On this day on 19th August

On this day in 1819 Thomas Barnes, the editor of The Times, condemns the Peterloo Massacre

"Whatever an observant mind may suspect as to the real objects of the few (Hunt and Co.) who thus played upon the passions and misfortunes of a suffering multitude - all such considerations, all such suspicions, sink to nothing before the dreadful fact, that nearly a hundred of the King's unarmed subjects have been sabred by a body of cavalry in the streets of a town of which most of them were inhabitants, and in the presence of those Magistrates whose sworn duty it is to protect and preserve the life of the meanest Englishmen."

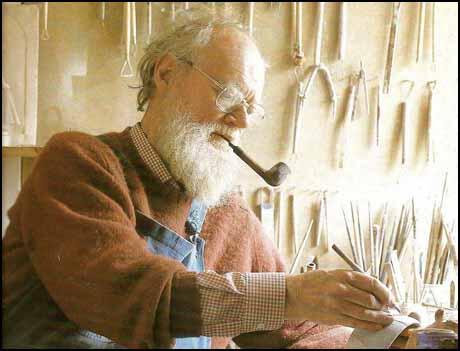

On this day in 1910 Quentin Bell, the younger son of Clive Heward Bell and his wife, Vanessa Bell, the daughter of Leslie Stephen, and the sister of Virginia Woolf, was born on 19th August 1910. He was brought up in the family home at 46 Gordon Square and at Charleston Farmhouse, near Firle. Like his brother, Julian Bell, he was educated at Leighton Park School, the Quaker boarding-school in Reading.

A talented artist, Bell left school at seventeen and went on a tour of central European galleries with Roger Fry, the famous art critic. He spent periods of time painting in both Paris and Rome.

In 1933 Bell was forced to spend seven months in a sanatorium in Switzerland followed by convalescence near Monaco. In 1935 he returned to Italy and had his first exhibition at the Mayor Gallery. But later that year he decided to become a potter rather than a painter and enrolled himself at Burslem School of Art. While living in Stoke-on-Trent he became an active member of the Labour Party. Eventually he set up a studio at Charleston Farmhouse, where his artist mother Vanessa Bell and her former lover, Duncan Grant, also worked.

According to Leonard Woolf, Bell became a member of the Bloomsbury Group: "in the 1920's and 1930's when Old Bloomsbury narrowed and widened into a newer Bloomsbury, it lost through death Lytton (Strachey) and Roger (Fry) and added to its numbers, Julian, Quentin and Angelica Bell, and David (Bunny) Garnett."

His parents had been pacifists during the First World War. Bell was willing to joined the British Army after the outbreak of the Second World War but as was in poor health he was rejected on medical grounds. He therefore worked on the farm owned by John Maynard Keynes near Firle. He also joined his mother Vanessa Bell and her former lover, Duncan Grant, in providing wall-paintings at Berwick Church, that were completed in 1943. He was also employed by David Garnett in the political warfare department of the Foreign Office.

In 1947 Bell published his first major book, On Human Finery, a study of the history of fashion. He married the art historian, Anne Olivier Popham, on 16th February 1952. Soon afterwards he became a senior lecturer at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne. He moved to Leeds Art School in 1959. He also taught at Slade Art School and Hull Art School before in 1967 becoming professor of the history and theory of art at Sussex University.

Bell had been a member of the Bloomsbury Circle, a group that included Virginia Woolf, Vanessa Bell , Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, Adrian Stephen, E. M. Forster, Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Desmond MacCarthy, Mary MacCarthy, Duncan Grant, Arthur Waley and Saxon Sydney-Turner. He was therefore in a good position to publish Bloomsbury (1968) and a two volume biography of his aunt, in his much acclaimed Virginia Woolf: A Biography (1972).

According to his biographer, Charles Saumarez Smith: "After retiring from his post at Sussex in 1975, Bell was able to spend more time and energy on his pottery. In 1985 he and his wife, Olivier, moved to a smaller house next door to the park in Firle and each morning he would wake up early and disappear to his kiln, only emerging for gin and ginger beer in the evening. He undertook a mixture of work, some rough, painted plates and mugs, which he saw as belonging to an artisan tradition, but also more ambitious ceramic sculpture. Neither style fitted comfortably within the work of contemporaries, as his pots were too utilitarian to be regarded as art and his ceramic sculpture too conventionally figurative. But this in no way deterred him from turning out a great amount of work which was both vigorous and affordable, a crossover between the Omega workshop and folk art."

