On this day on 7th February

On this day in 1102 Matilda, the daughter of Henry I and Matilda of Scotland, was born at Sutton Courtenay. Henry acknowledged being the father of more than twenty bastards but was determined to have an legitimate heir. According to William of Malmesbury, Henry was very much in love with his new wife.

When she was seven-years-old, King Henry arranged for Matilda to marry the 25 year-old German king, Heinrich V. The following year she left for Germany, to be educated at the court of her betrothed in Mainz.

She was crowned in St. Peter's Basilica in 1116. "The hopes that she would become the mother of an heir to the empire were disappointed; no children survived from this marriage, though one chronicler stated not implausibly that she gave birth to one child who did not live. She proved to be a loyal and able queen consort, who carried out the onerous duties of her office with dignity".

Henry only legitimate son, William, was granted the title the Duke of Normandy and was groomed to become the next king of England. When he was ten years old, he began to attest royal documents and became the instrument of his father's diplomacy and was "trained for the succession with fond hope and immense care".

In November 1120 Henry and William returned from Normandy by boat. "Henry sailed first, having turned down the offer of a new ship - the White Ship - from Thomas Fitzstephen... followed in the new vessel. But the inebriated crew and passengers were in no fit condition for a night voyage, and the ship was rowed onto a rock outside the harbour of Barfleur. William was put into a small boat and would have escaped had he not turned back on hearing an appeal for help from his bastard sister, whereupon the boat was overloaded by others seeking safety, and sank."

Heinrich died on 23rd May, 1125. As a childless widow she had no further duties in Germany and went to live with her father in Normandy. Her biographer, Arnulf of Lisieux, claims that Matilda was "a woman who had nothing of the woman in her". Henry of Huntingdon agrees and wrote about her "masculine firmness".

After the death of Matilda's brother, William, King Henry I married Adeliza of Louvain in the hope of obtaining another male heir. Adeliza, was 18 years-old and was considered to be very beautiful, but Henry was now in his fifties and no children were born. After four years of marriage he called all his leading barons to court and forced them to swear that they would accept his daughter, Matilda, as their ruler in the event of his dying without a male heir. This included Stephen of Blois, count of Mortain. Although he had a hereditary claim to the throne through his mother, Adela, daughter of William the Conqueror, he appears to have taken the oath willingly.

Henry now decided to find a husband for Matilda to help her to rule England. He heard good reports of Geoffrey Plantagent of Anjou. According to John of Marmoutier he was "tall in stature, handsome and red-headed... he had many outstanding, praiseworthy qualities... he strove to be loved and was honourable to his friends... his words were always good-humoured and his principles admirable."

Henry began negotiations with Geoffrey's father, Foulques V d'Anjou and on 10th June 1128, the fifteen-year-old Geoffrey, who was more than eleven years her junior, was knighted in Rouen by Henry in preparation for the wedding. Geoffrey of Anjou married Matilda at Le Mans on 17th June 1128. "On his wedding day, Geoffrey of Anjou was a tall, bumptious teenager with ginger hair, a seemingly inexhaustible natural energy and a flair for showmanship."

The couple did not like each other and within a year she returned to her father at Rouen. In 1131 Henry took her to England, though Geoffrey had demanded her return. At a council held at Northampton on 8th September 1131, after the magnates had renewed their homage to her and recognized her as Henry's heir, she agreed to return to her husband. Matilda's first child, was born in Le Mans on 5th March, 1133. Henry was named after "the Anglo-Norman king whose Crown it was intended that he should inherit".

Matilda give birth to a second son, Geoffrey on 1st June, 1134. The following year her father died. Under the agreement signed in 1125, Matilda should have become Queen of England. The Normans had never had a woman leader. Norman law stated that all property and rights should be handed over to men. To the Normans this meant that her husband Geoffrey of Anjou would become their next ruler. The people of Anjou (Angevins) were considered to be barbarians by the Normans.

Most Normans were unwilling to accept an Angevin ruler and decided to help Matilda's cousin, Stephen, the son of one of the daughters of William the Conqueror, to become king. According to the author of The Deeds of King Stephen (c.1150), Stephen persuaded the people to support him by a mixture of bribes and threats. Crowned king at Westminster Abbey he was also given the title of Duke of Normandy. "Stephen shrewdly issued a charter of liberties promising to respect all the laws and customs of the realm.

Matilda reacted by establishing herself at Argentan Castle. Her third son, William, was born on 22nd July 1136. Geoffrey Plantagent led annual raids into Normandy but was unable to gain complete control of the area. The situation improved in 1138, when Matilda's half-brother, Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, renounced his allegiance to Stephen, after an attempt had been made to assassinate him.

Gilbert Foliot, the abbot of Gloucester, claims that Robert changed sides because of his reading of the Book of Numbers. "It seemed to some that by the weakness of their sex they should not to be allowed to enter into the inheritance of their father. But the Lord, when asked, promulgated a law, that everything their father possessed should pass to the daughters".

Earl Robert attacked Stephen's forces in the west of England. He then travelled to Normandy and joined Geoffrey Plantagenet in an attempt to take control of the region. This was unsuccessful and Stephen was also able to capture Robert's castles in Kent. Robert returned to England and in November, 1139, his army managed to capture Worcester from King Stephen.

Stephen was eventually captured at the Battle of Lincoln (February, 1141). Stephen had promised the people of London more self-government. This helped him gain their support in the civil war. Matilda upset them by imposing a tax on the city's citizens. When Matilda went to be crowned the first queen of England, the people rebelled and she was forced to flee from the area.

In September 1141, Robert, earl of Gloucester, was captured at the ford of Stockbridge by Flemish mercenaries under the command of William de Warenne, earl of Surrey. He was imprisoned first at Rochester, then moved back to Winchester, so as to assist the negotiations to exchange him for the king. Stephen was released on 1st November and Robert two days later.

In Normandy, Geoffrey Plantagenet, was making good progress in taking control of the region. Matilda's army was forced to retreat to Oxford where she was besieged. In December, 1141, she escaped and managed to walk the eight miles to Abingdon. Eventually, she established herself in Devizes and controlled the west of the country, whereas Stephen continued his rule from London.

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagenets (2013), has pointed out: "Stephen and Matilda both saw themselves as the lawful successor of Henry I, and set up official governments accordingly: they had their own mints, courts, systems of patronage and diplomatic machinery. But there could not be two governments. Neither could be secure or guarantee that their writ would run, hence no subject could be fully confident in the rule of law. As in any state without a single, central source of undisputed authority, violent self-help and spoliation among the magnates exploded.... Forced labour was exacted to help arm the countryside. General violence escalated as individual landholders turned to private defence of their property. The air ran dark with the smoke from burning crops and the ordinary people suffered intolerable misery at the hands of marauding foreign soldiers."

Stephen was accused of waging war on his own people. One anonymous chronicler wrote: "King Stephen set himself to lay waste that fair and delightful district, so full of good things, round Salisbury; they took and plundered everything they came upon, set fire to houses and churches, and, what was a more cruel and brutal sight, fired the crops that had been reaped and stacked all over the fields, consumed and brought to nothing everything edible they found. They raged with this bestial cruelty especially round Marlborough, they showed it very terribly round Devizes, and they had in mind to do the same to their adversaries all over England".

