Winston Churchill: 1927-1939

One of the results of this Trade Disputes and Trade Union Act was that trade union membership fell below the 5,000,000 mark for the first time since 1926. However, despite its victory over the trade union movement, the public turned against the Conservative Party. Over the next three years the Labour Party won all the thirteen by-elections that took place. Stanley Baldwin considered offering government help to relieving distress in high unemployment areas but Winston Churchill, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, insisted that "we must harden our hearts". (1)

Winston Churchill was a great admirer of Benito Mussolini and welcomed both his anti-socialism and his authoritarian way of organising and disciplining the Italians. He visited the country in January 1927 and wrote to his wife, Clementine Churchill, about his first impressions of Mussolini's Italy: "This country gives the impression of discipline, order, goodwill, smiling faces. A happy strict school... The Fascists have been saluting in their impressive manner all over the place." (2)

Churchill met Mussolini and gave a very positive account of him at a press conference held in Rome. Churchill claimed he had been "charmed" by his "gentle and simple bearing" and praised the way "he thought of nothing but the lasting good... of the Italian people." He added that it was "quite absurd to suggest that the Italian Government does not stand upon a popular basis or that it is not upheld by the active and practical assent of the great masses." Finally, he addressed the suppression of left-wing political parties: "If I had been an Italian, I am sure that I should have been whole-heartedly with you from the start to the finish in your triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism." (3)

Churchill shared Mussolini's opinions on the problems of democracy. Churchill wrote: "All experience goes to show that once the vote has been given to everyone and what is called full democracy has been achieved, the whole political system is very speedily broken up and swept away." (4) Churchill told his son that democracy might destroy past achievements and that future historians would probably record "that within a generation of the poor silly people all getting the votes they clamoured for they squandered the treasure which five centuries of wisdom and victory had amassed." (5)

Stanley Baldwin, wanted to change the image of the Conservative Party to make it appear a less right-wing organisation. In March 1927 He suggested to his Cabinet that the government should propose legislation for the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party. (6)

Churchill was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. He lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. (7)

There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. Many of the women who had fought for this right were now dead including Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Barbara Bodichon, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Constance Lytton and Emmeline Pankhurst. Millicent Fawcett, the leader of the NUWSS during the campaign for the vote, was still alive and had the pleasure of attending Parliament to see the vote take place. That night she wrote in her diary that it was almost exactly 61 years ago since she heard John Stuart Mill introduce his suffrage amendment to the Reform Bill on May 20th, 1867." (8)

In January 1929, 1,433,000 people in Britain were out of work. Churchill was widely blamed for the poor state of the economy. However, he refused to take action to reduce the problem. He told Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, that unemployment was not a political issue for the Conservatives: "Unemployment was confined to certain areas, which would go against the Government anyhow, but it was not sufficiently spread to have a universal damaging influence all over the country." (9)

Churchill resisted attempts by his colleagues who suggested he took action to reduce unemployment. In his opinion the British economic position was sound and that there was "a more contented people and a better standard of living for the wage earners than at any other time in our own history". He thought the Government should not allow itself to be "disparaged abroad and demoralised at home" by the unemployment figures". This was because they did not represent genuine unemployment,only "a special culture developed by the post-war extensions of the original Unemployment Insurance Act." He told the Cabinet that "it is to be hoped that we shall not let ourselves be drawn by panic or electioneering into unsound schemes to cure unemployment". (10)

1929 General Election

Baldwin was urged by some economists to take measures that would protect the depressed iron and steel industry. Baldwin ruled this out owing to the pledge against protection which had been made at the 1924 election. Agriculture was in an even worse condition, and here again the government could offer little assistance without reopening the dangerous tariff issue. Baldwin was considered to be a popular prime minister and he fully expected to win the general election that was to take place on 30th May, 1929. (11)

In its manifesto the Conservative Party blamed the General Strike for the country's economic problems. "Trade suffered a severe set-back owing to the General Strike, and the industrial troubles of 1926. In the last two years it has made a remarkable recovery. In the insured industries, other than the coal mining industry, there are now 800,000 more people employed and 125,000 fewer unemployed than when we assumed office... This recovery has been achieved by the combined efforts of our people assisted by the Government's policy of helping industry to help itself. The establishment of stable conditions has given industry confidence and opportunity." (12)

