On this day on 14th September

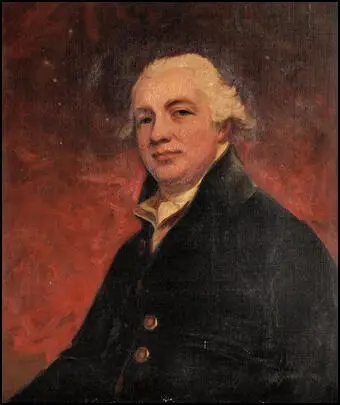

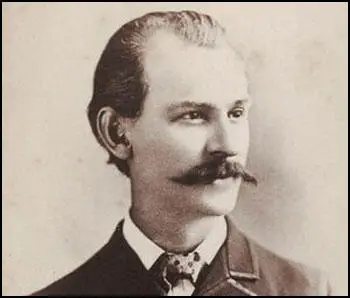

On this day in 1736 Robert Raikes, was born in Gloucester. His father was the owner of the Gloucester Journal and on his death in 1757, Robert took over the running of the newspaper. Raikes held liberal views and used his newspaper to campaign for prison reform and working class education.

In July 1780 Raikes and a local curate, Thomas Stock, decided to start a Sunday School at St. Mary le Crypt Church in Gloucester. It is claimed that Raikes got the idea when a group of rowdy children were making so much noise outside his office he could not concentrate on his work. Every Sunday the two men gave lessons in reading and writing. Raikes was not the first person to organize a school in a church but by giving it maximum publicity in the Gloucester Journal, he was able to spread his ideas to others.

The bishops of Chester and Salisbury gave support to Raikes and in 1875 a London Society for the Establishment of Sunday Schools was established. In July 1784 John Wesley recorded in his journal that Sunday Schools were "springing up everywhere". Two years later it was claimed by Samuel Glasse that there were over 200,000 children in England attending Sunday schools.

Robert Raikes retired from the Gloucester Journal in 1802. He died on 5th April 1811 and was buried in the church of St. Mary le Crypt.

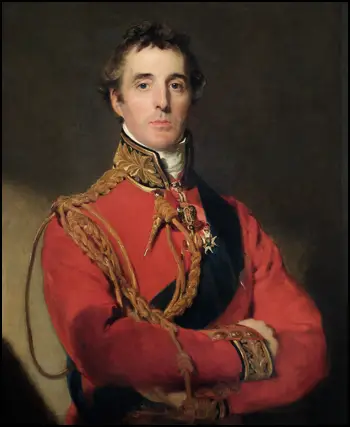

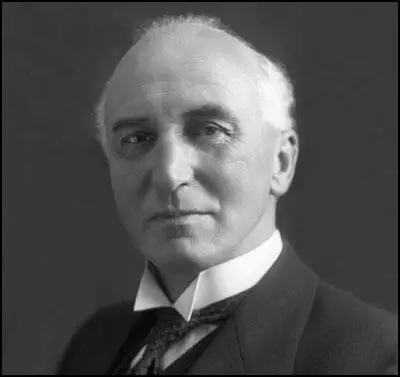

On this day in 1852 Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, died at Walmer Castle and was buried at St Paul's Cathedral on 18th November. Norman Gash claims that "the occasion for probably the most ornate and spectacular funeral ever seen in England, the procession from Horse Guards via Constitution Hill to St Paul's being witnessed, it was estimated, by a million and a half people."

Arthur Wellesley, the third surviving son of the Earl of Mornington (1735–1781), and his wife, Anne (1742–1831), was born in Dublin on 1st May 1769. According to his biographer, Norman Gash: "Arthur lost his father at the age of twelve and was thought by his imperious mother to be foolish and dull in comparison with his elder brothers, Richard Wellesley, second earl of Mornington, and William Wellesley-Pole, later Baron Maryborough and third earl of Mornington. His only talents seemed to be for playing the violin (which may have come from his father, who was an accomplished amateur musician) and arithmetical calculation. But these minor gifts were obscured by his physical indolence and social awkwardness: signs perhaps of an unhappy and lonely childhood."

In 1781 he went to Eton College where he was "an unsociable and occasionally aggressive schoolboy who made little effort to learn." Arthur was removed from the college in the summer of 1784 and joined his mother in Brussels. After receiving French lessons he was sent to the Academy of Equitation at Angers in January 1786. In addition to fencing, horsemanship, and the science of fortification, there were lessons in mathematics, grammar, and dancing.

In March 1787 a commission was obtained for Wellesley as ensign in the 73rd foot, a Highland regiment then in India. Family connections enabled him to be appointed as aide-de-camp to George Nugent-Temple-Grenville, the lord lieutenant of Ireland. In December he was commissioned as lieutenant in the 76th foot and by June 1789 had been transferred to the 12th light dragoons. The following year he became a member of the Irish House of Commons for the family borough of Trim.

In June 1791 he was commissioned as captain in the 58th foot, before moving to the 18th light dragoons in October 1792. Norman Gash has pointed out: "In little more than five years he had held commissions in six different regiments, though there is no evidence that he served with any of them. As aide-de-camp in Dublin, member of the Irish House of Commons, and manager of the family estate at Dangan, he had more than sufficient occupation. His leisure pursuits were more conventional: drinking, gambling, and getting into debt. But he still played his violin and was showing an interest in serious reading."

