On this day on 16th March

On this day in 1832 Michael Sadler makes a speech in the House of Commons on child labour. Sadler the MP for Newark introduced legislation that proposed limiting the hours of all persons under the age of 18 to ten hours a day. He argued: "The parents rouse them in the morning and receive them tired and exhausted after the day has closed; they see them droop and sicken, and, in many cases, become cripples and die, before they reach their prime; and they do all this, because they must otherwise starve. It is a mockery to contend that these parents have a choice. They choose the lesser evil, and reluctantly resign their offspring to the captivity and pollution of the mill."

The vast majority of the House of Commons were opposed to Sadler's proposal. However, in April 1832 it was agreed that there should be another parliamentary enquiry into child labour. Sadler was made chairman and for the next three months a parliamentary committee, that included John Cam Hobhouse, Charles Poulett Thompson, Robert Peel, Lord Morpeth, and Thomas Fowell Buxton interviewed 89 witnesses.

On 9th July Michael Sadler discovered that at least six of these workers had been sacked for giving evidence to the parliamentary committee. Sadler announced that this victimisation meant that he could no longer ask factory workers to be interviewed. He now concentrated on interviewing doctors who had experience treating people who worked in textile factories.

Sadler was one of the chief speakers at the meeting organised by Richard Oastler at York on 24th April 1832. Later that year 16,000 people assembled in Fixby Park, near Huddersfield, to thank him for his work on behalf of child workers.

In the 1832 General Election, Sadler's opponent was John Marshall, the Leeds flax-spinning magnate. Marshall used his considerable influence to win the election and Sadler was now without a seat in the House of Commons.

Sadler's report was published in January 1833. The information in the report shocked the British public and Parliament came under increasing pressure to protect the children working in factories. Lord Ashley, son and heir of the 6th Earl of Shaftesbury, agreed to take over from Sadler as the leader of the factory reform movement in Parliament.

On this day in 1872, Vernon Hartshorn was born at Cross Keys, Pontywaun, Monmouthshire, on 16th March 1872, the elder son of Theophilus Hartshorn, coalminer, and his wife, Helen Gregory, daughter of a farm labourer.

After being educated at a local school he worked as a miner at Risca before being employed as a clerk in a colliery company's office at Cardiff Docks. He later returned to the mine as a checkweighman (a representative elected by coal miners to check the findings of the mine owner's weighman where miners are paid by the weight of coal mined). In 1899 he married Mary Matilda, daughter of Edward Winsor, a Somerset coalminer. They had two sons and a daughter.

Hartshorn, who was a Primitive Methodist, joined the Independent Labour Party. In 1905 he was elected miners' agent of the Maesteg district of the South Wales Miners' Federation. In the 1910 General Election Hartshorn was the unsuccessful ILP candidate for Mid-Glamorgan. The following year he was elected to its executive council and to the national executive council of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain. As his biographer, W. L. Cook, has pointed out: "Harshorn... was one of a number of young radicals who displaced more established figures, following the Cambrian combine strike of 1910–11. He took a leading part in the minimum wage strike of 1912 and was prominent in local government business."

During the First World War, Hartshorn supported the war effort and served on the coal trade organization committee, the coal controllers' advisory committee, and the industrial unrest committee in South Wales. His loyal support resulted in him being awarded the OBE in 1918. As Herbert Tracey has pointed out: "A new spirit of insurgence, aggravated by the spectacle of gross profiteering, manifested itself, and, outrunning the tactics of the official leaders, kept affairs in a state of constant turmoil. Hartshorn, for one, had deliberately sacrificed much of his ascendancy through his steady adherence to a national line of conduct. It was not difficult to foment distrust of a man who had been made an OBE, and during the latter part of the war and the first year or so subsequently Vernon Hartshorn saw the rebellion against his leadership become formidable."

