On this day on 2nd February

On this day in 1650 Nell Gwyn, mistress of King Charles II was born in Hereford. Her family were poor and she sold oranges at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London. She eventually became one of the country's leading comic actresses. Nell Gwyn became the mistress of Lord Buckhurst. In 1669 she became involved with Charles II and gave birth to two children, Charles Beauclerk (later the Duke of St. Albans) and James Beauclerk. Nell Gwyn died of an apoplectic fit in 1687.

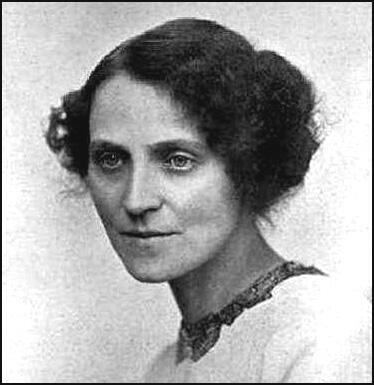

On this day in 1745 Hannah More, the fourth of the five daughters of Jacob More (1700–1783) and Mary Grace, was born at Fishponds, a couple of miles north of Bristol. Her father was a schoolmaster at the local school.

Her biographer, S. J. Skedd, has pointed out: "Hannah More grew up in a loving, intellectual, and predominately female environment. A precocious child and the acknowledged genius of the family, she displayed a quick-witted cleverness and passion for learning which were nurtured not only by her scholarly father, who taught her Latin and mathematics, but also by her mother and sisters."

Jacob More started his own boarding-school at 6 Trinity Street in Bristol. Hannah and her sisters attended the school. She also attended classes at the Bristol Baptist Academy. Later she taught at her father's school. In her late teens Hannah More composed her first significant work, a pastoral verse drama for schoolgirls entitled The Search after Happiness (1762) where she expressed her views on women's education.

In 1767 Hannah More accepted a proposal of marriage from William Turner, of Belmont House, Wraxall. Turner, who was twenty years her senior, postponed their wedding three times; on the first occasion he allegedly jilted her at the altar. More finally broke off their engagement in 1773. It has been claimed that this decision "triggered a nervous breakdown". Soon afterwards she resolved never to marry, and refused several subsequent proposals, including one from the poet John Langhorne. Turner offered her an annuity to enable her to pursue a literary career. She initially declined but finally accepted a smaller annuity of £200. This money gave her financial security and independence.

More was a regular visitor to London where she met David Garrick, Joshua Reynolds, Samuel Johnson, and Edmund Burke. In September 1774 she helped Burke in his successful campaign to be elected MP for Bristol. Garrick put on her first play, The Inflexible Captive, at the Theatre Royal in Bath in April 1775. This was followed by her second play, Percy, that was performed at Covent Garden in December 1777. It was a great success and she made nearly £600 from the rights to the play. Her third and final play, The Fatal Falsehood, was far less popular and played for only a few nights.

In 1777 More published Essays on Various Subjects, Principally Designed for Young Ladies. The eight essays dealt with topics such as education and religion. She suggested that schools should stress "the intellectual, sentimental, and religious education of girls" and argued that women were "one of the principal hinges on which the great machine of human society turns".

More met Charles Middleton and his wife at his home at Barham Court, Teston. She was later introduced to John Newton, William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp and became in their campaign against the slave-trade. More wrote: "I tell him (Middleton) I hope Teston will be the Runnymede of the Negroes, and that the great charter of African liberty will be there completed." In January 1788, she wrote the poem, Slavery, to help publicize Wilberforce's proposed measures against the trade.

In August 1789 Wilberforce stayed with her at her cottage in Blagdon, and on visiting the nearby village of Cheddar and according to William Roberts, the author of Memoirs of the Life and Correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More (1834): they were appalled to find "incredible multitudes of poor, plunged in an excess of vice, poverty, and ignorance beyond what one would suppose possible in a civilized and Christian country". As a result of this experience, More rented a house at Cheddar and engaged teachers to instruct the children in reading the Bible and the catechism. The school soon had 300 pupils and over the next ten years the More sisters opened another twelve schools in the area where the main objective was "to train up the lower classes to habits of industry and virtue".

