On this day on 25th December

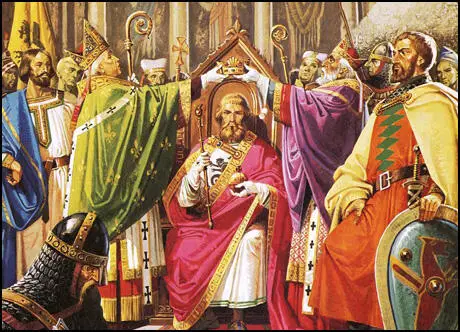

On Christmas Day in 1066, William the Conqueror was crowned king of England at Westminster Abbey. After his coronation, William the Conqueror claimed that all the land in England now belonged to him. William retained about a fifth of this land for his own use. Another 25% went to the Church. The rest were given to 170 tenants-in-chief (or barons), who had helped him defeat Harold at the Battle of Hastings. These barons had to provide armed men on horseback for military service. The number of knights a baron had to provide depended on the amount of land he had been given.

When William granted land to a baron an important ceremony took place. The baron knelt before the king and said: "I become your man." He then placed his hand on the Bible and promised to remain faithful for the rest of his life. The baron would then carry out similar ceremonies with his knights. By the time William and his barons had finished distributing land there were about 6,000 manors in England. Manors varied in size, some having only one village, while others had several villages within its territory.

On Christmas Day in 1634 Lettice Knollys died. Lettice, the eldest of the sixteen children of Sir Francis Knollys and Katherine Carey, was born at Rotherfield Greys, near Henley-on-Thames, on 8th November, 1543. Her grandmother was Mary Boleyn, a mistress of Henry VIII.

Her father was a member of the House of Commons and and important figure in promoting legislation favoured by the royal family. (2) He was also Master of the Horse to Prince Edward and as a child she got to know members of the royal family. The post also paid well and came with a salary of £1,500 per annum.

Sir Francis Knollys was a strong Protestant and during the reign of Mary he went into exile. However, after Elizabeth obtained power Knollys was appointed vice-chamberlain, and Lettice became one of the Queen's ladies-in-waiting. It has been claimed that Lettice "was a beautiful woman in the dark sullen fashion that can infuriate men with desire - and women with jealousy... and she flaunted her beauty shamelessly."

In 1560 Lettice Knollys married Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex. Over the next four years she gave birth to Penelope (1563) and Dorothy (1564). In 1565, the Spanish ambassador, Diego Guzmán de Silva, reported that Lettice had become romantically linked with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. He described her as one of the best-looking women in England but believed that Dudley's attentions was intended to persuade Elizabeth to marry him. This failed but it did develop in Elizabeth a strong hostility to Lettice.

Robert Devereux was born in 1566. It has been claimed that Robert's father was really the Earl of Leicester. It has also been suggested that Elizabeth was his real mother. Most historian's reject this theory and as Philippa Jones, the author of Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010) has pointed out: "At this time Elizabeth... headed a household of more than 1,000 people and rarely had any time to herself. She was constantly observed by the officials of her Court, who were desperate to stay abreast of events, as well as by the spies and representatives of various foreign powers. Logistically, how viable was it for the Queen to find sufficient time alone with a lover, hide any signs of a pregnancy for a long nine months and then have a secret labour and birth." In October 1569, Lettice gave birth to a second son, Walter. Robert Lacey, points out: "It was a well-balanced Tudor family: two daughters to bestow in marriage: two sons to double up against the risks of sixteenth-century illness and medicine."

Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex, died of dysentery in September 1576 while on military service in Ireland. It was claimed that he had been poisoned on the orders of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, because of his adulterous relationship with Devereux's wife. A post-mortem examination ordered by Sir Henry Sidney, revealed that he had died of natural causes.

Robert Devereux now inherited the earldom and the family estates from his father. By virtue of succeeding to his title as a minor, Essex became a ward of the crown. He was taken by William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the lord treasurer and master of the Court of Wards. According to a report of November 1576, the ten-year-old Devereux "can express his mind in Latin and French as well as English" and as well as being "very curious and modest" was more "disposed to hear than to answer" and was "greatly to learning".

