On this day on 8th April

On this day in 1827 women's suffrage campaigner Barbara Leigh Smith, the daughter of Benjamin Leigh Smith and Anne Longden, was born near Robertsbridge, Sussex, in 1827. Her father came from a well-known unitarian radical family. Barbara's grandfather, had worked closely in Parliament with William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson in their campaign against the slave-trade and had supported the French Revolution, whereas her great-grandfather had favoured the American colonists against the British government. The family was also related to Fanny Smith, the mother of Florence Nightingale.

When Barbara was born her father was a member of the House of Commons and her mother, Anne Longden, was a seventeen-year old milliner who had been seduced by Smith. The birth created a scandal because the couple did not marry. Anne remained his common-law wife until she died of tuberculosis when Barbara was only seven years old.

As her biographer, Pam Hirsch, has pointed out: "After the death of Anne Longden from tuberculosis in 1834, despite advice from some sections of his family to have the children discreetly brought up abroad, their father brought them up himself, first at Pelham Crescent, Hastings, and later at his London home, 5 Blandford Square, Marylebone. As the Leigh-Smith children were illegitimate they were not acknowledged by many of their Smith relations, including their aunt Fanny Nightingale and their first cousin, Florence Nightingale"

The home of Benjamin Leigh-Smith was also a meeting place for fellow radicals and political refugees. This gave Barbara the opportunity to meet and make friends with a wide-range of different people involved in politics. Leigh Smith was an advocate of women's rights and treated Barbara the same way as her brothers. Barbara and her four brothers and sisters attended the local school where they were educated with working class children.

At the age of twenty-one, Benjamin Leigh-Smith gave all his children £300 a year. It was extremely unusual for fathers to treat their daughters this way and it gave Barbara the chance to be independent of her family. Barbara used some of this money to establish her own progressive school in London. Barbara selected Elizabeth Whitehead to be the school's headteacher. Before opening what later became known as the Portman Hall School, Barbara and Elizabeth made a special study of primary schools in London. It was decided to establish an experimental school that was undenominational, co-educational, and for children of different class backgrounds.

According to Ray Strachey, the author of The Cause: A History of the Women's Movement in Great Britain (1928) "Barbara Leigh-Smith... moved in legal, political, literary, and artistic circles from her early youth... Tall, handsome, generous and quite unselfconscious, she swept along, distracted only by the too great abundance of her interests and talents, and the too great outflowing of her sympathies."

Barbara Leigh-Smith took a keen interest in the legal rights of women. Ernest Sackville Turner has argued that the "Common Law of England, in the early part of the 19th century, granted a wife fewer rights than had been accorded to under the later Roman law, and hardly more than had been conceded to an African slave before emancipation... The husband... owned her body, her property, her savings, her personal jewels and her income, whether they lived together or separately." Turner goes on to point out, that the husband "could legally support his mistress on the earnings of his wife".

John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, was one of the few men who was willing to speak up for women: "She can acquire no property, but for the husband: the instant it becomes hers, even if by inheritance, it becomes ipso facto his... This is her legal state. And from this state she has no means to withdraw herself. If she leaves her husband she can take nothing with her, neither her children nor anything which is rightfully her own. If he chooses he can compel her to return by law, or by physical force; or he may content himself with seizing for his own use anything which she may earn or which may be given to her by her relations. It is only separation by a decree of a court of justice which entitles her to live apart without being forced back into the custody of an exasperated jailer."

In 1850 a Royal Commission had recommended that the government took a look into the workings of the Divorce Law. Robert Rolfe, 1st Baron Cranworth, took up the challenge and when he was appointed Lord Chancellor he began to draw up new legislation. Caroline Norton, who had been involved in the passing of the Custody of Children Act, contacted Cranworth and requested that he included a clause that would ensure that wives could retain their own property after marriage.

