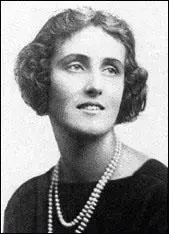

Cynthia Mosley

Cynthia Blanche Curzon, the second daughter of the foreign secretary, George Curzon, the former Conservative Party M.P and later, Viceroy of India, was born at Reigate Priory, on 23rd August 1898. Cimmie, as she was known, lived in India until 1905. Her mother, Mary Curzon died in July, 1906, and later attended school as a boarder at the Links School for Girls in Eastbourne. (1)

During the First World War she worked as a War Office clerk, earning 30s. a week, and as a land girl. She took courses in social work at the London School of Economics before utilizing her training in the East End of London. Her biographer described her as "something of a rebel against the dictates of her class". (2)

Cynthia became close to Elinor Glyn, the best-selling romantic novelist, a business woman and a couresan, who had been her father's mistress. She told her mother-substitute that she had "Bolshevik" feelings. Glyn replied: "True socialism should be to help conditions so that every child has a chance till it comes to fifteen say, and then sift the chaff from the corn." (3)

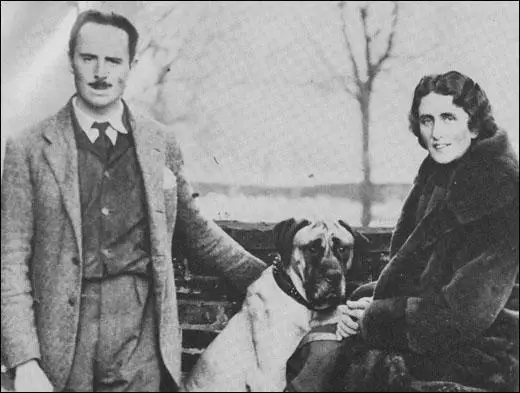

Cynthia Curzon was considered to be one of the most attractive women in Britain. According to Robert Skidelsky the "gossip columns gushed with conventional phrases about her beauty; but photographs reveal her as handsome rather than beautiful." Cynthia met, Oswald Mosley, the young Conservative Party MP while helping Nancy Astor during her by-election campaign in 1919. (4)

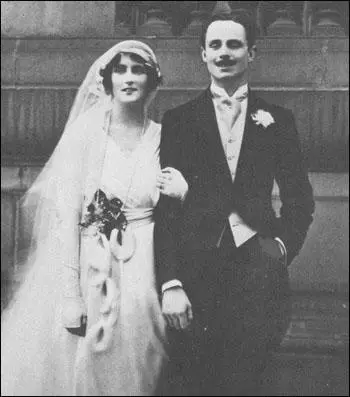

It was not until the following year that Cynthia asked her father if she could marry Mosley. "I was seated at my desk with my boxes at 11.15 p.m. when the door opened and Cimmie with her eyes alight and an air of intense excitement came into my room and asked if she might speak to me about something... She had come to ask my permission to wed young Oswald Mosley... I asked if he was gay or sedate. She replied that he had started by flirting a bit with married women but had now (at the age of 23) given that up and was full of ambition and devoted to a political career where every sort of prize awaited him." (5)

The following day Lord Curzon met Mosley for the first time: "The young man Mosley came to see me yesterday evening... Very young, tall, slim, dark, rather a big nose, little black moustache, rather a Jewish appearance... It turns out he is quite independent - has practically severed himself from his father who is a spendthrift... The estate is in the hands of trustees who will give him £8,000-£10,000 a year straight away and he will ultimately have a clear £20,000 p.a. He did not even know that Cimmie was an heiress." Curzon also asked Robert Cecil, who had worked with Mosley, what he thought of him. He replied that he was "keen, able and promising, not in the first flight, but with a good future before him". After this report Curzon commented: "I have done what I could and have no alternative but to give my consent." (6)

