On this day on 8th June

On this day in 1860 The Times writes an article on the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. "A meeting of the Society for Promoting the Employment of Women, in connexion with the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, was held at 19, Langham-place on the evening of Friday, June 29. Lord Shaftesbury took the chair at 9 o'clock, by which time a numerous and influential audience had assembled. The chairman, in an opening address, explained and enforced the principles of the society, congratulated the members on the success which has attended their efforts during the first year, and enforced the necessity of still further extending their operations. Mr. Cookson urged law engrossing as a suitable occupation for women, described the office established by the society, which is already supported by several solicitors, and gave an interesting account of the work done there. Mr. Hastings spoke of printing as particularly well adapted to women, and read a paper contributed by Miss Emily Faithfull, on the introduction of women to the printing trade. Mr. Mackenzie read a paper by Miss J. Boucherett on bookkeeping, stating that a want of knowledge of accounts was one great reason of the disinclination to employ women in shops, showing how they might be better fitted for the offices of cashiers and bookkeepers, and announcing that a school to supply these deficiencies had been opened by the society. Vice-Chancellor Wood spoke of the other occupations for women, and recommended that they should be employed as clerks in post-offices, and as managers in hotels, as hairdressers, &c. He read a paper by Miss Parkes on the same subject, and concluded with an eloquent appeal for further subscriptions. The audience were then introduced into a lower room, where the interesting collection of women's work in law engrossing, printing, designing, &c., was exhibited, and excited much admiration."

The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women had been formed in 1859 by Emily Faithfull, Jessie Boucherett, Bessie Rayner Parkes and Barbara Bodichon. Faithfull's biographer, Felicity Hunt claims: "The group pressed for legal reform in women's status (including suffrage), explored new areas for women's employment, and campaigned for improved educational opportunities for girls and women. Emily Faithfull was at the heart of this multi-faceted campaign and identified with all three dimensions, although she is best known for her work in women's employment. Her public support of the enfranchisement of women developed later from her investigations and practical campaigns surrounding employment, but from the beginning she was actively involved in the successful movement led by Emily Davies to have the university local examinations opened to women."

On this day in 1903 Ralph Yarborough is born. Ralph Webster Yarborough, the seventh of nine children, was born in Chandler, Henderson County, Texas, on 8th June, 1903. After attending local schools he entered the West Point Military Academy in 1919 but dropped out the following year.

Yarborough was a school teacher in Henderson County for three years before moving to Germany where he was assistant secretary for the American Chamber of Commerce in Berlin. On his return he attended University of Texas Law School.

After graduating in 1927 he became a lawyer in El Paso. Over the next four years he won several cases against the Magnolia Petroleum Company and other major oil companies and successfully establishing the right of public schools and universities to oil-fund revenues. He also served as district judge in Austin (1936-41).

During the Second World War Yarborough, a member of the 97th Division, served in Europe and Japan. When he left the army in 1946 he had reached the rank of lieutenant colonel. After the war Yarborough became a lawyer in Austin, Texas.

A member of the Democratic Party Yarborough unsuccessfully challenged Governor Allan Shivers for the nomination in 1952 and 1954. Yarborough was one of the leaders of the progressive wing of the party. Shivers, on the right of the party, accused Yarborough of being in favour of racial integration and having support from the American Communist Party.

Yarborough, with the support of the trade unions, was elected to the United States Senate in April 1957. A left-wing member of the party, Yarborough was the only member of the Senate representing a former Confederate state to vote for every significant piece of civil rights legislation. This included the Civil Rights Act (1957) and Civil Rights Act (1960).

In the summer of 1963 President John F. Kennedy contacted Yarborough and asked him what could be done to help the image of the president in the state. Yarborough apparently told Kennedy “the best thing he could do was to bring Jackie to Texas and let all those women see her”. Kennedy had won Texas by only a small margin in the presidential election of 1960. It was believed that this victory was mainly due to the campaigning of his running-mate, Lyndon B. Johnson, who was the dominant political figure in Texas at the time. Kennedy believed that he needed to win Texas in 1964 if he was to be re-elected as president.

On 22nd November, 1963, President John F. Kennedy arrived in Dallas. It was decided that Kennedy and his party, including his wife, Jacqueline Kennedy, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Governor John Connally and Ralph Yarborough, would travel in a procession of cars through the business district of Dallas. A pilot car and several motorcycles rode ahead of the presidential limousine. As well as Kennedy the limousine included his wife, John Connally, his wife Nellie, Roy Kellerman, head of the Secret Service at the White House and the driver, William Greer. The next car carried eight Secret Service Agents. This was followed by a car containing Lyndon Johnson and Ralph Yarborough.

