paranoid delusions of persecution". He told Ludwig Binswanger that: "It is necessary to be wary of Adler's writings. The danger with him is all the greater considering how intelligent he is."

In an attempt to keep Alfred Adler within the group, Freud arranged for him to replace him as President of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society. Another rebellious member of the group, Wilhelm Stekel, was appointed as Vice-President. Freud also established a new monthly periodical, Central Journal for Psychoanalysis, that was jointly edited by Adler and Stekel. This move did not work and after another dispute in February 1911, both Adler and Stekel resigned their posts.

Adler complained that he had been treated unfairly as "the best heads and the people of honest independence" were on his side. In August 1911, Freud told one of his followers that Adler's behaviour was the "revolt of an abnormal individual driven mad by ambition, his influence upon others depending on his strong terrorism and sadism". (33) As Peter Gay has pointed out that this was "denunciation as diagnosis" and that Freud was "using psychological diagnosis as a form of aggression."

Ernest Jones was a loyal follower of Freud and he had some hostile things to say about Adler: "He (Adler) was evidently very ambitious and constantly quarrelling with the others over points of priority in his ideas... Adler's view of the neuroses was seen from the side of the ego only and could be described as essentially a misinterpreted picture of the secondary defences against the repressed and unconscious impulses... His whole theory had a very narrow and one-sided basis, the aggression arising from 'masculine protest'. Sexual factors, particularly those of childhood, were reduced to a minimum... Adler insisted that the Oedipus complex was a fabrication... The concepts of repression, infantile sexuality, and even that of the unconscious itself were discarded, so that little was left of psycho-analysis."

Bernhard Handlbauer, the author of The Freud-Adler Controversy (1998) has argued that Freud's attitudes reflected his more conservative upbringing: "Fourteen years older than Adler, he was much more strongly shaped by the bygone nineteenth century, in which aggressive revolts against authority were brutally punished. The solid middle-class life he led was based, in fact, on inhibiting - and tabooing - aggressive behaviour. Adler, on the other hand, had married a politically radical and personally emancipated woman."

Nineteen years later Adler explained his dispute with Freud. "In my striving to find a better way (of understanding) I was often in dispute with Freud and his collaborators... As I discovered, every part agrees with all other parts. I saw the marvellous harmony of the style of life. Yet, Freud was pointing out strongly the science of sexual psychology and the sexual libido. This was at a time when he was only interested in the notion that every movement, every expression, and symptom had a sexual factor. Freud insisted culture resulted from the suppression of the sexual libido."

Alfred Adler wrote to Lou Andreas-Salomé explaining his position: "My position toward the Freudian school has has unfortunately never had to take into account its scientific arguments... How could it be that this school tried to treat our ideas as a common good while we always stressed only the falseness of its views? For me, such things are just proof that the Freudian school does not believe at all in its own theses, but rather only intends to save its investments."

Carl Furtmüller has argued that the conflict was partly due to their different personalities. "Freud was the man of the world, careful of his appearance; unsatisfactory though his university career was, knowing how to use the prestige of title and the dignity of a professor... Adler was always the common man, nearly sloppy in his appearance, careless of cigarette ashes dropping on his sleeve or waistcoat, oblivious of outer prestige of all kinds, artless in his way of speaking although knowing very well how to drive his points home."

Adler founded the Society for Individual Psychology in 1912 after his break from the psychoanalytic movement. He had several followers who became known as Adlerians. They believed that "there is one basic dynamic force behind all human activity, a striving from a felt minus situation towards a plus situation, from a feeling of inferiority towards superiority, perfection, totality." The striving receives its specific direction from an "individually unique goal or self-ideal, which though influenced by biological and environmental factors is ultimately the creation of the individual." Although the goal is created by the individual it "is largely unknown to him and not understood by him". This is Adler's definition of the unconscious: "the unknown part of the goal".

Adler's group initially included some supporters of the ideas put forward by Friedrich Nietzsche who argued in books such as Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883), Beyond Good and Evil (1886), Twilight of the Idols (1888) and Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is (1888) that the "will to power" is the main driving force in humans - achievement, ambition, and the striving to reach the highest possible position in life.

Wilhelm Stekel commented that Adler was a "fanatical socialist". Ernest Jones claimed that most of Adler's supporters were socialists: "It is not irrelevant to recall that most of Adler's followers were, like himself, ardent Socialists. Adler's wife, a Russian, was an intimate friend of the leading Russian revolutionaries; Trotsky and Joffe, for instance, constantly frequented her house... This consideration makes it more intelligible that Adler should concentrate on the sociological aspects of consciousness rather than on the repressed unconscious."

In his autobiography, Leon Trotsky admitted that it was Adolph Joffe who introduced him to the ideas of Adler. "Joffe was a man of great intellectual ardour, very genial in all personal relations, and unswervingly loyal to the cause... Joffe suffered from a nervous complaint and was then being psychoanalyzed by the well-known Viennese specialist, Alfred Adler, who began as a pupil of Freud but later opposed his master and founded his own school of individual psychology. Through Joffe I became acquainted with the problems of psychoanalysis, which fascinated me although much in the field is still vague and unstable and opens the way for fanciful and arbitrary ideas."