As part of her campaign Norton published the pamphlet, English Laws for Women in the Nineteenth Century (1854). She explained that after years of experiencing violence from her husband she was unable to obtain a divorce: "I consulted whether a divorce 'by reason of cruelty' might not be pleaded for me; and I laid before my lawyers the many instances of violence, injustice, and ill-usage, of which the trial was but the crowning example. I was then told that no divorce I could obtain would break my marriage; that I could not plead cruelty which I had forgiven; that by returning to Mr Norton I had 'condoned' all I complained of. I learnt, too, the law as to my children – that the right was with the father; that neither my innocence nor his guilt could alter it; that not even his giving them into the hands of a mistress, would give me any claim to their custody. The eldest was but six years old, the second four, the youngest two and a half, when we were parted. I wrote, therefore, and petitioned the father and husband in whose power I was, for leave to see them – for leave to keep them, till they were a little older. Mr Norton's answer was, that I should not have them; that if I wanted to see them, I might have an interview with them at the chambers of his attorney."

Norton also wrote a letter to Queen Victoria complaining about the position of women in regards to divorce. "If her husband take proceedings for a divorce, she is not, in the first instance, allowed to defend herself. She has no means of proving the falsehood of his allegations... If an English wife be guilty of infidelity, her husband can divorce her so as to marry again; but she cannot divorce the husband, however profligate he may be. No law court can divorce in England. A special Act of Parliament annulling the marriage, is passed for each case. The House of Lords grants this almost as a matter of course to the husband, but not to the wife. In only four instances (two of which were cases of incest), has the wife obtained a divorce to marry again."

Barbara Leigh-Smith joined the campaign, and published Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women (1854). It included the following passage: "A man and wife are one person in law; the wife loses all her rights as a single woman, and her existence is entirely absorbed in that of her husband. He is civilly responsible for her acts; she lives under his protection or cover, and her condition is called coverture. A woman's body belongs to her husband; she is in his custody, and he can enforce his right by a writ of habeas corpus."

In 1854 Barbara Leigh Smith became friends with Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies and Bessie Rayner Parkes. She introduced the women to the works of Mary Wollstonecraft. Davies later wrote that the women were the first people "who sympathised with my feelings of resentment at the subjection of women". According to Margaret Forster, the author of Significant Sisters (1984), Davies was especially impressed with Barbara: "Although she was not at all the sort of person who adored anyone... but quickly came to adore Barbara. She even approved of how she dressed, in loose flowing clothes with her long blonde hair flowing down her back. She was, in every sense, a revelation."

A group of women, including Barbara Leigh-Smith, Emily Davies, Elizabeth Garrett and Dorothea Beale, organised a petition demanding equal legal rights with men. The petition signed by 26,000 men and women was submitted to Parliament. It was accepted by John Stuart Mill in the House of Commons and Lord Henry Brougham in the House of Lords. "The subject was almost entirely new to public consideration, and, as was natural, the feeling both in support of and in opposition to change was very strong. It would disrupt society, people said; it would destroy the home, and turn women into loathsome, self-assertive creatures no one could live with."

The proposed Marriage and Divorce Act was discussed at great length in 1857. William Ewart Gladstone, the future leader of the Liberal Party, was a strong opponent of the bill as he saw it as undermining the authority of the Church. He made seventy-three interventions against the bill, twenty-nine of them in the course of one protracted sitting. However, he was in a small minority and could only gain the support of a "few dozen votes".

In the House of Lords, John Bird Sumner, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Henry Phillpotts, Bishop of Exeter, both supported the measure and became law in January, 1858. Its main purpose was to transfer jurisdiction on divorce from Parliament and the ecclesiastical courts to a new tribunal. This simplified proceedings and radically lowered divorce costs, thereby making it available to a larger section of the population. Actions for "criminal conversations" were abolished.

The new law did not treat men and women on a equal basis. A man could divorce a woman if she was "guilty of adultery". However, the woman could only obtain a divorce if she could show that "her husband has been guilty of incestuous adultery, or of bigamy with adultery, or of rape, or of sodomy or bestiality, or of adultery coupled with such cruelty as without adultery would have entitled her to a divorce, or of adultery coupled with desertion, without reasonable excuse, for two years or upwards."

