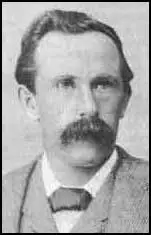

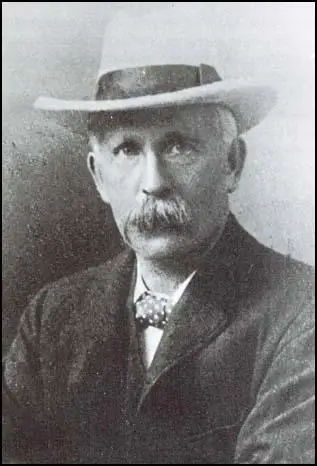

Arnold Hills

Arnold Hills was born on the 12th March, 1857. He was educated at Harrow and played for the school's football and cricket teams. Hills was a talented footballer and represented Oxford against Cambridge in the varsity match.

Hills was also good at other sports and was the A.A.A. one-mile champion while at university. Hills also played for Oxford University in the F.A. Cup Final in 1877. Unfortunately he was on the losing side with the Wanderers winning the game 2-1. An inside-right, Hills was for many years a member of the Old Harrovians and in 1879 won an international cap playing for England against Scotland. A game that England won 5-4.

In 1880 Hills joined the board of his father's company, Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding. He initially lived in the East India Dock Road in Canning Town. He became concerned about the living conditions of the local people. Hills commented that "the lack of recreational facilities was one of the worst deprivations in the lives of West Ham residents". He added "the perpetual difficulty of West Ham is its poverty, it is rich only in its population."

Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding occupied 30 acres of land at West Ham on the Essex side of Bow Creek and was London's last surviving major shipbuilding firm.In 1860 it had employed 6,000 men, but by 1895 it was half that number, and was suffering from serious competition from companies based on the River Clyde and in the North East of England.

Hills moved out of his house in Canning Town when he married Mary Elizabeth Lafone in 1886. Over the next few years she gave birth to one son and four daughters. On the death of his father, Hills became the managing director of the Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding Company.

In 1888 Hills became President of the London Vegetarian Society. He also served as President of a London Vegetarian Rambling Club and founded the magazine, The Vegetarian. Hills was also an active member of the Temperance Society.

In 1889 Ben Tillett, General Secretary of the Tea Operatives & General Labourers' Association, organized a strike over pay and conditions. The men who worked at the London Docks demanded four hours continuous work at a time and a minimum rate of sixpence an hour. After the successful strike, the dockers formed a new General Labourers' Union. Tillett was elected General Secretary and Tom Mann became the union's first President. In London alone, 20,000 men joined this new union. This included workers at the Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding company. Joiners and engineers at the company took part in strikes in 1890 and 1891. Hills created a great deal of bad feeling by sacking these workers and employing "scab" labour.

Hills established the Thames Ironworks Gazette in 1895. It was a combination between a local newspaper, popular history magazine and company newsletter. On 29th June, 1895, Hills announced in his newspaper that he intended to establish a football club. The information appeared under the headline: "The importance of co-operation between workers and management". He referred to the industrial dispute that had just taken place and insisted he wanted to "wipe away the bitterness left by the recent strike". Hills added: "Thank God this midsummer madness is passed and gone; inequities and anomalies have been done away with and now, under the Good Fellowship system and Profit Sharing Scheme, every worker knows that his individual and social rights are absolutely secured."

The article asked workers interested in joining the Thames Iron Works Football Club to contact Francis Payne, a senior clerk at the company. Charlie Dove, an apprentice riveter with the Thames Iron Works, was one of those who paid an annual subscription of 2/6 (12.5p) to join the club. He was joined by about fifty other colleagues in this new venture. Training took place on Tuesday and Thursday nights in a gas-lit schoolroom at Trinity Church School in Barking Road. Training mainly consisted of Army physical training exercises. They also went for runs along the Turnpike Road (Beckton Road).