A. L. Morton has argued that the civil war brought out the "worst tendencies of feudalism" and during this period "private wars and private castles sprang up everywhere" and "hundreds of local tyrants massacred, tortured and plundered the unfortunate peasantry and choas reigned everywhere". Morton claims that this "taste of the evils of unrestrained feudal anarchy was sharp enough to make the masses welcome a renewed attempt of the crown to diminish the power of the nobles."

In 1147, Geoffrey and Matilda's, fourteen-year-old son, Henry arrived in England with a small band of mercenaries. His mother disapproved of this escapade and refused to help. So also did Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester, who was in charge of Matilda's forces: "So with the impudence of youth he applied to the man against whom he was fighting and with characteristic generorosity Stephen sent him enough money to pay off his mercenaries and go home."

The Deeds of King Stephen reports that "Matilda, Countess of Anjou, who was always above feminine softness and had a mind steeled and unbroken in adversity.... She began to assume the loftiest haughtiness of the greatest arrogance - not now the humble gait of feminine docility, but she began to walk and talk more severely and more arrogantly than was customary, and to do everything herself. " Lisa Hilton, the author of Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens (2008) has pointed out that "these traits... would not have been so greatly criticized had they been displayed by a man."

The following year Matilda decided to abandon her campaign to gain control of England. She had been unable to unite the barons behind her. William of Newburgh blamed it on her "intolerable feminine arrogance". Her biographer, Marjorie Chibnall, suggested that she did indeed lack certain leadership qualities: "Matilda had shown on the height of her power that she had neither the political judgement nor the understanding of men to enable her to act wisely in a crisis."

Matilda returned to Normandy which was now under the control of her husband, Geoffrey Plantagent. She lived in the priory of Notre-Dame-du-Pré. Over the next few years Matilda was able to combine active involvement in the business of the duchy with a semi-religious retreat. She also helped to finance the building of a new stone bridge over the Seine, linking Rouen with the royal park at Quevilly and the priory of Le Pré.

Matilda's plan was that as soon as Henry was old enough, Geoffrey would abdicate as Duke of Normany and the title would go to her son. However, this plan was not put into operation as Geoffrey died on 7th September 1151. According to John of Marmoutier, Geoffrey was returning from a royal council when he was stricken with fever. He was buried at St. Julien Cathedral in Le Mans.

In January 1153, Henry, now aged 20, surprised Stephen by crossing the channel in midwinter. The two leaders made a series of truces which were turned into a permanent peace when the death of Eustace, in August, persuaded the king to give up the struggle. (33) In December, 1153, Stephen signed the Treaty of Winchester, that stated he was allowed to keep the kingdom on condition that he adopt Henry as his son and heir.

Stephen died in October 1154, and Henry became king. He took over without difficulty and it was the first undisputed succession to the throne since William the Conqueror took power in 1066. Henry II was the most powerful ruler in Western Europe with an empire which "stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees... but it is important to remember that although England provided him with great wealth as well as a royal title, the heart of the empire lay elsewhere, in Anjou, the land of his fathers."

In 1160 Queen Matilda suffered a serious illness, but after her recovery she remained active in government until she died on 10th September 1167.

On this day in 1478, Thomas More, the eldest of three sons and second of seven children of Sir John More and his first wife, Agnes Graunger More, was born in London. His grandfather, William More, was a wealthy baker and his father was a barrister who was later knighted and served as a judge of the king's bench.

More was sent to study Latin at St Anthony's School in Threadneedle Street. It was considered to be London's finest grammar school. In 1489 he became a page in the household of John Morton, Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England.

Jasper Ridley, the author of The Statesman and the Fanatic (1982) has pointed out: "The practice of placing young boys as pages in great households had survived from the age of feudal chivalry; and to be a page in Moreton's household was a splendid opportunity which Thomas did not waste. He waited on Morton at the dinner table, and acted in plays in the household during the Twelve Days of Christmas. The Archbishop supervised his education, and introduced him to a circle of acquaintances whose level of culture was very different from that of John More's legal and commercial friends in the City of London."

Morton was impressed with More's intelligence and arranged for him to attend Canterbury College. At Oxford University he studied Greek, which was then unusual, and was thought to show a sympathy with "Italian infidels". The authorities and his father objected, and he was removed from the university and he returned to London. More was now "attracted to the Carthusians, practised extreme austerities, and contemplated joining the order."

More's father was a lawyer, and he decided to follow the same profession. More was admitted on 12th February 1496 to Lincoln's Inn, where he remained for the next five years. More came under the influence of the ideas being promoted by Desiderius Erasmus, John Colet, Thomas Linacre, and William Grocyn. "With them the humanist movement in England - the study of man and his relationship to God - came of age."

In 1499 Erasmus made his first visit to England where he resumed his friendship with Colet, who introduced him to More. John Guy agues that Erasmus had a great influence over More, Cuthbert Tunstall and Richard Pace. However, "Erasmus aspired to 'peace of mind' and 'moderate reform' through the application and development of critical insight and the power of humane letters. He eschewed politics; some said he was a dreamer. Colet, More, Tunstall, and Pace, by contrast, became councillors to Henry VIII: they resolved to enter politics and Erasmus disapproved, predicting the misfortunes that befell those who put their trust in princes."

Religious "humanists" advocated the study of classical history and literature. They were especially influenced by the works of Cicero who expressed his belief in the value of the human individual. "He argued that individuals should be autonomous, free to think for themselves and possessed of rights that define their responsibilities; and that all men are brothers... The endowment of reason confers on people a duty to develop themselves fully, he said, and to treat one another with generosity and respect." The established Church was highly suspicious of humanism as it "threatened to liberate minds" and made attempts to suppress the movement.

In 1504 John More became a member of the House of Commons, and became a leading critic of Henry VII. He was opposed to the king's new taxes and when this campaign was successful, the king was furious and sent him to the Tower of London, releasing him only on the payment of £100. However, he later became a supporter of Henry VIII and after being knighted and was employed by the king as a diplomat.

In January 1505, More married Jane Colt. The couple established a home at the Old Barge, Bucklersbury. Their first daughter, Margaret was born later that year, followed by two more daughters, Elizabeth (1506) and Cicely (1507), and a son, John (1509). More held strong views on education, as he explained to William Gonell, a man who he employed as a tutor to his children: "I have warned my children to avoid the precipices of pride and haughtiness, and to walk in the pleasant meadows of modesty; not to be dazzled at the sight of gold; not to lament that they do not possess what they erroneously admire in others; not to think more of themselves for gaudy trappings, nor less for the want of them, neither to deform the beauty that nature has given them by neglect, nor to try to heighten it by artifice, to put virtue in the first place, learning in the second; and in their studies to esteem most whatever may teach them piety towards God, charity to all, and Christian humility in themselves. By such means they will receive from God the reward of an innocent life, and the assured expectation of it, will view death without horror, and meanwhile possessing solid joy, will neither be puffed up by the empty praise of men, nor dejected by evil tongues. These I consider the genuine fruits of learning.

