On this day on 1st July

On this day in 1555 John Bradford was executed. John Bradford was born in Manchester in about 1510. According to his biographer, D. Andrew Penny. " His parents are said to have been of gentle birth, but little is known for certain of his family, except that he had at least three sisters. He attended Manchester grammar school, and was grateful for the rest of his life for the education he received there."

In 1544 Bradford was employed by Sir John Harington of Exton, Rutland, the vice-treasurer of the English army in France. In 1547 he enrolled at the Inner Temple. After hearing the preacher Hugh Latimer he decided to enroll as a divinity student at St Catharine's College in 1549. An impressive student he was given a fellowship at Pembroke Hall at Cambridge University.

On 10 August 1550 Nicholas Ridley, the Bishop of London, ordained him deacon, gave him a preaching licence, and appointed him one of his own chaplains. On 24 August 1551 he was made one of six chaplains to Edward VI. It was intended that at any one time two should be serving at court, while the others travelled through the country preaching reformation. "His effectiveness was greatest in southern Lancashire, where he spoke to large crowds and attracted a number of converts, though without making much impression upon the gentry of the region." John Foxe worked with Bradford during this period: "Bradford preached the gospel faithfully. He sharply reproved sin, sweetly preached Christ crucified, pithily spoke against heresies and errors, and earnestly persuaded his people to live godly lives."

On 13th August, 1553, accompanied by John Rogers, he acted to calm disturbances provoked by the Catholic Gilbert Bourne in a sermon at Paul's Cross. A few days after he had assisted the authorities in the task of crowd control he was summoned before the council in the Tower of London, and charged with preaching seditious sermons. So many Protestants were arrested that John Bradford had to share his apartment with Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley and Thomas Cranmer.

John Foxe later recalled: "Bradford was a tall, slender man with an auburn beard. He rarely slept more than four hours a night, preferring to spend his time in writing, preaching, or reading. Once or twice a week he would visit the common criminals in the prison and give them money to buy food or other comforts. One of his friends once asked Bradford what he would do if he was freed. Bradford said he would marry and hide in England while he continued to preach and teach the people."

On 4th February, 1555, Bradford's close friend, John Rogers was taken to Smithfield. His wife and children met him on the way to the burning, but Rogers still refused to recant. He told Sheriff Woodroofe: "That which I have preached I will seal with my blood." Woodroofe replied: "Then, you are a heretic. That will be known on the day of judgment." Just before the burning began a pardon arrived. However, Rogers refused to accept it and became the first martyr to suffer death during the reign of Queen Mary.

On 30th June 1555 John Bradford was told he was to executed the following day. "Thank God" he replied. "I've looked forward to this for a long time. The lord make me worthy." His execution was announced for four o'clock the next morning. "No one was sure why such an unusual hour was chosen, but if the authorities hoped the hour would discourage a crowd, they were disappointed. The people waited faithfully at Smithfield until Bradford was brought there at nine in the morning, led by an unusually large number of armed guards. Bradford fell to the ground to say his prayers then went cheerfully to the stake."

On this day in 1865 Georgina Brackenbury, the daughter of Hilda Brackenbury, and the sister of Marie Brackenbury. Her father, Charles Brackenbury, was an army general and two of her brothers died while serving in the armed forces.

Brackenbury studied at the Slade Art School from 1888 to 1900. A member of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) she joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in March 1907.

In February 1908, Georgina Brackenbury was arrested in February 1908 during a WSPU demonstration outside the House of Commons and was sentenced to six weeks in Holloway Prison.

On her release she spoke at meetings all over Britain. She also made a tour of Germany where she gave several speeches on the subject of women's suffrage. In 1909 she joined Annie Kenney, Elsie Howey, Clara Codd, Vera Wentworth, Mary Blathwayt and Mary Phillips the WSPUWest of England campaign. In 1910 she replaced Mary Gawthorpe as WSPU organizer in Manchester.