At about 12.30 p.m. the presidential limousine entered Elm Street. Soon afterwards shots rang out. John Kennedy was hit by bullets that hit him in the head and the left shoulder. Another bullet hit John Connally in the back. Ten seconds after the first shots had been fired the president's car accelerated off at high speed towards Parkland Memorial Hospital. Both men were carried into separate emergency rooms. Connally had wounds to his back, chest, wrist and thigh. Kennedy's injuries were far more serious. He had a massive wound to the head and at 1 p.m. he was declared dead.

Within two hours of the killing, a suspect, Lee Harvey Oswald, was arrested. Throughout the the time Oswald was in custody, he stuck to his story that he had not been involved in the assassination. On 24th November, while being transported by the Dallas police from the city to the county jail, Oswald was shot dead by Jack Ruby.

After the death of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Lyndon B. Johnson, was appointed president. Yarborough was a great supporter of Johnson's Great Society programs in education, environmental preservation, and health care. He also voted from the Civil Rights Act (1964)and the Voting Rights Act (1965). Yarborough was more critical of Johnson's foreign policy and was a strong opponent of the Vietnam War.

An advocate of preserving the environment, Ralph Yarborough sponsored the Endangered Species Act of 1969 and the legislation that established three national wildlife sanctuaries in Texas-Padre Island National Seashore (1962), Guadalupe Mountains National Park (1966), and Big Thicket National Preserve (1971).

Yarborough was a member of the Senate until he was defeated by Lloyd Bentsen in 1970. He now returned to work as a lawyer in Austin. He also served as a member of the State Library and Archives Commission of Texas 1983-1987.

Ralph Webster Yarborough died in Austin, Texas, on 27th January, 1996.

On this day in 1909 Mary Blathwayt writes about Elsie Howey. "Bristol. We were on a lorry and a large crowd of children were waiting for us when we arrived. Things were thrown at us all the time; but when we drove away at the end we were hit a great many times. Elsie Howey had her lip hit and it bled. I was hit by potatoes, stones, turf and dust. Something hit me very hard on my right ear as I was getting into our tram. Someone threw a big stone as big as a baby's head; it fell onto the lorry."

Elsie Howey, the daughter of Gertrude and Thomas Howey, rector of Finningley in Nottinghamshire, on 1st December 1884. She attended St Andrews University between 1902-1904. She lived for a while in Germany where she later claimed "she had first occasion to realise women's position."

Howey joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and in February 1908 she was arrested for taking part in a demonstration outside the House of Commons. She was sentenced to six weeks' imprisonment and released on 18th March.

In May 1908, she joined Mary Blathwayt and Annie Kenney to help at a by-election in Shropshire. Blathwayt wrote in her diary: "This afternoon I helped Annie Kenney make her plans for a West of England campaign, I wrote out lists of towns and dates which are to be sent to Mrs. Pankhurst and Mrs. Pethick Lawrence. This evening Miss Howey went round the town with some steps, and I went with her. And when we came to a crowd she got onto the steps and shouted Keep the Liberal out. Votes for Women".

Elsie Howey was arrested for the second time after taking part in a demonstration outside the home of Herbert Asquith. She was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. On her release she and Vera Wentworth were met at the gates of Holloway Prison and then drawn by 50 women on a carriage to Queen's Hall. On her arrival she was presented with bouquets in the suffragette colours and with illuminated scrolls designed by Sylvia Pankhurst to commemorate their imprisonment.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence wrote an article in Votes for Women in February 1909: "I say to you young women who have private means or whose parents are able and willing to support you while they give you freedom to choose your vocation. Come and give one year of your life to bringing the message of deliverance to thousands of your sisters... Miss Elsie Howey is honorary organiser in Plymouth. She is the daughter of Mrs. Howey, of Malvern. Mrs. Howey and her two daughters have given generously of all that they have, but the best prized gift is the life-work of this noble girl who has undergone two periods of imprisonment for the sake of women less privileged and happily placed than herself. She is one of our most able and successful organisers, and takes all the duties and responsibilities of our chief officers."

Elsie Howey, who was described by the mother of Mary Blathwayt as being "a wonderful speaker" went to work with Annie Kenney who was based in Bristol. During this period she was a visitor to Eagle House at Batheaston. Others who spent time at Blathwayt's house included Christabel Pankhurst, Clara Codd, Constance Lytton, Vera Wentworth, Jessie Kenney, Annie Kenney, Clare Mordan and Helen Watts. Colonel Linley Blathwayt photographed the women. These were then signed and sold at WSPU bazaars. He also invited them to plant a tree to commemorate their prison sentences and hunger strikes.