In the 1918 General Election, was returned unopposed as the first member for the newly formed Ogmore division of Glamorgan. In 1920 Hartshorn resigned from the national executive council of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain because of a a disagreement over the tactics employed in the strike. He returned in 1922 after being elected president of the South Wales Miners' Federation.

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". Ramsay MacDonald agreed to head a minority government, and therefore became the first member of the party to become Prime Minister. MacDonald had the problem of forming a Cabinet with colleagues who had little, or no administrative experience. MacDonald's appointments included Vernon Hartshorn as Postmaster General.

In October 1924 the MI5 intercepted a letter written by Grigory Zinoviev, chairman of the Comintern in the Soviet Union. The Zinoviev Letter urged British communists to promote revolution through acts of sedition. Vernon Kell, head of MI5 and Sir Basil Thomson head of Special Branch, told MacDonald that they were convinced that the letter was genuine. It was agreed that the letter should be kept secret but someone leaked news of the letter to the Times and the Daily Mail. The letter was published in these newspapers four days before the 1924 General Election and contributed to the defeat of MacDonald. The Conservatives won 412 seats and formed the next government. With his 151 Labour MPs, MacDonald became leader of the opposition in the House of Commons.

In 1927 Vernon Hartshorn. was appointed to the seven-man Indian Statutory Commission, chaired by, Sir John Simon. In the 1929 General Election the Labour Party won 288 seats, making it the largest party in the House of Commons. Ramsay MacDonald became Prime Minister again, but as before, he still had to rely on the support of the Liberals to hold onto power. MacDonald announced that a place for Hartshorn would be found as soon as the commission had completed its work and in 1930 he was appointed lord privy seal with special responsibility for the government's policy on employment. Hartshorn remained in the government until his death at Hill Crest, Maesteg, Glamorgan, on 13th March 1931.

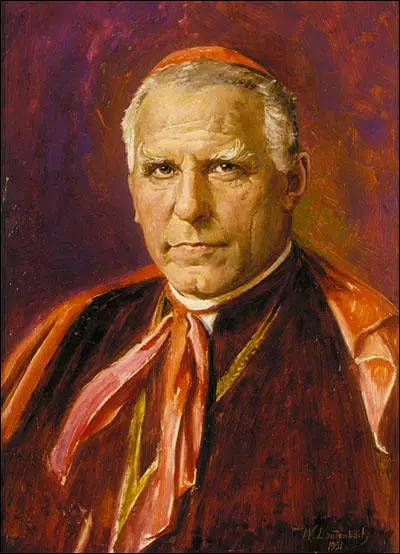

On this day in 1878 August von Galen, eleventh of thirteen children and the son of Count Ferdinand Heribert von Galen and Elisabeth von Spee, was born in Dinklage Castle in Germany. His father was a member of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) and a member of the Reichstag. He was a member of one of Germany's oldest families. The family also had a tradition of sending its sons into the Church.

Galen was educated by Jesuits before going on to study philosophy in Switzerland, where he decided to become a priest. He studied theology in both Innsbruck and Münster before being ordained a priest in Münster Cathedral on 28th May 1904. He then went on to serve in several parishes in Berlin.

During the First World War, von Galen volunteered for military service in order to demonstrate his loyalty to the Kaiser Wilhelm II. As parish priest, he encouraged his parishioners to serve their country willingly. In August 1917 he visited the front lines in France and found the optimistic morale of the troops uplifting. "Feelings of German nationalism, apparently, could triumph over concern for the violations of the sanctity of human life in war."

In 1917 he made statements urging the military to colonize Eastern Europe with German Catholics. Following the German surrender in November 1918, von Galen, warned of the dangers of establishing a republic, fearing that the masses would embrace left-wing ideas. A strong opponent of the Russian Revolution he believed that "the revolutionary ideas of 1918 had caused considerable damage to Catholic Christianity."

