On this day on 7th January

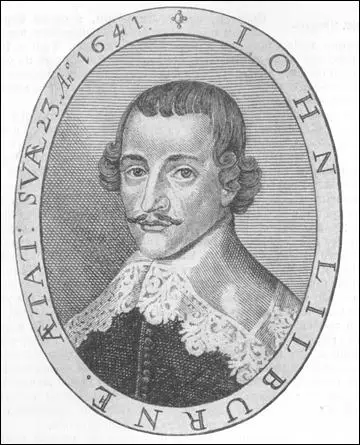

On this day in 1645 John Lilburne wrote a letter arguing for freedom of speech for religious dissents. During the English Civil War some radicals began writing and distributing pamphlets on soldiers' rights. Radicals such as Lilburne were unhappy with the way that the war was being fought. Whereas he hoped the conflict would lead to political change, this was not true of most of the Parliamentary leaders. "The generals themselves members of the titled nobility, were ardently seeking a compromise with the King. They wavered in their prosecution of the war because they feared that a shattering victory over the King would create an irreparable breach in the old order of things that would ultimately be fatal to their own position."

William Prynne, a leading Puritan critic of Charles I, became disillusioned with the increase of religious toleration during the war. In December, 1644, he published Truth Triumphing, a pamphlet that promoted church discipline. On 7th January, 1645, Lilburne wrote a letter to Prynne complaining about the intolerance of the Presbyterians and arguing for freedom of speech for all religious groups.

Lilburne's political activities were reported to Parliament. As a result, he was brought before the Committee of Examinations on 17th May, 1645, and warned about his future behaviour. Prynne and other leading Presbyterians, such as his old friend, John Bastwick, were concerned by Lilburne's radicalism. They joined a plot with Denzil Holles against Lilburne. He was arrested and charged with uttering slander against William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons. Lilburne was released without charge on 14th October, 1645.

John Bradshaw now brought Lilburne's case before the Star Chamber. He pointed out that Lilburne was still waiting for most of the pay he should have received while serving in the Parliamentary army. Lilburne was awarded £2,000 in compensation for his sufferings. However, Parliament refused to pay this money and Lilburne was once again arrested. Brought before the House of Lords Lilburne was sentenced to seven years and fined £4,000.

John Lilburne received support from other radicals. In July, 1646, Richard Overton, launched an attack on Parliament: "We are well assured, yet cannot forget, that the cause of our choosing you to be Parliament men, was to deliver us from all kind of Bondage, and to preserve the Commonwealth in Peace and Happiness: For effecting whereof, we possessed you with the same power that was in ourselves, to have done the same; For we might justly have done it ourselves without you, if we had thought it convenient; choosing you (as persons whom we thought qualified, and faithful) for avoiding some inconveniences."

While in Newgate Prison Lilburne used his time studying books on law and writing pamphlets. This included The Free Man's Freedom Vindicated (1647) where he argued that "no man should be punished or persecuted... for preaching or publishing his opinion on religion". He also outlined his political philosophy: "All and every particular and individual man and woman, that ever breathed in the world, are by nature all equal and alike in their power, dignity, authority and majesty, none of them having (by nature) any authority, dominion or magisterial power one over or above another."In another pamphlet, Rash Oaths (1647), he argued: "Every free man of England, poor as well as rich, should have a vote in choosing those that are to make the law."

In 1647 people like John Lilburne and Richard Overton were described as Levellers. In demonstrations they wore sea-green scarves or ribbons. In September, 1647, William Walwyn, the leader of this group in London, organised a petition demanding reform. Their political programme included: voting rights for all adult males, annual elections, complete religious freedom, an end to the censorship of books and newspapers, the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords, trial by jury, an end to taxation of people earning less than £30 a year and a maximum interest rate of 6%.

On this day in 1792 Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights of Women is published. Wollstonecraft's publisher, Joseph Johnson, suggested that she should write a book about the reasons why women should be represented in Parliament. It took her six weeks to write Vindication of the Rights of Women. She told her friend, William Roscoe: "I am dissatisfied with myself for not having done justice to the subject. Do not suspect me of false modesty. I mean to say, that had I allowed myself more time I could have written a better book, in every sense of the word." (35)

In the book Wollstonecraft attacked the educational restrictions that kept women in a state of "ignorance and slavish dependence." She was especially critical of a society that encouraged women to be "docile and attentive to their looks to the exclusion of all else." Wollstonecraft described marriage as "legal prostitution" and added that women "may be convenient slaves, but slavery will have its constant effect, degrading the master and the abject dependent." She added: " I do not wish them (women) to have power over men; but over themselves".