On 16th April 1909 Howey rode as Joan of Arc at the head of the procession to welcome Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence on her release from Holloway Prison. On 30th July she was arrested with Vera Wentworth for demonstrating at a meeting held in Penzance by Lord Carrington. They were sentenced to seven days' imprisonment and both women went on hunger strike. Howey fasted for 144 hours and on her release she went to stay at Eagle House at Batheaston.

On 5th September she was involved with Vera Wentworth and Jessie Kenney in assaulting Herbert Asquith and Herbert Gladstone while they were playing golf. Emily Blathwayt was horrified by this increase in violence. On 7th September she wrote in her diary: "We hear of terrible things by the two Hooligans we know, Vera and Elsie and there is a Kenney in it. They made a regular raid on Mr. Asquith breaking a window and using personal violence. Then missiles have been thrown lately through windows during Cabinet Members meetings which might injure or kill innocent persons."

The following day Emily Blathwayt sent a letter to the WSPU headquarters: "Dear Madam, with great reluctance I am writing to ask that my name may be taken off the list as a Member of the W.S.P.U. Society. When I signed the membership paper, I thoroughly approved of the methods then used. Since then there has been personal violence and stone throwing which might injure innocent people. When asked by acquaintances what I think of these things I am unable to say that I approve, and people of my village who have hitherto been full of admiration for the Suffragettes are now feeling very differently. Colonel Linley Blathwayt wrote to Christabel Pankhurst complaining about the behaviour of Elsie Howey and Vera Wentworth and suggested that they would no longer be welcome at Eagle House.

Colonel Blathwayt also wrote letters to Wentworth and Howley about their behaviour. He said that "an attack on one undefended man by three women was an act I did not expect from the Society". According to Emily Blathwayt, they received a "long letter from Vera Wentworth who is very sorry we are grieved but if Mr. Asquith will not receive deputation they will pummel him again." She also claimed that Herbert Gladstone gave Jessie Kenney "a nasty blow in the chest".

Howey was arrested with Constance Lytton on 14th January 1910 and sentenced to six weeks' hard labour. Votes for Women described Howey as: "A devoted honorary organiser who gives the whole of her services and the whole of her life to the Cause. She is a beautiful, refined, and charming girl."

Elsie Howey was inactive in 1911 but was arrested again in March 1912 when she took part in the WSPU window-smashing campaign. She was found guilty and sentenced to four months' imprisonment. At the end of 1912 she was back in Holloway Prison for setting-off a fire-alarm. She went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed. Elsa Gye commented that the injuries inflicted during the force-feeding meant that "her beautiful voice was quite ruined." In June 1913 Howey played the role of Joan of Arc at the funeral of Emily Wilding Davison.

Her biographer, Krista Cowman, wrote: "Tired and ill, Elsie vanished from public life when militancy ended in 1914. She remained in Malvern but followed no career, and never fully recovered from the sacrifices she made in the name of the WSPU. She died on 13 March 1963 at the Court House Nursing Home, Court Road, Malvern, from chronic pyloric stenosis, almost certainly connected to her numerous forcible feedings."

On this day in 1924 George Mallory died while returning from climbing Mount Everest.

George Leigh Mallory, the son of the clergyman, Herbert Mallory, was born in Mobberley on 18th June 1886. His younger brother was Trafford Leigh Mallory (1892-1944).

At the age of thirteen, Mallory won a mathematics scholarship to Winchester College. A few years later one of the teachers at the school introduced him to mountaineering. This included a trip to the Alps.

In 1905 Mallory went to Magdalene College, Cambridge, to study history. While at university he became friends with Geoffrey Winthrop Young, Rupert Brooke, John Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant and Lytton Strachey. After graduating Mallory became a teacher at Charterhouse where he taught Robert Graves, encouraging his interest in poetry and mountaineering. Graves later recalled: "He (Mallory) was wasted at Charterhouse. He tried to treat his class in a friendly way, which puzzled and offended them."

George Mallory met Ruth Turner at a dinner held by Arthur Clutton-Brock in 1913. The following year, her father, Hugh Thackeray Turner invited Mallory to join him and his three daughters on a family holiday in Venice. The couple fell in love after a trip to Asolo. Ruth wrote to George after she arrived back in England: "How wonderful it was that day among the flowers at Asolo!"