Cynthia Mosley

Their wedding took place on 11th May 1920 in the Chapel Royal. "Their life together started on a high note of mutual passion which was not, however, sustained. Cimmie, as she was always known, was an idealistic, emotional, not very clever woman, who idolized her husband, and wanted to be adored and cherished in return. Mosley's love for her was genuine, and fervently expressed in letters full of baby talk, written in an illegible hand. But he was incapable of fidelity, resented her minding about his love affairs, and he abused her in public for what he saw as her simplicities." Mosley had numerous affairs, including relationships with his wife's younger sister Alexandra Metcalfe (1904-1995), and with their stepmother, Grace Curzon (1879-1958). (7)

Elinor Glyn wrote to Cynthia that Oswald Mosley had a good chance of becoming prime minister and that "one day you will rule England". (8) However, he was in constant conflict with the Conservative Party and decided to stand in Harrow as an Independent in the 1922 General Election. The Labour and Liberal parties did not stand against him and he increased the size of his majority by polling 15,290 against 7,868 for the Tory candidate. However, the Conservative Party won 344 seats and formed the next government. (9)

Mosley was now in a difficult position. As his biographer pointed out: "He (Mosley) might be able to go on holding Harrow for ever, but he could scarcely expect to make his mark on his time as an eccentric Independent of mildly left-wing opinions." Attempts were made to persuade him to join the two main opposition parties. However, he was uncertain which one would give him a route to power and when Stanley Baldwin called another election in November, 1923, he decided to fight it as an Independent. He held the seat but with a reduced majority of 4,646. (10)

On 27th March 1924, Oswald Mosley applied to join the Labour Party. The Liberals reacted angrily to the decision and Margot Asquith wrote to him: "Personally I think you have done an unwise thing at a foolish time, but after all this is your own affair and not mine. You had a very great - if not the greatest chance in the future of leading the Liberal Party... You need courage and conviction to achieve anything big in politics and above all patience and a certain amount of education. Till now I have seen none of these qualities in the new Government." She finished her letter by saying she recently visited Italy: "I had a wonderful time with Mussolini who is a really Big Man." (11)

Cynthia Mosley also joined the Labour Party. They were considered to be unlikely Labour converts and were described as "'a pair of magnificent cuckoos in the Labour Party nest" but their glamour and popular Labour garden parties at their home made them celebrities within the movement (12) "They faced a bitterly hostile Conservative press and she was the likely target of the Conservative play Lady Monica Waffle's Debut (1926), about a rich society woman's left-wing pretensions. At party gatherings she stood out in her fur stole and jewellery." (13)

Beatrice Webb, a senior figure in the Labour Party, thought he was a future party leader: "We have made the acquaintance of the most brilliant man in the House of Commons - Oswald Mosley.... If there were a word for the direct opposite of a caricature, for something which is almost absurdly a perfect type, I should apply it to him. Tall and slim, his features not too handsome to be strikingly peculiar to himself, modest yet dignified in manner, with a pleasant voice and unegotistical conversation, this young person would make his way in the world without his adventitious advantages, which are many - birth, wealth and a beautiful aristocratic wife. He is also an accomplished orator in the old grand style, and an assiduous worker in the modern manner - keeps two secretaries at work supplying him with information but realizes that he himself has to do the thinking!" (14)

Smethwick By-Election

On 22nd November, John Davison, the Labour MP for Smethwick, was forced to resign on grounds of ill-health. Mosley was immediately selected to replace Davison. This was a controversial decision and some Labour politicians pointed out that the party had been formed to represent the working-class. Philip Snowden, who was opposed to Mosley's economic policies, warned the party not to "degenerate into an instrument for the ambitions of wealthy men" and suggested that some candidatures were being "put up to auction by the local Labour Party and sold to the highest bidder". (15)

Mosley also came under attack from Conservative supporting newspapers. They were at different times accused of "flaunting their wealth or adopting heavy proletarian camouflage - and which was the more reprehensible". For example, The Daily Express accused Mosley of preaching socialism "in a twenty guineas Savile Row suit". Then he was condemned for "playing his part well" in an "old overcoat and a battered hat and calling Lady Cynthia "the missus". (16)

Other newspapers wrote articles about the wealthy socialist couple frolicking on the Riviera, spending thousands of pounds in renovating their "mansion" and generally "living a debauched aristocratic life". (17) It has been claimed that these attacks motivated his supporters to work even harder. Mosley argued that: "While I am being abused by the Capitalist Press I know I am doing effective work for the Labour cause." (18)

