Autobiography of John Simkin

John Berger: “Autobiography begins with a sense of being alone. It is an orphan form.”

Robert A. Heinlein: “Autobiography is usually honest but it is never truthful.”

Mark Twain: “There was never yet an uninteresting life. Such a thing is an impossibility. Inside of the dullest exterior there is a drama, a comedy, and a tragedy.”

"Where is my mummy" are the first words I remember saying. I even know the date I said them - 12th May 1949. I was three years and 11 months old and I was lying in bed next to Tricia, my 7-year-old sister. The woman leaning over us was my grandmother, Elizabeth Hughes, who was trying to put drops in our eyes. Apparently, we were both suffering from conjunctivitis. Her reply was that my mother was in hospital having a baby. That is of course why I can be so sure of the date. It was the birth of my brother David.

I don't remember being told my mother (Muriel Simkin) was expecting a baby. A few years later, my aunt (Stella Hughes, my mother's sister) also had a baby. I remember not being told about this until the baby was born. Maybe my memory is playing tricks, but it seems that it was something they did not tell children about such things. It was as if they were ashamed about getting pregnant. As if they felt guilty about bringing another child into the world. In those days, for the working-class, it was always a massive financial commitment to have another child.

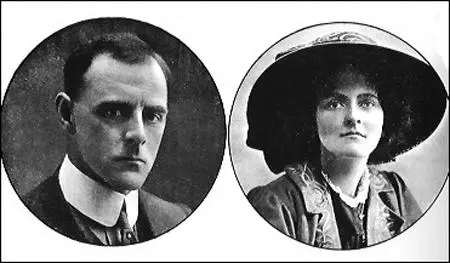

Elizabeth and Thomas Hughes

I was not really pleased that my grandmother was looking after me. I know that in most cases, spending a couple of nights with your grandparents is exciting. That was not the case in our family. Grandmother Hughes lived close by and I saw a great deal of her. I do not remember her saying anything nice to me. The only time she spoke to me she appeared to be telling me off. So different from my mother. I am not sure she ever smiled, unless she was being photographed. She appeared dissatisfied with life. Her husband (Thomas Griffiths Hughes), who died when I was eight, played no role in my life. Tricia had fond memories of him as he gave her money for going to the shops to buy his tobacco. My mother told me that he was a lovely man, but had a major flaw, he was a heavy drinker. Although highly intelligent his dependence on alcohol always held him back in developing a successful career. I would image it was his heavy drinking that made my grandmother so miserable.

My grandmother did not treat my mother very well. She nagged her in the same way she treated me. I suspect she resented having my mother. My brother David has done considerable research into our family history. He discovered that my grandmother was pregnant before she got married. I am not sure my mother realised this, but my grandmother did once tell her that she was about to go to America as Sybil Thorndike's personal maid at their home in Westminster, when she discovered she was pregnant.

In 1914, the year that my mother was born, Sybil Thorndike, was one of Britain's leading actresses. She had been discovered by George Bernard Shaw when she was a teenager. In 1908, she took the leading role of Candida in a tour directed by Shaw himself. She married the English actor and theatre director, Lewis Casson on 22nd December, 1908. Elsie Fogerty, the founder of the Central School of Speech and Drama, told Sybil: "You're a lucky girl to have married Lewis Casson. It's the best voice on the stage, the purest production - and I hope you are worthy of it." They quickly had three children: John (1909), Christopher (1912) and Mary (1914). My grandmother obviously helped to look after these children as Thorndike continued with her career during this period. It also raises the issue if Thomas Hughes was my mother's father. Casson was a famous womaniser and is it possible that he was really the father? The photograpabove shows he has the family look of disapproval. But clearly, we have not inherited his speaking voice.

John and Jane Simkin

My father's mother, Jane Simkin, also lived close to our house but played no role in my upbringing. She claimed that she came from gypsy stock and that she could predict the future. My older sister, Tricia, used to tell the story that when we were very young, she predicted the future for us children. Tricia was going to suffer from health problems (she did) and my brother David was going to be very intelligent (he is). I was to be the lucky one. Except for two major tragedies in my life, she was right. However, as the golfer Gary Player once said, "the harder I practice, the luckier I get." Or in the words of Confucius: “The more you know, the more luck you will have.”

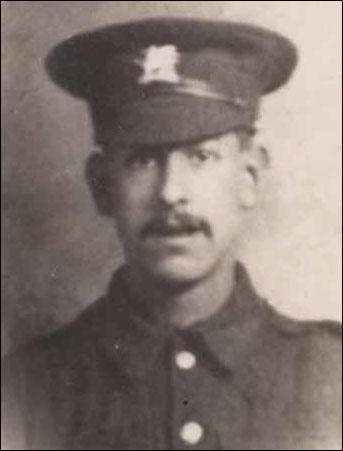

My father's father, John Edward Simkin, was killed during the First World War. It is a mystery why he volunteered for the British Army in 1915. Over 750,000 men had enlisted by the end of September 1914. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until the beginning of 1915 when numbers joining began to slow down as news arrived back home about the truth of trench warfare on the Western Front.

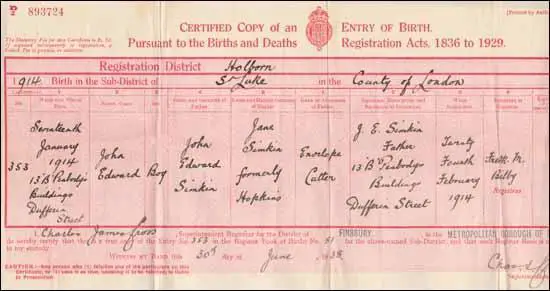

My grandfather had a reasonable job, an "envelope cutter" at the De La Rue & Company. In 1910, John Simkin married Jane Hopkins in Shoreditch. The couple's first child Elsie was born in 1912. My father arrived on 17th January 1914 in Finsbury. A third child William Valentine Simkin was born on 14th February 1915. He was 32 years-old with three young children and was under no pressure to join the army (younger men were given white feathers by young women if not in uniform).

Despite this he joined the Royal East Kent Regiment. He arrived at Boulogne with the 7th Battalion in July 1915. When he reached the Western Front at the Somme, he was attached to the 178th tunnelling company. Where possible, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels under No Man's Land. The main objective was to place mines beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine.

Soldiers in the trenches developed different strategies to discover enemy tunnelling. One method was to drive a stick into the ground and hold the other end between the teeth and feel any underground vibrations. Another one involved sinking a water-filled oil drum into the floor of the trench. The soldiers then took it in turns to lower an ear into the water to listen for any noise being made by tunnellers. When an enemy's tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

It appears that my grandfather was involved in tunnelling under the German frontline on 29th August 1915, when a mine exploded. He was killed with two other men. Five others in the 178th tunnelling company were badly injured. John Edward Simkin was buried alive and his body has never been recovered. His name appears on the Thiepval War Memorial. He left no letters and it has been impossible to discover anything about his thoughts on any subject. The family only has the photograph above and the "He Died for Freedom and Honour" medal that was given to the families of dead soldiers.

These medals or plaques were 4.75 inches (120 mm) in diameter and were cast in bronze. Later it came to be known as the "Dead Man's Penny". As a young child I was fascinated by this medal. You could argue that it was the first time I became interested in history. As a child I was proud of my grandfather for giving his life to defend the British Empire. However, as I got older, and I read and wrote a great deal about the conflict, I changed my mind and considered him someone who should have been more politically aware of what was really going on.

I have often thought that he would have been the grand parents that I would have connected with and would have become an important influence on my personality. However, I expect that like my other grandparents he would have turned out to be a disappointment.