Ruth Turner became engaged to Mallory in April 1914. On 18th May George wrote to Ruth: "it's too too wonderful that you should love me and give me such happiness as I never dreamt of". Seven days later he was writing: "Oh! my arms are aching dear for you - to draw you swiftly and firmly close to me."

George told his brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, that he intended to marry Ruth. He replied: "This is good news indeed. I am very pleased to hear it; heartiest congratulations! I must say I was extraordinarily surprised. However I suppose the influence of spring and Italy, combined with meeting the right person, fairly laid you by the heals."

Mallory married Ruth Turner on 29th July 1914. Geoffrey Winthrop Young was the best-man. Her father, Hugh Thackeray Turner, provided her with an annual income of £750 and arranged for them to live in a house close to the family estate in Godalming. The couple went to Porlock in Somerset for their honeymoon.

Mallory was deeply shocked by the outbreak of the First World War. He believed strongly that international disputes should be solved by diplomacy. Some of his friends, including Geoffrey Winthrop Young and Duncan Grant, were pacifists. Young became a war correspondent with The Daily News and his reports of the slaughter on the Western Front appalled Mallory.

His brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, and two of his best friends, Robert Graves and Rupert Brooke, did join the British Army. Although opposed to the war, Mallory began to feel that he should do his duty and help the war effort. Geoffrey Winthrop Young resigned as a journalist and began to help to transport casualties and refugees away from the front-line. On 22nd November 1914 Mallory wrote to Young saying that it was "increasingly impossible to remain a comfortable schoolmaster". He added: "Naturally I want to avoid the army for Ruth's sake - but can't I do some job of your sort?"

On 9th December, 1914, the war minister, Lord Kitchener, instructed headteachers not to let teachers join up if this would impair the work of their schools. Frank Fletcher, the head of Charterhouse, used this directive to refuse permission for Mallory to join the armed forces. Mallory's guilt for not taking part in the war increased after hearing about the death of his friend, Rupert Brooke in April 1915.

The following month he received a letter from his brother, Trafford Leigh Mallory, who had just arrived at the front-line near Ypres. Despite the foul latrines and the smell of rotting bodies he told him that: "I must say I am extraordinarily happy here. I never thought I would enjoy it so much." However, within a few weeks of living in the trenches with having to deal with constant gas attacks his tone changed. "You have an alternative of putting your head down in the trench and being asphyxiated or putting it up over the trench into rapid fire. We have got gag things to put over our mouths, but still many seem to get killed."

On 16th June 1915 Leigh-Mallory was wounded in the leg during an attack on the German trenches at Ypres. As a result of the seriousness of his injury Leigh-Mallory was sent to a hospital in Oxford.

Ruth Mallory wrote to her husband on 10th August 1915: "I wonder dear how much we shall keep up with the times and be able to be proper companions for our children. Lets try and remember that they must educate us as well as we educating them then I think we may not go so far wrong, we mustn't hate every new thing that comes along until its got old." On 19th September 1915, Ruth gave birth to a girl who they named as Francis Clare. George had wanted a boy and he wrote to a friend: "I can't claim any great interest at present (in my daughter)."

Some of his favourite students joined the British Army. He wrote to a friend that losing them was "like cutting off buds". Mallory could no longer accept the idea that these young men should be fighting on his behalf and despite the protests of Frank Fletcher he decided to join the Royal Artillery. He wrote to a friend: "I feel so mixed up when I think of it - not wanting perfect safety for my own sake because I prefer adventure and want anyway to share those risks with my friends; but thinking so very differently where Ruth comes in. I'm afraid she'll feel very sore when I'm out there."

On 4th May 1916 Second Lieutenant George Mallory was sent to France. That night Ruth wrote to her husband: "I think I must write to you tonight it makes me feel less far from you. I am alright dear. I am cheerful and I have not cried anymore. I had baby as soon as I got home till she went to bed and it was very comforting. She is more of a comfort than anything else I could have." Mallory replied that her letters were like "great shafts of light which come pouring in on me".

George Mallory was assigned to the 40th Siege Battery, then position in the northern sector on the Western Front. That summer he took part in the Somme offensive. He wrote to his wife about the bombardment that took place before the infantry attack: "It was very noisy. Field batteries again firing over our heads (of course there are plenty in front of us too) and most annoying of them a 60-pounder which has a nasty trick of blowing out the lamp with its vigorous blast."

