On this day on 25th May

On this day in 1537 Margaret Cheyney was burnt at the stake at Smithfield for her role in the Pilgrimage of Grace. Margaret Cheyney was born in about 1500. It is believed that she was the illegitimate daughter of Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham. She married William Cheyney and after his death she became the mistress of John Bulmer. (1) Bulmer was a large landowner in Yorkshire. After his wife, Anne Bigod Bulmer died, the couple established a home at Lastingham, near Pickering. Sharon L. Jansen believes that the couple married in 1534 and she was known locally as Lady Bulmer. Charles Wriothesley described her as being "beautiful".

On 28th September 1536, the King's commissioners for the suppression of monasteries arrived to take possession of Hexham Abbey and eject the monks. They found the abbey gates locked and barricaded. "A monk appeared on the roof of the abbey, dressed in armour; he said that there were twenty brothers in the abbey armed with guns and cannon, who would all die before the commissioners should take it." The commissioners retired to Corbridge, and informed Thomas Cromwell of what had happened.

This was followed by other acts of rebellion against the dissolution of the monasteries. A lawyer, Robert Aske, eventually became leader of the rebellion in Yorkshire. People joined what became known as the Pilgrimage of Grace for a variety of different reasons. Derek Wilson, the author of A Tudor Tapestry: Men, Women & Society in Reformation England (1972) has argued: "It would be incorrect to view the rebellion in Yorkshire, the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace, as purely and simply an upsurge of militant piety on behalf of the old religion. Unpopular taxes, local and regional grievances, poor harvests as well as the attack on the monasteries and the Reformation legislation all contributed to the creation of a tense atmosphere in many parts of the country".

Within a few days, 40,000 men had risen in the East Riding and were marching on York. Aske called on his men to take an oath to join "our Pilgrimage of Grace" for "the commonwealth... the maintenance of God's Faith and Church militant, preservation of the King's person and issue, and purifying of the nobility of all villein's blood and evil counsellors, to the restitution of Christ's Church and suppression of heretics' opinions". Aske published a declaration obliging "every man to be true to the king's issue, and the noble blood, and preserve the Church of God from spoiling".

John Bulmer later joined the rebellion. However, he claimed that he had only became a member of the Pilgrimage of Grace under the threat of having his home burned down. However, he soon became one of the leaders and was one of those involved in peace negotiations with Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk. As a result of these discussions, Robert Aske, went to London to have discussions with Henry VIII.

Sharon L. Jansen, the author of Dangerous Talk and Strange Behaviour: Women and Popular Resistance to the Reforms of Henry VIII (1996) points out that there is no evidence that Margaret Cheyney was a member of the Pilgrimage of Grace. The fact that she was heavily pregnant at the time makes it even more unlikely. The boy, named John, was born in January 1536.

Robert Aske spent the Christmas holiday with Henry VIII at Greenwich Palace. When they first met Henry told Aske: "Be you welcome, my good Aske; it is my wish that here, before my council, you ask what you desire and I will grant it." Aske replied: "Sir, your majesty allows yourself to be governed by a tyrant named Cromwell. Everyone knows that if it had not been for him the 7,000 poor priests I have in my company would not be ruined wanderers as they are now." Henry gave the impression that he agreed with Aske about Thomas Cromwell and asked him to prepare a history of the previous few months. To show his support he gave him a jacket of crimson silk.

While in London another rebellion broke out in the East Riding. It was led by Sir Francis Bigod who accused Aske of betraying the Pilgrimage of Grace. Aske agreed to return to Yorkshire and assemble his men to defeat Bigod. He then joined up with Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and his army made up of 4,000 men. Bigod was easily defeated and after being captured on 10th February, 1537, was imprisoned in Carlisle Castle.

On 24th March, 1537, Robert Aske and Thomas Darcy were asked by the Duke of Norfolk to return to London in order to have a meeting with Henry VIII. They were told that the King wanted to thank them for helping to put down the Bigod rebellion. On their arrival they were both arrested and sent to the Tower of London. Aske was charged with renewed conspiracy after the pardon.

When news reached John Bulmer and Margaret Cheyney in Lastingham about what had happened to Aske and Darcy, Bulmer apparently told a friend that he would rather die in battle in Yorkshire than as a prisoner in London. They discussed the possibility of him fleeing to Scotland. Their parish priest later recalled that if Bulmer left the country on his own she "feared that she should be parted from him forever". Apparently he stated "Pretty Peg, I will never forsake thee." According to Geoffrey Moorhouse: "Others heard him say that he would rather be put on the rack than be parted from his wife. For her part, she vowed that she would rather be torn to pieces than go to London, and she begged him to get a ship that would take them and their three-month-old son to the safety of Scotland."

