On this day on 20th February

On this day the Bill of Rights Society was formed. In 1762, George III, arranged for his close friend, the Earl of Bute, to become Prime Minister. This decision upset a large number of MPs who considered Bute to be incompetent. John Wilkes, the MP for Aylesbury became Bute's leading critic in the House of Commons. In June 1762 Wilkes established The New Briton, a newspaper that severely attacked the king and his Prime Minister.

After one article that appeared on 23rd April 1763, George III and his ministers decided to prosecute John Wilkes for seditious libel. He was arrested but at a court hearing the Lord Chief Justice ruled that as an MP, Wilkes was protected by privilege from arrest on a charge of libel. However, on 23rd November, 1763, Parliament voted that a member's privilege from arrest did not extend to the writing and publishing of seditious libels. Wilkes escaped to France but in March 1768 he returned to England and stood and won as the Radical candidate for Middlesex.

On 8th June John Wilkes was found guilty of libel and sentenced to 22 months imprisonment and fined £1,000. Wilkes was also expelled from the House of Commons but in February, March and April, 1769, he was three times re-elected for Middlesex. On all three occasions the decision of the Middlesex electorate was overturned by Parliament. In May the House of Commons voted that Colonel Henry Luttrell, the defeated candidate at Middlesex, should be accepted as the MP.

On 20th February 1769, a lawyer, John Glynn, organised a meeting at the London Tavern to discuss the refusal of the House of Commons to accept the election of John Wilkes. Glynn subscribed £3,340 to form an organisation, the Bill of Rights Society, that would help support the campaign to reinstate Wilkes. Robert Morris, a Welsh barrister, was elected secretary, John Horne Tooke became treasurer. Other members of the group included John Sawbridge, the MP for Hythe, Sir Cecil Wray, MP for East Retford and Sir John Molesworth, MP for Cornwall.

Meetings of the Bill of Rights Society took place fortnightly at the London Tavern. At first the main objective of the society was to "maintain and defend the liberty of the subject, and to support the laws and constitution of the country." John Horne Tooke, who eventually became the most important figure in the Society, believed that the organisation should campaign for a radical programme of parliamentary reform. Tooke managed to do this but some members disagreed and it was this conflict that eventually brought the Bill of Rights Society to an end in 1771.

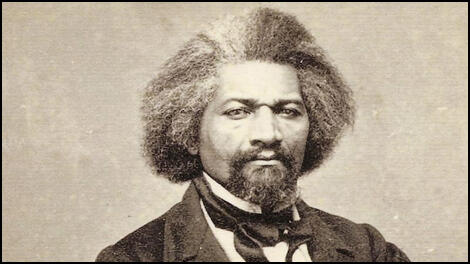

On this day in 1895 Frederick Douglass died. Frederick Washington Bailey, the son of a white man and a black slave, was born in Tukahoe, Maryland, on 7th February, 1817. He never knew his father and was separated from his mother when very young.

Douglas lived with his grandmother on a plantation until the age of eight, when he was sent to Hugh Auld in Baltimore. The wife of Auld defied state law by teaching him to read.

When Auld died in 1833 Frederick was returned to his Maryland plantation. In 1838 he escaped to New York City where he changed his name to Frederick Douglass. He later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a labourer.

After hearing him make a speech at a meeting in 1841, William Lloyd Garrison arranged for Douglass to become an agent and lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass was a great success in this work and in 1845 the society helped him publish his autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

After the publication of his book, Douglass was afraid he might be recaptured by his former owner and so he travelled to Britain where he lectured on slavery. While in Britain he raised the funds needed to establish his own anti-slavery newspaper, the North Star. This created a break with William Lloyd Garrison, who was opposed to a separate, black-owned press.

During the Civil War Douglass, a Radical Republican, tried to persuade President Abraham Lincoln that former slaves should be allowed to join the Union Army. After the war Douglass campaigned for full civil rights for former slaves and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

Douglass held several public posts including assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), marshall of the District of Columbia (1877-1881) and U.S. minister to Haiti (1889-1891). In 1881 he published the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

On this day in 1902 Ansel Adams was born in San Francisco. His original ambition was to become a concert pianist, but this changed after a trip to Yosemite National Park in 1916 when he took his first photographs.

Adams worked as a photo technician and as a caretaker at the Sierra Club in Yosemite Valley before he was able to become a full-time photographer. His first two collections of landscape photographs, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras (1927) and Taos Pueblo (1930), were published in limited editions. His first one-man show was held in San Francisco in 1932. This was followed by another in New York in 1936.

