Joseph Southall

Joseph Edward Southall, the son of Joseph Sturge Southall (1835–1862) and Elizabeth Maria Baker (1833–1922) was born in Nottingham on 23rd August 1861. Both his parents were members of the Society of Friends. His father, a wholesale grocer, died the following year aged 27. His mother took him to Edgbaston, Birmingham, to live with his maternal grandmother. (1)

In 1872 Southall went to the Friends' School at Ackworth. Two years later he moved to the Friends' School in Bootham where he was taught watercolour painting by Edwin Moore, the brother of Henry Moore. (2)

In September 1878, a few days after his seventeenth birthday, he entered the offices of the Birmingham architectural partnership of Martin and Chamberlain, where he was to work for the next four years. During these years he pursued his art studies at evening classes at the Osler Street Board School. (3)

Southall and his mother toured Italy, where he studied the work of the early masters; this inspired his experiments with tempera, a technique in which he led a significant revival. He later wrote: "The thrill of joy which I experienced when, without any knowledge of what I was about to see, I stepped inside the enchanting cloisters of the great Campo Santo of Pisa. There I found myself at 21 years of age face to face with a vast series of frescoes, so quiet and yet so gay, so reticent in manner and so lively in essence that words must ever fail to convey even the faintest expression of what I felt." (4)

Joseph E. Southall - Artist

In 1882 Southall began attending the Birmingham School of Art. The following year he met fellow student, Arthur Gaskin. Both men joined the Birmingham Group, an informal collective of painters and craftsmen associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement that had been inspired by the ideas of historian Thomas Carlyle, art critic John Ruskin, and philosopher William Morris. All of its members studied or taught at the Birmingham School of Art after the reorganisation of its teaching methods by Edward R. Taylor. (5)

Joseph Southall was close to his first cousin, Anna Elizabeth Baker, the eldest daughter of Anna Jane Brady (1834-1893) and John Edward Baker (1828-1908), was born in King’s Norton, Worcestershire on 1st February 1859. John Baker a member of the Society of Friends ran a large blacking factory in Birmingham. A Quaker philanthropist, John Baker, was a member of Temperance Society and the Liberal Party and served as a Councillor on Birmingham Town Council. John’s elder brother George Baker (1825-1910), replaced Joseph Chamberlain as Mayor of Birmingham in June, 1876. (6)

Anna Baker had four younger siblings. On 21st July 1884 one of her sisters, Margaret, aged 22, and her cousin, Lilian Baker, aged 20, were drowned whilst bathing together at Llanaber North Wales. According to a local newspaper: "On the shore under Llanaber Church... where the beach is almost as smooth as a lawn, and the slope seawards nearly imperceptible... In comparatively shallow water, within a short distance of the land, and in sight of their relatives, two young lady visitors from Birmingham were drowned while bathing, and their bodies washed ashore." (7)

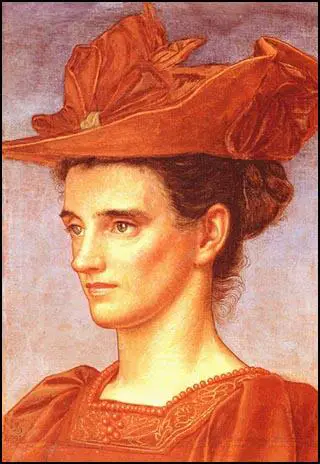

Later that year Joseph Southall went on a riding tour of the Midlands with Anna Elizabeth Baker. At this time he began painting portraits of Anna. An important influence was Hans Holbein. Southall made a special study of Holbein's drawings at Basle. He regarded his portraits as one of his major achievements. George Breeze argues: "The tempera technique is used here as a means of capturing the sitter's character, and not simply as an end in his own right. On the other hand the painstaking nature of this technique can lead to an air of frozen monumentality in Southall's portrayal of his sisters." (8)

Southall began to exhibit regularly at the annual exhibitions held by municipal art galleries and the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. Having become firmly established as a tempera painter. Tempera had been universally used until the introduction of oil in the early fifteenth century. "It is a medium in which the labour of preparation and the technique of execution needed to be rediscovered. Tempera is applied not directly to a board or canvas but to a layer of plaster or gesso that has been painstakingly prepared. The painting is done in several layers, each awaiting the drying of its predecessor. Painting in tempera is beset with hazards which Southall seemed to relish such as the problems of the variable water content of the egg with which the pigment is bound, the consequences of flaking, water bubbles and mould, the need to apply the paint in successive layers and so on." (9)