As Alison Plowden, the author of Tudor Women (2002) has pointed out that More and his humanist friends were all deeply interested in education and anxious to propagate their plans for a wider and more liberal curriculum in the schools and universities. "More was the first Englishman seriously to experiment with the novel idea that girls should be educated too. This may have been partly due to the fact that he had three daughters and an adopted daughter but only one son, and was undoubtedly helped by the fact that the eldest girl, Margaret, turned out to be unusually intelligent and receptive. She and her sisters Elizabeth and Cecily, together and their foster-sister Margaret Gigs, studied Latin and Greek, logic, philosophy and theology, mathematics and astronomy, and Margaret More, who presently became Margaret Roper, developed into a considerable and widely respected scholar in her own right."

More explained: "Nor do I think the harvest will be much affected whether it is a man or a woman who sows the field. They both have the same human nature, which reason differentiates from that of beasts; both, therefore, are equally suited for these studies by which reason is cultivated, and becomes fruitful like a ploughed land on which seed of good lessons has been sown. If it be true that the soil of woman's brain be bad, and apter (appropriate) to bear bracken than corn, by which saying many keep women from study. I think, on the contrary, that a woman's wit is on that account all the more diligently to be cultivated, that nature's defect may be reduced by industry." He then went on to give the example of early Christians such as Augustine of Hippo who not only "exhorted excellent matrons and most noble virgins to study, but in order to assist them, diligently explained the abstruse meanings of Holy Scripture, and wrote for tender girls letters replete with no much erudition, that now-a-days old men, who call themselves professors of sacred science, can scarcely read them correctly, much less understand them."

The notion that women could be equal to men would have been been totally foreign to the Tudor upper classes. A woman, single or married, possessed very few legal rights. A woman's body and her worldly goods both became her husband's property on marriage, and the large allowed him to do exactly as he pleased with them. As Alison Weir has pointed out: "The concept of female education gradually became accepted and even applauded... The education of girls was the privilege of the royal and the rich, and its chief aim was to produce future wives schooled in godly and moral precepts. It was not intended to promote independent thinking; indeed, it tended to the opposite."

Thomas More was appointed Justice of the Peace for Middlesex in 1509, and later that represented Westminster in the House of Commons. The following year he was appointed one of two under-sheriffs for the City of London in 1510. In the summer of 1511 More's wife, Jane, died, and within a month he married Alice Middleton, the widow of John Middleton, a wealthy London merchant. She brought a daughter, Alice, into the More household. "More later wrote that he could not tell which was dearer to him, the wife who bore their children or the wife who raised them, although privately he intimated that his second wife was less intellectually capable than his first."

In 1515 Thomas More had a meeting with his good friend, Pieter Gillis, secretary to the city of Antwerp, and discussed the content of a novel he was writing called Utopia ("Utopia" is Greek for "nowhere"). The following year he sent the novel to Gillis: "I am almost ashamed, my dear Peter Giles, to send you this little book about the state of Utopia after almost a year, when I am sure you looked for it within a month and a half. Certainly you know that I was relieved of all the labour of gathering materials for the work and that I that I had to give no thought at all to their arrangement."

More's book had been influenced by the writings of Plato, especially his book, The Republic (c. 375 BC). In the book he attempts to describe the ideal society. "Plato proposes a thoroughgoing communism... The guardians are to have small houses and simple food; they are to live as in a camp, dining together in companies; they are to have no private property beyond what is absolutely necessary. Gold and silver are to be forbidden. Though not rich, there is no reason why they should not be happy; but the purpose of the city is the good of the whole, not the happiness of one class. Both wealth and poverty are harmful, and in Plato's city neither will exist."

Plato applies his communism to the family. Friends, he says, should have all things in common, including women and children. He admits that this presents difficulties, but thinks them not insuperable. One way of dealing with this problem is for women to have complete equality with men. For example, all girls are to have exactly the same education as boys, learning music, gymnastics, and the art of war along with the boys. "The same education which makes a man a good guardian will make a woman a good guardian; for their original nature is the same."

The book tells of a seaman who has discovered an island called Utopia. The work begins with written correspondence between Thomas More and several people he had met on the continent. He used the names of real people to increase the plausibility of his fictional land that is located in the southern hemisphere. "The island of Utopia is in the middle two hundred miles broad, and holds almost at the same breadth over a great part of it, but it grows narrower towards both ends. Its figure is not unlike a crescent. Between its horns the sea comes in eleven miles broad, and spreads itself into a great bay, which is environed with land to the compass of about five hundred miles, and is well secured from winds. In this bay there is no great current; the whole coast is, as it were, one continued harbour, which gives all that live in the island great convenience for mutual commerce. But the entry into the bay, occasioned by rocks on the one hand and shallows on the other, is very dangerous. In the middle of it there is one single rock which appears above water, and may, therefore, easily be avoided; and on the top of it there is a tower, in which a garrison is kept; the other rocks lie under water, and are very dangerous. The channel is known only to the natives; so that if any stranger should enter into the bay without one of their pilots he would run great danger of shipwreck."

More tells the reader he was told about Utopia by a traveller Raphael Hythlodaeus (Greek for "expert in nonsense"), whom he met in Belgium. The people on this island live in a completely different way from the people of Tudor England. In his book people elect their government annually by secret ballot; wear the same kind of clothes and only work for six hours a day. There is no money or private property on the island. Free education and health care is available for all. All goods are stored in large storehouses. People take what they want from the storehouses without payment. Hythlodaeus explains that for the people of the island "the end is the pursuit of virtue for its own sake". Public service is the noblest of callings and that "everyone takes delight in individual and collective virtue the state is at peace externally and internally".

Thomas More explains: "When Raphael Hythloday had thus made an end of speaking, though many things occurred to me, both concerning the manners and laws of the people, that seemed very absurd, as well as their way of making war, as in their notions of religion and divine matters, together with several other particulars, but chiefly what seemed the foundations of all the rest, their living in common, without the use of money, by which all nobility, magnificence, splendor, and majesty, which, according to the common opinion, are the true ornaments of a nation, would be quite taken away."

As Bertrand Russell has argued, Utopia was very different from the society that More lived in: "Everybody - men and women alike - works six hours a day, three before dinner and three after. All go to bed at eight, and sleep eight hours. In the early morning there are lectures, to which multitudes go, although they are not compulsory. After supper an hour is devoted to play. Six hours' work is enough, because there are no idlers and there is no useless work; with us, it is said, women, priests, rich people, servants, and beggars, mostly do nothing useful, and owing to the existence of the rich much labour is spent in producing unnecessary luxuries; all this is avoided in Utopia. Sometimes it is found that there is a surplus, and the magistrates proclaim a shorter working day for a time... The government is a representative democracy, with a system of indirect election."

More seemed to approve of Utopia: "I have described for you as accurately as I can the structure of the commonwealth of Utopia, which I believe to be the only the best social order in the world, but the only one that can properly claim to be literally a commonwealth. Everywhere else people talk about the public good but pay attention to their own private interests. In Utopia, where there is no private property, everyone is seriously concerned with pursuing the public welfare. Both here and there people act with good reason, for the outside Utopia there can't be anyone who doesn't realize that unless they take care of their own welfare they may die of hunger, no matter how much the commonwealth prospers."

