On this day on 6th July

On this day in 1535 Thomas More was taken to Tower Hill. More told his executioner: "You will give me this day a greater benefit than ever any mortal man can be able to give me. Pluck up thy spirits, man, and be not afraid to do thine office. My neck is very short; take heed, therefore, thou strike not awry for saving of thine honesty."

More's family were given the headless corpse to the family and it was buried at the church of St Peter ad Vincula in the Tower of London. Thomas More's head was boiled, as usual, to preserve it and to add terror to its appearance before exhibiting it. It was put on the pole on London Bridge which Fisher's head had occupied for the past fortnight. After a few days, Margaret Roper, his daughter, bribed a constable of the watch to take it down and give it to her. She hid the head in some place where no one found it.

In December 1533 Henry VIII gave Thomas Cromwell permission to unleash all the resources of the state in discrediting the papacy. "In one of the fiercest and ugliest smear campaigns in English history the minister showed his mastery of propaganda techniques as the pope was attacked throughout the nation in sermons and pamphlets. In the new year another session of parliament was summoned to enact the necessary legislation to break formally the remaining ties which bound England to Rome, again under Cromwell's meticulous supervision."

In March 1534 Pope Clement VII eventually made his decision. He announced that Henry's marriage to Anne Boleyn was invalid. Henry reacted by declaring that the Pope no longer had authority in England. In November 1534, Parliament passed the Act of Supremacy. This gave Henry the title of the "Supreme head of the Church of England". A Treason Act was also passed that made it an offence to attempt by any means, including writing and speaking, to accuse the King and his heirs of heresy or tyranny. All subjects were ordered to take an oath accepting this.

Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused to take the oath and were imprisoned in the Tower of London. More was summoned before Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Thomas Cromwell at Lambeth Palace. More was happy to swear that the children of Anne Boleyn could succeed to the throne, but he could not declare on oath that all the previous Acts of Parliament had been valid. He could not deny the authority of the pope "without the jeopardizing of my soul to perpetual damnation."

Elizabeth Barton was arrested and executed for prophesying the King's death within a month if he married Anne Boleyn. Henry's daughter, Mary I, also refused to take the oath as it would mean renouncing her mother, Catherine of Aragon. On hearing this news, Anne Boleyn apparently said that the "cursed bastard" should be given "a good banging". Mary was only confined to her room and it was her servants who were sent to prison.

On 15th June, 1534, it was reported to Thomas Cromwell that the Observant Friars of Richmond refused to take the oath. Two days later two carts full of friars were hanged, drawn and quartered for denying the royal supremacy. A few days later a group of Carthusian monks were executed for the same offence. "They were chained upright to stakes and left to die, without food or water, wallowing in their own filth - a slow, ghastly death that left Londoners appalled". (80) Cromwell told More that the example he was setting was resulting in other men being executed. More responded: "I do nobody harm. I say none harm, I think none harm, but wish everybody good. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I long not to live."

In April 1535 the priors of the Carthusian houses, in Charterhouse Priory in London, Axholme Priory in North Lincolnshire and Beauvale Priory in Nottinghamshire, refused to acknowledge the King to be the Head of the Church of England. They were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn on 4th May.

In May 1535, Pope Paul III created Bishop John Fisher a Cardinal. This infuriated Henry VIII and he ordered him to be executed on 22nd June at the age of seventy-six. A shocked public blamed Queen Anne for his death, and it was partly for this reason that news of the stillbirth of her child was suppressed as people might have seen this as a sign of God's will. Anne herself suffered pangs of conscience on the day of Fisher's execution and attended a mass for the "repose of his soul".

Henry VIII decided it was time that Thomas More was tried for treason. The trial was held in Westminster Hall and began on 1st July. Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley presided over the case. Unlike Bishop Fisher, More denied that he had ever said that the king was not Head of the Church, but claimed that he had always refused to answer the question, and that silence could never constitute an act of high treason. The prosecution argued that silence implied consent. As Jasper Ridley, the author of The Statesman and the Fanatic (1982) has pointed out, "while Fisher and the Carthusians, when facing their judges, took their stand for the Papal Supremacy, More rested his defence on a legal quibble".

It was difficult for the prosecution to maintain that anything that More had said or done constituted a malicious denial of the king's title as Supreme Head. Sir Richard Rich, the Solicitor-General, gave evidence that caused Thomas More considerable problems. Rich recalled a conversation that he had with More on 12th June, 1532, when he visited him in the Tower of London. According to P. R. N. Carter: "The two lawyers engaged in a hypothetical discussion of the power of parliament to make the king supreme head of the church.... and Rich testified (falsely) that during their conversation the former lord chancellor had explicitly denied the supremacy. The alternative view is that More relaxed somewhat during the interrogation by Rich in what was a bit of professional jousting, but that Rich did not see or report this as something new. However, someone, possibly Cromwell, saw that More's statements could be used to convict him of denying the royal supremacy. Hence Rich's evidence was not dishonest, merely used in a way he never foresaw."

The verdict was never in doubt and Thomas More was convicted of treason. Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley "passed sentence of death - the full sentence required by law, that More was to be hanged, cut down while still living, castrated, his entrails cut out and burned before his eyes, and then beheaded. As he was being taken back to the Tower, Margaret Roper and his son John broke through the cordon of guards to embrace him. After he had bidden them farewell, as he moved away, Margaret ran back, again broke through the cordon, and embraced him again."

Henry VIII commuted the sentence to death by the headsman's axe. On the night before his execution, Thomas More sent Margaret Roper his hairshirt, so that no one should see it on the scaffold and so that she could treasure that link that was a secret between the two of them. He wrote to her saying: "I long to go to God... I never liked your manner toward me better than when you kissed me last; for I love when daughterly love, and dear charity, hath no leisure to look to worldly courtesy. Farewell, my dear child, and pray for me, and I shall for you and all your friends, that we may merrily meet in Heaven."

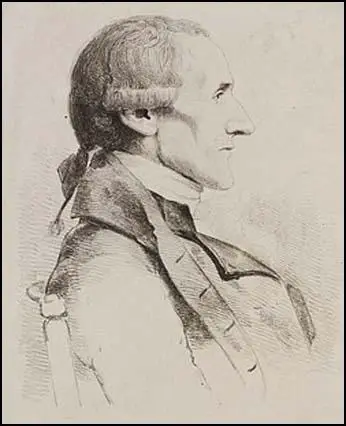

On this day in 1813 Granville Sharp died and was buried in Fulham churchyard seven days later.

Granville Sharp, the ninth and youngest son of Thomas Sharp (1693–1758) and his wife, Judith Wheler,was born in Durham on 10th November 1735. The son of the archdeacon of Northumberland, and the grandson of John Sharp, the Archbishop of York, he decided against a career in the Church of England and instead served an apprenticeship in May 1750 to a Quaker linen draper in London.