In 1891 Southall began receiving lessons from William Blake Richmond. He also became friends with Edward Burne-Jones who introduced him to William Morris. Burne-Jones and Morris encouraged Southall to continue with tempera painting. (10) Southall mixed the tempera to his own recipe and even collected and prepared some of his own pigments. Southall is said by his acquaintances to have kept his own chickens with the express purpose of ensuring a constant supply of egg yolks for his tempera." (11) Southall joined other artists to form the Society of Painters in Tempera. Other members included Walter Crane, Mary Sargant Florence, Roger Fry and Christiana Herringham. (12)

Southall recognised that most surviving Italian tempera paintings were painting on wooden panels, so his earliest efforts were done on some panels cut from an old door. He pained the panels "in the ordinary house-painter's manner with cream-coloured oil paint". Unfortunately the tempera began to peel and flake from the greasy and insufficiently porous surface. Later, he discovered that he needed to coat the panels with gesso (hydrated calcium sulphate). He "applied 6 or 8 coats to the panel" which was "finished smooth like ivory, and washed with weak size to stop absorbancy". (13)

In 1895 he painted a portrait of Anna Elizabeth Baker entitled The Coral Necklace. "The portrait provides a unique document of Southall's working methods, no other known painting of his bearing so many notes. In this documentation he was following the practice of the Pre-Raphaelite painters... The title is most apposite, since it is the coral necklace that gives the colour key to the whole portrait." (14)

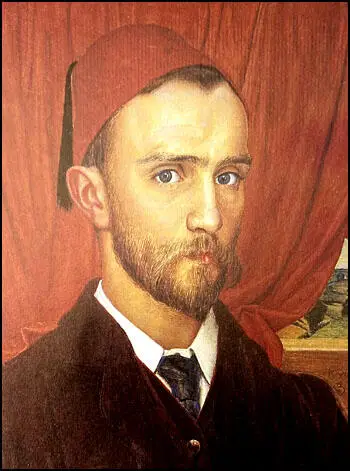

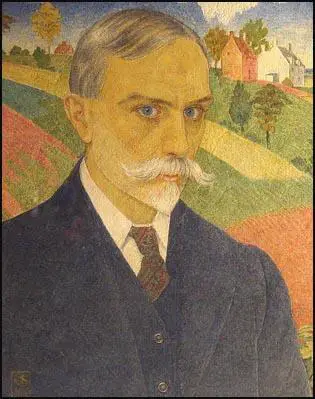

In a letter to Edward Burne-Jones he wrote: "In the Autumn of 1896 I painted my small portrait of myself called Man with a Sable Brush in tempera on panel as a trial trip in the egg medium which I had abandoned from 1889 to 1895 but now I seemed to master the medium and greatly like its rich qualities so that from that time I adopted it as my own." (15)

Joseph Southall thought one of his best paintings was the portrait of his mother, Elizabeth Baker Southall. The white cap, a symbol of widowhood, is an example of the Greek lace the artist designed and his mother worked. Sothall regarded it as one of his major achievements and the work he most wished to be in a national collection. It was offered to the Tate Gallery but was turned down by the Trustees and was subsequently bought for the Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. (16)

In June 1903 Joseph Southall married Anne Elizabeth Baker. Joseph and Anne (known as Bessie) lived at 13 Charlotte Road, Edgbaston, a house which belonged to his uncle, George Baker, which was to be his home for the rest of his life. Although both were fond of children they made a conscious decision not to have any themselves. (17) According to Peyton Skipwith: "She (Anne) was forty-four and he nearly forty-two; they had been intimate friends and companions for many years and had always intended to marry, but because of their close kinship had consciously waited until she was passed child-bearing age." (18)

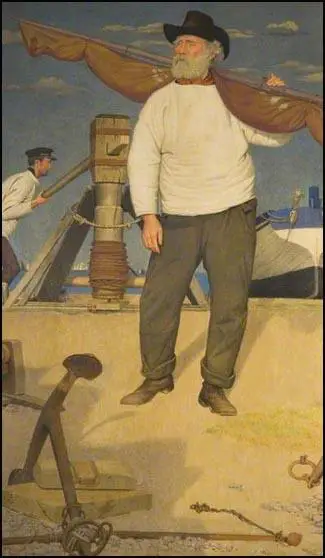

Anna frequently accompanied him on his regular visits to "Southwold, Suffolk, or Fowey, Cornwall, and to Italy or France, where Southall produced many boat studies and landscapes. In Italy he saw many examples of mural painting and was keen to promote the use of buon fresco, or true fresco, in Britain to enhance public buildings as they did in Italy." (19)