The ideas in Wollstonecraft's book were truly revolutionary and caused tremendous controversy. Horace Walpole described Wollstonecraft as a "hyena in petticoats". Mary Wollstonecraft argued that to obtain social equality society must rid itself of the monarchy as well as the church and military hierarchies. Mary Wollstonecraft's views even shocked fellow radicals. Whereas advocates of parliamentary reform such as Jeremy Bentham and John Cartwright had rejected the idea of female suffrage, Wollstonecraft argued that the rights of man and the rights of women were one and the same thing.

On this day in 1830 Thomas Lawrence died. Lawrence, the son of an innkeeper, was born in Bristol on 13th April 1769. He developed a reputation for painting portraits as a child and by the age of twelve had his own studio in Bath.

In 1787 he became a student at the Royal Academy and two years later, at the age of twenty, he was asked to paint Queen Charlotte, the wife of George III. The king was pleased with the portrait and on the death of Sir Joshua Reynolds in 1792, he appointed Lawrence as the royal painter.

Lawrence was knighted in 1815 and five years later became president of the Royal Academy. Although Lawrence was a very popular painter who could command high fees for his work, he was often heavily in debt. Lawrence painting the portraits of many leading politicians including Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, Sir Francis Burdett and William Wilberforce.

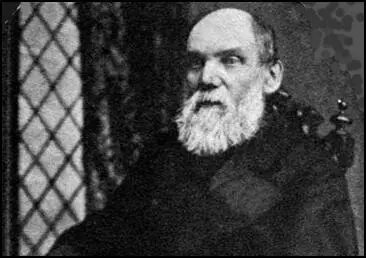

On this day in 1888 Robert Gammage died. Gammage was born into a working class family in Northampton in about 1820. His parents were staunch members of the local Conservative Club. After a brief education Gammage left school at the age of eleven and found work in the Rose and Crown public house. At the age of twelve he became a coach trimmer with a local coach builder. Soon afterwards he became a Radical after reading Common Sense by Tom Paine.

When Henry Hetherington arrived in Northampton to form a branch of the Working Men's Association, Gammage was one of the first people to join. He was further inspired by hearing Henry Vincent make a speech in Northampton. At the age of eighteen, Gammage obtained his first speaking experience at recruitment meetings in villages in the Northampton area.

In February 1840, Gammage decided to leave Northampton. After visiting London, Brighton, Portsmouth, Southampton and Salisbury he found temporary work in Sherbourne. A few weeks later he was on his travels again and over the next few months travelled 1,400 miles in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Wherever he went Gammage made contact with fellow Chartists. Gammage eventually found nine months work in Chelmsford, Essex. However, after nine months he was sacked when his employer discovered he was selling radical newspapers.

Back on the road Gammage met Thomas Cooper in Leicester, George Julian Harney in Sheffield and Fergus O'Connor in Leeds. Gammage gradually developed his public speaking skills and after a spell in Newcastle, he made his living by travelling around the country giving political lectures. An attempt to settle down by becoming a shoemaker came to an end when he was again sacked for his Chartist activities.

In 1852 Gammage joined with Bronterre O'Brien to help establish the National Reform League. In 1852 Gammage was elected to National Executive of the Chartist movement. However, he was a strong opponent of Physical Force and while on the Chartist executive constantly quarreled with Fergus O'Connor and Ernest Jones. Gammage lost the battle and in 1854 was ousted from the National Executive. Gammage had been working on a History of the Chartist Movement for several years. The first edition was published in 1855. Gammage continued to work on the book and a more detailed second edition was published after his death.

After a period working as an insurance agent, Robert Gammage qualified as a doctor in Newcastle. He worked in the Newcastle Infirmary for many years and then opened a medical practice in Sunderland. After his retirement in 1887 he moved back to Northampton where he died on 7th January, 1888, after an accident when he fell off a tram.