After being promoted to the rank of major in 1793 he proposed to Lady Catherine Sarah Dorothea Pakenham, sister of Thomas Packenham, 2nd Duke of Longford. The offer was declined by her brother on the grounds that Arthur lacked the prospect of being able to support her properly. His response to this rejection was to set fire to his violin and to give up music.

In 1794 he was assigned to an expeditionary force under Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Earl of Moira, sent out as reinforcement for Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany, in the Netherlands. During the campaign he earned an official commendation for checking a French column in a minor engagement in September 1794 at Boxte. He concluded that many of the campaign's blunders were due to the faults of the leaders and the poor organisation at headquarters. According to Richard Holmes, the author of Wellington: The Iron Duke (2002), he later recalled: "At least I learned what not to do, and that is always a valuable lesson".

In the autumn of 1795 his regiment joined an expeditionary force destined for the West Indies. However, ill-health meant the fleet sailed from Portsmouth without him. As Norman Gash points out: "This was good fortune for him, since it ran straight into a channel gale and seven transports were wrecked on Chesil Beach with great loss of life. When it was sent out again in December it was once more hit by bad weather and Wesley's ship was one of the lucky ones that found their way back to England in February 1796." In June of that year he sailed with his regiment to India.

With Napoleon gaining victories in Egypt, Wellesley was dispatched to deal with Tippoo Sahib of Mysore. At the Siege of Seringapatam in April 1799, Wellesley was ordered to lead a night attack on the village of Sultanpettah. Lewin Bentham Bowring later described what happened: "The Mysore troops took possession of the ground, and as it was absolutely necessary to expel them, two columns were detached at sunset for the purpose. The first of these, under Colonel Shawe, got possession of a ruined village, which it successfully held. The second column, under Colonel Wellesley, on advancing into the tope, was at once attacked in the darkness of night by a tremendous fire of musketry and rockets. The men, floundering about amidst the trees and the water-courses, at last broke, and fell back in disorder, some being killed and a few taken prisoners. In the confusion Colonel Wellesley was himself struck on the knee by a spent ball, and narrowly escaped falling into the hands of the enemy."

General George Harris was impressed with Wellesley efforts during the campaign and he was made administrator of the conquered territory. For the next 18 months he successfully stopped his men looting and was congratulated for persuading the soldiers to respect Indian customs. He was also able to deal with guerrilla leader Dhundia Wagh, who was defeated and killed in Hyderabad. Wellesley made himself responsible for the welfare and upbringing of Dhundia's four-year-old son, who was discovered among the enemy's baggage.

In April 1802, Wellesley was promoted to the rank of major-general. The following year he declared war on Sindhia and Berar, the two leading Maratha states, and in a surprise attack captured almost without loss the great fortress of Ahmadnagar, regarded as one of the strongest in India. He marched his troops 120 miles north-east and came into contact with whole Maratha army of some 50,000 men. Norman Gash has argued: "His force, reduced by his questionable decision to send Colonel Stevenson's Hyderabad contingent round by a different route, numbered only 7000. His men had already marched 20 miles that day and retreat would have been almost as hazardous as an advance. He took the bolder course. Guessing correctly that there must be a ford between two villages on opposite sides of the river, he crossed below the left flank of the Maratha position and placed his force in a narrow angle between the Kaitna and a tributary river, the Juah: a position which shortened his front and protected his flanks, but would have been a death-trap had he been beaten. The Marathas, under their French officers, skilfully changed front to meet him, and a desperate battle followed before victory was assured. Wellesley's right flank advanced too far and came under heavy artillery fire near Assaye village. Of approximately 5000 men who crossed the Kaitna over a third became casualties, a disproportionate number being among the British troops. Wellesley contributed by his personal example to the result. In the thick of the fighting throughout, he had one horse killed under him and another wounded."

Wellesley returned to England in 1805 and the following year he married Lady Catherine Sarah Dorothea Pakenham. In 1806 he was elected as the MP for Rye in Sussex. A year after entering the House of Commons, the Duke of Portland appointed Wellesley as his Irish Secretary. Although a member of the government, Arthur Wellesley remained in the army and in 1808 he was sent to aid the Portuguese against the French. After a victory at Vimeiro he returned to England but the following year he was asked to assume command of the British Army in the Peninsular War.

Winston Churchill argued in The Island Race (1964): "These were testing years for Wellington. He commanded Britain's sole remaining army on the continent of Europe. The French had always bent every effort to driving the British into the sea. In 1810 they were massing for a fresh attempt. In September there was a stiff battle at Busaco. The French were badly mauled and beaten." In 1812 the French were forced out of Spain and Wellesley reinforced his victory against the French at Toulouse.

In 1814 Wellesley was granted the title, the Duke of Wellington. He was then put in command of the forces which took on Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo in June, 1815. It was a savage and bloody encounter which lasted from the opening cannonade of the French guns at 11.30 a.m. until dusk fell soon after 8 p.m. That night Wellington wrote to Thomas Creevey, "It has been a damned nice thing - the nearest run thing you ever saw... ‘I never took so much trouble about any Battle and never was so near being beat".

