On this day on 22nd April

John Edward Bowle, the author of Henry VIII (1964) claims that the young Henry Tudor benefitted from living in France: "Henry Tudor... had learnt in exile and diplomacy to keep his own council and to handle men: he could hold aloof and inspire fear, and became the greatest architect of the Tudor fortunes. Without the sheer blood lust of his contemporaries, he had a sardonic wit." (5)

King Louis XI of France agreed to Edward's request to try and capture Henry. However, this ended in failure when he was given sanctuary by a group of Breton noblemen in Brittany. On the death of Edward IV in 1483, his young sons, Edward and Richard, were usurped by their uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. He proclaimed himself Richard III and imprisoned the Princes in the Tower, where, almost certainly, he had them murdered.

Henry Tudor, as the head of the House of Lancaster, now had a claim to become king. Margaret Beaufort began plotting with various other opponents of Richard, to place her son on the throne. (6) Negotiations took place and in December 1483, Henry took an oath in Rennes Cathedral to marry Elizabeth of York were he to be successful in making himself king of England. (7)

The regents of the young King Charles VIII saw the advantage of supporting Henry Tudor against Richard III and provided him with money, ships, and men to seek the crown. In August 1485, Henry arrived in Wales with 2,000 of his supporters. He also brought with him over 1,800 mercenaries recruited from French prisons. While in Wales, Henry also persuaded many skillful longbowmen to join him in his fight against Richard. By the time Henry Tudor reached England the size of his army had grown to 5,000 men. (8)

Battle of Bosworth

When Richard heard about the arrival of Henry Tudor he marched his army to meet his rival for the throne. On the way, Richard tried to recruit as many men as possible to fight in his army, but by the time he reached Leicester he only had an army of 6,000 men. Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland, also brought 3,000 men but his loyalty to Richard was in doubt. (9)

Richard sent an order to Lord Thomas Stanley and Sir William Stanley, two of the most powerful men in England, to bring their 6,000 soldiers to fight for the king. Richard had been informed that Lord Stanley had already promised to help Henry Tudor. In order to persuade him to change his mind, Richard arranged for Lord Stanley's eldest son to be kidnapped.

On 21 August 1485, King Richard's army positioned themselves on Ambien Hill, close to the small village of Bosworth in Leicestershire. Henry arrived the next day and took up a position facing Richard. When the Stanley brothers arrived they did not join either of the two armies. Instead, Lord Stanley went to the north of the battlefield and Sir William to the south. The four armies now made up the four sides of a square.

Without the support of the Stanley brothers, Richard looked certain to be defeated. Richard therefore gave orders for Lord Stanley's son to be brought to the top of the hill. The king then sent a message to Lord Stanley threatening to execute his son unless he immediately sent his troops to join the king on Ambien Hill. Lord Stanley's reply was short: "Sire, I have other sons." (10)

Henry Tudor's forces now charged King Richard's army. Although out-numbered, Richard's superior position at the top of the hill enabled him to stop the rival forces breaking through at first. When the situation began to deteriorate, Richard called up his reserve forces led by Henry Percy, 4th Earl of Northumberland. However, Northumberland, convinced that Richard was going to lose, ignored the order.

Richard's advisers told him that he must try to get away. Richard refused, claiming that he could still obtain victory by killing Henry Tudor in personal combat. He argued that once the pretender to the throne was dead, his army would have no reason to go on fighting. With a loyal squadron of his household, he swept through to Henry's immediate bodyguard, striking down his standard-bearer. At this moment his horse died under him. (11) Polydore Vergil later reported that "King Richard alone was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies." (12)

King Henry VII

Henry VII was crowned on the battlefield with Richard's crown. He then marched into Leicester and then, slowly, onwards to London. On 3rd September he entered the capital in triumph. Elizabeth of York was placed in the London household of his mother, Margaret Beaufort. The parliament which met on 7th November asserted the legitimacy of Henry's title and annulled the instrument embodying Richard III's title to the throne. On 10th December 1485, the House of Commons, through their speaker Thomas Lovell, urged the king to act on his promise to marry "that illustrious lady Elizabeth, daughter of King Edward IV" and so render possible "the propagation of offspring from the stock of kings". (13)

Henry married Elizabeth of York and on 19th September 1486 she gave birth to a son, Prince Arthur. He was baptized on 24th September in Winchester Cathedral and named after the famous British hero whose fabulous exploits fill the pages of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Initially he was put into the care of women and his nursery at Farnham. This was headed by Dame Elizabeth Darcy. (14)

Francis Bacon has suggested that Henry's "aversion toward the house of York was so predominant in him as it found place not only in his wars and councils, but in his chamber and bed". However, Elizabeth's biographer, Rosemary Horrox, disagrees with this assessment. She quotes from several different sources that indicate that they had a happy marriage. (15)

Henry VII inherited a kingdom that was smaller than it had been for over 400 years. For the first time since the 11th century the realm did not include one French province. The only part of France still held by the English was the Marches of Calais, a strip of territory around the town of Calais. He held the title of "Lord of Ireland" since the 12th century, but effectively governed only an area that was roughly a semi-circle forty miles deep around Dublin.

It is estimated that Henry VII had three million subjects. Nearly every summer they were hit by epidemics of the Plague or Sweating Sickness which killed many of the population and improved the standard of living of the survivors, as the shortage of tenants and agricultural labourers kept rents low and wages high. Fifty thousand people lived in the capital city, London. The second largest city in England, Norwich, had 13,000 inhabitants; but Bristol and Newcastle were the only other towns with more than 10,000. Ninety per cent of the population lived in villages and on the farms in the countryside.

According to Jasper Ridley the English were famous throughout Europe for their hearty appetite. "It was said the English vice was overeating, as the German vice was drunkenness and the French vice lechery." (16) Bishop Stephen Gardiner commented: "Every country hath his peculiar inclination to naughtiness. England and Germany to the belly, the one in liquor, the other in meat; France a little beneath the belly; Italy to vanity and pleasures devised; and let an English belly have a further advancement, and nothing can stay it." (17)

Lambert Simnel

Henry VII was always worried about being overthrown by rivals for the thrown. Alison Weir has argued that his childhood experiences had encouraged him to feel insecure and suspicious. "He presented to the world a genial, smiling countenance, yet beneath it he was suspicious, devious and parsimonious. He had grown to manhood in an environment of treachery and intrigue, and as a result never knew security." (18)

In February 1487 Lambert Simnel appeared in Dublin and claimed to be Edward, earl of Warwick, son and heir of George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence, the brother of Edward IV, and the last surviving male of the House of York. (19) Polydore Vergil described him as as "a comely youth, and well favoured, not without some extraordinary dignity and grace of aspect". (20)

It is believed that John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, nephew of the Yorkist kings, was the leader of the conspiracy. He sailed to Ireland with over 1,500 German mercenaries. With this protection, Simnel was crowned as King Edward VI. Pole and his mercenaries, joined by 4,000 Irish troops, arrived on the Cumbrian coast on 4th June and marched across northern Lancashire before moving south. Henry's army, probably twice the size of Pole's, headed north from London. (21)

Henry was well-prepared, having positioned himself strategically to raise support, and advanced purposefully northwards from Leicester. "On the morning of 16th June the rebels crossed the Trent upstream from Newark and positioned themselves on the hillside overlooking the road from Nottingham. The battle of Stoke was a sharp and brutal encounter." (22) Henry's archers decimated the rebel army. The Earl of Lincoln was killed during the battle and Lambert Simnel was captured.