On this day in 1896 Arnold Ridley, the only child of William and Rosa Ridley, was born in Bath. The family owned a boot shop. His parents were nonconformists and his mother was a Sunday school teacher.

William Ridley was an outstanding athlete who, in his spare time, taught boxing, fencing and gymnastics. Arnold inherited his father's love of sports, although he claimed he also inherited his mother's total lack of ability to play them.

At Bristol University he developed an interest in acting and in 1913 he appeared in a play called Prunella at the Theatre Royal in Bristol. The following year he left university and found work as a schoolmaster.

On the outbreak of the First World War Ridley attempted to join the British Army but was rejected on medical grounds. At the time the recruiting offices were being inundated with young men and the army could afford to reject people like Ridley who had problems with a toe he had broken playing rugby.

Ridley continued as a schoolteacher in Bristol until volunteering again in 8th December 1915. By this time the army had lost so men as a result of the fighting on the Western Front, they accepted Ridley. He later recalled: "I thought I was doing my duty for my country. I didn't know I was going to be treated like a convict. Did it make better soldiers of the callow youths we were then? I doubt it."

After basic training with the Somerset Light Infantry, Ridley arrived in Arras in March 1916. Ridley had removed his marksman's badge because he did not want to be made a sniper. He later commented: "I didn't go to France to murder people."

Ridley was only on the front-line for two days when he was hit in the back by shrapnel. He was sent to the base hospital at Etaples. After he recovered he rejoined his regiment in the trenches. Soon afterwards he was shot in the thigh and he was sent back to England.

In July 1916, Ridley returned to the Western Front to take part in the Somme Offensive. Ridley went into No Man's Land on 18th August. Fifteen of the men in his group were killed or seriously injured soon after they left the trenches when a preliminary barrage dropped on them instead of the German machine-gun posts. During the attempt to reach Delville Wood, Ridley's battalion suffered nearly 50% casualties. Ridley later pointed out: "It wasn't a question of if I get killed, it was merely a question of when I get killed."

On 15th September 1916, Ridley and his regiment attempted to break the main German defensive line at Flers. For the first time in history the infantry were accompanied by the recently invented tank. "We in the ranks had never heard of tanks. We were told that there was some sort of secret weapon and then we saw this thing go up the right hand corner of Delville Wood. I saw this strange and cumbersome machine emerge from the shattered shrubbery and proceed slowly down the slope towards Flers."

Despite suffering heavy casualties Lance Corporal Ridley and the Somerset Light Infantry were ordered to head for the village of Gueudecourt. "The trenches were full of water and I can remember getting out of the trench and lying on the parapet with the bullets flying around because sleep was such a necessity and death only meant sleep."

Ridley reached a trench that was occupied by the German Army. "I went round one of the traverses, as far as I remember, and somebody hit me on the head with a rifle butt. I was wearing a tin hat, fortunately, but it didn't do me much good. A chap came at me with a bayonet, aiming for a very critical part naturally and I managed to push it down, I got a bayonet wound in the groin. After that I was still very dizzy, from this blow on the head presumably. I remember wrestling with another German and the next thing I saw, it appeared to me that my left hand had gone. After that, I was unconscious."

Other members of the Somerset Light Infantry saved him from certain death. However, the German's bayonet had cut deeply into his left hand, cutting the tendons to his fingers. He was also bleeding badly from the groin wound and a suffered a fractured skull. When he regained consciousness the following morning he recalled: "I always remember my disappointment the next morning when I found that my hand was still on because I thought, well, if I lost my hand I'm all right, I shall live, they can't send me out without a hand again. I was 20 then, it's not altogether a right thought for a young man to hope that he's been maimed for life."

The offensive was a terrible disaster. The Somerset Light Infantry lost 17 officers and 383 other ranks, around two-thirds of the men who took part in the fighting that day. Ridley was eventually rescued by the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers and was taken to a Canadian Hospital close to the front-line where he had the first of seven operations on his hand.

Ridley was sent back to England and spent some time at Woodcote Park Military Hospital before appearing before the British Army Travelling Medical Board. The doctor suggested that the wound to his hand might have been self-inflicted. Ripley replied: "Yes, sir. My battalion is famous for self-inflicted wounds and just to make sure I cracked my skull with a rifle butt as well and ran a bayonet into my groin."