According to his biographer, Grayson Ditchfield: "These contacts encouraged Sharp to engage in theological disputation, and he used his leisure to acquire that largely self-taught knowledge of Greek and Hebrew which formed an important basis for his career as a writer."

In 1757 he completed his apprenticeship and became a freeman of the City of London as a member of the Fishmongers' Company. The following year he obtained a post as a clerk in the Ordnance Office at the Tower of London. In 1764 he received promotion to the minuting branch as a clerk-in-ordinary.

In 1765 Sharp was living with his brother, a surgeon in Wapping. One day Jonathan Strong, a black man, arrived at the house. Strong was a slave who had been so badly beaten by his master, David Lisle, that he was close to death. Sharp took Strong to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where he had to spend four months recovering from his injuries. Strong told Sharp how Lisle, had brought him to England from Barbados. Lisle had apparently been dissatisfied with Strong's services and after beating him with his pistol, had thrown him onto the streets.

After Jonathan Strong had regained his health, David Lisle paid two men to recapture him. When Sharp heard the news he took Lisle to court claiming that as Strong was in England he was no longer a slave. However, it was not until 1768 that the courts ruled in Strong's favour. The case received national publicity and Sharp was able to use this in his campaign against slavery.

Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997) has pointed out: "Sharp put this matter further to the test in the case of the slave Thomas Lewis, who, belonging to a West Indian planter, escaped in Chelsea. When he was recaptured, and shipped to begin the journey to Jamaica, Sharp served the captain on his boat with a writ of habeas corpus. The case came before Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, who put to the jury the question whether the master had established his claim to the slave as his property. If they decided affirmatively, he would rule whether such a property could persist in England. The jury decided that the master had not established his claim. So the main question was left unsettled. Lord Mansfield said, rather curiously, that he hoped that the question whether slaves could be forcibly shipped back to the plantations would never be discussed."

In 1769 Sharp published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery. Soon afterwards he began to correspond and collaborate with the Quaker abolitionist Anthony Benezet and the Philadelphia abolitionist Benjamin Rush. He also took up the cases of other slaves such as James Somersett, and convinced the courts that "as soon as any slave sets foot upon English territory, he becomes free."

Granville Sharp developed radical political opinions about other issues as well. He argued in favour of parliamentary reform and an increase in the low wages paid to farm labourers. Sharp also supported the American colonists against the British government and as a result, had to resign from the civil service in 1776.

In April 1780 John Cartwright helped establish the Society for Constitutional Information. Granville Sharp joined the organisation. Other members included John Horne Tooke, John Thelwall, Granville Sharp, Josiah Wedgwood, Joseph Gales and William Smith. It was an organisation of social reformers, many of whom were drawn from the rational dissenting community, dedicated to publishing political tracts aimed at educating fellow citizens on their lost ancient liberties. It promoted the work of Tom Paine and other campaigners for parliamentary reform. Sharp's biographer, Grayson Ditchfield, has pointed out that "Sharp corresponded with Christopher Wyvill, John Jebb, and other reformers; he wrote strongly against triennial parliaments as an insufficient measure; and he supported the legislative independence of the Irish parliament. In the belief that the ancient constitution represented people rather than property, and as an alternative to the universal suffrage for which he was not an enthusiast, Sharp advocated a revival of the Anglo-Saxon system of frankpledge. It would involve a system of administration from tithing courts to parliament, which would secure the involvement in government, and the preservation of the rights, of an active citizenry."

In June 1786 Thomas Clarkson published Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African. As Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "A substantial book (256 pages), it traced the history of slavery to its decline in Europe and arrival in Africa, made a powerful indictment of the slave system as it operated in the West Indian colonies and attacked the slave trade supporting it. In reading it, one is struck by its raw emotion as much as by its strong reasoning." William Smith argued that the book was a turning-point for the slave trade abolition movement and made the case "unanswerably, and I should have thought, irresistibly".

During this period Sharp became interested in another issue. In 1786 Jonas Hanway established the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor. This was an attempt to help black people living in London who had been victims of the slave trade. Simon Schama has argued in Rough Crossings: Britain, the Slaves and Empire (2005) that the harsh winter of 1785-86 was one of the factors that encouraged Hanway to do something for the significant number of Africans living in poverty: "In the East End and Rotherhithe: tattered bundles of human misery, huddled in doorways, shoeless, sometimes shirtless even in the bitter cold or else covered with filthy rags."

Granville Sharp came up with the idea that this black community should be allowed to to start a colony of free slaves in Sierra Leone. The country was chosen largely on the strength of evidence from the explorer, Mungo Park and a encouraging report from the botanist, Henry Smeathman, who had recently spent three years in the area. The British government supported Sharp's plan and agreed to give £12 per African towards the cost of transport. Sharp contributed more than £1,700 to the venture. Others who invested in what became known as the Sierra Leone Company, included William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Samuel Whitbread, William Smith and Henry Thornton.

Richard S. Reddie, the author of Abolition! The Struggle to Abolish Slavery in the British Colonies (2007) has argued: "Some detractors have since denounced the Sierra Leone project as repatriation by another name. It has been seen as a high-minded yet hypocritical way of ridding the country of its rising black population... Some in Britain wanted Africans to leave because they feared they were corrupting the virtues of the country's white women, while others were tired of seeing them reduced to begging on London streets."

Granville Sharp was able to persuade a small group of London's poor to travel to Sierra Leone in 1787. As Hugh Thomas, the author of The Slave Trade (1997), has pointed out: "A ship was charted, the sloop-of-war Nautilus was commissioned as a convoy, and on 8th April the first 290 free black men and 41 black women, with 70 white women, including 60 prostitutes from London, left for Sierra Leone under the command of Captain Thomas Boulden Thompson of the Royal Navy". When they arrived they purchased a stretch of land between the rivers Sherbo and Sierra Leone.

The settlers sheltered under old sails, donated by the navy. They named the collection of tents Granville Town after the man who had made it all possible. Granville Sharp wrote to his brother that "they have purchased twenty miles square of the finest and most beautiful country... that was ever seen... fine streams of fresh water run down the hill on each side of the new township; and in the front is a noble bay."

The reality was very different. Adam Hochschild, the author of Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2005) has argued: "The expedition's delayed departure from England meant that it had arrived on the African coast in the midst of the malarial rainy season.... The ground was another major problem: steep, forested slopes with thin topsoil... When they managed to coax a few English vegetables out of the ground, ants promptly devoured the leaves."

Soon after arriving the colony suffered from an outbreak of malaria. In the first four months alone, 122 died. One of the white settlers wrote to Sharp: "I am very sorry indeed, to inform you, dear Sir, that... I do not think there will be one of us left at the end of a twelfth month... There is not a thing, which is put into the ground, will grow more than a foot out of it... What is more surprising, the natives die very fast; it is quite a plague seems to reign here among us."