Alfred Adler was a committed socialist. He argued that all attempts at introducing a more humane system had ended in failure: "All laws of society of the past, the tablets of Moses, the teachings of Christ, always fell into the hands of the powerful who misused the holiest for the purpose of the domination. The most clever falsehoods, the most refined tricks and treachery were called upon to shift the recurrence of the feeling and the creativity of the senses of community toward a striving for power, and thus make it ineffective for the well-being of all. The years of capitalism with their unfettered greed for dominance have aroused rapaciousness in the human soul."

Adler became a supporter of Karl Marx: "Only in socialism did the feeling of community remain as the ultimate goal and end as demanded by unhampered human fellowship. All the inspired socialist utopias who were looking for or discovered social systems, instinctively saw, as did all reformers in history, a mutual interest in the struggle for power. And in the dark machinery of the human soul, Karl Marx discovered the common struggle of the proletariat against class dominance. He encased it forever in the conscience of his supporters and showed a way to a final manifestation of the feeling of the community. The dictatorship of the proletariat was redemption from class confrontation and class striving for power."

Adler believed that the desires for socialism was connected to man's feeling of inferiority: "In every country, socialism is at the point of fruition... It was the proletariat's feeling of inferiority in his struggle for survival that, like a thorn causing irritation, made him search for a new way to overcome the suppressor and to discover a better organization and a better economic system."

On the outbreak of the First World War, some socialists in Germany such as Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Paul Frölich and Paul Frölich, called for people not to serve in the armed forces. However, Liebknecht was the only member of the Reichstag who voted against Germany's participation in the First World War. He argued: "This war, which none of the peoples involved desired, was not started for the benefit of the German or of any other people. It is an Imperialist war, a war for capitalist domination of the world markets and for the political domination of the important countries in the interest of industrial and financial capitalism. Arising out of the armament race, it is a preventative war provoked by the German and Austrian war parties in the obscurity of semi-absolutism and of secret diplomacy."

The leadership of the German Social Democratic Party argued that it was the duty of socialists to join the armed forces. Adler was unwilling to fight but volunteered to serve in the medical corps in the Austrian-Hungarian Army. The war had a great influence on his thinking. "The ideal of peace, Adler thought could be accessible only when man surrenders his self-centered orientation, which seeks to overcome feelings of insignificance. Even during the horrors of war, Adler had seen remarkable examples of man's unselfish duty to his fellow beings. From those days onward, Adler began to emphasize the importance of 'good-will', not with a 'will to power', could man find his full potential."

In 1917 Alfred Adler published Study of Organ Inferiority and its Psychical Compensation. He explained that compensation is a strenuous effort to make up for failure or weakness in one activity through excelling in a either a different or an allied activity. The boy who fails at sport may compensate for the failure by working very hard at his academic studies. Adler also identified "overcompensation" where an individual attempts to deny a weakness by trying to excel where one is weakest.

It has been claimed that illustrations of this are not hard to find. "The power-driven dictators of recent times have been mostly men of short stature, who may have suffered a sense of physical powerlessness for which they over-compensated by a struggle for political might. Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin were short, as was Napoleon before them. Theodore Roosevelt, a frail boy with weak eyes, took up boxing at Harvard and later led the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War. Overcompensation is an energetic and effective (though not necessarily admirable) way of meeting weakness."

In an article, Bolshevism and Psychology (1918), Alfred Adler attempted to apply his psychological theories to the current political situation. Adler welcomed the fall of the German Empire: "The means of power have been torn from us Germans... The victor's laurel that adorns the brow of the strong commander does not lead to anguish in us. We were the infatuated for many years and have now become wiser. Behind the sorrow and the misery of the present our people see the shining glimmer of a new realization. We were never more miserable than in the height of our power! The striving for power is an ill-fated delusion that poisons human fellowship! Whoever seeks fellowship must forsake the striving for power."

Adler went on to argue that defeat of Germany and Austria had created certain advantages: "We are closer to the truth than are the victors. We have behind us the sudden collapse that threatens others... A deep tragedy such as our people experienced must make for vision or else it misses its only sensible purpose. Out of its agonizing experience, the renewed Germany brings us the most deep-seated belief of all civilizations in the final rejection of the striving of people and in the irrevocable raising of the sense of community to be the guiding thought."

However, Adler, like others on the left, had not supported the Russian Revolution. He agreed that the regime of Tsar Nicholas II had been appalling but it had been wrong of the Bolsheviks to overthrow the government. "Under the coercive regime of the Tsars, depravity is inflamed and spreads senseless violence across the land. Whoever, still has any vitality directs his thoughts toward cunning and force in order to overthrow the rule of the tyrant. Driving a resisting multitude of people into an artificial socialist form of government is akin to destroying a costly vase out of impatience."