People living in Utopia had unusual marriage arrangements: "As for marriage, both men and women are sharply punished if not virgin when they marry; and the householder of any house in which misconduct has occurred is liable to incur infamy for carelessness. Before marriage, bride and groom see each other naked; no one would buy a horse without first taking off the saddle and bridle, and similar considerations should apply in marriage. There is divorce for adultery or 'intolerable waywardness' of either party, but the guilty party cannot remarry. Sometimes divorce is granted solely because both parties desire it.

One of the main differences between England and Utopia concerned religious tolerance: "There are several sorts of religions, not only in different parts of the island, but even in every town; some worshipping the sun, others the moon or one of the planets. Some worship such men as have been eminent in former times for virtue or glory, not only as ordinary deities, but as the supreme god... And, indeed, though they differ concerning other things, yet all agree in this: that they think there is one Supreme Being that made and governs the world, whom they call, in the language of their country, Mithras . They differ in this: that one thinks the god whom he worships is this Supreme Being, and another thinks that his idol is that god; but they all agree in one principle, that whoever is this Supreme Being, He is also that great essence to whose glory and majesty all honours are ascribed by the consent of all nations."

The important point was that despite having different religions, all of them were tolerated. "Almost all believe in God and immortality; the few who do not are not accounted citizens, and have no part in political life, but are otherwise unmolested.... Women can be priests, if they are old and widowed. The priests are few; they have honour, but no power... Raphael Hythloday relates that he preached Christianity to the Utopians, and that many were converted when they learnt that Christ was opposed to private property. The importance of communism is constantly stressed."

Some people claimed that in the book More was describing his vision of what England should be like. Others claimed that More had written a book that was supposed to make people laugh because he thought it was a ridiculous idea. More's biographer, Raymond Wilson Chambers, pointed out the irony of the fact that the word "Utopia" has come to mean an ideal society which is incapable of realisation, whereas More's Utopia is "a sternly righteous and puritanical State where few of us would feel quite happy" but has many features which have been applied in practice in the twentieth century.

Jasper Ridley has argued: "More's Utopia was exactly what the word has come to mean today. He knew that it was not practicable to introduce such a system into the Europe of 1516, but he believed that it was the perfect society - or rather, that it was the kind of society which pure reason would lead him to believe was the perfect society if pure reason was the only factor involved, which he knew was not the case." Anthony Grayling takes a different view: "More himself ends on a note of doubt about such a complete system of communism... He does not end by endorsing this latter view outright; he says he would himself like to see in his own country many of the things Hythloday describes; but he leaves open which things he would not like to see."

More wrote Utopia in Latin, as he intended it to be read by the intellectuals of Europe, not by the common people. (It was not translated into English for another 35 years.) When it was published it was "acclaimed by scholars throughout Christendom". According to More, some readers took it so seriously that they believed that the island of Utopia really existed, and one of them suggested to More that missionaries should be sent to convert the Utopians to Christianity.

Lacey Baldwin Smith, the author of Treason in Tudor England (2006) has argued that More lacked empathy. In his book Smith discusses More's reaction to the May Day Riots of 1517. Smith argues that modern historians explain the disturbances on domestic economic distress caused by fast rising prices. However, More blames it on agents provocateurs and conspirators. "Once the Reformation broke out, conspiracy took on more sinister and far more cosmic proportions, but nevertheless the conviction prevailed that heresy and its uglier stepsister sedition were the product of tiny groups of conspiring individuals determined upon private profit. Despite the extraordinary speed with which Protestant ideas spread and their obvious association with the basic economic, political and psychological needs of the century, More... continued to view the religious upheaval as the work of a handful of evil men and women set upon corrupting innocent but, alas, gullible subjects."

Henry VIII was impressed by Thomas More and by 1518 "More acted in effect as the King's secretary". It is claimed by his biographer, Nicholas Harpsfield, that More was reluctant to join the government. In July 1519, Desiderius Erasmus described his friend, Thomas More, to Ulrich von Hutten. "He is not tall, without being noticeably short … his complexion tends to be warm rather than pale … with eyes rather greyish-blue, with a kind of fleck in them, the sort that usually indicates a gifted intelligence… His expression shows the sort of man he is, always friendly and cheerful, with something of the air of one who smiles easily, and… disposed to be merry rather than serious or solemn, but without a hint of the fool or the buffoon."

In 1520 the doctrines of Martin Luther were deemed to be heretical and his books were banned. The following year, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, in a great ceremony burned Luther's texts on a pyre set up in St Paul's Churchyard. It was already too late to staunch the flow of the new doctrines. Thomas More complained that the heretics were "busily" at work in every alehouse and tavern, where they expounded their doctrines. More had pointed out that he had seen young lawyers were "wont to resort to their readings in a chamber at midnight".

Wolsey was pleased by the support he received from More and this led to a series of important posts such as Treasurer of the Exchequer (1521) and Chancellor of Lancaster (1525). He also served as Speaker of the House of Commons and sent on foreign missions to France, Spain and Italy. "More assumed the position of sole royal secretary until 1526 and several times afterwards - largely because during these years of political upheaval Wolsey felt he could trust no one else. Despite acting as an intermediary between the lord chancellor and the king, More was among the most active participants in council meetings and dealt with the full range of councilor activity."

In 1527 More was painted by Hans Holbein. It has been argued by the art historian, Helen Langdon: "Holbein presents the public figure, robed in authority (for all his saintly reputation More was ferocious enough to condemn heretics to be burnt.) The determined severity of countenance betrays little of the retiring scholar, although this is suggested in the figure's slight sloop. More was certainly concerned with the impression he made, insisting on having the flamboyant cuffs on his official costume replaced by ascetic plain ones."

After reading More's book people might have thought that he would be in favour of religious toleration. However, since More had written Utopia there had been a rapid growth in Protestantism. More was a strong supporter of the Catholic Church and he was determined to destroy the Protestant movement in England. In March 1528, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall decided to commission More to mount an attack on those heretics producing religious books in English. Tunstall explained to More that heretics were "translating into our mother tongue some of the vilest of their booklets and printing them in great numbers" and by these means they were "striving with all their might to stain and infect this country."

In 1528 Simon Fish published A Supplication for the Beggars. It was only 5,000 words long and took up only fourteen small pages and was written by a "layman for layman". It could be read in an hour and was easy to conceal as it was not published legally. It was also cheap enough to distribute free of charge. "The language was straightforward too, addressing laymen's issues in laymen's words." Fish argued that the clergy should spend their money in the relief of the poor and not amass it for monks to pray for souls. Fish claimed that monks were "ravenous wolves" who had "debauched 100,000 women". He added that the monks were "the great scab" that would not allow the Bible to be published in "your mother tongue".

J. S. W. Helt has pointed out: "This short and violently anti-clerical tract challenged the existence of purgatory and presented cruel and wildly exaggerated accounts of clerical abuses done in the name of the souls, and in doing so introduced new strategies for controversial debate into the early stages of the English Reformation." It has been claimed by John Foxe that Anne Boleyn presented a copy of the book to Henry VIII who "kept the book in his bosom for three or four days" and who then embraced Fish "with a loving countenance" when he "appeared at court, took him hunting for several hours, and gave him a signet ring to protect him from his enemies".