Adam Hochschild has pointed out: "As supplies at Granville Town dwindled and crops failed, the increasingly frustrated settlers turned to the long-time mainstay of the local economy, the slave trade.... Three white doctors from Granville Town ended up at the thriving slave depot... at Bance Island." Granville Sharp was furious when he discovered what was happening and wrote to the settlers: "I could not have conceived that men who were well aware of the wickedness of slave dealing, and had themselves been suffers (or at least many of them) under the galling yoke of bondage to slave-holders... should become so basely depraved as to yield themselves instruments to promote, and extend, the same detestable oppression over their brethren."

In 1787 Sharp, Thomas Clarkson and William Dillwyn formed the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee, were Quakers. This included John Barton (1755-1789); George Harrison (1747-1827); Samuel Hoare Jr. (1751-1825); Joseph Hooper (1732-1789); John Lloyd (1750-1811); Joseph Woods (1738-1812); James Phillips (1745-1799) and Richard Phillips (1756-1836). Influential figures such as John Wesley, Josiah Wedgwood, James Ramsay, and William Smith gave their support to the campaign.

Granville Sharp was appointed as chairman. He accepted the title but never took the chair. Clarkson commented that Sharp "always seated himself at the lowest end of the room, choosing rather to serve the glorious cause in humility... than in the character of a distinguished individual." Clarkson was appointed secretary and Hoare as treasurer. At their second meeting Hoare reported subscriptions of £136.

Thomas Clarkson approached another sympathiser, Charles Middleton, the MP for Rochester, to represent the group in the House of Commons. He rejected the idea and instead suggested the name of William Wilberforce, the MP for Hull, who "not only displayed very superior talents of great eloquence, but was a decided and powerful advocate of the cause of truth and virtue." Lady Middleton wrote to Wilberforce who replied: "I feel the great importance of the subject and I think myself unequal to the task allotted to me, but yet I will not positively decline it." Wilberforce's nephew, George Stephen, was surprised by this choice as he considered him a lazy man: "He worked out nothing for himself; he was destitute of system, and desultory in his habits; he depended on others for information, and he required an intellectual walking stick."

Charles Fox was unsure of Wilberforce's commitment to the anti-slavery campaign. He wrote to Thomas Walker: "There are many reasons why I am glad (Wilberforce) has undertaken it rather than I, and I think as you do, that I can be very useful in preventing him from betraying the cause, if he should be so inclined, which I own I suspect. Nothing, I think but such a disposition, or a want of judgment scarcely credible, could induce him to throw cold water upon petitions. It is from them and other demonstrations of the opinion without doors that I look for success."

In May 1788, Charles Fox precipitated the first parliamentary debate on the issue. He denounced the "disgraceful traffic" which ought not to be regulated but destroyed. He was supported by Edmund Burke who warned MPs not to let committees of the privy council do their work for them. William Dolben described shipboard horrors of slaves chained hand and foot, stowed like "herrings in a barrel" and stricken with "putrid and fatal disorders" which infected crews as well. With the support of Wilberforce Samuel Whitbread, Charles Middleton and William Smith, Dolben put forward a bill to regulate conditions on board slave ships. The legislation was initially rejected by the House of Lords but after William Pitt threatened to resign as prime minister, the bill passed 56 to 5 and received royal assent on 11th July.

Another debate on the slave trade took place the following year. On 12th May 1789 William Wilberforce made his first speech on the subject. Wilberforce's biographer, John Wolffe, has pointed out: "Following the publication of the privy council report on 25 April 1789, Wilberforce marked his own delayed formal entry into the parliamentary campaign on 12 May with a closely reasoned speech of three and a half hours, using its evidence to describe the effects of the trade on Africa and the appalling conditions of the middle passage. He argued that abolition would lead to an improvement in the conditions of slaves already in the West Indies, and sought to answer the economic arguments of his opponents. For him, however, the fundamental issue was one of morality and justice. The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was very pleased with the speech and sent its thanks for his "unparalleled assiduity and perseverance".

The House of Commons agreed to establish a committee to look into the slave trade. Wilberforce said he did not intend to introduce new testimony as the case against the trade was already in the public record. Ellen Gibson Wilson, a leading historian on the slave trade has argued: "Everyone thought the hearing would be brief, perhaps one sitting. Instead, the slaving interests prolonged it so skilfully that when the House adjourned on 23 June, their witnesses were still testifying."

Sharp continued to refuse to accept the negative reports coming from Sierra Leone. He wrote that he had chosen "the most eligible spot for... settlement on the whole coast of Africa". With the financial support of William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Samuel Whitbread, Sharp dispatched another shipload of black and white settlers and supplies. It was not long before Sharp began receiving reports that many of the new settlers were "wicked enough to go into the service of the slave trade".

In 1789, a Royal Navy warship making its down the coast fired a shot that set a Sierra Leone village on fire. The local chief took revenge by giving the settlers three days to depart, and then burning Granville Town to the ground. The remaining settlers were rescued by the slave traders on Bance Island. Sharp was devastated when he discovered that the last of the men he had sent to Africa were now also involved in the slave trade.

Thomas Clarkson suggested to Granville Sharp that Alexander Falconbridge should be sent to Sierra Leone. Falconbridge was appointed as a commercial agent with a £300 salary. He took a large number of gifts paid for by the Sierra Leone Company. Soon after arriving he used these gifts to persuade the local chiefs to let the settlers reoccupy their overgrown land. Falconbridge's wife, Anna Maria, was concerned about the job facing her husband. "It was surely a premature, hair-brained, and ill digested scheme, to think of sending such a number of people all at once, to a rude, barbarous and unhealthy country, before they were certain of possessing an acre of land."

They now sent John Clarkson, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where there was a community of former American slaves who had fought for the British in the War of Independence, to recruit settlers for the abolitionist colony. With the support of Thomas Peters, the black loyalist leader, he led a fleet of fifteen vessels, carrying 1196 settlers, to Sierra Leone, which they reached on 6th March, 1792. Although sixty-five of the Nova Scotians died during the voyage, they continued to support Clarkson who they called "their Moses".

William Wilberforce believed that the support for the French Revolution by the leading members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade such as Sharp was creating difficulties for his attempts to bring an end to the slave trade in the House of Commons. He told Thomas Clarkson: "I wanted much to see you to tell you to keep clear from the subject of the French Revolution and I hope you will." Isaac Milner, after a long talk with Clarkson, commented to Wilberforce: "I wish him better health, and better notions in politics; no government can stand on such principles as he maintains. I am very sorry for it, because I see plainly advantage is taken of such cases as his, in order to represent the friends of Abolition as levellers."

On 18th April 1791 Wilberforce introduced a bill to abolish the slave trade. Wilberforce was supported by William Pitt, William Smith, Charles Fox, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, William Grenville and Henry Brougham. The opposition was led by Lord John Russell and Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the MP for Liverpool. One observer commented that it was "a war of the pigmies against the giants of the House". However, on 19th April, the motion was defeated by 163 to 88.