One military historian has pointed out: "The French troops, as always, had fought with immense courage and tenacity. Now, for the first time in Wellington's experience, their morale collapsed. What started as a retreat turned into a rout.... On both sides casualties were very heavy: about 17,000 in Wellington's army, nearly 7000 among the Prussians, about 26,000 among the French, with a further 9,000 taken prisoner and up to 10,000 missing or deserted." Advancing rapidly into France, Wellington secured an armistice on 3rd July and three days later their troops entered Paris.

Wellington was disturbed by the large loss of life at Waterloo. He wrote to Lady Frances Shelley saying “I hope to God that I have fought my last battle... Next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained.” Parliament rewarded this military victory by granting Wellington the Hampshire estate of Stratfield Saye. Wellington purchased Apsley House at Hyde Park Corner. He then appointed the fashionable architect Benjamin Wyatt to "enlarge and reshape the appearance of the house to make it a fitting depository for all the war trophies, pictures, statues, and other immense and elaborate presents (mainly gold, silver, and porcelain) given to him by foreign governments and public authorities at home". In 1817 parliament rewarded Wellington for his military victory by buying the Hampshire estate of Stratfield Saye for the sum of £263,000 (£18,485,712 at 2012 prices).

Wellington developed a reputation as a womanizer. One of his mistresses, Harriette Wilson (1786–1845), tried to blackmail him by disclosing her intention to write about their relationship. Wellington famously replied: "publish and be damned". His most important relationship was with Harriet Arbuthnot (1793-1834), the wife of Charles Arbuthnot, a member of the House of Commons.

In 1818 the Duke of Wellington returned to politics when he accepted the invitation of Lord Liverpool to join his Tory administration as master-General of the Ordnance. He also served the role of general adviser to the government on all military matters. After the suicide of Lord Castereagh in 1822 Wellington took his place at the Congress of Verona. He also played a significant role in persuading George IV to appoint George Canning as the new foreign secretary.

Over the next few years Wellington clashed with Canning over foreign policy. Wellington, as someone who disliked democracy, thought it wrong to recognise the independent republics of the former Spanish and Portuguese colonies. In December 1824, he offered to resign but this was rejected by Lord Liverpool and eventually a compromise was reached.

In April 1825 Sir Francis Burdett, managed to persuade the House of Commons to pass the Catholic Relief Bill. Both the prime minister, Lord Liverpool, and the home secretary, Robert Peel, threatened to resign over this issue. Wellington worked hard behind the scenes to stop this happening. Although he also disliked Burdett's bill, he believed the time had come to settle the dispute and produced a plan of his own for legalizing and endowing the Roman church in Ireland by means of a concordat with the pope. The cabinet crisis ended in May with the defeat of Burdett's bill in the House of Lords.

Lord Liverpool had a stroke on 17th February 1827 and he was forced to resign from office. George IV interviewed Wellington, Robert Peel and George Canning for the post of prime minister. Wellington advised the king that he would not be able to serve under Canning. When the king appointed Canning, Wellington, Peel and several other leading Tories resigned from the government. Canning was forced to rely on the support of the Whigs to hold on to power. Those Whigs who accepted government posts had to promise not to raise the issue of parliamentary reform.

George Canning died on 8th August 1827 and he was replaced by Lord Goderich. Wellington now agreed to resume command of the army. Goderich's government collapsed on 8th January 1828, and Wellington agreed to form an administration. Although Wellington and the Home Secretary, Robert Peel, had always opposed Catholic Emancipation they began to reconsider their views after they received information on the possibility of an Irish rebellion. As Peel said to Wellington: "though emancipation was a great danger, civil strife was a greater danger". George IV was violently opposed to Catholic Emancipation but after Wellington threatened to resign, the king reluctantly agreed to a change in the law.

In 1830 unemployment in rural areas began to grow and the invention of the threshing machine posed another threat to the economic prosperity of the farm labourer. The summer and autumn of 1830 saw a wave of riots, rick-burnings and machine-breaking. In a debate in the House of Lords in November, Earl Grey, the Whig leader, suggested that the best way to reduce this violence was to introduce reform of the House of Commons. The Duke of Wellington replied that the existing constitution was so perfect that he could not imagine any possible alternative that would be an improvement on the present system. As Harold Wilson has pointed out: "Wellington was completely out of touch with the people, ignorant of matters of industry and trade and the vast social changes which had come about through the Industrial Revolution".

Wellington's close friend, Harriet Arbuthnot, wrote in her diary: "The Duke is greatly affected by all this state of affairs. He feels that beginning reform is beginning revolution, and therefore he must endeavour to stem the tide as long as possible, and that all he has to do is to see when and how it will be best for the country that he should resign. He thinks he cannot till he is beat in the House of Commons. He talked about this with me yesterday."