Oswald Mosley's father joined in those criticizing the candidate. The Daily Mail published a letter from him complaining about Mosley's socialism: "More valuable help would be rendered to the country by my Socialist son and daughter-in-law if, instead of achieving cheap publicity about relinquishing titles, they would take more material action and relinquish some of their wealth and so help to make easier the plight of some of their more unfortunate followers". (19)

He followed this by giving an interview to The Daily Express. "He was born with a golden spoon in his mouth - it cost £100 in doctor's fees to bring him into the world. He lived on the fat of the land and never did a day's work in his life. If he and his wife want to go in for Labour, why don't they do a bit of work themselves? My son tells the tale that he does this and that but he lives in the height of luxury. If the working class... are going to be taken in by such nonsense - I am sorry for them. How does my son know anything about them?" (20)

Newspapers owned by Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere) and William Maxwell Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook) reported that Mosley was part of a "Red Plot" and that William Gallagher and Arthur McManus, leading members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, were campaigning for the Labour candidate. The Morning Post complained that "no tactics too contemptible for the Socialists to adopt in their grovelling appeal to all that is most stupid and most deplorable in human nature". (21)

These tactics did not stop him winning Smethwick. His majority of 6,582 on a 80% poll surprised even his most optimistic supporters. To a crowd of 8,000 outside the Town Hall he said that the result was a defeat of the Press Lords: "This is not a by-election, it is history. The result of this election sends out a message to every worker in the land. You have met and beaten the Press of reaction... Tonight all Britain looks to you and thanks you. My wonderful friends of Smethwick, by your heroic battle against a whole world in arms, I believe you have introduced a new era for British democracy." (22)

1929 General Election

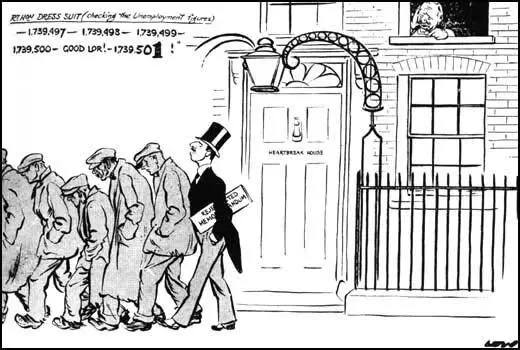

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Stanley Baldwin was urged to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May. (23)

Cynthia Mosley was selected to be the Labour Party candidate for Stoke-on-Trent. The Liberal Party candidate, John Ward, had held the seat since 1918 and in the 1924 General Election he had a 4,546 majority over his Labour opponent. During the general election of 1929 she was mocked for her "Hyde Park sentiments delivered in a Park Lane accent" (24)

The newspapers spread false stories about Cynthia. It was claimed that she had a penniless brother in America whom the heartless family allowed to live in a workhouse and that she and her husband owned a factory where they paid their workers eighteen shillings a week. Despite these attacks she got a 7,850 majority over Ward - his majority at the last election had been 4,500. She doubled the Labour vote from 13,000 to 26,000. (25) It was "the largest swing to Labour of the election and one of the largest majorities of any inter-war woman MP." (26)

In her maiden speech in the House of Commons she explained the merits of socialism and attacked the Conservative charge that unemployment insurance would "demoralize" recipients. "All my life I have got something for nothing… Some people might say I showed remarkable intelligence in the choice of my parents but I put it all down to luck… A great many people on the opposite side of the House are also in that same position… Are we demoralised? I stoutly deny that I am demoralised." (27)

Mosley Memorandum

In January 1930 unemployment in Britain reached 1,533,000. By March, the figure was 1,731,000. Oswald Mosley proposed a programme that he believed would help deal with the growing problem of unemployment in Britain. According to David Marquand: "It made three main assertions - that the machinery of government should be drastically overhauled, that unemployment could be radically reduced by a public-works programme on the lines advocated by Keynes and the Liberal Party, and that long-term economic reconstruction required a mobilisation of national resources on a larger scale than has yet been contemplated. The existing administrative structure, Mosley argued, was hopelessly inadequate. What was needed was a new department, under the direct control of the prime minister, consisting of an executive committee of ministers and a secretariat of civil servants, assisted by a permanent staff of economists and an advisory council of outside experts." (28)

