On this day on 9th September

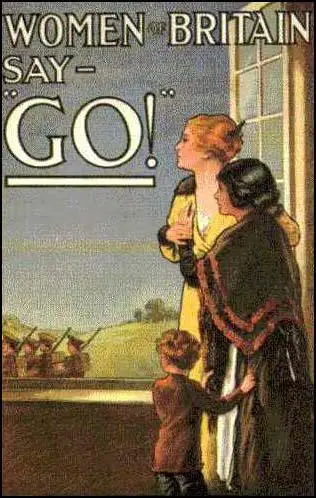

On this day in 1914 The Manchester Guardian reports on a speech made on recruitment by Christabel Pankhurst.

Miss Christabel Pankhurst celebrated her return tonight by addressing a big meeting in the London Opera House and making a sound recruiting speech. There could not have been more amazing proof of the complete change brought about by the war than the use by Miss Pankhurst of such phrases as the following:

"In the English-speaking countries under the British flag and the Stars and Stripes women's influence is higher. She has a greater political radius, her political rights are more extended than in any other part of the world. I agree with the Prime Minister that we cannot stand by and see brutality triumph over freedom."

This last remark startled her followers into laughter such as greets a particularly bold piece of repartee.

Miss Pankhurst occasionally fell, as if by force of habit, into the sarcastic vein, and then her followers felt they were on familiar ground.

It was obvious that the Christabel Pankhurst who has come back radiant from exile is not quite the same lady as she who fled to France so long ago. For one thing she seemed to have lost a good deal of her fluency of speech; for another the whole tone and temper of her speech were so entirely different, and there seemed to be no more reason that it should have been made on a Women's Social and Political Union platform than on any other. The anger and indignation which used to be turned against the Government she now directed against Germany, for in Germany she thinks women's position is the lowest and most hopeless. She ended with a vigorous appeal to the men to go and join the army, her argument being that militant women ought to be able to do something to rouse the militant men.

She had a most affectionate welcome appearing alone on the huge stage with an olive green curtain as the background and a barrier of bouquets at her feet.

Her mother was present in one of the boxes. The flags of the Allies decorated the room, and a women's band played national airs.

On this day in 1934 artist and critic Roger Fry died. He had broken his pelvis in a fall two days earlier. He was taken to the Royal Free Hospital but died later following a heart-attack. Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary: "I feel dazed; very wooden... My head all stiff. I think the poverty of life now is what comes to me; and this blackish veil over everything."

Roger Eliot Fry, the fifth of the nine children of Sir Edward Fry (1827–1918), and his wife, Mariabella Hodgkin (1833–1930), was born on 14th December 1866 at Highgate. His father was a descendant of Joseph Fry, who established J S Fry & Sons. The family were also members of the Society of Friends.

Fry was initially educated at home but later became a student at Clifton College (1877-1881). He achieved good results and won a science exhibition at King's College in 1884. The following year he began studying natural sciences.

While at the University of Cambridge he developed a strong bond with Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, a young political science lecturer. He also began to take an interest in the writings of John Ruskin. His interest in political philosophy brought him into contact with Edward Carpenter and George Bernard Shaw.

Roger Fry left university in 1889 and moved to London where he trained as an artist under Francis Bate. In 1891 he made his first trip to Italy and studied briefly at the Académie Julian in Paris, where he discovered the Impressionists. During this period he experimented with several different styles. He married the artist, Helen Coombe, the daughter of a corn merchant, on 3rd December 1896. She gave birth to a son, Julian (1901) and daughter Pamela (1902).

Robert Trevelyan, an art collector, began buying Fry's work. Trevelyan told Paul Nash that "Fry was without doubt the high priest of art of the day, and could and did make artistic reputations overnight." Soon afterwards he became a tutor at the Slade Art School. His students included C.R.W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, John S. Currie, Dora Carrington, Dorothy Brett, Maxwell Gordon Lightfoot, Edward Wadsworth, Adrian Allinson and Rudolph Ihlee.

Fry met Clive Bell in a railway carriage between Cambridge and London. His sister-in-law, Virginia Woolf, later recalled: "It must have been in 1910 I suppose that Clive one evening rushed upstairs in a state of the highest excitement. He had just had one of the most interesting conversations of his life. It was with Roger Fry. They had been discussing the theory of art for hours. He thought Roger Fry the most interesting person he had met since Cambridge days. So Roger appeared. He appeared, I seem to think, in a large ulster coat, every pocket of which was stuffed with a book, a paint box or something intriguing; special tips which he had bought from a little man in a back street; he had canvases under his arms; his hair flew; his eyes glowed."