Georgina visited Eagle House near Batheaston on 22nd July 1910 with her sister Marie Brackenbury. Their host, was Mary Blathwayt, a fellow member of the WSPU. Her father Colonel Linley Blathwayt planted a tree, a Cupressus Macrocarpa Lutea, in her honour in his suffragette arboretum in a field adjacent to the house.

Christabel Pankhurst decided that the WSPU needed to intensify its window-breaking campaign. On 1st March, 1912, a group of suffragettes volunteered to take action in the West End of London. The Daily Graphic reported the following day: "The West End of London last night was the scene of an unexampled outrage on the part of militant suffragists.... Bands of women paraded Regent Street, Piccadilly, the Strand, Oxford Street and Bond Street, smashing windows with stones and hammers."

Georgina Brackenbury and her mother, were both arrested for taking part in the demonstration. Hilda Brackenbury, aged 79, was accused of breaking two windows in the United Service Institution in Whitehall. She served eight days on remand before being sentenced to 14 days in Holloway Prison. Georgina served four weeks in prison.

Mrs Brackenbury's home at 2 Campden Hill Square, London, became known as "Mouse Castle" as members of the WSPU went there to recuperate after being released under the Cat & Mouse Act.

In 1927 Georgina was commissioned by Margaret Haig Thomas to paint the portrait of Emmeline Pankhurst that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. According to Elizabeth Crawford, the author of The Suffragette Movement (1999): "It is thought to have been painted from life, although there is in existence a photograph (reproduced as a postcard) of Mrs Pankhurst, wearing exactly the same clothes and jewellery as appear in her portrait. However, the position of the figure differs and doubtless by then Mrs Pankhurst's finances did not allow her an extensive wardrobe."

Georgina Brackenbury died in 1949. The following year her sister, Marie Brackenbury, died. The last survivor of the immediate family, she left the house to the Over Thirties Association. The Suffragette Fellowship commissioned a plaque to be attached to the house. It read "The Brackenbury trio were so whole-hearted and helpful during all the early strenuously years of the militant suffrage movement. We remember them with honour."

On this day in 1884 Allan Pinkerton died. After his death the Pinkerton Detective Agency was run by his two sons, Robert Pinkerton and William Pinkerton. The brothers opened their fourth office in Denver. They appointed James McParland and Charlie Siringo to run the Pinkerton's western division.

Allan Pinkerton was born in Glasgow in Scotland in 1819. A cooper by trade he was active in the Chartist movement as a young man. Disillusioned by the failure to win universal suffrage, Pinkerton emigrated to the United States.

Pinkerton settled in Chicago and became a deputy-sheriff. In 1852 he formed the Pinkerton Detective Agency. The first detective agency in the United States, it solved a series of train robberies. In 1861 the agency was given the task of guarding Abraham Lincoln. While in Baltimore, while on the way to the inauguration, Pinkerton foiled a plot to assassinate the president.

The Pinkerton Detective Agency was a great success. On the facade of his three-story Chicago headquarters was the company slogan, "We Never Sleep". Above this was a huge, black and white eye. The Pinkerton logo was the origin of the term private eye. Pinkerton became head of the American secret service during the Civil War and led the pursuit for Jessie James.

In 1873 Franklin B. Gowen, president of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, had a meeting with Allan Pinkerton. Gowen had considerable investments in the coal-mines of Schuylkill County and feared that the trade union activities of John Siney and the Workingmen's Benevolent Association would result in lower profits.

Allan Pinkerton decided to send James McParland to Schuylkill County. Assuming the alias of James McKenna, he found work as a labourer in Shenandoah. Soon afterwards he joined the Workingmen's Benevolent Association and the Shenandoah branch of the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), an organisation for Irish immigrants run by the Roman Catholic clergy.