The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Snowden, was a strong believer in laissez-faire economics and disliked the proposals. (29) MacDonald had doubts about Snowden's "hard dogmatism exposed in words and tones as hard as the ideas" but he also dismissed "all the humbug of curing unemployment by Exchequer grants." (30)

MacDonald passed the Mosley Memorandum to a committee consisting of Snowden, Tom Shaw, Arthur Greenwood and Margaret Bondfield. The committee reported back on 1st May. Mosley's administrative proposals, the committee claimed "cut at the root of the individual responsibilities of Ministers, the special responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the sphere of finance, and the collective responsibility of the Cabinet to Parliament". The Snowden Report went onto argue that state action to reduce unemployment was highly dangerous. To go further than current government policy "would be to plunge the country into ruin". (31)

MacDonald recorded in his diary what happened when Mosley heard the news about his proposals being rejected. "Mosley came to see me... had to see me urgently: informed me he was to resign. I reasoned with him and got him to hold his decision over till we had further conversations. Went down to Cabinet Room late for meeting. Soon in difficulties. Mosley would get away from practical work into speculative experiments. Very bad impression. Thomas light, inconsistent but pushful and resourceful; others overwhelmed and Mosley on the verge of being offensively vain in himself." (32)

Oswald Mosley was not trusted by most of his fellow MPs. One Labour Party MP, Clement Attlee, said Mosley had a habit of speaking to his colleagues "as though he were a feudal landlord abusing tenants who are in arrears with their rent". (33) John Bew described Mosley as "handsome... lithe and black and shiny... he looked like a panther but behaved like a hyena". (34)

At a meeting of Labour MPs took place on 21st May, Oswald Mosley outlined his proposals. This included the provision of old-age pensions at sixty, the raising of the school-leaving age and an expansion in the road programme. He gained support from George Lansbury and Tom Johnson, but Arthur Henderson, speaking on behalf of MacDonald, appealed to Mosley to withdraw his motion so that his proposals could be discussed in detail at later meetings. Mosley insisted on putting his motion to the vote and was beaten by 210 to 29. (35)

Mosley now resigned from the government and was replaced by Clement Attlee. It has been claimed that MacDonald was so fed up with Mosley that he looked around him and choose the "most uninteresting, unimaginative but most reliable among his backbenchers to replace the fallen angel". Winston Churchill said Attlee was "a modest little man, with plenty to be modest about". Mosley was more generous as he accepted that he had "a clear, incisive and honest mind within the limits of his range". However, he added, in agreeing to take his job, Attlee "must be reckoned as content to join a government visibly breaking the pledges on which he was elected." (36)

The New Party

It was now clear that while Ramsay MacDonald was in power, Mosley's economic ideas would never be accepted. He therefore decided he had to have his own political party. In January 1931, Sir William Morris (later Lord Nuffield), a motor-car manufacturer, gave Mosley a cheque for £50,000 to form a new political party. Further donations came from the industrialist, Wyndham Portal, and tobacco millionaire Hugo Cunliffe-Owen. The left-wing Labour MP, Aneurin Bevan, who had supported the Mosley Memorandum, argued that if you accept funding from industrialists, "you will end up as a fascist party". (37)

On 20th February, 1931, Mosley and five Labour Party MPs, Cynthia Mosley, John Strachey, Robert Forgan, Oliver Baldwin (the son of Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the Conservative Party) and William J. Brown, decided to resign from the party. William E. Allen, the Tory MP for West Belfast, and Cecil Dudgeon, the Liberal MP for Galloway, also agreed to join the New Party. However, Brown and Baldwin changed their minds and sat in the House of Commons as Independents and six months later rejoined the Labour Party. (38)