Robert was brought up with Burghley's older son, Robert Cecil. The historian Anka Muhlstein has argued "The two youngsters, so dissimilar in their tastes and talents, had never been close, but William Cecil's affection for Essex and the later's respect for the old man were never disputed."

By September 1578, two years after her husband's death, Lettice Knollys was unmistakably pregnant. Sir Francis Knollys was furious and had a meeting with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the man responsible for her condition. On 21st September, Knollys arranged for a brief marriage service to take place. All those involved were sworn to secrecy but thirteen months later, one of Dudley's enemies, told Queen Elizabeth about the marriage.

Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) has commented: "Elizabeth's rage was shattering. That she had repeatedly refused to marry Leicester herself was, as anyone would foresee, a straw against the torrential force of wounded affection, betrayed confidence, jealously and anger." At first she considered sending him to the Tower of London but she eventually banished him to his house in Wanstead and Lettice was exiled from court for ever.

Lettice Dudley gave birth to Robert Dudley (Lord Denbigh) in June 1581. Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester now acknowledged his new son as his new heir. The three-year-old Robert died suddenly on 19th July 1584. His death destroyed the dynastical hopes of the House of Dudley.

In 1585 the Earl of Leicester was given command of the army going to the Netherlands. It was agreed that Lettice's son, Robert Devereux, should accompany his step-father to war and he sailed with Leicester's entourage from Harwich on 8th December. A month later, when the army was mustered for service, the 19-year-old Devereux was appointed colonel-general of the cavalry. Command of the cavalry was not only socially prestigious but also politically significant and it appeared that Leicester was using his power to promote Devereux's career. In September 1586 Devereux participated in Leicester's capture of Doesburg and in the famous skirmish at Zutphen, where he and a small body of other horsemen repeatedly charged a much larger Spanish force with almost foolhardy bravery.

On his return to England, Robert Dudley, now back in favour, arranged for his stepson to meet Queen Elizabeth. It is believed he was hoping his advancement would weaken the position of his main rival, Sir Walter Raleigh. Elizabeth was greatly impressed with Devereux. It has been claimed that "captivated within a few weeks by his gaiety, wit and high spirits, she became besotted with him" and "they were soon inseparable". One of his servants recorded that "nobody near her but my Lord of Essex, and at night my Lord is at cards or one game or another with her, that he cometh not to his own lodging till the birds sing in the morning."

The Queen, who was now in her early fifties, demanded his constant attendance and "would dance with no one else" and insisted he went hunting with her. "Elizabeth's dislike of retiring to bed before dawn exhausted her entourage, but the young earl tirelessly kept her company. After an evening at the theatre they would return to the palace and play interminable hands of cards."

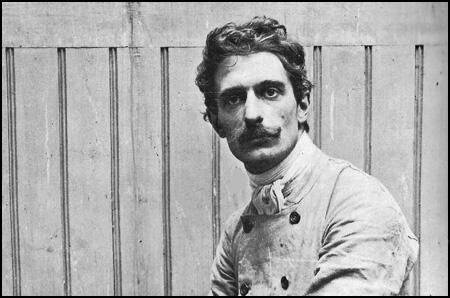

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, was described as being "tall, strikingly attractive with dark eyes and auburn hair" who was "intelligent, witty and flirtatious". It was suggested that the twenty-one-year-old's youth "enlivened her and gave her new energy". At court entertainments he would always sit close to Queen Elizabeth and she was often reported to whisper to him or touch him fondly. Despite the thirty-three age gap, members of the Royal Court began to speculate on the nature of their relationship.

In June 1587, Essex was given the post of Master of the Horse. This made him the only man in England officially allowed to touch the Queen, as he was responsible for helping Elizabeth mount and dismount when she went horse-riding. The post also paid well and came with a salary of £1,500 per annum.