Arnold Ridley was sent to Ireland. He later claimed "I had the feeling that they were trying to kill us off to save our pensions." He was finally discharged from the British Army on 27th August 1917. Ripley later recalled in his unpublished memoirs: "My pension was thirteen (shillings) and nine (pence) a week. But for my father and mother, I don't know what I should have done. I was in considerable pain because there was a nerve injury in my hand."

Later that year he was given a white feather by a woman in the street. He took it without comment. When he was asked why a returning soldier, would be treated in such a way, he answered: "I wasn't wearing my soldier's discharge badge. I didn't want to advertise the fact that I was a wounded soldier and I used to carry it in my pocket."

After the war Ridley found work as a teacher. However, in 1919 he joined the Repertory Theatre in Birmingham. Over the next three years he appeared in over forty productions. Ridley also wrote his own plays, including the highly successful The Ghost Train (1923) and The Wrecker (1924).

Ridley was also involved in writing the scripts or stories for several films including The Wrecker (1929), Third Time Lucky (1930), Keepers of Youth (1931), The Ghost Train (1931), Blind Justice (1934), Seven Sinners (1936) and Royal Eagle (1936).

On the outbreak of the Second World War Ridley joined the British Expeditionary Force. He served as an intelligence officer and was sent to France in 1939. He later admitted that: "Within hours of setting foot on the quay at Cherbourg in September 1939, I was suffering from acute shell shock again. It is quite possible that outwardly I showed little, if any, of it. It took the form of mental suffering that at best could be described as an inverted nightmare." Ridley was evacuated from Dunkirk in May 1940.

Now aged 44, Ridley was demobilised from the army once he arrived back in England. However, he did join the Local Defence Volunteers, an organization that later became the Home Guard. In 1944 he escaped serious injury when his cottage in Caterham was hit by a VI Flying Bomb.

After the war Ridley he appeared on the stage, radio and television. This included the part of Doughy Hood in The Archers. Her also featured in Crossroads and Coronation Street. However, his most famous role was as Charles Godfrey in Dad's Army (1968-1977). Arnold Ridley, who received an OBE in 1982, died in Northwood on 12th March 1984.

On this day in 1912 Sophia Jex-Blake died. Sophia, the daughter of Thomas Jex-Blake and Mary Cubitt, was born at 3 Croft Place, Hastings on 21st January, 1840. Thomas Jex-Blake was a successful barrister, but he had retired at the time of her birth.

In 1851 the family moved to 13 Sussex Square, Brighton. Sophia attended several private boarding-schools as a child. Sophia's parents were Evangelical Anglicans who held very traditional views on education and at first refused permission for her to study at college.

Eventually Dr. Jex-Blake gave his permission and in 1858 Sophia began attending classes at Queen's College in Harley Street. Two of her fellow students were Dorothea Beale and Frances Mary Buss. One of her teachers was the Reverand John Maurice, one of the founders of the Christian Socialist movement. He told her: "The vocation of a teacher is an awful one… she will do others unspeakable harm if she is not aware of its usefulness… How can you give a woman self-respect, how can you win for her the respect of others… Watch closely the first utterances of infancy, the first dawnings of intelligence; how thoughts spring into acts, how acts pass into habits. The study is not worth much if it is not busy about the roots of things."

Sophia did so well that she was asked to become a tutor of mathematics at the college. Sophia's parents believed it was wrong for middle-class women to work and only gave their approval after she agreed not to accept a salary. During this period she shared a house in Nottingham Place with Octavia Hill and her family.

While in London became friends with a group of feminists that included Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett, Adelaide Anne Procter, and Emily Faithfull. According to Louisa Garrett Anderson: "They were comrades and worked for a great end." Eventually, most of these women became involved in the struggle for women's suffrage.