Ramsay MacDonald wrote to Cynthia complaining about her decision: "When you came in a year or two ago we gave you a very hearty welcome and assumed that you knew what was the policy of the predominant Socialist Party in this country, and that, with that knowledge, you asked us to accept you as a candidate and to go your constituency and assist you in your fight... You remain true, while all the rest of us are false... We must just tolerate your censure and even contempt; and in the spare moments we have, cast occasional glances at your pursuing your heroic role with exemplary rectitude and stiff straightness to a disastrous futility and an empty sound." (39)

Cynthia Mosley came under attack from a large number of people who had helped her get elected in the 1929 General Election. She also received a letter from the chairman of the Stoke-on-Trent constituency committee, who told her: "Whilst I have always felt you were sincere in your desire to improve the lot of the people, I think your secession from the Labour Party is a bad let-down for all those who worked so wholeheartedly for you in your contest." (40)

Other people who joined the New Party included Cyril Joad (Director of Propaganda), Harold Nicolson (editor of their journal, Action), Mary Richardson (former member of the Women's Social and Political Union), John Becket and Peter Dunsmore Howard (captain of the England national rugby union team). The New Party's first electoral contest was at Ashton-under-Lyne after the death of Albert Bellamy, the Labour MP. The candidate was Allan Young, and his election agent was Wilfred Risdon. At the by-election on 30th April, 1931, Young split the Labour vote and the Conservative candidate, John Broadbent, was elected. (41)

At a committee meeting of the New Party on 14th May 1931, Oswald Mosley urged the formation of a group young men to provide protection at political meetings from other political groups. "The Communist Party will develop a challenge in this country which will seriously alarm people here. You will in effect have the situation which arose in Italy and other countries and which summoned into existence the modern movement which now rules in those countries. We have to build and create the skeleton of an organisation so as to meet it when the time comes." (42)

These comments disturbed those on the left of the party such as John Strachey and Cyril Joad, who disliked the comparisons with the Sturmabteilung (SA) used by the Nazi Party in Germany. This information was leaked to the press and he was forced to deny the comparisons with Adolf Hitler: "We are simply organising an active force of our young men supporters to act as stewards. The only methods we shall employ will be English ones. We shall rely on the good old English fist." (43)

Cynthia Mosley also disagreed with her husband's move to the right. According to Robert Skidelsky: "Cimmie (Cynthia) was frankly terrified of where his restlessness would lead him. She hated fascism and Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere, the press baron). She threatened to put a notice in The Times dissociating herself from Mosley's fascist tendencies. They bickered constantly in public, Cimmie emotional and confused, Mosley ponderously logical and heavily sarcastic." (44)

Harold Nicolson was also worried by Mosley's attraction to fascism. "What makes it so distressing is that I should like to be able to encourage and support you in everything you do and feel.... I do not think that in practice you will succeed in keeping distinct the ideology of fascism from the violent and untruthful methods which the fascists have adopted in Italy. I think there may well be a future for the corporate state idea in this country. But I do not think... there is any possible future for direct action: we have, by training and temperament, become possessed of indirect minds." (45)

John Strachey believed that the New Party should develop close contacts with the Soviet Union: "A New Party Government will enter into close economic relations with the Russian Government and will endeavour to conclude such trading contracts between suitable British and Russian statutory organisations as will rapidly develop the controlled interchange of goods between the two countries." When this policy was rejected, Strachey resigned from the party. (46)

In the 1931 General Election the New Party fielded 25 candidates. For health reasons, Cynthia decided not to stand. Oswald Mosley decided to make use of her personal following and stood instead of her at Stoke-on-Trent but he only obtained 10,500 votes and was bottom of the poll. Only two candidates, Mosley and Sellick Davies, standing in Merthyr Tydfil, saved their deposits. The total votes cast for the New Party were 36,377. This compared badly with the Communist Party of Great Britain, which managed 74,824 votes for 26 candidates. Ramsay MacDonald, and his National Government won 556 seats. Mosley told Nicolson that "we have been swept away in a hurricane of sentiment" and that "our time is yet to come". (47)

The British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was formally launched on 1st October, 1932. It originally had only 32 members and included several former members of the New Party: Cynthia Mosley, Robert Forgan, William E. Allen, John Beckett and William Joyce. Mosley told them: "We ask those who join us... to be prepared to sacrifice all, but to do so for no small or unworthy ends. We ask them to dedicate their lives to building in the country a movement of the modern age... In return we can only offer them the deep belief that they are fighting that a great land may live." (48)