The government later claimed that Margaret suggested that John Bulmer should start another uprising. It was said "she enticed Sir John Bulmer to raise the commons again" and that "Margaret counselled him to flee the realm (if the commons would not rise) than that he and she should be parted". John Bulmer then contacted several local landowners to discuss his plans. At least two of the men approached, Thomas Francke and Gregory Conyers, told Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk about the planned uprising by Bulmer.

John Bulmer and Margaret Cheyney were arrested in early April, 1537. They were taken to London and were tortured. "We have no record of Margaret's confession, either, though it was doubtless extracted, but Bulmer refused to say anything in his that would implicate her and he pleaded guilty to the treason charge, possibly in the forlorn hope that this would exonerate her. Both of them, in fact, originally pleaded not guilty before changing their minds while the jury was actually considering its verdict and one view is that they did so because they had been promised the King's mercy if they admitted their guilt. Bulmer referred to Cheyney as his wife and nothing else right up to the end, much to the irritation of his accusers and the judge."

Margaret Cheyney was found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. Madeleine Dodds and Ruth Dodds, the authors of The Pilgrimage of Grace (1915) have speculated on the reasons for this. They argued that she "committed no overt act of treason; her offences were merely words and silence". They believed that Henry VIII wanted to use the case of Cheyney as an example to others. "There can be no doubt that many women were ardent supporters of the Pilgrimage.... Lady Bulmer's execution... was an object-lesson to husbands... to teach them to distrust their wives."

Sharon L. Jansen agrees with this point of view: "Margaret Cheyney's sexual power was suspect; women like her could lure their husbands into danger. Men needed to submit to their princes, and they also needed to control their wives, their mothers, their daughters, their female servants. Margaret Cheyney had violated the contemporary notion that wives should be chaste, silent, and obedient, and her death could certainly have been intended as a warning about the proper behaviour of women."

On the 25th May, 1537, John Bulmer was tied to a hurdle and dragged through the streets of London. Bulmer was taken to Tyburn and was hanged, almost to the point of death, revived, castrated, disembowelled, beheaded and quartered (his body was chopped into four pieces). Later that day Margaret Cheyney was burnt to death at Smithfield.

On this day in 1780 Josiah Wedgwood writes letter to Thomas Bentley on universal suffrage. "I wish every success to the Society for Constitutional Information and if I was upon the spot should gladly not confine myself to wishes only. If at this distance I can in any way promote their truly patriotic designs, either by my money or my services, they are both open to you to command as you please. I rejoice to hear that the Duke of Richmond and Lord Selbourne are friends of annual parliaments. I agree with Major Cartwight "that every member of the state must either have a vote or be a slave".

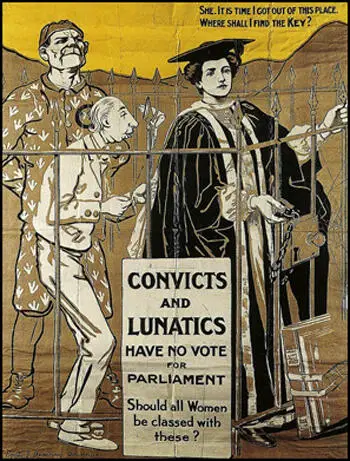

On this day in 1842 Helen Blackburn, the daughter of a civil engineer, was born on Valentia Island, off the south-west coast of Ireland. A talented artist, she had to give up by the age of 21 because of deteriorated eyesight.

In 1872 she joined the Central Society for Women's Suffrage. By 1874 she became secretary of the executive committee of the organisation. She also became a regular contributor and eventual editor of the Englishwoman's Review.

Blackburn became secretary of the Bristol and West of England Suffrage Society and in 1880 organised a large demonstration in Bristol in favour of women's suffrage. During this period she was described by Frances Balfour as an important figure in the struggle for the vote: "On the table amid her work was a small glass, in which stood a single flower, or sprig of green, and not infrequently a little bit of shamrock, in strange outward contrast to the large uncouth figure of Miss Blackburn, her shortsighted eyes always close to the papers she was working at... Her face was greatly marred by long illness, most patiently borne, but through its plainness there shone the countenance of a great soul.... Miss Blackburn was a born chronicler and antiquarian.. Her knowledge and experience was at everyone's disposal."

As Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999), has pointed out: "Helen Blackburn was a strenuous opponent of legislative restrictions on the labour of women, and contended that what women wanted were more and not fewer opportunities of earning their living." In 1885 she joined Jessie Boucherett in forming the Labour Defence Association to protect workers from restrictive legislation.

In 1887 seventeen of these individual groups joined together to form the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Lydia Becker was elected as president. Three years later, when Becker died, Millicent Fawcett became the new leader of the organisation. Blackburn was a leading figure in the NUWSS until 1895 when she retired from active duty to look after her aged father.

Blackburn now concentrated on her research and joined with Jessie Boucherett to write, The Condition of Working Women (1896). In 1902 she published Women's Suffrage: A Record of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the British Isles.

Helen Blackburn died on 11th January 1903.

On this day in 1850 Charles Dickens describes a visit to the workhouse in Household Words.

A few Sundays ago, I formed one of the congregation assembled in the chapel of a large metropolitan Workhouse. With the exception of the clergyman and clerk, and a very few officials, there were none but paupers present. The children sat in the galleries; the women in the body of the chapel, and in one of the side aisles; the men in the remaining aisle. The service was decorously performed, though the sermon might have been much better adapted to the comprehension and to the circumstances of the hearers.

The usual supplications were offered, with more than the usual significancy in such a place, for the fatherless children and widows, for all sick persons and young children, for all that were desolate and oppressed, for the comforting and helping of the weak-hearted, for the raising-up of them that had fallen; for all that were in danger, necessity, and tribulation. The prayers of the congregation were desired "for several persons in the various wards, dangerously ill"; and others who were recovering returned their thanks to Heaven.

Among this congregation, were some evil-looking young women, and beetle-browed young men; but not many - perhaps that kind of characters kept away. Generally, the faces (those of the children excepted) were depressed and subdued, and wanted colour. Aged people were there, in every variety. Mumbling, blear-eyed, spectacled, stupid, deaf, lame; vacantly winking in the gleams of sun that now and then crept in through the open doors, from the paved yard; shading their listening ears, or blinking eyes, with their withered hands, poring over their books, leering at nothing, going to sleep, crouching and drooping in corners. There were weird old women, all skeleton within, all bonnet and cloak without, continually wiping their eyes with dirty dusters of pocket-handkerchiefs; and there were ugly old crones, both male and female, with a ghastly kind of contentment upon them which was not at all comforting to see. Upon the whole, it was the dragon, Pauperism, in a very weak and impotent condition; toothless, fangless, drawing his breath heavily enough, and hardly worth chaining tip.

When the service was over, I walked with the humane and conscientious gentleman whose duty it was to take that walk, that Sunday morning, through the little world of poverty enclosed within the workhouse walls. It was inhabited by a population of some fifteen hundred or two thousand paupers, ranging from the infant newly born or not yet come into the pauper world, to the old man dying on his bed.

In a room opening from a squalid yard, where a number of listless women were lounging to and fro, trying to get warm in the ineffectual sunshine of the tardy May morning - in the "Itch Ward", not to compromise the truth - a woman such as Hogarth has often drawn was hurriedly getting on her gown, before a dusty fire. She was the nurse, or wardswoman, of that insalubrious department - herself a pauper - flabby, raw-boned, untidy - unpromising and coarse of aspect as need be. But, on being spoken to about the patients whom she had in charge, she turned round, with her shabby gown half on, half off, and fell a crying with all her might. Not for show, not querulously, not in any mawkish sentiment, but in the deep grief and affliction of her heart; turning away her dishevelled head: sobbing most bitterly, wringing her hands, and letting fall abundance of great tears, that choked her utterance. What was the matter with the nurse of the itch-ward? Oh, "the dropped child" was dead! Oh, the child that was found in the street, and she had brought up ever since, had died an hour ago, and see where the little creature lay, beneath his cloth! The dear, the pretty dear!

The dropped child seemed too small and poor a thing for death to be in earnest with, but death had taken it; and already its diminutive form was neatly washed, composed, and stretched as if in sleep upon a box. I thought I heard a voice from Heaven saying, It shall be well for thee, O nurse of the itch-ward, when some less gentle pauper does those offices to thy cold form, that such as the dropped child are the angels who behold my Father's face!