John Clarkson became governor of the colony that was appropriately named as Freetown. However, as Hugh Brogan has argued: "It was the understanding between Clarkson and the Nova Scotians that got the colony through its very difficult first year. Clarkson's services were at first generally recognized. But great strains arose between him and the company directors, partly religious (he was not sympathetic to the insistent evangelicalism of Henry Thornton, the company chairman), partly because of the usual tension between head office and the man on the spot, and above all because Clarkson insisted on putting the views and interests of the Nova Scotians first, whereas the directors wanted the enterprise to show an early profit, so that they could compete successfully with the slave traders and bring to Africa Christianity." Clarkson was dismissed as governor on 23rd April 1793.

In March 1796, Wilberforce's proposal to abolish the slave trade was defeated in the House of Commons by only four votes. At least a dozen abolitionist MPs were out of town or at the new comic opera in London. Wilberforce wrote in his diary: "Enough at the Opera to have carried it. I am permanently hurt about the Slave Trade." Thomas Clarkson commented: "To have all our endeavours blasted by the vote of a single night is both vexatious and discouraging." It was a terrible blow to Clarkson and he decided to take a rest from campaigning against the slave trade.

Sharp and other social reformers became extremely unpopular when they supported the French Revolution. According to Grayson Ditchfield: "In common with many radicals Sharp compared the state of slavery to that of political reformers allegedly repressed by an unjust government in his own country. Like them, too, he was more concerned with constitutional issues than with the social grievances of the poor in Britain."

In 1804, Thomas Clarkson returned to his campaign against the slave trade and toured the country on horseback obtaining new evidence and maintaining support for the campaigners in Parliament. A new generation of activists such as Henry Brougham, Zachary Macaulay and James Stephen, helped to galvanize older members of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

William Wilberforce introduced an abolition bill on 30th May 1804. It passed all stages in the House of Commons and on 28th June it moved to the House of Lords. The Whig leader in the Lords, Lord Grenville, said as so many "friends of abolition had already gone home" the bill would be defeated and advised Wilberforce to leave the vote to the following year. Wilberforce agreed and later commented "that in the House of Lords a bill from the House of Commons is in a destitute and orphan state, unless it has some peer to adopt and take the conduct of it".

In 1805 the bill was once again presented to the House of Commons. This time the pro-slave trade MPs were better organised and it was defeated by seven votes. Wilberforce blamed "Great canvassing of our enemies and several of our friends absent through forgetfulness, or accident, or engagements preferred from lukewarmness." Clarkson now toured the country reactivating local committees against the slave trade in an attempt to drum up the support needed to get the legislation through parliament.

In February, 1806 Lord Grenville was invited by the king to form a new Whig administration. Grenville, was a strong opponent of the slave trade. Grenville was determined to bring an end to British involvement in the trade. Thomas Clarkson sent a circular to all supporters of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade claiming that "we have rather more friends in the Cabinet than formerly" and suggested "spontaneous" lobbying of MPs.

Grenville's Foreign Secretary, Charles Fox, led the campaign in the House of Commons to ban the slave trade in captured colonies. Clarkson commented that Fox was "determined upon the abolition of it (the slave trade) as the highest glory of his administration, and as the greatest earthly blessing which it was the power of the Government to bestow." This time there was little opposition and it was passed by an overwhelming 114 to 15.

In the House of Lords Lord Greenville made a passionate speech where he argued that the trade was "contrary to the principles of justice, humanity and sound policy" and criticised fellow members for "not having abolished the trade long ago". When the vote was taken the bill was passed in the House of Lords by 41 votes to 20.

In January 1807 Lord Grenville introduced a bill that would stop the trade to British colonies on grounds of "justice, humanity and sound policy". Ellen Gibson Wilson has pointed out: "Lord Grenville masterminded the victory which had eluded the abolitionist for so long... He opposed a delaying inquiry but several last-ditch petitions came from West Indian, London and Liverpool shipping and planting spokesmen.... He was determined to succeed and his canvassing of support had been meticulous." Grenville addressed the Lords for three hours on 4th February and when the vote was taken it was passed by 100 to 34. Samuel Romilly felt it to be "the most glorious event, and the happiest for mankind, that has ever taken place since human affairs have been recorded."

Under the terms of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) British captains who were caught continuing the trade were fined £100 for every slave found on board. However, this law did not stop the British slave trade. If slave-ships were in danger of being captured by the British navy, captains often reduced the fines they had to pay by ordering the slaves to be thrown into the sea.

In July, 1807, members of the Society for the Abolition of Slave Trade established the African Institution, an organization that was committed to watch over the execution of the law, seek a ban on the slave trade by foreign powers and to promote the "civilization and happiness" of Africa. The Duke of Gloucester became the first president and members of the committee included Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, Henry Brougham, James Stephen and Zachary Macaulay.

Wayne Ackerson, the author of The African Institution and the Antislavery Movement in Great Britain (2005) has argued: "The African Institution was a pivotal abolitionist and antislavery group in Britain during the early nineteenth century, and its members included royalty, prominent lawyers, Members of Parliament, and noted reformers such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and Zachary Macaulay. Focusing on the spread of Western civilization to Africa, the abolition of the foreign slave trade, and improving the lives of slaves in British colonies, the group's influence extended far into Britain's diplomatic relations in addition to the government's domestic affairs. The African Institution carried the torch for antislavery reform for twenty years and paved the way for later humanitarian efforts in Great Britain."

Some people involved in the anti-slave trade campaign such as Thomas Fowell Buxton, argued that the only way to end the suffering of the slaves was to make slavery illegal. William Wilberforce disagreed, he believed that at this time slaves were not ready to be granted their freedom. He pointed out in a pamphlet that he wrote in 1807 that: "It would be wrong to emancipate (the slaves). To grant freedom to them immediately, would be to insure not only their masters' ruin, but their own. They must (first) be trained and educated for freedom."

Sharp joined Thomas Clarkson, Thomas Fowell Buxton, William Allen, Joseph Sturge, Thomas Walker, James Cropper, Elizabeth Pease, Anne Knight, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd and Zachary Macaulay in the campaign against slavery.

Granville Sharp, who lived mainly in Garden Court, Temple. After a gradual physical and mental decline he was not to see the final abolition of slavery as he died on 6th July, 1813.

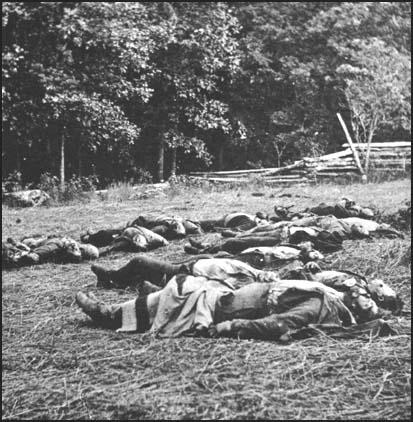

On this day in 1863 George E. Pickett, letter to his wife after the Battle of Gettysburg.