Over the next few months a large number of people joined the organisation such as Charles Bentinck Budd, Harold Harmsworth (Lord Rothermere), Major General John Fuller, Wing-Commander Louis Greig, A. K. Chesterton, David Bertram Ogilvy Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale), Unity Mitford, Diana Mitford, Patrick Boyle (8th Earl of Glasgow), Malcolm Campbell and Tommy Moran. Mosley refused to publish the names or numbers of members but the press estimated a maximum number of 35,000. (49)

Mosley decided that members of the BUF should wear a uniform. The black shirt was to be the symbol of fascism. According to Mosley the "black shirt was the outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace". The uniform enabled his stewards to recognise each other in a fight against those trying to disrupt BUF meetings. "In addition, the uniform was a symbol of authority, and as such his uniformed squads would not only be a rallying-point, but also a striking-force in any battle that might develop with the communists for the control of the State." (50)

Oswald Mosley began to argue for national socialism: "How can any international system, whether capitalist or Socialist, advance or even maintain the standard of life of our people? None can deny the truism that to sell we must find customers and, as foreign markets progressively close... the home customer becomes ever more the outlet of industry. But the home customer is simply the British people, on whose purchasing power our industry is ever more dependent. For the most part the purchasing power of the British people depends on the wages and salaries they are paid... Yet wages and salaries of the British people are held down far below the level which modern science, and the potential of production, could justify because their labour is subject to... undercutting competition... on both foreign and home markets.... The result is the tragic paradox of poverty and unemployment amid potential plenty.... Internationalism, in fact, robs the British people of the power to buy the goods that the British people produce." (51)

Cynthia Mosley remained a member of the British Union of Fascists but was not a strong believer in fascism. She was also in bad health. Harold Nicolson wrote: "Cimmie (Cynthia) comes to see me. She has not been well. She faints. She even faints in bed. She talks about Tom (Oswald) and Fascismo. She really does care for the working-classes and loathes all forms of reaction." (52)

Cynthia, the mother of two children (Elisabeth and Nicholas), had a difficult pregnancy with a third child. Nicholson once again wrote about the situation: "Cimmie has been very ill. She has kidney trouble and they want to do a caesarean operation. Unfortunately the child is too young to survive and Climmie wants to hang on for a fortnight. Tom (Oswald) is faced with the awful dilemma of sacrificing his baby or his wife." (53)

Michael Mosley was born on 25th April 1932. After a long convalescence Cynthia's health gradually recovered. In April 1933 she agreed to accompany her husband to visit Benito Mussolini. They all appeared together on the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia, and made the fascist salute in one of the very rare occasions when she publicly showed any sympathy with fascism." (54)

On her return to London she was again taken ill and was rushed to hospital to have her appendix removed. The operation was successful but two days later, on 16th May, 1933, she died of peritonitis. Oswald Mosley was completely shattered by Cynthia's death but according to his friends it intensified his political beliefs and made him even more committed to fascism: "He now regards his movement as a memorial to Cimmie and is prepared willingly to die for it." (55)

Primary Sources

(1) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981)

Cynthia - or Cimmie as she was known to her friends - has come down to us as a somewhat idealised figure. Her undoubted virtues have seemed to shine forth even more strongly by comparison with her husband's failings. Although Cynthia actively supported Mosley in all his undertakings, developing great political courage and considerable platform gifts, she never aroused anything like the bitter feelings he did. Despite her devotion to the workers' cause, she remained a figure of the Establishment, in the well-known tradition of the warm-hearted, emotional person with an instinctive sympathy for the underdog. Her intellectual understanding of socialism was limited, but she made up for this with an automatic revolt against any form of injustice. The gossip columns gushed with conventional phrases about her beauty; but photographs reveal her as handsome rather than beautiful, with prominent teeth, a square chin and a distinct tendency to stoutness She played an important part in Mosley's political success, especially on the human level. Whereas he tended to be remote aril deficient in warmth, often giving people the impression of using them for his own ends, Cynthia was emotional, warm, transparerttly sincere. She disarmed suspicion, added the human touch, smoothed personal relations and, especially later in the Labour Party, came to stand as guarantor for Mosley's own sincerity.