August von Galen was highly critical of the Catholic Centre Party (BVP) during the 1920s considering it too left-wing. Von Galen openly supported the Protestant Paul von Hindenburg against the Catholic candidate Wilhelm Marx in the presidential elections of 1925. He supported Adolf Hitler and criticised those religious figures who were quick to attack the new government. Von Galen spoke against those scholars who had criticised the Nazi government and called for "a just and objective evaluation of Hitler's new political movement".

Michael von Faulhaber, the Archbishop of Munich, was another who supported Hitler. After visiting Pope Pius XI he made the following statement: "After my recent experience in Rome in the highest circles, which I cannot reveal here, I must say that I found, despite everything, a greater tolerance with regard to the new government... Let us meditate on the words of the Holy Father, who in a consistory, without mentioning his name, indicated before the whole world in Adolf Hitler the statesmen who first, after the Pope himself, has raised his voice against Bolshevism."

On 24th April, 1933, it was reported "that Cardinal Faulhaber had issued an order to the clergy to support the new regime in which he (Faulhaber) had confidence". In the first few months of the new government no Church leaders spoke against the persecution of the Jews. The Concordat between the Nazis and the Catholic Church was signed in July 1933. It gave them the right to hold Catholic services and provided protection for its other organisations such as schools, youth groups and newspapers. However, there was a clause in the agreement that said "Catholic clerics who hold an ecclesiastical office in Germany or who exercise pastoral or educational functions must be a German citizen." The reason for this is that with the rapid rise in anti-semitism in Germany, some Jews had joined the Catholic Church for protection.

Von Galen was appointed Bishop of Münster in September 1933. It was not long before he began complaining to Hitler about violations of the Concordat. This included a rejection of the proposed changes to the school curriculum. By the beginning of 1934 von Galen had already delivered sermons condemning both Nazi racial policies and their behaviour towards the Catholic Church.

Bishop von Galen also attacked the writings of Alfred Rosenberg. In his book, The Myth of the Twentieth Century, Rosenberg had claimed that Catholicism was the "creation of Jewish clericalism". Von Galen responded by claiming that Rosenberg's book illustrated that "there are heathens again in Germany." Joseph Goebbels and his Ministry of Propaganda, tried to influence the debate by "releasing a flood of accusations against Catholic organizations for financial corruption."

Despite this he retained his nationalistic views and in 1936 he blessed the troops before they marched into the Rhineland. In 1937 Bishop August von Galen, Michael von Faulhaber, the Archbishop of Munich and Konrad von Preysing, Bishop of Eichstätt, helped draft the Pope's anti-Nazi encyclical Mit brennender Sorge (With Burning Concern). The encyclical addressed the problems being experienced by German Catholics and detailed the Pope's grave concerns about the way the Nazi government had ignored the terms of the Concordat of 1933.

Bishop von Galen welcomed Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 that heralded the war against the Soviet Union. However, soon afterwards he received confirmation from Kurt Gerstein of the Nazi government's euthanasia program directed at the mentally ill. Pope Pius XI had already issued a statement that: "The direct killing of an innocent person because of mental or physical defects is not allowed".

On 3rd August, 1941, August von Galen spoke out in a sermon against the Nazi practice of euthanasia: "If the principle that man is entitled to kill his unproductive fellow man is established and applied, then woe to all of us when we become aged and infirm! Then no man will be safe: some committee or other will be able to put him on the list of 'unproductive' persons, who in their judgment have become 'unworthy to live'. And there will be no police to protect him, no court to avenge his murder and bring his murderers to justice. Who could then have any confidence in a doctor? He might report a patient as unproductive and then be given instructions to kill him! It does not bear thinking of, the moral depravity, the universal mistrust, which will spread even in the bosom of the family, if this terrible doctrine is tolerated, accepted and put into practice. Woe to mankind! Woe to our German people, if the divine commandment 'Thou shalt not kill', which the Lord proclaimed on Sinai amid thunder and lightning, which God our Creator wrote into man's conscience from the beginning, if this commandment is not merely violated but the violation is tolerated and remains unpunished!"