The sacrifice of life on that bloodsoaked field on the fatal 3rd was too awful for the heralding of victory, even for our victorious foe, who, I think, believe as we do, that it decided the fate of our cause. No words can picture the anguish of that roll call - the breathless waits between the responses. The "Here" of those who, by God's mercy, had miraculously escaped the awful rain of shot and shell with a sob - a gasp - a knew - for the unanswered name of his comrade called before his.

Even now I can hear them cheering as I gave the order, "Forward"! I can feel their faith and trust in me and their love for our cause. I can feel the thrill of their joyous voices as they called out all along the line, "We'll follow you, Master George. We'll follow you, we'll follow you." Oh, how faithfully they kept their word, following me on, on to their death, and I, believing in the promised support, led them on, on, on.

Oh, God! I can't write you a love letter today, my Sallie, for, with my great love for you and my gratitude to God for sparing my life to devote to you, comes the overpowering thought of those whose lives were sacrificed - of the brokenhearted widows and mothers and orphans. The moans of my wounded boys, the sight of the dead, upturned faces flood my soul with grief; and here am I, whom they trusted, whom they followed, leaving them on the field of carnage.

Infantry at Gettysburg by Timothy O'Sullivan (July, 1863)

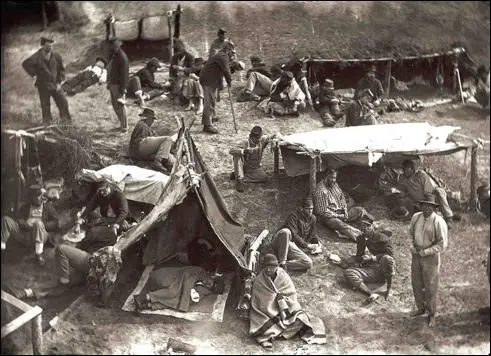

On this day in 1864 John Ranson writes about conditions in Andersonville Camp. "Boiling hot, camp reeking with filth, and no sanitary privileges; men dying off over 140 per day. Stockade enlarged, taking in eight or ten more acres, giving us more room, and stumps to dig up for wood to cook with. Jimmy Devers has been a prisoner over a year and, poor boy, will probably die soon. Have more mementos than I can carry, from those who have died, to be given to their friends at home. At least a dozen have given me letters, pictures, etc., to take North. Hope I shan't have to turn them over to someone else."

On this day in 1915 the New York Times criticises Jane Addams and the Women's Peace Party. "Everyone will be glad to welcome Miss Jane Addams back and this includes those of her admirers who were sorry to see her go. Those will hope that the next time there is to be a demonstration of the folly of those who think peace can be brought by stopping a war it will fall to the lot of someone less generally respected than she is to make it. For Miss Addams is a citizen too highly valued for any one to see her engaged in such melancholy enterprises without a feeling of pain."

On this day in 1916 Charles Repington interviews General Douglas Haig about the Battle of the Somme: "Lord Esher had arranged this trip to the Somme for me. The invitation having come, I set out and left for Amiens at this morning. I was met at the station by Colonel Hutton Wilson, who was in charge of the Press, and I put up at the Hotel du Rhin. Brigadier-General Charteris, now in charge of the Intelligence in Macdonogh's place, came to lunch, and said that I was free to go where I pleased, the only stipulation was to kill Germans. The strategic objective in this area was a secondary consideration. There were about 60 German battalions against us, and 30 against the French, when the action began on July 1. There are 120 battalions against us now, all the German troops eastward to Verdun having been milked. At present the Germans were afraid to milk their front to northward for fear lest we should make another attack there. Rawlinson was in charge of the 4th Army, which was making the attack. He had been given fifteen divisions but Gough, after the attack, had been placed in charge of the 8th and 10th Army Corps, which, with Snow's 7th Army Corps, had made the unsuccessful attack between Gommecourt and Thiepval. Since the beginning some divisions had been taken out of our line and replaced owing to the failure and losses of our attacks at Gommecourt, Thiepval and Orvillers. Charteris said we had lost 55,000 men, and put down the German losses at 75,000, which I did not believe. He is going to say officially that the Germans have lost 60,000 and says that I can safely say 50,000."

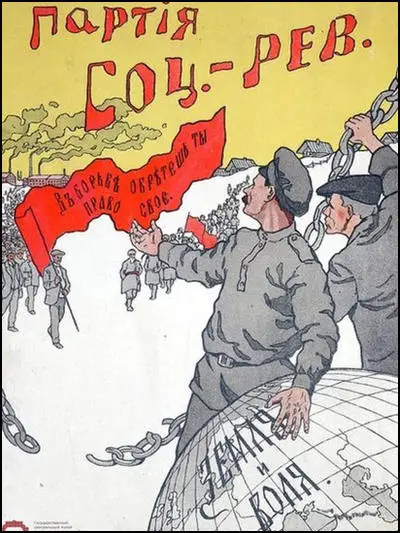

On this day in 1918 the Socialist Revolutionaries begin their attempt to overthrow the Bolsheviks. The First Congress of Soviets that was held in June, 1917, had 1,090 delegates representing more than 400 different soviets. Of these, 285 were Socialist Revolutionaries, 248 Mensheviks and 105 Bolsheviks. Soon afterwards the SRs split between those who supported the Provisional Government and the Bolsheviks who favoured a communist revolution. Those like Maria Spirdonova and Mikhail Kalinin who supported revolution became known as Left Socialist Revolutionists.

The party strongly opposed the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution. In the elections held for the Constituent Assembly in November, 1917, the SR won 20,900,000 votes (58 per cent), whereas the Bolsheviks won only 9,023,963 votes (25 per cent).

In 1918 the Soviet government closed down the Constituent Assembly and banned the SR and other anti-Bolshevik parties. Some SRs now resorted to acts of terrorism. On 30th August, 1918, Vladimir Lenin was shot by Dora Kaplan and soon afterwards Moisei Uritsky, Commissar for Internal Affairs in the Northern Region, was assassinated by another supporter of the SR.

On this day in 1923 Crystal Eastman, published an article in Time and Tide on a comment made by Sidney Webb at the Labour Party Conference:

It is very unlikely that all the delegates to the recent British Labour Party Conference agreed with Mr. Sidney Webb when he declared in his presidential address that "Robert Owen and not Karl Marx was the founder of British Socialism." The true believers might well have replied, "There is no British Socialism. There is only Socialism and it is international." But there was no spoken protest and Mr. Webb's able address, with its insistence on political democracy and a gradual

progress, with its emphasis on "brotherhood" and consequent disavowal of the class war, was allowed to stand as the keynote utterance of the conference. Sudden increase in power and responsibility have had their usual effect; these Labour Party leaders seem to walk a bit soberly today, as though they feared they might wake up some morning and find the destinies of the Empire actually in their hands.