In 1862 Jex-Blake spent several months in Edinburgh being taught by private tutors. She also helped Elizabeth Garrett to prepare her application to University of Edinburgh for enrolment as a medical student. The two had previously met in London, but during Elizabeth's visit to Edinburgh, Jex-Blake learned more about the problems facing women who wished to practise medicine.After Queen's College, Sophia spent time teaching in Germany and the United States. When she returned she wrote a book about his experiences A Visit to Some American Schools and Colleges (1867). Sophia had been especially impressed with the experiments in the United States with co-education. While in America she met Dr. Lucy Sewell, the resident physician at the New England Hospital for Women. Sophia now decided she would rather be a doctor rather than a teacher.

Sophia Jex-Blake wrote a pamphlet, Medicine as a Profession for Women (1869), where she argued the case for women doctors: "One argument usually advanced against the practice of medicine by women is that there is no demand for it; that women, as a rule, have little confidence in their own sex, and had rather be attended by a man… it is probably a fact, that until lately there has been no demand for women doctors, because it does not occur to most people to demand what does not exist; but that very many women have wished that they could be medically attended by those of their own sex I am very sure, and I know of more than one case where ladies have habitually gone through one confinement after another without proper attendance, because the idea of employing a man was so extremely repugnant to them."

Sophia Jex-Blake began to explore the possibility of training as a doctor. This was a problem as British medical schools refused to accept women students. She eventually persuaded University of Edinburgh to allow her and her friend, Edith Pechy, to attend medical lectures. This annoyed the male students and attempts were made to stop them receiving teaching and taking their examinations. As Jex-Blake later pointed out: "On the afternoon of Friday 18th November 1870, we walked to the Surgeon's Hall, where the anatomy examination was to be held. As soon as we reached the Surgeon's Hall we saw a dense mob filling up the road… The crowd was sufficient to stop all the traffic for an hour. We walked up to the gates, which remained open until we came within a yard of them, when they were slammed in our faces by a number of young men." Shirley Roberts adds: "Then a sympathetic student emerged from the hall; he opened the gate and ushered the women inside. They took their examination and all passed." Although Jex-Blake and Pechy both passed their examinations, university regulations only allowed medical degrees to be given to men. The British Medical Association therefore refused to register the women as doctors.

Sophia Jex-Blake's case generated a great deal of publicity and Russell Gurney, a M.P. who supported women's rights, decided to try and change the law. In 1876 Gurney managed to persuade Parliament to pass a bill that empowered all medical training bodies to educate and graduate women on the same terms as men. The first educational institution to offer this opportunity to women was the Irish College of Physicians. Sophia took up their offer and qualified as a doctor in 1877.

In June 1878, Jex-Blake opened a medical practice at 4 Manor Place; three months later she established a dispensary (an out-patient clinic) for impoverished women at 73 Grove Street, Fountainbridge. These ventures were highly successful but after the death of one of her assistants, she suffered from depression. She closed her practice and left the dispensary in the care of her medical colleagues.

Sophia Jex-Blake remained inactive for several years but eventually decided to join forces with Elizabeth Garrett Anderson in her efforts to establish a Medical School for women. In 1887 they opened the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. In its second year the school was disrupted by disputes between Jex-Blake and several of the students who resented her imposition of strict rules of conduct.

One of her close friends, Dr Margaret Todd, the author of The Life of Sophia Jex-Blake (1918), once said: "She was impulsive, she made mistakes and would do so to the end of her life: her naturally hasty temper and imperious disposition had been chastened indeed, but the chastening fire had been far too fierce to produce perfection … But there was another side to the picture after all. Many of those who regretted and criticised details were yet forced to bow before the big transparent honesty, the fine unflinching consistency of her life." While in Edinburgh, Sophia played an active role in the local Women's Suffrage Society.

When Dr. Jex-Blake, dismissed two students for what Elsie Inglis considered to be a trivial offence, she obtained funds from her father and some of his wealthy friends, and established a rival medical school, the Scottish Association for the Medical Education for Women.

In 1899 Sophia Jex-Blake retired to Windydene, a small farm at Mark Cross, some 5 miles south of Tunbridge Wells. Sophia Jex-Blake continued to campaign for women's suffrage until her death at Windydene on 7th January 1912.

On this day in 1934 Weekly Fascist News described the growth in membership the British Union of Fascists in Worthing as "phenomenal". At an election meeting in Broadwater on 16th October 1933, Charles Bentinck Budd revealed he had recently met Sir Oswald Mosley and had been convinced by his political arguments and was now a member of the British Union of Fascists (BUF). Budd added that if he was elected to the local council "you will probably see me walking about in a black shirt".