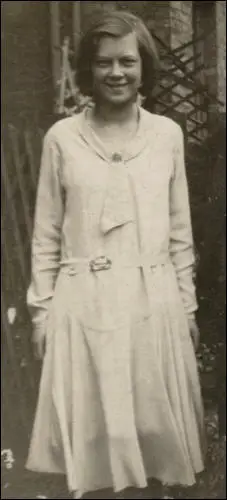

Muriel Hughes

In 1987 I spent several days interviewing my mother (Muriel Simkin) on tape about her life. She was seventy-three at the time and her recall of the past was very impressive. Mum really enjoyed the experience and told me stories that a woman would normally only tell her psychiatrist. When she was in her eighties, I interviewed her again, this time with a video camera. This was not a good idea. The camera seemed to intimidate her, and she struggled to tell the same stories in as much detail. During this time, my brother David also interviewed her about her life. Therefore, we have a considerable amount of information about her and the Hughes family. David is also responsible for collecting and cataloguing the family photographs.

Muriel Millicent Hughes, the first of three children, was born at No.2 Halidon Street, Hackney, London, on 29th July 1914. Her mother, Elizabeth Kershaw Hughes, was only nineteen, whereas her father, Thomas Griffiths Hughes, was thirty-four. My grandmother, second eldest of thirteen children, was a "lady's maid" in the employment of the famous actress Sybil Thorndike (see above) and my granddad a commercial traveller in the drapery trade.

Mum claimed that her first memory of life was seeing her mother and her best friend and cousin, Elizabeth "Nellie" Stubbs, helping her father get ready for going to war. They were putting on his puttees that covered the lower part of the leg from the ankle to the knee. Puttees consisted of a long narrow piece of cloth wound tightly, and spirally round the leg, that was supposed to provide both support and protection. Mum remembers a great deal of laughter and her dad saying, "why are you in such a hurry, what do you plan to do while I'm away?"

As the war ended in 1918 mum must have been three or four at the time but she insists she remembers this event in great detail. Conscription began on 2nd March 1916, and originally specified that single men between the ages of 18 and 41 were liable to be called-up for military service unless they were widowed with children or ministers of religion. The Military Service Act was extended to married men on 25th May 1916. Given his age and marriage status I suspect the date was late 1917 or early 1918. Mum says he joined the Royal Medical Corp and did not see any action. Mum's sister Stella says the reason for this was he was kept in quarantine because he was a diphtheria carrier (someone whose cultures are positive for the diphtheria species but does not exhibit signs and symptoms).

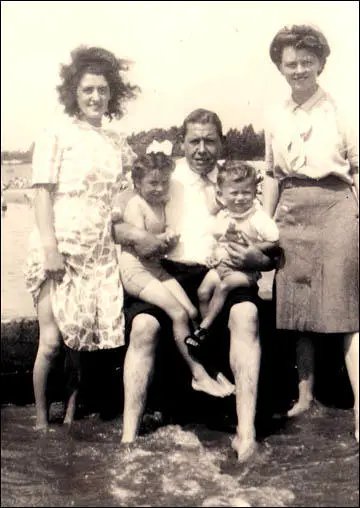

Elizabeth and Thomas Hughes (sitting in the middle of the picture) in a photograph

taken in 1922. Tom Hughes, Muriel's father, holds his son, two-year-old John Hughes.

The girl sitting at the extreme right of the picture is Muriel's cousin Charlotte.

Another relative, Violet, sits between Muriel and her mother.

On his return my grandmother had two more children, John (always known as Jack) in 1920 and Stella in 1926. Stella is still alive and now in her 90s she has provided me with important information on my mum and dad. When she was five or six, my mum began attending the Rams Episcopal Infant School in Hackney and she finished her education in 1928 at the Hackney Free & Parochial School.

My mum and her sister Stella both told me their parents were very strict. Although my grandfather was a commercial traveller and went to work in a suit and tie, they had very little money. Stella said that every morning before work he would place two old pence on the table to pay for food for the family. However, if there was a knock on the door, he would always put on his suit jacket before answering it. Stella said that both her mum (a former maid) and dad were fanatical about table-manners. For example, elbows on the table were strictly forbidden.

Mum passed an examination that would have allowed her to stay on at school, but family finances meant that she had to leave at the age of fourteen. Even in old age mum had lovely handwriting and had a good memory for spelling. I always considered my mum as an intelligent woman. Not in an academic sense (her mother had told her that girls should not read books) but she had good insight into people's characters. In current psychological terms, she had emotional intelligence. Her interest in other people made her popular with friends and family. However, she never made demands on people, including me, and some people exploited this character trait.

Muriel Hughes, then aged about fourteen, is the young girl in the white dress sitting

at the rear of the charabanc with her family. my grandmother, sits propped up to the

right of her daughter. My grandfather is seated right at the back of the charabanc

flanked by Muriel's two siblings, Stella, aged two and her eight year old brother Jack.

Mum's first job at the age of fourteen was at Barlow's Metal Box Factory in Hackney's Urswick Road. On her first day at the factory, my grandmother insisted that mum wear her "Velour" school hat to work. The headgear had been purchased for school wear, but "as the hat had cost money, she had to make use of it". As she left the house wearing the hated school hat, Mum was told by her mother to look after the hat as it was "expensive". On her first day at work, the hat was blown off her head by a gust of wind and went under the wheels of a lorry.

Barlow's Metal Box Factory was close to her home but soon afterwards the family moved to Lea Bridge Road in Leyton and my mum continued to work at the Metal Box Factory. My mum worked from 8 am to 6 pm, making the hour's journey to the factory on foot to save the penny which could have been spent on the tram fare. This included a three mile walk across the Hackney Marshes. This is one of the largest areas of common land in London, with 136.01 hectares (336.1 acres) of protected commons.

I was shocked when she told me this story. I pointed out that in the winter she would have had to walk across the marsh in the dark and this must have been extremely hazardous for a teenage woman to do such a thing. Mum replied that she did not see it as dangerous at the time as you never heard about people being attacked on Hackney Marsh. She added that it was different today as television and newspapers keep you informed about women being raped and murdered.

In 1928, mum earned 5s 6d a week at the Metal Box factory. Mum later recalled how after a week's labour, she kept one shilling for herself and handed over the remaining 4s 6d to my grandmother for "housekeeping". In 1932, mum secured employment with the large tailoring firm of Horne Brothers, a company which made men's suits and trousers at premises in South Hackney.

In 1932, aged 18, she had her first romantic relationship. Tom Heath worked at Horne Brothers and was 26 years-old. They only went out a couple of times and she insisted that their evening out always ended up with a handshake. Another problem was that while living with her parents she had to arrive home by 10.00 pm. The relationship came to an end when a workmate informed her that he was married. When mum told me this story, nearly fifty years later, she still showed guilt about this misjudgment.

My mum's uncle, Joe Hughes, lived in a flat in Garnham Street, Stoke Newington. In 1935 he moved to a flat in Ilford. The family who moved into the flat in Garnham Street, was my grandmother, Jane Simkin, who was now known as Jane White, and her three children, John (21), William (20) and their half-sister, Lily White (15). They were having trouble with their radio aerial and my mum was asked by her uncle to go round to show them how it had to be positioned.

Both of Mrs White's sons showed an interest in twenty-year-old Muriel. Bill wanted to ask her out, but John (known to all of his friends as Ted) told his mother, that he had just met "the girl he was going to marry". Bill was the first one to make a move, but it was Ted who successfully invited her to go out with him to see the film Mutiny on the Bounty, starring Charles Laughton and Clark Gable. As a result of the "10 o'clock rule" the missed the end of the main film (in those days cinemas showed two films at a time).

Stella was only 8 years old when my dad took my mum on their first date. Stella was anxious to see the new boyfriend and when he brought her back home she leant over the upstairs bannister rails. However, she could not see him as he was standing outside, but she could hear him singing a song to my mum, Without a Word of Warning, a hit for Bing Crosby that first appeared in the film, Two for Tonight (1935).

Ted Simkin worked at the large Mac Fisheries depot at Finsbury Park in North London and spent time as a porter at the famous Billingsgate Fish Market before becoming a "fish salesman". Mum talked fondly about the high-quality fish he was able to supply free of charge to the Hughes family. According to my mum, during this period, dad had a very outgoing personality, and with his accordion playing, he was a popular guest at parties.

Stella says that my dad was always telling jokes and was a very funny man (this is not how I remember him). He was also a fanatical Spurs supporter and he often took her to White Hart Lane to see games. Mum was not interested in football and stayed at home. Stella admitted she was not interested either but she took the opportunity to go out with my dad. However, she soon learnt to love the game and has been a life-long supporter of Spurs.