Lettice Knollys used her son's relationship to try and get close to Queen Elizabeth again. However, it was not long before the two women were in conflict. "When Lettice then deliberately started wearing in the royal presence dresses that were finer than the Queen's own garments, Elizabeth exploded." Elizabeth told Lettice "that as but one sun lighted the east, so she would have but one Queen in England". Once again she was told never to return to Court again."

Dudley was a strong supporter of Protestantism. In 1585 he was appointed commander of the expeditionary force to help the Dutch against Spain. Dudley was seen as a "new messiah" and a leader of the international Protestant cause. He was offered the post of Governor General of the Netherlands. He accepted the title, much to the "queen's fury and consternation". When at the beginning of 1586, he was confirmed as absolute governor, "she became incandescent with rage".

Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, died from a malarial infection on 4th September, 1588. It was said that the Queen was so upset that she retired to her chamber and did not appear for two days and eventually William Cecil ordered her door to be broken down.

Lettice was nominally a very wealthy widow. Her combined jointures from Essex and Leicester gave her an income of £3,000 a year, and she possessed £6,000 worth of plate and household furniture. However, Leicester was deeply in debt. He owed Elizabeth over £25,000 and admitted in his will: "I have always lived above any living I had, for which I am heartily sorry". Elizabeth insisted on a public auction of his goods to meet his debts as she had no intention of allowing Lettice to enjoy more of her inheritance than she was entitled to.

In July 1589 the countess suddenly married Sir Christopher Blount, a Roman Catholic, who was the Earl of Leicester's Gentleman of the Horse. It was very unusual for someone of her class to marry a former servant. He was also 12 years her junior. Her son, Walter Devereux, described the marriage as a "unhappy choice". One rumour suggested that Lettice was having an affair with Blount since 1587 and that the couple had murdered Leicester.

Queen Elizabeth decided to send Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, to Ireland. On 27th March, 1599, he set off with an army of 16,000 men. He originally intended to attack the Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, in the north, both by sea and by land. On his arrival in Dublin he decided he needed more ships and horses to do this. Information he received suggested he was significantly outnumbered. Essex also feared that Spain would send soldiers to support the 20,000 Irishmen in Tyrone's army.

Essex decided to launch an expedition against Munster and Limerick. Although this did not bring a great deal of success he knighted several of his officers. This upset the Queen as only she had the power to confer knighthoods. (31) This lasted two months and upset Queen Elizabeth who demanded that Essex confronted Tyrone's army. She pointed out that such a large army was costing her £1,000 a day.

Essex insisted he could not do this until more men from England arrived. He also began to worry that his enemies were keeping him short of supplies on purpose: "I am not ignorant what are the disadvantages of absence - the opportunities of practising enemies when they are neither encountered nor overlooked." As a result of military action and especially illness, Essex now only had 4,000 fit men.

Essex reluctantly marched his men north. The two armies faced each other at a ford on the River Lagan. Essex, aware he was in danger of experiencing an heavy defeat, agreed to secret negotiations. (35) The two men announced a truce but it was not known at the what was said during these talks. Essex's enemies back in London began spreading rumours that he was guilty of treachery. It later emerged that Essex had offered without permission, Home Rule for Ireland.

Queen Elizabeth reacted to this news by appointing Robert Cecil to become master of the Court of Wards, a lucrative post that Essex himself had hoped to occupy. Essex wrote to the Queen that "from England I have received nothing but discomfort and soul's wounds" and that "Your Majesty's favour is diverted from me and that already you do bode ill both to me and to it?"

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, decided to return to England so he could give Queen Elizabeth a detailed account of the agreements reached with the Earl of Tyrone. He brought with him 200 men and six officers. (38) Deserting his post without permission was an extremely grave step. As Anka Muhlstein has pointed out: "His panic and desperation were such that they blinded him to reality. One question remains: Was he going to court to beg the queen to forgive him, or to intimidate her?"

Without stopping at Essex House to change his spoiled, mud-splattered clothes, he crossed the Thames at Westminster by the horse-ferry, and after landing at Lambeth he rode on to Nonsuch Palace at Stoneleigh. On arriving he walked unannounced into Elizabeth's Bedchamber. The Queen had just a simple robe over her nightdress, her wrinkled skin was free of cosmetics and without her wig Essex saw her bald head with just wisps of thinning grey hair "hanging about her ears". This was the reality of the Queen's natural body that no one, except her trusted servants, saw.