The conference was considerably enlivened by the expulsion of four Scottish members from Parliament, and it was enormously cheered and heartened by the opportunity to welcome Robert Smillie as a Labour M.P. It is the general opinion that Mr. Smillie will help to give unity and coherence to His Majesty's Opposition. There is such confidence in his honesty and intelligence on all sides, that he may even be able to reconcile the emotional Scotch extremists and the parliamentarians. It is felt that if Mr. Smillie believed certain "economies" meant the death of little children he would be quite capable of calling a man who urged them a murderer bur that he would know how to do it in parliamentary language.

On this day in 1943 Winston Churchill sends memorandums to the Chiefs of Staff and asks permission to use poison gas on Germany. "I may certainly have to ask you to support me in using poison gas. We could drench the cities of the Ruhr and many other cities in Germany in such a way that most of the population would be requiring constant medical attention... If we do it one hundred per cent. In the meanwhile, I want the matter studied in cold blood by sensible people and not by that particular set of psalm-singing uniformed defeatists which one runs across now here now there."

On this day in 1960 Aneurin Bevan died of cancer.

Neville Chamberlain resigned and on 10th May, 1940, George VI appointed Winston Churchill as prime minister. Later that day the German Army began its Western Offensive and invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg. Two days later German forces entered France.

Churchill formed a coalition government and placed leaders of the Labour Party such as Clement Attlee (Deputy Prime Minister), Ernest Bevin (Minister of Labour), Herbert Morrison (Home Secretary), Stafford Cripps (Minister of Aircraft Production), Arthur Greenwood (Minister without Portfolio) and Hugh Dalton (Minister of Economic Warfare) in key positions. He also brought in another long-time opponent of Chamberlain, Anthony Eden, as his secretary of state for war.

Bevan condemned Churchill's decision to keep leading appeasers such as Neville Chamberlain (Lord President of the Council), Lord Halifax (Foreign Secretary), Kingsley Wood (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and John Simon (Lord High Chancellor) in senior positions in the government. He argued that Bevin and Morrison were the right men for their posts "yet Labour was only being allowed to put petrol in the car: the Tories still held the steering wheel."

Once Churchill was in power, Bevan used his influence as editor of Tribune and the leader of the left-wing MPs in the House of Commons, to shape government policies. Bevan opposed the heavy censorship imposed on radio and newspapers and wartime Regulation 18B that gave the Home Secretary the powers to lock up citizens without trial. When the government banned the Daily Worker he argued that the newspaper was "detestable but harmless" and the real reason for its suppression was that it was "intended to serve as an instrument of intimidation against the Press as a whole".

John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) has argued: "There was a lot of fine talk about democracy during the war and a good deal of national self-congratulation that the forms of parliamentary government were maintained; but after the formation of the Coalition in May 1940 there was no regular opposition in the House of Commons except that offered by a few maverick malcontents of whom Bevan was increasingly the most prominent and by far the most consistent."

Bevan believed that the Second World War would give Britain the opportunity to create a new society. He often quoted Karl Marx who had said in 1885: "The redeeming feature of war is that it puts a nation to the test. As exposure to the atmosphere reduces all mummies to instant dissolution, so war passes supreme judgment upon social systems that have outlived their vitality." At the beginning of the 1945 General Election campaign Bevan told his audience: "We have been the dreamers, we have been the sufferers, now we are the builders. We enter this campaign at this general election, not merely to get rid of the Tory majority. We want the complete political extinction of the Tory Party."

In its manifesto, Let us Face the Future, it made clear that "the Labour Party is a Socialist Party, and proud of it. Its ultimate purpose at home is the establishment of the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain - free, democratic, efficient, progressive, public-spirited, its material resources organised in the service of the British people.... Housing will be one of the greatest and one of the earliest tests of a Government's real determination to put the nation first. Labour's pledge is firm and direct - it will proceed with a housing programme with the maximum practical speed until every family in this island has a good standard of accommodation. That may well mean centralising and pooling of building materials and components by the State, together with price control. If that is necessary to get the houses as it was necessary to get the guns and planes, Labour is ready."

The manifesto argued for the state takeover of certain branches of the economy - the Bank of England, coal mines, electricity and gas, railways, and iron and steel. This reflected some of the measures passed by the Labour Conference in December 1944. However, some left-wing commentators pointed out that the "nationalisation measures were justified on grounds of economic efficiency, not as a means of shifting the balance between labour and capital."

The document made it clear that if elected it would pass legislation to protect the working-class: "The Labour Party stands for freedom - for freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of the Press. The Labour Party will see to it that we keep and enlarge these freedoms, and that we enjoy again the personal civil liberties we have, of our own free will, sacrificed to win the war. The freedom of the Trade Unions, denied by the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act, 1927, must also be restored. But there are certain so-called freedoms that Labour will not tolerate: freedom to exploit other people; freedom to pay poor wages and to push up prices for selfish profit; freedom to deprive the people of the means of living full, happy, healthy lives".

The Labour Party also stated its commitment to a National Health Service: "By good food and good homes, much avoidable ill-health can be prevented. In addition the best health services should be available free for all. Money must no longer be the passport to the best treatment. In the new National Health Service there should be health centres where the people may get the best that modern science can offer, more and better hospitals, and proper conditions for our doctors and nurses. More research is required into the causes of disease and the ways to prevent and cure it. Labour will work specially for the care of Britain's mothers and their children - children's allowances and school medical and feeding services, better maternity and child welfare services. A healthy family life must be fully ensured and parenthood must not be penalised if the population of Britain is to be prevented from dwindling."

On 4th June, 1945, Winston Churchill made a radio broadcast where he attacked Clement Attlee and the Labour Party: "I must tell you that a socialist policy is abhorrent to British ideas on freedom. There is to be one State, to which all are to be obedient in every act of their lives. This State, once in power, will prescribe for everyone: where they are to work, what they are to work at, where they may go and what they may say, what views they are to hold, where their wives are to queue up for the State ration, and what education their children are to receive. A socialist state could not afford to suffer opposition - no socialist system can be established without a political police. They (the Labour government) would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo."

Ian Mikardo believed that the Churchill broadcast helped his election campaign: "In his first election broadcast on the radio he warned the country that if they elected a Labour government they would find themselves under the jackboots of a socialist gestapo. The British people just wouldn't take that. They looked at Clem Attlee, the timid, correct, undemonstrative, unaggressive ex-public-schoolboy, ex-major, and couldn't see an Adolf Hitler in him."

Attlee's response the following day caused Churchill serious damage: "The Prime Minister made much play last night with the rights of the individual and the dangers of people being ordered about by officials. I entirely agree that people should have the greatest freedom compatible with the freedom of others. There was a time when employers were free to work little children for sixteen hours a day. I remember when employers were free to employ sweated women workers on finishing trousers at a penny halfpenny a pair. There was a time when people were free to neglect sanitation so that thousands died of preventable diseases. For years every attempt to remedy these crying evils was blocked by the same plea of freedom for the individual. It was in fact freedom for the rich and slavery for the poor. Make no mistake, it has only been through the power of the State, given to it by Parliament, that the general public has been protected against the greed of ruthless profit-makers and property owners. The Conservative Party remains as always a class Party. In twenty-three years in the House of Commons, I cannot recall more than half a dozen from the ranks of the wage earners. It represents today, as in the past, the forces of property and privilege. The Labour Party is, in fact, the one Party which most nearly reflects in its representation and composition all the main streams which flow into the great river of our national life."