After a few months of investigations McParland reported back to Allan Pinkerton that some members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians were also active in the secret organization, the Molly Maguires. McParland estimated that the group had about 3,000 members. Each county was governed by a bodymaster who recruited members and gave out orders to commit crimes. These bodymasters were usually ex-miners who now worked as saloon keepers.

Over a two year period James McParland collected evidence about the criminal activities of the Molly Maguires. This included the murder of around fifty men in Schuylkill County. Many of these men were the managers of coal mines in the region.

John Kehoe, one of the leaders of the Molly Maguires became suspicious of McParland and began to investigate his past. McParland was tipped off that Kehoe was planning to murder him so he fled from the area.

In 1876 and 1877 James McParland was the star witness for the prosecution of John Kehoe and the Molly Maguires. Twenty members were found guilty of murder and were executed. This included Kehoe, a former union leader who was convicted of a murder that had taken place fourteen years previously.

On this day in 1896 Harriet Beecher Stowe died. Harriet Beecher, the daughter of the Congregationalist minister, Lyman Beecher, was born in Litchfield, Connecticut, on 14th June, 1811. Her brother was the famous preacher, Henry Ward Beecher. After an education at the Connecticut Female Seminary she taught at schools in Hartford and Cincinnati.

In 1834 Harriet began to write short stories for the Western Monthly. Two years later she married the Rev. Calvin Ellis Stowe, a clergyman and biblical scholar. Over the next few years Harriet had seven children but continued to write stories and articles for numerous magazines.

Harriet was converted to anti-slavery campaign after hearing Theodore Weld speak at a public meeting. She was determined to do something to help the cause. One day, while in church, she decided to write a novel about slavery. The main character in the book was based on Josiah Henson, an escaped slave whose narrative Harriet had read. Weld's book, American Slavery As It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses, also provided her with plenty of background material.

Uncle Tom's Cabin was written as a serial and began appearing in the anti-slavery journal, The National Era, in 1851. It was published in book form the following year. In the preface Stowe wrote: "The object of these sketches is to awaken sympathy and feeling for the African race, as they exist among us; to show their wrongs and sorrows, under a system so necessarily cruel and unjust as to defeat and do away with the good effects of all that can be attempted for them by their best friends."

The publisher decided to print 5,000 copies of Uncle Tom's Cabin. It was an immediate best-seller. The first edition sold out in seven days. Despite being banned in the South, over 300,000 copies were sold in its first year. As Frederick Douglass was later to point out: "Its effect was amazing, instantaneous and universal".

Translated into many languages, Uncle Tom's Cabin was also a great success in Europe. In England alone over a million copies were sold. Supporters of slavery were furious and Stowe received hundreds of hostile letters. Thirty pro-slavery novels were published in an attempt to reverse public sympathies in what had now become a propaganda battle. Stowe responded by publishing The Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1853), a book of source material on slavery.

Stowe visited England where she met Queen Victoria. She also made three tours of Europe and this inspired her book Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands (1854). A second anti-slavery novel, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp appeared in 1856. The story of a slave rebellion was followed by The Minister's Wooing (1859).

Other books written by Stowe include Agnes of Sorrento (1862), Oldtown Folks (1869) Pink and White Tyranny (1871) and We And Our Neighbours (1875).

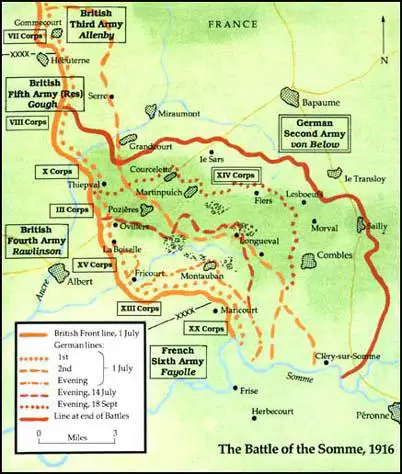

On this day in 1916 was the first day of the Battle of the Somme. It was planned as a joint French and British operation. The idea originally came from the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre and was accepted by General Douglas Haig, the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commander, despite his preference for a large attack in Flanders. Although Joffre was concerned with territorial gain, it was also an attempt to destroy German manpower.