Michael Jordan, the author of The Great Abolition Sham (2005) has pointed out: "More set up local schools in order to equip impoverished pupils with an elementary grasp of reading. This, however, was where her concern for their education effectively ended, because she did not offer her charges the additional skill of writing. To be able to read was to open a door to good ideas and sound morality (most of which was provided by Hannah More through a series of religious pamphlets); writing, on the other hand, was to be discouraged, since it would open the way to rising above one's natural station."

S. J. Skedd has argued: "More was adamant that the poor should not be taught writing, as it would encourage them to be dissatisfied with their lowly situation; over twenty years later she strongly criticized the National Society for teaching their school pupils the three Rs." Skedd goes onto argue that "the sisters also started evening classes for adults, weekday classes for girls to learn how to sew, knit, and spin, and a number of women's friendly societies, where the virtues of cleanliness, decency, and Christian behaviour were inculcated." Later these schools were handed over to Selina Mills, the future wife of Zachary Macaulay.

Richard S. Reddie has suggested that More was greatly influenced by the ideas of William Wilberforce: "More formed a friendship with William Wilberforce and became the living embodiment of his task to reform manners. If Wesley and the Methodists appeared to concentrate their work on the poor, Hannah More focused on the wealthy farmers and landowners, many of whom were known for their penchant for carousing. With the help of local clergy, she encouraged them to to curb their excessive drinking and coarse behaviour in favour of a more sedate, spiritual existence."

The historian, Linda Colley, described Hannah More in her book, Britons: Forging the Nation 1707-1837 (1992) as "push, humourless and complacent and could be unctuously sycophantic where influential men were concerned, whether they were politicians, peers, ecclesiastics or cultural lions such as Samuel Johnson and David Garrick".

More's campaign against the slave-trade associated her with the French Revolution. She complained to Charles Moss, the Bishop of Bath and Wells: "It has been broadly intimated that I have laboured to spread French principles; and one of my schools is specifically charged with having prayed for the success of the French... I am accused of being the abettor, not only of fanaticism and sedition, but of thieving and prostitution." These charges were untrue as she was a strong opponent of democracy.

Hannah More was concerned about the influence of Tom Paine, whose book, Rights of Man, was circulating in cheap editions, throughout Britain. In 1792 she published Village Politics: Addressed to all the Mechanics, Journeymen, and Day Labourers, in Great Britain (1792). The book attempted to ridicule Paine's political ideas. This was followed by a series of pamphlets on political issues for the lower classes. These were published anonymously as Cheap Repository Tracts (1795–8). The successful banker, Henry Thornton, helped pay for these publications. It has been claimed that within a year these pamphlets sold over 2 million copies. They were mainly bought by the wealthy to distribute to the poor. The success of these publications paved the way for the establishment of the Religious Tract Society.

Hannah More's book, Strictures on the Modern System of Female Education (1799), was a great success with seven editions being printed in the first year alone. In her book she criticised the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Mary Wollstonecraft. She argued that her belief in female rights, encouraged women to adopt an aggressive independence.

More joined the Clapham Set, a group of evangelical members of the Anglican Church, centered around Henry Venn, rector of Clapham Church in London. This inspired the writing of Practical Piety (1811), Christian Morals (1813) and Character and Practical Writings of St Paul (1815). More also became concerned about the growing influence of William Cobbett and his newspaper, The Political Register. Her attack on Cobbett appeared in The Loyal Subject's Political Creed (1817). Cobbett responded by describing More as an "old bishop in petticoats". In 1820 she wrote: "These turbulent times make one sad. I am sick of that liberty which I used so to prize".

Hannah More died, aged eighty-eight, on 7th September 1833. She left over £30,000, most of which she bequeathed to charities and religious societies. Linda Colley has argued that "More had become the first British woman ever to make a fortune with her pen."