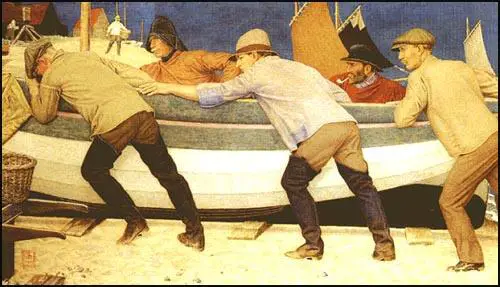

Joseph Southall regularly exhibited at the London New Gallery. The art critic at The Westminster Gazette was especially impressed with the work of Southall. "The second exhibition of the New Gallery, under its new organization, well deserves a visit…. Special attention should be given to two delightful little drawings in tempera by Mr. Joseph E. Southall. San Francesco, Assisi, is a wonderful bit of miniature work, equal to, in spirit, it in character quite apart from the work of the old illuminators of missals. In Mending the Net, Mr. Southall takes a theme from real life, and threats it with great tenderness and success, but still within the old conventions. This tiny piece of decoration is quite beautiful." (20)

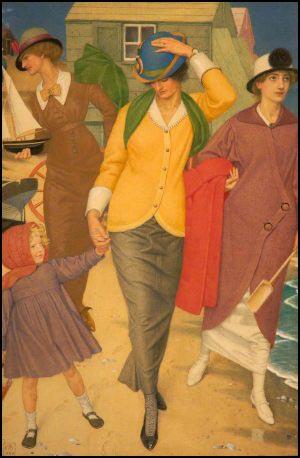

One of Southall's most popular paintings was Along the Shore (1910). His biographer, George Breeze, has claimed: "This is an extraordinary picture in many ways. There is almost a surrealistic air about its frozen nature. The ladies seem oblivious of the dangers of the salt water to their smart leather shoes. The lady nearest the sea appears to be transfixed by some vision, and contrasts with the dumpy figure of a boatman at top left, who seems amusing amid all the high seriousness, though the little girl does, it is true, manage a smile at her mother. The colouring is a veritable tour de force." (21)

Amie Berkovitch later recalled: "I was walking up the stone staircase at the entrance, in 1980, to the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and there on the wall at the top of the grand staircase hung Along the Shore by Joseph Edward Southall. I stopped dead in my tracks and gazed in wonder as people passed me by... I didn't understand why but I knew I loved this image. I bought a poster of it in the Gallery shop. I had it framed and studied it nightly.... Southall's masterpiece captures a moment in time. It is a snapshot of three Edwardian ladies walking along the sea shore, one of whom holds the hand of a little girl holding a bucket. The girl looks brightly at her guardian. Is this lady her mother? The two other women carry a spade, a toy boat, coats – friends, an aunt, the nanny perhaps? Its a blustery day; Mother holds onto her hat, her scarf caught in the wind as the sea breeze catches the blond curls of the happy little girl. The colours are vibrant yet tonally restrained, they energise without overwhelming. It is serene yet alive with movement. There in the graceful turn of a leg is the lyricism of Raphael, the dramatic foreshortening of Caravaggio as a stepping foot emerges towards us. Each character moves forward at a different angle so that the scene opens like a fan, a flower, in front of us. But as dynamic as it is, for me there has always been a frieze-like quality to the painting. There is a beautiful flatness to it, like a slice of life has been squashed between two glass plates for a microscope." (22)

In 1911 Joseph Southall painted The Agate: Portrait of the Artist and his Wife while on holiday in Southwald. Joseph wears a dark knickerbocker suit and his wife is clad in a grey-brown woollen dress offset by a black-and-white silk stole with tassels and a highly fashionable hat. "The impact of this picture is no doubt due in part to the extraordinary nature of the scene: the artist and his wife standing full length at the water's edge on a beach, in their smartest clothes, with the latter popping agate into the outstretched hand of the former, the whole frozen in time." The picture was purchased by Richard Barrow and hung in the lavatory at Barrow's Stores in Birmingham. It was so unpopular it was covered with a mirror. It was later given to the National Portrait Gallery. (23)

Joseph Southall later explained why he was so committed to this style of painting. "The great merit of true fresco lies in its deligious quality of surface which is like the bloom on a peach, and where you see as in Italy no black dirt but only a cream coloured dust accumulate upon it the effect of time is quite in harmony with the character of the work and even adds to it an additional charm." (24)