George M. Trevelyan has suggested that this work had an impact on the thinking of the King: "The conclusion reached by the pamphleteer (Simon Fish) is that the clergy, especially the monks and friars, should be deprived of their wealth for the benefit of the King and Kingdom, and made to work like other men; let them also be allowed to marry and so be induced to leave other people's wives alone. Such crude appeals to lay cupidity, and such veritable coarse anger at real abuses uncorrected down the centuries, had been generally prevalent in London under Wolsey's regime, and at his fall such talk became equally fashionable at Court."

In March 1528, Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall decided to commission Thomas More to mount a counter-attack. Tunstall explained to More that religious reformers were "translating into our mother tongue some of the vilest of their booklets and printing them in great numbers" and were "striving with all their might to stain and infect this country". Tunstall licensed More to possess and read heretical books, blessed him and sent him forth into battle "to aid the Church of God by your championship."

Thomas More published his reply to Simon Fish in October 1529. His Supplication of Souls was more than ten times the length of A Supplication for the Beggars. Most people agree that " its point-by-point rebuttal, of a kind appropriate to learned debate, although movingly written, failed to attain the rhetorical power of Fish's more populist tract". Fish now came under attack from Archbishop William Warham who charged him with heresy.

More wrote to a friend that he especially hated the Anabaptists: "The past centuries have not seen anything more monstrous than the Anabaptists". His biographer, Jasper Ridley, has argued: "As Thomas More approached the age of fifty, all the conflicting trends in his strange character blended into one, and produced the savage persecutor of heretics who devoted his life to the destruction of Lutheranism. To say that he suffered from paranoia on this subject would be to resort to a glib phrase, not a serious psychiatric analysis; but it is unquestionable that More, like other persecutors throughout history, believed that the foundations of civilisation, and all that he valued as sacred, were threatened by the forces of evil, and that it was his mission to exterminate the enemy by all means, including torture and lies. The worst of all the heretics were the Anabaptists, the most extreme of all the Protestant sects, who were already causing great concern to the authorities in Germany and the Netherlands. They not only rejected infant baptism, but believed, like the inhabitants of Utopia, that goods should be held in common."

Thomas More wrote that of all the heretical books published in England, Tyndale's translation of the New Testament, was the most dangerous. He began his book, Confutation of Tyndale's Answer, with a striking opening sentence: "Our Lord send us now some years as plenteous of good corn we have had some years of late plenteous of evil books. For they have grown so fast and sprung up so thick, full of pestilent errors and pernicious heresies, that they have infected and killed I fear me more simple souls than the famine of the dear years have destroyed bodies."

On this day in 1812 Charles Dickens, the son of John Dickens and Elizabeth Dickens, was born at 13 Mile End Terrace (now 393 Old Commercial Road), Landport, just outside the old town of Portsmouth, on 7th February 1812.

John Dickens was the son of William Dickens and Elizabeth Ball Dickens. His parents were servants in the household of John Crewe, a large landowner in Cheshire with a house in Mayfair. William Dickens, recently promoted to the post of butler, died just before his son was born. His mother continued to work as a servant at Crewe Hall.

John Crewe was the member of the House of Commons for Cheshire. His wife, Frances Crewe was a leading supporter of the Whig Party and regular visitors to Crewe Hall included leading politicians such as, Charles James Fox, Augustus FitzRoy and Edmund Burke. They also hosted artists and writers such as Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Charles Burney, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Sarah Burney and Hester Thrale. During this period Frances became the mistress of Sheridan, the country's leading playwright. He had dedicated his most famous play, The School for Scandal, to her in 1777.

John Dickens was treated very well by the Crewe family. He was allowed to use the family library and in April 1805 was appointed to the Navy Pay Office in London. The Treasurer of the Navy at this time was George Canning, a close friend of the Crewe family. The job came to Dickens through Canning's patronage, on which all such appointments depended. Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "John Dickens may have been the son of the elderly butler, but it is also possible that he had a different father - perhaps John Crewe, exercising his droit de seigneur, cheering himself up for his wife's infidelities, or another of the gentlemen who were regular guests at the Crewe residences. Or he may have believed that he was. His silence about his first twenty years, his habit of spending and borrowing and enjoying good things as though he were somehow entitled to do so, all suggest something of the kind, and harks back to the sort of behaviour he would have observed with dazzled eyes at Crewe Hall and in Mayfair."

Charles Dickens's mother was the daughter of Charles Barrow, who worked as Chief Conductor of Monies at Somerset House in London. According to her friends she was a slim, energetic young woman who loved dancing. She had received a good education and appreciated music and books. Elizabeth had several brothers. John Barrow was a published novelist and poet, whereas Edward Barrow was a journalist who married an artist. A third brother, Thomas Barrow, worked in the Navy Pay Office, where he met fellow worker, John Dickens. Elizabeth married Dickens at St Mary-le-Strand in June, 1809. The following year her father, Charles Barrow, was forced to leave the country, when it was discovered that he had been defrauding the government. A daughter, Fanny Dickens, was born was born in August 1810.

Charles Dickens later argued that his mother was an amazing woman: "She possessed an extraordinary sense of the ludicrous, and her power of imitation was something quite astonishing. On entering a room she almost unconsciously took an inventory of its contents and if anything happened to strike her as out of place or ridiculous, she would afterwards describe it in the quaintest possible manner." R. Shelton MacKenzie, the author of Life of Charles Dickens (1870) commented: "Elizabeth Dickens... was tall and thin, with a wasp's waist, of which she was very vain... She was a good wife, very fond of her husband and devoted to her children... She has been described to me as having much resembled Mrs. Nickleby... in the charming inaccuracy of her memory and the curious insecutiveness of her conversation."

John Dickens continued to make progress at the Navy Pay Office. In 1809 he was promoted and given a salary of £110 a year. He almost certainly got this post because Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the Treasurer of the Navy, had been a supporter of his career. It has been speculated that Sheridan, the country's leading playwright, could have been Dickens's father.

Dickens was transferred to London and the family found lodgings in Cleveland Street. Dickens was now earning £200 a year. However, he always had trouble managing money. He liked to dress well, enjoyed entertaining friends and bought expensive books. Dickens was soon in debt and had to ask for loans from family and friends.

In April 1816, a fourth child, Letitia, was born. Seven months later John Dickens was sent by the Navy Pay Office to work at Chatham Dockyard. Dickens rented a house at 11 Ordnance Terrace. Charles Dickens remembers his father taking him aboard the old Navy yacht Chatham and sailing up the Medway to Sheerness, where he had to distribute wages to the workers. It has been claimed that "this landscape and the sludge-coloured tidal rivers haunted him and became part of the fabric of his late novels".

The salary of John Dickens continued to grow and by 1818 he was earning over £350 a year. He still could not manage and in 1819 he borrowed £200 from his brother-in-law, Thomas Barrow. When he did not pay the money back, Thomas told him that he would not have him in his house again. The family finances were not helped by the birth of two more children, Harriet (1819) and Frederick (1819). John Dickens did earn a small amount of money from journalism. This included an article in The Times about a big fire that had taken place in Chatham.

