Women and Recruitment

Women played an important role in persuading men to join the army. In August 1914, Admiral Charles Fitzgerald founded the Order of the White Feather. This organisation encouraged women to give out white feathers to young men who had not joined the army.

After war was declared, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) began negotiating with the British government. On the 10th August the government announced that it was releasing all suffragettes from prison. In return, the WSPU agreed to end their militant activities. Some leaders of the WSPU such as Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney played an important role as speakers at meetings to recruit young men into the army. Others like Sylvia Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence were opposed to the war and refused to carry out this role. These women used their efforts to bring an end to the war and played an active role in organisations such as the Women's Peace Party.

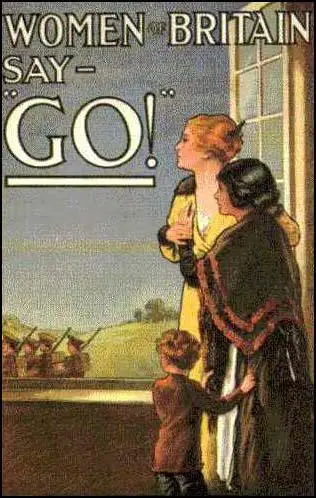

The British Army began publishing posters urging men to become soldiers. Some of these posters were aimed at women. One poster said: "Is your Best Boy wearing khaki? If not, don't you think he should be?" Another poster read: "If you cannot persuade him to answer his country's call and protect you now, discharge him as unfit."

The Mothers' Union also published a poster. It urged its members to tell their sons: "My boy, I don't want you to go, but if I were you I should go." The poster added: "On his return, hearts would beat high with thankfulness and pride."

Baroness Emma Orczy founded the Active Service League, an organisation that urged women to sign the following pledge: "At this hour of England's grave peril and desperate need I do hereby pledge myself most solemnly in the name of my King and Country to persuade every man I know to offer his services to the country, and I also pledge myself never to be seen in public with any man who, being in every way fit and free for service, has refused to respond to his country's call."

Primary Sources

(1) The Daily Telegraph (4th September, 1914)

After an absence from England of about two and a half years, spent mainly in Paris, Miss Christabel Pankhurst has returned. Speaking on behalf of the Women's Social and Political Union she said: "We feel the best thing we can do is to try and put the case to others as we women see it ourselves. The people of this country must be made to realise that this is a life and death struggle, and that the success of the Germans would be disastrous for the civilization of the world, let alone for the British Empire. Everything that we women have been fighting for and treasure would disappear in the event of a German victory."

(2) The Manchester Guardian (9th September, 1914).

Miss Christabel Pankhurst celebrated her return tonight by addressing a big meeting in the London Opera House and making a sound recruiting speech. There could not have been more amazing proof of the complete change brought about by the war than the use by Miss Pankhurst of such phrases as the following:

"In the English-speaking countries under the British flag and the Stars and Stripes women's influence is higher. She has a greater political radius, her political rights are more extended than in any other part of the world. I agree with the Prime Minister that we cannot stand by and see brutality triumph over freedom."

This last remark startled her followers into laughter such as greets a particularly bold piece of repartee.

Miss Pankhurst occasionally fell, as if by force of habit, into the sarcastic vein, and then her followers felt they were on familiar ground.

It was obvious that the Christabel Pankhurst who has come back radiant from exile is not quite the same lady as she who fled to France so long ago. For one thing she seemed to have lost a good deal of her fluency of speech; for another the whole tone and temper of her speech were so entirely different, and there seemed to be no more reason that it should have been made on a Women's Social and Political Union platform than on any other. The anger and indignation which used to be turned against the Government she now directed against Germany, for in Germany she thinks women's position is the lowest and most hopeless. She ended with a vigorous appeal to the men to go and join the army, her argument being that militant women ought to be able to do something to rouse the militant men.

She had a most affectionate welcome appearing alone on the huge stage with an olive green curtain as the background and a barrier of bouquets at her feet.

Her mother was present in one of the boxes. The flags of the Allies decorated the room, and a women's band played national airs.

(3) On 8th April 1916 Sylvia Pankhurst, organized a demonstration in London against conscription.

The militarists continued their agitation for "National Service" for all men and women "from 16-60 years of age," and a "Service Franchise" giving a vote to every soldier, sailor, and munition worker and disfranchising conscientious objectors. The women were to remain voteless till after the war.

We were to march from the East End to Trafalgar Square, to raise our opposing slogans:

"Complete democratic control of national and international affairs!" "Human suffrage and no infringement of popular liberties." The Daily Express, the Globe, and many other newspapers, wherein appeared frequent incitement to violence against "peace talk," directed their battalions of invective against our meeting, denouncing it as "open sedition." As usual, friends saluted us on our march through the East End; crowds gathered to speed us; they had struggled with us for a decade; they supported us still, though our standard seemed now more Utopian, more elusively remote.

At Charing Cross we came into a great concourse of people, clapping and cheering. They welcomed our slender ranks as an expression of the old, old cry: "Not might, but rights' - a symbol of the triumph of the spirit over sordid materialism, and of their own often frustrated hopes and long unsatisfied desires. To them we were protestants against their sorrows, and true believers in the living possibility of a world of happiness. In their jolly kindness some shouted: "Good old Sylvia!" I gave my hands to many a rough grip. They pressed round me, ardent and gay, sorrowful, hopeful, earnest. Many a woman's eyes brimmed with tears as she met mine; I knew, by a sure instinct, that she had come across London, overweighted with grief, to ease her burden by some words with me.

As we entered the square a rush of friends, with a roar of cheers and a swiftness which forestalled any hostile approach, bore us forward, and hoisted a group of us on the east plinth, facing the Strand, whilst the banner-bearers marched on westward, where the banners were to be handed up; but the north side was packed with soldiers who fell upon the approaching banners and tore them to shreds. The law offered no protection; so few policemen had never been seen in the square at any demonstration. Far from assisting us to maintain order, they prevented our men speakers, and numbers of our members who wished to support us, from mounting the plinth, though we urged that they should come. We were left, a little group of women and a child or two, to deal with what might arise.

The Government had obviously given orders to leave us to the violence of the mob.

We were not afraid.

A small, hostile group had established itself by the plinth, prompted by the organisers of the disturbance, whom I recognised as old hands at such work; poor, shabby public house loafers, they shouted without pausing for breath till their red faces were purple. I continued in spite of them, by taking pains to speak clearly and not too fast. From the north the disturbers hurled at me roughly screwed balls of paper, filled with red and yellow ochre, which came flying across the lions' backs and broke with a shower of colour on anyone they chanced to hit. The reporters on the plinth had drawn near me to listen; thus, inadvertently, they intercepted the missiles aimed at me, and were covered with red and yellow.

They sprang back to avoid a further volley, and Mrs. Drake's twelve-year-old daughter, Ruby, received a deluge of red full in her eyes. Crying, she buried her face in her mother's dress, while the "patriots" raised a cheer.

Always after such incidents, our mother and baby clinics, the day nursery, the restaurants, the factory, all our work for ameliorating distress suffered immediately from loss of donations. A cable repudiating me from Mrs. Pankhurst was published and helped to detach some of the old W.S.P.U. members who still supported us.