Budd won the contest and the national press reported that Worthing was the first town in the country to elect a Fascist councillor. Worthing was now described as the "Munich of the South". A few days later Mosley announced that Budd was the BUF Administration Officer for Sussex. Budd also caused uproar by wearing his black shirt to council meetings.

On Friday 1st December 1933, the BUF held its first public meeting in Worthing in the Old Town Hall. According to one source: "It was crowded to capacity, with the several rows of seats normally reserved for municipal dignitaries and magistrates now occupied by forbidding, youthful men arrived in black Fascist uniforms, in company with several equally young women dressed in black blouses and grey skirts."

Budd reported that over 150 people in Worthing had joined the British Union of Fascists. Some of the new members were former communists but the greatest intake had come from increasingly disaffected Conservatives. The Weekly Fascist News described the growth in membership as "phenomenal" as a few months ago members could be counted on one's fingers, and now "hundreds of young men and women -.together with the many leading citizens of the town - now participated in its activities".

The mayor of Worthing, Harry Duffield, the leader of the Conservative Party in the town, was most favourably impressed with the Blackshirts and congratulated them on the disciplined way they had marched through the streets of Worthing. He reported that employers in the town had written to him giving their support for the British Union of Fascists. They had "no objection to their employees wearing the black shirt even at work; and such public spirited action on their part was much appreciated."

Charles Bentinck Budd gave an interview to the Worthing Journal, in November, 1933. "Fascism is the one thing that will save this country from the trouble for which it is heading! When I was put in charge of this area I was given to understand that I would find things slow in West Sussex; but now I find that people very eager and interested in our movement."

Budd established branches of the BUF in Chichester, Bognor, Littlehampton, Burgess Hill, Rustington, Horsham, Petworth and Selsey. One of its most active members was John Sidney Crosland, the son of James Louis Crosland, the Vicar of Rustington, who also attended meetings. Crosland sold copies of the Blackshirt from the corner of Beach Road in Littlehampton and by early 1934 was selling 110 copies a week. Another active member was Jorian Jenks, a farmer from Angmering.

It was arranged for Sir Oswald Mosley and William Joyce to address a meeting at the Worthing Pavilion Theatre on 9th October, 1934. The British Union of Fascists covered the town with posters with the words "Mosley Speaks", but during the night someone had altered the posters to read "Gasbag Mosley Speaks Tripe". It was later discovered that this had been done by Roy Nicholls, the chairman of the Young Socialists.

The venue was packed with fascist supporters from Sussex. Surprisingly they were willing to pay between 1s.6d and 7s. for their tickets. According to Michael Payne: "Finally the curtain rose to reveal Sir Oswald himself standing alone on the stage. Clad entirely in black, the great silver belt buckle gleaming, the right arm raised in the Fascist salute, he was spell-bindingly illuminated in the hushed, almost reverential atmosphere by the glare of spotlights from right, left and centre. A forest of black-sleeved arms immediately shot up to hail him."

The meeting was disrupted when a few hecklers were ejected by hefty East End bouncers. Mosley, however, continued his speech undaunted, telling his audience that Britain's enemies would have to be deported: "We were assaulted by the vilest mob you ever saw in the streets of London - little East End Jews, straight from Poland. Are you really going to blame us for throwing them out?"

At the close of proceedings Mosley and Joyce, accompanied by a large body of blackshirts, marched along the Esplanade.They were protected by all nineteen available members of the Borough's police force. The crowd of protesters, estimated as around 2,000 people, attempted to block their path. A ninety-six-year-old woman, Doreen Hodgkins, was struck on the head by a Blackshirt before being escorted away. When the Blackshirts retreated inside, the crowd began to chant: "Poor old Mosley's got the wind up!"

The Fascists went into Montague Street in an attempt to get to their headquarters in Anne Street. The author of Storm Tide: Worthing 1933-1939 (2008) has pointed out: "Sir Oswald, clearly out of countenance and feeling menaced, at once ordered his tough, battle-hardened bodyguards - all of imposing physique and, like their leader, towering over the policemen on duty - to close ranks and adopt their fighting stance which, unsurprisingly, as all were trained boxers, had been modelled on, and closely resembled, that of a prize fighter."