It was reported that one woman who had attended the sermon hurried home to guard her elderly mother in case the Gestapo took her away to be murdered. Other people refused to undergo x-rays because they feared it was connected to the euthanasia programme. Details of the sermon were sent out of the country. The BBC made broadcasts concerning it and the RAF dropped copies of it over Germany.

Brishop Galen also attacked the Gestapo habit of seizing Church buildings and converting them to their own uses - which included cinemas and even brothels. The contents of these sermons were printed and distributed throughout the country. Adolf Hitler wanted Galen arrested but Joseph Goebbels warned against this as Galen was a popular religious leader.

Hitler accepted that it was not a good idea to make martyrs of well-known Church leaders. However, people who were caught with copies of the sermon, or who discussed it with colleagues, were arrested and sent to concentration camps. Richard Grunberger, the author of A Social History of the Third Reich (1971) has pointed out: "the regime took no action against Galen, but significantly, executed three Catholic priests at Lübeck who had distributed the text of Galen's sermon among soldiers."

Bishop August von Galen did not give anymore sermons against the Nazi government. In September 1941, he stated publicly that "We Christians do not make revolution". Hitler did not bring a halt to the programme. Instead he changed his strategy. "Thenceforth, patients would be killed by starvation and lethal medication in a larger number of extermination centres located within several asylums. This would be easier to conceal than the sudden removal and simultaneous disappearance of big groups of people."

Although he had decided not to play any part in the resistance to Hitler his sermons did inspire others. A copy arrived at the home of Robert Scholl. Two of his children, Hans Scholl and Sophie Scholl, organized the White Rose group. They joined forces with Christoph Probst, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf and Jugen Wittenstein and began distributing anti-nazi leaflets in Munich. They were caught and executed in April 1943.

On 20th July, 1944, Claus von Stauffenberg attempted to kill Hitler. Over the next few weeks following the July Plot several people including Wilhelm Canaris, Carl Goerdeler, Julius Leber, Ulrich Hassell, Hans Oster, Peter von Wartenburg, Henning von Tresckow, Ludwig Beck, Erwin von Witzleben and Erich Fromm were either executed or committed suicide.

Bishop August von Galen was suspected of being involved in some way with this attempt to overthrow the Nazi government and he was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. He was released early in 1945 and returned to Münster. In March he drove out to meet the Allies and surrendered the city. Joseph Goebbels recorded in his diary: "Bishop Galen of Münster has been interviewed by American journalists. Unexpectedly he attacked our Anglo-American enemies and their air terror. He is also afraid of the increasing Bolshevisation of Germany. Mr Bishop ought to have thought of this earlier. When we were giving warnings against Bolshevisation he was always on the other side. He is a chameleon, or rather a Westphalian blockhead who always says the opposite of what public opinion thinks."

On 13th April 1945, he criticised the behaviour of the occupying troops. He claimed that members of Red Army had raped German women and that soldiers in the British Army and the United States Army had stolen property belonging to the German population. He also accused the authorities of being indifferent to the suffering of the German people. Cardinal August von Galen died on 22nd March, 1946.

On this day in 1968 My Lai Massacre takes place. In 1971, Colonel Robert Heini reported that: "By every conceivable indicator, our army that now remains in Vietnam is in a state approaching collapse with individual units avoiding or having refused combat, murdering their officers and non-commissioned officers, drug-ridden and dispirited where not near-mutinous."

For sometime stories had been circulating about deteriorating behaviour amongst US soldiers. Efforts were made by the US army to suppress information about the raping and killing of Vietnamese civilians but eventually, after considerable pressure from certain newspapers, it was decided to put Lieutenant William Calley on trial for war-crimes. In March, 1971, Calley was found guilty of murdering 109 Vietnamese civilians at My Lai. He was sentenced to life imprisonment but he only served three years before being released from prison.