Barbara Leigh-Smith was very critical of a legal system that failed to protect the property and earnings of married women. In 1857 Barbara wrote Women and Work where she argued that a married women's dependence on her husband was degrading. As a young woman Barbara had fallen in love with John Chapman, the editor of the Westminster Review. He proposed a "free-love" relationship with her, and she was deeply tempted despite his being already married.

In the winter of 1856, owing to the ill health of one of her sisters, Isabella, Benjamin Leigh Smith took his three daughters to Algiers. There Barbara met Eugène Bodichon, a French physician and ethnographer. Barbara fell in love with Bodichon, who was seventeen years her senior. Her father initially disapproved but he eventually relented and the couple were married on 2nd July 1857. They went on honeymoon to America so that they could get obtain information on the subject of slavery and during their visit they had a meeting with Lucretia Mott.

Her father's wedding gift was his house in Blandford Square. As a consequence of her marriage she spent half of each year in Algiers with her husband concentrating on her artistic career and half the year in England involved with social reform. In 1858 Barbara Bodichon and her friend, Bessie Rayner Parkes, founded the journal, The Englishwoman's Review. For the next few years the two women made their journal available to women campaigning for women doctors and the extension of opportunities for women in higher education.

In 1859 Barbara Bodichon bought a Moorish-style house on Mustapha Supérieure, overlooking the Bay of Algiers, which she named Campagne du Pavillon. It became a centre for English and French artistic and literary visitors to Algiers. As her husband hated London, in 1863 she built another house, Scalands Gate, in Robertsbridge. "Her husband was an eccentric man who neither learned English nor made much effort to endear himself to her family or friends. More positively, he accepted his wife's commitment to her career as an artist and her work as a social reformer."

Barbara Bodichon continued to campaign for women's rights and in 1865 she joined a group of women in London to form a discussion group called the Kensington Society. Other members included Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Francis Mary Buss, Dorothea Beale, Anne Clough, Sophia Jex-Blake, Frances Power Cobbe, Helen Taylor, Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy and Elizabeth Garrett. One of the members commented that "none but intellectual women are admitted and therefore it is not likely to become a merely puerile and gossiping Society."

On 21st November 1865, the women discussed the topic of parliamentary reform. The question was: "Is the extension of the Parliamentary suffrage to women desirable, and if so, under what conditions?. Barbara Bodichon submitted a paper on the topic. The women thought it was unfair that women were not allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. They therefore decided to draft a petition asking Parliament to grant women the vote. After obtaining 1,500 signatures, the women took their petition to Henry Fawcett a MP who supported universal suffrage.

In 1866 Lydia Becker heard Barbara Bodichon give a lecture on women's suffrage at a meeting in Manchester. She was immediately converted to the idea that women should have the vote and along with Elizabeth Wolstenholme-Elmy, Josephine Butler, Eva Maclaren, Esther Roper and Eva Gore-Booth, helped establish the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage.

In May 1866, Barbara Bodichon wrote to Helen Taylor about the need for votes for women. "I am very anxious to have some conversation with you about the possibility of doing something immediately toward giving women votes. I should like to start a petition or making any movement without knowing what you and Mr J.S. Mill thought expedient at this time. I have only just arrived in London from Algiers but I have already seen many ladies who are willing to take some steps for this cause."

Taylor replied:"I think that while a reform bill is under discussion and petitions are being presented to Parliament from various causes - asking for representation or protesting against disfranchisement, it is very desirable that women who wish for political enfranchisement should say so." With the help of Jessie Boucherett, Emily Davies, Bessie Rayner Parkes and Elizabeth Garrett, she managed to persuade 1,499 women to sign the petition.

On 20th May 1867, John Stuart Mill, the Radical MP for Westminster, and the leading male supporter in favour of women's suffrage, proposed that women should be granted the same rights as men in the proposed 1867 Reform Act. "We talk of political revolutions, but we do not sufficiently attend to the fact that there has taken place around us a silent domestic revolution: women and men are, for the first time in history, really each other's companions... when men and women are really companions, if women are frivolous men will be frivolous... the two sexes must rise or sink together."