Fry also became an important member of the Bloomsbury Group, that met to discuss literary and artistic issues. Virginia Woolf commented that "he had more knowledge and experience than the rest of us put together". Other members of the group included Vanessa Bell, Clive Bell, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Duncan Grant, Lytton Strachey, Vita Sackville-West, Ottoline Morrell, Bertram Russell, Leonard Woolf, David Garnett, Desmond MacCarthy and Arthur Waley.

Roger Fry took a keen interest in all forms of art. In May 1910 he wrote an article for The Burlington Magazine on drawings by African Bushman, where he praised their sharpness of perception and intelligence of design. David Boyd Haycock argued that "Fry was opening up his awareness to a wider sphere of artistic expression, though it was not one that would win him many friends." Henry Tonks remarked to a friend: "Don't you think Fry might find something more interesting to write about than Bushmen."

Later that year Fry, Clive Bell and Desmond MacCarthy went to Paris and after visiting "Parisian dealers and private collectors, arranging an assortment of paintings to exhibit at the Grafton Galleries" in Mayfair. This included a selection of paintings by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, André Derain and Vincent Van Gogh. As the author of Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "Although some of these paintings were already twenty or even thirty years old - and four of the five major artists represented were dead - they were new to most Londoners." This exhibition had a marked impression on the work of Duncan Grant, Vanessa Bell and Spencer Gore.

Henry Tonks, one of Britain's leading artists and the most important teacher at the Slade Art School, told his students that although he could not prevent them visiting the Grafton Galleries, he could tell them "how very much better pleased he would be if we did not risk contamination but stayed away". The critic for The Pall Mall Gazette described the paintings as the "output of a lunatic asylum". Robert Ross of The Morning Post agreed claiming the "emotions of these painters... are of no interest except to the student of pathology and the specialist in abnormality". These comments were especially hurtful to Fry as his wife had recently been committed to an institution suffering from schizophrenia.

Paul Nash recalled that he saw Claude Phillips, the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, on leaving the exhibition, "threw down his catalogue upon the threshold of the Grafton Galleries and stamped on it." William Rothenstein also disliked Fry's post-impressionist exhibition. He wrote in his autobiography, Men and Memories (1932) that he feared that the excessive publicity that the exhibition received, would seduce younger artists from "more personal, more scrupulous work".

In the spring of 1911 Fry went on holiday to Turkey with Vanessa Bell and Clive Bell. During her stay Vanessa had a miscarriage and a mental breakdown. Virginia Woolf went out to help nurse her. She was also going through a period of depression. She wrote: "To be 29 and unmarried - to be a failure - childless - insane too, no writer." Both Vanessa and Virginia fell in love with Fry. That summer Vanessa began an affair with Fry. They tried to keep in secret from Virginia but on 18th January 1912, Vanessa wrote to Fry: "Virginia told me last night that she suspected me of having a liaison with you. She has been quick to suspect it, hasn't she?" Knowledge of the affair was a major influence on why Virginia decided to marry Leonard Woolf.

Fry selected paintings for the exhibition entitled "British, French and Russian Artists" that was held at the Grafton Galleries, between October 1912 and January 1913. Artists included in the exhibition included Fry, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Percy Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Wassily Kandinsky. According to David Boyd Haycock: "Fry's second exhibition was not as badly received as the first. The intervening two years had seen a number of avant-garde shows in London, highlighting the work of continental modernism, and the art world was suddenly awash with isms."

In 1913 Fry joined with Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant to form the Omega Workshops. Other artists involved included Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Edward Wadsworth, Percy Wyndham Lewis and Frederick Etchells. Fry's biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau has suggested that: "It was an ideal platform for experimentation in abstract design, and for cross-fertilization between fine and applied arts."

Gretchen Gerzina has argued: "The Omega Workshops were the scene for some interesting - and sometimes volatile - conjunctions of personality and ideas. Their aim was to make art, through decoration, part of everyday life, and to provide both a workplace and an income for talented but hungry artists. Roger Fry had started the Omega in 1913 with these aims in mind and when it closed in 1919, he had substantially achieved them, despite commercial failure. The two Post-Impressionist Exhibitions which preceded its opening had given the artists a sense of imaginative freedom which canvas painting could not always express. Whole rooms, and all the objects within them, became their canvasses as they turned their brushes to textiles, dishes, screens, furniture and walls."

The art critic, Richard Cork, has pointed out: "He (Percy Wyndham Lewis) executed a painted screen, some lampshade designs, and studies for rugs, but his dissatisfaction with the Omega soon erupted into antagonism. No longer willing to be dominated by Fry, Lewis abruptly left the Omega with Edward Wadsworth, Cuthbert Hamilton, and Frederick Etchells in October 1913. By the end of the year he had begun to define an alternative to Fry's exclusive concentration on modern French art." This new movement became known as Vorticism.