Superintendent Clement Bristow later claimed that a crowd of about 400 people attempted to stop the Blackshirts from getting to their headquarters. Francis Skilton, a solicitor's clerk who had left his home at 30 Normandy Road to post a letter at the Central Post Office in Chapel Road, and got caught up in the fighting. A witness, John Birts, later told the police that Skilton had been "savagely attacked by at least three Blackshirts."

According to The Evening Argus: "The fascists fought their way to Mitchell's Cafe and barricaded themselves inside as opponents smashed windows and threw tomatoes. As midnight loomed, they broke out and marched along South Street to Warwick Street. One woman bystander was punched in the face in what witnesses described as 'guerrilla warfare'. There were casualties on both sides as a 'seething, struggling mass of howling people' became engaged in running battles. People in nightclothes watched in amazement from bedroom windows overlooking the scene."

The next day the police arrested Charles Budd, Oswald Mosley, William Joyce and Bernard Mullans and accused them of "with others unknown they did riotously assemble together against the peace". The court case took place on 14th November 1934. Charles Budd claimed that he telephoned the police three times on the day of the rally to warn them that he believed "trouble" had been planned for the event. A member of the Anti-Fascist New World Fellowship had told him that "we'll get you tonight". Budd had pleaded for police protection but only four men had turned up that night. He argued that there had been a conspiracy against the BUF that involved both the police and the Town Council.

Several witnesses gave evidence in favour of the BUF members. Eric Redwood - a barrister from Chiddingfield, that the trouble was caused by a gang of "trouble-seeking roughs" and that Budd, Mosley, Joyce and Mullans "acted with admirable restraint". Herbert Tuffnell, a retired District Commissioner of Uganda, also claimed that it was the anti-fascists who started the fighting.

Joyce, in evidence, said that "any suggestion that they came down to Worthing to beat up the crowd was ridiculous in the highest degree. They were menaced and insulted by people in the crowd." Mullans claimed that told an anti-fascist demonstrator that he "should be ashamed for using insulting language in the presence of women". The man then hit in the eye and he retaliated by punching the man in the mouth.

John Flowers, the prosecuting council told the jury that "if you come to the conclusion that there was an organised opposition by roughs and communists and others against the Fascists... that this brought about the violence and that the defendants and their followers were protecting themselves against violence, it will not be my duty to ask you to find them guilty." The jury agreed and all the men were found not guilty.

The monthly Worthing Journal was more hostile to Budd and the British Union of Fascists than most of the town's newspapers. In March 1935, it reported with pleasure the resignation of Superintendent Clement Bristow. It was seen by many as a consequence of his apparent sympathy for the fascist cause, for in court he had described fascists in the town as "very nice Worthing people". (38) A few months later it reported: "Fascism has come to Worthing, but Worthing has shown through its accredited representatives that it is not yet ready to submit to a Dictatorship."

Charles Bentinck Budd continued to get support for the British Union of Fascists in the town. Lionel J. Redgrave Cripps, the Worthing architect, and his wife, spent three months in Nazi Germany in the summer of 1935. He commented that they were "simply amazed at the wonderful progress that has been made since we were last there five years ago." Cripps argued that "despondency and despair had been replaced by optimism, efficiency, unity, amazing energy and bursting vitality; the whole nation seemingly inspired with a new and great ideal in which all classes seemed genuinely to believe with the intensity of a religious fervour."

Redgrave Cripps, was especially impressed with Hitler's Strength Through Joy programme. It was established as a subsidiary of the German Labour Front (DAF) on 27th November, 1933. It was an attempt to organize workers' leisure time rather than allow them to organize it for themselves, and therefore enable leisure to serve the interests of the government. Robert Ley, the leader of DAF, claimed that "workers were to gain strength for their work by experiencing joy in their leisure".

In a letter to the Worthing Herald, Redgrave Cripps, argued: "The essentially constructive work done by Hitler in Germany during the very short period he has been in power is little short of miraculous. There is for instance, more practical Socialism for the actual workers and actually accomplished in Hitler's Strength Through Joy movement than anything that our English Labour Party has ever even dreamt of, let alone done. Also Hitler's wonderful new motorways are years ahead of our efforts in this direction. I only wish all my fellow countrymen in England could come here and see these wonderful constructive works for themselves... Germany today is a nation of young realists who believe in action rather than talk."