The Labour Party attacked the record of Baldwin's government: "By its inaction during four critical years it has multiplied our difficulties and increased our dangers. Unemployment is more acute than when Labour left office.... The Government's further record is that it has helped its friends by remissions of taxation, whilst it has robbed the funds of the workers' National Health Insurance Societies, reduced Unemployment Benefits, and thrown thousands of workless men and women on to the Poor Law. The Tory Government has added £38,000,000 to indirect taxation, which is an increasing burden on the wage-earners, shop-keepers and lower middle classes." (13)

In a speech made during the campaign Winston Churchill told the Anti-Socialist and Anti-Communist Union (one of his favourite organisations) gathered at the Queen's Hall that if Labour won "they would be bound to bring back the Russian Bolsheviks, who will immediately get busy in the mines and the factories, as well as among the armed forces, planning another general strike" and the Government would be manipulated by "a small secret international junta". (14)

This was Churchill's theme throughout the campaign. On 15th April 1929 he delivered his fifth Budget and Neville Chamberlain described how he "kept the House fascinated and enthralled by its wit, audacity, adroitness and power". Two weeks later, as part of the election campaign, Churchill made his first radio broadcast. He urged his listeners to vote Conservative: "Avoid chops and changes of policy; avoid thimble-riggers and three-card-trick men; avoid all needless borrowings; and above all avoid, as you would the smallpox, class warfare and violent political strife." (15)

In the 1929 General Election on 30th May the Conservatives won 8,656,000 votes (38%), the Labour Party 8,309,000 (37%) and the Liberals 5,309,000 (23%). However, the bias of the system worked in Labour's favour, and in the House of Commons the party won 287 seats, the Conservatives 261 and the Liberals 59. The Conservatives lost 150 seats and became for the first time a smaller parliamentary party than Labour. Thomas Jones was with Churchill when the results came in. "At one desk sat Winston... sipping whisky and soda, getting redder and redder, rising and going out to glare at the tape machine himself, hunching his shoulders, bowing his head like a bull about to charge. As Labour gain after Labour gain was announced, Winston became more and more flushed with anger, left his seat and contronted the machine in the passage; with his shoulders hunched he glared at the figures, tore the sheets and behaved as though if any more Labour gains came along he would smash the whole apparatus. His ejaculations to the surrounding staff were quite unprintable." (16)

David Lloyd George, the leader of the Liberals, admitted that his campaign to increase public spending in order to reduce unemployment, had been unsuccessful but claimed he held the balance of power: "It would be silly to pretend that we have realised our expectations. It looks for the moment as if we still hold the balance." However, both Baldwin and MacDonald refused to form a coalition government with Lloyd George. Baldwin resigned and once again MacDonald agreed to form a minority government. (17)

Winston Churchill was furious with both David Lloyd George and Stanley Baldwin because they had allowed the Labour Party to form the new government. Lloyd George argued that he had no choice but to do this as his manifesto promises were much closer to the policies of the Labour Party. Churchill replied: "Never mind, you have done your best, and if Britain alone among modern States chooses to cast away her rights, her interests and her strength, she must learn by bitter experience." (18)

Churchill hoped that Baldwin would be removed and he would replace him as leader of the Conservative Party. He feared that the party would select someone on the left of the party such as Neville Chamberlain. While visiting Canada he wrote to Clementine Churchill that if Chamberlain "or anyone else of that kind" was made leader "I will clear out of politics and see if I cannot make you and the kittens a little more comfortable before I die." He explained that his thoughts were on the premiership. "Only one goal attracts me, and if that were barred I should quit the dreary field for pastures new." (19)

Churchill was in New York City on 29th October, 1929, when the Wall Street Crash took place. His own shareholdings plummeted and his losses were in excess of £10,000, more than £600,000 in the money values of 2018. The following day he saw from his bedroom window "a gentleman cast himself down fifteen storeys and was dashed to pieces, causing a wild commotion and the arrival of the fire brigade". Later that day he visited the floor of the Stock Exchange where members walked "like a slow-motion picture of a disturbed ant heap, offering each other enormous blocks of securities at a third of their old prices" and "finding no one strong enough to pick up the sure fortunes they were compelled to offer." (20)