While living in Chatham Charles and his sister Fanny Dickens attended a school for girls and boys in Rome Lane. In 1821 he went to a school run by the twenty-three William Giles, the son of a Baptist and himself a Dissenter. His friend, John Forster, has commented: "He (Charles Dickens) was a very little and a very sickly boy. He was subject to attacks of violent spasm which disabled him for any active exertion. He was never a good little cricket-player; he was never a first-rate hand at marbles, or peg-top, or prisoner's base; but he had great pleasure in watching the other boys, officers' sons for the most part, at these games, reading while they played; and he had always the belief that this early sickness had brought to himself one inestimable advantage, in the circumstance of his weak health having strongly inclined him to reading."

Dickens was given access to his father's collection of books: "My father had left a small collection of books in a little room upstairs to which I had access (for it adjoined my own), and which nobody else in our house ever troubled. From that blessed little room, Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle, Humphrey Clinker, Tom Jones, The Vicar of Wakefield, Don Quixote, Gil Blas and Robinson Crusoe came out, a glorious host, to keep me company. They kept alive my fancy, and my hope of something beyond that place and time - they, and the Arabian Nights, and the Tales of the Genii - and did me no harm; for, whatever harm was in some of them, was not there for me."

In 1822 John Dickens returned to work at Somerset House in London and the family moved to Camden Town. Here he met and became friendly with a fellow worker, Charles Dilke. The following year, Fanny Dickens was awarded a place at the Royal Academy of Music in Hanover Square. She was to study the piano with Ignaz Moscheles, a former pupil of Ludwig van Beethoven. The fees were thirty-eight guineas a year, an expense that they family could not really afford.

Claire Tomalin has argued: "Dickens maintained that he never felt any jealousy of what was done for her, he could not help but be aware of the contrast between his position and hers, and of their parents' readiness to pay handsome fees for her education, and nothing for his. It is such a reversal of the usual family situation, where only the education of the boys is taken seriously, that the Dickens parents at least deserve some credit for making sure Fanny had a professional training, although none for their neglect of her brother." Dickens's friend, John Forster, commented: "What a stab to his heart it was, thinking of his own disregarded condition, to see her go away to begin her education, amid the tearful good wishes of everyone in the house."

Elizabeth Dickens thought that she could educate the rest of the children by starting her own school. She took a lease on a large house in Gower Street North. Charles helped his mother distribute circulars advertising the school. He later recalled: "I left, at a great many other doors, a great many circulars calling attention to the merits of the establishment. Yet nobody ever came to school, nor do I recollect that anybody ever proposed to come, or that the least preparation was made to receive anybody. But I know that we got on very badly with the butcher and baker; that very often we had not too much for dinner."

In February 1824, John Dickens was arrested for debt and sent to the Marshalsea Prison in Southwark. It has been estimated that over 30,000 people a year were arrested for debt during this period. The insolvent debtor was classed as a quasi-criminal and kept in prison until he could pay or could claim release under the Insolvent Debtors' Act.

Charles Dickens was used by his father as a messenger to carry his requests for help to family and friends. He already owed these people money and no one was willing to pay the money that would free him from captivity. He later told John Forster: "My father was waiting for me in the lodge, and we went up to his room (on the top story but one), and cried very much. And he told me, I remember, to take warning by the Marshalsea, and to observe that if a man had twenty pounds a year, and spent nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence, he would be happy; but that a shilling spent the other way would make him wretched. I see the fire we sat before now; with two bricks inside the rusted grate, one on each side, to prevent its burning too many coals."

Although only eleven years old, Charles was now considered the "man of the family" and was given the task of taking the books that he loved so much to a pawnbroker in the Hampstead Road. This was followed by items of furniture, until after a few weeks the house was almost empty. Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): "It was not so many years before that Dickens's maternal grandfather had absconded as an embezzler, and there were theories in this period concerning some inherited propensity towards crime as well as towards madness. It might have seemed to the young Dickens that this was indeed his true inheritance, which is perhaps why some critics have believed that Dickens's great contribution to the description of childhood lies in his depiction of infantile guilt."

A family friend, James Lamert, suggested to Elizabeth Dickens, that Charles should work in his uncle's blacking factory, that was based at a warehouse at 30 Hungerford Stairs. Warren's Blacking Factory, manufactured boot and shoe blacking. Lamert offered Charles the job of covering and labelling the pots of blacking. He would be paid six shillings a week and Lamert promised that he personally would give him lessons during his lunch hour to keep up his education. Charles was disappointed by his parents' reaction to the offer: "My father and mother were quite satisfied. They could hardly have been more so, if I had been twenty years of age, distinguished at a grammar-school, and going to Cambridge."

On Monday, 9th February, 1824, just two days after his twelfth birthday, he walked the three miles from Camden Town to the Warren's Blacking Factory. Charles Dickens later recalled: "The blacking warehouse was the last house on the left-hand side of the way, at old Hungerford Stairs. It was a crazy, tumbledown old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscotted rooms and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again. The counting-house was on the first floor, looking over the coal-barges and the river. There was a recess in it, in which I was to sit and work. My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking; first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper; to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat, all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary's shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label; and then go on again with more pots. Two or three other boys were kept at similar duty downstairs on similar wages. One of them came up, in a ragged apron and a paper cap, on the first Monday morning, to show me the trick of using the string and tying the knot. His name was Bob Fagin."

Charles Dickens took lodgings in Little College Street in Camden Town. Mrs Royance took in the children cheaply and treated them accordingly. He had to share a room with two other boys. On Sundays he collected Fanny Dickens from the Royal Academy of Music and they went together to the Marshalsea Prison to spend the day with their parents. He told his father how much he hated being separated from the family all week, with nothing to return to each evening. As a result he was moved to another lodging house in Lant Street that was close to the prison and he was able to spend time with his parents every evening after work. At this time Dickens believed that his father would remain incarcerated until his death.

Charles Dickens later told John Forster about this period in his life: "I know I do not exaggerate, unconsciously and unintentionally, the scantiness of my resources and the difficulties of my life. I know that if a shilling or so were given me by any one, I spent it in a dinner or a tea. I know that I worked, from morning to night, with common men and boys, a shabby child. I know that I tried, but ineffectually, not to anticipate my money, and to make it last the week through; by putting it away in a drawer I had in the counting-house, wrapped into six little parcels, each parcel containing the same amount, and labelled with a different day. I know that I have lounged about the streets, insufficiently and unsatisfactorily fed. I know that, but for the mercy of God, I might easily have been, for any care that was taken of me, a little robber or a little vagabond... I suffered in secret, and that I suffered exquisitely, no one ever knew but I. How much I suffered, it is, as I have said already, utterly beyond my power to tell. No man's imagination can overstep the reality."

On 29th June 1824, Fanny Dickens performed at a public concert at which Princess Augusta, the sister of King George IV, presented the prizes. Charles Dickens later recalled: "I could not bear to think of myself - beyond the reach of all such honourable emulation and success. The tears ran down my face. I felt as if my heart were rent. I prayed, when I went to bed that night, to be lifted out of the humiliation and neglect in which I was. I had never suffered so much before." Dickens added unconvincingly, "There was no envy in this."