Although no man had ever entered her Bedchamber uninvited, the Queen remained calm, not knowing whether or not she was in danger, fearing that he might be leading an attempted coup. Elizabeth refused to talk to him and said she would arrange a meeting with the Privy Council the following day. Messengers were immediately dispatched to London and later that day senior officials arrived with news that their were no signs of an uprising.

Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, was now arrested and interrogated. He was accused of committing a series of offences. The councillors accused him of disobeying the Queen's direct orders and deserting his command in Ireland. They also complained about entering the Queen's Bedchamber without permission. Essex was criticized for knighting dozens of his junior officers without authority. This charge was especially serious. He was accused of trying to create a following composed of men entirely devoted to his service. Essex was held in custody in York House on the Strand and forbidden to leave or receive visitors.

Essex's sister, Lady Penelope Rich, presented Queen Elizabeth with a strongly worded letter. In it she defended her brother, denounced his enemies and complained that Essex had not been allowed enough time to answer his critics. Elizabeth was outraged at Lady Penelope's letter and complained to Robert Cecil about her "stomach and presumption" and ordered her not to leave her house. Soon afterwards copies of the letter was being sold on the streets of London. Lettice Knollys, left her country estate to come to London to petition for her son's release. Elizabeth, who had never forgiven Lettice for marrying Robert Dudley, immediately rejected this plea.

Essex's health was given cause of concern. On 18th December 1599, it appeared he was on the verge of death. This prompted several churches in London to ring their bells or offer special prayers for him. This upset Queen Elizabeth and her Privy Council as he highlighted the fact that Essex remained a popular figure in England.

Essex gradually recovered and on 7th February, 1560, he was visited by a delegation from the Privy Council and was accused of holding unlawful assemblies and fortifying his house. Fearing arrest and execution he placed the delegation under armed guard in his library and the following day set off with a group of two hundred well-armed friends and followers, entered the city. Essex urged the people of London to join with him against the forces that threatened the Queen and the country. This included Robert Cecil and Walter Raleigh. He claimed that his enemies were going to murder him and the "crown of England" was going to be sold to Spain.

At Ludgate Hill his band of men, that included Lettice's husband, Sir Christopher Blount, were met by a company of soldiers. As his followers scattered, several men were killed and Blount was seriously wounded. Essex and about 50 men managed to escape but when he tried to return to Essex House he found it surrounded by the Queen's soldiers. Essex surrendered and was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

On 19th February, 1560, Essex and some of his men were tried at Westminster Hall. He was accused of plotting to deprive the Queen of her crown and life as well as inciting Londoners to rebel. Essex protested that "he never wished harm to his sovereign". The coup, he claimed was merely intended to secure access for Essex to the Queen". He believed that if he was able to gain an audience with Elizabeth, and she heard his grievances, he would be restored to her favour. Essex was found guilty of treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.

In the early hours of 25th February, Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, attended by three priests, sixteen guards and the Lieutenant of the Tower, walked to his execution. In deference to his rank, the punishment was changed to being beheaded in private, on Tower Hill. Essex was wearing doublet and breeches of black satin, covered by a black velvet gown; he also wore a black felt hat.

As he knelt before the scaffold Essex made a long and emotional speech of confession where he admitted that he was "the greatest, the most vilest, and most unthankful traitor that ever has been in the land". His sins were "more in number than the hairs" of his head. It took three strokes of the axe to sever his head.

Queen Elizabeth was playing the virginals when a messenger brought confirmation of Essex's death. She received the news in silence. After a few minutes she began to play again. (55) Robert Lacey has pointed out: "This was a relationship of convenience founded initially perhaps upon passing infatuation but drawing its real life from the profit motive of one, the ageing insecurity of the other and the vanity of both. When the profit vanished, when age proved inescapable and when the vanity exhausted itself then the relationship collapsed."