Winston Churchill and Stanley Baldwin

While he was away in the United States the Conservative Shadow Cabinet agreed with Stanley Baldwin that they would support the Labour Government's plans for India. The decision, announced by the Viceroy of India, was to grant Dominion Status to India. While retaining a Viceroy appointed from London, and British military control of defence, the country would be ruled within a few years by Indians at both the national and provincial levels. Churchill was certain this was a wrong decision and that the people of India were not ready to govern themselves. He wrote an article in The Daily Mail defending British rule of India: "Justice has been given - equal between race and race, impartial between man and man. Science, healing or creative, has been harnessed to the service of this immense and, by themselves, helpless population." (21)

Churchill now concentrated on writing his first volume of his autobiography. Entitled, My Early Life (1930), it covered his career from birth to his separation from the Conservative Party in 1903. It has been argued by Roy Jenkins, the author of Churchill (2001): "Many consider this to be Churchill's best book, and some would put it as one of the most outstanding works of the twentieth century... What most distinguished the book was that it was designed not to prove a point or to advance a theory but to entertain. In consequence there disappeared the somewhat portentous and tendentiously partial citation of documents, which, even though interspersed by pages of sparkling description and polemic, somewhat marred both The World Crisis and The Second World War. They were replaced by a most agreeable mockery of himself and of others with whom he came into contact." (22)

Winston Churchill's handling of the economy was blamed for the Conservative government's defeat in 1929. Churchill's opposition to the party's policy on India also upset Stanley Baldwin, the leader of the party, who was attempting to make the Conservatives a centre party. In 1931 when Baldwin, joined the National Government, he refused to allow Churchill to join the team because his views were considered to be too extreme. This included his idea that "democracy is totally unsuited to India" because they were "humble primitives". When the Viceroy of India, Edward Wood, told him that his opinions were out of date and that he ought to meet some Indians in order to understand their views, he rejected the suggestion: "I am quite satisfied with my views of India. I don't want them disturbed by any bloody Indian." (23)

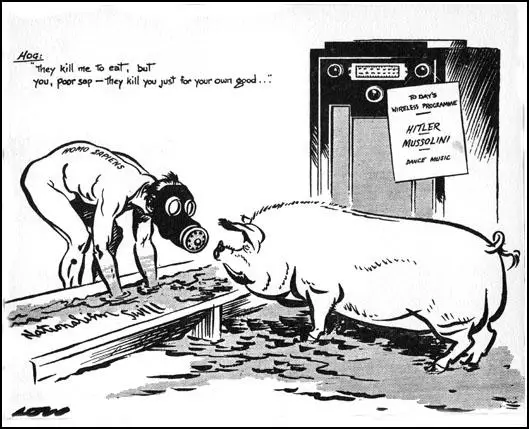

Churchill also questioned the idea of democracy and asked "whether institutions based on adult suffrage could possibly arrive at the right decision upon the intricate propositions of modern business and finance". He then suggested a semi-corporatist, anti-democratic alternative that would have been similar to the authoritarian state imposed on Italy by Benito Mussolini and Germany by Adolf Hitler. Churchill had been an early supporter of Mussolini: "Fascismo's triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism... proved the necessary antidote to the Communist poison." (24)

In an article published in the Evening Standard in January, 1934, he declared that with the advent of universal suffrage the political and social class to which he belonged was losing its control over affairs and "a universal suffrage electorate with a majority of women voters" would be unable to preserve the British form of government. His solution was to go back to the nineteenth-century system of plural voting - those he deemed suitable would be given extra votes in order to outweigh the influence of women and the working class and produce the answer he wanted at General Elections. (25)

On 7th June 1935, Ramsay MacDonald went to see George V to tell him he was resigning as head of the National Government. Henry Channon, the Conservative MP for Southend, commented in his diary: "I am glad Ramsay (MacDonald) has gone: I have always disliked his shifty face, and his inability to give a direct answer. What a career, a life-long Socialist, then for 4 years a Conservative Prime Minister, and now the defender of Londonderry House. An incredible volte-face. He ends up distrusted by Conservatives and hated by Socialists." (26)

Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister for the third time. Parliament was dissolved on 25th October 1935 and the General Election was set for 14th November. On 31st October, Baldwin declared "I give you my word there will be no great armaments." Churchill disagreed with Baldwin and he responded by publishing an article in The Daily Mail where he stressed the need to build up Britain's armed forces: "I do not feel that people realise at all how near and how grave are the dangers of a world explosion." (27)

In the 1935 General Election the Conservative-dominated National Government lost 90 seats from its massive majority of 1931, but still retained an overwhelming majority of 255 in the House of Commons. Churchill held his seat with an increased majority. He fully expected to be invited to join the government but Baldwin ignored his claims. Churchill later wrote: "This was to me a pang and, in a way, an insult. There was much mockery in the press. I do not pretend that, thirsting to get on the move." (28)