Bell helped establish the Charleston Trust, which was responsible for saving his mother's house. Other books included a novel, The Brandon Papers (1985), a collection of essays and lectures in Bad Art (1989), and a series of character sketches, Elders and Betters (1995).

Quentin Bell died at his home, 81 Heighton Street, Firle, East Sussex, on 16th December 1996.

On this day in 1914 it is agreed to form Pals Battalions to fight in the First World War. Lord Kitchener was appointed Secretary for War in August 1914. His main task was to persuade men to join the British Army. At a meeting on the 19th August it was suggested by Sir Henry Rawlinson that men would be more willing to enlist if they knew they would serve with people they knew. Rawlinson asked his friend, Robert White, to raise a battalion composed of men who worked in the City. White opened a recruiting office in Throgmorton Street and in the first two hours, 210 City workers joined the army. Six days later, the Stockbrokers' Battalion, as it became known, had 1,600 men.

When Lord Edward Derby heard about Robert White's success he decided to form a battalion in Liverpool. Derby opened the recruitment office on 28th August 1914 and by the end of the day had signed up 1,500 men. It was Derby who first used the term a "battalion of pals" to describe men who had been recruited locally.

When Lord Kitchener heard about Derby's success in Liverpool he decided to encourage towns and villages all over Britain to organise recruitment campaigns based on the promise that the men could serve with friends, neighbours and workmates. These units were raised by local authorities, industrialists or committees of private citizens. By the end of September over fifty towns in Britain had formed pals battalions. The larger towns and cities were able to form more than one battalion. Manchester and Hull had four, Liverpool, Birmingham and Glasgow had three and many more were able to raise at least two battalions. In Gasgow one battalion was drawn from the drivers, conductors, mechanics and labourers of the city's Tramways Department.

In August 1914 several young men who had attended Winteringham Secondary School in Grimsby suggested to the former headmaster that he should form a battalion from his former pupils. He agreed and by the end of October he had recruited over 1,000 members into what they called the 'Grimsby Chums'. Other schools, including five of Britain's leading public schools, also formed battalions.

West Ham United supporters also formed their own Pals Battalion. The 13th (Service) Battalion (West Ham Battalion) were part of the Essex Regiment. In his book War Hammers: The Story of West Ham United During the First World War (2006), Brian Belton argues that the battle cry of the West Ham Pals was "Up the Hammers" and "Up the Irons." They saw action at the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Cambrai. The war took a terrible toll on these men. Elliott Taylor, the author of Up The Hammers!: the West Ham Battalion in the Great War (2012), has argued "Roughly one quarter of the original battalion volunteers were killed and nearly half were returned to UK with severe injuries."

In September Mrs. E. Cunliffe-Owen gained permission from Lord Kitchener to raise a sportsman's battalion. This battalion included two famous cricketers and the lightweight boxing champion of England. Later, a group of friends formed a footballers' battalion.

Pals battalions made up a significant proportion of Kitchener's army. Between September 1914 and June 1916, a total of 351 infantry battalions were raised by the War Office through the traditional channels whereas 643 battalions were raised locally.

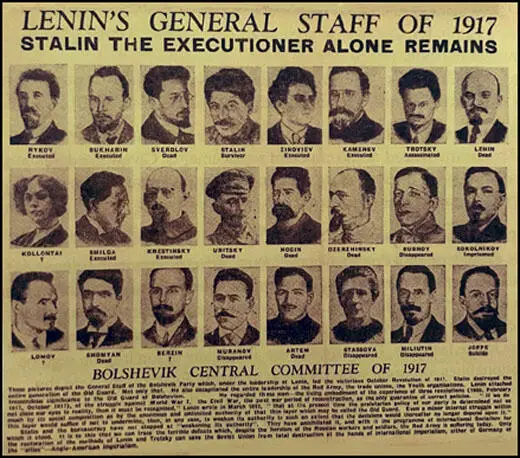

On this day in 1936 the Great Purge begins with the first of the Soviet Show Trials. The first ever trial involved Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Ivan Smirnov and thirteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin. Yuri Piatakov accepted the post of chief witness "with all my heart." Max Shachtman pointed out: "The official indictment charges a widespread assassination conspiracy, carried on these five years or more, directed against the head of the Communist party and the government, organized with the direct connivance of the Hitler regime, and aimed at the establishment of a Fascist dictatorship in Russia. And who are included in these stupefying charges, either as direct participants or, what would be no less reprehensible, as persons with knowledge of the conspiracy who failed to disclose it?"