According to Polydore Vergil Henry VII spared Lambert Simnel, and put him to service, first in the scullery, and later as a falconer. (23) Jasper Ridley claims that this shows that "Henry VII... was not a vindictive man, and his style of government was quiet and efficient, never using more cruelty or deceit than was necessary. When he captured Lambert Simnel, the young tradesman's son who led the first revolt against him and was crowned King of England in Dublin, he did not put him to death, but employed him as a servant in his household." (24)

Perkin Warbeck

While visiting Cork in December 1491 Perkin Warbeck was persuaded to impersonate Richard, Duke of York, second son of Edward IV, who had disappeared eight years earlier together with his elder brother, Edward. In 1492 King Charles VIII of France began funding his campaign. This included being sent to Vienna to meet Emperor Maximilian. He gave his support to Perkin Warbeck but spies in the Maximilian's court told Henry VII about the conspiracy. As a result, several people in England were arrested and executed. (25)

In July 1495 Warbeck landed some of his men at Deal. They were quickly rounded up by the Sheriff of Kent and so Warbeck decided to return to Ireland. (26) However, on 20th November 1495 he went to see King James IV of Scotland in Stirling Castle. On 13th January 1496 James arranged for him to marry him to Lady Katherine Gordon, a distant royal relative. He also provided funding for Warbeck's 1,400 supporters. When Henry VII heard what was happening he began to plan an invasion of Scotland. (27)

Henry VII decided he would need to impose a new tax to pay the cost of raising an army. The people of Cornwall objected to paying taxes for war against Scotland and began a march on London. By 13th June, 1496, the Cornishmen, said to number 15,000, were at Guildford. The army of 8,000 that was being prepared against Scotland had to be rapidly diverted to protect London. On 16th June the rebel army reached Blackheath. When they saw Henry's large army, said to now number 25,000, some of them deserted. (28)

Henry VII sent a force of archers and cavalry round the back of the rebels. According to Francis Bacon: "The Cornish, being ill-armed and ill-led and without horse or artillery, were with no great difficulty cut in pieces and put to flight." A large number of the rebels were killed. Some of its leaders were hanged, drawn and quartered. He then proceeded to fine all those involved in the rebellion. It is claimed this raised £14,699. Bacon commented: "The less blood he drew, the more he took of treasure." (29)

Perkin Warbeck decided to take advantage on the Cornish rebellion by landing in Whitesand Bay on 7th September. He quickly recruited 8,000 Cornishmen but they were unsuccessful in taking Exeter. They retreated to Taunton but with news that Henry's army was marching into Cornwall, on 21st September, Warbeck escaped and sought sanctuary at Beaulieu Abbey. However, he was captured and was brought before Henry at Taunton Castle on 5th October. Warbeck was taken to London where he was repeatedly paraded through the city. (30)

Warbeck managed to escape but he was soon recaptured and on 18th June, 1499, he was sent to the Tower of London for life. The following year he became entangled in another plot. "Exactly what part he played in the conspiracy, and in its betrayal to the king on 3 August, is hard to establish, but Henry and his council resolved to punish all the principal participants." (31) Perkin Warbeck was hanged at Tyburn on 23rd November 1499.

Prince Arthur & Catherine of Aragon

Spain, along with France, were the two major powers in Europe. Henry VII constantly feared an invasion from his powerful neighbour. Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile were also concerned about the possible expansionism of France and responded favourably to Henry's suggestion of a possible alliance between the two countries. In 1487 King Ferdinand agreed to send ambassadors to England to discuss political and economic relations. (32)

In March 1488, the Spanish ambassador at the English court, Roderigo de Puebla, was instructed to offer Henry a deal. The proposed treaty included the agreement that Henry's eldest son, Arthur, should marry Catherine of Aragon in return for an undertaking by Henry to declare war on France. Henry enthusiastically "showed off his nineteen-month-old son, first dressed in cloth of gold and then stripped naked, so they could see he had no deformity." (33)

Puebla reported that Arthur had "many excellent qualities". However, they were not happy about sending their daughter to a country whose king might be deposed at any time. As Puebla explained to Henry: "Bearing in mind what happens every day to the kings of England, it is surprising that Ferdinand and Isabella should dare think of giving their daughter at all." (34)

The Treaty of Medina del Campo was signed on 27th March 1489. It established a common policy towards France, reduced tariffs between the two countries and agreed a marriage contract between Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon and also established a dowry for Catherine of 200,000 crowns. This was a good deal for Henry. At this time, England and Wales had a combined population of only two and a half million, compared to the seven and a half million of Castile and Aragon, and the fifteen million of France. Ferdinand's motivation was that Spanish merchants wishing to reach the Netherlands, needed the protection of English ports if France was barred to them. The English also still controlled the port of Calais in northern France. (35)

However, the marriage was not guaranteed. As David Loades points out: "The marriage of a ruler was the highest level of the matrimonial game, and carried the biggest stakes, but it was not the only level. Both sons and daughters were pieces to be moved in the diplomatic game, which usually began while they were still in their cradles. A daughter, particularly, might undergo half a dozen betrothals in the interests of shifting policies before her destiny eventually caught up with her." (36)

In August 1497, Catherine and Arthur were formally betrothed at the ancient palace of Woodstock. The Spanish ambassador, Roderigo de Puebla, standing proxy for the bride. Catherine arrival was delayed until Prince Arthur was able to consummating the marriage. Catherine was also encouraged to learn French as very few people in the English court spoke Spanish or Latin. Queen Elizabeth also suggested she accustom herself to drink wine, as the water in England was not drinkable. (37)

Catherine and Prince Arthur wrote several letters to each other. In October 1499 Arthur wrote to her thanking her for the "sweet letters" she had sent him: "I cannot tell you what an earnest desire I feel to see your Highness, and how vexatious to me is this procrastination about your coming. Let it be hastened, that the love conceived between us and the wished-for joys may reap their proper fruit." (38)

Catherine left the port of Corunna on 20th July 1501. Her party included the Count and Countess de Cabra, a chamberlain, Juan de Diero, Catherine's chaplain, Alessandro Geraldini, three bishops and a host of ladies, gentlemen and servants. It was considered too dangerous to allow Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile to make the journey. The sea-crossing was terrible: a violent storm blew up in the Bay of Biscay, and the ship was tossed about for several days in rough seas and the captain was forced to return to Spain. It was not until 27th September, that the winds died down and Catherine was able to leave Laredo on the Castilian coast. (39)

Catherine of Aragon arrived in England on 2nd October 1501. Arthur was just fifteen, and Catherine nearly sixteen. (40) As a high-born Castilian bride, Catherine remained veiled to both her husband and her father-in-law until after the marriage ceremony. Henry would have been concerned by her size. She was described as "extremely short, even tiny". Henry could not complain as Arthur, now aged fifteen, was very small and undeveloped and was "half a head shorter" than Catherine. He was also described as having an "unhealthy" skin colour. (41)

Arthur and Catherine married on 14th November 1501, at St Paul's Cathedral in London. That night, when Arthur lifted Catherine's veil he discovered a girl with "a fair complexion, rich reddish-gold hair that fell below hip-level, and blue-eyes". (42) Her naturally pink cheeks and white skin were features that were much admired during the Tudor period. Contemporary sources claim that "she was also on the plump side - but then a pleasant roundness in youth was considered to be desirable at this period, a pointer to future fertility". (43)

The couple spent the first month of their marriage at Tickenhill Manor. Arthur wrote to Catherine's parents telling them how happy he was and assuring them he would be "a true and loving husband all of his days". They then moved to Ludlow Castle. Arthur was in poor health and according to William Thomas, Groom of his Privy Chamber, he had been over-exerting himself. He later recalled he "conducted him clad in his night gown unto the Princess's bedchamber door often and sundry times." (44)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Alison Weir has argued that Arthur was suffering from consumption: "There was concern about the Prince's delicate health. He seems to have been consumptive, and had grown weaker since the wedding. The King believed, as did most other people, that Arthur had been over-exerting himself in the marriage bed." (45) Almost thirty years later Catherine deposed, under the seal of the confessional, that they had shared a bed for no more than seven nights, and that she had remained "as intact and incorrupt as when she emerged from her mother's womb". (46)

Antonia Fraser, the author of The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992) has argued that she believes the marriage was unconsummated. "In an age when marriages were frequently contracted for reasons of state between children or those hovering between childhood and adolescence, more care rather than less was taken over the timing of consummation. Once the marriage was officially completed, some years might pass before the appropriate moment was judged to have arrived. Anxious reports might pass between ambassadors on physical development; royal parents might take advice on their offsprings' readiness for the ordeal. The comments - sometimes remind one of those breeders discussing the mating of thoroughbred stock, and the comparison is indeed not so far off. The siring of progeny was the essential next step in these royal marriages, so endlessly negotiated." Fraser goes on to argue that the Tudors believed that bearing children too young might damage their chances of having further children. For example, Henry VII's mother, Margaret Beaufort, was only thirteen when she had him and never had any other children in the course of four marriages. (47)

On 27th March 1502, Arthur fell seriously ill. Based on the description of symptoms by his servants, he appeared to have been suffering from a bronchial or pulmonary condition, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis or some virulent form of influenza. David Starkey has suggested he might have been suffering from testicular cancer. (48) Antonia Fraser, believes that as Catherine was also ill at the same time, the both might have had sweating sickness.