The Rise of Fascism

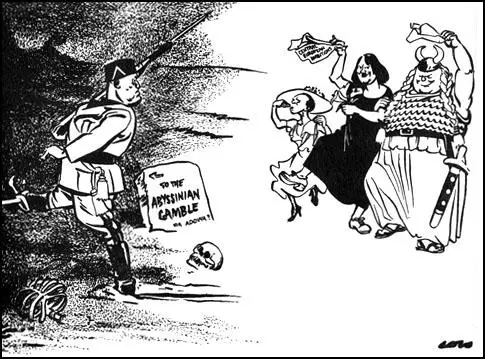

Winston Churchill gave support to Benito Mussolini in his foreign adventures. On 3rd October 1935, Mussolini sent 400,000 soldiers to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Haile Selassie, the ruler of appealed to the League of Nations for help, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure. As might have been expected, given his views of black people, Churchill had little sympathy for one of the two last surviving independent African countries. He told the House of Commons: "No one can keep up the pretence that Abyssinia is a fit, worthy and equal member of a league of civilised nations." (29)

As the majority of the Ethiopian population lived in rural towns, Italy faced continued resistance. Haile Selassie fled into exile and went to live in England. Mussolini was able to proclaim the Empire of Ethiopia and the assumption of the imperial title by the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III. The League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions in November 1935, but the sanctions were largely ineffective since they did not ban the sale of oil to Italy or close the Suez Canal, something that was under the control of the British. Despite the illegal methods employed by Mussolini, Churchill remained a loyal supporter. He told the Anti-Socialist Union that Mussolini was "the greatest lawgiver among living men". (30) He also wrote in The Sunday Chronicle that Mussolini was "a really great man". (31)

Sir Samuel Hoare, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, joined with Pierre Laval, the prime minister of France, in an effort to resolve the crisis created by the Italian invasion of Abyssinia. The secret agreement, known as the Hoare-Laval Pact, proposed that Italy would receive two-thirds of the territory it conquered as well as permission to enlarge existing colonies in East Africa. In return, Abyssinia, was to receive a narrow strip of territory and access to the sea. This was "the policy that Churchill had favoured all along". (32)

Details of the Hoare-Laval plan was leaked to the press on 10th December, 1935. Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, moved a vote of censure. He accused Stanley Baldwin of winning the 1935 General Election on one policy and pursuing another. "There is the question of the honour of this country, and there is the honour of the Prime Minister... If you turn and run away from the aggressor, you kill the League, and you do worse than that... you kill all faith in the word of honour of this country." (33)

Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Conservative MP, condemned the Pact and said: "Gentlemen do not behave in such a way". The Conservative Chief Whip told Baldwin: "Our men won't stand for it". The Government withdrew the plan, and Hoare was forced to resign. Churchill decided to keep out of the debate in case it put him in a bad light. Attlee wrote to his brother: "I fear that we are in for a bad time. The Government has no policy and no convictions. I have never seen a collection of ministers more hopeless after so short a time since an election." (34)

Adolf Hitler knew that both France and Britain were militarily stronger than Germany. However, their failure to take action against Italy, convinced him that they were unwilling to go to war. He therefore decided to break another aspect of the Treaty of Versailles by sending German troops into the Rhineland. The German generals were very much against the plan, claiming that the French Army would win a victory in the military conflict that was bound to follow this action. Hitler ignored their advice and on 1st March, 1936, three German battalions marched into the Rhineland. Hitler later admitted: "The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance." (35)

The British government accepted Hitler's Rhineland coup. Sir Anthony Eden, the new foreign secretary, informed the French that the British government was not prepared to support military action. The chiefs of staff felt Britain was in no position to go to war with Germany over the issue. The Rhineland invasion was not seen by the British government as an act of unprovoked aggression but as the righting of an injustice left behind by the Treaty of Versailles. Eden apparently said that "Hitler was only going into his own back garden." (36)

Winston Churchill agreed with the government position. In an article in the Evening Standard he praised the French for their restraint: "instead of retaliating with arms, as the previous generation would have, France has taken the correct course by appealing to the League of Nations". (37) In a speech in the House of Commons he supported the government's policy on appeasement and called on the League of Nations to invite Germany to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations" so that under the League's auspices "justice may be done and peace preserved". (38)