In another room, were several ugly old women crouching, witch-like, round a hearth, and chattering and nodding, after the manner of the monkeys. "All well here? And enough to eat?" A general chattering and chuckling; at last an answer from a volunteer. "Oh yes gentleman! Bless you gentleman! Lord bless the parish of St. So-and-So! It feed the hungry, Sir, and give drink to the thirsty, and it warm them which is cold, so it do, and good luck to the parish of St. So-and-So, and thankee gentleman!" Elsewhere, a party of pauper nurses were at dinner. "How do you get on?" "Oh pretty well Sir! We works hard, and we lives hard - like the sodgers!"

In another room, a kind of purgatory or place of transition, six or eight noisy madwomen were gathered together, under the superintendence of one sane attendant. Among them was a girl of two or three and twenty, very prettily dressed, of most respectable appearance, and good manners, who had been brought in from the house where she had lived as domestic servant (having, I suppose, no friends), on account of being subject to epileptic fits, and requiring to be removed under the influence of a very bad one. She was by no means of the same stuff, or the same breeding, or the same experience, or in the same state of mind, as those by whom she was surrounded; and she pathetically complained, that the daily association and the nightly noise made her worse, and was driving her mad - which was perfectly evident. The case was noted for enquiry and redress, but she said she had already been there for some weeks.

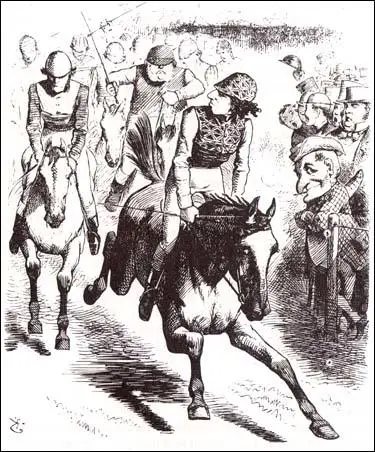

On this day in 1867 John Tenniel publishes cartoon on the Reform Bill.

John Tenniel, Punch Magazine (25th May, 1867)

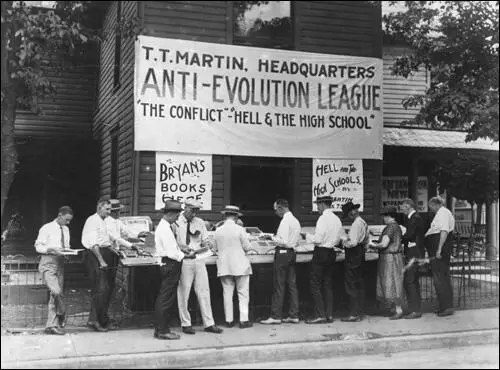

On this day in 1925 John T. Scopes is indicted for teaching human evolution in Tennessee. In the 1920s, the popular politician, William Jennings Bryan, began a campaign to bring an end to the teaching of evolution in schools. Bryan argued in 1922: " Now that the legislatures of the various states are in session, I beg to call attention of the legislators to a much needed reform, viz., the elimination of the teaching of atheism and agnosticism from schools, colleges and universities supported by taxation. Under the pretense of teaching science, instructors who draw their salaries from the public treasury are undermining the religious faith of students by substituting belief in Darwinism for belief in the Bible. Our Constitution very properly prohibits the teaching of religion at public expense. The Christian church is divided into many sects, Protestant and Catholic, and it is contrary to the spirit of our institutions, as well as to the written law, to use money raised by taxation for the propagation of sects. In many states they have gone so far as to eliminate the reading of the Bible, although its morals and literature have a value entirely distinct from the religious interpretations variously placed upon the Bible."

Tennessee governor Austin Peay, agreed with Bryan and in 1925 he passed what became known as the Butler Act. This prohibited public school teachers from denying the Biblical account of man's origin. The law also prevented the teaching of the evolution of man from what it referred to as lower orders of animals in place of the Biblical account.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) announced that it would finance a test case challenging the constitutionality of this measure. John Thomas Scopes, a teacher at Rhea County High School in Dayton, Tennessee, was approached by engineer and geologist George Rappleyea, and asked if he would be willing to teach evolution at the Rhea County High School. Scopes agreed and was arrested on 5th May, 1925. America's most famous criminal lawyer, Clarence Darrow, offered to defend Scopes without a fee. Leading the prosecution was Arthur Thomas Stewart, the District Attorney and he was joined by William Jennings Bryan, who was financed by the World Christian Fundamental Association.