Prince Arthur died on Saturday, 2nd April, 1502. (49) Elizabeth of York told Henry that she was still young enough to have more children. She became pregnant again and a daughter, Katherine was born prematurely on 2nd February 1503. She never recovered and died nine days later on 11th February, her thirty-seventh birthday, of puerperal fever. (50) Henry took her death very badly and "departed to a solitary place and would no man should resort unto him." (51)

Richard Empson & Edmund Dudley

Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has argued: "Henry VII... was an extremely clever man, possibly the cleverest man who ever sat on the English throne.... Henry's genius was mainly a genius for cautious manoeuvre, for exact timing, for delicate negotiation, for weighing up an opponent or a subordinate, and not least, a genius for organisation. It was allied to great patience and great industry. He was a competent soldier, but always chose peace instead of war as being so much cheaper and so much safer. These are admirable and invaluable qualities for a political leader in troubled times." (52)

Henry VII was careful in the selection of his key officials. During his reign Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley became the king's most trusted ministers. (53) Jasper Ridley has pointed out that Empson and Dudley were the chief instruments of the king's financial policy: "They seem to have been almost universally hated throughout England. They were accused of acting illegally when they extorted large sums of money from wealthy landowners under the recognisance system, and of not only obtaining this money for the King, but of enriching themselves in the process." (54) Christopher Morris, the author of The Tudors (1955) has suggested that Dudley was the king's most "unpopular and unscrupulous minister". (55)

Empson's biographer, Margaret Condon, has pointed out: "As chancellor, Empson continued Bray's efforts to increase revenue, authorizing the raising of rents or disallowance of rebates, and directing surveys and audits, enclosures of commons, and investigations of feudal incidents. The drive to maximize feudal revenues, to pursue old bonds, and to manipulate the penal laws in the king's interests was centred on the council learned, even in those cases where parallel actions were sued at common law.... The methods he used included the use of promoters for prosecution; imprisonment to facilitate settlement by fine or composition; and summonses issued (as in other council courts) by privy seal... His particular responsibilities were the authorization of pardons, countersigned by the king; the finding and traverse of intrusions and the issue of commissions of concealments; pardons and forfeitures on outlawry; wards and liveries of lands. Most actions or grants of grace resulted in fines to the king, in amounts and by methods which led Polydore Vergil and others to characterize both Empson and Dudley as extortioners." (56)

Roger Lockyer has argued that "Empson was the only prominent member of Henry's Council to come from a bourgeois background - his father was a person of some importance in the town of Towcester - and the idea that Henry VII surrounded himself with 'middle-class men' is very misleading. The gentry, whose numbers and importance in the royal administration were steadily increasing, were close in blood and social assumptions to the aristocracy, and counted themselves among the upper ranks of English society." (57)

Catherine of Aragon

Henry VII was keen to maintain his alliance with Ferdinand of Aragon and recently widowed, offered to marry Catherine of Aragon himself. As he was 46 years-old and in poor health, this idea was rejected and on 23rd June 1503, he signed a new treaty betrothing Catherine to Henry, his only surviving son, then aged twelve. The treaty also contained an agreement that, as the parties were related, the signatories bound themselves to obtain the necessary dispensation from Rome. At that time, Christians believed it was wrong for a man to marry his brother's wife. It was also agreed that the marriage would take place as soon as Henry completed his fifteenth year. In the meantime Henry allowed Catherine £100 a month, and appointed one of his own surveyors to oversee the management of it. (58)

Ferdinand wrote on 23rd August 1503: "It is well known in England that the Princess is still a virgin. But as the English are much disposed to cavill, it has seemed to be more prudent to provide for the case as though the marriage had been consummated... the dispensation of the Pope must be in perfect keeping with the said clause to the marriage treaty... The right of Succession (of any child born to Catherine and Henry) depends on the undoubted legitimacy of the treaty." (59)

Catherine was allocated Durham House in London. She was frequently ill, probably with tertian malaria. Her knowledge of English was still imperfect in 1505, which upset both Ferdinand of Aragon and Henry VII, who reduced her allowance. Catherine moved to Richmond Palace but complained to her father about her poverty and her inability to pay her servants, and her demeaning dependence on Henry's charity. She told her father she had managed to buy only two dresses since she came to England from Spain six years earlier.

Catherine was kept apart from Prince Henry, complaining in 1507 that she had not seen him for four months, although they were both living in the same palace. (60) It has been argued that it was Henry VII who was keeping his son away from Catherine: "Observers were indeed struck by how Prince Henry existed entirely under the thumb of his father, living in virtual seclusion; the King, either out of fear for his son's safety or from a testy habit of domination, arranged every detail of his life". (61)

King Ferdinand feared that Catherine would not be allowed to marry Henry, who was growing into a handsome prince. Roderigo de Puebla told Ferdinand: "There is no finer youth in the world than the Prince of Wales". He told him of his startling looks, including his strong athletic limbs "of a gigantic size" was already beginning to arouse the admiration of the Royal Court. (62)

Henry VII died on 21st April 1509. His personal fortune of £1.5 million illustrated the success of his foreign policy and the commercial prosperity that England enjoyed under his rule.

On this day in 1814 Angela Burdett-Coutts, the youngest of the six children of Sir Francis Burdett, the Radical MP, was born at 80 Piccadilly, London, on 21st April, 1814. Angela's mother, Sophia Coutts, was the daughter of Thomas Coutts, the wealthy banker.

Burdett had been having an affair with Jane Harvey, the Countess of Oxford and as Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978) has pointed out: "She was the child of the reconciliation between Sir Francis and Sophia. But Sophia still had to endure the strain of conflict between husband and father. Thomas Coutts's attitude to his son-in-law can be imagined. During the years before and after Angela's birth even his tolerance was strained. But there was no moralizing on the subject of infidelity. For in the years when Sir Francis was finding release in the arms of Lady Oxford... he was having a relationship with an enchanting young actress called Harriot Mellon." Burnett later told his daughter: "I loved your mother and if one mortal was attracted warmly to another, I am persuaded she was to me - in spite of many errors and sometimes being dissatisfied with my conduct."

Sir Francis Burdett was the leader of the Radicals in the House of Commons and the most controversial MP in England. Burdett introduced motions for parliamentary reform and supported all attempts to expose government corruption. Burdett also supported the campaign against the slave trade. In 1816 he attacked William Wilberforce when he refused to complain about the suspension of Habeas Corpus. Burdett commented: "How happened it that the honourable and religious member was not shocked at Englishmen being taken up under this act and treated like African slaves?" Wilberforce replied that Burdett was opposing the government in a deliberate scheme to destroy the liberty and happiness of the people."

In 1819 her father led the campaign for an independent inquiry into the Peterloo Massacre. Burdett wrote to the Westminster electors on 22nd August 1820 condemning the massacre and calling on "the gentlemen of England" to join the masses in protest meetings. Burdett was prosecuted for seditious libel, found guilty, sentenced to the Marshalsea Prison for three months, and fined £2,000. According to her biographer, Edna Healey: "She saw too little of her brilliant and stimulating father in these years... he was a legend absent and longed for. The child waiting in the quiet Bath crescent would never forget the excitement of his homecomings, the clamour of the dogs, the clatter of the horses signalling the arrival of the father who, present or absent, dominated her life. At the London window she watched him brought home in triumph and remembered him forever as heroic and larger than life."

