The Coal Industry and First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, the former miner's leader, Keir Hardie tried to organize a national strike against Britain's participation in the war. He issued a statement that argued: "The long-threatened European war is now upon us. You have never been consulted about this war. The workers of all countries must strain every nerve to prevent their Governments from committing them to war. Hold vast demonstrations against war, in London and in every industrial centre. There is no time to lose. Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!" (1)

Arthur J. Cook, a leading figure in the MFGB in South Wales was a strong opponent of the war. He was especially angry about the willingness of the government to spend such large sums on the military where they had been slow to deal with the problems of working-class poverty. In one article for the Porth Gazette, he argued "we must do our duty as trade unionists and as citizens to force the Government, who in one night could vote £100 millions for destruction of human life to see that justice is meted out to these unfortunates". (2)

It was very important for the government to avoid strikes during the war and with the help of the Labour Party and the Trade Union Congress an "Industrial Truce" was announced. A further agreement in March 1915, committed the unions for the duration of hostilities to the abandonment of strike action and the acceptance of government arbitration in disputes. In return the government announced its limitation of profits of firms engaged in war work, "with a view to securing that benefits resulting from the relaxation of trade restrictions or practices shall accrue to the State". (3) A. J. P. Taylor, has described these measures as "war socialism". (4)

At the beginning of the war miners were the largest single group of industrial workers in Britain. Coal production increased during the first few months of the conflict. This was mainly due to a greater commitment of the labour force in maximizing output. However, by March 1915, 191,170 miners joined the armed forces. "This was 17.1 per cent of the men engaged in the industry at the beginning of the war and constituted approximately 40 per cent of the miners of military age, 19-38." (5)

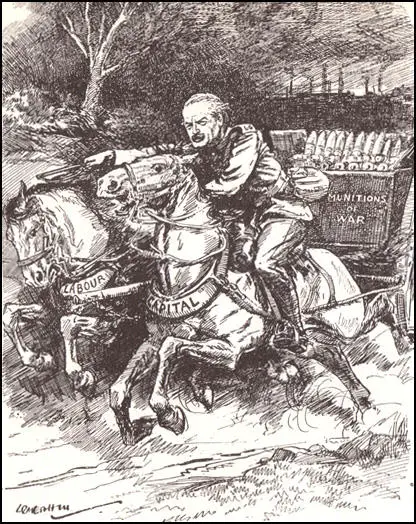

The Munitions of War Act was passed by Parliament in 1915 and provided for compulsory arbitration and virtually prohibited all strikes and lockouts. The Act also prohibited any change in the level of wages and salaries in "controlled" establishments without the consent of the Minister of Munitions. In those industries important to the war effort, it forbade workers in those establishments to leave their job without a "certificate of leave". The Labour movement was strongly opposed to this measure but was endorsed by the leadership of the TUC and the Labour Party. (6)

In March 1915 the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB) demanded a twenty per cent wage increase to compensate for inflation. The coal owners refused to discuss a national wage rise, and negotiations reverted to the districts. Agreements were arrived at satisfactorily in most areas, but in South Wales the owners were only willing to offer ten per cent. In July the miners in South Wales went on strike. (7)

Walter Runciman, the President of the Board of Trade, met with miners leaders but was unable to obtain an agreement. H. H. Asquith, considered using the Munitions of War Act, which effectively made strike action illegal. David Lloyd George warned against this and he negotiated a settlement that quickly conceded nearly all of the miners demands. This included a 18½ per cent wage increase. (8)

Lloyd George now made regular visits to British mining areas giving patriotic speeches about the importance of coal for the war effort and stressing that the miners should work harder in order to maximize output. He argued that "every extra wagon load would bring the war to a more speedy conclusion". In one speech he pointed out: "In peace and war King Coal is the paramount lord of the industry... In wartime it is life for us and death for our foes." (9)

In November 1916, another strike over pay took place in Wales. This time the government agreed to Runciman's proposal that "the government by regulation under the Defence of the Realm Act assume power to take over any of the collieries of the country, the power to be exercised in the first instance in South Wales". It was decided to take full control over shipping, food and the coal industry. Alfred Milner was appointed as Coal Controller. It has been argued that "instigating control of one of Britain's major staple industries was an unprecedented move by the state." (10)

Milner issued his first report on 6th November 1916 and recognizing the gravity of the problem by recommending the immediate freezing of coal prices and suggesting the establishment of a Royal Commission to considering the future of the coal industry. Lloyd George argued that "the control of the mines should be nationalized as far as possible". (11) He acknowledged that this was a new political development and commented that the government had a choice, it needed "to abandon Liberalism or to abandon the war". (12)

The government became very concerned about the activities of Arthur J. Cook, the leader of the miners in the Rhondda. The high casualty-rate during 1916, especially at the Somme Offensive, prompted the government to draft men from essential industries who had hitherto been exempt from conscription. It was decided to take 20,000 miners from the pits and put them in the army. Cook took steps to obstruct the military's attempts to recruit men and posted notices at the local collieries advising miners to disobey instructions to report for army examination. Captain Lionel Lindsay, Chief Constable of Glamorgan applied to the Home Office to have him prosecuted but worried it would result in a strike the suggestion was turned down. (13)