Morale in Britain was at an all-time low. "Haig needed a breakthrough to boost the flagging spirits of a country still in principle fully behind the war, patriotic and pressing for military victory." After a meeting with the French Commander-in-Chief, Joseph Joffre, it was decided to mount a joint offensive where the British and French lines joined on the Western Front. According to Basil Liddell Hart, the decision by Joffre to make this sector, considered to be the German's strongest, "seems to have been arrived at solely because the British would be bound to take part in it."

Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, was told about the plan when he visited General Haig in May 1916. He agreed to give his full support in his newspapers to the offensive. One of his biographers, S. J. Taylor, points out: "Northcliffe... at last capitulated, the Daily Mail descending into the propagandistic prose that came to characterize the reporting of the First World War. It was a style long since adopted by his competitors; stirring phrases, empty words, palpable lies."

At first Joffre intended for to use mainly French soldiers but the German attack on Verdun in February 1916, turned the Somme offensive into a large-scale British diversionary attack. General Haig now took over responsibility for the operation and with the help of General Sir Henry Rawlinson, came up with his own plan of attack. Haig's strategy was for a eight-day preliminary bombardment that he believed would completely destroy the German forward defences. He told his General Staff that "the advance was to be pressed eastward far enough to enable our cavalry to push through into the open country beyond the enemy's prepared lines of defence."

General Haig wrote that he was convinced that the offensive would win the war: "I feel that every step in my plan has been taken with the Divine help". General Henry Rawlinson was was in charge of the main attack and his Fourth Army were expected to advance towards Bapaume. To the north of Rawlinson, General Edmund Allenby and the British Third Army were ordered to make a breakthrough with cavalry standing by to exploit the gap that was expected to appear in the German front-line. Further south, General Émile Fayolle was to advance with the French Sixth Army towards Combles. Rawlinson wrote: "DG (Haig) tells me that we are to attack, that the French are doing likewise and making a supreme effort. It will cost us dearly, and we shall not get very far."

The Battle of the Somme began in early hours of the 1st July 1916, when nearly a quarter of a million shells were fired at the German positions in just over an hour, an average of 3,500 a minute. So intense was the barrage that it was heard in London. At 7.28 a.m. ten mines were exploded under the German trenches. Two minutes later, British and French troops attacked along a 25-mile front. The main objective was "to break through the German lines by means of a massive infantry assault, to try to create the conditions in which cavalry could then move forward rapidly to exploit the breakthrough."

On the first day of the battle thirteen British divisions went "over the top" in regular waves. The bombardment failed to destroy either the barbed-wire or the concrete bunkers protecting the German soldiers. This meant that the Germans were able to exploit their good defensive positions on higher ground. "The attack was a total failure. The barrage did not obliterate the Germans. Their machine guns knocked the British over in rows: 19,000 killed, 57,000 casualties sustained - the greatest loss in a single day ever suffered by a British army and the greatest suffered by any army in the First World War. Haig had talked beforehand of breaking off the offensive if it were not at once successful. Now he set his teeth and kept doggedly on - or rather, the men kept on for him."

On this day in 1934 Ernst Röhm is murdered. Industrialists such as Albert Voegler, Gustav Krupp, Alfried Krupp, Fritz Thyssen and Emile Kirdorf, who had provided the funds for the Nazi victory, were unhappy with Röhm's socialistic views on the economy and his claims that the real revolution had still to take place. Walther Funk reported that Hjalmar Schacht and his friends in big business were worried that the Nazis might begin "radical economic experiments".