In 1822 her wealthy grandfather, Thomas Coutts, died. He left his whole estate to his much younger second wife, the former actress, Harriot Mellon. At first, Angela's mother, considered opposing the will, but after taking legal advice she abandoned the plan. Harriot later became involved with William Beauclerk, 9th Duke of St Albans, who was 23 years her junior. Walter Scott wrote: "If the Duke marries her, she has the first rank. If he marries a woman older than himself by twenty years, she marries a man younger in wit by twenty degrees... The disparity of ages concerns no-one but themselves so they have my consent to marry if they can get each other. The couple did marry and she became the Duchess of St Albans.

Angela was educated by a succession of tutors at her family's country residences, in Ramsbury and Foremark. In 1826 Sir Francis Burdett appointed Hannah Meredith as her governess. Later that year Lady Burdett took Angela and her sisters, on a three year tour of Europe. Hannah went with them. As Angela's biographer pointed out: "Angela, at twelve, was intelligent, equable in temperament but plain and lanky and needed a good governess... Bubbling, vital, intelligent and shrewd, Hannah was the perfect companion and teacher for the serious girl, bringing much needed zest into the querulous world of spas and watering places."

Harriot Mellon, Duchess of St Albans, decided that when she died the money she inherited from Thomas Coutts would be returned to the Coutts family. Over several years she carefully observed her former husband's grandchildren. Her first choice was Dudley Coutts Stuart, who was "serious, idealistic and hard-working". However, she turned against him when he married Christine Bonaparte, the niece of Napoleon Bonaparte. She now turned her attention to other candidates.

On the marriage of her sister Sophia in 1833, Angela began to take over the role of companion to her father, Sir Francis Burdett. During this period she met some very interesting people. This included two young politicians, William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli. According to her biographer, Edna Healey: "She inherited many of her father's humanitarian views and, among other qualities, his natural and persuasive power as a public speaker... Her grandfather's Coutts banking connection facilitated her introduction to a wide circle of European royalty and nobility. In Paris she was introduced to the French royal family, notably the future king Louis-Philippe and his sister Adelaide, who were friends of her mother and grandfather, and so established a lifelong connection of her own with the Orléans family."

Harriot Mellon Coutts, Duchess of St Albans, died on 6th August, 1837. The will was read in the presence of the various relatives. To the surprise of all concerned, it was announced that almost the entire estate was left to Angela. This amounted to some £1.8 million (£165 million in 2012 money). The duchess's will made the inheritance conditional on Angela not marrying a foreign national, in which event it would pass to the next in line, and stipulated that her successors take the surname of Coutts. It has been claimed that after Queen Victoria she was the wealthiest woman in England. The Morning Herald estimated that her fortune amounted to "the weight in gold is 13 tons, 7 cwt, 3 qtrs, 13 lbs and would require 107 men to carry it, supposing that each of them carried 289 lbs - the equivalent of a sack of flour". Angela gave her mother, Lady Sophia Burdett, £8,000 a year and all her sisters received an allowance of £2,000 a year.

Later that year Angela Burdett-Coutts established a new home at 1 Stratton Street, Piccadilly. Angela was joined by her former governess, Hannah Meredith. She was engaged to be married to Dr William Brown, but agreed to postpone the event in order to support Angela during this difficult period. As a result of her newly acquired fortune, she received a constant flow of begging letters.

Angela was also besieged with proposals of marriage. Richard Monckton Milnes commented: "Miss Coutts likes me because I never proposed to her. Almost all the young men of good family did: those who did their duty by their family always did." Punch Magazine jokingly reported: "The world set to work, match-making, determined to unite the splendid heiress to somebody. Now, she was to marry her physician; and now, she was to become a Scotch countess. The last husband up in the papers is Louis-Napoleon. How Miss Coutts escaped Ibrahim Pacha when he was here, is somewhat extraordinary."

Miss Coutts appealed to Edward Marjoribanks for help. When Sir Francis Burdett heard about this he wrote to his daughter: "Why did you not send for me? I could have put an end to your annoyance better than anybody but you mentioned it so slightly I had no idea of its having been so tormenting and distressing. I should like to know the names of the magistrates you say behaved so odd and how. I am really mortified at not having been sent for and think moreover it must wear a strange and unaccountable appearance and cause unpleasant and unfavourable animadversions in the not-over good natured."

Her most persistent suitor was Richard Dunn, a bankrupt barrister. According to The Spectator Magazine: "Dunn had blockaded Miss Coutts for two mortal years. If she went to Harrogate he followed her; if she returned to Stratton Street he entrenched himself in the Gloucester Hotel; if she walked in the Parks, he was at her heels; if she took a walk in a private garden, he was waving handkerchiefs over the wall, or creeping through below the hedge. With his own hands he deposited his card in her sitting-room; he drove her from church, and intruded himself into the private chapel in which she took refuge. In vain her precaution to have policemen constantly in her hall, and a bodyguard of servants when she moved abroad."

Angela Burdett-Coutts had no intention of getting married. Under the guidance of Sir Francis Burdett, she decided to give a large percentage of the money to good causes, especially the relief of poverty. Her father also encouraged her to be interested in science and she provided funds for research in physics, geology, archaeology and the natural sciences. At his home she met men like Charles Babbage, Michael Faraday and Charles Wheatstone. In 1839 she provided financial backing for Babbage's "calculating engine", the forerunner of the modern computer.

Miss Burdett-Coutts met Charles Dickens for the first time in 1839 at the home of Edward Marjoribanks, who ran Coutts Bank. Her father, Sir Francis Burdett had been impressed with Dickens's early novels, The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist. Dickens was immediately taken by and later told her in a letter: "I have never begun a book or begun anything of interest to me or done anything of importance to me... (since) I first dined with you at Mr Marjoribanks." Later that year he wrote to her about their "intimate" friendship. His biographer, John Forster , has pointed out: "The marked attentions shown him by Miss Coutts which began with the very beginning of his career were invariably welcome."

Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978), pointed out: "From the first Angela was enchanted by Dickens. In the first flow of his sudden fame he was remarkably attractive. From his luxuriant hair, lustrous eyes and fresh glowing complexion to the brilliant buckles of his shoes there was such a shine about him. There was also a frankness of expression, a look of goodness that Miss Coutts, like other ladies of the day, found irresistible. If there was a little too much of the dandy in his dress she could forgive him. She had, after all seen Disraeli in full bloom."

John Cam Hobhouse, one of her admirers, later recalled: "If her complexion were good she would have a pleasing face. Her figure, though not sufficiently full, is good. Her voice is melodious, her expression sweet and engaging." Burdett-Coutts was always concerned about her "over-sensitive skin". Charles Dickens wrote giving her advice on how to deal with the problem: "I am convinced that the most important thing of all for health is to keep up the circulation on the surface of the person which is in fact keeping the skin in order. Above all keep your feet dry and warm. If mine are very cold I rub them against each other at night as I have entreated you to do."

In September 1843 Dickens approached her about the possibility of supporting Ragged Schools. These early schools provided almost the only secular education for the very poor. Dickens had provided a small sum of money from one of these schools in London. Burdett-Coutts was attracted to the idea and offered to provide public baths for them and a larger school room. She also gave her support to Lord Shaftesbury, who in 1844 formed the Ragged School Union and during the next eight years over 200 free schools for poor children were established in Britain.

Angela's mother, Lady Sophia Burdett-Coutts, died on 12th January 1844. Her father, Sir Francis Burdett died eleven days later. They were both buried in the family vault in Ramsbury Church. Angela wrote: "They were lovely in their lives and in their deaths they were not divided." Dickens wrote to Angela's companion, Hannah Meredith, showing concern for her health: "I have often thought of Miss Coutts in her long and arduous attendance upon her poor mother; and but that I know how such hearts as hers are sustained in such duties, should have feared for her health. For her peace of mind in this and every trial and for her gentle fortitude always, no one who knows her truly, can be anxious in the least. If she has not the material of comfort and consolation within herself there are no such things in any creatures nature."