At a mass meeting on 15th April 1917, Cook called for "peace by negotiations". In an article in The Merthyr Pioneer, he argued: "I am no pacifist when war is necessary to free my class from the enslavement of capitalism... As a worker I have more regard for the interests of my class than any nation. The interests of my class are not benefited by this war, hence my opposition. Comrades, let us take heart, there are thousands of miners in Wales who are prepared to fight for their class. War against war must be the workers' cry." (14)

Arthur J. Cook welcomed the Russian Revolution and according to a MI5 agent he told one meeting: "To hell with everybody bar my class. To me, the hand of the German and Austrian is the same as the hand of my fellow-workmen at home. I am an internationalist. Russia has taken the step, and it is due to Britain to second the same and secure peace and leave the war and its cost to the capitalist who made it for the profiteer." (15)

In November, 1917, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan once again reported the activities of Cook to the Home Office: "It was only reported to me by a Recruiting Officer last night that A. J. Cook, the agitator from the Lewis-Merthyr Colliery, Trehafod, Glamorgan, who I have frequently reported for disloyal utterances, without success, openly declared, whilst denouncing the Recruiting Authorities at Pontypridd, that if he decided that a man should not join the Army the Military Authorities would not dare to send him... Anyone with the slightest knowledge of human nature must be well aware that to punish a conceited upstart of this type, especially when he is a man of no real influence, like Cook, always gives universal satisfaction." (16)

Cook continued to make speeches against the war. When he visited the village of Ynyshir he called on miners to do what they could to bring the war to an end: "Are we going to allow this war to go on? The government wants a hundred thousand men. They demand fifty thousand immediately, and the Clyde workers would not allow the government to take them. Let us stand by them, and show them that Wales will do the same. I have two brothers in the army who were forced to join, but I say No! I will be shot before I go to fight. Are you going to allow us to be taken to the war? If so, I say there will not be a ton of coal for the navy." (17)

Once again Captain Lionel Lindsay contacted the Home Office: "As promised I enclose a list of the ILP and advanced Syndicalists employed at our collieries, who are really the cause of a good deal of the trouble in this part of the coalfield, not only at our own collieries, but also in the neighbourhood. Of this lot, Cook is by far the most dangerous. As he considers himself an orator he has most to say at the various meetings in the district, and without exception, the policy which he preaches is the down-tool policy, and he is also concerned with the peace-cranks." (18)

In March 1918 the Home Office acceded to Lindsay's pressure and Cook as arrested and charged with sedition, Charged under the Defence of the Realm Act and was found guilty "of making statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty among the civilian population" and was sentenced to three months' imprisonment. Miners in the Rhondda threatened strike action and Cook was released after serving only two months. (19)

Coal production fell dramatically between 1916-1918. J. F. Martin, the author of The Government and the Control of the British Coal Industry, 1914-1918 (1981) pointed out: "The decline in the amount of coal extracted per man-shift and the reduction in the number of shifts worked per year were part of a common cause, namely the decline in the physical ability of the male workers in the industry. To a large extent this was an inevitable legacy of the recruitment of large numbers of men in the early stages of war. Most of the miners who enlisted were in fact the youngest and fittest members of the industry. Thus it can be rightly assumed that their removal had a disproportionate effect on the remaining men's ability to produce coal, apart from the fact that the industry lost its highest productivity workers." (20)

Primary Sources

(1) Roy Hattersley, David Lloyd George (2010)

On 16 June 1915 he showed the Trades Union Congress a draft of his Munitions of War Bill. The gesture was a threat rather than a courtesy. A week later, he told the House of Commons that the trade unions had seven days to agree procedures by which the vacancies in ammunition factories could be filled. "Tomorrow morning the seven days begins ... If we cannot, by voluntary means, get the labour which is essential to this country in a war on which its life depends we must use, as an ultimate resort, the means which every state has at its command to save its life." Although he never used the word "compulsion", that was the expedient which his impatience demanded and which he chose to justify in an inexplicable outburst of political philosophy. "We talk about the state as if it were something apart from the workman. The workman is the state." In calmer moments he remembered how few workmen had a vote.

In September 1915, he addressed the TUC's annual conference in Bristol. "The government", he told them, "cannot win without you." Unfortunately the blandishments were not matched by the slightest understanding of the time-served craftsman's psychology. It was true that, because there was a shortage of skilled labour, there was no "question of turning out the skilled workmen in order to put cheaper workmen in his place". But "a good deal of work which was being done by skilled workmen [could] just as easily be done by those who had only a few weeks or a few days' training'." Craftsmen do not want to hear that their jobs do not require as much skill as they claim. Pride, though it comes second to pay, is something to be protected, like employment, against dilution.

The speech ended with the promise that sacrifices by working men would not "inure to the enrichment of individual capitalists, but entirely to the benefit of the state... We have declared 715 establishments, producing munitions of war, to be controlled establishments... They are only to get standard payments, based on the profit made before the war." That arrangement was augmented by the excess-profits tax which McKenna introduced in his autumn Budget. Nevertheless, arms manufacturers became the archetypal hard-faced men who did well out of the war.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Sinking of the Lusitania (Answer Commentary)