As a supporter of Karl Marx, Adler believed that the revolution should only take place when it had the support of the majority of the people. He argued that people had to go through an important educational process before socialism could be introduced: "Every form of education must aim for the most favourable conditions for receptiveness... Lasting retention comes about only for what a person has received as a subject and accepted by his own will. The process of Bolshevism shows all the mistakes of a poor, antiquated method. Even if it were to succeed somewhere by subjecting a majority, no one would be happy. Socialism without the appropriate philosophy of life is living like a puppet without a soul, initiative, or talent. If Bolshevism succeeds, it will have compromised and vulgarized socialism."

Influenced by the work of Eduard Bernstein, Adler declared that socialism could best be attained by reformist, parliamentary, evolutionary and educational methods. In 1919 the school system of Vienna sought Adler's advice, and, in 1919, he founded the first child guidance clinic in the city. Adler was an early advocate in psychology for prevention and emphasized the training of parents, teachers, social workers that allow a child to exercise their power through reasoned decision making whilst co-operating with others for the good of society.

Adler took a keen interest in the curriculum and believed that history teaching had prepared young men to fight in nationalist wars: "Daily these people were subjected in their schools to lectures on their obligation to honour the ruling house. All the melodies of their childhood fill their ears with awesome sounds flattering and praising the monarchy. Distorted history boasts of bellicose glory... and seduces the souls of boys to seek mystical bliss in bloodshed and in battles. Incessant eloquent sermons pour from thousands of pulpits preaching the exhilaration of servitude and slavish obedience. Every seat of learning teaches the student the art of subservience."

Adler continued to write about the importance of the feeling of inferiority in motivating individuals. In his article, The Practice and Theory of Individual Psychology (1923) he argued: "The striving for significance, this sense of yearning, always points out to us that all psychological phenomena contain a movement that starts from a feeling of inferiority and reach upward. The theory of Individual Psychology of psychological compensation states that the stronger the feeling of inferiority, the higher the goal for personal power."

In his book, Understanding Human Nature (1927), Adler looked at a variety of different subjects, including birth-order. Adler believed that the firstborn child would be in a favorable position, enjoying the full attention of the new parents until the arrival of a second child. This second child would cause the first born to suffer feelings of dethronement, no longer being the center of attention. Adler insisted that the oldest child would be the most likely to suffer from neuroticism which he reasoned was a compensation for the feelings of excessive responsibility as well as the loss of the exclusive attention of their parents.

This was followed by What Life Could Mean to You (1931), a plea for co-operation in a world experiencing great conflict: "We face three problems: how to find an occupation which will enable us to survive under the limitations set by the nature of the earth; how to find a position among our fellows, so that we may cooperate and share the benefits of cooperation; how to accommodate ourselves to the fact that we live in two sexes and that the continuance and furtherance of mankind depends upon our love-life."

Adler argued that in the early stages of our existence we had to co-operate for survival: "It was only because men learned to cooperate that we could make the great discovery of the division of labor; a discovery which is the chief security for the welfare of mankind. To preserve human life would not be possible if each individual attempted to wrest a living from the earth by himself with no cooperation and no results of cooperation in the past. Through the division of labour we can use the results of many different kinds of training and organize many different abilities so that all of them contribute to the common welfare and guarantee relief from insecurity and increased opportunity for all the members of society."

Alfred Adler was a regular visitor to America and in 1929 he was appointed visiting Professor at Columbia University. In 1932 he became chair of medical psychology at Long Island Medical College. After his lectures he worked at his clinic, which was opposite the university. In one letter he said he gave regular public lectures to large audiences. Although he worked mainly in America he spent most of his summer vacations in Vienna.

Austria, like the rest of Europe, suffered greatly during the Great Depression. In 1932, almost 470,000 people, nearly 22 per cent of Austria's labour force, were out of work. By the following year unemployment reached an unprecedented peak with 580,000, or 27 per cent. Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss governed under emergency powers and assumed dictatorial powers. This included banning all political parties and closing down the Austrian parliament.

On 30th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Germany's chancellor and over the next few months he banned opposition political parties, free speech, independent cultural organizations and universities and the rule of law. Anti-Semitism became government policy and German Jews, including the psychologists, Erich Fromm, Max Eitingon and Ernst Simmel, left the country. Sigmund Freud wrote to his nephew in Manchester that "life in Germany has become impossible."

Two of Adler's children, Kurt and Alexandra both worked in the field of psychiatry. Alexandra was one of the first women to practice neurology in Austria. She was in charge of a child guidance centre in Vienna until it was eventually closed down by Chancellor Dollfuss. Alfred and Raissa Adler, were both active in the socialist movement and fearing arrest the family moved to the United States in 1935. Alexandra was immediately offered a position as a neurology instructor at the Harvard Medical School. However, as no women were given regular faculty posts, she was added to the research staff with automatically renewable annual appointments.