Dad had not known his father, John Edward Simkin, who had been killed on the Western Front in 1915 when he was only one year old. He did not see much of his stepfather, Harry White, who left the family home when he was very young, According to my mum it seems that an older colleague at work, Izzie Wright, became a father figure. In the early days of their relationship they went on outings to the countryside or the seaside with other couples, including Izzie and his wife Lilly, and Muriel's cousin Winnie Treweek and her new husband George Logsdon.

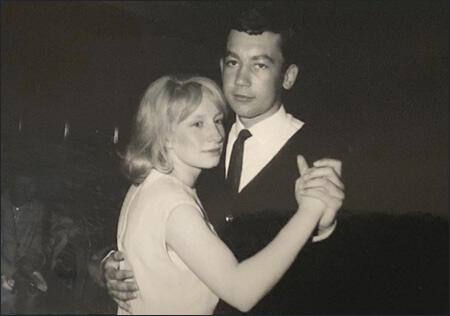

Muriel and John Simkin

Muriel Hughes married Ted Simkin at West Hackney Church, Stoke Newington on 26th August 1939. They went away for two weeks at Weymouth. Unfortunately, the Second World War began a week later and they came home early. Mum recalled: "We were on our honeymoon when war was declared. We had planned to have a fortnight's holiday, but we had to come home after a week. It was not a very good start to our married life."

Ted Simkin, was photographed Louis Edward Muller, a German immigrant.

Stella Hughes, her sister and Winnie, her future sister-in-law.

On their return they moved into their new council house in 98 Rogers Road, Dagenham, Essex. At the time of her marriage, Mum was employed as an "Examiner and Finisher" at the London tailoring firm of Horne Brothers, earning 8s 6d a week. On the first day of war, Parliament passed the National Service (Armed Forces) Act, under which all men between 18 and 41 were made liable for conscription. The registration of all men in each age group in turn began on 21st October for those aged 20 to 23. Dad continued his work as a salesman at the fish market until he was conscripted into the Royal Artillery on 15th July 1940.

My mother later recalled: "I went with my parents to London to see off my husband and brother. They had both been called up by the army. After we left them at the railway station we got caught in an air-raid. We had to get off the bus after it caught fire. We ran for shelter. While we were running, I looked at my dad and he appeared to be on fire. I said: "Dad, you're alight." He nearly had a heart attack and I was not very popular when he discovered that I was mistaken and that it was only the torch in his pocket that had been accidentally turned on while he was running."

Young women without children were encouraged to do war work. Mum left Horne Brothers and joined the Briggs munitions factory in Dagenham. During the Blitz, these factories were a major target for the Luftwaffe. Mum's work was highly dangerous: "It was a terrible job, but we had no option. We all had to do war work.... We had to wait until the second alarm before we were allowed to go to the shelter. The first bell was a warning they were coming. The second was when they were overhead. They did not want any time wasted. The planes might have gone straight past and the factory would have stopped for nothing."

These regulations made the work especially precarious. "Sometimes the Germans would drop their bombs before the second bell went. On one occasion a bomb hit the factory before we were given permission to go to the shelter. The paint department went up. I saw several people flying through the air and I just ran home. I was suffering from shock. I was suspended for six weeks without pay. They would have been saved if they had been allowed to go after the first alarm... We were risking our lives in the same way as the soldiers were."

On the outbreak of the war, Sir John Anderson, the Home Secretary and the Minister of Home Security, commissioned the engineer, William Patterson, to design a small and cheap shelter that could be erected in people's gardens. Within a few months nearly one and a half million of these Anderson Shelters were distributed to people living in areas expected to be bombed by the Luftwaffe. Anderson shelters were given free to poor people. Men who earned more than £5 a week could buy one for £7. The main problem was that under a quarter of the public had no gardens. Made from six curved sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end, and measuring 6ft 6in by 4ft 6in (1.95m by 1.35m) the shelter could accommodate six people. These shelters were half buried in the ground with earth heaped on top. The entrance was protected by a steel shield and an earthen blast wall.

Mum had one of these shelters in her garden. "We had an Anderson shelter in the garden. You were supposed to go into the shelter every night. I used to take my knitting. I used to knit all night. I was too frightened to go to sleep. You got into the habit of not sleeping. I've never slept properly since. It was just a bunk bed. I did not bother to get undressed. It was cold and damp in the shelter. I was all on my own because my husband was in the army."

In 1940 mum and dad had a lucky escape: "You would go nights and nights, and nothing happened. On one occasion when my husband was on leave, I think it was a weekend, we decided we would spend the night in bed instead of in the shelter. I heard the noise and woke up and I would see the sky. They had dropped a basket of incendiary bombs and we had got the lot. Luckily not one went off. Next morning the bombs were standing up in the garden as if they had grown in the night."

Mum claimed that certain things improved during the war: "People on the whole were more friendly during the war than they are today - happier even. People helped you out. You had to have a sense of humour. You couldn't get through it without that. The worst part was having you husband and brothers away from you. We never heard from Jack, my brother, for five months. He couldn't communicate at all because he was involved in important battles in North Africa. It was very worrying. We knew a lot of his regiment had been killed. Then we saw his picture in the Daily Express newspaper. He was being inspected by General Montgomery. It was not until then that we knew he was alive."

in North Africa in 1942. Corporal Jack Hughes, Muriel Simkin's younger brother

stands on the far left of the row of soldiers.

Mum managed to survive the bombing raids, but the extended family did suffer one major tragedy. "Rosie, my mum's sister, had to go to hospital to have a baby. Her mother-in-law looked after her three-year-old son. There was a bombing raid and Rosie's son and mother-in-law rushed to Bethnal Green underground station. Going down the stairs somebody fell. People panicked and Rosie's son was trampled to death."

My dad's Royal Artillery unit was based in southern England during the war. He operated anti-aircraft guns at what became known as "Hell's Corner". At various times he was based at Biggin Hill, Rochford, and Dover. This enabled him to get home occasionally and this resulted in the birth of Patricia (7th March, 1942) and myself (25th June, 1945).

Simkin Family - Post-War

1945 would have been a difficult year for my sister Patricia Simkin (the family called her Tricia). For the first three years of her life she had her mother to herself. With me being born and my dad returning from the war, she now had to share the attentions of her mother with two other people. It left a lasting impression on her personality. She never really forgave her father for being more interested in me than her.

I am afraid my father will have to take responsibility for this. He should have been more aware the impact his behaviour was having on his daughter. In his defence, he came back from the war with serious psychological damage. Like most men in the armed forces he had to suffer the guilt of having to kill people. He was an anti-aircraft gunner and although he did not have the pain of seeing the faces of people he killed, but he would have been in no doubt that his actions would have brought down aircraft with the resulting casualties.

During September 1940, AA batteries defending London fired 260,000 rounds of heavy ammunition. It is estimated that it brought down only one aircraft for every 30,000 shells fired. This dropped to 11,000 in October and by January 1941 the experience gained by the operators, had reduced this figure to 4,000. Another reason was the establishment of a chain of radar warning stations. There was no doubt that he knew that he had killed people, something that he and the other men had been brought up not to do.

Dad also had serious problems with his left-hand. During the Second World War he had an accident on his anti-aircraft gun. This required him to be taken to Canterbury Hospital. One of the doctors noticed that he had warts on his hands. Dad replied that it was a common problem for men who handled fish. Medical studies have shown that these men have a HPV7 infection (Human Papilloma Virus). These warts look unpleasant but are benign. However, this doctor said he had a new treatment that would remove the warts. The new treatment was radiotherapy. X-ray treatment was used as a standard treatment for warts in the 1940s. Patients were given from a single dose to multiple doses of radiation and often the X-ray treatment was combined with other kinds of treatments, such as dressings containing salicylic acid.