General Werner von Blomberg, Hitler's minister of war, and Walther von Reichenau, chief liaison officer between the German Army and the Nazi Party, became increasingly concerned about the growing power of Ernst Röhm and the Sturmabteilung (SA). They feared that the SA was trying to absorb the regular army in the same way that the SS had taken over the political police. Reichenau was concerned by a letter he received from Röhm: "I regard the Reichswehr now only as a training school for the German people. The conduct of war, and therefore of mobilization as well, in the future is the task of the SA."

Many people in the party disapproved of the fact that Röhm, and many other leaders of the SA, including his deputy, Edmund Heines, were homosexuals. Konrad Heiden, a German journalist who investigated these rumours later claimed that Heines was at the centre of this homosexual ring. "The perversion was wide-spread in the secret murderers' army of the post-war period, and its devotees denied that it was a perversion. They were proud, regarded themselves as 'different from the others', meaning better."

However, Hitler allowed him to continue in his post. According to Ernst Hanfstaengel, during this period, Hitler was frightened of Röhm because Karl Ernst had information about the leader's sexuality: "Ernst, another homosexual SA officer, hinted in the early 1930s that a few words would have sufficed to silence Hitler had he complained about Röhm's behavior."

Hermann Göring, Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler were all concerned with the growing power of Röhm, who continued to make speeches in favour of socialism. As Peter Padfield has pointed out, the Sturmabteilung (SA) "now a huge, heterogeneous and generally discontent army of four million, threatened the hereditary leadership of the Army, the Junker landowners, the bureaucracy, and the heavy industrialists" with talk of a second revolution.

Göring suggested to Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo, that he was too close to Röhm. "I warn you, Diels, you can't sit on both sides of the fence." Göring ordered Diels to carry out an investigation into Röhm and the SA. He reported back with details of homosexual rings centering on Röhm and other SA leaders, and on their corruption of Hitler Youth members. Göring complained to Diels: "This whole camarilla around Chief of Staff Röhm is corrupt through and through. The SA is the pacemaker in all this filth (in the Hitler Youth movement). You should look into it more thoroughly."

Diels presented his report to Adolf Hitler in January 1934 at his retreat at Obersalzberg. Diels provided information that Röhm had been conspiring with Gregor Strasser and Kurt von Schleicher against the government. It was also suggested that Röhm had been paid 12 million marks by the French to overthrow the Nazi government. Hitler was furious and stated that "it is incomprehensible that Strasser and Schleicher, these arch-traitors, have survived to this day." After the meeting had ended Göring turned to Diels and said: "You understand what the Führer wants? These three must disappear and very soon." He added that Strasser "can commit suicide - he is a chemist after all".

Richard Overy has claimed that both Strasser and Von Schleicher were both politically inactive and posed no threat to Hitler. Peter Stachura, the author of Gregor Strasser and the Rise of Nazism (1983) believes that Strasser was faithfully keeping a written promise to Hitler that he would renounce politics, shunning his former political associates and doing everything possible to deny rumours that he was involved in any conspiracy.

In February, 1934, Hitler had a meeting with Group Captain Frederick Winterbotham. Hitler told him that there should be only three major powers in the world, the British empire, the American empire and the future German empire. "All we ask is that Britain should be content to look after her empire and not interfere with Germany's plans of expansion." He then went on to deal with the subject of Communism. "He stood up and, as if he was an entirely different personality, he started to yell in a high-pitched staccato voice... He ranted and raved against the Communists." It was later speculated that Hitler was letting Britain know he intended to purge the left-wing of the Nazi Party.

Heinrich Himmler and Karl Wolff went to visit Ernst Röhm at the SA headquarters at the end of April. According to Wolff he "implored Röhm to dissociate himself from his evil companions, whose prodigal life, alcoholic excesses, vandalism and homosexual cliques were bringing the whole movement into disrepute". He then said with moist eyes, "do not inflict me with the burden of having to get my people to act against you". Röhm, also with tears in his eyes, thanked his old comrade for giving him this warning.