James Grant argued: "One of the greatest defects in the character of the Duke as a statesman is, his neither anticipating public opinion, nor keeping abreast with it. He generally resists it until it has acquired an overwhelming power... The Duke of Wellington is not a good speaker. His style is rough and disjointed. His manner of speaking is much worse than his diction. He has a bad screeching sort of voice, aggravated by an awkward mode of mouthing the words. His enunciation is so bad, owing in some measure to the loss of several of his teeth, that often, when at the full stretch of his voice, you do not know what particular words he is using."

In the speech on 8th November, 1830, Wellington made it clear that he had no intention of introducing parliamentary reform. Charles Greville wrote in his journal: "The Duke of Wellington made a violent and uncalled for declaration against Reform, which has without doubt sealed his fate. Never was there an act of more egregious folly, or one so universally condemned by friends and foes." When news of what Wellington had said in Parliament was reported, his home in London was attacked by a mob. Now extremely unpopular with the public, Wellington began to consider resigning from office.

Wellington's biographer, Norman Gash has argued: "The duke made his celebrated declaration, in the debate on the king's speech at the beginning of November, that the constitution needed no improvement and that he would resist any measure of parliamentary reform as long as he was in office. Couched in his usual peremptory and uncompromising style, his statement was probably intended not so much to win back the ultra-tories (the usual interpretation placed on it at the time) as to make his own attitude plain and so put a stop to all the talk of parliamentary reform which had been going on, both outside and inside the administration, for several weeks."

On 15th November, 1830 Wellington's government was defeated in a vote in the House of Commons. The new king, William IV, was more sympathetic to reform than his predecessor and two days later decided to ask Earl Grey to form a government. As soon as Grey became prime minister he formed a cabinet committee to produce a plan for parliamentary reform. Details of the proposals were announced on 3rd February 1831. The bill was passed by the Commons by a majority of 136, but despite a powerful speech by Earl Grey, the bill was defeated in the House of Lords by forty-one.

Wellington attended the opening of the Liverpool to Manchester Railway but was deeply upset by the way he was booed and hissed by the crowds as his train entered Manchester. This was a reaction to his views on the Peterloo Massacre and his opposition to the 1832 Reform Act. This experience made him hostile to the railways and he warned that cheap travel may result in revolution. However, Wellington later changed his mind about the railways after he developed a close relationship with George Hudson. Hudson helped Wellington make a great deal of money by advising him when to buy and sell railway shares.

William IV dismissed the Whigs in November 1834 and with Robert Peel absent in Italy, Wellington became temporary head of a new government until his colleague's arrival three weeks later. He then became foreign secretary. Peel immediately called a general election and during the campaign issued what became known as the Tamworth Manifesto. In his election address to his constituents in Tamworth, Peel pledged his acceptance of the 1832 Reform Act and argued for a policy of moderate reforms while preserving Britain's important traditions. The Tamworth Manifesto marked the shift from the old, repressive Toryism to a new, more enlightened Conservatism.

The general election gave Peel more supporters although there were still more Whigs than Tories in the House of Commons. Despite this, the king invited Peel to form a new administration. With the support of the Whigs, Peel's government was able to pass the Dissenters' Marriage Bill and the English Tithe Bill. However, Peel was constantly being outvoted in the House of Commons and on 8th April 1835 he resigned from office.

In August 1841 Robert Peel was once again invited to form a Conservative administration. Wellington, who was now seventy-two years old, became a minister without portfolio as well as leader of the House of Lords. Over the last few years Britain had been spending more than it was earning. Peel decided the government had to increase revenue. On 11th March, 1842, he announced the introduction of income-tax at sevenpence in the pound. He added, that he hoped that this was enable the government to reduce duties on imported goods.

Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland was severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn. Wellington disagreed with Peel over the issue he urged his cabinet colleagues in a memorandum of 30th November 1845 to support the prime minister since "a good Government for the country is more important than Corn Laws or any other consideration". The Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, but the policy split the Conservative Party and Peel was forced to resign.

The end of Peel's ministry, in June 1846, marked the effective end of the Wellington's political career. He now developed a close relationship with Angela Burdett-Coutts, one of the richest women in the world. At first he advised her on business matters. At the time she was in dispute with Edward Marjoribanks, who ran Coutts Bank. Burdett-Coutts wanted to raise the salaries of the clerks in the bank. Wellington helped her draft a letter to Marjoribanks that stated: "There are points connected with the management of my House upon which I cannot alter my opinions, founded as they are upon the invariable practice of my grandfather.... I am anxious to know whether you will consent to have prepared by next week our arrangement for a general rise in public salaries of the clerks of the House; which contrary to the practice of my grandfather has not taken place for some years."

On 19th August 1846, the Duke of Wellington wrote: "I hope you will always write to me whenever you wish to communicate with a friend." When they were apart he wrote to her daily, sometimes twice a day. It has been estimated that during the relationship Wellington sent Miss Burdett-Coutts, over 800 letters. They often sent each other the "product of their walks", a flower, a delicate leaf, a fragrant herb. Edna Healey, the author of Lady Unknown: The Life of Angela Burdett-Coutts (1978), has speculated: "Was he her lover? Undoubtedly their relationship was very close. The tone of his letters, the winding staircase to his private rooms, the intertwined locks of hair show how close it was. But it is easier to believe that she secretly married him than that she was his mistress. There is no proof of such a marriage, only persistent rumours in both their families."