On this day in 1838 Thomas Creevey died. Creevey the son of William Creevey, a merchant sea captain, was born in Liverpool on 5th March, 1768. William Creevey transported slaves from Africa and he made enough money to send Thomas to a boarding school in London. He was a good student and at seventeen went to Queens' College, Cambridge.

One of Thomas Creevey's uncles, James Currie, was active in Whig politics and introduced him to Samuel Romilly and James Scarlett. Romilly liked Creevey and helped him become a lawyer. Romilly was impressed by Creevey's progress and arranged for him to meet Lord Petre, the patron of the Thetford constituency. In 1802, Petre asked Creevey to become his candidate at Thetford and at the age of thirty-four entered the House of Commons.

Creevey became a strong supporter of Charles Fox and the radical Whigs in Parliament. In 1806 the prime minister, Lord Grenville, gave Creevey the position of Secretary to the Board of Control in his government. Creevey lost the job when Grenville resigned in 1807.

In the House of Commons Creevey led the fight against the railways. He accepted defeat in was one of those politicians who was invited to the opening ceremony of the Liverpool to Manchester Railway. He wrote in his journal: "Lady Wilton sent over yesterday from Knowsley to say that the locomotive machine was to be upon the railway at 12 o'clock. I had the satisfaction, for I can't call it pleasure, of taking a trip of five miles on it, which we did in just a quarter of an hour - that is twenty miles an hour. The machine was really flying, and it is impossible to divest yourself of the notion of instant death to all upon the least accident happening. It gave me a headache which has not left me yet."

Thomas Creevey lost his seat at Thetford but in 1820 he became the MP for Appleby. Later he moved to the rotten borough of Downton. When Lord Grey became prime minister in 1830, he gave Creevey the post of Treasurer of the Ordnance. Creevey loyally supported Grey's proposals for parliamentary reform and argued for the 1832 Reform Act.

On the 26th May 1832 he wrote to a friend about the Duke of Wellington opposition to change: "One more day will finish the concern in the Lords, and that this should have been accomplished as it has against a great majority of peers, and without making a single new one, must always remain one of the greatest miracles in English history. He (the Duke of Wellington) has destroyed himself and his Tory high-flying association for ever. This (the Reform Act) has saved the country from confusion, and perhaps the monarch and monarchy from destruction."

As a result of the 1832 Reform Act, Downton lost its right to send a MP to the House of Commons. Thomas Creevey died in Greenwich on 2nd February, 1838.

On this day in 1839 the Female Political Union of Newcastle published their demands in the Northern Star: "We have been told that the province of women is her home, and that the field of politics should be left to men; this we deny. It is not true that the interests of our fathers, husbands, and brothers, ought to be ours? If they are oppressed and impoverished, do we not share those evils with them? If so, ought we not to resent the infliction of those wrongs upon them? We have read the records of the past, and our hearts have responded to the historian's praise of those women, who struggled against tyranny and urged their countrymen to be free or die. For years we have struggled to maintain our homes in comfort, such as our hearts told us should greet our husbands after their fatiguing labours. Year after year has passed away, and even now our wishes have no prospect of being realised, our husbands are over-wrought, our houses half furnished, our families ill-fed, and our children uneducated. We are a despised caste; our oppressors are not content with despising our feelings, but demand the control of our thoughts and wants! We are oppressed because we are poor - the joys of life, the gladness of plenty, and the sympathies of nature, are not for us; the solace of our homes, the endearments of our children, and the sympathies of our kindred are denied us - and even in the grave our ashes are laid with disrespect."

On this day in 1854 pioneer sociologist, Mary Kingsland, the daughter of William Kingsland (1826–1876), a Congregational minister, was born in Devizes, Wiltshire. When Mary was a child, her father became minister of the College Chapel in Bradford.

After being educated at home she went to a local private school at the age of thirteen. In 1871 she won an exhibition to the Hitchin College for Women. Two years later she transferred to Girton College, an educational institution founded by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon in 1870. Mary was the first woman at the university to study for the Natural Science Tripos and in 1874 she gained a second-class honours degree.

For the next eighteen months she worked as a assistant lecturer at Girton. She then returned to Bradford where she taught mathematics and science at the recently established grammar school for girls in the city. She later taught at the Saltaire School in Shipley.