The trial began in Dayton on 11th July, 1925. Over 100 journalists arrived in the town to report on the trial. The Chicago Tribune installed its own radio transmitter and it became the first trial in American history to be broadcast to the nation. Three schoolboys testified that they had been present when Scopes had taught evolution in their school. When the judge, John T. Raulston, refused to allow scientists to testify on the truth of evolution, Clarence Darrow called William Jennings Bryan to the witness stand. This became the highlight of the 11 day trial and many independent observers believed that Darrow successfully exposed the flaws in Bryan's arguments during the cross-examination.

In his closing speech Bryan pointed out: "Let us now separate the issues from the misrepresentations, intentional or unintentional, that have obscured both the letter and the purpose of the law. This is not an interference with freedom of conscience. A teacher can think as he pleases and worship God as he likes, or refuse to worship God at all. He can believe in the Bible or discard it; he can accept Christ or reject Him. This law places no obligations or restraints upon him. And so with freedom of speech, he can, so long as he acts as an individual, say anything he likes on any subject. This law does not violate any rights guaranteed by any Constitution to any individual. It deals with the defendant, not as an individual, but as an employee, official or public servant, paid by the State, and therefore under instructions from the State.... It need hardly be added that this law did not have its origin in bigotry. It is not trying to force any form of religion on anybody. The majority is not trying to establish a religion or to teach it - it is trying to protect itself from the effort of an insolent minority to force irrellgion upon the children under the guise of teaching science."

Bryan went on to argue: "Evolution is not truth; it is merely a hypothesis - it is millions of guesses strung together. It had not been proven in the days of Darwin - he expressed astonishment that with two or three million species it had been impossible to trace any species to any other species - it had not been proven in the days of Huxley, and it has not been proven up to today. It is less than four years ago that Professor Bateson came all the way from London to Canada to tell the American scientists that every effort to trace one species to another had failed - every one. He said he still had faith in evolution but had doubts about the origin of species. But of what value is evolution if it cannot explain the origin of species? While many scientists accept evolution as if it were a fact, they all admit, when questioned, that no explanation has been found as to how one species developed into another."

The jury found John Thomas Scopes guilty and the judge fined him $100. A successful film, Inherit the Wind (1960) was loosly based on the trial.

On this day in 1913 Richard Dimbleby was born in Richmond-upon-Thames. After attending Mill Hill School he began his career with the family newspaper, the Richmond and Twickenham Times in 1931. He later worked for the Bournemouth Echo and Advertisers Weekly.

In 1936 Dimbleby joined the British Broadcasting Corporation as a news reporter. In 1939 he accompanied the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to France.

After Dunkirk Dimbleby reported from the frontline in Egypt and Greece. He also flew 20 missions with RAF Bomber Command. In 1945 he was the first reporter to enter Belsen Concentration Camp.

After the war Dimbleby became the main commentator on state occasions. This included the funerals of George VI and Winston Churchill. He was also managing director of the family newspaper business (1954-65) and presenter of BBC's Panorama (1955-63). Richard Dimbleby died of cancer in London on 22nd December 1965.

On this day in 1916 Siegfried Sassoon described a patrol into No Man's Land in his diary.

Twenty-seven men with faces blackened and shiny - with hatchets in their belts, bombs in pockets, knobkerries - waiting in a dug-out in the reserve line. At 10.30 they trudge up to Battalion H.Q. splashing through the mire and water in a chalk trench, while the rain comes steadily down. Then up to the front-line. In a few minutes they have gone over and disappeared into the rain and darkness.

I am sitting on the parapet listening for something to happen - five, ten, nearly fifteen minutes - not a sound - nor a shot fired - and only the usual flare-lights. Then one of the men comes crawling back; I follow him to our trench and he tells me that they can't get through. They are all going to throw a bomb and retire.

A minute or two later a rifle-shot rings out and almost simultaneously several bombs are thrown by both sides; there are blinding flashes and explosions, rifle-shots, the scurry of feet, curses and groans, and stumbling figures loom up and scramble over the parapet - some wounded. When I've counted sixteen in, I go forward to see how things are going. Other wounded men crawl in; I find one hit in the leg; he says O'Brien is somewhere down the crater badly wounded. They are still throwing bombs and firing at us: the sinister sound of clicking bolts seem to be very near; perhaps they have crawled out of their trench and are firing from behind the advanced wire.