Granville Leveson-Gower recorded in his diary: "The Duke of Wellington was astonishing the world by a strange intimacy he has struck up with Miss Coutts with whom he passes his life, and all sorts of reports have been rife of his intention to marry her. Such are the lamentable appearances of decay in his vigorous mind, which are the more to be regretted because he is in most enviable circumstances, without ny political responsibility, vet associated with public affairs, and surrounded with every sort of respect and consideration on every side - at Court, in Parliament, in society, and in the country."

On 7th February 1847, Angela Burdett-Coutts proposed to the Duke of Wellington, despite the age difference, he was seventy-eight and she was thirty-three. Wellington answered her in a letter the following day: "My dearest Angela, I have passed every moment of the evening and night since I quitted you in reflecting upon our conversation of yesterday, every word of which I have considered repeatedly. My first duty towards you is that of friend, guardian, protector. You are young, my dearest! You have before you the prospect of at least twenty years of enjoyment of happiness in life. I entreat you again in this way, not to throw yourself away upon a man old enough to be your grandfather, who, however strong, hearty and healthy at present, must and will certainly in time feel the consequences and infirmities of age... My last days would be embittered by the reflection that your life was uncomfortable and hopeless."

Wellington retired from public life but on 10th April 1848 he organised a military force to protect London against possible Chartist violence at the large meeting at Kennington Common. That evening Wellington wrote to Angela Burdett-Coutts: "The mobs have dispersed. There are but two or three hundred people about Palace Yard... not a shot has been fired or an individual injured - nor has a single soldier been seen."

Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington died at Walmer Castle on 14th September, 1852 and was buried at St Paul's Cathedral on 18th November. Norman Gash claims that "the occasion for probably the most ornate and spectacular funeral ever seen in England, the procession from Horse Guards via Constitution Hill to St Paul's being witnessed, it was estimated, by a million and a half people."

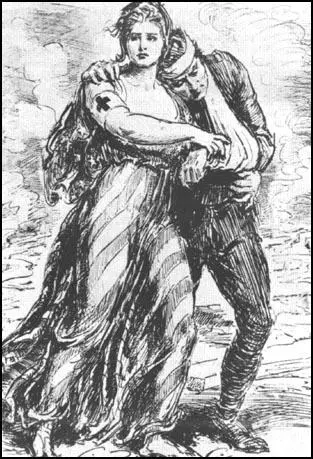

On this day in 1867 illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, the son of Charles DeWolf Gibson and Josephine Elizabeth Lovett, was born in Roxbury, Massachusetts. His great grandfather was the politician, James DeWolf.

A talented artist, he studied at the Art Students League in New York City. He sold his first drawing to Life Magazine when he was only 19. Gibson's early influences include Howard Pyle, Charles Keene and Phil May.

Gibson's illustrations also appeared in Harper's Weekly, Collier's Weekly and Scribner's Magazine. Gibson eventually obtained a full-time post with Life Magazine, where he became famous for his drawings of American high society. The young women in his drawings became known as Gibson Girls.

In 1895, he married Irene Langhorne, a sister of Nancy Astor, who later became the first woman to serve in as a Member of Parliament in the House of Commons. His wife's money enabled him to eventually become the owner and editor of Life Magazine.

Charles Dana Gibson died on 23rd December 1944.

On this day in 1879 Margaret Higgens was born in Corning, New York, on 14th September 1883. She was the sixth of eleven children. Her mother also had seven more babies that died in childhood, before dying of cervical cancer. Educated at Claverack College, she became a trained nurse and married William Sanger, an architect, in 1902. After moving to Saranac for health reasons she gave birth to three children. Over the next 12 years she devoted herself to being a housewife and mother.

In her autobiography she wrote: "My own motherhood was joyous, loving, happy. I wanted to share these joys with other women. Since the birth of my first child I had realized the importance of spacing babies, but only a few months before had I fully grasped the significant fact that a powerful law denied and prevented mothers from obtaining knowledge to properly space their families."

When her three children were old enough to go to school Margaret Sanger returned to work as a public health nurse in the slums of New York. Sanger joined the Socialist Party and became friends with other radicals such as John Reed, Upton Sinclair, Mabel Dodge, Robert Minor, Agnes Smedley, Kate Richards O'Hare, Eugene Debs, Elizabeth Flynn, Norman Thomas and Emma Goldman.

In July 1912 she was summoned to a Grand Street tenement. "My patient was a small, slight Russian Jewess, about twenty-eight years old, of the special cast of feature to which suffering lends a madonna-like expression. The cramped three-room apartment was in a sorry state of turmoil. Jake Sachs, a truck driver scarcely older than his wife, had come home to find the three children crying and her unconscious from the effects of a self-induced abortion." When Sadie Sachs died Margaret Sanger made a pledge to devote her life to making reliable contraceptive information available to women. She began her campaign by writing a column for the New York Call entitled "What Every Girl Should Know."