In an article published in a medical journal in August 1978, it was claimed that the evidence showed that there were very few cases of adverse effects of radiotherapy, such as radio-dermatitis and ulcerations. Unfortunately, that was not the case with my father and his hand appeared to be dying. I have memories of him sitting in the armchair with him staring at his raised hand that varied in colour from a silver grey to a dark mauve. He received regular treatment at Queen Mary's Hospital in Roehampton. At the time it was mainly used as a military hospital and specialised in the care of amputees became a world-renowned limb fitting and amputee rehabilitation centre.

Over the next few years, he had parts of some fingers removed. This treatment prevented him resuming his work at Billingsgate Market. Instead, he got a job with the Ever-Ready Electrical Company at their factory in Tottenham. He was understandable unhappy about the change of occupation.

Left to right, John, Eileen Hughes, Tricia, Jack Hughes and Muriel Simkin.

Jack was Muriel's brother and Eileen was his wife.

In around 1948 Ted Simkin developed meningitis, an infection of the protective membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord. It can cause life-threatening blood poisoning (septicaemia) and result in permanent damage to the brain or nerves. Although he eventually physically recovered, both my mum and aunt believe it had an impact on his mental condition and from then on, suffered from depression.

On 12th May 1949, my brother David was born. This especially pleased my sister who quickly became assistant mum. Babies do not make good playmates for four-year-old boys. I do not have many memories of this period. I remember being very close to my mum and probably felt a little left out with the arrival of my brother, but this is pure speculation and only have memories of loving him and being upset when he had to stay in hospital as a result of some mysterious illness.

Primary & Junior School

At the age of five I went to school. I remember that when I entered the classroom all the other children were in their seats. This is probably because I was born in June and I was one of the last batch to join the class. I remember feeling extremely nervous, but I was distracted by a giant drawing of a peacock on the blackboard. The teacher was obviously a talented artist. My school reports were not very good. It was not that I was badly behaved, they just complained that they found it difficult to motivate me. On one occasion mum came home from a parents' evening and told me that the teacher said that I did not see things as other children did. She gave the example of the time she asked the class what had three holes in it. I apparently replied pyjama trousers. The teacher suggested I might have a career as a comedian. I was not trying to be funny, that was just the answer that came into my mind.

My mum's values also had a long=term impact on me. My mum taught be not to swear, cheat, lie, hit people, drop litter or write on walls or bus shelters. Although I don't remember my mum telling me about this, but I always thought of her if I was tempted into doing any of these things. The only value that I remember her telling me about was when I was about 16 she told me that it was important as an adult to "pay your way". Mum was a very proud woman and disliked the idea of taking charity. She took this to extremes and as a child I was told I always had to refuse uncles who offered me pocket money if they visited the home. Probably, because of this instruction, I have always felt uncomfortable about receiving gifts from people.

Elizabeth Hughes. Sitting alongside Mrs Hughes and Muriel's baby son

is David's older brother John Simkin. This photograph was taken in the back

garden of the Simkin family home at 42 Bernwell Road, Chingford, Essex in 1949.

There is one incident that took place in primary school that will remain with me for the rest of my life. I must have been about seven at the time. Just before the dinner-break a boy told the teacher that someone had stolen his dinky-toy. The teacher asked us all to open-up our desks to see if it had been placed there by accident. At that moment, the bell went and as I knew the toy was not in my desk, I went out to play.

Ten minutes later a group of boys came running over to me and two of them grabbed my arms. I was told the teacher wanted to see me urgently. When we arrived in the classroom, I was told that the stolen dinky-toy car had been found in my desk. The teacher assumed that I must have been the thief. I pleaded my innocence, but she continued to say how disappointed she was with me. Even my tears did not shake her resolve to punish me for this offence. She was still telling me off when the rest of the class returned for afternoon classes.

Then something amazing happen. A boy, whose name I cannot remember spoke up. This was a surprise as the boy rarely said anything in class. He was also considered to be an odd-ball and was receiving special help in lessons. The boy said that in the morning break he had been looking through the window and saw a boy, who he pointed at, put the dinky-toy in my desk. I cannot remember this boy's name either, but I can still see his face and his horizonal striped t-shirt. My immediate reaction was to wonder if the teacher will believe this boy. However, this was not an issue as the boy immediately confessed. The teacher apologised for accusing me of being a thief. Yet, if that boy had not been looking through that window, I would have been labelled a thief.

This incident had a long-term impact on me. I was brought up not to steal. Throughout my life I have not stolen anything. it is one of the reasons I do not use self-service checkouts. I fear I will make a mistake that would result in me being accused of trying to steal something.

In my adult life I have always been interested in studying possible miscarriages of justice. I am also slow to judge people and if I had been called to serve on a jury, I doubt if I would have voted that they were guilty unless they had made a full confession.

My dad's doctor who was treating him for meningitis recommended that he took up the hobby of fishing. He argued that looking at water would help soothe the brain. As well as going fishing, my father built a pond in the garden and filled it up with goldfish. He especially loved Shubunkins with its spotted colours of red, yellow, orange, blue, white and black in combination with metallic and transparent scales.

At first my dad went on his own, but as soon as I was old enough, around about six, he took me fishing with him. We would get up very early and travelled to the River Lea near Broxbourne, on the Essex/Hertfordshire border. The first thing we did was to go to a café where I had a cup of milky coffee. I suspect this was made with Camp Coffee as I have had a life-long love of this drink.

After catching live bait in the River Lea, we moved to the nearby lakes (gravel pits) at Nazing Meads. These contained large pike. Dad told me that pike was a very dangerous fish and that if you were not careful it would bite your hand off. I know I felt very brave when I landed my first pike. I was very proud of the fact that it weighed 2 lbs. although I now realize this was in fact a very small pike.

Pike are a very unusual fish. Pike can grow to a relatively large size: the average length is about 40–55 cm (16–22 in), with maximum recorded lengths of up to 150 cm (59 in) and published weights of 28.4 kg (63 lb). The young pike feed on small invertebrates. When the body length is 4 to 8 cm (1.6 to 3.1 in), they start feeding on small fish. That is why we used Grayling and Dace as live bait.

The pike is an aggressive species, especially when it comes to feeding. For example, when food sources are scarce, cannibalism develops and feed on smaller pike. This is the reason that pike suffer a fairly high mortality rate. When pike exceed 700 mm (28 in) long, they feed on larger fish. The fish has a distinctive habit of catching its prey sideways in the mouth, immobilising it with its sharp, backward-pointing teeth, and then turning the prey headfirst to swallow it.

You were only allowed to fish for pike between 1st October and 31st March. This meant I got very cold when trying to catch pike. I remember returning home with extremely cold feet. As a child I suffered from chilblains (damage to capillary beds in the skin causing redness, itching and inflammation). My mum used to rub my feet in order to get the circulation going. While doing this she would complain to my dad that I should not be taken out fishing in the depths of winter. He would reply that he was trying to make a man of me. I loved my mum for caring about my welfare but accepted my dad's arguments about the nature of manhood.

Dad and Football

The first football game I took an interest in was a game that took place on 2 nd May 1953, just before my eighth birthday. It was the FA Cup Final between Blackpool and Bolton. We did not have a television and listened to it on the radio. To help me concentrate on the game my dad got me to select a team. He told me about each side, and I chose Blackpool. It was probably because they wore tangerine shirts rather than they had a 38-year-old player, Stanley Matthews, who had never won a cup medal. Blackpool were 3-1 down after 55 minutes, but rallied and won the game, 4-3, Bill Perry scoring the winning goal in the 92nd minute. All that emotion of this late victory got me hooked on the game. We then went out in the garden and replayed the game, with me being Stan Mortenson, who scored a hat-trick, rather than Matthews who made the goals.

I think my father feared that I would become a Blackpool fan. This must have been concerning as he was a passionate Spurs supporter. This was probably the reason why he took me to see my first live game at White Hart Lane on 10th October 1953. The game was against Arsenal and my father took a stool for me to stand on. We went to the front and I was just able to look between the semi-circle metal rings on the top of the wall. The thing that I remembered most was the sound of the crowd. It was the first time that I had heard such a loud noise. My reference book tells me that the attendance was 69,821 and the best of the season.