In April 1825, John Dickens's mother died. He inherited the sum of £450, and he was able to pay off his debts. This allowed him to petition for release from prison, and at the end of May he was discharged from Marshalsea Prison. The Naval Pay Office agreed to take Dickens back and although he was only 39 years old, he requested to be retired early with an invalid's pension because of "a chronic infection of the urinary organs". He was eventually granted a pension of £145.16s.8d. a year.

Despite the improvement in his financial circumstances, John Dickens expected his son to continue working at Warren's Blacking Factory. The business had moved to Chandos Street in Covent Garden where he worked by a window looking out on the street and where his humiliating drudgery was exposed to public view. One day, John Dickens walked past the window with Charles Dilke. The two men stopped to watch the boys at work. Dickens told Dilke that one of the boys was his son. Claire Tomalin explains: "Dilke, a sensitive and kindly man, went in and gave him half a crown, and received in return a very low bow. This scene, described by Dilke, not Dickens, does more to suggest the humiliation he felt in being put in such a position than anything else: pitied and tipped, while his father stood simpering by."

Charles Dickens health was still poor: "Bob Fagin was very good to me on the occasion of a bad attack of my old disorder. I suffered such excruciating pain that time, that they made a temporary bed of straw in my old recess in the counting-house, and I rolled about on the floor, and Bob filled empty blacking-bottles with hot water, and applied relays of them to my side, half the day. I got better, and quite easy towards evening; but Bob (who was much bigger and older than I) did not like the idea of my going home alone, and took me under his protection. I was too proud to let him know about the prison; and after making several efforts to get rid of him, to all of which Bob Fagin in his goodness was deaf, shook hands with him on the steps of a house near Southwark Bridge on the Surrey side, making believe that I lived there."

Dickens later wrote: "No words can express the secret agony of my soul as I sunk into this companionship of common men and boys." Peter Ackroyd has argued in Dickens (1990): "Here one senses some imitation of his father's own projection of a genteel persona (it is clear enough how John Dickens's fear, stemming from the fact that he was so perilously hovering between classes, was transmitted to the son). It also tells us much about his instinctive reaction to the labouring poor, although it is one that would have been widely shared in his lifetime; the working classes were in a very real sense a race apart, a substratum of society which bred in those above them a fear of disease, a horror of uncleanliness and of course the dread of some kind of social revolution."

John Dickens and George Lamert were often in dispute: "My father and the relative so often mentioned quarrelled; quarrelled by letter, for I took the letter from my father to him which caused the explosion, but quarrelled very fiercely. It was about me. It may have had some backward reference, in part, for anything I know, to my employment at the window. All I am certain of is that, soon after I had given him the letter, my cousin (he was a sort of cousin, by marriage) told me he was very much insulted about me; and that it was impossible to keep me, after that. I cried very much, partly because it was so sudden, and partly because in his anger he was violent about my father, though gentle to me. Thomas, the old soldier, comforted me, and said he was sure it was for the best. With a relief so strange that it was like oppression, I went home."

However, Elizabeth Dickens wanted Charles to continue at the blacking factory. "My mother set herself to accommodate the quarrel, and did so next day. She brought home a request for me to return next morning, and a high character of me, which I am very sure I deserved. My father said I should go back no more, and should go to school. I do not write resentfully or angrily: for I know how all these things have worked together to make me what I am: but I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back. From that hour until this at which I write, no word of that part of my childhood which I have now gladly brought to a close, has passed my lips to any human being. I have no idea how long it lasted; whether for a year, or much more, or less. From that hour, until this, my father and my mother have been stricken dumb upon it. I have never heard the least allusion to it, however far off and remote, from either of them."

Long after his death, Mamie Dickens wrote about her father's life during this period: "His mother and the rest of the family, with the exception of his sister Fanny... lived in a poor part of London, too far away from the blacking warehouse for him to go and have his dinner with them; so he had to carry his food with him, or buy it at some cheap eating house, as he wandered about the streets, during the dinner hour. When Charles had enough money he would buy some coffee and a slice of bread and butter. When the poor little pocket was empty, he wandered about the streets again, gazing into shop windows."

Andrew Sanders, the author of Authors in Context: Charles Dickens (2003), has pointed out: "Dickens, like his parents, was to remain almost completely silent about this dark but formative period in his life. Only in the 1840s was he privately prepared to record the painful details and to show them to his wife and to his friend, John Forster. It was Forster who published most of his self-pitying autobiographical fragment after the novelist's death. For the most part, Dickens's boyhood misery was translated into fiction. The memory of his months in the blacking-factory became part of a habit of secrecy. It may also be integral to Dickens's awareness of the significance of leading a double life, a doubleness so frequently practised by his later characters."

On the insistence of his father, John Dickens was sent to Wellington House Academy on Granby Terrace adjoining Mornington Crescent. Dickens passionately disliked the man who owned the school: "The respected proprietor of which was by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know, who was one of the worst-tempered men perhaps that ever lived, whose business it was to make as much out of us and to put as little into us as possible."

Owen P. Thomas was a fellow student at the school: "My recollection of Dickens whilst at school, is that of a healthy looking boy, small but well-built, with a more than usual flow of spirits, inducing to harmless fun, seldom or ever I think to mischief, to which so many lads at that age are prone.... He usually held his head more erect than lads ordinarily do, and there was a general smartness about him. His week-day dress of jacket and trousers, I can clearly remember, was what is called pepper-and-salt; and instead of the frill that most boys of his age wore then, he had a turn-down collar, so that he looked less youthful in consequence. He invented what we termed a lingo, produced by the addition of a few letters of the same sound to every word; and it was our ambition, walking and talking thus along the street, to be considered foreigners." Another boy pointed out: "He appeared always like a gentleman's son, rather aristocratic than otherwise."

At Wellington House Academy Dickens was taught traditional subjects such as Latin. Dickens did not distinguish himself as a scholar at the school. However, he did enjoy helping to produce the school newspaper. He also wrote and performed in plays. One boy at the school observed that "he was very fond of theatricals... and used to act little plays in the kitchen." He also spent a lot of time reading a sixteen-page weekly, The Terrific Register. He later recorded that the murder stories "frightened my very wits out of my head".

Dickens left the school in February 1827, when he was fifteen years of age. Once again John Dickens was deeply in debt. Fanny's fees at the Royal Academy of Music were so badly in arrears that she had to leave; but she showed such promise and determination that she was able to make an arrangement which allowed her to return and pay for her studies by taking on part-time teaching.

Elizabeth Dickens was able to arrange for her son to work as an office boy at the Ellis & Blackmore law firm in Gray's Inn. A fellow clerk, George Lear, described Dickens during this period: "His appearance was altogether prepossessing. He was a rather short but stout-built boy, and carried himself very upright - and the idea he gave me was that he must have been drilled by a military instructor... His complexion was a healthy pink - almost glowing - rather a round face, fine forehead, beautiful expressive eyes full of animation, a firmly-set mouth, a good-sized rather straight nose... His hair was a beautiful brown, and worn long, as was then the fashion."

Dickens was popular with the other clerks. Lear claimed that "Dickens could imitate, in a manner that I have never heard equalled, the low population of the streets of London in all their varieties, whether mere loafers or sellers of fruit, vegetables, or anything else.... He could also excel in mimicking the popular singers of the day, whether comic or patriotic; as to his acting he could give us Shakespeare by the ten minutes, and imitate all the leading actors of that time." According to Dickens: "I went to some theatre every night, with a very few exceptions, for at least three years: really studying the bills first, and going to see where there was the best acting... I practised immensely (even such things as walking in and out, and sitting down in a chair)."