Greatly influenced by the work of Paul Strand, Adams was one of the founders with Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham of the Group f/64. Members of the group tended to use large cameras and small apertures to capture a wider range of different textures.

Throughout his early career, Adams combined commercial assignments and his own work. This included Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail (1938); Illustrated guide to Yosemite Valley (1940); a book about the plight of interned Japanese-Americans, Born Free and Equal (1944), Yosemite and the High Sierra (1948) and My Camera in Yosemite Valley (1949). In all, Adams published twenty-four photographic books on the National Parks of America. As one critic has argued: "Adams created a body of work which has come to exemplify not only the purist approach to the medium, but to many people the definitive pictorial statement on the American western landscape."

In 1940 Adams also helped to set up the department of photography at the New York Museum of Modern Art. Four years later he established the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, the first academic department to teach photography as a profession. He was for a time also a member of the Photo League.

In 1953 Adams collaborated with Dorothea Lange on a photo essay on the Mormons in Utah for Life Magazine. He also established a photography workshop in Yosemite.

Ansel Adams died in Carmel, California on 22nd April, in 1984.

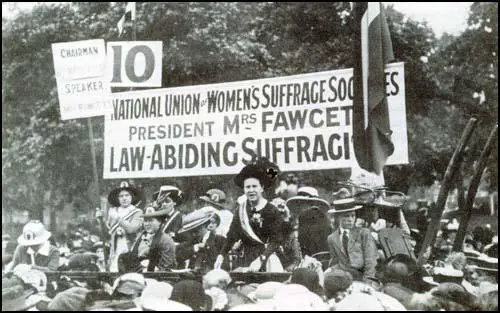

On this day in 1914 the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies finally gives up hope in persuading Herbert Asquith's Liberal government to give women the vote and forms an electoral alliance with the Labour Party.

culmination of the Pilgrimage on 26th July 1913.

On this day in 1920 Washakie died. He was buried with full military honours at Fort Washakie, Wyoming. Washakie was born in 1804. His father was a Flathead but his mother was a member of the Shoshone tribe. He developed a reputation as a fierce warrior against rival tribes such as the Sioux and Blackfeet. However he developed a policy of friendship with white settlers and the American government. He was hired by both the Hudson's Bay Company and American Fur Company and worked as a guide for white trappers.

Washakie eventually became chief of the Shoshone. His record of friendship towards the authorities allowed him to negotiate good treaties for his people. In 1868 he obtained the White River Valley Reservation in Wyoming, and area still rich in buffalo.

In 1876 Washakie supplied scouts and warriors to help the United States army to defeat the Sioux . President Ulysses Grant was so pleased with Washakie's contribution to the Indian Wars that he presented him with an expensive saddle.

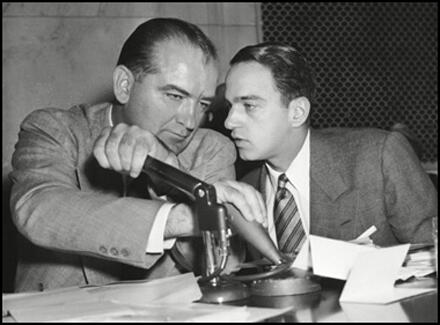

On this day in 1927 Roy Cohn was born in New York City. His father, Albert Cohn, was a New York State judge and an important figure in the Democratic Party.

After being educated at the best private school in Manhattan, he entered Columbia Law School. Admitted to the bar at twenty-one, he used his connections to become a Assistant U.S. Attorney in Manhattan. He played a prominent role in the trial of eleven leaders of the American Communist Party and in the prosecution of Julius Rosenberg and Ethel Rosenberg in 1951.

In 1952 Joseph McCarthy appointed Roy Cohn as the chief counsel to the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. Cohn had been recommended by Edgar Hoover, who had been impressed by his involvement in the prosecution of the Rosenburgs. Soon after Cohn was appointed, he recruited his best friend, David Schine, to become his chief consultant.

For some time opponents of McCarthy had been accumulating evidence concerning his homosexual relationships. Rumours began to circulate that Cohn and David Schine were having a sexual relationship. Although well-known by political journalists, it did not become public until Hank Greenspun published an article in the Las Vegas Sun in 25th October, 1952.

Joseph McCarthy considered a libel suit against Greenspun but decided against it when he was told by his lawyers that if the case went ahead he would have to take the witness stand and answer questions about his sexuality. In an attempt to stop the rumours circulating, McCarthy married his secretary, Jeannie Kerr. Later the couple adopted a five-week old girl from the New York Foundling Home.