My position at the front meant that throw-ins became an important feature of the game. This gave me a close-up view of some of the players. I remember the bright red hair of Alex Forbes, the Arsenal wing-half. Colour was obviously important to me as I much preferred the shirts of Arsenal to the boring white of Spurs.

Another thing that struck me was that most of the players looked too old to be playing football. Jimmy Logie was another one who came over to the touchline near me. He seemed extremely old (the record books say he was 33 at the time). Logie was also wearing long shorts that covered his knees. Spurs also had some old players. Ron Burgess, 36, was virtually bald (not shaven) and Bill Nicholson, aged 34, was nearing the end of his career and was later the manager of the great 1960-61 Spurs team. The other player that stood out was Len Duquemin. Physically he was a fine specimen of a man. He also looked and sounded foreign. He in fact came from Guernsey and during the German occupation of the Channel Islands during the Second World War hid in a Catholic monastery.

My father wanted to buy me a Spurs football shirt for Christmas. I said I preferred to have a Blackpool shirt. He said that was impossible and instead bought me an Arsenal shirt. Looking back that was an extremely cruel thing for me to do. I am amazed that he let me get away with it. I know that I bought my grandson a West Ham pair of pyjamas at the age of three before buying him the full kit a year later. I never gave him any choice in the matter. I always saw my dad as a rather stern man but over this issue he seems to have been a bit of a softie.

In the summer we often went fishing on a Saturday. In the winter, we went to see Spurs at home and when they were playing away, we went fishing on the River Lea, and the nearby lakes at Nazing Meads (you were only allowed to fish for pike in the winter). I do not remember my mum complaining about this arrangement. Much later, my sister said she was extremely angry that I was someone who was having all the treats. When my brother was old enough, he also came fishing with us, but Tricia never did. Maybe she was asked and refused. I wished I had asked her this question when she was alive. This is the same with all those loved ones who have died. So many questions that will never be answered.

Although I spent the weekends with my dad watching football and going fishing, for the rest of the week, I was very much a mummy's boy. At school I found it difficult to make friends and relied too much on my older sister to look after me. I never played in the street and was happy just being with my mum. That was until one day, at the beginning of the Easter holidays, when I was about seven, she put me in the front garden and closed the door behind me. I was terribly shocked by this action as my mother was always so kind and although I am probably wrong about this, it is the only occasion I can remember her punishing me. Of course, she was being cruel to be kind and in doing so had a major impact on my personality. However, I did not feel this way at the time and still retain the picture of me hammering with my fists on the front door.

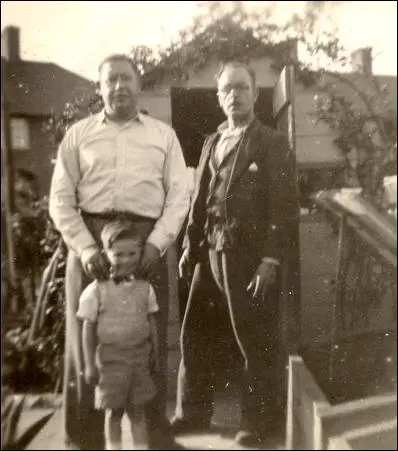

alongside a neighbour, Arthur Whitehead in about 1953. When this photograph

was taken the family were living at 42 Bernwell Road, Chingford, Essex.

Eventually, I gave up trying to get back into the house and wandered into the street outside. This would be unthinkable today, but in the early 1950s, council estates were virtually carless and the streets were the property of children. If a car did venture down our road it was always driven very slowly. One of our neighbours did have a car outside their house but it never moved because the owner could not afford to get it repaired. A couple of families had motorbikes with sidecars, but they always entered the road very carefully.

In a few minutes I was playing with Janet and Johnny Morris. They were twins but were not identical. Johnny had bright red hair whereas Janet was very dark. They were slightly younger than me, but we soon became great friends. After that I was out every day. A few months later, I was allowed to invite Janet and Johnny Morris to my birthday party. While my mother was in the kitchen Janet told me that she did not have a birthday present to give me, but she was willing to show me her bottom. Before I had the opportunity to say anything, she turned around, and pulled down her knickers. Up until that time I had no idea that such an action could be interpreted as a gift, and I forgot to say thank you. In fact, to my eternal shame, when my mum returned, I told her what Janet had done. Mum did not tell her off and so I just assumed it was alright to do this. In fact, when I got older, I always thought a young woman undressing in front of me was one of the best presents I could be given. Anyway, because of my ungratefulness, Janet never showed me her bottom again. A few months later we moved to another council estate, and I never saw Janet again. It was only then that I realised I loved Janet and for years I used to fantasize about bumping into her while traveling. It was not to be, but Janet had opened a door to a world I could not enter until several years later.

in Chingford, Essex, during the celebrations marking the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

in June 1953. Later, my sistor would tear-up this picture, but was restored in photoshop.

In 1954 we moved from Bernwell Road in Chingford to Audley Gardens in Debden. During the Second World War the London County Council had purchased 644 acres of land in the parish of Loughton on the edge of Epping Forest with the intention of building new houses for the people living in Bethnal Green who had lost their houses during the Blitz. The Debden Estate was constructed between 1947 and 1952 and we had replaced one of the many families who had returned to the East End as they missed the extended family and the area's sense of community.

I was not aware of it at the time but two sociologists, Peter Willmott and Michael Young, had decided to carry out a study of this new model council estate. Their book, Family and Kinship in East London, was first published in 1957. The book describes how working-class family life changed when families moved from Bethnal Green to Debden (they called it Greenleigh in the book) in rural Essex. The book has been acknowledged as being one of the most influential sociological studies of the twentieth century and helped to explain the difficulties people had moving from industrial cities to live on modern housing estates in the countryside.

Interestingly, twenty-years later, I studied Family and Kinship in East London when I was at the Open University, an institution first suggested by Michael Young, one of its authors. Young, was responsible for drafting "Let Us Face the Future", Labour's manifesto for the 1945 General Election. He founded or helped establish a number of socially useful organisations. These include the Consumers' Association, Which?, the National Consumer Council, the National Extension College and the Open College of the Arts. Not all of Michael Young's creations were a great success as he is also the father of Toby Young.

Willmott and Young described the Debden estate as providing "up-to-date semi-detached residences" that were "each enclosed by a fence, each with its little patch of flower garden at front and larger patch of vegetable garden at back, each with expansive front windows covered over with net curtains; all built, owned and guarded by a single responsible owner." These new estates gave the working-class dignity and reinforced the idea they were respectable members of the community.

in the back garden at 27 Audley Gardens (1955)

I loved the estate as it was surrounded by attractive countryside that gave me a great sense of freedom. Audley Gardens was a cul-de-sac (we called it a banjo). In between two rows of houses, a grass field had been left, a sort of working-class village green. This provided us with a football pitch on our doorstep. We formed a football team and played against other street teams. I had a book where I kept a record of all the games and the people who scored the goals (I was the main striker and so this gave me a great deal pleasure). It was my most successful time as a footballer (I was not good enough to get into the school team.) The reason we did so well was our playmaker, Roy Huke. He was so good that after he left school, he joined Tottenham Hotspur, but unfortunately never made it into the first team.

Death of Dad

Dad was a 'plastic moulder' at the 'Ever Ready' Electrical Battery works in Edmonton, North-East London. He worked in shifts, sometimes working through the night, returning to his home to catch up on his sleep during the daytime. When we lived in Chingford, he was only 4.5 miles from his work, now it was 10.9 miles. It was decided the only way he could manage it was buying a Lambretta motor scooter. The money was raised by borrowing the money from the boss of my mother's brother, Jack.

the backyard of his house in Audley Gardens.

I loved living in Debden. Moving from Chingford had not caused me too many difficulties. My shyness had not returned, and I gradually forgot Janet Morris, concentrating more on football than girls. I also liked my new school, but my academic abilities had not improved. I was now in my last year of junior school and my behaviour must have been reasonably good because they made me a prefect. They gave me a green badge in the shape of a shield with the word "Prefect" in gold lettering. When I heard the news I raced home to tell my parents. My mum seemed pleased, but it was my dad's approval I really wanted. He was upstairs shaving. He was on night-shift and was getting ready to go to work.

