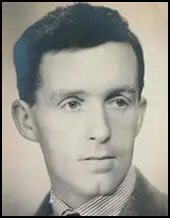

Arnold Ridley

Arnold Ridley, the only child of William and Rosa Ridley, was born in Bath on 7th January 1896. The family owned a boot shop. His parents were nonconformists and his mother was a Sunday school teacher.

William Ridley was an outstanding athlete who, in his spare time, taught boxing, fencing and gymnastics. Arnold inherited his father's love of sports, although he claimed he also inherited his mother's total lack of ability to play them.

At Bristol University he developed an interest in acting and in 1913 he appeared in a play called Prunella at the Theatre Royal in Bristol. The following year he left university and found work as a schoolmaster.

On the outbreak of the First World War Ridley attempted to join the British Army but was rejected on medical grounds. At the time the recruiting offices were being inundated with young men and the army could afford to reject people like Ridley who had problems with a toe he had broken playing rugby.

Ridley continued as a schoolteacher in Bristol until volunteering again in 8th December 1915. By this time the army had lost so men as a result of the fighting on the Western Front, they accepted Ridley. He later recalled: "I thought I was doing my duty for my country. I didn't know I was going to be treated like a convict. Did it make better soldiers of the callow youths we were then? I doubt it."

After basic training with the Somerset Light Infantry, Ridley arrived in Arras in March 1916. Ridley had removed his marksman's badge because he did not want to be made a sniper. He later commented: "I didn't go to France to murder people."

Ridley was only on the front-line for two days when he was hit in the back by shrapnel. He was sent to the base hospital at Etaples. After he recovered he rejoined his regiment in the trenches. Soon afterwards he was shot in the thigh and he was sent back to England.

In July 1916, Ridley returned to the Western Front to take part in the Somme Offensive. Ridley went into No Man's Land on 18th August. Fifteen of the men in his group were killed or seriously injured soon after they left the trenches when a preliminary barrage dropped on them instead of the German machine-gun posts. During the attempt to reach Delville Wood, Ridley's battalion suffered nearly 50% casualties. Ridley later pointed out: "It wasn't a question of if I get killed, it was merely a question of when I get killed."

On 15th September 1916, Ridley and his regiment attempted to break the main German defensive line at Flers. For the first time in history the infantry were accompanied by the recently invented tank. "We in the ranks had never heard of tanks. We were told that there was some sort of secret weapon and then we saw this thing go up the right hand corner of Delville Wood. I saw this strange and cumbersome machine emerge from the shattered shrubbery and proceed slowly down the slope towards Flers."

Despite suffering heavy casualties Lance Corporal Ridley and the Somerset Light Infantry were ordered to head for the village of Gueudecourt. "The trenches were full of water and I can remember getting out of the trench and lying on the parapet with the bullets flying around because sleep was such a necessity and death only meant sleep."

Ridley reached a trench that was occupied by the German Army. "I went round one of the traverses, as far as I remember, and somebody hit me on the head with a rifle butt. I was wearing a tin hat, fortunately, but it didn't do me much good. A chap came at me with a bayonet, aiming for a very critical part naturally and I managed to push it down, I got a bayonet wound in the groin. After that I was still very dizzy, from this blow on the head presumably. I remember wrestling with another German and the next thing I saw, it appeared to me that my left hand had gone. After that, I was unconscious."

Other members of the Somerset Light Infantry saved him from certain death. However, the German's bayonet had cut deeply into his left hand, cutting the tendons to his fingers. He was also bleeding badly from the groin wound and a suffered a fractured skull. When he regained consciousness the following morning he recalled: "I always remember my disappointment the next morning when I found that my hand was still on because I thought, well, if I lost my hand I'm all right, I shall live, they can't send me out without a hand again. I was 20 then, it's not altogether a right thought for a young man to hope that he's been maimed for life."

The offensive was a terrible disaster. The Somerset Light Infantry lost 17 officers and 383 other ranks, around two-thirds of the men who took part in the fighting that day. Ridley was eventually rescued by the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers and was taken to a Canadian Hospital close to the front-line where he had the first of seven operations on his hand.