Lettice Knollys not only lost her son. Her husband, Sir Christopher Blount, was tried for treason at Westminster Hall on 5th March. Found guilty, he was executed on Tower Hill on 18th March 1601, openly professing his Catholicism on the scaffold.

Queen Elizabeth died on 24th March, 1603. Lettice was still responsible £3,967 debts that was owed to the crown by her former husband, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. James VI decided to cancel these debts and also to allow Robert Devereux, to become 3rd Earl of Essex. Sir Robert Cecil became her main supporter during this period.

Lettice remained close to her daughters, Penelope Rich, Countess of Devonshire and Dorothy Percy, Countess of Northumberland, until their deaths in 1607 and 1619. It was claimed that in her late eighties she still walked a mile a day.

Lettice Knollys Devereux Dudley Blount died, aged 91, on 25th December 1634. She left instructions to be buried "at Warwick by my dear lord and husband the Earl of Leicester with whom I desire to be entombed". Her probate inventory valued her possessions at £6,645 11s. 4d.

On Christmas Day in 1821 Clara Barton was born. Barton was born in Oxford, Massachusetts, on 25th December, 1821. The daughter of a farmer, Barton began work as a schoolteacher at the age of fifteen.

In 1850 Barton moved to New York where she attended the Clinton Liberal Institute. Two years later she moved to Bordentown, New Jersey, where she established a free school. The school was very popular and grew rapidly. This upset the local men in the town and they tried to insist that the school should be run by a man. Barton refused and moved to Washington where she found work as a clerk in the U.S. Patent Office. In doing so, Barton became one of the first women to join the civil service.

On the outbreak of the American Civil War, Barton became a strong supporter of the Union cause. After hearing about the heavy casualties at Bull Run, Barton advertised in newspapers for medical supplies for the wounded. The response was so good that she was able to set up an agency distributing goods to soldiers. This involved the hiring of mules and wagons to take the supplies to the battlefields.

In July, 1862, Barton went to the front-line where she worked as an unpaid nurse for the Army of the Potomac. Barton continued as a freelance nurse until June, 1864, when she was employed as superintendent of nurses for the Army of the James. The following year President Abraham Lincoln appointed her as head of the Bureau of Records, a unit that attempted to search for missing soldiers.

After the war Clara Barton toured Europe and when the Franco-German War broke out in 1870, she organized the distribution of supplies to the French Army. During this period she became associated with the International Red Cross and after her return to the United States in 1873, Barton campaign to persuade the USA to sign the Geneva Convention. This was an agreement which established rules for the care of the sick and wounded in war.

In 1877 Barton organized the American National Committee, which three years later became the American Red Cross. The USA signed the Geneva Convention in 1884 and Congress agreed to support Barton's efforts to distribute relief during floods, earthquakes, famines, cyclones and other peacetime disasters.

The author of the History of the Red Cross (1882), Barton served as president of the American Red Cross between 1882 and 1904. Other books by Barton include The Red Cross in Peace and War (1899) and The Story of My Childhood (1907). Clara Barton died in Glen Echo, Maryland, on 12th April, 1912.

On this day in 1910 Mary Jane Clarke died. She had just been released from Holloway Prison, where she endured a hunger-strike and forced-feeding. Emmeline Pankhurst found her unconscious and she died soon afterwards as a result of a burst blood vessel on the brain. Clarke, like several suffragettes, probably died as a result of being forced fed in prison.

Mary Jane Clarke, the daughter of Robert Goulden and Sophia Crane, was born in Manchester in 1862. She was the younger sister of Emmeline Pankhurst. Her father was successful businessman with radical political beliefs. Goulden took part in the campaigns against slavery and the Corn Laws. Mary's mother was a passionate feminist and started taking her daughter to women's suffrage meetings in the 1870s.

The Pankhursts were members of the Manchester branch of the NUWSS. By 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst had become frustrated at the NUWSS lack of success. With the help of her two daughters, Christabel Pankhurst and Sylvia Pankhurst, and her sister Mary Clarke, she formed the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). At first the main aim of the organisation was to recruit more working class women into the struggle for the vote.