R. G. Martin, the headmaster of Worthing High School for Boys, had originally been critical of the Budd's attempts to form a branch of the BUF in the town. At the annual dinner of the Old Azurian's Association, he said that he did not expect former pupils to join as they had "cold common sense among those who had the best education the town could offer." However, in August 1935, he controversially took a school party to Nazi Germany with their production of Shakespeare's Twelfth Night . On their return, Max Fuller, the head of WHSB's Dramatic Society, reported that in Germany "Hitler is looked upon as the saviour of the country."

The following year Martin invited 17 members of the Hitler Youth to visit Worthing High School for Boys. They arrived in April 1936. (44) Martin commented that the German boys were a "sturdy lot and are far more burly than their English counterparts". That afternoon they put on a display of gymnastics that Martin described as "stunning". Although he added their imposing physiques they lacked, the suppleness of his boys.

The local historian, Freddie Feest, argues: "It has since been well documented that there were ulterior motives for most such visits and that German youth with strong Nazi-influenced motivation were surreptitiously – though with various degrees of success and reliability – collecting information, documents and photographs during their tours that might prove invaluable when the time came for Nazi forces to carry out an invasion of that country." Feest suspects that the visit was arranged because members of staff were sympathetic to fascism: "So, had R. G. Martin been duped by the Nazi propaganda machine into believing such a visit was merely culturally inspired? Possibly. Certainly, according to several former pupils, their headmaster and at least one other teacher involved with the trip to Germany were greatly impressed by and demonstrably sympathetic to many of the Nazi ideals projected during the two-way visits."

Charles Bentinck Budd was not a successful Administration Officer for the British Union of Fascists in Sussex. He argued with most of the senior officers in the organisation. One report suggested "Budd's amazing unpopularity in that town (Worthing), more members have left the Movement than are currently in the Branch." On 27th November 1935, having divorced his wife, Budd resigned his position in Sussex and moved to Birmingham. On 22nd June 1936, he was appointed BUF Inspecting Officer for the Midlands Area. A few months later he became the BUF Prospective Parliamentary candidate for Ladywood, Birmingham. (47)

Worthing Journal kept up its attack on the BUP in the town. This included the policies of Adolf Hitler in Nazi Germany. It claimed that the whole nation was in thrall to the "swastika... without which the Nazis seem unable to march, salute or shout." (48) One unnamed fascist sent in a threatening letter: "Kindly refrain in future from writing your filthy remarks and opinions in the Worthing Journal. It is quite time for such feeble minded scrawling to cease. The first step towards improving Worthing would be the extermination of people like you."

Oswald Mosley returned to Worthing in November 1938. He claimed that he had received just as much persecution in England as the Jews had in Germany. Worthing Journal responded: "Mosley tried to make us believe that the treatment which he received in Liverpool, London and evening Worthing was as bad. If this is the case, Mosley is indeed a brave man. I did not realise that he had been chased down streets by howling mobs of lunatics, beating him and scrounging him as he went; that he had been spat on, trampled on, had all his property confiscated and then been sent to a concentration camp."

In the spring of 1938 Budd visited Worthing and at the BUF's offices he met Enid Gertrude Baker, a prominent, zealous Fascist who lived at St Elmo in Goring Road. Within a few weeks she became his mistress. In public he referred to her as his secretary. (51) In July she visited Nazi Germany and wrote back to Budd that: "I am having a very interesting holiday and Deutchsland is a great country - the SS uniforms are just like ours." Later that holiday she wrote that during a big parade Adolf Hitler "passed me twice" and she also saw Joseph Goebbels in his car.

Charles Bentinck Budd fell out with Mosley over the role of women, who he believed should have the same rights as men within the movement. In 1939 he resigned from the British Union of Fascists and applied to join his old regiment. Just before the outbreak of the Second World War he was appointed Adjutant of the 44th Counties Division of the Royal Engineers, at its office in Brighton. Budd claimed that he left the BUF on the outbreak of the Second World War.