Ridley was sent back to England and spent some time at Woodcote Park Military Hospital before appearing before the British Army Travelling Medical Board. The doctor suggested that the wound to his hand might have been self-inflicted. Ripley replied: "Yes, sir. My battalion is famous for self-inflicted wounds and just to make sure I cracked my skull with a rifle butt as well and ran a bayonet into my groin."

Ridley was sent to Ireland. He later claimed "I had the feeling that they were trying to kill us off to save our pensions." He was finally discharged from the British Army on 27th August 1917. Ripley later recalled in his unpublished memoirs: "My pension was thirteen (shillings) and nine (pence) a week. But for my father and mother, I don't know what I should have done. I was in considerable pain because there was a nerve injury in my hand."

Later that year he was given a white feather by a woman in the street. He took it without comment. When he was asked why a returning soldier, would be treated in such a way, he answered: "I wasn't wearing my soldier's discharge badge. I didn't want to advertise the fact that I was a wounded soldier and I used to carry it in my pocket."

After the war Ridley found work as a teacher. However, in 1919 he joined the Repertory Theatre in Birmingham. Over the next three years he appeared in over forty productions. Ridley also wrote his own plays, including the highly successful The Ghost Train (1923) and The Wrecker (1924).

Ridley was also involved in writing the scripts or stories for several films including The Wrecker (1929), Third Time Lucky (1930), Keepers of Youth (1931), The Ghost Train (1931), Blind Justice (1934), Seven Sinners (1936) and Royal Eagle (1936).

On the outbreak of the Second World War Ridley joined the British Expeditionary Force. He served as an intelligence officer and was sent to France in 1939. He later admitted that: "Within hours of setting foot on the quay at Cherbourg in September 1939, I was suffering from acute shell shock again. It is quite possible that outwardly I showed little, if any, of it. It took the form of mental suffering that at best could be described as an inverted nightmare." Ridley was evacuated from Dunkirk in May 1940.

Now aged 44, Ridley was demobilised from the army once he arrived back in England. However, he did join the Local Defence Volunteers, an organization that later became the Home Guard. In 1944 he escaped serious injury when his cottage in Caterham was hit by a VI Flying Bomb.

After the war Ridley he appeared on the stage, radio and television. This included the part of Doughy Hood in The Archers. Her also featured in Crossroads and Coronation Street. However, his most famous role was as Charles Godfrey in Dad's Army (1968-1977).

Arnold Ridley, who received an OBE in 1982, died in Northwood on 12th March 1984.

Primary Sources

(1) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

As it went, it wasn't a question of "if I get killed", it was merely a question of "when I get killed", because a battalion went over 800 strong, you lost 300 or 400, half the number, perhaps more. Now it wasn't a question of saying, "I am one of the survivors, hurrah, hurrah", because you didn't go home.... Out came another draft of 400 and you went over the top again.

There was an awful feeling of a great black cloud on top of one the whole time, there seemed to be no future...! think one lost one's sensitivity. You lived like a worm and your horizon was very limited to "shall I get back in time for the parcel to come? Shall I ever get back to eat that cake that I know mother has sent me?" You certainly lived one day at a time. I didn't dare think of tomorrow It was general abject misery. I think your imagination became dulled. I think in the end you just became a thing.

(2) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

We in the ranks had never heard of tanks. We were told that there was some sort of secret weapon and then we saw this thing go up the right hand corner of Delville Wood. I saw this strange and cumbersome machine emerge from the shattered shrubbery and proceed slowly down the slope towards Flers.

(3) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

If you've ever tried to keep awake when you haven't had any sleep for days, it's not a question of allowing yourself to go to sleep. I can remember lying in a sunken road behind Gueudecourt. The trenches were full of water and I can remember getting out of the trench and lying on the parapet with the bullets flying around because sleep was such a necessity and death only meant sleep.

(4) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

I knew one man who was very badly treated as a Conscientious Objector because he wouldn't submit to a medical examination. Had he submitted, he would have been grade 99 and they would never have had him. He was half-blind and weedy but he just wouldn't on principle.

(5) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

We were told that there was a pocket of resistance left over and that two advances had left this pocket and we were told that we would attack. We would get a five minute barrage, which we got, but Jerry and the German machine guns were firing, saying "we know you are coming over, come on, where are you?" Although the plans had gone wrong, the whistles blew and we went over the top just the same. At that time I was a bomber and we got down to the first trench...