What happened next was to change me for ever. To my great surprise he did not seem to be happy about me becoming a prefect. He told me about how some people change for the worse when they are placed in authority. This view was based on his experiences in the army and life in the factory since the war. I was fairly confused by his comments. I expected him to say he was proud of me. I cannot remember him ever saying this, but to be fair, I do not remember him criticising me very much either. As I write this 70 years later, these are the only words I can remember him saying to me. The only political opinion he had that I had heard directly from him (over the years my mum told me about the strong views he had over a wide variety of subjects, especially religion – he was a committed atheist). It changed me because from that point on I was always suspicious of those in authority. To be otherwise I would have felt I was being disloyal to my dad.

Dad's life had not turned out as he wanted. Mum said that he was an extremely happy man in the 1930s, but the war had changed his personality and he had never come to terms with the change in his occupation. I have memories of him sitting in his armchair with his book on his lap, staring at his raised left hand. It was now several shades of dark blue and the fingers appeared to be rotting away. I did not know it at the time but apparently his doctor at Roehampton Hospital had told him that further amputations would be needed. Dad was suffering from depression. I cannot remember him losing his temper with me, but I do not remember him not smiling at me very often. He seemed to be withdrawing from life.

You only remember a few isolated incidents from childhood. Usually, you are aware of why these memories are important. However, sometimes, it is a mystery why these images keep on returning. This is true of the 5th November 1955. We had a street bonfire and I was with my mates when Tricia came up to me to say that dad was about to start a firework display in the garden. For some reasons I said I would prefer watching the bonfire and the other boys who had their fireworks. I cannot remember if my dad said anything when I returned home. Although I always feel an overwhelming feeling of guilt whenever I remember that night. Have I suppressed the memory of these comments? I do not think so, but he might have given me one of those looks of disapproval that I always found so disturbing. It is a family trait. Sometimes my brother gives me the same look. The women in my life have complained that I do the same thing. I am sure my father's stares were worse than I could do. It was not only the look of disapproval but a deep sadness of someone who had lost all optimism.

was suffering from depression at the time.

I woke up in the early hours of the morning of Tuesday, 16th October 1956, to the sounds of crying. I opened the bedroom door to find Tricia leaning over the bannister crying. My mother was also crying and was on the stairs and giving my sister instructions on dealing with David and myself. At the bottom of the stairs was mum's brother Jack. He was the only family member with a car and lived close-by. After they had gone Tricia told me that dad had been involved in an accident on the way the work that morning and Uncle Jack was taking my mum to the hospital.

I did not join in the crying, but I did not go back to bed and eventually got ready for school. I always met my friends on the green before walking to school. The green was higher than my house and while standing there I saw my uncle's car return and park outside our house. As they were walking along the path, the woman who lived next door came out and said something to my mum. I could not hear what my mum's reply was, but the woman turned round holding her face and shaking her head. Instead of running back home I walked to school.

I do not remember being upset at school. I definitely did not tell anyone about my fears of what had happened. It was as if I had erased the memories of that painful morning. I was brought back to reality on my walk back home. On the corner of my road was my dad's brother, Bill. He was wearing a dark suit and his black tie was blowing in the wind like a flag. I do not remember him telling me that dad was dead. He did not need to. My mum opened the door. My first words were, "What am I going to do mum, who is going to take me to football now." My mum turned her head away from me and replied, "But, what am I going to do now." If I had been older, I would have been better able to hide my selfishness.

I was led away to my bedroom. The curtains were closed, and I was told to lie down in the dark. I stayed there for several hours in silence. I did not cry. Apparently, this is not uncommon reaction in young children on the death of a parent. The emotion is too powerful for them to deal with it at the time it happens. Grief has to be dealt with in stages.

Later I learnt that dad drove his Vespa straight under the wheels of a lorry and suffered serious head injuries. At the inquest the driver, who cried throughout his testimony, was accused of falling asleep at the wheel. This he denied and insisted that it was my dad's fault. My mum believed the man and suspected that my dad might have committed suicide as he was extremely depressed at the time because of an upcoming operation on his hand that might have made him unemployable. I do not want to believe that. I would not like to have a father who did not take into consideration the impact his death would have on the driver of the other vehicle.

The next day, on the way to school, Roger Lyons said he was sorry to hear that my dad had been killed. My first reaction was to say, don't tell anyone else that my dad was dead. I was not ashamed he was dead, but I was afraid that if anyone mentioned it at school I would cry. I remember worrying about this when I started work at fifteen. I thought they would ask me what my dad did for a living and expected that I would burst into tears. Can you imagine the embarrassment of that on your first day of entering the adult world? However, I overestimated the amount of interest people have in you and I did not have to worry about such things.

Roger Lyons had lost both his parents in a road accident a few months earlier. His father and mother were on a motorbike and the three children in the sidecar were unhurt. His grandmother moved into the house to look after the children. The headline in the local newspaper the week of my dad's death was "Death Street".

My crying began several months later. My dad's brother Bill visited us. He told me that my mum was short of money and that I needed to get a job delivering newspapers. At this point I burst into tears and I was led away to lie down in my bedroom. I cried because Bill was trying to act like my dad. It was also the realisation that my dad was never coming back. I also knew that I did not want anyone else to be my dad. Several years later, Bill's wife, Winnie, died of lung cancer. He started visiting my mum and eventually he became my stepfather. By this time, I was married and although I had little respect for him, I was pleased that my mum had some company in her final years. Mum always needed someone to look after, a service us children could no longer provide.

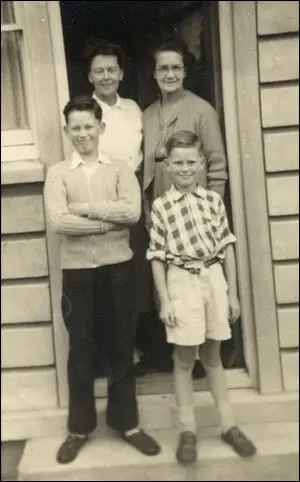

Front Row: Gordon (a visitor) and David (8) in the back garden at Audley Gardens.

I had two uncles who were also Spurs supporters, but only on one occasion did one of them take me to a match. To be fair, Uncle Bill did let me select the game. It was Spurs v Blackpool on 27 th April 1957. Spurs won 2-1, with both goals being scored by Tommy Harmer. I should have been happy, but I think I was upset by the result. I stayed over and Winnie cooked Sunday lunch. Bill and Winnie were childless and had no idea of the fads of young people. It was piled high with vegetables and was swimming in gravy. This was different from the way my mum prepared the food. My mum had told me that I must eat everything I was given. I tried but was physically sick in front of them. I was never again invited to see another Spurs game. From that day on I stopped supporting Spurs and have had problems eating vegetables.

The death of my father changed my personality. If it had not happened, I would have been a different person. It changed my relationship with my mum. After my sister went away to be trained as a nurse, my mum talked to me a lot about the problems of trying to bring up a family without a husband. I remember coming home from school and finding her crying. The man from the National Assistance Board had just left. He had told her she should send the rented television back and move to a smaller, cheaper, council house.

We were poor before my dad died, now we were extremely poor. I do not remember being hungry but was aware mum was unable to buy us new clothes. Everything I wore was either knitted or donations from family and friends that had to be altered. Mum did her best, but they never looked right and as soon as I started work at fifteen, I spent a large proportion of my money (I gave half to my mum) on clothes. Whereas the other men went to work in jeans, I wore a suit. I did not mind them laughing, I knew what I had to do for my mental health.

The daily discussion on family financial matters changes your outlook on life. You get a sense of responsibility that is unusual for someone as young as that. It is something that never goes away. I am not complaining, I am pleased with that kind of personality. In a way, I became mum's temporary husband. She also wanted me to become a father to my brother. I enjoyed the role and got great pleasure in his successes. I watched him play football for the school team and took him to see West Ham play at Upton Park. We now talk about football in a similar way to other fathers and sons. A constant cause of stress but also the occasional intense feeling of pleasure.