In October, 1953, McCarthy began investigating communist infiltration into the military. Attempts were made by McCarthy to discredit Robert Stevens, the Secretary of the Army. The president, Dwight Eisenhower, was furious and now realised that it was time to bring an end to McCarthy's activities.

The United States Army retaliated by passing information about Joseph McCarthy to journalists known to be opposed to him. This included the news that Cohn had abused congressional privilege by trying to prevent David Schine from being drafted. When that failed, it was claimed that Cohn tried to pressurize the Army to grant Schine special privileges. The well-known newspaper columnist, Drew Pearson, published the story on 15th December, 1953.

The televised hearings of the Senate hearings exposed the tactics of Cohn and Joseph McCarthy. Leading politicians in both parties, had been embarrassed by McCarthy's performance and on 2nd December, 1954, a censure motion condemned his conduct by 67 votes to 22. Cohn was forced to resign but he managed to join a New York law firm and over the years represented an impressive list of high-profile clients.

Cohn developed a reputation for high living. He made a great deal of money from his activities but his expensive tastes resulted in him owing three million dollars in unpaid taxes. Cohn was a survivor and in 1979 admitted that: "My idea of real power is not people who hold office. They're here today and gone tomorrow. Power means the ability to get things done. It stems from friendship in my case."

In the 1980s Cohn's luck ran out. Disbarred from practicing law in New York State on grounds of unethical and unprofessional conduct, he contacted AIDs. Roy Cohn died on 2nd August, 1986.

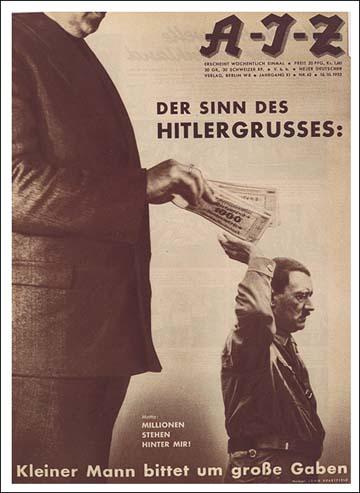

On this day in 1933 Adolf Hitler secretly met with German industralists to arrange the financing of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) in the upcoming election. Hermann Goering told them that the 1933 General Election could be the last in Germany for a very long time. Goering added that the NSDAP would need a considerable amount of of money to ensure victory. Those present responded by donating 3 million Reichmarks. As Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary after the meeting: "Radio and press are at our disposal. Even money is not lacking this time."

(Copyright The Official John Heartfield Exhibition & Archive)

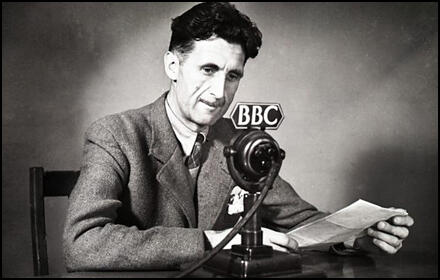

On this day in 1943 George Orwell gave a BBC radio broadcast on the Beveridge Report. "The Beveridge scheme of social security is still under debate. The government has already proposed the adoption of the greater part of it but a Labour amendment in the House of Commons demanding the adoption of the scheme in its entirety received as many as 117 votes have spoken of the Beveridge scheme in earlier news commentaries and don't want to detail its provisions again I merely mention the debate now taking place in order to emphasize two things. One is, that whatever else goes through, family allowances are certain to be adopted though it is not yet certain on what scale. The other is that the principle of social insurance has come to stay and even the most reactionary thinkers in Great Britain would now hardly dare to oppose this. The Beveridge scheme may ultimately be adopted in the somewhat mutilated form, but it is something of an achievement even to be debating such a thing in the middle of a desperate war in which we are still fighting for survival."

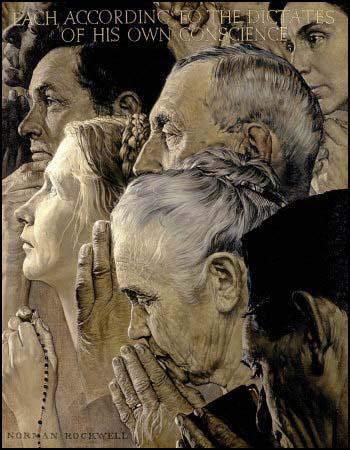

On this day in 1943 the Saturday Evening Post published the first of Norman Rockwell's Four Freedoms. Rockwell was inspired by a joint statement made by Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill about the reasons why it was important to fight a war against Nazi Germany. In his autobiography, he points out that after returning from a town meeting: "My gosh, I thought, that's it. There it is. Freedom of Speech. I'll illustrate the Four Freedoms using my Vermont neighbors as models. I'll express the ideas in simple, everyday scenes. Freedom of Speech - a New England town meeting. Freedom from Want - a Thanksgiving dinner."