Quaker Activist

Joseph Southall was a pacifist and a member of the Liberal Party. However, he was converted to socialism after reading News from Nowhere, a novel by William Morris. (25) Southall came from a radical family. The Baker's, his mother's and his wife's family, were Quakers with strong radical sympathies. On his father's side, his grandmother was the sister of Joseph Sturge, an opponent of slavery and a strong supporter of Chartism. (26)

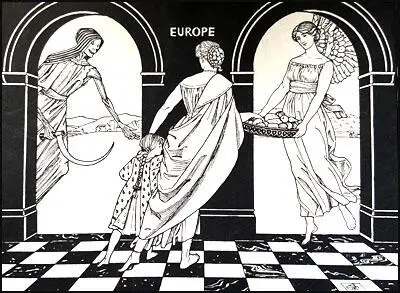

Southall carried out a series of copper engravings. "There is nothing in Southall's painting output with which to compare these allegorical figures. Peace and Labour appear to tower over their surroundings and the personification is clear: the coming of peace will bring prosperity and labour must be given its true place of dignity in the world... The engraving of Fortune is the most extraordinary of these works. Against a background of two stable pillars and standing on a geometrically regular floor, Fortune turns her wheel, which is unsupported by any visible means, while grains of sand percolate through the narrow neck of a timer." (27)

Southall was an opponent of the 1902 Education Act. The new legislation abolished all 2,568 school boards and handed over their duties to local borough or county councils. These new Local Education Authorities (LEAs) were given powers to establish new secondary and technical schools as well as developing the existing system of elementary schools. At the time more than half the elementary pupils in England and Wales. For the first time, as a result of this legislation, church schools were to receive public funds. (28)

Nonconformists and supporters of the Liberal and Labour parties campaigned against the proposed act. David Lloyd George led the campaign in the House of Commons as he resented the idea that Nonconformists contributing to the upkeep of Anglican schools. It was also argued that school boards had introduced more progressive methods of education. "The school boards are to be destroyed because they stand for enlightenment and progress." (29)

John Clifford became the leader of the campaign against the legislation. Clifford was opposed to Balfour's bill for three main reasons: (a) the rate aid was being used to support the teaching of religious views to which some rate-payers were opposed; (b) sectarian schools, supported by public funds, were not under public control; (c) teachers in sectarian schools were subject to religious tests. Clifford prepared a plan of "Passive Resistance". It was based on the strategy used by John Hampden against Ship Money in 1637 and one of the causes of the English Civil War. "Its tactics were to be those of the old Tithe War: refuse to pay the abhorrent education rate, submit rather to the forced sale of your goods and even of your house; if need be, go to jail!". (30)

Joseph and Anna Southall both became involved in the "passive resistance" campaign. (31) They "refused to pay rates as a form of objection to what they regarded as denominal religious teaching in schools. In the case of the Southalls, the goods seized regularly twice a year by police in lieu of rates were two silver tea-spoons, which were auctioned for 14s, and then returned to Mr Southall in readiness for the next rate payment to fall due." (32)

Southall often sent letters to newspapers criticising religious, business and political leaders over their views on warfare. In one letter he complained about businessmen justifying the production of armaments as being good for its employees. He argued that the "prosperity of the people of Woolwich during the war time is obtained at the cost of the whole country plunging madly into debt which generations of workers afterwards must painfully repay.... War is nothing but destruction and at best it only benefits the few at the cost of the many. What we want is not the destruction of wealth but the fair distribution of it. War never brings that – as the contractors know very well." (33)

In August 1913, Southall complained about a speech made by Thomas Mackenzie: "The High Commissioner for New Zealand insinuates in his letter that those who refuse to serve as conscripts in New Zealand are wanting in 'manliness', 'grit', or 'courage'… But who are these men? Are they not those who, believing that a Christian should love his enemy, refuse to learn how to kill him? Are they not those who, rather than disobey Christ's preaching, have defied the military authorities, suffered persecutions, and been driven away from their homes? If these men lack grit and courage, who then possess it? But one sees only too clearly why the authorities are 'glad to be rid of them'. They want the "grit" that will knuckle under to the military – the "courage" that will betray its convictions and its Master rather than suffer for them. The High Commissioner entirely fails to show any real external danger to New Zealand and her woman and children, but he does reveal a very real and terrible internal danger, the danger of falling under the cruel slavery of military tyranny. All honour to those who have faced scorn and persecution in resisting this foe of humanity." (34)

The First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War three cabinet ministers, Charles Trevelyan, John Burns and John Morley, resigned from the government. Southall also disagreed with H. H. Asquith's decision to declare war on Germany and left the Liberal Party. Southall joined the Independent Labour Party as it was the main political party opposed to the war. (35)