Mallory wrote that he was "full of hope" that the offensive would be successful. On 14th July 1916 he sent another letter to Ruth Mallory arguing that: "It really seems as though we have given the Hun something of a whacking and also that his reserves are pretty well used up. Shall we find suddenly one day that the war is over - finished as dramatically as it began?" A few days later he was writing that "our hope of moving forward immediately seemed to have vanished."

Later that month George Mallory saw flamethrowers in action for the first time. He described how he saw "a sort of liquid fire, a long line of trenches apparently on fire and exploding with great flashes and clouds of sparks."

On 15th August 1916 he wrote about the large number of people killed during the Somme Offensive; "I don't object to corpses so long as they are fresh... With the wounded it is different. It always distresses me to see the." As a member of the Royal Artillery he was less likely to be killed or wounded than in the infantry. He told his wife: "The chance of survival in my branch of the services is very large."

Mallory was constantly worried about the dangers of killing his own men. He wrote in a letter to his wife about this fear: "Before I went to sleep I heard distinctly from the murmur of voices in the tent some mention of our troops being shelled out of a trench by our own guns... I can't tell you what a miserable time I had after that. You see, if my registration had been untrue, it was my fault... I went over and over again in my mind all the circumstantial evidence that it was really our shells I had seen bursting and had horrid doubts and fears."

Lieutenant Mallory went on leave in December 1916. When he returned to the Western Front he became a liaison officer to a French unit. He wrote a letter to his wife about the conditions on the front-line: "The surroundings are indescribably desolate and dotted with small crosses. We haven't many dead in the trenches (at least only one decapitated unfortunate has been discovered below the surface) but those outside could well do with some loose earth over them."

In May 1917 he was forced to return to England to have an operation on an ankle injury that made it very difficult to walk. In September 1917 Mallory was sent to Winchester to train on some new guns. He was later sent on a battery commander's course in Lydd.

Mallory returned to the Western Front in September 1918. He joined 515 Siege Battery RGA near Arras. His commanding officer was Gwilym Lloyd George, the son of David Lloyd George, the prime minister. He was with the company when the Armistice was declared on 11th November 1918.

Mallory served in France until January 1919. He returned to teaching history at Charterhouse and revived the college mountaineering group. Of the original sixty members, twenty-three had been killed and eleven more wounded.

According to the authors of The Wildest Dream: The Biography of George Mallory (2000): "David Pye suspected that George was also affected by guilt, as he had been reconsidering his own approach to teaching, and wondering whether he could have done more for the majority of his pupils rather than the favored few." Mallory, Pye and Geoffrey Winthrop Young, talked about opening their own progressive school.

George and Ruth Mallory both became active in the Labour Party. When the idea of a new progressive school did not get off the ground, Mallory applied unsuccessfully for a job with the Union of the League of Nations, a pressue group that favoured world government.

In 1921 Mallory was invited to join a reconnaissance expedition to Mount Everest. The following year he took part in an attempt to reach the summit, but the group was forced back by bad weather. However, Mallory and his colleagues reached a new world record altitude of just under 27,000 feet, a feat achieved without oxygen. Mallory was asked why he wished to climb Mount Everest and he replied: "Because it is there."

George Mallory was considered to be the best mountain climber in the world. Harry Tyndale, who climbed with Mallory, argued: "In watching George at work one was conscious not so much of physical strength as of suppleness and balance; so rhythmical and harmonious was his progress in any steep place ... that his movements appeared almost serpentine in their smoothness." Geoffrey Winthrop Young added: "His movement in climbing was entirely his own. It contradicted all theory. He would set his foot high against any angle of smooth surface, fold his shoulder to his knee, and flow upward and upright again on an impetuous curve."

Mallory joined another expedition to Mount Everest in 1924. Approaching his 38th birthday, he considered that this would be his last chance to climb the world's highest mountain. Mallory and an excellent young climber, Andrew Irvine, set off from the highest camp for the top on 8th June. Both climbers were seen by Noel Odell through a telescope on the mountain's northeast ridge, only a few hundred metres from the summit. They never returned to high camp and died somewhere high on the mountain.

Robert Graves argued that "anyone who had climbed with George is convinced that he got to the summit." His close friend, Geoffrey Winthrop Young was also convinced that he conquered Everest. He wrote: "After nearly twenty years' knowledge of Mallory as a mountaineer, I can say that difficult as it would have been for any mountaineer to turn back, with the only difficulty past, to Mallory it would have been an impossibility." Tom Longstaff, who took part in the 1922 Everest expedition, added: "It is obvious to any climber that they got up.... Now, they will never grow old and I am very sure they would not change places with any of us."