Mary Clarke organised a WSPU branch in Brighton. Acoording to Sylvia Pankhurst: "On ceasing to be Mrs. Pankhurst's deputy in the Registrarship, she had become an organiser for the W.S.P.U., and thereby found release from the regretful memories of an unhappy marriage."

By 1905 the media had lost interest in the struggle for women's rights. Newspapers rarely reported meetings and usually refused to publish articles and letters written by supporters of women's suffrage. In 1905 the WSPU decided to use different methods to obtain the publicity they thought would be needed in order to obtain the vote.

On 13th October 1905, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney attended a meeting in London to hear Sir Edward Grey, a minister in the British government. When Grey was talking, the two women constantly shouted out, "Will the Liberal Government give votes to women?" When the women refused to stop shouting the police were called to evict them from the meeting. Pankhurst and Kenney refused to leave and during the struggle a policeman claimed the two women kicked and spat at him. Pankhurst and Kenney were arrested and charged with assault.

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney were found guilty of assault and fined five shillings each. When the women refused to pay the fine they were sent to prison. The case shocked the nation. For the first time in Britain women had used violence in an attempt to win the vote. Members of the WSPU now became known as suffragettes.

On 25th June 1909 Marion Wallace-Dunlop was charged "with wilfully damaging the stone work of St. Stephen's Hall, House of Commons, by stamping it with an indelible rubber stamp, doing damage to the value of 10s." According to a report in The Times Wallace-Dunlop printed a notice that read: "Women's Deputation. June 29. Bill of Rights. It is the right of the subjects to petition the King, and all commitments and prosecutions for such petitionings are illegal."

Wallace-Dunlop was found guilty of wilful damage and when she refused to pay a fine she was sent to prison for a month. Christabel Pankhurst later reported: "Miss Wallace Dunlop, taking counsel with no one and acting entirely on her own initiative, sent to the Home Secretary, Mr. Gladstone, as soon as she entered Holloway Prison, an application to be placed in the first division as befitted one charged with a political offence. She announced that she would eat no food until this right was conceded."

Marion Wallace-Dunlop refused to eat for several days. Afraid that she might die and become a martyr, it was decided to release her after fasting for 91 hours. Soon afterwards other imprisoned suffragettes adopted the same strategy. Unwilling to release all the imprisoned suffragettes, the prison authorities force-fed these women on hunger strike.

Mary Jane Clarke began to organize the breaking the windows of buildings in Brighton. According to Sylvia Pankhurst: "Facing the rude violence of the seaside rowdies at Brighton, where she was stationed, she displayed a quiet, persistent courage, which made peculiarly large demands on one so sensitive. Exerting her frail physique to its utmost, she was grievously ill on the eve of Black Friday, and her Brighton comrades had begged her not to go. She had promised to take the easier course of arrest for window-breaking, and had telegraphed to Brighton from the police court."

On Christmas Day in 1951, a bomb exploded in Harry T. Moore's house killing him and his wife. Their friend, Stetson Kennedy, later wrote: "Moore was killed instantly. His wife died after a week of suffering. Even though Mrs. Moore said she had a "good idea" who planted the bomb, neither the local police nor Governor Warren's special investigator Elliott nor the F.B.I. bothered to take any statement from her before she died." Although members of the Ku Klux Klan were suspected of the crime, the people responsible were never brought to trial.

Harry Moore was born in Houston, Florida, on 18th November, 1905. After the death of his father in 1914 Moore was sent to live with his mother's sister in Daytona Beach. The following year he moved to Jacksonville where he lived with another of his aunts, Jessie Tyson.

In 1919 Moore began his studies at the Florida Memorial College. After graduating he became a schoolteacher in Cocoa, Florida. He later became principal of Titusville Colored School in Brevard County.

Moore established the Brevard County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) in 1934. With the support of the NAACP attorney, Thurgood Marshall, Moore led the campaign to obtain equal pay for African Americans working in Florida's schools. Moore also began organizing protests against lynching in Florida.