The men made confessions of their guilt. Lev Kamenev said: "I Kamenev, together with Zinoviev and Trotsky, organised and guided this conspiracy. My motives? I had become convinced that the party's - Stalin's policy - was successful and victorious. We, the opposition, had banked on a split in the party; but this hope proved groundless. We could no longer count on any serious domestic difficulties to allow us to overthrow. Stalin's leadership we were actuated by boundless hatred and by lust of power."

Gregory Zinoviev also confessed: "I would like to repeat that I am fully and utterly guilty. I am guilty of having been the organizer, second only to Trotsky, of that block whose chosen task was the killing of Stalin. I was the principal organizer of Kirov's assassination. The party saw where we were going, and warned us; Stalin warned as scores of times; but we did not heed these warnings. We entered into an alliance with Trotsky."

Most journalists covering the trial were convinced that the confessions were statements of truth. The Observer reported: "It is futile to think the trial was staged and the charges trumped up. The government's case against the defendants (Zinoviev and Kamenev) is genuine." The The New Statesman commented: "Very likely there was a plot. We complain because, in the absence of independent witnesses, there is no way of knowing. It is their (Zinoviev and Kamenev) confession and decision to demand the death sentence for themselves that constitutes the mystery. If they had a hope of acquittal, why confess? If they were guilty of trying to murder Stalin and knew they would be shot in any case, why cringe and crawl instead of defiantly justifying their plot on revolutionary grounds? We would be glad to hear the explanation."

Anna Louise Strong, of the Moscow Daily News, defended the Great Purge: "The key to the terror, most probably, in actual, extensive penetration of the GPU by a Nazi fifth column, in many actual plots and in the impact of these on a highly suspicious man who saw his own assassination plotted and believed he was saving the Revolution by drastic purge... Stalin engineered the country's modernization ruthlessly, for he was born in a ruthless land and endured ruthlessness from childhood. He engineered suspiciously, for he had been five times exiled and must have been often betrayed. He condoned, and even authorized outrageous acts of the political police against innocent people, but so far no evidence is produced that he consciously framed them."

Walter Duranty was the New York Times journalist based in Moscow. He wrote in the The New Republic that while watching the trial he came to the conclusion "that the confessions are true". Based on these comments the editor of the journal argued: "Some commentators, writing at a long distance from the scene, profess doubt that the executed men (Zinoviev and Kamenev) were guilty. It is suggested that they may have participated in a piece of stage play for the sake of friends or members of their families, held by the Soviet government as hostages and to be set free in exchange for this sacrifice. We see no reason to accept any of these laboured hypotheses, or to take the trial in other than its face value. Foreign correspondents present at the trial pointed out that the stories of these sixteen defendants, covering a series of complicated happenings over nearly five years, corroborated each other to an extent that would be quite impossible if they were not substantially true. The defendants gave no evidence of having been coached, parroting confessions painfully memorized in advance, or of being under any sort of duress."

Leon Trotsky, who was living in exile in Mexico City, was furious with Duranty and described him as a "hypocritical psychologist" who tried to explain away the terrors of the regime with "glib and facile phrases." Trotsky condemned Joseph Stalin "for betraying socialism and dishonoring the revolution" and describing the leadership as being "dominated by a clique which holds the people in subjection by oppression and terror." The trial, Trotsky claimed was a "frame-up" that lacked "objectivity and impartiality" and volunteered to go before an international commission to prove his innocence."

In September, 1936, Stalin appointed Nikolai Yezhov as head of the NKVD, the Communist Secret Police. Yezhov quickly arranged the arrest of all the leading political figures in the Soviet Union who were critical of Stalin. The Secret Police broke prisoners down by intense interrogation. This included the threat to arrest and execute members of the prisoner's family if they did not confess. The interrogation went on for several days and nights and eventually they became so exhausted and disoriented that they signed confessions agreeing that they had been attempting to overthrow the government.