The Freedom of Speech painting showed Jim Edgerton, who had argued for the building of a new high school in Arlington. Edgerton had found no support for his views. But the meeting had listened respectfully to his views. Norman Rockwell considered this was a good example of freedom of speech in action.

Rockwell found coming up with an idea for a painting on religion much more difficult. After making several false starts he painted a close-up portrait of seven individuals of various skin tones, united in prayer. Freedom to Worship included the words in golden letters at the top of the canvas: "Each according to the dictates of his own conscience."

Freedom from Want depicted his own family. The Rockwell cook, Mrs. Wheaton, is shown presenting the turkey. His wife, Mary Rockwell, can be seen on the left side of the table. His mother is the elderly lady seated across from her. Rockwell later recalled: "She (Mrs. Wheaton) cooked it, I painted it, and we ate it. That was one of the few times I've ever eaten the model."

The final painting, Freedom from Fear, was produced during the Blitz. It shows the husband and wife watching their two children asleep. The man carries a newspaper, with a headline referring to the bombing of London. His biographer, Karal Ann Marling, argues that: "The rag doll abandoned on the floor just behind his feet echoes the posture of the sleeping children but, in her limp, discarded form, also alludes to the European children who did not enjoy the safety of a warm bed guarded by caring parents."

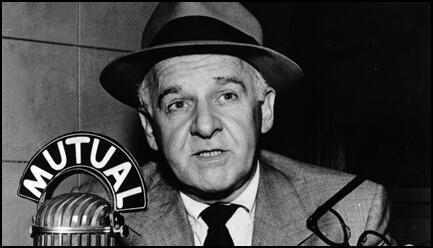

On this day in 1972 Walter Winchell died of prostate cancer. Winchell was born in New York City on 7th April 7, 1897. After leaving school he worked for a vaudeville troupe. It soon became clear that he was not going to be a success in this profession and in 1920 he found work as a journalist for Vaudeville News. Four years later he joined the Evening Graphic .

Winchell's career did not take off until he was recruited by the New York Daily Mirror in 1929, a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst. Winchell started a gossip column, entitled On-Broadway. Winchell used his connections to publish confidential information about people in the public eye. His work appeared in nearly 2,000 newspapers and he also did a Sunday radio broadcasts. Combined, they reached 50 million homes. His attorney, Ernest Cuneo, has argued that "when Walter finished broadcasting on Sunday night, he had reached 89 out of 100 adults in the U.S." Bernard Weinraub has pointed out: "From Table 50 at the Stork Club - he never picked up the tab - Winchell held court like a prince, beckoning prizefighters, movie stars, debutantes, royalty and gangsters to his table. He demanded to know what they were doing but talked most of the time himself." Jennet Conant has argued that "Winchell was a powerhouse widely feared because of his penchant for exposing the private lives of important public men - from mistresses and pregnancies to divorces - which gave him plenty of bargaining chips to trade for information about what was going on inside their businesses or agencies."

Ralph D. Gardner, a fellow journalist, has argued: "Feeding the public’s craving for scandal and gossip, he became the most powerful - and feared - journalist of his time.... The columns, written in his own style, were composed of short sentences connected by three dots. Fed by press agents, tipsters, legmen and ghost writers, he possessed the extraordinary ability to make a Broadway show a hit, create overnight celebrities; enhance or destroy a political career. The workaholic Winchell was first to announce big-name marriages and divorces, Hollywood romances, exploits of socialites, international playboys, debutantes, mobsters and chorus girls, plus latest reports of café society antics... He would also give timely plugs to show-biz unknowns or has-beens who were sorely in need of a helping hand. At the same time he savaged any whom he perceived to be his enemies." Winchell was a powerhouse widely feared because of his penchant for exposing the private lives of important public men - from mistresses and pregnancies to divorces - which gave him plenty of bargaining chips to trade for information about what was going on inside their businesses or agencies. The New York Times described Winchell as "the country’s best-known, widely read journalist as well as its most influential."

Winchell, who was Jewish, was one of the first journalists to condemn Adolf Hitler and isolationist groups such as the American First Committee. Winchell argued that "isolation ends where it always ends - with the enemy on our doorstep", and introduced a regular feature called "The Winchell Column vs. the Fifth Column." Later, Ernest Cuneo, who was working with the British Security Coordination (BSC), claimed: "FDR was at war with Hitler long before Chamberlain was forced to declare it. I was eyewitness and indeed, wrote Winchell's stuff on it."