Upset by the poverty she experienced as a nurse in New York she founded a radical feminist magazine, The Woman Rebel. As Sanger later observed in her autobiography: "During these years in New York more and more my calls began to come from the Lower East Side, as though I were being magnetically drawn there by some force outside my control. I hated the wretchedness and hopelessness of the poor, and never experienced that satisfaction in working among them that so many noble women have found. My concern for my patients was now quite different from my earlier hospital attitude. I could see that much was wrong with them that did not appear in the physiological or medical diagnosis. A woman in childbirth was not merely a woman in childbirth. My expanded outlook included a view other background, her potentialities as a human being, the kind of children she was bearing, and what was going to happen to them."

After the death of a patient during childbirth Sanger decided to devote her life to making reliable contraceptive information available to women. She published the Birth Control Review and persuaded Lou Rogers and Cornelia Barns to be co-art editors of the journal. The main theme of her articles was that "no woman can call herself free who doesn't own and control her own body." After advice about birth-control appeared in her newspaper in 1915, she was charged with publishing an "obscene and lewd article".

The Masses gave its full support to Sanger's campaign. Floyd Dell was assistant editor at the journal: "The Masses published articles in defense of of Margaret Sanger, and the magazine was immediately flooded with thousands of letters from women, asking for information about the methods of birth control, and giving the best as well as the most heart-breaking reasons for needing such information. These letters, as associate editor, I answered, saying that we were forbidden by law to give the information; then, as a private individual, I carefully turned over all these letters to other private individuals, who mailed this information to the women; and in this law-breaking I cheerfully and conscientiously participated. I believed then, as I do now, that it is a moral duty to violate evil laws."

Margaret Sanger fled to Britain and it was while she was in London she met Marie Stopes. She later recalled: "She then explained to me that, owing to her previous unfortunate marriage she had no experience in matters of contraception nor any occasion to inform herself of their use. Could I tell her exactly what methods were used? I replied that it would give me the greatest pleasure to bring to her home such devices as I had in my possession. Accordingly, we met again the following week for dinner in her home, and inspected and discussed the French pessary which she stated she then saw for the first time. I gave her my own pamphlets, all of which contained contraceptive information."

After hearing Sanger's story Marie Stopes decided to start a birth-control campaign in Britain. She knew it would be dangerous as several people in Britain, including Richard Carlile, Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, had been sent to prison for advocating birth-control.

In December 1914 Sanger sent a letter to Havelock Ellis. As Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980), has pointed out: "He invited her to tea the following week and was startled to find her so pretty and so comparatively young. At first she was overwhelmed by his patriarchal beauty and his refusal to make small talk. She was also surprised - as many others were on first meeting him - by his thin, high voice, so unexpected in a man of his size."

Margaret Sanger fell in love with Ellis. She wrote in An Autobiography (1938): "I was at peace, and content as I had never been before... I was not excited as I went back through the heavy fog to my own dull little room. My emotion was too deep for that. I felt as though I had been exalted into a hitherto undreamed-of world."

Soon afterwards Sanger tried to turn it into a sexual relationship. Havelock Ellis wrote to her explaining "What I felt, and feel, is that by just being your natural spontaneous self you are giving me so much more than I can hope to give you. You see, I am an extremely odd, reserved, slow undemonstrative person, whom it takes years and years to know. I have two or three very dear friends who date from 20 or 25 years back (and they like me better now than they did at first) and none of recent date."

Sanger returned to New York City and on 16th October, 1916, with the help of Kitty Marion, she opened a family planning and birth control clinic in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn. It was raided nine days later by the police and Sanger served 30 days in prison. In 1917 she published What Every Mother Should Know.

Ernest Gruening, the editor of The Nation, was one of Sanger's greatest supporters and joined her campaign to distribute birth-control literature. When Patrick Hayes, the Archbishop of New York, condemned Sanger's attempts to hold a meeting in the city on the subject, he commented that "I am confident that in this great city of ours the majority of the women are too pure, clear-minded and self-respecting to want to attend or hear a discussion of such a revolting subject."

In the next edition of The Nation Gruening argued: "The Archbishop has furnished the birth control movement with advertising worth thousands of dollars. He has given all anti-clericals definite and specific evidence of clerical interference in government and hostility to the fundamental American rights of free speech which will be used in those anti-Catholic campaigns which The Nation has deplored."

Gruening invited William R. Inge, Dean of St Paul's Cathedral in London, to write an article on birth-control, which began: "The control of parenthood is perhaps the most important movement in our time. It is not only universal in the civilized world, but the degree to which it is practiced is a very fair gauge of the position of that country in the scale of civilization." Gruening added: "I continued my own activities in behalf of the birth-control movement which for the next third of a century continued to be opposed by the same forces against which Margaret Sanger had battled so indomitably."

In 1921 Sanger founded the American Birth-Control League. Later that year her friend Marie Stopes also opened the first of her birth-control clinics in Holloway on 17th March 1921. Guy Aldred and Rose Witcop, joined the campaign and when they published a pamphlet written by Margaret Sanger, they were found guilty of selling an obscene publication. The case drew much press coverage and the couple were supported financially by John Maynard Keynes, Dora Black and Bertrand Russell. Later that year this group was joined by Katharine Glasier, Susan Lawrence, Margaret Bonfield, Dorothy Jewson and H. G. Wells to establish the Workers' Birth Control Group.