In January, 1937, Yuri Piatakov, Karl Radek, Grigori Sokolnikov, and fifteen other leading members of the Communist Party were put on trial. They were accused of working with Leon Trotsky in an attempt to overthrow the Soviet government with the objective of restoring capitalism. Robin Page Arnot, a leading figure in the British Communist Party, wrote: "A second Moscow trial, held in January 1937, revealed the wider ramifications of the conspiracy. This was the trial of the Parallel Centre, headed by Piatakov, Radek, Sokolnikov, Serebriakov. The volume of evidence brought forward at this trial was sufficient to convince the most sceptical that these men, in conjunction with Trotsky and with the Fascist Powers, had carried through a series of abominable crimes involving loss of life and wreckage on a very considerable scale."

Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996) has pointed out: "After they saw that Piatakov was ready to collaborate in any way required, they gave him a more complicated role. In the 1937 trials he joined the defendants, those whom he had meant to blacken. He was arrested, but was at first recalcitrant. Ordzhonikidze in person urged him to accept the role assigned to him in exchange for his life. No one was so well qualified as Piatakov to destroy Trotsky, his former god and now the Party's worst enemy, in the eyes of the country and the whole world. He finally agreed I to do it as a matter of 'the highest expediency,' and began rehearsals with the interrogators."

One of the journalists covering the trial, Lion Feuchtwanger, commented: "Those who faced the court could not possibly be thought of as tormented and desperate beings. In appearance the accused were well-groomed and well-dressed men with relaxed and unconstrained manners. They drank tea, and there were newspapers sticking out of their pockets... Altogether, it looked more like a debate... conducted in conversational tones by educated people. The impression created was that the accused, the prosecutor, and the judges were all inspired by the same single - I almost said sporting - objective, to explain all that had happened with the maximum precision. If a theatrical producer had been called on to stage such a trial he would probably have needed several rehearsals to achieve that sort of teamwork among the accused."

Yuri Piatakov and twelve of the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Karl Radek and Grigori Sokolnikov were sentenced to ten years. Feuchtwanger commented that Radek "gave the condemned men a guilty smile, as though embarrassed by his luck." Maria Svanidze, who was later herself to be purged by Joseph Stalin wrote in her diary: "They arrested Radek and others whom I knew, people I used to talk to, and always trusted.... But what transpired surpassed all my expectations of human baseness. It was all there, terrorism, intervention, the Gestapo, theft, sabotage, subversion.... All out of careerism, greed, and the love of pleasure, the desire to have mistresses, to travel abroad, together with some sort of nebulous prospect of seizing power by a palace revolution. Where was their elementary feeling of patriotism, of love for their motherland? These moral freaks deserved their fate.... My soul is ablaze with anger and hatred. Their execution will not satisfy me. I should like to torture them, break them on the wheel, burn them alive for all the vile things they have done."

On 14th July 1937, Walter Duranty wrote another article on the show-trials, The Riddle of Russia, for The New Republic. He argued that since November 1934, that agents working for Nazi Germany had infiltrated the ranks of the Soviet leadership, while Trotsky, like an exiled monarch, was the leader of the conspiracy to overthrow Stalin. Duranty went on to claim that this conspiracy had involved many men in the highest echelons of government. But now "their Trojan horse was broken, and its occupants destroyed."

James William Crowl, the author of Angels in Stalin's Paradise (1982 has argued: "Although Louis Fischer reserved judgment on the trials, Duranty vigorously defended them. According to him, Trotsky had created a spy network at the very time that Germany and Japan were spreading their own spy organizations in Russia. He explained that the two groups shared a hatred for Stalin, and fascist agents had cooperated with the Trotskyites in Kirov's assassination. The show-trials, Duranty insisted, had revealed the Trotskyite-fascist link beyond question. The trials showed just as clearly, he argued (on 14th July, 1937), that Stalin's arrest of thousands of these agents had spared the country from a wave of assassinations. Duranty charged that those who worried about the rights of the defendants or claimed that their confessions had been gained by drugs or torture, only served the interests of Germany and Japan."

The next show trials took place in March, 1938, and involved twenty-one leading members of the party. This included Nickolai Bukharin, Alexei Rykov, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky. They were accused of being involved with Leon Trotsky in a plot against Joseph Stalin and with spying for foreign powers. They were all found guilty and were either executed or died in labour camps.