One of the major aspects of losing a father at such an early age is the absence of an authority figure to argue with. Dad was a dominant figure in the family when he was alive. I am sure there would have been major conflicts during my teenage years. In many ways, a dead father can have more control over you than a live one. Before making important decisions I often ask myself what dad would think. Although I do not believe in an afterlife, psychologically, I still want his approval.

Secondary School

At the age of five I went to school. I remember that when I entered the classroom all the other children were in their seats. This is probably because I was born in June, and I was one of the last batch of kids to join the class. I remember feeling extremely nervous, but I was distracted by a giant drawing of a peacock on the blackboard. The teacher was obviously a talented artist. My school reports were not impressive. It was not that I was badly behaved, they just complained that they found it difficult to motivate me. On one occasion mum came home from a parents' evening and told me that the teacher said that I did not see things as other children did. She gave the example of the time she asked the class what had three holes in it. I apparently replied: "pyjama trousers". The teacher suggested I might have a career as a comedian. I was not trying to be funny, that was just the answer that came into my mind.

Although I don't remember taking it I failed my 11+ exam and went to the secondary modern, Fairmead School in Loughton. I was clearly not unlucky to fail the exam because I was not in the top group in my new school. I do not remember the names of my teachers at Fairmead. None of them inspired me to take an interest in the subject they were teaching. I only recall one lesson that I had at Fairmead. It was an English lesson and the teacher told us to write a short story. This pleased me as I always had a vivid imagination. I can't recollect what the story was about, but I thought it was really good. I handed my book in and waited anxiously for it to be returned. I was extremely disappointed when she handed the book back as under the story all I got was a red tick without a comment on my first venture into creative writing. After that I did not bother too much about my schoolwork.

John Simkin and David Simkin at 27 Audley Gardens, Debden, Loughton, Essexin 1957.

When I was 13 years old, I was told that if my work did not improve, I would be dropped to a lower group. This really upset me for two reasons. I was in love with Janet Simpkins, a fellow classmate and had just started negotiations about our possible relationship with her best friend, Valerie Wade.

The other reason was I loved talking to the two girls who sat in front of me. Despite my renewed efforts I was still demoted to a lower class. (Tragically both those girls who sat in front of me were killed on 4th November 1967 when they were returning to England from a holiday in Spain on Iberia Flight 062 when it crashed at Blackdown, West Sussex, killing all 37 people on board.)

The following year my mother decided to move the family to Dagenham. I now went to Campbell Road Secondary Boys School. It did not have "Modern" in its name because you could not stay on until 16 to take ‘O' levels) at this school. My form teacher at Campbell, Mr Brown was an amazing character, but I don't remember him teaching us anything at all. He wore a three-piece suit and had an accent that I had never heard before (I later realised he had been educated in a public-school). Teaching was virtually impossible at our school. It was more an issue of crowd-control. He would entertain us with stories of the war. He told us he was an officer in military intelligence and spent most of his time was spend interviewing German prisoners of war. Mr. Brown claimed, and we believed him, that because of techniques he had learnt from the military, he could make people cry by just looking at them. To cry in front of your mates was one of your most feared experiences and therefore was a very good control device. Therefore, we were usually well-behaved although we never saw him make any boy cry by looking at him.

On reflection, I am not sure he believed this tactic would work with all kids. For example, we had two boys in my class who in the playground were the toughest in the school. I remember one incident when they stripped two boys completely naked and pushed them up against the railings that separated the playground of our school and the neighbouring girl's school. (I am sure this set-up gave both boys and girls an unhealthy interest in the opposite sex.) These two tough boys were rarely in lessons. Mr. Brown had a large room behind the classroom with a small printing-machine in it. These two boys spent every day in this room carrying out printing jobs. Brown told us the best job we could ever expect to have, was in the printing trade and he was able to give us training in this. Working in the print room was highly prized and I am sure it was enough to keep these two boys under control.

Over the years I have often wondered what Mr. Brown was doing in our run-down school. I reject the idea that he was a missionary teacher bringing education to the working-classes because he never really tried to teach us anything. I eventually came to believe that Mr. Brown must have carried out a terrible offence as a teacher in a public school. Unable to work in that sector, he was forced to work in a school who would take anybody willing to teach in our school. .

Mr. Brown did have his sensitive side. He once asked me what my father did. When I told him, my father was dead, he came close to tears. After that he seemed to treat me with tenderness. Occasionally he would haunch down beside me and engage in conversation. I remember one day he came to talk to me after he found out that I played football. He seemed very surprised that I played such a rough game. He clearly saw me as a soft boy. I was but I was never bullied. Playing football helped but it was my use of language was the main reason. Bullies are always afraid of words. They are only comfortable in the physical world.

The best teacher at the school was Mr. Gant, but it was only in my last term before I left school at fifteen that I met him. He took a series of lessons preparing us for the world of work. This involved discussions on current events. For the first time in my life, a teacher asked me what I thought about something. I loved this new approach and although I knew nothing about current events, I was very keen to talk. Only one other boy was interested in getting involved in this debate. Mr. Gant was clearly pleased by my willingness to contribute as he gave me reassuring smiles (recalled in vivid detail as I write this) and did not tell me I was talking nonsense, even though I probably was guilty of this offence.

Apprentice

A few months before I was due to leave school our next-door neighbour asked my mother if she wanted help in finding me a job. Aware that my father was dead she was willing to use her influence to help me. That was something that happened in working-class areas in the 1950s. There was a great sense of community on these council estates that had been built after the war to house people who had been victims of the Blitz. Soon after my father's death one neighbour took me on holiday to Somerset. This was the first time I had been on holiday. Before that we were restricted to going on daytrips to Southend. Another neighbour took me with his son, Roy Huke, to watch Spurs play at White Hart Lane. He had a motorbike and I had to sit in the sidecar with his son. After the game we had tea with Roy's grandparents in Tottingham.

This neighbour who offered to help with a job had a son-in-law named Reg Pratt. He was a sales representative in the print trade and said he was willing to use his influence to get me a much sort after apprenticeship in the industry. Eventually I was told I had an interview with George Duffield, a small printing works in Barking. The manager of the company, Bill Turnbull, told me that as far as he was concerned, he was willing to employ me but first we had to check with the Father of the Chapel (FOC). This was the name given to the head of the union at the factory. At this time the printing trade was a closed shop (a union agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only). The union also had an agreement that restricted the number of apprentices that could be trained in the industry. This is one of the main reasons why printers were so highly paid during this period because they were always in short supply.

The FOC agreed to my employment and soon after my 15th birthday, on the Monday after leaving school, I began my first day of work. I was assigned to work under Charlie Williams, the guillotine operator. Bill Kelley, the foreman, took me to meet Charlie and I was somewhat disturbed by the fact that when he went to shake my hand, I noticed he had no fingers on his hand. I later discovered that several years previously, the guillotine had overrun and as he was taken out the trimmed ream of paper, the blade had cut off the fingers of his right-hand. The guillotine in the George Duffield factory had a guard that came out as the blade came down to cut the paper so it was in theory impossible to lose your fingers in such a way. Even so, for the first few months of using the guillotine I had that vision of Charlie's fingerless hand.

My main job at first was packing printed materials in brown paper parcels. This was incredibly boring and looked forward to my other job of making the tea for the workers in the factory. The tea-making facilities were in the compositing department. I soon became friendly with one of the compositors, Bob Clarke. In those days, compositors used to set type by hand and because of the noise of the printing machines it was the only place in the factory where you could have a decent conversation. Making the tea gave me the opportunity to talk to him about a wide variety of topics. At the end of the day, we also walked to the bus stop together.

Bob was at this time in his mid-thirties. I soon discovered he had a son, but he died soon after he was born. His wife, Iris, never recovered from this tragedy, and although she said she wanted children, she never agreed to stop using birth-control. I did not realise it at the time, but Bob had psychologically adopted me as a son, and he had become my surrogate father. Bob would constantly ask me what I thought about the political issues of the time. It embarrassed me that I tended to give emotional rather than factual answers. To improve my knowledge of politics I began to buy the Daily Herald. It was originally started in 1912 to support the Labour Party and by 1922 was taken over by the TUC. In the 1930s it was the UK largest selling newspaper but by 1960 it was owned by Odhams Press and was struggling to survive with less than 3% of all newspaper sales. It still supported the Labour Party and took politics slightly more seriously than the other left of centre newspaper, the Daily Mirror.