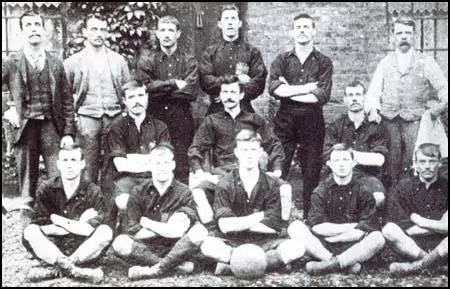

Other employees who played in the team included Thomas Freeman (ships fireman), Johnny Stewart (boilermaker), Walter Parks (clerk), Walter Tranter (boilermaker) James Lindsay (boilermaker), William Chapman, George Sage, and William Chamberlain.

Standing next to him is Francis Payne the club secretary.

The club was financed by members' subscriptions and a generous contribution from the Thames Iron Works. It was run by a club committee made up of "clerks, foreman or supervisors at the Ironworks". As over 50 men had joined the club, it was necessary to find enough matches for two teams.

Home games took place at Hermit Road, Canning Town. It had previously been used by Old Castle Swifts, a company club sponsored by Donald Currie, the owner of the Castle Shipping Line. Old Castle Swifts had been the first professional football club in Essex but it went out of business at the end of the 1894-1895 season.

Francis Payne was appointed as club secretary. The local newspaper praised Arnold Hills for forming a football team: "If this example were only followed by other large employers, it would lead to much good feeling."

Robert Stevenson became captain of the team. He was the Thames Ironworks most experienced footballer and had previously played for Woolwich Arsenal. Other players included John Woods, who also played cricket for Essex and George Gresham, who had been a regular scorer with Gainsborough Trinity. However, the star player was the 17 year old William Barnes..

(left to right): Arnold Hills, French, Graham, Francis Payne, John Woods, William Hickman

and Tom Robinson (trainer). Centre; William Chamberlain, George Sage, Robert Stevenson,

William Chapman, William Barnes. Front; Johnny Stewart, Thomas Freeman.

Thames Iron Works pioneered floodlit football. The pitch was surrounded by light bulbs attached to poles. The football was dipped in pails of whitewash to make it easier to see. The first night match took place on 16th December, 1895. It was later reported that "the occasion was a success". It went onto the say that the generator "met the requirements and worked well" and "ten lights each of 2,000 candle power gave a good view to those present".

Their fourth floodlit game was against Barking Woodville. In his book, Iron in the Blood, John Powles quotes a report in the West Ham Herald: "Boys were swarming up over the fences for a free view when I put in an appearance. And what a smart man the Ironworkers have at the gate. He seemed to think my ticket was a real fraud until he had turned it upside down and inside out, and smelled at it for a considerable time. But he graciously passed me at last." The Irons won 6-2 with Charlie Dove getting a hat-trick.

On 20th March, 1896, Thames Iron Works played a night game against the famous West Bromwich Albion. The club committee arranged for the erection of canvas screens round the moat-ringed pitch, and charged the public for watching the game. WBA won 4-2.

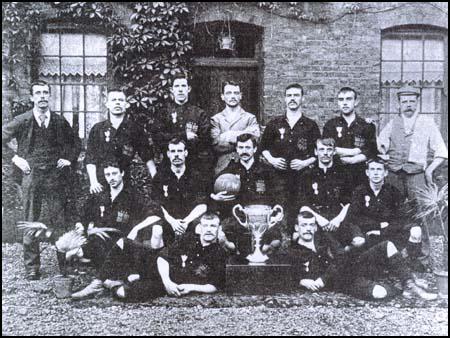

By the end of the season the Thames Iron Works had won 30 of its 46 games. The team also defeated Barking to win the West Ham Charity Cup. The 17 year old, William Barnes, scored the only goal in the deciding game.

Hills continued to take a close interest in the fortunes of the club. In 1896 he sent a message to every member of the team: "As an old footballer myself, I would say, get into good condition at the beginning of the season, keep on the ball, play an unselfish game, pay heed to your captain, and whatever the fortunes of the first half of the game, never despair of winning, and never give up doing your very best to the last minute of the match. That is the way to play football, and better still, that is the way to make yourselves men."