Labour candidates pointed out that the government had used state control and planning during the Second World War. During the election campaign Labour candidates argued that without such planning Britain would never have won the war. Sarah Churchill told her father in June, 1945: "Socialism as practised in the war did no one any harm, and quite a lot of people good." Arthur Greenwood argued that state planning had proved its value in wartime and would be necessary in peacetime.

When the poll closed the ballot boxes were sealed for three weeks to allow time for servicemen's votes (1.7 million) to be returned for the count on 26th July. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. It came as a surprise that Winston Churchill, who was considered to be the most important figure in winning the war, suffered a landslide defeat. Harold Macmillan commented: "It was not Churchill who lost the 1945 election; it was the ghost of Neville Chamberlain."

Henry (Chips) Channon recorded in his diary what happened on the first day of the new Parliament: "I went to Westminster to see the new Parliament assemble, and never have I seen such a dreary lot of people. I took my place on the Opposition side, the Chamber was packed and uncomfortable, and there was an atmosphere of tenseness and even bitterness. Winston staged his entry well, and was given the most rousing cheer of his career, and the Conservatives sang 'For He's a Jolly Good Fellow'. Perhaps this was an error in taste, though the Socialists went one further, and burst into the 'Red Flag' singing it lustily; I thought that Herbert Morrison and one or two others looked uncomfortable."

Clement Attlee, Herbert Morrison and Ernest Bevin, the senior figures in the government, were all on the right of the party. The new intake of MPs included far fewer from working-class backgrounds. According to one historian, "with apparent satisfaction the new prime minister noted that he had appointed no fewer than twenty-eight public school boys, including seven Etonians, five Haileyburians and four Winchester men, to the government."

The most significant figure on the left was Aneurin Bevan. He argued for a comprehensive programme of nationalisation as without state control, there could be no true socialism because there could be no planning: "In practice it is impossible for the modern State to maintain an independent control over the decisions of big business. When the State extends its control over big business, big business moves in to control the State. The political decisions of the State become so important a part of the business transactions of the combines that is the law of their survival that those decisions should suit the needs of profit-making. The State ceases to be the umpire. It becomes the prize."

Attlee was also not enthusiastic about the nationalisation programme proposed by Ian Mikardo at the 1944 Labour Conference and in the Labour manifesto, Let us Face the Future. However, it now had the support of the vast majority of its membership and he agreed to put it into operation. As Hugh Dalton pointed out: "We weren't really beginning our Socialist programme until we had gone past all the utility junk - such as transport and electricity - which were publicly owned in every capitalist country in the world. Practical Socialism... really began with Coal and Iron and Steel, and there was a strong political argument for breaking the power of a most dangerous body of capitalists."

Herbert Morrison, the deputy prime minister, had always been strongly opposed to the nationalisation of Iron and Steel. He began negotiations with Sir Andrew Duncan, chairman of the British Iron and Steel Federation, in order to avoid it being taken into public ownership. Aneurin Bevan responded by arguing that the Labour government should keep its manifesto's commitment: "Suggestions will be made that some parts of the industry are efficient and satisfactory and so should be left alone, but I am opposed to the Government taking over the cripples and leaving the good things to private ownership."

A few weeks later, Bevan argued: "Democracy means that if you hurt people they have the right to squeal. But when you hear the squeals you must carefully find out who is squealing. If the right people are squealing then we are doing the job properly... So far we have been all right and here is the whole delusion of coalition of national co-operation. You cannot focus the full national will on the main evils of society, because in a coalition there are people who benefit from the very evils themselves."

After the 1945 General Election, Clement Attlee, the new Labour Prime Minister, appointed Bevan as Minister of Health. According to John Campbell, the author of Nye Bevan and the Mirage of British Socialism (1987) it was "a remarkable appointment for Attlee to bring Bevan straight into the Cabinet as Minister of Health - by far the boldest stroke in a generally cautious exercise in rewarding the long-serving party faithful." At forty-seven Bevan was by some years the youngest member of a Cabinet whose average age was over sixty."

In 1946 Parliament introduced the revolutionary National Insurance Act. It instituted a comprehensive state health service, effective from 5th July 1948. The Act provided for compulsory contributions for unemployment, sickness, maternity and widows' benefits and old age pensions from employers and employees, with the government funding the balance. It promised an all-embracing social insurance scheme from the "cradle to the grave", a system which would give people benefits as of right, and without a means test.

The government announced plans for a National Health Service that would be, "free to all who want to use it." The legislation established "a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement in the physical and mental health of the people of England and Wales and the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of illness and for that purpose to provide or secure the effect of provision of services."

Some members of the medical profession opposed the government's plans. Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA) mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. The main complaint of the BMA was that the NHS would "turn doctors from free-thinking professionals into salaried servants of central government".

The right-wing national press was opposed to the idea of a National Health Service. The Daily Sketch reported: "The State medical service is part of the Socialist plot to convert Great Britain into a National Socialist economy. The doctors' stand is the first effective revolt of the professional classes against Socialist tyranny. There is nothing that Bevan or any other Socialist can do about it in the shape of Hitlerian coercion."

Winston Churchill led the attack on Bevan. In one debate in the House of Commons he argued that unless Bevan "changes his policy and methods and moves without the slightest delay, he will be as great a curse to his country in time of peace as he was a squalid nuisance in time of war." The Conservative Party voted against the measure. The Tory ammendment stated that it "declines to give a Third Reading to a Bill which discourages voluntary effort and association; mutilates the structure of local government; dangerously increases minisaterial power and patronage; approppriates trust funds and benefactions in contempt of the wishes of donors and subscribers; and undermines the freedom and independence of the medical profession to the detriment of the nation." However, on 2th July, 1946, the Third Reading was carried by 261 votes to 113. Michael Foot commented that the Conservatives had voted against the "most exciting and popular of the Government's measures a bare four months before it was to be introduced".

David Widgery, the author of The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988) admitted that "the Act was bold in outline; a National Health Service entirely free at the time of use, financed out of general taxation and able to organise preventive medicine, research and paramedical aids on a national basis... Bevan himself was apparently well prepared to deal with conservative pressures, and he was quite prepared for the out-break of near-hysteria by doctors, skilfully orchestrated by Charles Hill of the BMA, who had endeared himself to the listening public during the war as the smooth-spoken, concerned Radio Doctor."