Clement Attlee attacked Churchill, Baldwin and Eden and the Conservative government for the acceptance that Hitler was allowed to march into the Rhineland without any measures taken against Germany. He spoke of the dangers of accepting Hitler's actions as merely righting one of the punitive wrongs of Versailles. "In the last five years we have had quite enough of dodging difficulties, of using forms of words to avoid facing up to realities... I am afraid that you may get a patched-up peace and then another crisis next year." (39)

Churchill supported General Francisco Franco and his Nationalist forces during the Spanish Civil War. He described the democratically elected Republican government as "a poverty stricken and backward proletariat demanding the overthrow of Church, State and property and the inauguration of a Communist regime." Against them stood the "patriotic, religious and bourgeois forces, under the leadership of the army, and sustained by the countryside in many provinces... marching to re-establish order by setting up a military dictatorship." (40)

As Geoffrey Best, the author of Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) has pointed out: "He (Churchill) was relatively unconcerned about what else went on in Europe. Eschewing the liberal-cum-socialist practice of bracketing together the two fascist dictators, he clung for long to a hope that Mussolini (whose regime in any case he correctly assessed as much less unpleasant than Hitler's) could be kept friendly or neutral in the forthcoming conflict. He was an anti-Nazi, not an anti-Fascist until very late in the day. He failed to give serious thought to the issues at stake in the Spanish Civil War and he did his own anti-Hitler campaign no good by appearing at that time to be pro-Franco." (41)

As C. P. Snow pointed out: "He (Churchill) lived until he was over ninety. If he had died at sixty-five, he would have been one of the picturesque failures in English politics - a failure like his own father, Lord Randolph Churchill, or Charles James Fox... His life, right up to the time when most men have finished, had been adventurous and twopence coloured, but he had achieved little. Except among his friends - and I mean his few real friends - he had never been popular. In most of his political life he had been widely and deeply disliked." (42)

Appeasement

During this period Churchill was a supporter of the government's appeasement policy. In April 1936 he called on the League of Nations to invite Germany "to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations" so that "justice may be done and peace preserved". (43) Churchill believed that the right strategy was to try and encourage Adolf Hitler to order the invasion of the Soviet Union. He wrote to Violet Bonham-Carter suggesting an alliance of Britain, France, Belgium and Holland to deter Germany from attacking in the west. He expected that Hitler would turn eastwards and attack the Soviet Union, and he proposed that Britain should stand aside while his old enemy Bolshevism was destroyed: "We should have to expect that the Germans would soon begin a war of conquest east and south and that at the same time Japan would attack Russia in the Far East. But Britain and France would maintain a heavily-armed neutrality." (44)

Stanley Baldwin's health so deteriorated that he announced that he would retire in May 1937. Neville Chamberlain was the obvious replacement. Churchill hoped that Chamberlain would offer him a post in his government. However, like Baldwin before him, Chamberlain was resolved to keep Churchill out of power. Blanche Dugdale reported that "It seems clear that Winston will not be invited to join Chamberlain's Cabinet. He (Chamberlain) quoted with approval a description of him made by Haldane when they were in Asquith's Cabinet: It is like arguing with a Brass band." (45)

As late as September, 1937, Churchill was praising Hitler's domestic achievements. In an article published in The Evening Standard after praising Germany's achievements in the First World War he wrote: "One may dislike Hitler’s system and yet admire his patriotic achievement. If our country were defeated I hope we should find a champion as indomitable to restore our courage and lead us back to our place among the nations. I have on more than one occasion made my appeal in public that the Führer of Germany should now become the Hitler of peace." (46)

Churchill went further the following month. "The story of that struggle (Hitler's rise to power), cannot be read without admiration for the courage, the perseverance, and the vital force which enabled him to challenge, defy, conciliate or overcome, all the authority or resistances which barred his path.". He then considered the way Hitler had suppressed the opposition and set up concentration camps: "Although no subsequent political action can condone wrong deeds, history is replete with examples of men who have risen to power by employing stern, grim and even frightful methods, but who nevertheless, when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives have enriched the story of mankind. So may it be with Hitler." (47)

In a speech at the Conservative Party conference on 7th October, 1937, he made it clear that he opposed the government's policy on India but supported its appeasement policy: "I used to come here year after year when we had some differences between ourselves about rearmament and also about a place called India. So I thought it would only be right that I should come here when we are all agreed... let us indeed support the foreign policy of our Government, which commands the trust, comprehension, and the comradeship of peace-loving and law-respecting nations in all parts of the world." (48)