Stalin now decided to purge the Red Army. Some historians believe that Stalin was telling the truth when he claimed that he had evidence that the army was planning a military coup at this time. Leopold Trepper, head of the Soviet spy ring in Germany, believed that the evidence was planted by a double agent who worked for both Stalin and Hitler. Trepper's theory is that the "chiefs of Nazi counter-espionage" led by Reinhard Heydrich, took "advantage of the paranoia raging in the Soviet Union," by supplying information that led to Stalin executing his top military leaders.

In June, 1937, Mikhail Tukhachevsky and seven other top Red Army commanders were charged with conspiracy with Germany. All eight were convicted and executed. All told, 30,000 members of the armed forces were executed. This included fifty per cent of all army officers.

The last stage of the terror was the purging of the NKVD. Stalin wanted to make sure that those who knew too much about the purges would also be killed. Stalin announced to the country that "fascist elements" had taken over the security forces which had resulted in innocent people being executed. He appointed Lavrenti Beria as the new head of the Secret Police and he was instructed to find out who was responsible. After his investigations, Beria arranged the executions of all the senior figures in the organization.

Walter Duranty always underestimated the number killed during the Great Purge. As Sally J. Taylor, the author of Stalin's Apologist: Walter Duranty (1990) has pointed out: "As for the number of resulting casualties from the Great Purge, Duranty's estimates, which encompassed the years from 1936 to 1939, fell considerably short of other sources, a fact he himself admitted. Whereas the number of Party members arrested is usually put at just above one million, Duranty's own estimate was half this figure, and he neglected to mention that of those exiled into the forced labor camps of the GULAG, only a small percentage ever regained their freedom, as few as 50,000 by some estimates. As to those actually executed, reliable sources range from some 600,000 to one million, while Duranty maintained that only about 30,000 to 40,000 had been killed."

On this day in 1957 David Bomberg died.

Bomberg was born in Birmingham on 5th December, 1890. He trained as a lithographer before studying painting in London at the Westminster School of Art (1908-10) and the Slade School of Art (1911-13). In 1913 he travelled to France where he met Modigliani and Picasso. Over the next few years his paintings combine abstract and Vorticist influences.

In 1917 the Canadian authorities commissioned Bomberg to paint a picture to celebrate an operation in which sappers successfully blew up a salient of the German defences at Saint-Eloi near Arras. His painting, Sappers at Work was rejected by the Canadian committee who criticised Bomberg's Futurism. Bomberg included himself in second version of the painting carrying a heavy beam on his shoulder, to illustrate the burden of working to order.

After the First World War Bomberg travelled widely, visiting Palestine (1923-27), Spain (1934-35), Morocco (1930), Greece (1930) and Russia (1933).

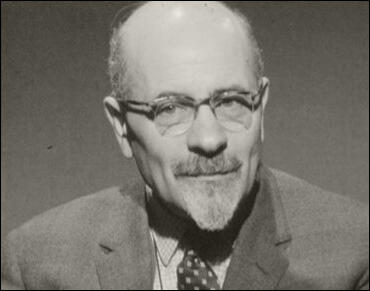

On this day in 1967 historian Isaac Deutscher died in Rome.

Isaac Deutscher was born in Cracow, Poland, on 3rd April, 1907. A journalist, he joined the Polish Communist Party in 1926. However, he was expelled in 1932 because he was critical of Joseph Stalin.

On the outbreak of the Second World War Deutscher moved to England and began writing for the The Observer. He also became chief European correspondent for the Economist.

Deutscher wrote several books about the Soviet Union including Stalin (1949), Soviet Trade Unions (1950), Russia after Stalin (1953), Trotsky: The Prophet Armed (1954), Heretics and Renegades (1955), Trotsky: The Prophet Unarmed (1959), The Great Contest (1960), Trotsky: The Prophet Outcast (1963) and Ironies of History, Essays on Contemporary Communism (1966).

Since his death books published include Lenin's Childhood (1970), The Unfinished Revolution: Russia 1917-1967(1974), Marxism in Our Time (1974), Soviet Trade Unions (1984), The Great Purges (1984) and Marxism, Wars and Revolutions: Essays from Four Decades (1984).