(2) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982)

Cimmie (Cynthia) herself had joined Tom (Oswald) as a member of the Labour Party. The jibes which hitherto had been directed at Tom for his anti-Tory activitin now also began to be directed at her. There were comments in the newspapers about her money: if she and Tom were socialists why did they not give the property away; why did they live in a house with qxtcen rooms; why did Cimmie appear on Labour platforms in jewels and 'costly furs'? To this she and Tom replied that it would not help others in any serious way if they gave away their money and they could be of more use to socialism by themselves using it to finance organisation and propaganda. As for Cimmie's 'jewels' - they had been, in the instance quoted, she explained, bits of glass in a dress bought for a few shillings in India. There was then a peculiar wrangle with the Press on the subject of family titles. Tom was reported as having said he would not use the `Sir' of his baronetcy when his father died; Cimmie as having remarked, rather irrelevantly, that she wanted to drop the `Lady' Cynthia and be known as plain Mrs Mosley but that unfortunately there was no legal way of doing this. Tom summed up: `In any case inside the Labour movement my wife is always known as Comrade Mosley and what she is called outside does not really matter.'

(3) Duncan Sutherland, Cynthia Mosley: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2009)

Throughout their marriage her husband was chronically unfaithful, but Cynthia Mosley followed him loyally through the vicissitudes of his political career, joining the Labour Party with him in 1924... At party gatherings she stood out in her fur stole and jewellery, but the 'diamond dress' for which newspapers criticized her was in fact decorated with glass baubles. She was tall and attractive with dark hair, prominent teeth, and a square chin, and her father felt she looked the most ‘Curzon’ of his daughters, though in later years she became heavier owing to illness and stress, and one contemporary remembered her constantly wearing a sad expression.

Cynthia Mosley did not really understand socialism but had a long-standing sympathy for the underdog. In parliament she spoke on women's unemployment and widows' pensions, and in her memorable maiden speech she reversed the Conservative charge that unemployment insurance would 'demoralize' recipients....

Throughout their careers Cimmie's warmth and sincerity made her more popular and better trusted than her husband, but after he resigned ostentatiously from the Labour government in May 1930 she soon made the "heart-breaking" decision to follow him out of the party. Despite the protests of her constituency association, many in the party still liked her and sympathized as she stood stoically by her mercurial and often cruel husband...

She campaigned for her husband's New Party, but health considerations and political disillusionment prompted her not to seek re-election. After the party fared poorly in the 1931 election - Oswald came in last place when he stood for Cynthia's Stoke-on-Trent constituency - the New Party became in 1932 the British Union of Fascists (BUF). The violent struggle which he now believed was necessary was abhorrent to her gentle nature, and she threatened to distance herself from the BUF with a newspaper advertisement. But typically she remained publicly loyal, joining him and Mussolini at a fascist parade in Rome and investigating possible designs for a British fascist flag...

Her post-political life was increasingly lonely as her husband spent more time on his new cause and with his future wife, Diana Guinness. After an appendix operation she contracted peritonitis and died at 3 Wilbraham Place, London, on 16 May 1933. The leaders of all parties supported the construction of a memorial day-nursery in Kennington, and she was buried the following year in a tomb designed by Lutyens at Savehay Farm.

Despite the advantages which Cynthia Mosley brought her husband, it is difficult to consider her career as anything but an adjunct to his, and in some ways she was a victim of it. One colleague wrote that she was 'sacrificed to her husband's hurried ambitions' (Hamilton, 181), and she was probably better suited to home and society than to politics. She made little impact in parliament, where her artless speaking style contrasted with her father's, and her own conclusion was that the Commons was futile and a waste of time; among women MPs she is unique if only for subsequently rejecting parliamentarianism. In May 1931 she told readers of the Daily Sketch of her daunting thought that in parliament 'it does not really matter what you say, that it will have no effect on anyone at all, and that you might as well not say it' (N. Mosley, 204). When taunted in parliament that July about her six months' absence, her riposte was to say that 'going round the country … to rouse people to the incompetence of the Labour Government … is more important than sitting here' (Hansard 5C, 15 July 1931, col. 674). Her post-political life was increasingly lonely as her husband spent more time on his new cause and with his future wife, Diana Guinness. After an appendix operation she contracted peritonitis and died at 3 Wilbraham Place, London, on 16 May 1933. The leaders of all parties supported the construction of a memorial day-nursery in Kennington, and she was buried the following year in a tomb designed by Lutyens at Savehay Farm.