Joseph Southall greatly admired, Keir Hardie, the leader of the ILP and was distressed when he died on 26th September, 1915. He wrote to The Labour Leader: "May I express my profound sorrow at the loss of that great true-hearted champion of the poor – Keir Hardie. We could ill afford to lose him at any time, but especially so now." (36)

Joseph Southall also contributed drawings for the main anti-war newspaper, the Woman's Dreadnought. It was founded in January 1914 by Sylvia Pankhurst and Norah Smyth, as the newspaper of East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). Pankhurst was a strong opponent of the war. Initially, the ELFS campaigned for women's suffrage but on the outbreak of war accepted that "peace would be the overriding issue in the year to come". (37)

Southall also chaired the Birmingham Auxiliary of the Peace Society and was a joint Vice-president of the Birmingham and District Passive Resistance League. Despite his outspoken stance against the war, he was commissioned by the city to produce the fresco that stands at the head of the staircase of the entrance to Birmingham Art Gallery. (38)

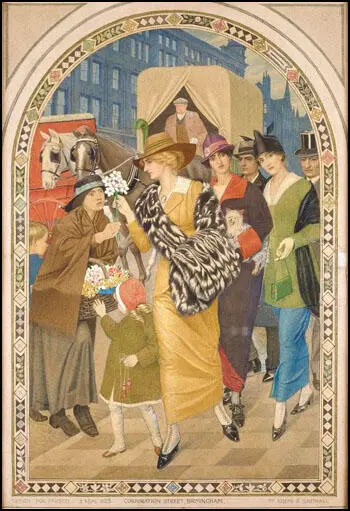

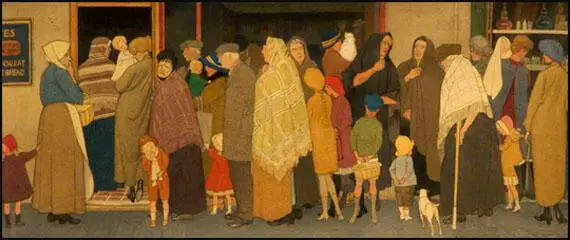

It has been argued by Richenda M. Roberts that the Corporation Street, Birmingham in March 1914 "helped to enforce notions of the divisive effects of war by suggesting that the experience of war was indeed demarcated by both geography and gender. The effect of this was that publically exhibited paintings like Southall’s fresco could be interpreted as making evident the destabilizing impact of war in a way which might be viewed as supporting the claims made by disenchanted servicemen that civilians, and particularly women, on the home front had forsaken them." (39)

One critic claims that the painting "conveys its pro-peace politics by implication, providing the population with an image of their recent pre-war community life". (40) Southall does this by placing In the foreground "a female figure clothed in a yellow-coloured dress, which is complimented by a large fur stole, has paused to purchase, from a female street vendor, a bunch of white flowers. Reaching over the curb of the pavement, which seems to cut diagonally through the centre of the fresco, dividing it into two distinct halves, the flower seller hands the female figure her purchase. The purchase of flowers, non-essential items, suggests that the female purchaser has disposable income to spend as she wishes. Moreover, the same figure’s likely wealth is enforced further by the quality and type of clothes that she is shown wearing, which, in contrast to the ‘home-made’ looking, drab, brown-coloured skirt and shawl of the flower seller." (41)

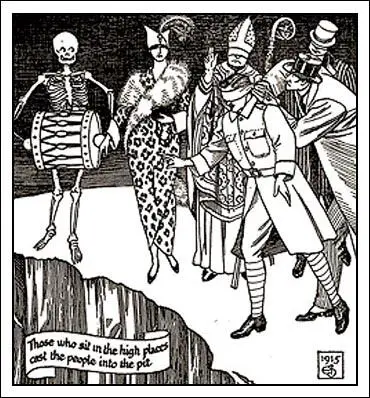

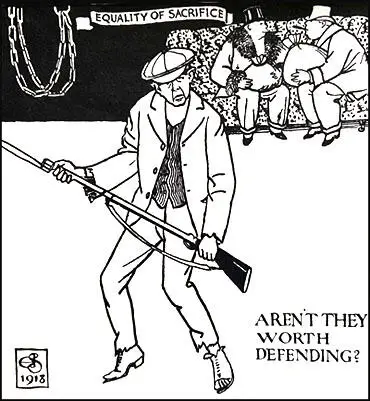

Robert L. Outhwaite, the Liberal Party MP for Hanley, was also opposed to the First World War. Outhwaite became a friends with Southall and he asked him to illustrate a pamphlet he was writing entitled The Ghosts of the Slain. It was largely allegorical in form in order to evade strict wartime censorship. The pamphlet attacked politicians and armaments manufacturers for promoting war. More controversially they criticised religious leaders who had blessed the bloodshed. "Outhwaite’s text offers a clear message of Christian pacifism, expressed in a Biblical style, which provides Southall with an ideal opportunity to articulate his own ideology." (42)