During the war, twenty-five US soldiers were charged with war-crimes but William Calley was the only one found guilty of the offence. Calley received considerable sympathy from the American public when he stated: "When my troops were getting massacred and mauled by an enemy I couldn't see, I couldn't feel, I couldn't touch... nobody in the military system ever described them anything other than Communists." Even Seymour Hersh, the reporter who had first published details of the My Lai killings, admitted that Calley was "as much a victim as the people he shot."

Critics of the war argued that as the US government totally disregarded the welfare of Vietnamese civilians when it ordered the use of weapons such as napalm and agent orange, it was hypocritical to charge individual soldiers with war-crimes. As the mother of one of the soldiers accused of killing civilians at My Lai asserted: "I sent them (the US army) a good boy, and they made him a murderer."

Philip Caputo, another US marine accused of killing innocent civilians, wrote later that it was the nature of the war that resulted in so many war-crimes being committed: "In a guerrilla war, the line between legitimate and illegitimate killing is blurred. The policies of free-fire zones, in which a soldier is permitted to shoot at any human target, armed or unarmed... further confuse the righting man's moral senses."

The publicity surrounding the My Lai massacre proved to be an important turning point in American public opinion. It illustrated the deterioration that was taking place in the behaviour of the US troops and undermined the moral argument about the need to save Vietnam from the "evils of communism". Vietnam was not only being destroyed in order to "save it" but it was becoming clear that those responsible for defeating communism were being severely damaged by their experiences.

On this day in 1971 Thomas E. Dewey died. Dewey was born in Owosso, Michigan, on 24th March, 1902. After graduating from Columbia University in 1925 he practised law in New York.

In 1933 Dewey he was appointed as the attorney of the southern district of New York. Fiorello La Guardia, the new mayor of New York, instructed Dewey to investigate Dutch Schultz, a man he believed was behind a large amount of crime in the city. When Schultz heard the news, he began making plans to have Dewey assassinated. This worried other gang leaders as they knew that this would only increase La Guardia's determination to wipe out New York gangsterism. In October 1935, Louis Lepke Buchalter, one of New York's main gang leaders, paid to gangsters, Charlie Workman and Emmanuel Weiss to kill Schultz.

Over a four year period Dewey obtained 72 convictions out of 73 prosecutions of leading criminals. Elected district attorney of New York County in 1937, he became the Republican Party candidate for governor and won the post in 1942.

In office he earned a reputation for efficiency and honesty and in 1944 he was chosen as presidential candidate against Franklin D. Roosevelt. The election took place during the Second World War and Dewey had an impossible task against a popular wartime leader and was beaten by 25,602,505 to 12,006,278.

In 1948 Dewey was once again the Republican Party parliamentary candidate and was expected to defeat the Democratic Party candidate, Harry Truman. The situation was confused by the decision of Henry Wallace to stand for the Progressive Party. Dewey played safe and waged a non-committal campaign designed to avoid offending any segment of the electorate. This was probably a mistake and Truman won by 24,105,812 to 21,970,065.

Dewey did not stand in 1952 and instead helped Dwight Eisenhower to win the Republican Party nomination and then the presidential election. At the end of his third term as governor of New York in 1955, Dewey retired from politics and returned to his law practice.

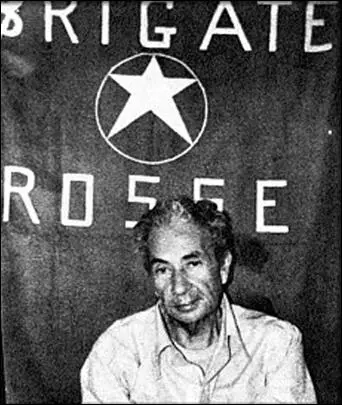

On this day in 1978 Italian prime minister Aldo Moro was kidnapped after left-wing Red Brigade gunmen ambushed his car killing his chauffeur and five policemen. They demanded the release of 13 Red Brigade members on trial in Turin. President Giulio Andreotti refused to negotiate with the kidnappers and on 9th May, 1978, Moro's dead body was found in the boot of a Renault car in central Rome.