Soon after the death of her parents, Miss Burdett-Coutts became very friendly with the country's leading elder statesman, the Duke of Wellington. At first he advised her on business matters. At the time she was in dispute with Edward Marjoribanks, who ran Coutts Bank. Burdett-Coutts wanted to raise the salaries of the clerks in the bank. Wellington helped her draft a letter to Marjoribanks that stated: "There are points connected with the management of my House upon which I cannot alter my opinions, founded as they are upon the invariable practice of my grandfather.... I am anxious to know whether you will consent to have prepared by next week our arrangement for a general rise in public salaries of the clerks of the House; which contrary to the practice of my grandfather has not taken place for some years."

On 19th December 1844, Angela's companion, Hannah Meredith, married Dr. William Brown. She rented them the adjoining house in Stratton Street, Piccadilly, that she also owned. Their drawing-room doors opened directly into her own house, and so she did not feel deserted by Hannah. Her husband became her doctor. Edna Healey has argued: "Dr Brown was a welcome addition to her aides. A plain, simple man, he had risen from humble origins by his own efforts and in the years following he was to be an invaluable adviser in her work for education among the poor."

Charles Dickens was a regular visitor to Miss Burdett-Coutts' home where they discussed ways of working together. On 26th May, 1846, Dickens sent her a fourteen-page letter concerning his plan for setting up an asylum for women and girls working the London streets as prostitutes. He began the letter by explaining that these women were living a life "dreadful in its nature and consequences, and full of affliction, misery, and despair to herself." He went on to say that he hoped it could be explained to each woman who asked for help "that she is degraded and fallen, but not lost, having this shelter; and that the means of Return to Happiness are now about to be put into her own hands."

Dickens went on to argue: "I do not think it would be necessary, in the first instance at all events, to build a house for the Asylum. There are many houses, either in London or in the immediate neighbourhood, that could be altered for the purpose. It would be necessary to limit the number of inmates, but I would make the reception of them as easy as possible to themselves. I would put it in the power of any Governor of a London Prison to send an unhappy creature of this kind (by her own choice of course) straight from his prison, when her term expired, to the Asylum. I would put it in the power of any penitent creature to knock at the door, and say For God's sake, take me in. But I would divide the interior into two portions; and into the first portion I would put all new-comers without exception, as a place of probation, whence they should pass, by their own good-conduct and self-denial alone, into what I may call the Society of the house."

His idea was to begin with about thirty women. "What they would be taught in the house, would be grounded in religion, most unquestionably. It must be the basis of the whole system. But it is very essential in dealing with this class of persons to have a system of training established, which, while it is steady and firm, is cheerful and hopeful. Order, punctuality, cleanliness, the whole routine of household duties - as washing, mending, cooking - the establishment itself would supply the means of teaching practically, to every one. But then I would have it understood by all - I would have it written up in every room - that they were not going through a monotonous round of occupation and self-denial which began and ended there, but which began, or was resumed, under that roof, and would end, by God's blessing, in happy homes of their own."

Angela Burdett-Coutts had already become aware of the problem of prostitution. She had seen them parading every night outside her home in Piccadilly. It had been estimated by one newspaper reporter, Henry Mayhew, that London had around 80,000 prostitutes. Mayhew argued that one group that was particularly vulnerable were young female servants. He claimed that there was about 10,000 of them out on the streets on the move between jobs. If they did not have good character references from their last employer, they would be in danger of long-term unemployment and the temptation to become prostitutes. In an article in the Westminster Review by William Rathbone Greg wrote: "The career of these women (prostitutes) is a brief one, their downward path a marked and inevitable one; and they know this well. They are almost never rescued, escape themselves they cannot."

Although her close friend, the Duke of Wellington, advised her against getting involved. As one biographer has explained: "He could not understand her enthusiasm for social reform, for popular education, for clearing slums and sewers, all these were outside his comprehension." Despite his protests, she eventually agreed to fund Dickens's proposal, which was estimated at costing around £700 a year (£50,000 in 2012 money).

As Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011), has pointed out: "She gave him almost free rein in setting it up. He needed to find a house large enough to take up to a dozen or so young women, sharing bedrooms, plus a matron and her assistant - his early plan to take thirty was given up as impractical... In May 1847 he came upon a small, solid brick house near Shepherd's Bush, then still in the country, but well connected with central London by the Acton omnibus. The house was already named Urania Cottage but from the first he called it simply the Home, the idea that it should feel like a home rather than an institution being so important to him. He liked the fact that it stood in a country lane, with its own garden, and saw at once that the women could have their own small flowerbeds to cultivate. There was also a coach house and stables which could be made into a laundry."

During this period Miss Burdett-Coutts became very close to the Duke of Wellington. On 19th August 1846, he wrote: "I hope you will always write to me whenever you wish to communicate with a friend." When they were apart he wrote to her daily, sometimes twice a day. It has been estimated that during the relationship Wellington sent Miss Burdett-Coutts, over 800 letters. They often sent each other the "product of their walks", a flower, a delicate leaf, a fragrant herb. The author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978), has speculated: "Was he her lover? Undoubtedly their relationship was very close. The tone of his letters, the winding staircase to his private rooms, the intertwined locks of hair show how close it was. But it is easier to believe that she secretly married him than that she was his mistress. There is no proof of such a marriage, only persistent rumours in both their families."

Granville Leveson-Gower recorded in his diary: "The Duke of Wellington was astonishing the world by a strange intimacy he has struck up with Miss Coutts with whom he passes his life, and all sorts of reports have been rife of his intention to marry her. Such are the lamentable appearances of decay in his vigorous mind, which are the more to be regretted because he is in Most enviable circumstances, without ny political responsibility, vet associated with public affairs, and surrounded with every sort of respect and consideration on every side - at Court, in Parliament, in society, and in the country."

On 7th February 1847, Miss Burdett-Coutts proposed to Duke of Wellington, despite the age difference, he was seventy-eight and she was thirty-three. Wellington answered her in a letter the following day: "My dearest Angela, I have passed every moment of the evening and night since I quitted you in reflecting upon our conversation of yesterday, every word of which I have considered repeatedly. My first duty towards you is that of friend, guardian, protector. You are young, my dearest! You have before you the prospect of at least twenty years of enjoyment of happiness in life. I entreat you again in this way, not to throw yourself away upon a man old enough to be your grandfather, who, however strong, hearty and healthy at present, must and will certainly in time feel the consequences and infirmities of age... My last days would be embittered by the reflection that your life was uncomfortable and hopeless."

Miss Burdett-Coutts also became very close to Michael Faraday. According to Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978): "In Michael Faraday she found a brilliant, searching mind combined with a simple child-like faith that matched her own. The greatest experimental genius of his time, the man who discovered the laws of electrolysis, of light and magnetism, he was at ease in her company. The blacksmith's son who hated the social scene, made exceptions for her... As their friendship grew, he would call on her after the Friday lectures at the Royal Institution, eventually persuading her to apply for membership of the Royal Society."

On 19th January, 1847, Faraday wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts: "For twenty years I have devoted all my exertions and powers to the advancement of science in this Institution; and for the last ten years or more I have given up all professional business and a large income with it for the same purpose... Although I earnestly desire to see lady members received amongst us, as in former times, do not let anything I have said induce you to do what may be not quite agreeable to your own inclinations." In February 1847 she became a full member of the Royal Society.