Bob never disagreed with the answers I gave him. Instead, he asked follow-up questions that tested the logic of my original answer. Bob used the same approach to education as the Greek philosopher, Socrates. I am sure Bob had never heard of Socrates because his education had been no better than mine. Socrates pointed out that "the arguments never come out of me; they always come from the person I am talking with". He described himself as an intellectual midwife, whose questioning delivers the thoughts of others into the light of day.

Bob never told me that my answers to his questions were inadequate, but I knew they were. I soon realised that reading a newspaper was not enough as they rarely gave enough background information about the subject. I lacked a historical perspective. I joined the local library and started borrowing books that would help me with my answers. At first, they were about post-war politics but later I became interested in the world before 1945.

Bob was a great teacher because he asked me open-ended questions. My teachers at school were only interested in providing answers to closed questions. I used to find this very boring. Later I did a psychological test that showed I was a divergent thinker. The concept was first coined by J. P. Guildford in 1956. Divergent thinking is a thought process used to generate creative ideas by exploring many possible solutions. Schools are mainly interested in convergent thinking, which follows a particular set of logical steps to arrive at one solution.

However, the main reason Bob was able to become a great teacher was that he was really interested in me as an individual. Except for Mr Gant, in those final few weeks of my school-life, none of my teachers had been interested in my opinions.

Every lunch time the men would sit in a circle in the main print room and eat their sandwiches together. They also debated all the political issues of the time. Bob Clarke and Bill Parrish, both impressed me with the way they talked about politics. It was 1960 and the men were critical of a Tory government that had been in power for nine years. Most of the men held left of centre opinions but one man, Geoff Barling, who was in his late fifties, had very conservative views. This was not only about politics, but he also complained bitterly about recent developments in society. He was especially opposed to the movement towards more sexual freedom. Although he was a married man he seemed to be repulsed by all sexual activity. His outbursts had little impact on my thinking, and I had little difficulty in agreeing with the older apprentices on the subject.

Falling in Love

At the age of sixteen I joined Great Warley F.C.. I should point out it was named after the village of Great Warley rather than from past glories. I was a very average footballer, and I never made the first-team. However, the manager did make me at seventeen the captain of the second-team. This was a strange decision as the rest of the team were older than me. I suspect he did it to give me confidence because at the time I was a fairly shy person. It worked and I gradually became more assertive, and I also became a better player, but never good enough for the first-team. It was also the beginning of the conviction that I was a good leader who always knew what was the best thing to do for the team. In many ways it encouraged too much confidence in my ability to make good decisions, however, it did mark a change in my personality that remained with me for the rest of my life.

On one occasion the manager regretted his decision to make me captain. We reached a cup-final and when we were one down, we got a penalty. The manager's son, who normally played for the first-team, came up to me and said he should take it as he had never missed a penalty in his life. I perversely ignored his request and handed the ball to our centre-forward. On reflection I made this decision because he was always laughing and appeared not to suffer from nerves. Whereas the manager's son seemed very uptight. Anyway, my logic was deeply flawed because he blasted the ball over the crossbar, and we lost 1-0.

In April 1963, Jimmy Sewell, a fellow member of the Great Warley football team, asked me if I would go with him on Saturday night to the Catholic youth club disco on the Harold Hill council estate. I explained I was not a Catholic, but he said that did not matter as he would tell them I was his cousin who lived some distance away but was staying with him for the weekend. My mother had brought me up not to lie and not telling the truth has always caused me psychological problems. However, if he was willing to lie for me, I would agree to go.

Soon after I entered the hall I was attracted to a slim, blonde, young woman, dancing with her dark-haired girlfriend. She seemed to be the same person who I saw on the railway station when I attended South East Essex Technical College. I did this one day a week as part of my apprenticeship and gave me the opportunity to do my City and Guilds exams. Unfortunately, she was always on the opposite platform going in the other direction. I told myself if I was on the same platform as her, I would have spoken to her. However, what would I have said? Now I had an excuse to talk to her. I could ask her to dance. Jimmy agreed to take care of her friend and both said yes. It was only a brief dance before we became engaged in a long conversation. She said her name was Julie. In fact, it was really Judith but at the time she thought that name was old-fashioned. Despite the objections of her mother, for the first few years of our relationship, I called her Julie. However, my mother called her Julie until she died forty-six years later.

Julie was not the woman on the station platform but part of me never accepted that fact. It was like my fantasy had turned into reality. Julie was just as attractive as the woman on the platform. It was like I had fallen in love with her before I met her. I walked her home and arranged to see her the next day. As a Catholic she had to go to church next morning. Instead of going to church with the rest of the family at midday she went to the early service at St Dominics, and we went for a walk in the countryside on the edge of the Harold Hill estate.

For me it was love at first sight. Julie took a little longer to realise she was in love. In fact, she seemed deeply shocked by the early declaration of my feelings. Initially, my feelings towards Julie was mainly about sexual attraction, but it was also about the pleasure I got from talking to her. In the words of Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Our true love is he or she who brings to life in us our real life." When I went to work on Monday morning, I told Bob Clarke that I was going to marry the woman I met at the Disco on Saturday.

Most Sundays we went on long walks in the neighbouring countryside. The Harold Hill estate was conceived in the Greater London Plan of 1944 to alleviate housing shortages in Inner London caused by the Blitz. Harold Hill was built on the Dagnam Park house and grounds, and the estate was surrounded by parklands, woods and farm fields. On one of our walks soon after we met, she asked me how much money I had saved up. "Nothing" I replied. My excuse was that I gave half my small wage to my widowed mother. Julie had already saved up £200 and she told me that if I wanted to marry her, I had better start saving.

I saw Julie several times a week. On Saturday we went dancing at the Basildon Locarno or the Ilford Palais. I was not a confident dancer, and I usually only took to the floor during "Dreamtime" when the lights were lowered, and they played slow songs. At Julie's request we took ballroom dancing lessons, but these came to an end when the teacher declared I was "unteachable".

Sometimes we went to the cinema on a Saturday night. One of the first films we went to see was A Kind of Loving, a film based on a novel by Stan Barstow. Vic Brown is a draughtsman in a Manchester factory who sleeps with typist Ingrid Rothwell. She falls in love with him, but Vic does not feel the same way about her. When he learns he has made her pregnant Vic proposes marriage and the couple move in with Ingrid's domineering mother. Ingrid has a miscarriage and Vic feels he has been trapped in a loveless marriage. The film finishes with Vic and Ingrid considering the possibility of making do with "a kind of loving".

I still remember the long conversation with Julie about the film that started on the bus and the long walk-up Straight Road before arriving at her home in Daventry Road. Although, unlike, Vic and Ingrid, we both loved each other, we were determined not to get married before we were ready for such a commitment. This was reinforced by Julie's mother constantly telling us about unmarried young women on the estate getting pregnant and letting their families down.

Before I arrived on the scene Julie spent a lot of time with her friend Denise. She was with Denise when I met Julie at the Catholic Youth Club. For a few weeks we used to go to pubs together with Denise and Jimmy Sewell. The relationship did not last, and we lost contact with Denise until one day, many months later, she turned up at Julie's home. Denise told Julie she was pregnant, and the young man refused to marry her. She claimed that her life had been ruined. Julie never saw Denise again but that brief meeting brought back the conversation we had after watching A Kind of Loving. It also encouraged us to keep on saving for the wedding that would take place the week after I completed my apprenticeship in the print trade.

Meeting the woman who you are going to marry clearly changes your life, but in my case, it deeply influenced my personality. At eighteen I knew I was loved by my mother but was not certain anybody else would love me. To fall passionately in love with someone who feels the same way about you is the most fantastic feeling possible. It also gave me a belief in myself that remains today. I psychologically linked passion with success. I also developed the idea that if you wanted something enough, you had a very good chance of getting it.