I went round one of the traverses, as far as I remember, and somebody hit me on the head with a rifle butt. I was wearing a tin hat, fortunately, but it didn't do me much good. A chap came at me with a bayonet, aiming for a very critical part naturally and I managed to push it down, I got a bayonet wound in the groin. After that I was still very dizzy, from this blow on the head presumably. I remember wrestling with another German and the next thing I saw, it appeared to me that my left hand had gone. After that, I was unconscious...

I always remember my disappointment the next morning when I found that my hand was still on because I thought, well, if I lost my hand I'm all right, I shall live, they can't send me out without a hand again. I was 20 then, it's not altogether a right thought for a young man to hope that he's been maimed for life.

(6) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

I returned to my depot for what had been termed final adjustment of discharge. All had seemed set fair when I was ordered to appear before a TMB (Travelling Medical Board) and after being kept stark naked for over an hour in a very well ventilated stone corridor on a bitter January morning I found myself in the presence of an excessively corpulent surgeon general. "Well, what's the matter with you?" he demanded, anxious to get the matter settled with all speed. I held out my shattered left hand which was the most obvious of my injuries. He took it and twisted it in an agonising grip. "How did you get this?" he demanded. "Jack knife?" Probably this was only meant as a heavy joke but I was still suffering from shell shock, blue with cold and in considerable pain. "Yes, sir," I replied. "My battalion is famous for self-inflicted wounds and just to make sure I cracked my skull with a rifle butt as well and ran a bayonet into my groin."

The General's normally ruddy countenance changed to a deep shade of purple. He gave my hand a twist in the opposite direction. "Treatment at Command Depot," he barked, so instead of returning to civilian life, I was granted a further experience of military matters at No 2 Command Depot, County Cork.

(7) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

My pension was thirteen (shillings) and nine (pence) a week. But for my father and mother, I don't know what I should have done. I was in considerable pain because there was a nerve injury in my hand. I was in very bad physical health, I had lost weight terribly and I had been sent out to a command depot in Ireland where I had been for the winter. I had the feeling that they were trying to kill us off to save our pensions.

(8) Arnold Ridley, The Train and Other Ghosts (1970c)

All my old friends were either dead or still in the services and I refused to make new ones, preferring to wander alone through the street and gardens of Bath in a state of Stygian gloom. Quite suddenly, self-preservation came to my rescue. I realised that unless I made a supreme effort to pull myself together, I stood a fair chance of being put quietly away in some convenient mental hospital. I had to do something about it and quickly too.

(9) The Bath Chronicle (April 1919)

Mr Arnold Ridley, the only son of Mr and Mrs W R Ridley, of Manvers Street, Bath, we are pleased to hear is making gratifying progress in the histrionic art. This clever young actor's success is all the more pleasing as he suffers a considerable handicap by a wound received in the Somme fighting of 1916. As a lance corporal in the 6th Somersets he had a deadly hand-to-hand encounter with a German near Delville Wood, and the Hun bayonet pierced his left hand cutting a sinew, with the consequence that Mr Ridley's forearm is practically useless. But this defect he artistically camouflages in his stage make-up.

(10) Richard Van Emden & Victor Piuk, Famous 1914-1918 (2008)

There has been some confusion over the years as to whether Arnold Ridley won the Military Medal or not. In an episode of Dad's Army, a picture of Charles Godfrey wearing the MM is seen, but the actor himself never received one. He was, according to conversations between Arnold and his son Nicolas, recommended for the Distinguished Conduct Medal.

"A horrible irony is that my father was not the sort of man who was out for official recognition, yet all he had ever wanted was the Military Medal. He told me that when he came back from No Man's Land after an attack on the Somme, he was standing around with four or five other boys when an officer spoke to them. He said he was going to put them all up for the MM except for my father who, because he had a lance corporal stripe on, he would put up for the Distinguished Conduct Medal. All the other men got their MMs but he didn't get the DCM, and that did embitter him a little bit. It is exactly the sort of thing he would not have normally cared about, but I think he felt it was a badge of comradeship. When he was awarded an OBE for playing a small comedy part in a television series, I felt it was a poor reward for someone who had served in two world wars."