Fry continued as a member of the Bloomsbury Group. One of its new members, Frances Partridge, later recalled in her autobiography, Memories (1981): "They were not a group, but a number of very different individuals, who shared certain attitudes to life, and happened to be friends or lovers. To say they were unconventional suggests deliberate flouting of rules; it was rather that they were quite uninterested in conventions, but passionately in ideas. Generally speaking they were left-wing, atheists, pacifists in the First World War, lovers of the arts and travel, avid readers, Francophiles. Apart from the various occupations such as writing, painting, economics, which they pursued with dedication, what they enjoyed most was talk - talk of every description, from the most abstract to the most hilariously ribald and profane."

Virginia Woolf commented that Fry was the "flesh and blood" of the group. With Fry about there was "always some new idea afoot... there was always some new picture standing on a chair to be looked at, some new poet fished out of obscurity and stood in the light of day." David Boyd Haycock, the author of A Crisis of Brilliance (2009) has pointed out: "It was a thrilling moment, the coming together of a circle of glittering talents who would help to refashion England's literary and artistic culture for the next forty years, dragging it all too reluctantly into the voguish world of the Modern." Hermione Lee argued in her book, Virginia Woolf (1996) that "Fry's arrival changed Bloomsbury, culturally and emotionally - to use one of his favourite words - in its texture."

Fry had a tremendous influence on the development of Virginia Woolf. She said she would have dedicated To the Lighthouse (1927) to Fry if she "had thought it was good enough." In a letter to Fry after its publication Woolf pointed out, "besides all your surpassing private virtues, you have I think kept me on the right path, so far as writing goes, more than anyone."

According to his biographer, Anne-Pascale Bruneau: "Much to his regret, Fry was never in a position to support himself by painting, but he had an exceptional gift for criticism, and was to be remembered as an enthralling lecturer, with a deep, mellifluous voice.... The venues were varied, including local art societies as well as university lecture halls; later, during the 1930s, Fry repeatedly filled the 2000-seat auditorium of the Queen's Hall. His subjects ranged from the analysis of a specific artist or school to discussions of aesthetics and of the methods of art history." Frances Partridge commented: "Anyone who heard Roger Fry lecture on art must owe him an immense debt of pure pleasure, for he had the rare gift of conveying his own love for paintings, even when their attractions were not obvious, even when the slides were put in upside down."

Books by Fry included Vision and Design (1920), Transformations (1926), Cézanne (1927) and Henri Matisse (1930). It has been argued by Kenneth Clark, that Fry's lectures and books had by introducing post-impressionist painting, and a critical terminology to make sense of it, had done more than any other critic to draw British art into modernist styles.

Roger Fry broke his pelvis in a fall on the 7th September, 1934. He was taken to the Royal Free Hospital but died two days later following a heart-attack. Virginia Woolf wrote in her diary: "I feel dazed; very wooden... My head all stiff. I think the poverty of life now is what comes to me; and this blackish veil over everything."

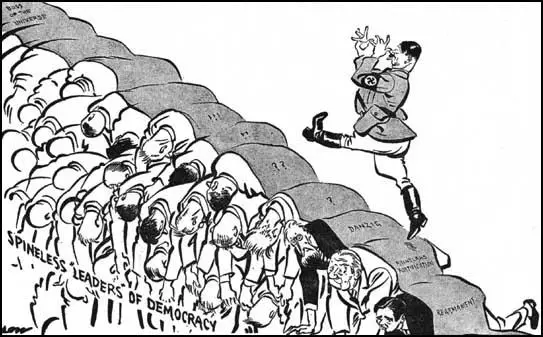

On this day in 1937 Percy Cudlipp, the editor of Evening Standard tells David Low to stop producing cartoons attacking Adolf Hitler. "The state of Europe is extremely tense at the present time. That being so, I don't want to publish anything in the Evening Standard which would add to the tension, or inflame tempers any more than they are already inflamed. There are people whose tempers are inflamed more by a cartoon than by any letterpress. So will you please, when you are planning your cartoons, bear in mind my anxiety on this score."

After the war it was revealed that in 1937 the German government asked the British government to have "discussions with the notorious Low" in an effort to "bring influence to bear on him" to stop his cartoons attacking appeasement. Lord Halifax, the foreign secretary, went to see Low: "When Lord Halifax visited Germany officially in 1937, he was told that the Führer was deeply offended by Low's cartoons of him, and that the paper in which they appeared, the Evening Standard, was banned in Germany.... On Halifax's return to London, he summoned Low and told him that his cartoons were impairing the prime minister's policy of appeasement."

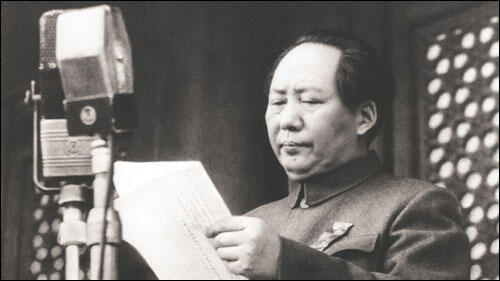

On this day in 1976 Mao Zedong died in Beijing.

Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-Tung), the son of a peasant farmer, was born in Chaochan, China, on 26th December 1893. He became a Marxist while working as a library assistant at Peking University and served in the revolutionary army during the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

Inspired by the Russian Revolution the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was established in Shanghai by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in June 1921. Early members included Mao, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De and Lin Biao. Following instructions from the Comintern members also joined the Kuomintang.

Over the next few years Mao, Zhu De and Zhou Enlai adapted the ideas of Lenin who had successfully achieved a revolution in Russia. They argued that in Asia it was important to concentrate on the countryside rather than the towns, in order to create a revolutionary elite.

Mao worked as a Kuomintang political organizer in Shanghai. With the help of advisers from the Soviet Union the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party) gradually increased its power in China. Its leader, Sun Yat-sen died on 12th March 1925. Chiang Kai-Shek emerged as the new leader of the Kuomintang. He now carried out a purge that eliminated the communists from the organization. Those communists who survived managed to established the Jiangxi Soviet.

The nationalists now imposed a blockade and Mao Zedong decided to evacuate the area and establish a new stronghold in the north-west of China. In October 1934 Mao, Lin Biao, Zhu De, and some 100,000 men and their dependents headed west through mountainous areas.

The marchers experienced terrible hardships. The most notable passages included the crossing of the suspension bridge over a deep gorge at Luting (May, 1935), travelling over the Tahsueh Shan mountains (August, 1935) and the swampland of Sikang (September, 1935).

The marchers covered about fifty miles a day and reached Shensi on 20th October 1935. It is estimated that only around 30,000 survived the 8,000-mile Long March.

When the Japanese Army invaded the heartland of China in 1937, Chiang Kai-Shek was forced to move his capital from Nanking to Chungking. He lost control of the coastal regions and most of the major cities to Japan. In an effort to beat the Japanese he agreed to collaborate with Mao Zedong and his communist army.

During the Second World War Mao's well-organized guerrilla forces were well led by Zhu De and Lin Biao. As soon as the Japanese surrendered, Communist forces began a war against the Nationalists led by Chaing Kai-Shek. The communists gradually gained control of the country and on 1st October, 1949, Mao announced the establishment of People's Republic of China.

In 1958 Mao announced the Great Leap Forward, an attempt to increase agricultural and industrial production. This reform programme included the establishment of large agricultural communes containing as many as 75,000 people. The communes ran their own collective farms and factories. Each family received a share of the profits and also had a small private plot of land. However, three years of floods and bad harvests severely damaged levels of production. The scheme was also hurt by the decision of the Soviet Union to withdraw its large number of technical experts working in the country. In 1962 Mao's reform programme came to an end and the country resorted to a more traditional form of economic production.

As a result of the failure on the Great Leap Forward, Mao retired from the post of chairman of the People's Republic of China. His place as head of state was taken by Liu Shaoqi. Mao remained important in determining overall policy. In the early 1960s Mao became highly critical of the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. He was for example appalled by the way Nikita Khrushchev backed down over the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Mao became openly involved in politics in 1966 when with Lin Biao he initiated the Cultural Revolution. On 3rd September, 1966, Lin Biao made a speech where he urged pupils in schools and colleges to criticize those party officials who had been influenced by the ideas of Nikita Khrushchev.

Mao was concerned by those party leaders such as Liu Shaoqi, who favoured the introduction of piecework, greater wage differentials and measures that sought to undermine collective farms and factories. In an attempt to dislodge those in power who favoured the Soviet model of communism, Mao galvanized students and young workers as his Red Guards to attack revisionists in the party. Mao told them the revolution was in danger and that they must do all they could to stop the emergence of a privileged class in China. He argued this is what had happened in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev.

Lin Biao compiled some of Mao's writings into the handbook, The Quotations of Chairman Mao, and arranged for a copy of what became known as the Little Red Book, to every Chinese citizen.

Zhou Enlai at first gave his support to the campaign but became concerned when fighting broke out between the Red Guards and the revisionists. In order to achieve peace at the end of 1966 he called for an end to these attacks on party officials. Mao remained in control of the Cultural Revolution and with the support of the army was able to oust the revisionists.

The Cultural Revolution came to an end when Liu Shaoqi resigned from all his posts on 13th October 1968. Lin Biao now became Mao's designated successor.

Mao now gave his support to the Gang of Four: Jiang Qing (Mao's fourth wife), Wang Hongwen, Yao Wenyuan and Zhange Chungqiao. These four radicals occupied powerful positions in the Politburo after the Tenth Party Congress of 1973.