On 12th March, 1938, the German Army invaded Austria. Churchill, like the Government and most of his fellow politicians, found it difficult to decide how to react to what seemed to be a highly popular peaceful union of the two countries. During the debate in the House of Commons, Churchill did not advocate the use of force to remove German forces from Austria. Instead he called for was discussion between diplomats at Geneva and still continued to support the government's appeasement policy. (49)

Winston Churchill now decided to become involved in discussions with representatives of Hitler's government in Nazi Germany. In July, 1938, Churchill had a meeting with Albert Forster, the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig. Forster asked Churchill whether German discriminatory legislation against the Jews would prevent an understanding with Britain. Churchill replied that he thought "it was a hindrance and an irritation, but probably not a complete obstacle to a working agreement." (50)

The Munich Agreement

In September 1938, Neville Chamberlain met Adolf Hitler at his home in Berchtesgaden. Hitler threatened to invade Czechoslovakia unless Britain supported Germany's plans to takeover the Sudetenland. After discussing the issue with the Edouard Daladier (France) and Eduard Benes (Czechoslovakia), Chamberlain informed Hitler that his proposals were unacceptable. Neville Henderson, the British ambassador in Germany, pleaded with Chamberlain to go on negotiating with Hitler. He believed, like Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, that the German claim to the Sudetenland in 1938 was a moral one, and he always reverted in his dispatches to his conviction that the Treaty of Versailles had been unfair to Germany. "At the same time, he was unsympathetic to feelers from the German opposition to Hitler seeking to enlist British support. Henderson thought, not unreasonably, that it was not the job of the British government to subvert the German government, and this view was shared by Chamberlain and Halifax". (51)

Benito Mussolini suggested to Hitler that one way of solving this issue was to hold a four-power conference of Germany, Britain, France and Italy. This would exclude both Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, and therefore increasing the possibility of reaching an agreement and undermine the solidarity that was developing against Germany. The meeting took place in Munich on 29th September, 1938. Desperate to avoid war, and anxious to avoid an alliance with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, Chamberlain and Daladier agreed that Germany could have the Sudetenland. In return, Hitler promised not to make any further territorial demands in Europe. (52)

The meeting ended with Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini signing the Munich Agreement which transferred the Sudetenland to Germany. "We, the German Führer and Chancellor and the British Prime Minister, have had a further meeting today and are agreed in recognizing that the question of Anglo-German relations is of the first importance for the two countries and for Europe. We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as Symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again. We are resolved that the method of consultation shall be the method adopted to deal with any other questions that may concern our two countries." (53)

Neville Henderson, the British ambassador in Berlin, defended the agreement: "Germany thus incorporated the Sudeten lands in the Reich without bloodshed and without firing a shot. But she had not got all that Hitler wanted and which she would have got if the arbitrament had been left to war... The humiliation of the Czechs was a tragedy, but it was solely thanks to Mr. Chamberlain's courage and pertinacity that a futile and senseless war was averted." (54)

On 3rd October, 1938, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, attacked the Munich Agreement in a speech in the House of Commons. "We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen today a gallant, civilised and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilisation and humanity, receive a terrible defeat.... The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence." (55)

Winston Churchill now decided to break with the government over its appeasement policy and two days after Attlee's speech made his move. Churchill praised Chamberlain for his efforts: "If I do not begin this afternoon by paying the usual, and indeed almost invariable, tributes to the Prime Minister for his handling of this crisis, it is certainly not from any lack of personal regard. We have always, over a great many years, had very pleasant relations, and I have deeply understood from personal experiences of my own in a similar crisis the stress and strain he has had to bear; but I am sure it is much better to say exactly what we think about public affairs, and this is certainly not the time when it is worth anyone’s while to court political popularity."

Churchill went on to say the negotiations had been a failure: "No one has been a more resolute and uncompromising struggler for peace than the Prime Minister. Everyone knows that. Never has there been such instance and undaunted determination to maintain and secure peace. That is quite true. Nevertheless, I am not quite clear why there was so much danger of Great Britain or France being involved in a war with Germany at this juncture if, in fact, they were ready all along to sacrifice Czechoslovakia. The terms which the Prime Minister brought back with him could easily have been agreed, I believe, through the ordinary diplomatic channels at any time during the summer. And I will say this, that I believe the Czechs, left to themselves and told they were going to get no help from the Western Powers, would have been able to make better terms than they have got after all this tremendous perturbation; they could hardly have had worse."