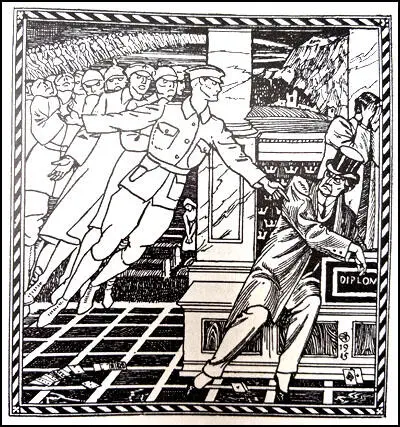

One illustration depicts "all those who sit in the high places and cast the people into the pit". A diplomat and a businessman push a blindfolded officer towards a precipice, whilst a middle-class woman looks on without complaining about what is happening. Next to her is a bishop who "blessed our banners and bade speed to our swords". Apart from Death, represented by a skeleton playing a drum, only the diplomat sees what is happening; the others all have their eyes covered. (43) In another the ghosts of the dead soldiers file in to confront the diplomats who have betrayed them by taking their country to war instead of preserving peace. (44)

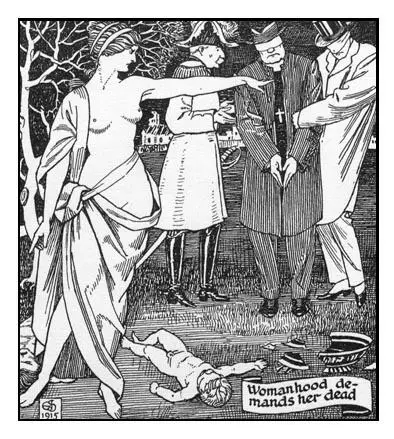

In another illustration Southall indicates "the sacrificial nature of the war, caused by promotion and perpetuation of the conflict, for which Britain's religious and secular leaders are being held accountable, to the left of the female figure in Womanhood Demands Her Dead lies the body of a young adult male figure. Drawing upon the nexus between warfare, manliness and chivalric self-sacrifice established in services recruitment campaigns, this figure can be understood as a signifier for the men who had lost their lives through being coerced by war-propaganda and peer pressure into voluntary-enlistment. Having a similar function, to the right of the female figure, laid on the ground next to a smashed china bowl, is the nude figure of a male infant whose arms form a pose implying the figure lies prostrate as a result of death." (45)

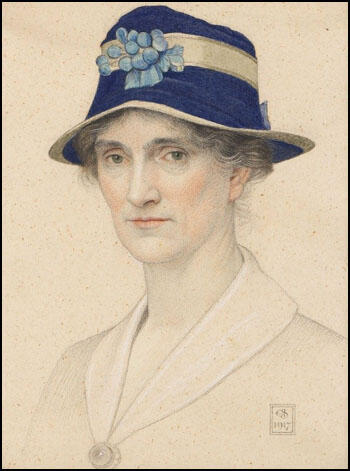

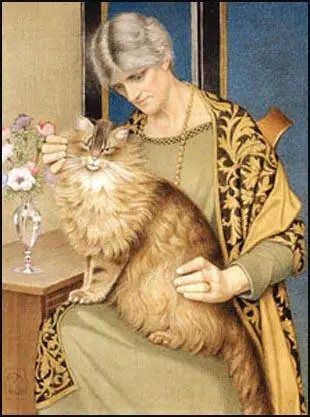

In 1917 he painted another portrait of Anna Baker Southall. According to George Breeze: "Southall's love of splendid hats comes through in this portrait, though the strong blue of this one does not overpower the delicate drawing which reveals the artist's power of characterisation." (46)

Joseph Southall also produced a pamphlet, The Friends of Peace where he stated "we wish to send a word of greeting and encouragement to those who Stand for Peace even in this dark and terrible time." (47) Southall was active in the Independent Labour Party during the war and he gave lectures on a wide variety of subjects at the Priory Rooms, in Birmingham City Centre that were publicised in The Labour Leader. This included The Yoke of Fear (48), Socialism and Peace (49) and Socialism and Art. (50)