On 4th June, 1934, Hitler held a five-hour meeting with Röhm. According to Hitler's account he told Röhm that he had heard that "certain conscienceless elements were preparing a Nationalist-Bolshevik revolution, which could lead only to miseries beyond description". Hitler informed Röhm that some people suspected that he was the leader of a group who "praise the Communist paradise of the future, which, in reality, would only lead to a battle for Hell."

After the meeting Ernst Röhm told friends that he was convinced that he could rely on Hitler to take his side against "the gentlemen with uniforms and monocles". Louis L. Snyder argues that Hitler had in fact decided to give his support to Röhm's enemies: "Hitler later alleged that his trusted friend Röhm had entered a conspiracy to take over political power. The Führer was told, possibly by one of Röhm's jealous colleagues, that Röhm intended to use the SA to bring a socialist state into existence... Hitler came to his final decision to eliminate the socialist element in the party."

On 11th June 1934, Hjalmar Schacht had a private meeting with the Governor of the Bank of England, his personal friend and business associate, Montagu Norman. Both men were members of the Anglo-German Fellowship group and shared a "fundamental dislike" of the "French, Roman Catholics, Jews". Schacht told Norman that there would be no "second revolution" and that the SA were about to be purged.

Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, Hermann Göring and Theodore Eicke worked on drawing up a list of people who were to be eliminated. It was known as the "Reich List of Unwanted Persons". (89) The list included Ernst Röhm, Edmund Heines, Karl Ernst, Hans Erwin von Spreti and Julius Uhl of the SA, Gregor Strasser, Kurt von Schleicher, Hitler's predecessor as chancellor, Gustav von Kahr, who crushed the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, Herbert von Bose and Edgar Jung, two men who worked for Franz von Papen and Fritz Gerlich, a journalist who had investigated the death of Hitler's niece, Geli Raubal.

Also on the list was Erich Klausener, the President of the Catholic Action movement, who had been making speeches against Hitler. It was feared that he was building up a strong following from within the Catholic Church. On 24th June, 1934, Klausener had organized a meeting held at Hoppegarten racecourse, where he spoke out against political oppression in front of an audience of 60,000.

On the evening of 28th June, 1934, Hitler telephoned Röhm to convene a conference of the SA leadership at Hanselbauer Hotel in Bad Wiesse, two days later. "The call served the double purpose of gathering the SA chiefs in one out-of-the-way spot, and reassuring Röhm that, despite the rumours flying about, their mutual compact was safe. No doubt Röhm expected the discussion to centre on the radical change of government in his favour promised for the autumn."

The following day Hitler held a meeting with Joseph Goebbels. He told him that he had decided to act against Röhm and the SA. Hitler felt he could not take the risk of "breaking with the conservative middle-class elements in the Reichswehr, industry, and the civil service". By eliminating Röhm he could make it clear that he rejected the idea of a "socialist revolution". Although he disagreed with the decision, Goebbels decided not to speak out against "Operation Humingbird" in case he was also eliminated.

On 29th June, Karl Ernst got married and as he planned to go on his honeymoon and therefore could not attend the SA meeting at the Hanselbauer Hotel. Ernst Röhm and Hermann Göring both attended the wedding. Later that day he alerted the Berlin SA that he had heard rumours that there was a danger of a putsch against Hitler by the right-wing of the party.

At around 6.30 in the morning of 30th June, Hitler arrived at the hotel in a fleet of cars full of armed Schutzstaffel (SS) men. (96) Erich Kempka, Hitler's chauffeur, witnessed what happened: "Hitler entered Röhm's bedroom alone with a whip in his hand. Behind him were two detectives with pistols at the ready. He spat out the words; Röhm, you are under arrest. Röhm's doctor comes out of a room and to our surprise he has his wife with him. I hear Lutze putting in a good word for him with Hitler. Then Hitler walks up to him, greets him, shakes hand with his wife and asks them to leave the hotel, it isn't a pleasant place for them to stay in, that day. Now the bus arrives. Quickly, the SA leaders are collected from the laundry room and walk past Röhm under police guard. Röhm looks up from his coffee sadly and waves to them in a melancholy way. At last Röhm too is led from the hotel. He walks past Hitler with his head bowed, completely apathetic."