On 5th August 1879, she married Thomas Kilpin Higgs (1851–1907). She now moved to Hanley where her husband was a Congregational minister. Over the next few years she gave birth to four children. The family moved to Oldham where Higgs served as minister of Greenacres Congregational Church.

Mary Higgs became involved in a wide range of religious and philanthropic organisations. This included Secretary of the Oldham Workhouse Ladies Visiting Committee and the organiser of a home for destitute women. She also became friends of William Stead, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette and Ebenezer Howard, the founder of the garden city movement. Inspired by the ideas of Howard, she established the Beautiful Oldham Society in 1902.

Higgs became concerned about the scale of poverty she saw and carried out a study of the lives of homeless people in Oldham. Encouraged by the work of James Greenwood, who was the first journalist to use the pioneering technique of temporarily adopting the dress and circumstances of others, she decided to carry out a detailed study of poverty in the town.

According to her biographer, Rosemary Chadwick: "Mary Higgs... over many years from 1903 took the highly unusual step (for a middle-class woman) of visiting workhouse wards and common lodging-houses dressed as a tramp. Her vivid accounts of the dirt and degradation which she encountered and of the downward spiral of destitution in which homeless women found themselves helped to fuel demands for more and better regulated women's lodgings, and for lodgings geared to the needs of migrant workers." Three Nights in Women's Lodging Houses was published in 1906. This was followed by Glimpses Into the Abyss (1907).

Chadwick goes on to argue: "Higgs was an early advocate of family allowances, widowed mothers' pensions, and insurances for other life events. Her Oldham home, Bent House, served as a base for countless welfare organizations, many brought together in the Council of Social Welfare. Mobilizing an army of helpers, she established a paper-sorting industry to employ destitute women, pioneered mother and infant welfare centres, and founded Oldham's first evening play centre."

Mary Higgs devoted the rest of her life to social work in Oldham and was awarded an OBE just before her death on 19th March 1937.

On this day in 1914 Dora Marsden criticised Christabel Pankhurst for upholding the values of chastity, marriage and monogamy. In 1913 Pankhurst published The Great Scourge and How to End It. She argued that most men had venereal disease and that the prime reason for opposition to women's suffrage came from men concerned that enfranchised women would stop their promiscuity. Until they had the vote, she suggested that women should be wary of any sexual contact with men. Marsden criticised Pankhurst for upholding the values of chastity, marriage and monogamy. She also pointed out in The Egoist on 2nd February 1914 that Pankhurst's statistics on venereal disease were so exaggerated that they made nonsense of her argument. Marsden concluded the article with the claim: "If Miss Pankhurst desires to exploit human boredom and the ravages of dirt she will require to call in the aid of a more subtle intelligence than she herself appears to possess." Other contributors to the journal joined in the attack on Pankhurst. The Canadian feminist, R. B. Kerr argued that "her obvious ignorance of life is a great handicap to Miss Pankhurst" (16th March, 1914) whereas Ezra Pound suggested that she "has as much intellect as a guinea pig" (1st July, 1914).

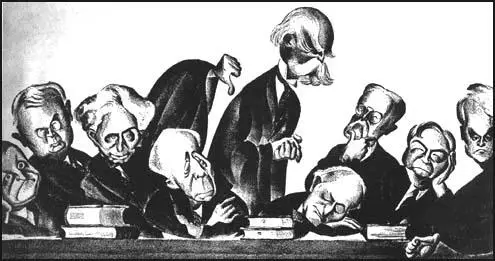

On this day in 1937 President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a speech attacking the Supreme Court for its actions over New Deal legislation.

The Supreme Court is the highest federal court in the United States. Its existence is provided for in Article III of the Constitution, although Congress is given the power to determine the size of the Court. The size of the court is set by Congress and currently consists of a Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices.

Members of the Supreme Court are appointed for life by the President. They may be removed only by death, resignation or impeachment. The Supreme Court has the power of judicial review. It may declare acts of Congress or of state governments unconstitutional and therefore invalid. The Supreme Court decides cases by a majority vote and its decisions are final.