Over the next thirty years there were several attempts to climb Mount Everest. In 1933, Percy Wyn-Harris discovered Irvine's ice-axe on a rock at around 27,500 feet (8380 m).

Everest was eventually conquered by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on 29 May 1953. They spent only about 15 minutes at the summit. They looked for evidence of the 1924 Mallory expedition, but found none.

In 1975, Wang Hongbao, a Chinese climber reported that he had seen the body of a at 8100m, while attempting to climb Everest. Wang was killed in an avalanche a day after the report and so the location was never precisely fixed. However, the only possible identity of the body was that of Mallory or Irvine.

The Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, led by Eric Simonson, took place in 1999. The frozen body of Mallory was found at 26,760 feet (8,160 m) on the north face of the mountain. The body was remarkably well preserved due to the mountain's climate and from the rope-jerk injury around his waist, encircled by the remnants of a climbing rope, it appears that the two were roped together when Mallory fell. The body lay roughly below the location of Irvine's ice axe found in 1933. The fact that the body was relatively unbroken suggests that Mallory may not have fallen such a long distance as Irvine.

Clare Mallory believes that the evidence suggests that her father did reach the summit. He had promised his wife Ruth Mallory, to leave a photograph of her at the top of the mountain. As no photograph of Ruth was found on Mallory, she is sure that he must have left it on the summit.

Another clue was that Mallory's snow goggles were found in his pocket, suggesting that he and Irvine had made a push for the summit and were descending after sunset.

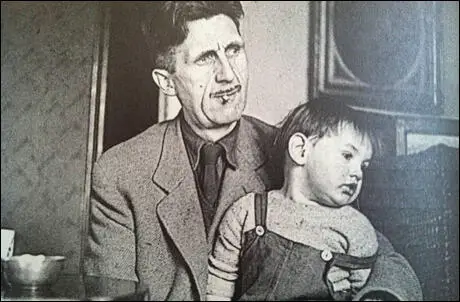

On this day in 1949 George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four is published. In 1945 George Orwell reviewed the anti-Utopian novel We by Yevgeni Zamyatin for Tribune. The book inspired this novel. Published in 1949, the book was a pessimistic satire about the threat of political tyranny in the future. The novel had a tremendous impact and many of the new words and phrases used in the book passed into everyday language.

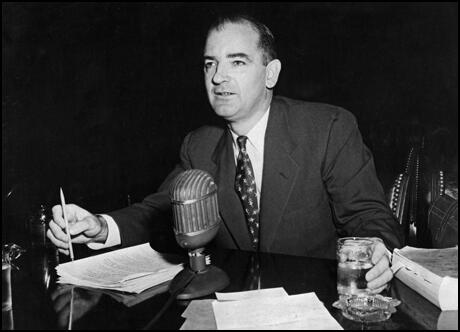

On this day in 1953, Philip D. Reed, head of General Electric, warns President Eisenhower of the dangers of McCarthyism. "I urge you to take issue with McCarthy and make it stick. People in high and low places see in him a potential Hitler, seeking the presidency of the United States. That he could get away with what he already has in America has made some of them wonder whether our concept of democratic governments and the rights of individuals is really different from those of the Communists and Fascists."

On this day in 1969 Richard Nixon announced the first of the US troop withdrawals from South Vietnam. The 540,000 US troops were to be reduced by 25,000. Another 60,000 were to leave the following December. Nixon's advisers told him that they feared that the gradual removal of all US troops would eventually result in a National Liberation Front victory. It was therefore agreed that the only way that America could avoid a humiliating defeat was to negotiate a peace agreement in the talks that were taking place in Paris. In an effort to put pressure on North Vietnam in these talks, Nixon developed what has become known as the Madman Theory. Bob Haldeman, one of the US chief negotiators, was told to give the impression that President Nixon was mentally unstable and that his hatred of communism was so fanatical that if the war continued for much longer he was liable to resort to nuclear weapons against North Vietnam.

Another Nixon innovation was the secret Phoenix Program. Vietnamese were trained by the CIA to infiltrate peasant communities and discover the names of NLF sympathisers. When they had been identified, Death Squads were sent in to execute them. Between 1968 and 1971, an estimated 40,974 members of of the NLF were killed in this way. It was hoped that the Phoenix Program would result in the destruction of the NLF organisation, but, as on previous occasions, the NLF was able to replace its losses by recruiting from the local population and by arranging for volunteers to be sent from North Vietnam.