Between 1946 and its introduction in 1948, the British Medical Association (BMA), led by Charles Hill, mounted a vigorous campaign against this proposed legislation. In one survey of doctors carried out in 1948, the BMA claimed that only 4,734 doctors out of the 45,148 polled, were in favour of a National Health Service. One doctor was cheered at a BMA meeting for saying that the proposed NHS bill was "strongly suggestive" of what had been going in Nazi Germany.

By July 1948, Aneurin Bevan had guided the National Health Service Act safely through Parliament. The Government resolution was carried by 337 votes to 178. Niall Dickson has pointed out: "The UK's National Health Service (NHS) came into operation at midnight on the fourth of July 1948. It was the first time anywhere in the world that completely free healthcare was made available on the basis of citizenship rather than the payment of fees or insurance premiums... Life in Britain in the 30s and 40s was tough. Every year, thousands died of infectious diseases like pneumonia, meningitis, tuberculosis, diphtheria, and polio. Infant mortality - deaths of children before their first birthday - was around one in 20, and there was little the piecemeal healthcare system of the day could do to improve matters. Against such a background, it is difficult to overstate the impact of the introduction of the National Health Service (NHS). Although medical science was still at a basic stage, the NHS for the first time provided decent healthcare for all - and, at a stroke, transformed the lives of millions."

The Manchester Guardian commented on the passing of the National Health Service Act: "These two reforms have sometimes been greeted as a large installment of Socialism in this country. They are not strictly that, for many besides Socialists have contributed something to them. What they mark is rather an advance of the equalitarianism which has been the mainspring, though not the exclusive possession, of the British Labour movement. They are designed to offset as far as they can the inequalities that arise from the chances of life, to ensure that a "bad start" or a stroke of bad luck, illness or accident or loss of work, does not carry the heavy, often crippling, economic penalty it has carried in the past. It is important to realise the fundamental change in attitude which this implies, and its consequences for our social evolution."

In October 1950, Clement Attlee promoted Hugh Gaitskell to chancellor of the exchequer. Aneurin Bevan considered Gaitskell as hostile to the National Health Service and sent a letter to Attlee commenting: "I feel bound to tell you that for my part I think the appointment of Gaitskell to be a great mistake. I should have thought myself that it was essential to find out whether the holder of this great office would commend himself to the main elements and currents of opinion in the Party. After all, the policies which he will have to propound and carry out are bound to have the most profound and important repercussions throughout the movement."

One of Gaitskell's first tasks was to balance the budget. The National Insurance Act created the structure of the Welfare State and after the passing of the National Health Service Act in 1948, people in Britain were provided with free diagnosis and treatment of illness, at home or in hospital, as well as dental and ophthalmic services. Michael Foot, the author of Aneurin Bevan (1973) has argued: "On the afternoon of 10th April he (Hugh Gaitskell) presented his Budget, including the proposal to save £13 million - £30 million in a full year-by imposing charges on spectacles and on dentures supplied under the Health Service. And glancing over his shoulder at the benches behind him he had seemed to underline his resolve: having made up his mind, he said, a Chancellor 'should stick to it and not be moved by pressure of any kind, however insidious or well-intentioned'. Bevan did not take his accustomed seat on the Treasury bench, but listened to this part of the speech from behind the Speaker's chair, with Jennie Bevan by his side. A muffled cry of 'shame' from her was the only hostile demonstration Gaitskell received that afternoon."

The following day, Aneurin Bevan resigned from the government. In a speech he made in the House of Commons he explained why he had made this decision: "The Chancellor of the Exchequer in this year's Budget proposes to reduce the Health expenditure by £13 million - only £13 million out of £4,000 million... If he finds it necessary to mutilate, or begin to mutilate, the Health Services for £13 million out of £4,000 million, what will he do next year? Or are you next year going to take your stand on the upper denture? The lower half apparently does not matter, but the top half is sacrosanct. Is that right?... The Chancellor of the Exchequer is putting a financial ceiling on the Health Service. With rising prices the Health Service is squeezed between that artificial figure and rising prices. What is to be squeezed out next year? Is it the upper half? When that has been squeezed out and the same principle holds good, what do you squeeze out the year after? Prescriptions? Hospital charges? Where do you stop?"

Bevan went on to argue that this measure was undermining the Welfare State: " Friends, where are they going? Where am I going? I am where I always was. Those who live their lives in mountainous and rugged countries are always afraid of avalanches, and they know that avalanches start with the movement of a very small stone. First, the stone starts on a ridge between two valleys - one valley desolate and the other valley populous. The pebble starts, but nobody bothers about the pebble until it gains way, and soon the whole valley is overwhelmed. That is how the avalanche starts, that is the logic of the present situation, and that is the logic my right honourable friends cannot escape.... After all, the National Health Service was something of which we were all very proud, and even the Opposition were beginning to be proud of it. It only had to last a few more years to become a part of our traditions, and then the traditionalists would have claimed the credit for all of it. Why should we throw it away? In the Chancellor's Speech there was not one word of commendation for the Health Service - not one word. What is responsible for that?"

Bevan served for a short period as Minister of Labour in 1951 but resigned on 21st April with Harold Wilson and John Freeman when Hugh Gaitskell, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that he intended to introduce measures that would force people to pay half the cost of dentures and spectacles and a one shilling prescription charge. For the next five years Bevan was the leader of the left-wing of the Labour Party. Bevan's Tribune group criticised high defence expenditure (especially over nuclear weapons) and opposed the reformist policies of Clement Attlee.

Bevan's radicalism was less marked after 1956 when he agreed to serve the new leader, Hugh Gaitskell, as shadow foreign secretary. In October, 1957 he decided to make a speech against unilateral nuclear disarmament at the party conference. His wife, Jennie Lee, disagreed strongly with his decision: "I did not argue with him that evening, he had to be left in peace to work things out for himself, but he was in no doubt that I would have preferred him to take the easy way. I dreaded the violence of the Conference atmosphere which I knew would be generated by the dedicated advocates of immediate unilateral nuclear disarmament, but, like Nye, I did not foresee the bitterness of the personal attacks made by some delegates who ought to have known him well enough not to have doubted his motives. Disagreement was one thing: character assassination another. Were these his friends? Were these his comrades he had fought for over so many years? Could they really believe that he was a small-time career politician prepared to sacrifice his principles in order to become second-in-command to the right-wing leader of the Party?

Bevan later recalled: "I knew this morning that I was going to make a speech that would offend and even hurt many of my friends. I know that you are deeply convinced that the action you suggest is the most effective way of influencing international affairs. I am deeply convinced that you are wrong. It is therefore not a question of who is in favour of the hydrogen bomb, but a question of what is the most effective way of getting the damn thing destroyed. It is the most difficult of all problems facing mankind. But if you carry this resolution and follow out all its implications and do not run away from it you will send a Foreign Secretary, whoever he may be, naked into the conference chamber."

Aneurin Bevan became deputy leader of the Labour Party in 1959, but he was already a very ill man and died of cancer on 6th July, 1960.

of Commons, Punch Magazine (1944)