Soon after the start of the 1896-97 season Thames Iron Works were evicted from the Hermit Road ground for violating their terms of tenancy by erecting a perimeter fence and charging admission to matches. Arnold Hills arranged to lease a piece of land in Browning Road in East Ham. This was only a temporary measure and after purchasing land at Canning Town, Hills built what became known as the Memorial Grounds. It cost £20,000 to build and was considered to be one of the best stadiums in the country. Hills claimed it could hold 133,000 spectators and applied to hold an FA Cup Final at the Memorial Grounds. This only allowed 16 inches for each person and the Football Association turned the idea down.

s well as a football arena, it also had a cinder running track, tennis courts and an outdoor swimming pool. According to one report, the 100 feet (30.4m) long pool was the largest in England. The Memorial Grounds was opened in June, 1897.

Hills used to organize a New Year party for the children of his employees. For example, this is how a local paper reported the party that brought in 1898. "Professor Anderson gave a few conjuring tricks and the young people were much amused by the comical actions of some of the Thames Ironworks Minstrels. Mr Hills gave a short address, and after nearly two hours had been spent in an enjoyable manner the children were marched out of the hall, each receiving a bun and an orange." The newspaper also reported that members of the Thames Ironworks football team were in attendance.

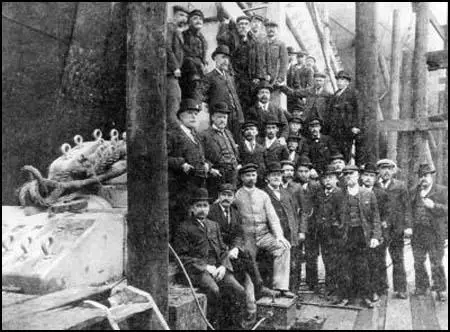

On 21st June, 1898, a 6,000 ton warship Albion became the first ship to be launched by a member of the royal family at the Thames Iron Works and Shipbuilding Company. The Duke of York, the future George V, and his wife, arrived for the launching ceremony in the early afternoon. Around 30,000 local people also competed to get a good view of this historic event. Over 200 people stood on a workmen's slipway alongside the uncompleted warship. At 2.50 pm the Duchess of York broke a bottle of champagne over the hull of the Albion. The ship entered the water faster than intended. This caused a massive backlash of water like a tidal wave that knocked people standing on the workmen's slipway into Bow Creek.

A total of 38 people died in the accident. This included a brother and sister, Ernest and Kittie Hopkins. Probably the saddest case was of Isabel White. When her body was recovered, her children, Lottie 5, and Queenie 2, were still clinging to her frock.

Arnold Hills was devastated by the accident and arranged to pay all the bereaved families' funeral expenses and personality visited the homes of the victims. Although the coroner criticized the organization of the launch (he recommended that in future accommodation should be provided by specially erected stands) Hills that he "met with no shadow of bitterness, no tone of complaint".

Soon afterwards two other terrible accidents had an impact on the people who lived in the area. An explosion onboard the Manitoba moored in the Albert Dock killed five workmen. This was followed by the loss of the 7,000 ton liner Mohegan on the Cornish coast. An amazing 34 members of the crew who died in the accident lived in West Ham.

It was hoped that the new 1898-1899 season would help take the workers' minds off these terrible events. That season Hills reluctantly accepted the proposal of Francis Payne that the club should recruit some professional players. Although a strong supporter of amateur football he argued it was "necessary to introduce a little ferment of professional experience to leaven the heavy lump". Payne's main argument was that better players would attract larger crowds. With attendances averaging 2,000, the club was being run at a loss and Hills was constantly being asked to subsidize the venture.

Thames Iron Works easily won the Southern League Division 2 in the 1898-1899 season. They obtained 9 points more than their nearest rivals Wolverton and Watford, who tied for second place. Outstanding performers that season included Charlie Dove, Tommy Dunn, Tommy Moore, Henry Hird, George Gresham, Walter Tranter, Jimmy Reid and Roderick McEachrane. The main star was David Lloyd who scored 12 goals in only 11 league appearances.

Arnold Hills, raised doubts about the wisdom of employing highly paid professionals. At the end of the season he wrote: "The committees of several of our clubs, eager for immediate success, are inclined to reinforce their ranks with mercenaries. In our bands and in our football clubs, I find an increasing number of professionals who do not belong to our community but are paid to represent us in their several capacities... Now this is a very simple and effective method of producing popular triumphs. It is only a matter of how we are willing to pay and the weight of our purses can be made the measure of our glory. I have however, not the smallest intention of entering upon a competition of this kind: I desire that our clubs should be spontaneous and cultivated expressions of our internal activity."