Charles Dickens continued to search for a property suitable for his home for prostitutes. Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011), has pointed out: "She (Angela Burdett-Coutts) gave him almost free rein in setting it up. He needed to find a house large enough to take up to a dozen or so young women, sharing bedrooms, plus a matron and her assistant - his early plan to take thirty was given up as impractical... In May 1847 he came upon a small, solid brick house near Shepherd's Bush, then still in the country, but well connected with central London by the Acton omnibus. The house was already named Urania Cottage but from the first he called it simply the Home, the idea that it should feel like a home rather than an institution being so important to him. He liked the fact that it stood in a country lane, with its own garden, and saw at once that the women could have their own small flowerbeds to cultivate. There was also a coach house and stables which could be made into a laundry."

The lease was agreed in June 1847 and soon afterwards Dickens started interviewing possible matrons. Miss Burdett-Coutts appointed Dr. James Kay-Shuttleworth, a Poor Law Commissioner, who had written about education and the working-class, to help Dickens with the task. However, the two men disagreed about the role of religious education in the home. Dickens told her that Kay-Shuttleworth's theorizing made him feel as if he had "just come out of the Desert of Sahara where my camel died a fortnight ago."

In October 1847, Dickens published a leaflet that he gave to prostitutes encouraging them to apply to join Urania Cottage: "If you have ever wished (I know you must have done so, sometimes) for a chance of rising out of your sad life, and having friends, a quiet home, means of being useful to yourself and others, peace of mind, self-respect, everything you have lost, pray read... attentively... I am going to offer you, not the chance but the certainty of all these blessings, if you will exert yourself to deserve them. And do not think that I write to you as if I felt myself very much above you, or wished to hurt your feelings by reminding you of the situation in which you are placed. God forbid! I mean nothing but kindness to you, and I write as if you were my sister." Dickens interviewed every young women who responded to the leaflet or who was recommended to him by prison governors, magistrates or the police. Once accepted she would be told that no one would ever mention her past to her and that even the matrons would not be informed about it. She was advised not to talk further about her own history to anyone else. Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts on 28th October, 1847: "We have now eight, and I have as much confidence in five of them, as one can have in the beginning of anything so new."

The home was opened in November 1847. There were four girls to begin with, two were coming in the following week. Mrs Holdsworth had been appointed matron and Mrs Fisher as her assistant. Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts: "I wish you could have seen them at work on the first night of this lady's engagement - with a pet canary of hers walking about the table, and the two girls deep in my account of the lesson books, and all the knowledge that was to be got out of them as we were putting them away on the shelves." According to Dickens, the first girl who entered Urania Cottage, cried with joy when she saw her bed.

The women slept three or four to a bedroom, each with her own bed. They got up at six in the morning, and they had to make each other's beds, and were required to inform on anyone who was hiding alcohol. They had short prayers, twice daily. Dickens was determined to avoid preaching, heavy moralizing and calls for penitence. He told Miss Burdett-Coutts that they had to be very careful about the appointment of a chaplain: "The best man in the world could never make his way to the truth of these people, unless he were content to win it very slowly, and with the nicest perception always present to him... of what they have gone through. Wrongly addressed they are certain to deceive."

Dickens later recalled the type of women he recruited for Urania Cottage. "Among the girls were starving needlewomen, poor needlewomen who had robbed... violent girls imprisoned for committing disturbances in ill-conducted workhouses, poor girls from Ragged Schools, destitute girls who have applied at police offices for relief, young women from the streets - young women of the same class taken from the prisons after under-going punishment there as disorderly characters, or for shoplifting, or for thefts from the person: domestic servants who had been seduced, and two young women held to bail for attempting suicide."

Miss Burdett-Coutts thought that the women should wear dark clothes but Dickens insisted they should be given dresses in cheerful colours they would enjoy wearing. She was supported by George Laval Chesterton, the governor of Coldbath Fields Prison, who argued that the "love of dress is the cause of ruin of a vast number of young women in humble circumstances". Augustus Tracey, the governor of Tothill Fields Prison, agreed saying that in twenty years' experience he had found the excessive love of dress often resulted in an "early lapse into crime - for girls it was equal as a cause of ruin as drink was for men." He wrote: "These people want colour... In these cast-iron and mechanical days, I think even such a garnish to the dish of their monotonous and hard lives, of unspeakable importance... I have made them as cheerful in appearance as they reasonably could be - at the same time very neat and modest. Three of them will be dressed alike, so that there are four colours of dresses in the Home at once; and those who go out together, with Mrs Holdsworth, will not attract attention, or feel themselves marked out, by being dressed alike."

Dickens also arranged for the women to be well fed, with breakfast, dinner and tea at six, being their last meal of the day. There was schooling for two hours every morning where they were taught to read and write. They took it in turns to read aloud while they did their needlework, making and mending their own clothes. The women also had plots in the garden where they could grow vegetables. Dickens also paid for his friend, John Hullah, to give singing lessons. The inmates did all the household tasks, which were rotated weekly. They also made soup that was distributed to local people on poor relief.

Jenny Hartley, the author of Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women (2008) has pointed out that the women were not allowed out on their own and the matron would take them out individually or in small groups. Nor were they allowed unsupervised visits or private correspondence as Dickens was afraid that old associates might try to draw them back to the life they had left behind. They were given marks for good behaviour and lose marks for bad behaviour. These marks were worth money and this would be saved for them to use when they left the house.

Miss Burdett-Coutts was concerned about the religion of the staff. She objected to Dickens employing Mrs Fisher, a Nonconformist. Dickens, who had been impressed by her "mild sweet manners" agreed to sack her, but was not happy about it: "I have no sympathy whatever with her private opinions, I have a very strong feeling indeed - which is not yours, at the same time I have no doubt whatever that she ought to have stated the fact of her being a dissenter to me, before she was engaged... With these few words and with the fullest sense of your very kind and considerate manner of making this change, I leave it."

Mrs Holdsworth left her post but Dickens was very pleased with his appointment of Georgina Morson, as matron. She was a widow of a doctor. She had three young children but her mother agreed to look after them so she could do the job. Morson provided them with good food, an orderly life, training in reading, writing, sewing, domestic work, cooking and laundering. It has been claimed that she looked after them so well that they wept when they parted from her.

If any of the women caused trouble they were expelled from the home and deprived of the nice clothes they had been given. Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts about he dealt with Isabella Gordon after she had caused problems for Mrs Morson: "As she had no clothes she departed, of necessity, in those she had on, and in one of the rough shawls. We gave her half a crown to get a night's lodging... The girl herself, now that it had really come to this, cried, and hung down her head, and when she got out of the door, stopped and leaned against the house for a minute or two before she went to the gate - in a most miserable and wrteched state... We passed her in the lane, afterwards, going slowly away, and wiping her face with her shawl."

Dickens was aware that given her situation Isabella Gordon would return to a world of prostitution. A few days later he wrote that month's episode of David Copperfield, that included a passage about Martha Endell, who was returning to her life as a prostitute: "Then Martha arose, and gathering her shawl about her, covering her face with it, and weeping aloud, went slowly to the door. She stopped a moment before going out, as if she would have uttered something or turned back; but no word passed her lips. Making the same low, dreary, wretched moaning in her shawl, she went away." In the novel Martha later emigrates to Australia where she marries happily. It is unlikely that Isabella Gordon would have shared a similar fate.

Dickens also had trouble with Sesina Bollard. He described her as "the most deceitful little minx in this town - I never saw such a draggled piece of fringe upon the skirts of all that is bad... she would corrupt a Nunnery in a fortnight." Another girl, Jemima Hiscock, "forced open the door of the little beer cellar with knives and got dead drunk". He accused Jemima of using "the most horrible language" and it was thought the beer must have been, "laced with spirits from over the wall". The most disturbing incident was when the matron found a police constable "yesterday morning between four and five... in the parlour with Sarah Hyam."

Dickens expected that each of them would live at the cottage for about a year before being given a supervised place on an emigrant ship, by which time they would be well nourished, healthy, better educated and in a better state to manage their lives. Dickens hoped they would find husbands but Miss Burdett-Coutts about former prostitutes marrying. The first inmate left for Australia in January 1849. Dickens later discovered that she had returned to prostitution on the ship that was taking her to her new home. Dickens told Miss Burdett-Coutts that this news caused "heavy disappointment and great vexation."