It was now time to change course and form an alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. "After the seizure of Austria in March we faced this problem in our debates. I ventured to appeal to the Government to go a little further than the Prime Minister went, and to give a pledge that in conjunction with France and other Powers they would guarantee the security of Czechoslovakia while the Sudeten-Deutsch question was being examined either by a League of Nations Commission or some other impartial body, and I still believe that if that course had been followed events would not have fallen into this disastrous state. France and Great Britain together, especially if they had maintained a close contact with Russia, which certainly was not done, would have been able in those days in the summer, when they had the prestige, to influence many of the smaller states of Europe; and I believe they could have determined the attitude of Poland. Such a combination, prepared at a time when the German dictator was not deeply and irrevocably committed to his new adventure, would, I believe, have given strength to all those forces in Germany which resisted this departure, this new design." (56)

Primary Sources

(1) Thomas Jones, diary entry (30th May, 1929)

At one desk sat Winston... sipping whisky and soda, getting redder and redder, rising and going out to glare at the tape machine himself, hunching his shoulders, bowing his head like a bull about to charge. As Labour gain after Labour gain was announced, Winston became more and more flushed with anger, left his seat and contronted the machine in the passage; with his shoulders hunched he glared at the figures, tore the sheets and behaved as though if any more Labour gains came along he would smash the whole apparatus. His ejaculations to the surrounding staff were quite unprintable.

References

(1) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 314

(2) Winston Churchill, letter to Clementine Churchill (6th January, 1927)

(3) Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (1991) page 480

(4) Winston Churchill, My Early Life (1930) page 373

(5) Winston Churchill, letter to Randolph Churchill (8th January, 1931)

(6) The Daily Mail (28th April, 1928)

(7) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 314

(8) Millicent Fawcett, diary entry (2nd July 1928)

(9) Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, letter to Leo Amery (12th November, 1928)

(10) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) pages 325-326

(11) Stuart Ball, Stanley Baldwin : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(12) The Conservative Manifesto: Mr. Stanley Baldwin's Election Address (May, 1929)

(13) The Labour Manifesto: Labour's Appeal to the Nation (May, 1929)

(14) Winston Churchill, speech at the Queen's Hall (12th February, 1929)

(15) Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (1991) page 489

(16) Thomas Jones, diary entry (30th May, 1929)

(17) Roy Hattersley, David Lloyd George (2010) page 608

(18) Winston Churchill, letter to David Lloyd George (28th July, 1929)

(19) Winston Churchill, letter to Clementine Churchill (27th August, 1929)

(20) Winston Churchill, diary entry (30th October, 1929)

(21) The Daily Mail (16th November, 1929)

(22) Roy Jenkins, Churchill (2001) page 420

(23) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 338

(24) The New York Times (21st January, 1927)

(25) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (24th January, 1934)

(26) Henry Channon, diary entry (June, 1935)

(27) Winston Churchill, The Daily Mail (12th November, 1935)

(28) Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (1991) page 547

(29) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (24th October 1935)

(30) Winston Churchill, speech (17th February, 1933)

(31) Winston Churchill, The Sunday Chronicle (26th May, 1935)

(32) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 376

(33) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (19th December, 1935)

(34) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 131

(35) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 345

(36) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 27

(37) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (13th March, 1936)

(38) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (6th April, 1936)

(39) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (26th March, 1936)

(40) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (10th August, 1936)

(41) Geoffrey Best, Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) page 155

(42) C. P. Snow, Variety of Men (1967) page 127

(43) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (6th April, 1936)

(44) Winston Churchill, letter to Violet Bonham-Carter (25th May 1936)

(45) Blanche Dugdale, diary entry (27th February, 1937)

(46) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (17th September 1937)

(47) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (14th October, 1937)

(48) Winston Churchill, speech at the Conservative Party conference at Scarborough (14th October, 1937)

(49) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (12th March, 1938)

(50) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 394

(51) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(52) Graham Darby, Hitler, Appeasement and the Road to War (1999) page 56

(53) Statement issued by Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler after the signing of the Munich Agreement (30th September, 1938)

(54) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 167

(55) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (3rd October, 1938)

(56) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (5th October, 1938)

John Simkin