In 1899 Francis Payne, the club secretary, was given the task of finding good players for Thames Iron Works first season in the top division of the Southern League. According to one report, Arnold Hills, gave Payne £1,000 to find the best players available.

Payne employed an agent and former professional footballer named Charles Bunyan to obtain a player based in Birmingham. Bunyan missed his appointment with the player targeted by Payne. He then approached another player he thought might be interested in joining the club. However, this player reported Bunyan to the Football Association. The FA held an investigation into the matter and as a result, Bunyan was suspended for two years. Payne was also suspended and the Thames Iron Works was fined £25. George Neil, who had previously played for the Thames Iron Works, became the new secretary/manager.

In 1900 Arnold Hills decided to expand his business interests by acquiring the engineering firm of John Penn & sons. In order to raise new capital to finance the takeover, he decided to make Thames Iron Works a public company. This meant that in future he would be accountable to shareholders. Hills was no longer in a position where he would be allowed to pump company money into the football club.

As a result of this move, the football club was also reorganized. Thames Iron Works FC became West Ham United FC. Lew Bowen, a clerk at the Iron Works, became the new club secretary. Attendances at games, compared to their close rivals, remained disappointing. One reason for this was no nearby railway station. West Ham began to verge on the edge of bankruptcy and by the end of the 1903-04 season the club only had had the money to pay the wages of one professional player, Tommy Allison, during the summer.

Arnold Hills was also having financial problems and was unwilling to re-negotiate a rental agreement to use the Memorial Grounds that was acceptable to West Ham United. The club was forced to find another sponsor. A local brewery agreed to advance them a loan to help them purchase a new ground. A deal was arranged with the Catholic Ecclesiastical Authorities but the Home Office made it clear that they did not approve of the land being used by West Ham United. Syd King went to see Sir Ernest Gray, an influential Member of Parliament. As King later explained, "through his good offices, subject to certain conditions, we were finally allowed to take possession of Boleyn Castle".

In early 1900 Arnold Hills decided to expand his business interests by acquiring the engineering firm of John Penn & sons. In order to raise new capital to finance the takeover, he decided to make Thames Iron Works a public company. This meant that in future he would be accountable to shareholders. Hills was no longer in a position where he would be allowed to pump company money into the football club.

On 7th March, 1900, the West Ham Guardian reported that: "It is announced that the committee of Thames Ironworks FC are to consider some sort reorganization. A proposal is evidently on the table. For one who has it on authority says it will 'if adopted, undoubtedly be to the club's advantage'. This is good news. Supporters are tired of seeing the club so low down as fourth from the bottom".

A few weeks later the West Ham Guardian reported that the football would be sold. "With regard to next season however, a meeting will be called, and the Mayor of West Ham will be asked to preside, at which gathering the locals will be asked to take up 500 £1 shares. If this amount be raised Mr A. F. Hills will add to it another £500, and, in addition, grant the use of the Memorial Grounds. Another condition is that all members of the team must be teetotallers. It is probable too, that the name of the club will be changed to Canning Town." The newspaper was wrong about this and the new club was called West Ham United. The idea that all players should be teetotallers was also dropped.

It was hoped that over 2,000 supporters would buy shares in the new club. The West Ham Guardian urged local people to buy shares: "There is little question that the present question of managing small teams is not the right one. For so many clubs get into debt and finally are snuffed out... A shareholder will have everything to gain, by attending the matches, and inducing others to come with him, therefore it seems to me that the nail has been hit right on the head, and the problem of the football world of management is about to be solved."

Hills announced that anyone who purchased just ten shares would be allowed to join the Board of Directors of the club. Despite this offer, a large number of shares remained unsold and the the finances of the new club remained in a poor state. had trouble selling these shares to supporters.

In September, 1900, The Morning Leader reported: "The prospectus of the new limited liability company, to be known under the title of the West Ham Football Club Company Limited is at hand. The primary object will be to encourage and promote the game of football in West Ham and district, and powers have also been taken by the company authorising them at any time to acquire land and other property."