Margaret Sanger continued her campaign and in 1927, Sanger helped organize the first World Population Conference in Geneva. The following year she resigned as the president of the American Birth-Control League and devoted her energies to the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau. She also published two books on the subject: Motherhood in Bondage (1928) and My Fight for Birth Control (1931).

In 1932 Margaret Sanger became president of the Birth Control International Information Center. The dissemination of birth control information by doctors was finally legalized in the United States in 1937. Her memoirs, The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger was published in 1938.

Margaret Sanger died in Tucson, Arizona, on 6th September 1966.

On this day in 1887 political activist Albert Parsons confirms in a letter to his wife, Lucy Parsons, that he is to be executed.

Our verdict this morning cheers the hearts of tyrants throughout the world, and the result will be celebrated by King Capital in its drunken feast of flowing wine from Chicago to St. Petersburg. Nevertheless, our doom to death is the handwriting on the wall, foretelling the downfall of hate, malice, hypocrisy, judicial murder, oppression, and the domination of man over his fellowman. The oppressed of earth are writhing in their legal chains. The giant Labor is awakening. The masses, aroused from their stupor, will snap their petty chains like reeds in the whirlwind.

We are all creatures of circumstance; we are what we have been made to be. This truth is becoming clearer day by day.

There was no evidence that any one of the eight doomed men knew of, or advised, or abetted the Haymarket tragedy. But what does that matter? The privileged class demands a victim, and we are offered a sacrifice to appease the hungry yells of an infuriated mob of millionaires who will be contented with nothing less than our lives. Monopoly triumphs! Labor in chains ascends the scaffold for having dared to cry out for liberty and right!

Well, my poor, dear wife, I, personally, feel sorry for you and the helpless little babes of our loins.

You I bequeath to the people, a woman of the people. I have one request to make of you: Commit no rash act to yourself when I am gone, but take up the great cause of Socialism where I am compelled to lay it down.

My children - well, their father had better die in the endeavor to secure their liberty and happiness than live contented in a society which condemns nine-tenths of its children to a life of wage slavery and poverty. Bless them; I love them unspeakably, my poor helpless little ones.

Ah, wife, living or dead, we are as one. For you my affection is everlasting. For the people. Humanity. I cry out again and again in the doomed victim's cell: Liberty! Justice! Equality!

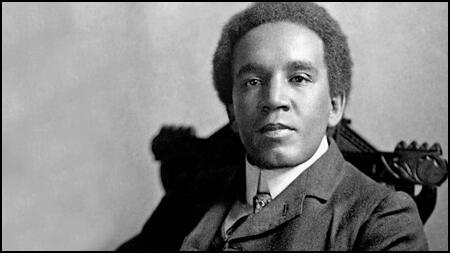

On this day in 1904 Samuel Coleridge Taylor writes a letter to Andrew Hilyer about the problem of racial prejudice in the UK.

"As for the prejudice, I am well prepared for it. Surely that which you and many others have lived in for so many years will not quite kill me. I am a great believer in my race, and I never lose an opportunity of letting my white friends here know it. Please don't make any arrangements to wrap me in cotton-wool."

On this day in 1909 Vera Wentworth justifies her assault on H. H. Asquith, according to a diary entry of Emily Blathwayt. "Vera Wentworth sent Linley (Blathwayt) a tardy acknowledgement of the photo he sent and hopes he was not shocked at their punching Asquith's head. I am writing back coldly, saying how grieved he is at the late actions and the stone throwing; telling how I was obliged to leave as I could no longer "approve the methods" and finishing "An attack on one undefended man by three women was an act I did not expect from the Society". Last time Vera and Elsie left here I promised myself they should never come again if it were only on account of the reckless destruction of other people's property.

On this day in 1939 John Simon introduces the first war budget. Henry (Chips) Channon, Conservative Party MP wrote in his diary: "The first war budget. At 3.45 Simon rose (he was directly in front of me) and in unctuous tones not unlike the Archbishop of Canterbury, opened his staggering budget. He warned the House of its impending severity yet there was a gasp when he said that Income Tax would be 7/6 in the £. The crowded House was dumbfounded, yet took it good-naturedly enough. Simon went on, and with many a deft blow practically demolished the edifice of capitalism. One felt like an Aunt Sally under his attacks (the poor old Guinness trustee, Mr Bland, could stand it no more, and I saw him leave the gallery) blow after blow; increased surtax; lower allowances; raised duties on wine, cigarettes and sugar; substantially increased death duties. It is all so bad that one can only make the best of it, and re-organise one's life accordingly."

On this day in 1944 General Bernard Montgomery orders Operation Market Garden. The combined ground and airborne attack was designed to gain crossings over the large Dutch rivers, the Mass, Waal and Neder Rijn, to aid the armoured advance of the British 2nd Army.

On 17th September 1944, three divisions of the 1st Allied Airbourne Corps landed in Holland. At the same time the British 30th Corps advanced from the Meuse-Escaut Canal. The bridges at Nijmegen and Eindhoven were taken but a German counter-attack created problems at Arnhem. Of the 9,000 Allied troops at Arnhem, only 2,400 were left when they were ordered to withdraw across the Rhine on 25th September.