In 1944 he formed the Florida Progressive Voters League which succeeded in tripling the enrollment of registered black voters. By the end of the Second World War over 116,000 black voters were registered in the Florida Democratic Party. This represented 31 per cent of all eligible black voters in the state, a figure that was 51 per cent higher than any other southern state. Stetson Kennedy commented: "Moore was a two-fisted saintly fighter for democracy, who throughout his life was in the forefront of the struggle of his people for a greater measure of justice."

Moore's successful campaigns had made him unpopular with powerful political figures in Florida and in June 1946 he was dismissed from his teaching job. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People responded by appointing Moore as its organizer in Florida. Moore was a great success in this role and by 1948 the NAACP had over 10,000 members in Florida.

In 1949 Moore organized the campaign against the wrongful conviction of three African Americans, Walter Irvin, Sammy Shepherd, and 16-year-old Charles Greenlee, for the rape of a white woman in Groveland, Florida. Two years later, the Supreme Court ordered a new trial. On 6th November, 1951, while Sheriff Willis McCall was driving two of the defendants, Walter Irvin and Sammy Shepherd, back to Lake County for a pre-trial hearing, he shot them, killing Shepherd and critically wounding Irvin. McCall claimed that the handcuffed prisoners had attacked him while trying to escape. Irvin claimed that McCall had simply yanked them out of his car and started firing. The shooting created a national scandal. Harry Moore began calling for McCall's suspension and indictment for murder.

On Christmas Day in 1973 Gabriel Voisin died. Voisin was of the most productive aircraft designers of the First World War. On 5th October, 1914 the Voisin III, became the first Allied plane to shoot down an enemy aircraft.

Voisin became the standard Allied bomber in the early years of the war. Successive models were more powerful and over 800 were purchased by the French Army Air Service. The Royal Flying Corps and the Russian and Belgian airforces also used them in the war. The Voisin V first appeared in 1915. It was the first bomber to be armed with a cannon instead of a machine-gun.

On Christmas Day in 1977 blacklisted actor, Charlie Chaplin died. A strong opponent of racism, in 1937 Chaplin decided to make a film on the dangers of fascism. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography, attempts were made to stop the film being made: "Half-way through making The Great Dictator I began receiving alarming messages from United Artists. They had been advised by the Hays Office that I would run into censorship trouble. Also the English office was very concerned about an anti-Hitler picture and doubted whether it could be shown in Britain. But I was determined to go ahead, for Hitler must be laughed at." However, by the time The Great Dictator was finished, Britain was at war with Germany and it was used as propaganda against Adolf Hitler.

During the Second World War Chaplin played an active role in the American Committee for Russian War Relief. Others involved in this organization included Fiorello La Guardia, Vito Marcantonio, Wendell Willkie, Orson Welles, Rockwell Kent and Pearl Buck. Chaplin was also one of the major figures in the campaign during the summer of 1942 for the opening of a second-front in Europe.

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began to investigate people with left-wing views in the entertainment industry. In September 1947 Chaplin was subpoenaed to appear before the HUAC but three times his meeting was postponed. Unknown to Chaplin, J. Edgar Hoover, and the FBI, now had a 1,900 page file on his political activities. Hoover advised the Attorney General that when Chaplin left the country he should be allowed to return.

In 1952 Chaplin visited London for the premiere of Limelight. When he arrived back he discovered his entry permit revoked and had been denied the right to live in the United States. As Chaplin pointed out in his autobiography: "My prodigious sin was, and still is, being a non-conformist. Although I am not a Communist I refused to fall in line by hating them."

Chaplin, blacklisted from making films in Hollywood, responded by making A King in New York (1957). The film stars Chaplin as the deposed king of Estrovia who flees to America where he is tormented by McCarthy style investigations. Chaplin was once again accused of being pro-communist and the film was not released in the United States.

While in exile, Charlie Chaplin wrote his memoirs, My Autobiography (1964) and directed the movie, A Countess from Hong Kong (1966). Despite the objections of J. Edgar Hoover, in 1972 Chaplin was invited back to the United States to receive a special award from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He was also allowed to distribute his satire on McCarthyism, A King in New York.