During the debate on the issue, Edward Kent Karslake, the Conservative MP for Colchester, said in the debate that the main reason he opposed the measure was that he had not met one woman in Essex who agreed with women's suffrage. Lydia Becker, Helen Taylor and Frances Power Cobbe, decided to take up this challenge and devised the idea of collecting signatures in Colchester for a petition that Karslake could then present to parliament. They found 129 women resident in the town willing to sign the petition and on 25th July, 1867, Karslake presented the list to parliament. Despite this petition the Mill amendment was defeated by 196 votes to 73.

Barbara Bodichon fell out with other members of the Manchester National Society for Women's Suffrage over the issue of a women-only suffrage committee. Barbara disagreed with this strategy, believing that the loss of politically experienced men from their committee "might cost them ten years". As a consequence Barbara resigned from the suffrage committee in June 1867. However, her article, Reasons for and against the Enfranchisement of Women, was republished several times, in the propaganda campaign that followed.

Although her main efforts went into the women's suffrage campaign, Bodichon continued her work to improve women's education. She joined forces with her old friend, Emily Davies, to campaign to obtain a university college for women and provided an initial donation of £1,000. Eventually they raised enough money to purchase Benslow, a house two miles outside the town. In 1873 Benslow House was opened as Girton College.

The two women held different views on women's education. Emily Davies believed that the students should concentrate on traditional subjects such as classics and mathematics whereas Barbara Bodichon wanted a more radical approach to the curriculum. The two women also disagreed on student discipline. Davies favoured a strict regime compared to Barbara's more liberal approach. Students at Girton included Helena Swanwick, Eileen Power, Dora Russell, Margaret Llewelyn Davies, Margaret Cole and Dorothy Jewson.

In 1875, Hertha Ayrton, the daughter of a Jewish watchmaker, wrote to Barbara Bodichon about her desire to study mathematics at Girton College. With the financial help of Bodichon and Taylor she was able to attend Girton between 1877 and 1881. According to Pam Hirsch Hertha "virtually became a daughter to her".

When she was fifty-years of age, she was taken seriously ill and although she recovered she was left paralyzed. Although Bodichon retained her interest in women's rights, she was no longer able to take an active role in the movement. Bodichon remained an invalid until her death in Hastings on 11th June 1891. In her will Barbara Bodichon left a large sum of money to Girton College.

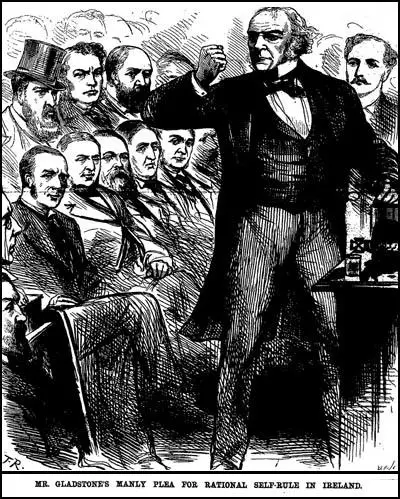

On this day in 1886 William Ewart Gladstone introduces the first Irish Home Rule Bill. Gladstone and the Liberals won the 1885 General Election, with a majority of seventy-two over the Tories. However, the Irish Nationalists could cause problems because they won 86 seats. On 8th April 1886, Gladstone announced his plan for Irish Home Rule. Mary Gladstone Drew wrote: "The air tingled with excitement and emotion, and when he began his speech we wondered to see that it was really the same familiar face - familiar voice. For 3 hours and a half he spoke - the most quiet earnest pleading, explaining, analysing, showing a mastery of detail and a grip and grasp such as has never been surpassed. Not a sound was heard, not a cough even, only cheers breaking out here and there - a tremendous feat at his age... I think really the scheme goes further than people thought."