President Roosevelt came into conflict with the Supreme Court during his period in office. The chief justice, Charles Hughes, had been the Republican Party presidential candidate in 1916. Herbert Hoover appointed Hughes in 1930 and had led the court's opposition to some of the proposed New Deal legislation. This included the ruling against the National Recovery Administration (NRA), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) and ten other New Deal laws.

On 2nd February, 1937, Franklin D. Roosevelt made a speech attacking the Supreme Court for its actions over New Deal legislation. He pointed out that seven of the nine judges (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, George Sutherland, Harlan Stone, Owen Roberts, Benjamin Cardozo and Pierce Butler) had been appointed by Republican presidents. Roosevelt had just won re-election by 10,000,000 votes and resented the fact that the justices could veto legislation that clearly had the support of the vast majority of the public.

Roosevelt suggested that the age was a major problem as six of the judges were over 70 (Charles Hughes, Willis Van Devanter, James McReynolds, Louis Brandeis, George Sutherland and Pierce Butler). Roosevelt announced that he was going to ask Congress to pass a bill enabling the president to expand the Supreme Court by adding one new judge, up to a maximum off six, for every current judge over the age of 70.

Charles Hughes realised that Roosevelt's Court Reorganization Bill would result in the Supreme Court coming under the control of the Democratic Party. His first move was to arrange for a letter written by him to be published by Burton Wheeler, chairman of the Judiciary Committee. In the letter Hughes cogently refuted all the claims made by Roosevelt.

However, behind the scenes Hughes was busy doing deals to make sure that Roosevelt's bill would be defeated in Congress. On 29th March, Owen Roberts announced that he had changed his mind about voting against minimum wage legislation. Hughes also reversed his opinion on the Social Security Act and the National Labour Relations Act (NLRA) and by a 5-4 vote they were now declared to be constitutional.

Then Willis Van Devanter, probably the most conservative of the justices, announced his intention to resign. He was replaced by Hugo Black, a member of the Democratic Party and a strong supporter of the New Deal. In July, 1937, Congress defeated the Court Reorganization Bill by 70-20. However, Roosevelt had the satisfaction of knowing he had a Supreme Court that was now less likely to block his legislation.

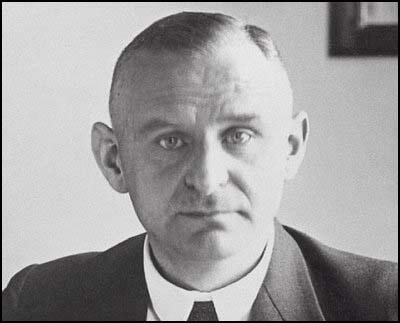

On this day in 1945 Carl Goerdeler was executed. Goerdeler, the son of a Prussian district judge, was born in Schneidemuell on 31st July 1884. After studying law he became a local civil servant. In 1930 Goerdeler became mayor of Leipzig. He also became price commissioner in the government of Heinrich Brüning and remained in office when Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. Goerdeler resigned in 1934 after disagreement with Hitler over his policies.

Goerdeler publically opposed German rearmament and the Nuremberg Laws. As mayor of Leipzig he refused to pull down the statue of the Jewish composer Felix Mendelssohn or to fly the swastika flag over the city hall.

Goerdeler resigned as mayor of Leipzig in 1937 and spent the next two years travelling around Europe as overseas representative of the Bosche company. In 1938 he met Winston Churchill and other important political figures in Britain and France. Goerdeler provided information about Nazi Germany and encouraged governments not to make too many concessions to Hitler. He was appalled by the Munich Agreement which he saw as "out-and-out capitulation" and claimed that it would lead to a war in Europe.

During the Second World War Goerdeler advocated a negotiated peace with the Allies. However, he was deeply disappointed when his political contacts in Britain told him that the war would only come to an end if Germany unconditionally surrendered.

By 1940 Carl Goerdeler had become convinced that only the German armed forces could overthrow Hitler. He made contact with Ludwig Beck but they were unable to find enough senior military leaders to take part in a coup.