In 1849 Dickens published David Copperfield. Some critics have suggested that Agnes Wickfield shows similarities to Angela Burdett-Coutts. The author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978), has argued: "As the plot unfolded she must have seen in Agnes Wickford more and more clearly the image of herself. It was not merely the superficial clues - their initials were the same, there were repeated echoes of her name." Dickens wrote later: "Of all my books, I like this the best. It will be easily believed that I am a fond parent to every child of my fancy, and that no one can ever love that family as dearly as I love them; but, like many fond parents, I have in my heart of hearts a favourite child, and his name is David Copperfield."

Dickens used to trawl the streets looking for women to enter Urania Cottage. In April 1850, he wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts about his "nightly wanderings into strange places". He tried to sell the idea by pointing out they would be prepared at the home for emigration to Australia. Dickens complained that in their "astonishing and horrible ignorance" the women he talks to are often confuse "emigration and transportation". In a letter to Daniel Maclise he admitted that he sometimes rejected women because they were not "interesting". In letters to Georgina Morson it has been argued by one observer that "some passages suggest that his interest in the girls was less than healthy." Jenny Hartley, the author of Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women (2008), rejects this view: "if Dickens had wanted to have sex with prostitutes and working-class girls, I do not think he would have set up a bordello".

In letters to Georgina Morson it has been argued by one observer that "some passages suggest that his interest in the girls was less than healthy." Jenny Hartley, the author of Charles Dickens and the House of Fallen Women (2008), rejects this view: "if Dickens had wanted to have sex with prostitutes and working-class girls, I do not think he would have set up a bordello". However, it is worth noting that a large number of the women who entered Urania Cottage were not prostitutes. They were young women who had been imprisoned for crimes such as stealing. The prison governors of Coldbath Fields Prison and Tothill Fields Prison, recommended them to Dickens as they feared that they would resort to prostitution as no other means of making money was available to them.

For example, Sarah Wood was an eighteen-year-old girl, had been sent to prison for fraud. Her scam involved calling at upmarket shops, fashionably dressed. She ordered several items of clothes and asked for them to be delievered to the family home in Finsbury Square, to be paid on delivery. However, she asked to take some of the dresses with her. She managed to deceive at least three shopkeepers with her fictional family and address before she was caught and sent to prison. Dickens took a great deal of interest in Sarah until she left the home, refusing to be sent to Australia.

Another woman who entered Urania Cottage who was not a prostitute was Mary Ann Stonnell. Newspaper reports described her as "a slight girl of thirteen" who was used by a criminal gang to get into houses and shops through the fanlight over the front door. When they were eventually caught, Mary Ann was given a short prison sentence and the men were transported for seven years. Dickens tried to develop a good relationship with Mary Ann but after several months was back in prison. Angela Burdett-Coutts went to visit her but Dickens suggested she was wasting her time: "Stonnell in prison, will always, I think be tolerably good. Out of it, until - perhaps - after great suffering, I have no hope of her."

Mary Ann wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts while in prison: "I take the liberty of writing a few lines to thank you for the kindness you have shown to such an unworthy creature as I have been to leave such a good home and I thank you taking the trouble you have to come and see me who am not worthy of such a kind benefactress I hope Madam that you will forgive me for I am very sorry for what I have done." Dickens refused to take her back and after she left prison she returned to a life of crime.

Miss Burdett-Coutts remained close to Charles Dickens. He kept her informed of the progress of his eldest son, Charles Culliford Dickens . He told her that Charley was "a child of a very uncommon capacity indeed" and that "his natural talent is quite remarkable". At this stage he was also convinced that "he takes after his father". Miss Burdett-Coutts, who had become Charley's unofficial godmother, offered to pay for his education and in January 1850, a week after Charley's thirteenth birthday, he left home to attend the top school in the country, Eton College. In June 1851 Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts: "I went down to Eton and saw Charley, who was very well indeed, and very anxious to be reported to you. He was much commended by his tutor, but had previously been reported rather lazy for the time being. I had therefore stopped his boat, and threatened other horrible penalties."

Angela Burdett-Coutts spent as much time as she could with the Duke of Wellington. In August 1851 he complained about the demands she was making: "It is absolutely impossible for me to call upon you this day! I wish that it could occasionally occur to your reflections that I am eighty-two not twenty-eight years of age. It would save you a good deal of disappointment and be less trouble for me." After his death in 1852 she bundled his letters together, tied them with strips of paper and sealed them with her own ring.

Charles Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts also felt strongly about the poor quality of working-class homes. Together they visited model buildings already in existence in Calthorpe Street off the Gray's Inn Road. Dickens was in favour of building flats as they took up less room than houses. Appalled at the "advancing army of bricks and mortar laying waste the country fields" he believed that if "large buildings had been erected for the working people, instead of the absurd and expensive separate walnut shells in which they live, London would have been about a third of its present size, and every family would have had a country walk, miles nearer to their work and would not have had to dine at public houses." He added that in flats "they would have had gas, water, drainage, and a variety of other humanizing things which you can't give them so well in little houses."

In 1851 they began planning the rebuilding of an area in the East End. Dickens suggested Bethnal Green, the area of London where Nancy, the prostitute in Oliver Twist, lived. He also encouraged her to consult with Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith, an authority on Public Health, who knew the area well. He also brought in his brother-in-law, Henry Austin, an experienced architect and sanitary engineer to advise in the early stages. Although the novelist followed its progress with interest, he does not appear to have had much to do with its later development.

Charles Dickens and Angela Burdett-Coutts both read accounts from Florence Nightingale about hospital conditions in Scutari during the Crimean War. Nightingale wrote about the "sodden misery in the hospital". On Dickens's advice, at the end of January 1855, she ordered from William Jeakes, an engineer working in Bloomsbury, a drying closet machine. It was built at a cost of £150. It was shipped out in parts and re-assembled in Istanbul. According to The Illustrated London News "1,000 articles of linen can be thoroughly dried in 25 minutes with the aid of Mr Jeakes centrifugal machine which took the wet out of the linen before it is placed in the drying closet." Dr Sutherland, who was working at the army hospital, wrote a letter of thanks to Jeakes: "The wet clothes give in as soon as they have seen it and dry up forthwith. The machine does great credit to Miss Coutt's philanthropy and also your engineering." Dickens commented that the machine was "the only solitary administrative thing, connected with the war that has been a success."

In May 1858, Catherine Dickens accidentally received a bracelet meant for Ellen Ternan. Her daughter, Kate Dickens, says her mother was distraught by the incident. Charles Dickens responded by a meeting with his solicitors. By the end of the month he negotiated a settlement where Catherine should have £400 a year and a carriage and the children would live with Dickens. Later, the children insisted they had been forced to live with their father.

Charles Culliford Dickens refused and decided that he would live with his mother. He told his father in a letter: "Don't suppose that in making my choice, I was actuated by any feeling of preference for my mother to you. God knows I love you dearly, and it will be a hard day for me when I have to part from you and the girls. But in doing as I have done, I hope I am doing my duty, and that you will understand it so."

Charles Dickens wrote to Miss Burdett-Coutts about his marriage to Catherine Dickens: "We have been virtually separated for a long time. We must put a wider space between us now, than can be found in one house... If the children loved her, or ever had loved her, this severance would have been a far easier thing than it is. But she has never attached one of them to herself, never played with them in their infancy, never attracted their confidence as they have grown older, never presented herself before them in the aspect of a mother."

Dickens claimed that Catherine's mother and her daughter Helen Hogarth had spread rumours about his relationship with Georgina Hogarth. Dickens insisted that Mrs Hogarth sign a statement withdrawing her claim that he had been involved in a sexual relationship with Georgina. In return, he would raise Catherine's annual income to £600. On 29th May, 1858, Mrs Hogarth and Helen Hogarth reluctantly put their names to a document which said in part: "Certain statements have been circulated that such differences are occasioned by circumstances deeply affecting the moral character of Mr. Dickens and compromising the reputation and good name of others, we solemnly declare that we now disbelieve such statements." They also promised not to take any legal action against Dickens.