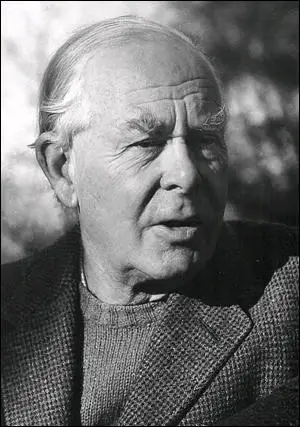

On this day in 1990 Daniel Goleman writes an appreciation of John Bowlby in the New York Times

One of the most influential forces in child psychiatry and psychology, Dr. Bowlby challenged basic tenets of psychoanalysis and pioneered methods of investigating the emotional life of children. His central focus was on what has come to be called ''attachment theory'' and the emotional impact on the child when the maternal bond is disrupted.

In arguing the case for the crucial nature of a warm, intimate and continuous relationship between mother and infant, Dr. Bowlby prompted public policy that a ''bad'' home is better for a child than a ''good'' institution. His work also inadvertently bred guilt in many working mothers, who misconstrued his message. Dr. Bowlby felt a mother's absence during the day was not a problem if there was satisfactory care in her absence.

In his major work, a three-volume exploration of the bond between the mother and child, Dr. Bowlby argued that the origins of many emotional problems in later life were a result of children's being separated as toddlers from their mothers, with no adequate substitute.

The problems such separation could lead to, he said, included depression, ''anxious attachment'' or clinginess in relationships, chronic delinquency, and pathological mourning.

''John Bowlby was a giant,'' said Dr. Albert Solnit, former director of the Child Studies Center at the Yale University Medical School. ''He was one of the most fertile, incisive thinkers about children of our century.''

''His influence is enormous and growing,'' said Elsa First, a psychoanalyst at New York University. ''Attachment theory has become more and more central over the last 10 years in psychological theory and in psychotherapy.''

Edward John Mostyn Bowlby was born Feb. 26, 1907, the son of a surgeon. He grew up in a time when many children lived with a succession of nannies, often seeing their own parents only at tea time, until they reached the age when they were sent away to boarding school.

Dr. Bowlby attended Dartmouth Royal Naval College and Trinity College, Cambridge, where he majored in natural sciences and psychology. His medical training was at University College Medical School in London. During World War II, he served in the British army as a psychiatrist.

For most of his career, from 1946 on, Dr. Bowlby was on the staff at the Tavistock Clinic and the Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. He was director of the department of child psychiatry there until 1968, and he remained as a senior research fellow and teacher after retiring in 1972. While in medical school, at the age of 22, he went into psychoanalysis with Joan Riviere, a colleague of the noted psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, who later became his supervisor for a year.

His first work in psychiatry, at the Maudsley Hospital in London, was with adults. But in the 1930's he began to focus on children, and he turned to the theme that was to dominate his life's work, the lasting emotional legacy of childhood separations and losses.

In 1950, Dr. Bowlby became a consultant to the World Health Organization, studying children who had been orphaned, institutionalized or otherwise separated from their parents. The resulting 1951 book, ''Maternal Child Care and Child Health,'' condemned the prevailing practice of hospitals and other children's institutions in depriving children there of contact with a consistent figure who could serve as a mother substitute. The failure to provide a mothering figure, he said, would leave the chlidren unable to love.

A popular version of research he did for the World Health Organization, the book, published in 1953 as ''Child Care and the Growth of Love,'' became a best seller. But Dr. Bowlby's most influential work was the the trilogy ''Attachment and Loss.'' The first volume, ''Attachment,'' was published in 1969; the second, ''Separation,'' was published in 1973, and the third, ''Loss,'' in 1980.

A re-thinking of psychoanalytic theory, ''Attachment and Loss'' saw the bond between mother and child as instinctive, like the urge to mate in adulthood. And Dr. Bowlby saw emotional problems in later life as arising from actual childhood events, like being deprived of mothering, rather than from unconscious fantasies.

In another radical break with the prevailing psychoanalytic methods and theories of his day, Dr. Bowlby turned to the study of animal behavior and to theories about how information flows between people in formulating his ideas about the mother-infant bond. Instead of relying on adult memories to reconstruct the major events of childhood, Dr. Bowlby's studies made direct observations of mothers and children.

His first volume was attacked by many leading psychoanalysts at the time, including the analyst Anna Freud, who charged him with oversimplifying and misinterpreting Freudian theory. But in recent years data supporting Dr. Bowlby's theories, and changing theories in psychoanalysis, have brought increasing importance to his work.

Productive to the end, Dr. Bowlby published ''A Secure Base,'' in 1988, published in the United States by Basic Books,) in which he explored the specifics of giving children a steady, loving home environment, and such issues as what constitutes adequate child care. ''Charles Darwin: A New Biography,'' published this year in Britain, argues that Darwin's repeated illnesses resulted from losses in childhood.

Dr. Bowlby, who was buried on the Isle of Skye, is survived by two sons, Robert and Richard, who live in London, and two daughters, Pia Duran of London, and Mary Gatling, who lives in Salisbury Wiltshire, and seven grandchildren.