It was also announced that: "The directors propose to make the following charges, to shareholders only, for season-tickets for the football season 1900/01: admission to ground and open stand, 7s 6d, admission to ground, enclosure and grand stand 10s 6d and 12s 6d respectively.... Mr. A. F. Hills who will most likely to take up £500 worth of shares, is very keen on playing a teetotal eleven next season, and the experiment is worth trying if only to vindicate the rights of football employers to call their own tune after paying the piper."

The capital of West Ham United was £2,000 (4,000 shares at 10s each). Arnold Hills purchased 1,000 shares and remained the major influence at the club. However, he was unable to enforce the idea that all players should be teetotallers.

Hills now concentrated on the Thames Iron Works & Shipbuilding Company. Unfortunately, the business went into decline and between 1904 and 1910, the company only received only £1 million of work from the Admiralty. However, the following year, the Thames Iron Works built the world's largest battleship, HMS Thunderer. Hills complained that most of the new orders were going to the northern shipyards of the Tyne and Clyde.

Hills became very ill and developed a wasting disease which left him almost totally paralysed. On 1st January, 1912, Hills attended a protest meeting in Trafalgar Square before visiting the offices of Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty. Hills was carried in on a stretcher and the Daily Mail described him as the "invalid builder of Dreadnoughts".

The Thames Iron Works, the last great shipbuilder on the Thames, was closed down on 21st December, 1912. Although he remained in poor health, Hills did live to see West Ham United play against Bolton Wanderers in the F.A. Cup Final in 1923.

Arnold Hills died at his home "Hammerfield" in Penshurst on 7th March, 1927.

Primary Sources

(1) Arnold Hills, statement (September, 1896)

As an old footballer myself, I would say, get into good condition at the beginning of the season, keep on the ball, play an unselfish game, pay heed to your captain, and whatever the fortunes of the first half of the game, never despair of winning, and never give up doing your very best to the last minute of the match. That is the way to play football, and better still, that is the way to make yourselves men.

(2) Arnold Hills, statement (May, 1899)

The committees of several of our clubs, eager for immediate success, are inclined to reinforce their ranks with mercenaries. In our bands and in our football clubs, I find an increasing number of professionals who do not belong to our community but are paid to represent us in their several capacities... Now this is a very simple and effective method of producing popular triumphs. It is only a matter of how we are willing to pay and the weight of our purses can be made the measure of our glory. I have however, not the smallest intention of entering upon a competition of this kind: I desire that our clubs should be spontaneous and cultivated expressions of our internal activity."

(3) Brian Belton, Founded on Iron: Thames Ironworks and the Origins of West Ham United (2003)

Hills was not the first capitalist in the London area to seek to ingratiate himself with his workers using company benefits and the carrot of better employment conditions. When the workers of the South Metropolitan Gas Company "left work" in 1889 (strikes were illegal at that time) in protest against the company's profit-sharing plans, owner George Livesey extended the scheme, making a huge investment in social facilities. Opposite the present Port Greenwich/English Partnership offices stood the company's institute and theatre: both were built as part of a co-partnership initiative. This extended to a scheme that provided children born to employees with work, housing and burial at the expense of the company.

As will be seen later, the Hills fanlilv had a close association with the gas industry and were always quick to learn and benefit front it - Arnold, in this respect, was carrying on a tradition. He was a man of his era and true to the tactics of his class, but he was also part of a group of industrialists ahead of their time. Not until the 1960s did the majority of large-scale organisations in the USA and later Japan begin to rediscover the full business benefits in developing paternalistic and philanthropic relationships between themselves and their employees.

All this should not undermine the fact that Hills was certainly passionate and sincere in his hope that the worker associations and other company initiatives would positively effect worker morale and foster employment satisfaction within the Ironworks. His initiatives were not straightforward, cynical efforts to exploit his workers. His beliefs, aesthetic outlook and moral convictions, including a wish to "better" those in his employ and his faith in the enterprise of Thames Ironworks as a philanthropic community, were deeply set. He was a man steeped in the Protestant work ethic. The making of money was considered a vulgar enterprise for a gentleman, although, in contradiction to this outlook, to be a respectable member of upper class society one certainly needed to command appreciable financial resources.