Joseph Southall provided several free drawings for Sylvia Pankhurst's newspaper, The Woman's Dreadnought. Pankhurst was also involved in social work in the East End of London. Norah Smyth, and Henry Harben agreed to finance the establishment of the Women's Hall at 400 Old Ford Road in Bow. It was large enough to hold meetings of 350 people. It became the headquarters of the East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS). It became a social centre run largely by and for local working-class women. It housed a ‘Cost Price Restaurant' where people could get a hot meal at a very low price and free milk for their children. (51)

Southall's contact with Sylvia Pankhurst helped to change his approach to painting. This was especially true of the subject matter. This is reflected in his painting the Food Queue (1918). This scene is a complete contrast to the majority of Southall's street scenes as "there is no ladies in high fashion to give away the period" and is one of his rare examples of social realism. (52)

Roger Homan has argued: "Joseph Southall was a Quaker of deep and enduring convictions and scrupulous attention to detail... Southall takes account of these moral principles without rejecting the art in which they were thought to be inherent. On the contrary, he used his art as social critique, he rejoiced in colour as an aspect of the beauty of the created world and he undressed his portrait images of such vain trappings as had tended to cumber the genre." (53)

Final Years

After the war Joseph Southall and his wife would make regular spring and autumn visits to France and Italy. Every summer they spent time at Southwold in Suffolk. These travels invariably produced a body of work which was regularly shown in exhibitions at the "Alpine or Leicester Galleries in London and the Ruskin Galleries in Birmingham, as well as at the Royal Birmingham Society of Artists, the Royal Academy, and the Paris Salon." (54)

Southall later explained his approach to his work: "Art is a language of the soul, and who shall forbid the artist to express what is in him or limit the source of its inspiration? There remains, however, the truth that great painting and sculpture are something much more than illustration of a literary theme and that they convey something over and above the verbal narrative on which they are based ... There are pictures that are not narrative illustrations but are expressions of feelings or ideas that have no corresponding or parallel expressions in words. These are to be regarded rather as we accept instrumental music that does not attempt to tell us any story nor even to describe to us any person or thing, but awakens in our souls a sense of beauty, awe or wonder, solemnity or joy." (55)

Joseph Southall remained an active member of the Labour Party. He was also a close friend of Dr. Robert Dunstan, who was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) who was its parliamentary candidate for Birmingham West. (56) In December 1927, Southall and six other members were expelled from the party after refusing to refrain from helping him in his campaign. Southall denied that he was a Communist. "I have never been to Communist Party meetings unless they have been public and I have never subscribed to their funds." (57)

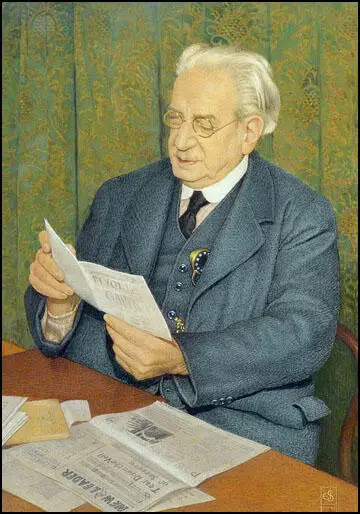

Joseph and Anne Southall made their last trip to Venice in the spring of 1937. Later that year he was taken ill and had to undergo major surgery from which he never fully recovered. His illness, although never accurately diagnosed, necessitated frequent spells in hospital for the remainder of his life. Although in pain he carried on painting. The last painting in tempera on which he was working was a memorial portrait of the Bradford MP, Frederick Jowett (1864-1944), a founder member of the Independent Labour Party. (58)

Joseph Southall died on the 6th November and was buried four days later in the Society of Friends section of Witton Cemetery. The Birmingham Post reported that at his funeral his cousin, Evelyn Sturge, spoke of his courage and "great love of truth, and of his willingness to be unpopular in the cause of truth, and of his care for the downtrodden and for justice." (59)

Southall's biographer, George Breeze, commented: "In his life Southall brought together the gathered stillness of a Quaker meeting, the jewelled calm of tempera painting, and the peace sought by pacifism." (60)

Primary Sources

(1) The Banbury Guardian (21st January 1904)

"The Place and Purpose of Art". A lecture on the above subject will be given at the Friends' Meeting House on Tuesday night by Mr. Joseph E. Southall of Birmingham. Mr Southall is an artist of the Pre-Raphaelite school, having been for a time of pupil of Burne-Jones. He is one of the greatest authorities an tempera painting in England, and is a regular exhibitor in the New Gallery. He is also a member of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society.