On the signing of the settlement, Catherine found temporary accommodation in Brighton, with her son Charles Culliford Dickens. Later that year she moved to a house in Gloucester Crescent near Regent's Park. Dickens automatically got the right to take away 8 out of the 9 children from his wife (the eldest son who was over 21 was free to stay with his mother). Under the 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act, Catherine Dickens could only keep the children she had to charge him with adultery as well as bigamy, incest, sodomy or cruelty.

Charles Dickens now moved back to Tavistock House with Mamie Dickens, Georgina Hogarth, Kate Dickens, Walter Landor Dickens, Henry Fielding Dickens, Francis Jeffrey Dickens, Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson, Sydney Smith Haldimand and Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens. Mamie and Georgina were put in command of the servants and household management.

In June, 1858, Dickens decided to issue a statement to the press about the rumours involving him and two unnamed women (Ellen Ternan and Georgina Hogarth): "By some means, arising out of wickedness, or out of folly, or out of inconceivable wild chance, or out of all three, this trouble has been the occasion of misrepresentations, mostly grossly false, most monstrous, and most cruel - involving, not only me, but innocent persons dear to my heart... I most solemnly declare, then - and this I do both in my own name and in my wife's name - that all the lately whispered rumours touching the trouble, at which I have glanced, are abominably false. And whosoever repeats one of them after this denial, will lie as wilfully and as foully as it is possible for any false witness to lie, before heaven and earth."

Dickens also made reference to his problems with Catherine: "Some domestic trouble of mine, of long-standing, on which I will make no further remark than that it claims to be respected, as being of a sacredly private nature, has lately been brought to an arrangement, which involves no anger or ill-will of any kind, and the whole origin, progress, and surrounding circumstances of which have been, throughout, within the knowledge of my children. It is amicably composed, and its details have now to be forgotten by those concerned in it."

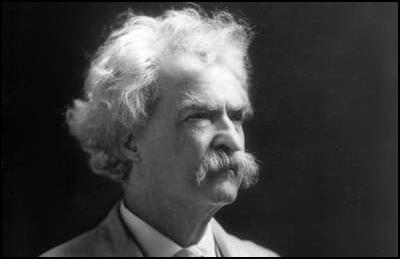

The statement was published in The Times and Household Words. However, Punch Magazine, edited by his great friend, Mark Lemon, refused, bringing an end to their long friendship. William Makepeace Thackeray also took the side of Catherine and he was also banned from the house. Dickens was so upset that he insisted that his daughters, Mamie Dickens and Kate Dickens, brought an end to their friendship with the children of Lemon and Thackeray.

Angela Burdett-Coutts, like Elizabeth Gaskell and William Makepeace Thackeray believed that publicizing his domestic problems was as bad as the separation itself. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was appalled by his behaviour: "What a crime, for a man to use his genius as a cudgel against his near kin, even against the woman he promised to protect tenderly with life and heart - taking advantage of his hold with the public to turn public opinion against her. I call it dreadful." Catherine Dickens wrote to Angela: "I have now - God help me - only one course to pursue. One day though not now I may be able to tell you how hardly I have been used." Angela later told a friend: "I knew Charles Dickens well, until after his separation from his wife - she I knew after that breach."

Miss Burdett-Coutts broke off contact with Dickens and she stopped funding Urania Cottage. It eventually closed down in 1862. Jane Rogers, the author of Dickens and Urania Cottage, the Home for Fallen Women (2003), has taken a close look at the women who stayed at Urania Cottage. She quotes one source that claimed: "Of these fifty-six cases, seven went away by their own desire during their probation; ten were sent away for misconduct in the home; seven ran away; three emigrated and relapsed on the passage out; thirty (of whom seven are now married) on their arrival in Australia or elsewhere, entered into good service, acquired a good character and have done so well ever since as to establish a strong prepossession in favour of others sent out from the same quarter."

In 1862 the model block of flats were opened at Columbia Square, Bethnal Green. The four blocks, each containing forty-five apartments, were so arranged that light and air could flow through free spaces at the corners on to which the windows of the corridors looked. There were some single rooms but most were family sets of two rooms. The living room contained a boiler and oven and was twelve feet by ten. The bedroom, in which the whole family slept, was twelve feet by eight. In Columbia Square gas and water were laid on and a resident superintendent and two porters kept the corridors and staircases clean. On the top floor there was a vast laundry and drying space.

On 22nd December 1878, Burdett-Coutts's devoted companion Hannah Brown died. She now began to rely on William Ashmead-Bartlett, her secretary. She had first encountered when he was a child and had paid for his education. At this time she was sixty-six and he was twenty-nine. She missed Hannah desperately and she wrote to Dudley Ryder, 2nd Earl of Harrowby: "If I have struggled through, it has been mainly if not solely through Mr Bartlett's being constantly there".

Stories began to circulate that Angela intended to marry Ashmead-Bartlett. Coutts Bank became concerned by this development. Senior members of the bank approached Queen Victoria about the proposed marriage. She refused to intervene directly but she did write to Angela's close friend, 2nd Earl of Harrowby, and commented: "The Queen knows too little respecting the subject to offer an opinion on it but it would grieve her much if Lady Burdett-Coutts were to sacrifice her high reputation and her happiness by an unsuitable marriage."

Dudley Ryder wrote to Burdett-Coutts, in an attempt to get her to change her mind. She replied that Ashmead-Bartlett had helped her greatly since the death of Hannah Brown, and she was frightened that this would be lost if she did not marry him as "this would not last, and to lose all this now leaves me a future from which I not only recoil but which I feel I cannot face." Another friend wrote: "She is like a girl of 15. She does not know the storm of censure, indignation, grief, amazement that is going on everywhere. She is quite unaware of what she is going to bring on herself."

Angela Burdett-Coutts married William Ashmead-Bartlett on 12th February 1881 at Christ Church, Mayfair, London. Now approaching her sixty-eighth year, she was attended by three bridesmaids and wore white velvet, veiled in delicate old lace. They spent their honeymoon at Ingleden House, Tenderden.

By marrying an alien she forfeited her right to her inheritance. Her sister, Clara Money, now became the major beneficiary. She was granted £16,000 a year but as she allowed herself a budget of £1,000 a month for household expenses. This left comparatively little for charities. Angela Burdett-Coutts also transferred most of her stocks and shares to her husband. A member of the Conservative Party, in 1885 he became MP for Westminster.

Baroness Angela Burdett-Coutts died on 30th December 1906 of acute bronchitis at her home in Stratton Street. Her body lay there in state for two days; nearly 30,000 paid their respects to a woman who had become known as the "Queen of the Poor".She was buried in Westminster Abbey on 5th January 1907.

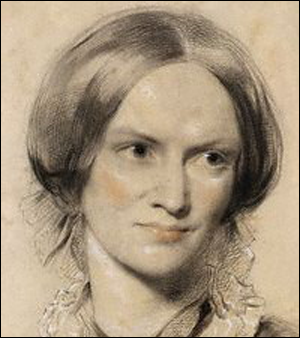

On this day in 1816 Charlotte Brontë, the daughter of Patrick Bronte and Mary Bronte, was born on 21st April 1816. When Charlotte was a small child, her father became curate in the village of Haworth. Charlotte's mother died in 1821, leaving five daughters and a son, to be looked after by an aunt, Elizabeth Branwell.

In 1824 Charlotte, and three of her sisters, was sent to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge. Conditions at the school were appalling and after two of her sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, died of consumption, Charlotte and Emily were brought home. For the next six years, the four surviving children, were left to look after themselves. They spent the time at Haworth telling and writing stories about fantasy worlds they had created.

Patrick Bronte decided in 1831 that Charlotte should continue her education and was sent to a Miss Wooler, who ran a school at Roe Head. This time she was treated well and while at the school made two life-long friends, Mary Taylor and Ellen Nussey.