The Home Rule Bill said that there should be a separate parliament for Ireland in Dublin and that there would be no Irish MPs in the House of Commons. The Irish Parliament would manage affairs inside Ireland, such as education, transport and agriculture. However, it would not be allowed to have a separate army or navy, nor would it be able to make separate treaties or trade agreements with foreign countries.

The Conservative Party opposed the measure. So did some members of the Liberal Party, led by Joseph Chamberlain, also disagreed with Gladstone's plan. Chamberlain main objection to Gladstone's Home Rule Bill was that as there would be no Irish MPs at Westminster, Britain and Ireland would drift apart. He added that this would be amounting to the start of the break-up of the British Empire. When a vote was taken, there were 313 MPs in favour, but 343 against. Of those voting against, 93 were Liberals. They became known as Liberal Unionists.

Gladstone responded to the vote by dissolving parliament rather than resign. During the 1886 General Election he had great difficultly leading a divided party. According to Colin Matthew: "So dedicated was Gladstone to the campaign that he agreed to break the habit of the previous forty years and cease his attempts to convert prostitutes, for fear, for the first time, of causing a scandal (Liberal agents had heard that the Unionists were monitoring Gladstone's nocturnal movements in London with a view to a press exposé)".

In the election the number of Liberal MPs fell from 333 in 1885 to 196, though no party gained an overall majority. Gladstone resigned on 30th July. Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, once again became prime minister. Queen Victoria wrote him a letter where she said she always thought that his Irish policy was bound to fail and "that a period of silence from him on this issue would now be most welcome, as well as his clear patriotic duty."

William Gladstone refused to retire and continued as leader of the opposition. He wrote several articles on the subject of Home Rule and questioned the idea that the House of Lords should be able to block government legislation. Although he remained active in politics, a decline in his hearing and eyesight made life difficult. "His memory, particularly for names but also for recent events, although not for more distant ones, showed signs of fading... On the other hand his physical stamina remained formidable. He felled his last tree a few weeks before his eighty-second birthday."

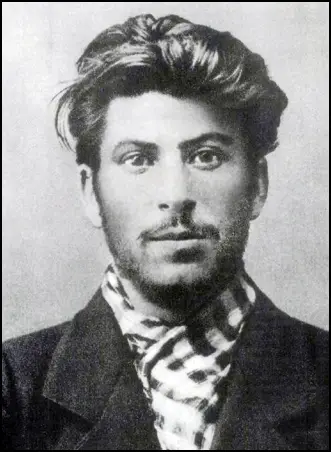

On this day in 1902 Joseph Stalin is arrested after coordinating a strike in Russia. The previous year Stalin joined the Social Democratic Labour Party and whereas most of the leaders were living in exile, he stayed in Russia where he helped to organize industrial resistance to Tsarism. On 18th April, 1902, Stalin was arrested after coordinating a strike at the large Rothschild plant at Batum and after spending 18 months in prison, Stalin was deported to Siberia.

Grigol Uratadze, a fellow prisoner, later described Stalin's appearance and behaviour in prison: "He was scruffy and his pockmarked face made him not particularly neat in appearance.... He had a creeping way of walking, taking short steps.... when we were let outside for exercise and all of us in our particular groups made for this or that corner of the prison yard, Stalin stayed by himself and walked backwards and forwards with his short aces, and if anyone tried speaking to him, he would open his mouth into that cold smile of his and perhaps say a few words... we lived together in Kutaisi Prison for more than half a year and not once did I see him get agitated, lose control, get angry, shout, swear - or in short - reveal himself in any other aspect than complete calmness."

At the Second Congress of the Social Democratic Labour Party held in London in 1903, there was a dispute between Lenin and Julius Martov over the future of the SDLP. Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters. Martov disagreed believing it was better to have a large party of activists. Leon Trotsky commented that "the split came unexpectedly for all the members of the congress. Lenin, the most active figure in the struggle, did not foresee it, nor had he ever desired it. Both sides were greatly upset by the course of events."