In 1944 Goerdeler became involved in the July Plot and he agreed to become chancellor after Hitler's assassination. On 18th July, 1944, Goerdeler was warned that the Gestapo had discovered that he was involved in a conspiracy to kill Hitler. He went into hiding but was arrested the following month on 12th August. Carl Goerdeler was interrogated and tortured for five months before being executed on 2nd February.

On this day in 1945 Marie Brackenbury died. The last survivor of the immediate family, she left the house to the Over Thirties Association. The Suffragette Fellowship commissioned a plaque to be attached to the house. It read "The Brackenbury trio were so whole-hearted and helpful during all the early strenuously years of the militant suffrage movement. We remember them with honour."

Marie Brackenbury, the daughter of Hilda Brackenbury, and the sister of Georgina Brackenbury, was born on 15th October 1866. Her father, Charles Brackenbury, was an army general and two of her brothers died while serving in the armed forces.

Brackenbury studied at the Slade Art School and became a talented landscape painter. A member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in March 1907. Marie later recalled that she had been impressed with the "womanliness" of Emmeline Pankhurst.

In February 1908, Marie Brackenbury and her sister Georgina Brackenbury were arrested in February 1908 during a WSPU demonstration outside the House of Commons and was sentenced to six weeks in Holloway Prison. Later that year she contributed a cartoon to the Woman's Franchise journal.

Marie visited Eagle House near Batheaston on 22nd July 1910 with her sister Georgina Brackenbury. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Cupressus Lawsoniana Filifera, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

Christabel Pankhurst decided that the WSPU needed to intensify its window-breaking campaign. On 1st March, 1912, a group of suffragettes volunteered to take action in the West End of London. The Daily Graphic reported the following day: "The West End of London last night was the scene of an unexampled outrage on the part of militant suffragists.... Bands of women paraded Regent Street, Piccadilly, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street, smashing windows with stones and hammers."

Marie Brackenbury and her mother, were both arrested for taking part in the demonstration. Hilda Brackenbury, aged 79, was accused of breaking two windows in the United Service Institution in Whitehall. She served eight days on remand before being sentenced to 14 days in Holloway Prison. In court Marie claimed that she was "a soldier in this great cause". She was sentenced to two weeks in prison.

Mrs Brackenbury's home at 2 Campden Hill Square, London, became known as "Mouse Castle" as members of the WSPU went there to recuperate after being released under the Cat & Mouse Act.

On this day in 1954 Edith How-Martyn died.

Edith How was born on 17th June, 1875. She was educated at the North London Collegiate School for Girls, a school formed and run by Frances Buss, an early supporter of women's suffrage. After obtaining a degree from University College, Aberystwyth, she became a lecturer at mathematics at Westfield College, but this came to an end when she married Herbert Martyn.

Edith How-Martyn was an early recruit to the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and was arrested in 1906 for trying to make a speech in the lobby of the House of Commons and was one of the first members of the organisation to be sent to prison.

Edith How-Martyn was critical of the dictatorial way that Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst led the WSPU. At a meeting in October 1907, Edith How-Martyn, Teresa Billington Greig, Charlotte Despard and seventy other women attempted to make the WSPU a more democratic organisation.

When their efforts failed, the three women left the WSPU and formed the Women's Freedom League. This new organisation still took a militant approach but unlike the WSPU the Freedom League concentrated on using non-violent illegal methods. As the leading figure of the Women's Freedom League, Edith How-Martyn urged members not to pay taxes and to boycott the 1911 Census.

After the passing of the passing of the Qualification of Women Act, How-Martin stood as an Independent Feminist candidate in the 1918 General Election. This approach failed to appeal to the electorate and she lost her deposit. How-Martyn had more success when she stood for the Middlesex County Council and became its first woman member.

How-Martyn was active in the campaign for birth-control led by Marie Sopes after the war. How-Martyn was particularly concerned about working class women who had little information how to control the size of their families. In 1929 she founded the Birth Control Information Centre to spread such knowledge.

Edith How-Martyn emigrated to Australia in 1939.