Student Activities

References

(1) Anne de Courcy, The Viceroy's Daughters: The Lives of the Curzon Sisters (2001) page 21

(2) Duncan Sutherland, Cynthia Mosley: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2009)

(3) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982) page 19

(4) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 84

(5) George Curzon, diary entry (21st March, 1920)

(6) George Curzon, diary entry (22nd March, 1920)

(7) Robert Skidelsky, Oswald Mosley: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2012)

(8) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982) page 25

(9) Frederick W. Craig, British General Election Manifestos, 1900-1966 (1970) pages 9-17

(10) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) pages 120-125

(11) Margot Asquith, letter to Oswald Mosley (7th April 1924) (10)

(12) Pamela Brookes, Women at Westminster: An Account of women in the British Parliament (1967) page 80

(13) Duncan Sutherland, Cynthia Mosley: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2009)

(14) Beatrice Webb, diary entry (8th June, 1923)

(15) Westminster Gazette (17th December, 1926)

(16) The Daily Express (8th December, 1926)

(17) The Morning Post (7th December, 1926)

(18) Oswald Mosley, speech at Smethwick (4th December, 1926)

(19) Sir Oswald Mosley Snr., letter to the The Daily Mail (12th April, 1926)

(20) Sir Oswald Mosley Snr., interviewed in the The Daily Express (13th December, 1926)

(21) The Morning Post (21st December, 1926)

(22) Oswald Mosley, speech at Smethwick (21st December, 1926)

(23) Stuart Ball, Stanley Baldwin : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(24) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 159

(25) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982) pages 117-118

(26) Duncan Sutherland, Cynthia Mosley: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2009)

(27) Cynthia Mosley, speech in the House of Commons (31st October, 1929)

(28) David Marquand, Ramsay MacDonald (1977) page 539

(29) Edmund Dell, A Strange Eventful History: Democratic Socialism in Britain (1999) page 35

(30) Ramsay MacDonald, letter to Walton Newbold (2nd June, 1930)

(31) Philip Snowden Report (1st May, 1930)

(32) Ramsay MacDonald, diary entry (19th May, 1930)

(33) Hugh Dalton, quoting Clement Attlee, in his diary (20th November, 1930)

(34) John Bew, Citizen Clem: A Biography of Attlee (2016) page 149

(35) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2010) page 212

(36) Oswald Mosley, My Life (1968) page 233

(37) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 243

(38) Robert Benewick, The Fascist Movement in Britain (1972) pages 66-67

(39) Ramsay MacDonald, letter to Cynthia Mosley (5th March, 1931)

(40) Nicholas Mosley, Rules of the Game: Sir Oswald and Lady Cynthia Mosley 1896-1933 (1982) page 173

(41) Martin Pugh, Hurrah for the Blackshirts (2006) page 120

(42) Oswald Mosley, speech at New Party committee meeting (14th May 1931)

(43) The Manchester Guardian (16th May 1931)

(44) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 284

(45) Harold Nicolson, letter to Oswald Mosley (20th May, 1932)

(46) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 260

(47) Stephen Dorril, Black Shirt: Sir Oswald Mosley and British Fascism (2006) pages 187-188

(48) Oswald Mosley, speech (1st October, 1932)

(49) Robert Benewick, The Fascist Movement in Britain (1972) page 110

(50) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 292

(51) Oswald Mosley, Tomorrow We Live (1938) pages 28-30

(52) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (13th January, 1932)

(53) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (8th March, 1932)

(54) Robert Skidelsky, Mosley (1981) page 297

(55) Harold Nicolson, diary entry (11th January, 1933)

John Simkin