Although Martov won the vote 28-23 on the paragraph defining Party membership. With the support of George Plekhanov, Lenin won on almost every other important issue. His greatest victory was over the issue of the size of the Iskra editorial board to three, himself, Plekhanov and Martov. This meant the elimination of Pavel Axelrod, Alexander Potresov and Vera Zasulich - all of whom were "Martov supporters in the growing ideological war between Lenin and Martov".

Trotsky argued that "Lenin's behaviour seemed unpardonable to me, both horrible and outrageous. And yet, politically it was right and necessary, from the point of view of organization. The break with the older ones, who remained in the preparatory stages, was inevitable in any case. Lenin understood this before anyone else did. He made an attempt to keep Plekhanov by separating him from Zasulich and Axelrod. But this, too, was quite futile, as subsequent events soon proved."

As Lenin and Plekhanov won most of the votes, their group became known as the Bolsheviks (after bolshinstvo, the Russian word for majority), whereas Martov's group were dubbed Mensheviks (after menshinstvo, meaning minority). Stalin who was still in prison in Siberia, decided he favoured the Bolsheviks in this dispute. He escaped on 5th January 1904 and although suffering from frostbite he managed to get back to Tiflis six weeks later.

On this day in 1913 hunger striker Olive Wharry was released from prison. On 7th March 1913 she was found guilty of arson and it was reported by the Daily Mirror that "Wharry laughed when sentenced to eighteen months' imprisonment." Wharry made a statement in court where she attempted to explain her actions: "I deny that this court has any jurisdiction over me. A man has the right to be tried by his peers, and so, too, a woman should be tried by women. How can you expect women to obey laws which they have had no hand in making? Women are classed with imbeciles, aliens, and criminals, and are allowed the rights of citizenship. Many social matters come before Parliament which ought to be dealt with by women, but which are only considered by men… I am standing for a great principle and morally I am not guilty, though the jury have condemned me, therefore I shall hunger-strike."

It was claimed in court that the tea pavilion "was absolutely destroyed, and a heavy pecuniary loss has thrown upon the two ladies who held the refreshment contract". It was estimated that the loss suffered amounted to £400. It was reported on 26th April that Dr Oliver Robert Wharry was involved in a scuffle when the two solicitors' clerks, employed by the women with the refreshment contract, tried to serve a writ on his daughter. Wharry responded that "she was sorry that the contents of the building was the property of two ladies, she did not know this at the time, but would say to them that this was war, and in a war non-combatants had to suffer."

Olive Wharry went on hunger-strike and Dr Maurice Craig reported to the Home Office that she was "a very frail person, with a very defective circulation... her hands are cold and very blue; her pupils are widely dilated". (21) According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "She was released on 8th April after having been on hunger strike for 32 days, apparently without the prison authorities noticing. His usual weight was 7st 11lbs; when released she weighed 5st 9lbs."

On this day in 1935 the Works Progress Administration is established. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president he put his friend, Harry Hopkins, in charge of the Works Projects Administration (WPA). The purpose of the WPA was to give wages to people currently unemployed. By 1936 over 3.5 million people were employed on various WPA programs. This included the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the National Youth Administration (NYA) and the Public Works Administration (PWA) under Harold Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior.

On this day in 1943 Elise Hampel is executed in Berlin for her anti-Nazi activities. Elise Lemme was born in Bismark, Germany, on 27 October 1903. After finishing elementary school she worked as a domestic servant. She married Otto Hampel in 1935. Elise Hampel joined the National Socialist Frauenschaft (Women's League) in 1936, leading a group until 1940.

Elise Hampel changed her views on Adolf Hitler after her brother's death during the German assault on France. Opposed to what she now believed to be a war of aggression she began writing anti-Nazi postcards and leaflets and leaving them in mailboxes. They urged people to refuse to serve in the war and to overthrow Hitler.

The Hampels were arrested by the Gestapo on 20th October, 1942. Otto Hampel declared to the police that he was "happy with the idea" of protesting against Hitler and his regime. Otto and Elise Hampel were accused of "demoralizing the troops" and "preparation for high treason." They were found guilty and executed on 8th April, 1943.