In November 1828 Charles Dickens went to work for another solicitor, Charles Molloy, in Chancery Lane, where he knew one of the clerks, Thomas Mitton. Dickens disliked legal work and he purchased a copy of Gurney's Brachgraphy and taught himself shorthand. Later he joined his father working for his brother-in-law, John Barrow, who had started up a newspaper, the Mirror of Parliament. Barrow's intention was to rival Hansard by offering a complete record of what went on at the House of Commons.

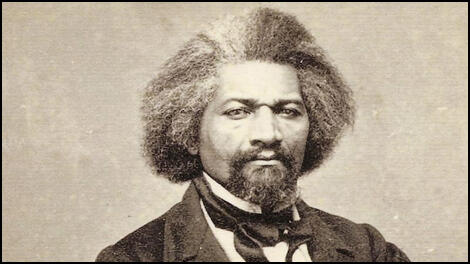

On this day in 1817 Frederick Washington Bailey, the son of a white man and a black slave, was born in Tukahoe, Maryland. He never knew his father and was separated from his mother when very young.

Douglas lived with his grandmother on a plantation until the age of eight, when he was sent to Hugh Auld in Baltimore. The wife of Auld defied state law by teaching him to read.

When Auld died in 1833 Frederick was returned to his Maryland plantation. In 1838 he escaped to New York City where he changed his name to Frederick Douglass. He later moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he worked as a labourer.

After hearing him make a speech at a meeting in 1841, William Lloyd Garrison arranged for Douglass to become an agent and lecturer for the American Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass was a great success in this work and in 1845 the society helped him publish his autobiography, the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

After the publication of his book, Douglass was afraid he might be recaptured by his former owner and so he travelled to Britain where he lectured on slavery. While in Britain he raised the funds needed to establish his own anti-slavery newspaper, the North Star. This created a break with William Lloyd Garrison, who was opposed to a separate, black-owned press.

During the Civil War Douglass, a Radical Republican, tried to persuade President Abraham Lincoln that former slaves should be allowed to join the Union Army. After the war Douglass campaigned for full civil rights for former slaves and was a strong supporter of women's suffrage.

Douglass held several public posts including assistant secretary of the Santo Domingo Commission (1871), marshall of the District of Columbia (1877-1881) and U.S. minister to Haiti (1889-1891). In 1881 he published the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Frederick Douglass died in Washington on 20th February, 1895.

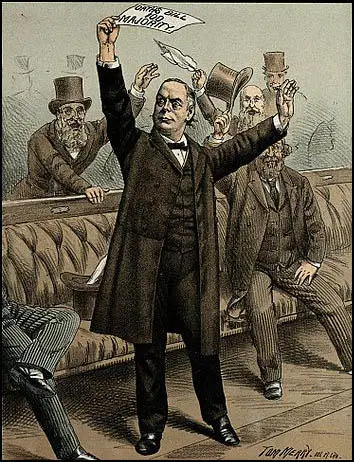

On this day in 1882 Charles Bradlaugh presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat in the House of Commons. Charles Bradlaugh was a member of the Liberal Party and in the 1880 General Election he won the seat of Northampton. At this time the law required in the courts and oath from all witnesses. Bradlaugh saw this an opportunity to draw attention to the fact that "atheists were held to be incapable of taking a meaningful oath, and were therefore treated as outlaws."

Bradlaugh argued that the 1869 Evidence Amendment Act gave him a right he asked for permission to affirm rather than take the oath of allegiance. The Speaker of the House of Commons refused this request and Bradlaugh was expelled from Parliament. William Gladstone supported Bradlaugh's right to affirm, but as he had upset a lot of people with his views on Christianity, the monarchy and birth control and when the issue was put before Parliament, MPs voted to support the Speaker's decision to expel him.

Bradlaugh now mounted a national campaign in favour of atheists being allowed to sit in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh gained some support from some Nonconformists but he was strongly opposed by the Conservative Party and the leaders of the Anglican and Catholic clergy. When Bradlaugh attempted to take his seat in Parliament in June 1880, he was arrested by the Sergeant-at-Arms and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the Conservative Party, warned that Bradlaugh would become a martyr and it was decided to release him.

On 26th April, 1881, Charles Bradlaugh was once again refused permission to affirm. William Gladstone promised to bring in legislation to enable Bradlaugh to do this, but this would take time. Bradlaugh was unwilling to wait and when he attempted to take his seat on 2nd August he was once forcibly removed from the House of Commons. Bradlaugh and his supporters organised a national petition and on 7th February, 1882, he presented a list of 241,970 signatures calling for him to be allowed to take his seat. However, when he tried to take the Parliamentary oath, he was once again removed from Parliament.

The authorities attempted to obstruct the activities of Charles Bradlaugh and other freethinkers in the National Secular Society. Pamphlets on religion were seized by the Post Office and on several occasions they were excluded from using public buildings for their meetings. In 1882 the staff of the journal, The Freethinker, were prosecuted for blasphemy, and two of them were found guilty and sent to prison.

Gladstone's Affirmation Bill was discussed by Parliament in the spring of 1883. The Archbishop of Canterbury and Cardinal Manning, head of the Catholic Church, argued against the right of atheists to be MPs and when the vote was taken in May 1883, the Affirmation Bill was defeated. In 1884 Bradlaugh was once again elected to represent Northampton in the House of Commons. He took his seat and voted three times before he was excluded. He was later fined £1,500 for voting illegally.

Charles Bradlaugh was elected once again for Northampton in the 1885 General Election. He tried again to take the oath on 13th January, 1886. The new Speaker, Sir Arthur Wellesley Peel, did not object, arguing that he had to authority to interfere with the oath-taking. Bradlaugh now had the right to speak and vote in the House of Commons. Bradlaugh now became a loyal supporter of William Gladstone, the prime minister, who had a radical agenda.

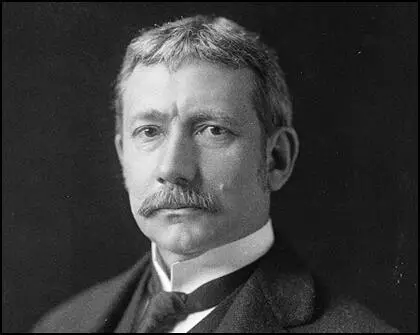

On this day in 1937 Elihu Root, died. Root was born in Clinton, New York, on 15th February, 1845. After graduating with a law degree from New York University in 1867 he became a leading corporation lawyer. He also served as U.S. attorney for the southern district of New York (1883-85). An active member of the Republican Party, Root became a legal adviser to Theodore Roosevelt.

In 1899 President William McKinley appointed Root as his secretary of war. After the assassination of McKinley, Root served under Theodore Roosevelt. He reorganized the United States Army and established a governmental system for Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

After leaving the post in 1909 Root was elected as a Republican Party senator for New York. The following year he became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912 and after the First World War was a staunch advocate of the League of Nations.