Edmund Heines was found in bed with his chauffeur and other SA men were found in compromising situations. Heines and his boyfriend were dragged out and shot on the road. (98) Joseph Goebbels complained about the "revolting, almost nauseating scenes". At the Munich railroad station, the SA leaders were beginning to arrive. As they alighted from the incoming trains they were taken into custody by SS troops. It is estimated that about 200 senior SA officers were arrested during that day. All of them were taken to Stadelheim Prison.

One of Röhm's boyfriends, Karl Ernst, and the head of the SA in Berlin, had just married and was driving to Bremen with his bride to board a ship for a honeymoon in Madeira. His car was overtaken by Schutzstaffel (SS) gunman, who fired on the car, wounding his wife and his chauffeur. Ernst was taken back to SS headquarters and executed later that day.

A large number of the SA officers were shot as soon as they were captured but Adolf Hitler decided to pardon Ernst Röhm because of his past services to the movement. However, after much pressure from Göring and Himmler, Hitler agreed that Röhm should die. Himmler ordered Theodor Eicke to carry out the task. Eicke and his adjutant, Michael Lippert, travelled to Stadelheim Prison in Munich where Röhm was being held. Eicke placed a pistol on a table in Röhm's cell and told him that he had 10 minutes in which to use the weapon to kill himself. Röhm replied: "If Adolf wants to kill me, let him do the dirty work."

According to Paul R. Maracin, the author of The Night of the Long Knives: Forty-Eight Hours that Changed the History of the World (2004): "Ten minutes later, SS officers Michael Lippert and Theodor Eicke appeared, and as the embittered, scar-faced veteran of verdun defiantly stood in the middle of the cell stripped to the waist, the two SS officers riddled his body with revolver bullets." Eicke later claimed that Röhm fell to the floor moaning "Mein Führer".

On this day in 1999 film director Edward Dmytryk died. Edward Dmytryk was born in British Columbia, Canada, on 4th September, 1908. After an education at the California Institute of Technology, he became a messenger boy at Paramount Pictures.

Dmytryk became a film editor in 1929 and directed his first film, The Hawk, in 1935. Over the next eight years he directed 23 films. This included Mystery Sea Raider (1940), Her First Romance (1940), Golden Gloves (1940) Secrets of the Lone Wolf (1941), The Blonde from Singapore (1941), Sweetheart of the Campus (1941), Under Age (1941), The Devil Commands (1941), Counter-Espionage (1942), Confessions of Boston Blackie (1941) and Seven Miles from Alcatraz (1942).

Dmytryk joined the American Communist Party in 1944. He later claimed that the main reason he joined was that he wanted to end world poverty. During this period he was involved in making several politically oriented films such as the anti-fascist Hitler's Children (1943). Murder, My Sweet (1944) was a film where he helped to create the genre later known as "film noir". Crossfire (1947) was one of the first Hollywood movies to tackle anti-Semitism, won four Academy Awards.

After the Second World War the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. In 1947 19 members of the film industry were called to appear before the HUAC. This included Dmytryk, Herbert Biberman, Alvah Bessie, Lester Cole, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz, John Howard Lawson, Larry Parks, Waldo Salt, Bertolt Brecht, Richard Collins, Gordon Kahn, Robert Rossen, Lewis Milestone and Irving Pichel.

Dmytryk appeared before the HUAC on 29th October, 1947, but like Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, refused to answer questions about his membership of the Screen Directors Guild or the American Communist Party. Known as the Hollywood Ten, they claimed that the 1st Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to do this.