Winchell was a staunch supporter of President Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal throughout the 1930s. He also held strong views on civil rights and frequently attacked the Ku Klux Klan. The author of The Irregulars: Roald Dahl and the British Spy Ring in Wartime Washington (2008) has argued: "He had morphed from a Broadway critic to a political commentator who thought nothing of weighing in on domestic and international affairs... A typical Winchell column would contain several dozen separate references to individuals and events, ranging from minor celebrity sightings, along the lines of spotting Marlene Diettrich at the Stork Club, his nightly hangout, to an impassioned denunciation of Nazi sympathizers or some other disreputable homegrown fascists."

Benjamin de Forest Bayly has suggested that William Stephenson, who was head of BSC, was very close to Winchell: "He liked propaganda. And propaganda was really one of the important things he did. He saw to it, before even Pearl Harbor, that the anti-British feeling there was squelched by writers. He got all sorts of people to write things that helped that... Winchell was a man who actually got a reputation for being a very straightforward person, and he did a lot of propaganda work for Bill Stephenson. If Bill could sell him on why the U.S. should do this, and if it did that, then Winchell would be your man."

Winchell became a close friend of J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI, in 1938. Curt Gentry, the author of J. Edgar Hoover: The Man and the Secrets (1991): "Unquestionably each used the other. It was Winchell, more than any other journalist, who sold the G-man image to America; while Hoover, according to Cuneo and others, supplied Winchell with inside information that led to some of his biggest scoops.... In addition to the tips, Hoover often supplied Winchell with an FBI driver when he was travelling; assigned FBI agents as bodyguards whenever the columnist received a death threat, which was often."

In early August 1939 Winchell received a message from a contact that suggested that Louis Lepke Buchalter was willing to surrender to the FBI if a deal was possible. Lepke was unwilling to surrender to New York's district attorney, Thomas Dewey, as he had vowed to execute him. Winchell now made a radio broadcast appealing to Lepke to give himself up: "Attention Public Enemy Number One, Louis 'Lepke' Buchalter! I am authorized by John Edgar Hoover of the Federal Bureau of Investigation to guarantee you safe delivery to the FBI if you surrender to me or to any agent of the FBI. I will repeat: Leapke, I am authorized by John Edgar Hoover."

On 24th August Winchell received another message from Lepke. He phoned J. Edgar Hoover: "My friends, John, have instructed me to tell you to be at Twenty-eighth Street and Fifth Avenue between ten-ten and ten-twenty tonight. That's about half an hour. They told me to tell you to be alone." Curt Gentry explains that "Hoover was not on foot, and he wasn't alone. Unknown to Winchell, more than two dozen agents had the corner under surveillance. Having picked up Lepke several blocks away, per instructions, Winchell pulled up beside the director's distinctive black limousine. Then he and Lepke got into the back of the FBI vehicle." Winchell later recalled that Hoover was "disguised in dark glasses to keep him from being recognized by passersby".

Louis Lepke Buchalter was tried on federal charges and sentenced to fourteen years in Leavenworth (Hoover had promised him he'd get only ten years and that with good behaviour he'd be out in five or six). The Chicago Tribune published a story that the FBI and the Justice Department had made a deal with Lepke, to keep him from telling what he knew about the Roosevelt administration's links with Murder Incorporated. President Franklin Roosevelt was so angry about the accusation he ordered that Lepke should be handed over to Thomas Dewey. When Abe Reles agreed to provide evidence against Buchalter, he was tried for murder. Found guilty, Buchalter was executed at Sing Sing State Prison on 4th March, 1944.

After the Second World War Winchell became obsessed with the threat of communism. When Josephine Baker complained about the racial-discriminatory policies of the Stork Club in New York City he retaliated by calling her a communist and began a campaign which prevented her from getting her visa to enter the US renewed. He was criticised by fellow journalists, including Ed Sullivan, who said, ''I despise Walter Winchell because he symbolizes to me evil and treacherous things in the American setup.''

Winchell also gave his support to Joseph McCarthy. As Ralph D. Gardner has pointed out: "In the 1950’s Winchell’s direction took an odd turn that was distressing to millions of readers. He became a supporter of Sen. Joseph McCarthy, filling his pages and broadcasts with vindictive, denunciatory tirades and mean-spirited accusations that resulted in lawsuits and loss of media outlets. He had climbed to the top and tumbled." In 1963 New York Daily Mirror, a newspaper who he worked for 34 years, closed, his life as a columnist came to an end.