At last I find O'Brien down a deep (about twenty-five feet) and precipitous crater. He is moaning and his right arm is either broken or almost shot off: he is also hit in the right leg. Another man is with him; he is hit in the right arm. I leave them there and get back to the trench for help, shortly afterwards Lance-Corporal Stubbs is brought in (he has had his foot blown off). I get a rope and two more men and go back to O'Brien, who is unconscious now. With great difficulty we get him half-way up the face of the crater; it is now after one o'clock and the sky is beginning to get lighter. I make one more journey to our trench for another strong man and to see to a stretcher being ready. We get him in, and it is found that he has died, as I had feared.

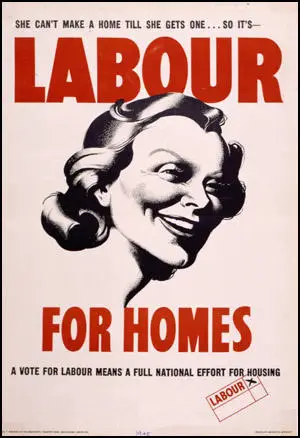

On this day in 1945 Aneurin Bevan comments on a possible Labour Party victory in the 1945 General Election: ."At last, the deadly political frustration is ended; at last the unnatural alliance is broken between left and right, between Socialism and Reaction, in other words between forces which on every single issue (bar only the defeat of Nazi Germany) proceed from opposite principles and stand for opposite policies... The sooner the election is held, the sooner we shall be able to get rid of the Tories and begin in earnest with the solution of the tremendous tasks before us."

On this day in 1948 Witold Pilecki, Polish officer and Resistance leader was executed. Witold Pilecki was born in Poland in 1901. When the German Army invaded the country in September, 1939, Pilecki joined the Tajna Armia Polska, the Secret Polish Army.

When Pilecki discovered the existence of Auschwitz, he suggested a plan to his senior officers. Pilecki argued he should get himself arrested and sent to the concentration camp. He would then send out reports of what was happening in the camp. Pilecki would also explore the possibility of organizing a mass break-out.

Pilecki's colonel eventually agreed and after securing a false identity as Tomasz Serafinski, he arranged to be arrested in September, 1940. As expected he was sent to Auschwitz where he became prisoner 4,859. His work consisted of building more huts to hold the increased numbers of prisoners.

Pilecki soon discovered the brutality of the Schutz Staffeinel (SS) guards. When one man managed to escape on 28th October 1940, all the prisoners were forced to stand at attention on the parade-ground from noon till nine in the evening. Anyone who moved was shot and over 200 prisoners died of exposure. Pilecki was able to send reports back to the Tajna Armia Polska explaining how the Germans were treating their prisoners. This information was then sent to the foreign office in London.

In 1942 Pilecki discovered that new windowless concrete huts were being built with nozzles in their ceilings. Soon afterwards he heard that that prisoners were being herded into these huts and that the nozzles were being used to feed cyanide gas into the building. Afterwards the bodies were taken to the building next door where they were cremated.

Pilecki got this information to the Tajna Armia Polska who passed it onto the British foreign office. This information was then passed on to the governments of other Allied countries. However, most people who saw the reports refused to believe them and dismissed the stories as attempts by the Poles to manipulate the military strategy of the Allies.

In the autumn of 1942, Jozef Cyrankiewicz, a member of the Polish Communist Party, was sent to Auschwitz. Pilecki and Cyrankiewicz worked closely together in organizing a mass breakout. By the end of 1942 they had a group of 500 ready to try and overthrow their guards.

Four of the inmates escaped on their own on 29th December, 1942. One of these men, a dentist called Kuczbara, was caught and interrogated by the Gestapo. Kuczbara was one of the leaders of Pilecki's group and so when he heard the news he realized that it would be only a matter of time before the SS realized that he had been organizing these escape attempts.

Witold Pilecki had already arranged his escape route and after feigning typhus, he escaped from the hospital on 24th April, 1943. After hiding in the local forest, Pilecki reached his unit of the Tajna Armia Polska on 2nd May. He returned to normal duties and fought during the Warsaw Uprising in the summer of 1944. Although captured by the German Army he was eventually released by Allied troops in April, 1945.

After the Second World War Pilecki went to live in Poland.The Polish Secret Police had him executed in 1948. It is believed that this was a result of his anti-communist activities.