The chairman of the HUAC, J. Parnell Thomas, refused permission for Dmytryk to make a statement about his political views. This was later published in Hollywood on Trail (1948): "It is my firm belief that democracy lives and thrives only on freedom. This country has always fulfilled its destiny most completely when its people, through their representatives, have allowed themselves the greatest exercise of freedom with the law. The dark period in our history have been those in which our freedoms have been suppressed, to however small a degree. Some of that darkness exists into the present day in the continued suppression of certain minorities."

Dmytryk then went on to argue that he believed that the main reason he was before the HUAC was because he made Crossfire (1947), an attack on anti-Semitism. "In my last few years in Hollywood, I have devoted myself, through pictures such as Crossfire, to a fight against these racial suppressions and prejudices. My work speaks for itself. I believe that it speaks clearly enough so that the people of the country and this Committee, which has no right to inquire into my politics or my thinking, can still judge my thoughts and my beliefs by my work, and by my work alone."

Dmytryk, Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Dalton Trumbo, Lester Cole, Ring Lardner Jr., Samuel Ornitz and John Howard Lawson, were all found guilty of contempt of Congress and given the maximum sentence of a year in prison. The case went before the Supreme Court in April 1950, but with only Justices Hugo Black and William Douglas dissenting, the sentence was confirmed and Dmytryk spent twelve months in Mill Point Federal Prison, West Virginia.

Blacklisted by the Hollywood studios, he moved to England where he directed two films, Obsession (1949) and Give Us This Day (1949). However, Dmytryk had financial problems as a result of divorcing his first wife. Faced with having to sell his plane and encouraged by his new wife, Dmytryk decided to try to get his name removed from the blacklist. Dmytryk's first move was to meet with a journalist, Richard English, who specialized in writing anti-communist articles for the American press. With English's help, Dmytryk wrote What Makes a Hollywood Communist? for the Saturday Evening Post (17th May, 1951). This explained how he now completely rejected his communist past.

On 17th April, 1951, Dmytryk appeared before the House of Un-American Activities Committee again. This time he answered all their questions including the naming of twenty-six former members of left-wing groups. This included Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Albert Maltz, Adrian Scott, Lester Cole, John Howard Lawson, Gordon Kahn, Richard Collins, Jules Dassin, Jack Berry,John Wexley, Michael Gordon, Michael Uris and Bernard Vorhaus. Dmytryk also revealed how Lawson, Scott and Maltz had put him under pressure to make sure his films expressed the views of the American Communist Party. This was particularly damaging as several members of the original Hollywood Ten were at that time involved in court cases with their previous employers.

Dmytryk later recalled: "Not a single person I named hadn't already been named at least a half-dozen times and wasn't already on the blacklist. Because I didn't know that many. I only knew a few people, literally a handful of people, all of whom had been in the Party long before I was, all of whom were known by the FBI and were known to the Committee. There was no question about that. With me it was that defending the Communist Party was something worse than naming the names. I did not want to remain a martyr to something that I absolutely believed was immoral and wrong. It's as simple as that."

Edward Dmytryk then resumed his Hollywood career and after making The Sniper (1952) he directed The Caine Mutiny (1954). Lary May, the author of The Big Tomorrow: Hollywood and the Politics of the American Way (2000) has pointed out: "Edward Dmytryk directed, The Caine Mutiny (1954) to atone for his own communist activities. Significantly the story evoked memories of the Depression-era classic, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935). Where the earlier film justified the revolt of oppressed sailors against injustice, The Caine Mutiny portrayed rebels as an irrational mob of 'immature men'. No doubt this was the reason, explained the producers, that the Navy cooperated in producing a war film that would justify their system."

Other films made by Dmytryk included The Young Lions (1958), Walk on the Wild Side (1962), The Carpetbaggers (1963), Mirage (1965) and The Battle for Anzio (1968). His autobiography, It's a Hell of a Life, was published in 1978. He is also the author of Odd Man Out: A Memoir of the Hollywood Ten.

Edward Dmytryk died in Encino, California, on 1st July, 1999.