(2) Justice (20th April 1907)

The writer of the article in your paper on "The Necessity of War" appears to have overlooked the fact that the prosperity of the people of Woolwich during the war time is obtained at the cost of the whole country plunging madly into debt which generations of workers afterwards must painfully repay. It is like the "prosperity" of a man who pawns all the goods so that he may have a few shillings in his pockets – it cannot go on for long. War is nothing but destruction and at best it only benefits the few at the cost of the many.

What we want is not the destruction of wealth but the fair distribution of it. War never brings that – as the contractors know very well.

(3) The Westminster Gazette (7th July, 1909)

The second exhibition of the New Gallery, under its new organization, well deserves a visit…. Special attention should be given to two delightful little drawings in tempera by Mr. Joseph E. Southall. "San Francesco, Assisi", is a wonderful bit of miniature work, equal to, in spirit, it in character quite apart from the work of the old illuminators of missals. In "Mending the Net", Mr. Southall takes a theme from real life, and threats it with great tenderness and success, but still within the old conventions. This tiny piece of decoration is quite beautiful.

References

(1) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)

(2) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 5

(3) Martin Killeen, Joseph Southall and Pacifism (2021)

(4) Peyton Skipwith, Peace, Politics and Painting (January 30, 1992)

(5) The Birmingham Post (12th April, 2014)

(6) David Simkin, Family History Research (4th March, 2023)

(7) The Cambrian News (25th July 1884)

(8) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 53

(9) Roger Homan, The Art of Joseph Edward Southall (2000) page 75

(10) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 6

(11) Alan Crawford, By Hammer and Hand: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Birmingham (1984) page 66

(12) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)

(13) Joseph Southall, Grounds Suitable for Painting in Tempera (1901)

(14) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 57

(15) Joseph Southall, letter to Edward Burne-Jones (7th September, 1898)

(16) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 54

(17) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)

(18) Peyton Skipwith, Peace, Politics and Painting (January 30, 1992)

(19) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)

(20) The Westminster Gazette (7th July, 1909)

(21) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 67

(22) Amie Berkovitch, Along the Shore by Joseph Edward Southall (2017)

(23) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 55

(24) Joseph Southall, The Value of Colour in City Life (8th February, 1921)

(25) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)

(26) Justice (20th April 1907)

(27) Roy Hattersley, David Lloyd George (2010) page 148

(28) The Daily News (25th March, 1902)

(29) Frank Owen, Tempestuous Journey: Lloyd George and his Life and Times (1954) page 124

(30) The Birmingham Daily Gazette (30th October 1947)

(31) Birmingham Daily Gazette (28th February 1913)

(32) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 102

(33) The Daily Citizen (12th August 1913)

(34) Roger Homan, The Art of Joseph Edward Southall (2000) page 1

(35) The Labour Leader (7th October 1915)

(36) The Women's Dreadnought (16th December 1915)

(37) The Birmingham Post (12th April, 2014)

(38) Peyton Skipwith, Peace, Politics and Painting (January 30, 1992)

(39) Richenda M. Roberts, Art of a Second Order: The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective (2012) page 123

(40) Richenda M. Roberts, Art of a Second Order: The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective (2012) pages 145-146

(41) Robert L. Outhwaite and Joseph Southall, The Ghosts of the Slain (1915)

(42) Richenda M. Roberts, Art of a Second Order: The First World War From The British Home Front Perspective (2012) pages 213-214

(43) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 103

(44) Robert L. Outhwaite and Joseph Southall, The Ghosts of the Slain (1915)

(45) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 59

(46) Joseph Southall, The Friends of Peace (1914)

(47) The Labour Leader (28th December 1916)

(48) The Labour Leader (4th January 1917)

(49) The Labour Leader (18th October 1917)

(50) Rachel Holmes, Sylvia Pankhurst: Natural Born Rebel (2020) page 378

(51) George Breeze, Joseph Southall, 1861-1944, Artist-Craftsman (1980) page 104

(52) Roger Homan, The Art of Joseph Edward Southall (2000) page 72

(53) Peyton Skipwith, Peace, Politics and Painting (January 30, 1992)

(54) Joseph Southall, The Graphic Arts in Education (1925) page 137

(55) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain!: A New History of the Labour Party (2011) page 133

(56) The Westminster Gazette (10th December 1927)

(57) Peyton Skipwith, Peace, Politics and Painting (January 30, 1992)

(58) The Birmingham Post (11th November, 1944)

(59) George Breeze, Joseph Edward Southall: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (3rd October 2013)